Ceratosuchops

Ceratosuchops (meaning "horned crocodile face") is a genus of spinosaurid from the Early Cretaceous (Barremian) of Britain.[1]

| Ceratosuchops Temporal range: Barremian, | |

|---|---|

| |

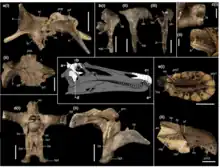

| Holotype skull fragments | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Spinosauridae |

| Clade: | †Ceratosuchopsini |

| Genus: | †Ceratosuchops Barker et al., 2021 |

| Type species | |

| †Ceratosuchops inferodios Barker et al., 2021 | |

Discovery and naming

In 2021, the type species C. inferodios was named and described by a team of paleontologists including Chris Barker, Darren Naish, David Hone and others. The specific name means "hell heron", in reference to the ecology presumed by the research team.[1]

The holotype remains of this taxon consist of IWCMS 2014.95.5 (premaxillary bodies), IWCMS 2021.30 (a posterior premaxilla fragment) and IWCMS 2014.95.1-3 (a nearly complete braincase), all of which were recovered from rocks in Chilton Chine of the Wessex Formation and stored at Dinosaur Isle museum. Referred remains include a single right postorbital (IWCMS 2014.95.4).[1]

Classification

The authors recovered Ceratosuchops as a member of the newly erected clade, Ceratosuchopsini, closely related to Suchomimus and the coeval Riparovenator.[1][2]

| Baryonychinae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Palaeobiology

A 2023 study by Barker and colleagues based on CT scans of the braincases of Ceratosuchops and Baryonyx found that the brain anatomy of these baryonychines was similar to that of other non-maniraptoriform theropods. Their neurosensory capabilities such as hearing and olfaction (sense of smell) were unexceptional, and their gaze stabilisation less developed than those of spinosaurines, so their behavioural adaptations were probably comparable to those of other large-bodied terrestrial theropods. This suggests that their transition from terrestrial hypercarnivores to semi-aquatic “generalists” during their evolution did not require substantial modification of their brain and sensory systems. This could mean that spinosaurids were either pre-adapted for detection and capture of aquatic prey, or that their transition to semi-aquatic lifestyles only required modifications to the bones associated with the mouth. Their reptile encephalization quotient values imply that the cognitive capacity and behavioural sophistication of baryonychines did not deviate much from that of other basal theropods.[3]

Palaeoenvironment

Ceratosuchops lived in a dry mediterranean habitat in the Wessex Formation, where rivers were home to riparian zones.[4][5] Like most spinosaurs, it would have fed on available small to medium-sized aquatic and terrestrial prey in these areas.[6][7][8]

Other dinosaurs from the Wessex Formation of the Isle of Wight include the theropods Riparovenator, Neovenator, Eotyrannus, Aristosuchus, Thecocoelurus, Calamospondylus, and Ornithodesmus; the ornithopods Iguanodon, Hypsilophodon, and Valdosaurus; the sauropods Ornithopsis, Eucamerotus, and Chondrosteosaurus; and the ankylosaur Polacanthus.[9][1] Barker and colleagues stated in 2021 that the identification of the two additional spinosaurids from the Wealden Supergroup, Riparovenator and Ceratosuchops, has implications for potential ecological separation within Spinosauridae if these and Baryonyx were contemporary and interacted. They cautioned that it is possible the Upper Weald Clay and Wessex Formations and the spinosaurids known from them were separated in time and distance.[1]

It is generally thought that large predators occur with small taxonomic diversity in any area due to ecological demands, yet many Mesozoic assemblages include two or more sympatric theropods that were comparable in size and morphology, and this also appears to have been the case for spinosaurids. Barker and colleagues suggested that high diversity within Spinosauridae in a given area may have been the result of environmental circumstances benefiting their niche. While it has been generally assumed that only identifiable anatomical traits related to resource partitioning allowed for coexistence of large theropods, Barker and colleagues noted that this does not preclude that similar and closely related taxa could coexist and overlap in ecological requirements. Possible niche partitioning could be in time (seasonal or daily), in space (between habitats in the same ecosystems), or depending on conditions, and they could also have been separated by their choice of habitat within their regions (which may have ranged in climate).[1]

References

- Barker, C.T.; Hone, D.; Naish, D.; Cau, A.; Lockwood, J.; Foster, B.; Clarkin, C.; Schneider, P.; Gostling, N. (2021). "New spinosaurids from the Wessex Formation (Early Cretaceous, UK) and the European origins of Spinosauridae". Scientific Reports. 11 (1): 19340. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-97870-8. PMC 8481559. PMID 34588472.

- Naish, Darren (September 29, 2021). "Two New Spinosaurid Dinosaurs from the English Cretaceous". Tetrapod Zoology. Archived from the original on 2021-09-29.

- Barker, Chris Tijani; Naish, Darren; Trend, Jacob; Michels, Lysanne Veerle; Witmer, Lawrence; Ridgley, Ryan; Rankin, Katy; Clarkin, Claire E.; Schneider, Philipp; Gostling, Neil J. (2023). "Modified skulls but conservative brains? The palaeoneurology and endocranial anatomy of baryonychine dinosaurs (Theropoda: Spinosauridae)". Journal of Anatomy: joa.13837. doi:10.1111/joa.13837. PMC 10184548.

- Penn, Simon J.; Sweetman, Steven C.; Martill, David M.; Coram, Robert A. (2020). "The Wessex Formation (Wealden Group, Lower Cretaceous) of Swanage Bay, southern England" (PDF). Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 131 (6): 679–698. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2020.07.005. S2CID 228820795.

- Radley, Jonathan D.; Allen, Percival (2012). "The southern English Wealden (Non-marine Lower Cretaceous): Overview of palaeoenvironments and palaeoecology". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 123 (2): 382–385. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2011.12.005.

- Hendrickx, C.; Mateus, O.; Buffetaut, E. (2016). "Morphofunctional Analysis of the Quadrate of Spinosauridae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and the Presence of Spinosaurus and a Second Spinosaurine Taxon in the Cenomanian of North Africa". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0144695. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1144695H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144695. PMC 4703214. PMID 26734729.

- "'Hell heron' dinosaur is new species found on Isle of Wight".

- "'Horned crocodile-faced hell heron' is one of two new Isle of Wight dinosaur discoveries". 29 September 2021.

- Martill, D. M.; Hutt, S. (1996). "Possible baryonychid dinosaur teeth from the Wessex Formation (Lower Cretaceous, Barremian) of the Isle of Wight, England". Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 107 (2): 81–84. doi:10.1016/S0016-7878(96)80001-0.

.jpg.webp)