Chiatura

Chiatura (Georgian: ჭიათურა) is a city in the Imereti region of Western Georgia. In 1989, it had a population of about 30,000. The city is known for its system of cable cars connecting the city's center to the mining settlements on the surrounding hills. The city is located inland, in a mountain valley on the banks of the Qvirila River.

Chiatura

ჭიათურა | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) The town of Chiatura. | |

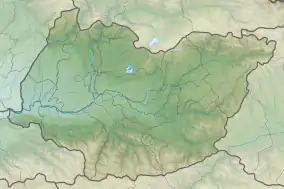

Chiatura Location of Chiatura in Georgia  Chiatura Chiatura (Imereti) | |

| Coordinates: 42°17′25″N 43°16′55″E | |

| Country | |

| Mkhare | Imereti |

| District | Chiatura |

| Population (January 1, 2023)[1] | |

| • Total | 12,280 |

| Time zone | UTC+4 (Georgian Time) |

| Climate | Cfb |

Geography and history

.jpg.webp)

In 1879 the Georgian poet Akaki Tsereteli explored the area in search of manganese and iron ores, discovering deposits in the area. After other intense explorations it was discovered that there are several layers of commercially exploitable manganese oxide, peroxide and carbonate with thickness varying between 0.2 m (0.66 ft) and 16 m (52 ft). The state set up the JSC Chiaturmanganese company to manage and exploit the huge deposit. The gross-balance of workable manganese ores of all commercial categories is estimated as 239 million tonnes, which include manganese oxide ores (41.6%), carbonate ores (39%), and peroxide ores (19%).[2][3][4] In order to transport manganese ore to the ferro-alloy plant in Zestaphoni the company developed a rail link which, operated today by Georgian Railways, is fully electrified. Manganese production rose to 60% of global output by 1905.

In Chiatura are located the Tsereteli State Theater, 10 schools, Faculty of the Georgian Technical University, and the Mgvimevi Cathedral (10th-11th centuries). During the 1905 Russian Revolution Chiatura was the only Bolshevik stronghold in mostly Menshevik Georgia. 3,700 miners worked 18 hours a day sleeping in the mines, always covered in soot. They didn't even have baths. Joseph Stalin persuaded them to back Bolshevism during a debate with the Mensheviks. They preferred his simple 15-minute speech to his rivals' oratory. They called him "sergeant major Koba". He set up a printing press, protection racket and "red battle squads". Stalin put Vano Kiasashvili in charge of the armed miners. The mine owners actually sheltered him as he would protect them from thieves in return and he destroyed mines whose owners refused to pay up.[5]

In 1906, a gold train carrying the miners' wages was attacked by Kote Tsintsadze's Druzhina (Bolshevik Expropriators' Club). They fought for two hours, killing a gendarme and a soldier and stealing 21,000 roubles.[6] The miners went on a successful 55-day strike in June–July 1913. They demanded an 8-hour day, higher wages and no more night work. The police allowed the RSDRP to lead the strike provided that they did not make any political demands.[7] They were supported by fellow strikers in Batumi and Poti.[8]

In 2017, City of the Sun, a documentary film directed by Rati Oneli, follows a number of citizens of the city.[9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

Cablecars

Due to the steep sided river valley, production workers spent a large amount of time walking up from the town to the mines, thereby reducing productivity. In 1954 an extensive cable car system was installed to transport workers around the valley and up to the mines. The system's 17 lines continued to serve the city using original hardware until 2021.[17][18]

In 2017, the Georgian government began rebuilding the system using modern cable car technology, beginning with the central four-line hub station.[19] The revamped system opened in September 2021. The original Soviet-era system was deemed unsafe and taken out of service.[18] The government plans to preserve its stations as heritage sites.[20]

Twin towns – sister cities

See also

References

- "Population - National Statistics Office of Georgia". www.geostat.ge.

- "Manganese Mines and Deposits of Georgia". IFSD Europe. Archived from the original on 1 October 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- The mineral industry of Georgia, ed. (2007). USGS Minerals Yearbook (PDF). National Research Council (U.S.). p. 334. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- "Manganese Ore Industry". thefreedictionary.com. 1979. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- Simon Sebag Montefiore, Young Stalin, pp 131-3

- Simon Sebag Montefiore, Young Stalin, page 130

- Ronald Grigor Suny, The making of the Georgian nation, page 178

- About us Archived July 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Previously on at the ICA: City of the Sun

- "City of the Sun (2017) - Rati Oneli". International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam. Oberon Amsterdam. 2017-10-09. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (2017-10-09). "Trailer: City of the Sun". YouTube. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "City of the Sun". Agosto Foundation. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "City of the Sun (Mzis qalaqi)". Cineuropa. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "Rati Oneli on City of the Sun". East European Film Bulletin. 6 January 2018. ISSN 1775-3635. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "City Of The Sun". Life Through Cinema. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- "RIDM 2017: City of the Sun (Georgia, 2017)". Cinetalk.net. 14 November 2017.

- "Chiatura Cable Cars and Katskhi Pillar - Stairway to Heaven - Georgian Tour Magazine". Georgian Tour Magazine. 2015-03-17. Retrieved 2016-05-10.

- "Renovated Soviet-era ropeway opens in Chiatura". Agenda.ge. Retrieved 2021-12-16.

- "Rehabilitation of ropeway roads started in Chiatura". Liberal (in Georgian). 19 January 2017. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- "Georgia's Soviet-era cable cars are finally getting an upgrade". Emerging Europe. 2021-11-13. Retrieved 2021-12-16.

- "დამეგობრებული ქალაქები". chiatura.gov.ge (in Georgian). Chiatura. Retrieved 2020-02-13.