Castle of Good Hope

The Castle of Good Hope (Dutch: Kasteel de Goede Hoop; Afrikaans: Kasteel die Goeie Hoop)[1]) is a bastion fort built in the 17th century in Cape Town, South Africa. Originally located on the coastline of Table Bay, following land reclamation the fort is now located inland.[2][3] In 1936 the Castle was declared a historical monument (now a provincial heritage site) and following restorations in the 1980s it is considered the best preserved example of a Dutch East India Company fort.[4]

| Castle of Good Hope | |

|---|---|

| South Africa | |

Gateway to the Castle of Good Hope | |

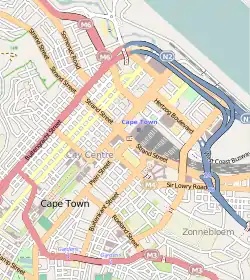

Castle of Good Hope Location in central Cape Town | |

| Coordinates | 33°55′33″S 18°25′40″E |

| Type | Bastion fort |

| Site information | |

| Controlled by | |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1666–1679 |

| Battles/wars | Second Boer War |

History

Built by the Dutch East India Company between 1666 and 1679, the Castle is the oldest existing building in South Africa.[3] It replaced an older fort called the Fort de Goede Hoop which was constructed from clay and timber and built by Jan van Riebeeck upon his arrival at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.[5] Two redoubts, Redoubt Kyckuit (Lookout) and Redoubt Duijnhoop (Duneheap) were built at the mouth of the Salt River in 1654.[6] The purpose of the Dutch settlement in the Cape was to act as a replenishment station for ships passing the treacherous coast around the Cape on long voyages between the Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia).[6]

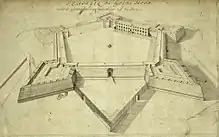

During 1664, tensions between Great Britain and the Netherlands rose amid rumours of war. That same year, Commander Zacharias Wagenaer, successor to Jan van Riebeeck, was instructed by Commissioner Isbrand Goske to build a pentagonal fortress out of stone. The first stone was laid on 2 January 1666.[6] The fortress was partially built by slave labor. The VOC was unsure about the size of the local population groups and thus feared a revolt if they enslaved them; instead they brought in up to 60,000 enslaved people from Madagascar, Mozambique, the Dutch-Indies, and India.[7] Work was interrupted frequently because the Dutch East India Company was reluctant to spend money on the project. On 26 April 1679, the five bastions were named after the main titles of William III of Orange-Nassau: Leerdam to the west, with Buuren, Katzenellenbogen, Nassau, and Oranje clockwise from it.[5] The names of these bastions have been used as street names in suburbs in various provinces, but primarily of Cape Town, such as Stellenberg, Bellville.

In 1682 the gated entry replaced the old entrance, which had faced the sea. A bell tower, situated over the main entrance, was built in 1684—the original bell, the oldest in South Africa, was cast in Amsterdam in 1697 by the East-Frisian bellmaker Claude Fremy, and weighs just over 300 kilograms (660 lb). It was used to announce the time, as well as warning citizens in case of danger, since it could be heard 10 kilometres away. It was also rung to summon residents and soldiers when important announcements needed to be made.[8]

The fortress housed a church, bakery, various workshops, living quarters, shops, and cells, among other facilities. The yellow paint on the walls was originally chosen because it lessened the effect of heat and the sun. A wall, built to protect citizens in case of an attack, divides the inner courtyard, which also houses the De Kat Balcony,[note 1] which was designed by Louis Michel Thibault with reliefs and sculptures by Anton Anreith. The original was built in 1695, but rebuilt in its current form between 1786 and 1790. From the balcony, announcements were made to soldiers, slaves and burghers of the Cape. The balcony leads to the William Fehr collection of paintings and antique furniture.[6] It was briefly home to Lady Anne Barnard, after whom one of the Castle function rooms is named.

During the Second Boer War (1899–1902), part of the castle was used as a prison, and the former cells remain to this day. Fritz Joubert Duquesne, later known as the man who killed Kitchener and the leader of the Duquesne Spy Ring, was one of its more well-known residents. The walls of the castle were extremely thick, but night after night, Duquesne dug away the cement around the stones with an iron spoon. He nearly escaped one night, but a large stone slipped and pinned him in his tunnel. The next morning, a guard found him unconscious but alive.[10]

In 1936, the Castle was declared an historical monument (from 1969 known as a national monument and since 1 April 2000 a provincial heritage site), the first site in South Africa to be so protected.[11] Extensive restorations were completed during the 1980s making the Castle the best preserved example of a Dutch East India Company fort.[4]

The Castle acted as local headquarters for the South African Army in the Western Cape, and today houses the Castle Military Museum and ceremonial facilities for the traditional Cape Regiments. The Castle is also the home of the Cape Town Highlanders Regiment, a mechanised infantry unit.[6]

Symbolism

Prior to being replaced in 2003, the distinctive shape of the pentagonal castle was used on South African Defence Force flags, formed the basis of some rank insignia of major and above, and was used on South African Air Force aircraft.

.svg.png.webp) The South African Defence Force Ensign from 1994 to 2003

The South African Defence Force Ensign from 1994 to 2003.svg.png.webp) Naval ensign of South Africa prior to 1994, showing the castle insignia

Naval ensign of South Africa prior to 1994, showing the castle insignia.svg.png.webp) Roundel of the South African Air Force from 1982 to 2003

Roundel of the South African Air Force from 1982 to 2003

Gallery

Inner view of the entrance

Inner view of the entrance The six historical flags that have flown over the Cape, in chronological order from right to left: the Prince's Flag, the flag of Great Britain, the Batavian flag, the flag of the United Kingdom, the old South African flag, and the current South African flag

The six historical flags that have flown over the Cape, in chronological order from right to left: the Prince's Flag, the flag of Great Britain, the Batavian flag, the flag of the United Kingdom, the old South African flag, and the current South African flag Pediment above entrance to castle.

Pediment above entrance to castle. Entrance of main building

Entrance of main building A cannon in the castle

A cannon in the castle A model of the castle as it would have appeared between 1710 and 1790.

A model of the castle as it would have appeared between 1710 and 1790.

See also

Notes

- "Kat" is a Dutch term for a transverse wall built for fortification purposes. It dates from Roman times when it also meant a seat of authority or place of command on a battlefield.[9]

References

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 May 2018. Retrieved 27 May 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Dirk Teeuwen (2007) Kasteel De Goede Hoop, Castle of Good Hope Archived 24 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Home". castleofgoodhope.co.za.

- "Castle of Good Hope". places.co.za.

- Peter Schirmer (1983) Cape Town, The Fairest Cape, C.Struik (Pty) Ltd., Cape Town ISBN 0-86977-186-8

- "Colonial Voyage – The website dedicated to the Colonial History". Colonial Voyage. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010.

- van Gelder, Elles (28 June 2023). "Nazaten slaafgemaakten in Zuid-Afrika willen ook Nederlandse erkenning" (in Dutch). Nederlandse Omroep Stichting. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- "Welcome to the Castle of Good Hope". Archived from the original on 11 September 2011. Retrieved 8 September 2010.

- Cape Town Highlanders "De Kat Balcony". Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2010., Dirk Teeuwen (2007) Kasteel De Goede Hoop

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1944). Taking Chances. Los Angeles, California: Haynes Corp. p. 293. ISBN 1-879356-32-5.

- p.2, Oberholster JJ, The Historical Monuments of South Africa, Cape Town: The Rembrandt van Rijn Foundation, 1972

Further reading

- Lalou Meltzer (1997). The Castle of Good Hope, Cape Town. Art Link. ISBN 0-620-20823-6.

- Ras, A.C. (1959). Die Kasteel en Ander Vroe Kaapse Vestingwerke. Tafelberg-Uitgewers

- Eric Rosenthal (1966). 300 years of the Castle at Cape Town. H.M. Joynt.