Conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values.[1][2][3] The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in which it appears. In Western culture, depending on the particular nation, conservatives seek to promote a range of social institutions such as the nuclear family, organized religion, the military, property rights, and monarchy. Conservatives tend to favour institutions and practices that guarantee social order and that evolved gradually.[3]

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

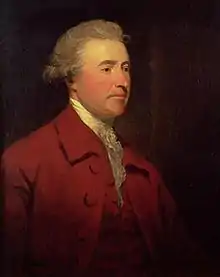

Edmund Burke, an 18th-century politician who opposed the French Revolution but supported the American Revolution, is credited as one of the main theorists of conservatism in the 1790s.[4] The first established use of the term in a political context originated in 1818 with François-René de Chateaubriand during the period of Bourbon Restoration that sought to roll back the policies of the French Revolution.[5]

Conservative thought has varied considerably as it has adapted itself to existing traditions and national cultures.[6] Thus, conservatives from different parts of the world—each upholding their respective traditions—may disagree on a wide range of issues. Historically associated with right-wing politics, the term has been used to describe a wide range of views. Conservatism may be either more libertarian or more authoritarian; more populist or more elitist; more progressive or more reactionary; more moderate or more extreme.[7]

Themes

Some political scientists such as Samuel P. Huntington have seen conservatism as situational. Under this definition, conservatives are seen as defending the established institutions of their time.[8] According to Quintin Hogg, the chairman of the British Conservative Party in 1959: "Conservatism is not so much a philosophy as an attitude, a constant force, performing a timeless function in the development of a free society, and corresponding to a deep and permanent requirement of human nature itself".[9] Conservatism is often used as a generic term to describe a "right-wing viewpoint occupying the political spectrum between liberalism and fascism."[2]

Tradition

Despite the lack of a universal definition, certain themes can be recognised as common across conservative thought. According to Michael Oakeshott:

To be conservative ... is to prefer the familiar to the unknown, to prefer the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant, the sufficient to the superabundant, the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.[10]

Such traditionalism may be a reflection of trust in time-tested methods of social organisation, giving 'votes to the dead'.[11] Traditions may also be steeped in a sense of identity.[11]

Hierarchy

In contrast to the tradition-based definition of conservatism, some left-wing political theorists such as Corey Robin define conservatism primarily in terms of a general defense of social and economic inequality.[12] From this perspective, conservatism is less an attempt to uphold old institutions and more "a meditation on—and theoretical rendition of—the felt experience of having power, seeing it threatened, and trying to win it back".[13] On another occasion, Robin argues for a more complex relation:

Conservatism is a defense of established hierarchies, but it is also fearful of those established hierarchies. It sees in their assuredness of power the source of corruption, decadence and decline. Ruling regimes require some kind of irritant, a grain of sand in the oyster, to reactivate their latent powers, to exercise their atrophied muscles, to make their pearls.[14]

Political philosopher Yoram Hazony argues that, in a traditional conservative community, members have importance and influence to the degree they are honoured within the social hierarchy, which includes factors such as age, experience, and wisdom.[15] The word hierarchy has religious roots and translates to 'rule of a high priest.'[16]

Realism

Conservatism has been called a "philosophy of human imperfection" by Noël O'Sullivan, reflecting among its adherents a negative view of human nature and pessimism of the potential to improve it through 'utopian' schemes.[17] The "intellectual godfather of the realist right", Thomas Hobbes, argued that the state of nature for humans was "poor, nasty, brutish, and short", requiring centralised authority.[18][19]

Authority

Authority is a core tenet of conservatism.[20][21] More specifically, traditional authority, according to Max Weber, is "resting on an established belief in the sanctity of immemorial traditions and the legitimacy of those exercising authority under them"—for example parents, priests, and monarchs.[22][23] Danny Kruger defines conservative authority as "the non-coercive social persuasion which operates in a family or a community".[24]

Reactionism

Reactionism is a tradition in right-wing politics that opposes policies for the social transformation of society.[25] In popular usage, reactionary refers to a strong traditionalist conservative political perspective of a person opposed to social, political, and economic change.[26][27] Adherents of conservatism often oppose certain aspects of modernity (for example mass culture and secularism) and seek a return to traditional values, though different groups of conservatives may choose different traditional values to preserve.[3][28]

Some scholars, such as Corey Robin, treat the words reactionary and conservative as synonyms.[29] Others, such as Mark Lilla, argue that reactionism and conservatism are distinct worldviews.[30] Political scientist Francis Wilson defines conservatism as "a philosophy of social evolution, in which certain lasting values are defended within the framework of the tension of political conflict".[31]

A reactionary is a person who holds political views that favor a return to the status quo ante, the previous political state of society, which that person believes possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary society. An early example of a powerful reactionary movement was German Romanticism, which centered around concepts of organicism, medievalism, and traditionalism against the forces of rationalism, secularism, and individualism that were unleashed in the French Revolution.[32][33]

In political discourse, being a reactionary is generally regarded as negative; Peter King observed that it is "an unsought-for label, used as a torment rather than a badge of honor."[34] Despite this, the descriptor has been adopted by writers such as the Austrian monarchist Erik von Kuehnelt-Leddihn,[35] the Colombian political theologian Nicolás Gómez Dávila, and the American historian John Lukacs.[36]

Intellectual history

Edmund Burke (1729–1797) has been widely regarded as the philosophical founder of modern conservatism as we know it today.[37][38] Burke served as the private secretary to the Marquis of Rockingham and as official pamphleteer to the Rockingham branch of the Whig party.[39] Together with the Tories, they were the conservatives in the late 18th century United Kingdom.[40] Burke's views were a mixture of conservatism and republicanism. He supported the American Revolution of 1775–1783 but abhorred the violence of the French Revolution (1789–1799). He accepted the conservative ideals of private property and the economics of Adam Smith (1723–1790), but thought that economics should remain subordinate to the conservative social ethic, that capitalism should be subordinate to the medieval social tradition and that the business class should be subordinate to aristocracy. He insisted on standards of honour derived from the medieval aristocratic tradition and saw the aristocracy as the nation's natural leaders.[41] That meant limits on the powers of the Crown, since he found the institutions of Parliament to be better informed than commissions appointed by the executive. He favored an established church, but allowed for a degree of religious toleration.[42] Burke ultimately justified the social order on the basis of tradition: tradition represented the wisdom of the species, and he valued community and social harmony over social reforms.[43]

.jpg.webp)

Another form of conservatism developed in France in parallel to conservatism in Britain. It was influenced by Counter-Enlightenment works by men such as Joseph de Maistre (1753–1821) and Louis de Bonald (1754–1840). Many continental conservatives do not support separation of church and state, with most supporting state recognition of and cooperation with the Catholic Church, such as had existed in France before the Revolution. Conservatives were also early to embrace nationalism, which was previously associated with liberalism and the Revolution in France.[44] Another early French conservative, François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), espoused a romantic opposition to modernity, contrasting its emptiness with the 'full heart' of traditional faith and loyalty.[45] Elsewhere on the continent, German thinkers Justus Möser (1720–1794) and Friedrich von Gentz (1764–1832) criticized the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen that came of the Revolution.[46] Opposition was also expressed by Adam Müller (1779–1829) and Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1771–1830), the latter inspiring both left and right-wing followers.[47]

Both Burke and Maistre were critical and skeptical of democracy in general, though their reasons differed.[48] Maistre was pessimistic about humans being able to follow rules, while Burke was skeptical about humans' innate ability to make rules.[49] For Maistre, rules had a divine origin, while Burke believed they arose from custom.[50] The lack of custom for Burke, and the lack of divine guidance for Maistre, meant that people would act in terrible ways.[51] Both also believed that liberty of the wrong kind led to bewilderment and political breakdown.[52] Their ideas would together flow into a stream of anti-rationalist, romantic conservatism, but would still stay separate.[53] Whereas Burke was more open to argumentation and disagreement, Maistre wanted faith and authority, leading to a more illiberal strain of thought.[54]

Ideological variants

Liberal conservatism

Liberal conservatism incorporates the classical liberal view of minimal government intervention in the economy. Individuals should be free to participate in the market and generate wealth without government interference.[55] However, individuals cannot be thoroughly depended on to act responsibly in other spheres of life; therefore, liberal conservatives believe that a strong state is necessary to ensure law and order and social institutions are needed to nurture a sense of duty and responsibility to the nation.[55] Liberal conservatism is a variant of conservatism that is strongly influenced by liberal stances.[56]

As these latter two terms have had different meanings over time and across countries, liberal conservatism also has a wide variety of meanings. Historically, the term often referred to the combination of economic liberalism, which champions laissez-faire markets, with the classical conservatism concern for established tradition, respect for authority and religious values. It contrasted itself with classical liberalism, which supported freedom for the individual in both the economic and social spheres.

Over time, the general conservative ideology in many countries adopted fiscally conservative arguments and the term liberal conservatism was replaced with conservatism. This is also the case in countries where liberal economic ideas have been the tradition such as the United States and are thus considered conservative. In other countries where liberal conservative movements have entered the political mainstream, such as Italy and Spain, the terms liberal and conservative may be synonymous. The liberal conservative tradition in the United States combines the economic individualism of the classical liberals with a Burkean form of conservatism (which has also become part of the American conservative tradition, such as in the writings of Russell Kirk).

A secondary meaning for the term liberal conservatism that has developed in Europe is a combination of more modern conservative (less traditionalist) views with those of social liberalism. This has developed as an opposition to the more collectivist views of socialism. Often this involves stressing conservative views of free market economics and belief in individual responsibility, with communitarian views on defence of civil rights, environmentalism and support for a limited welfare state. In continental Europe, this is sometimes also translated into English as social conservatism.

Libertarian conservatism

Libertarian conservatism describes certain political ideologies most prominently within the United States which combine libertarian economic issues with aspects of conservatism. Its four main branches are constitutionalism, paleolibertarianism, small government conservatism and Christian libertarianism. They generally differ from paleoconservatives, in that they favor more personal and economic freedom. Agorists such as Samuel Edward Konkin III labeled libertarian conservatism right-libertarianism.[57][58]

In contrast to paleoconservatives, libertarian conservatives support strict laissez-faire policies such as free trade, opposition to any national bank and opposition to business regulations. They are often opposed to environmental regulations, corporate welfare, subsidies and other areas of economic intervention. Many conservatives, especially in the United States, believe that the government should not play a major role in regulating business and managing the economy. They typically oppose efforts to charge high tax rates and to redistribute income to assist the poor. Such efforts, they argue, only serve to exacerbate the scourge of unemployment and poverty by lessening the ability for businesses to hire employees due to higher tax impositions.

Fiscal conservatism

Fiscal conservatism is the economic philosophy of prudence in government spending and debt.[59] In his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790), Edmund Burke argued that a government does not have the right to run up large debts and then throw the burden on the taxpayer:

[I]t is to the property of the citizen, and not to the demands of the creditor of the state, that the first and original faith of civil society is pledged. The claim of the citizen is prior in time, paramount in title, superior in equity. The fortunes of individuals, whether possessed by acquisition or by descent or in virtue of a participation in the goods of some community, were no part of the creditor's security, expressed or implied...[T]he public, whether represented by a monarch or by a senate, can pledge nothing but the public estate; and it can have no public estate except in what it derives from a just and proportioned imposition upon the citizens at large.

National conservatism

National conservatism is a political term used primarily in Europe to describe a variant of conservatism which concentrates more on national interests than standard conservatism as well as upholding cultural and ethnic identity,[60] while not being outspokenly nationalist or supporting a far-right approach.[61][62] In Europe, national conservatives are usually eurosceptics.[63][64]

National conservatism is heavily oriented towards the traditional family and social stability as well as in favour of limiting immigration. As such, national conservatives can be distinguished from economic conservatives, for whom free market economic policies, deregulation and fiscal conservatism are the main priorities. Some commentators have identified a growing gap between national and economic conservatism: "[M]ost parties of the Right [today] are run by economic conservatives who, in varying degrees, have marginalized social, cultural, and national conservatives."[65]

Traditionalist conservatism

Traditionalist conservatism is a political philosophy emphasizing the need for the principles of natural law and transcendent moral order, tradition, hierarchy and organic unity, agrarianism, classicism and high culture as well as the intersecting spheres of loyalty.[66] Some traditionalists have embraced the labels "reactionary" and "counterrevolutionary," defying the stigma that has attached to these terms since the Enlightenment. Having a hierarchical view of society, many traditionalist conservatives, including a few Americans (notable examples including Ralph Adams Cram,[67] Solange Hertz,[68] William S. Lind,[69] & Charles A. Coulombe[70]), defend the monarchical political structure as the most natural and beneficial social arrangement.

Cultural conservatism

Cultural conservatives support the preservation of the heritage of one nation, or of a shared culture that is not defined by national boundaries.[71] The shared culture may be as divergent as Western culture or Chinese culture. In the United States, the term "cultural conservative" may imply a conservative position in the culture war. Cultural conservatives hold fast to traditional ways of thinking even in the face of monumental change. They believe strongly in traditional values and traditional politics and often have an urgent sense of nationalism.

Social conservatism

Social conservatism is distinct from cultural conservatism, although there are some overlaps. Social conservatives may believe that society is built upon a fragile network of relationships which need to be upheld through duty, traditional values and established institutions;[72] and that the government has a role in encouraging or enforcing traditional values or behaviours. A social conservative wants to preserve traditional morality and social mores, often by opposing what they consider radical policies or social engineering. Social change is generally regarded as suspect.

Social conservatives today generally favour the anti-abortion position in the abortion controversy and oppose human embryonic stem cell research (particularly if publicly funded); oppose both eugenics and human enhancement (transhumanism) while supporting bioconservatism;[73] support a traditional definition of marriage as being one man and one woman; view the nuclear family model as society's foundational unit; oppose expansion of civil marriage and child adoption to couples in same-sex relationships; promote public morality and traditional family values; oppose atheism, especially militant atheism, and secularism;[74][75][76] support the prohibition of drugs, prostitution and euthanasia; and support the censorship of pornography and what they consider to be obscenity or indecency.

Religious conservatism

Religious conservatism principally applies the teachings of particular religions to politics: sometimes by merely proclaiming the value of those teachings; at other times, by having those teachings influence laws.[77]

In most democracies, political conservatism seeks to uphold traditional family structures and social values. Religious conservatives typically oppose abortion, LGBT behavior (or, in certain cases, identity), drug use,[78] and sexual activity outside of marriage. In some cases, conservative values are grounded in religious beliefs, and conservatives seek to increase the role of religion in public life.[79]

Paternalistic conservatism

Paternalistic conservatism is a strand in conservatism which reflects the belief that societies exist and develop organically and that members within them have obligations towards each other.[80] There is particular emphasis on the paternalistic obligation of those who are privileged and wealthy to the poorer parts of society. Since it is consistent with principles such as organicism, hierarchy and duty, it can be seen as an outgrowth of traditional conservatism. Paternal conservatives support neither the individual nor the state in principle, but are instead prepared to support either or recommend a balance between the two depending on what is most practical.[81] Paternalistic conservatives historically favor a more aristocratic view (as opposed to the more monarchist traditionalist conservatism) and are ideologically related to High Tories.

In more contemporary times, its proponents stress the importance of a social safety net to deal with poverty, support for limited redistribution of wealth along with government regulation of markets in the interests of both consumers and producers.[82] Paternalistic conservatism first arose as a distinct ideology in the United Kingdom under Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli's "One Nation" Toryism.[82][83] There have been a variety of one nation conservative governments. In the United Kingdom, the Prime Ministers Disraeli, Stanley Baldwin, Neville Chamberlain, Winston Churchill, and Harold Macmillan[84] were or are one nation conservatives.

In Germany, during the 19th-century German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck adopted policies of state-organized compulsory insurance for workers against sickness, accident, incapacity and old age. Chancellor Leo von Caprivi promoted a conservative agenda called the "New Course".[85]

Progressive conservatism

In the United States, Theodore Roosevelt has been the main figure identified with progressive conservatism as a political tradition. Roosevelt stated that he had "always believed that wise progressivism and wise conservatism go hand in hand".[86] The Republican administration of President William Howard Taft was a progressive conservative and he described himself as "a believer in progressive conservatism"[86] and President Dwight D. Eisenhower declared himself an advocate of "progressive conservatism."[87]

In Canada, a variety of conservative governments have been part of the Red Tory tradition, with Canada's former major conservative party being named the Progressive Conservative Party of Canada from 1942 to 2003.[88] In Canada, the Prime Ministers Arthur Meighen, R. B. Bennett, John Diefenbaker, Joe Clark, Brian Mulroney, and Kim Campbell led Red tory federal governments.[88]

Authoritarian conservatism

Authoritarian conservatism or reactionary conservatism[89][90][91] refers to autocratic regimes that center their ideology around national conservatism, rather than ethnic nationalism, though certain racial components such as antisemitism may exist.[92] Authoritarian conservative movements show strong devotion towards religion, tradition and culture while also expressing fervent nationalism akin to other far-right nationalist movements. Examples of authoritarian conservative statesmen include Miklós Horthy in Hungary, Ioannis Metaxas in Greece, António de Oliveira Salazar in Portugal,[93] Engelbert Dollfuss in Austria, and Francisco Franco in Spain.[94]

Authoritarian conservative movements were prominent in the same era as fascism, with which it sometimes clashed. Although both ideologies shared core values such as nationalism and had common enemies such as communism and materialism, there was nonetheless a contrast between the traditionalist nature of authoritarian conservatism and the revolutionary, palingenetic and populist nature of fascism—thus it was common for authoritarian conservative regimes to suppress rising fascist and Nazi movements.[95] The hostility between the two ideologies is highlighted by the struggle for power in Austria, which was marked by the assassination of ultra-Catholic statesman Engelbert Dollfuss by Austrian Nazis.

Sociologist Seymour Martin Lipset has examined the class basis of right-wing extremist politics in the 1920–1960 era. He reports:

Conservative or rightist extremist movements have arisen at different periods in modern history, ranging from the Horthyites in Hungary, the Christian Social Party of Dollfuss in Austria, Der Stahlhelm and other nationalists in pre-Hitler Germany, and Salazar in Portugal, to the pre-1966 Gaullist movements and the monarchists in contemporary France and Italy. The right extremists are conservative, not revolutionary. They seek to change political institutions in order to preserve or restore cultural and economic ones, while extremists of the centre and left seek to use political means for cultural and social revolution. The ideal of the right extremist is not a totalitarian ruler, but a monarch, or a traditionalist who acts like one. Many such movements in Spain, Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Italy have been explicitly monarchist... The supporters of these movements differ from those of the centrists, tending to be wealthier, and more religious, which is more important in terms of a potential for mass support.[96]

National variants

Conservative political parties vary widely from country to country in the goals they wish to achieve. Both conservative and liberal parties tend to favor private ownership of property, in opposition to communist, socialist and green parties, which favor communal ownership or laws requiring social responsibility on the part of property owners. Where conservatives and social liberals differ is primarily on social issues. Conservatives tend to reject behavior that does not conform to some social norm. Modern conservative parties often define themselves by their opposition to liberal or labor parties. The United States usage of the term "conservative" is unique to that country.[97]

India

In India, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), led by Narendra Modi, represent conservative politics. The BJP is the largest right-wing conservative party in the world. It promotes cultural nationalism, Hindu Nationalism, an aggressive foreign policy against Pakistan and a conservative social and fiscal policy.[98]

Singapore

Singapore's only conservative party is the People's Action Party (PAP). It is currently in government and has been in government since independence in 1965. It has promoted conservative values in the form of Asian democracy and values or 'shared values'. The main party on the left of the political spectrum in Singapore is the Workers' Party (WP).[99]

South Korea

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in South Korea |

|---|

|

South Korea's major conservative party, the People Power Party (South Korea), has changed its form throughout its history. First it was the Democratic-Liberal Party(민주자유당, Minju Ja-yudang) and its first head was Roh Tae-woo who was the first President of the Sixth Republic of South Korea. Democratic-Liberal Party was founded by the merging of Roh Tae-woo's Democratic Justice Party, Kim Young Sam's Reunification Democratic Party and Kim Jong-pil's New Democratic Republican Party. And again through election its second leader, Kim Young-sam, became the fourteenth President of Korea. When the conservative party was beaten by the opposition party in the general election, it changed its form again to follow the party members' demand for reforms. It became the New Korean Party, but it changed again one year later since the President Kim Young-sam was blamed by the citizen for the International Monetary Fund. It changed its name to Grand National Party (GNP). Since the late Kim Dae-jung assumed the presidency in 1998, GNP had been the opposition party until Lee Myung-bak won the presidential election of 2007.

Europe

European conservatism has taken many different expressions. In Italy, which was united by liberals and radicals (Risorgimento), liberals, not conservatives, emerged as the party of the right.[100] In the Netherlands, conservatives merged into a new Christian democratic party in 1980.[101] In Austria, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Portugal and Spain, conservatism was transformed into para-fascism or the far-right.[102]

Belgium

Having its roots in the conservative Catholic Party, the Christian People's Party retained a conservative edge through the twentieth century, supporting the king in the Royal Question, supporting nuclear family as the cornerstone of society, defending Christian education, and opposing euthanasia. The Christian People's Party dominated politics in post-war Belgium. In 1999, the party's support collapsed, and it became the country's fifth-largest party.[103][104][105] Currently, the N-VA (nieuw-vlaamse alliantie/New Flemish Alliance) is the largest party in Belgium.[106]

Denmark

Danish conservatism emerged with the political grouping Højre (literally "Right"), which due to its alliance with king Christian IX of Denmark dominated Danish politics and formed all governments from 1865 to 1901. When a constitutional reform in 1915 stripped the landed gentry of political power, Højre was succeeded by the Conservative People's Party of Denmark, which has since then been the main Danish conservative party.[107] Another Danish conservative party was the Free Conservatives who were active between 1902 and 1920. The Conservative People's Party led the government coalition from 1982 to 1993. The party had previously been member of various governments from 1916 to 1917, 1940 to 1945, 1950 to 1953 and 1968 to 1971. The party was a junior partner in governments led by the Liberals from 2001 to 2011[108] and again from 2016 to 2019. The party is preceded by 11 years by the Young Conservatives (KU), today the youth movement of the party.

The Conservative People's Party had a stable electoral support close to 15 to 20% at almost all general elections from 1918 to 1971. In the 1970s it declined to around 5%, but then under the leadership of Poul Schlüter reached its highest popularity level ever in 1984, receiving almost every fourth vote. Since the late 1990s the party has obtained around 5 to 10% of the vote. In the 2022 Danish general election, the party received 5.5% of the vote.[109]

Conservative thinking has also influenced other Danish political parties. In 1995 the Danish People's Party was founded, based on a mixture of conservative, national and social democratic ideas.[107] In 2015 the party New Right was established, professing a national conservative attitude.[110] In the 2022 Danish general election, the two parties received 2.6 and 3.7% of the vote, respectively.

The conservative parties in Denmark have always considered the monarchy as a central institution in Denmark.[111][112][113][114]

Finland

The conservative party in Finland is the National Coalition Party (in Finnish Kansallinen Kokoomus, Kok). The party was founded in 1918, when several monarchist parties united. Although in the past the party was right-wing, today it is a moderate liberal conservative party. While the party advocates economic liberalism, it is committed to the social market economy.[115]

France

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in France |

|---|

|

Conservatism in France focused on the rejection of the secularism of the French Revolution, support for the role of the Catholic Church and the restoration of the monarchy.[116] The monarchist cause was on the verge of victory in the 1870s, but then collapsed because the proposed king, Henri, Count of Chambord, refused to fly the tri-colored flag.[117] Religious tensions heightened in the 1890–1910 era, but moderated after the spirit of unity in fighting the First World War.[118] An extreme form of conservatism characterized the Vichy regime of 1940–1944 with heightened antisemitism, opposition to individualism, emphasis on family life and national direction of the economy.[119]

Following the Second World War, conservatives in France supported Gaullist groups and have been nationalistic and emphasized tradition, order and the regeneration of France.[120] Gaullists held divergent views on social issues. The number of conservative groups, their lack of stability and their tendency to be identified with local issues defy simple categorization. Conservatism has been the major political force in France since the Second World War.[121] Unusually, post-war French conservatism was formed around the personality of a leader, Charles de Gaulle; and did not draw on traditional French conservatism, but on the Bonapartism tradition.[122] Gaullism in France continues under The Republicans (formerly Union for a Popular Movement), which was previously led by Nicolas Sarkozy, a conservative figure in France (see Sinistrisme).[123] The word "conservative" itself is a term of abuse to many people in France.[124]

Germany

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Germany |

|---|

|

Conservatism developed alongside nationalism in Germany, culminating in Germany's victory over France in the Franco-Prussian War, the creation of the unified German Empire in 1871 and the simultaneous rise of Otto von Bismarck on the European political stage. Bismarck's "balance of power" model maintained peace in Europe for decades at the end of the 19th century. His "revolutionary conservatism" was a conservative state-building strategy designed to make ordinary Germans—not just the Junker elite—more loyal to state and emperor, he created the modern welfare state in Germany in the 1880s. According to Kees van Kersbergen and Barbara Vis, his strategy was:

[G]ranting social rights to enhance the integration of a hierarchical society, to forge a bond between workers and the state so as to strengthen the latter, to maintain traditional relations of authority between social and status groups, and to provide a countervailing power against the modernist forces of liberalism and socialism.[125]

Bismarck also enacted universal male suffrage in the new German Empire in 1871.[126] He became a great hero to German conservatives, who erected many monuments to his memory after he left office in 1890.[127]

With the rise of Nazism in 1933, agrarian movements faded and was supplanted by a more command-based economy and forced social integration. Though Adolf Hitler succeeded in garnering the support of many German industrialists, prominent traditionalists openly and secretly opposed his policies of euthanasia, genocide and attacks on organized religion, including Claus von Stauffenberg, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Henning von Tresckow, Bishop Clemens August Graf von Galen and the monarchist Carl Friedrich Goerdeler.

More recently, the work of conservative Christian Democratic Union leader and Chancellor Helmut Kohl helped bring about German reunification, along with the closer European integration in the form of the Maastricht Treaty.

.jpg.webp)

Today, German conservatism is often associated with politicians such as Chancellor Angela Merkel, whose tenure has been marked by attempts to save the common European currency (Euro) from demise. The German conservatives are divided under Merkel due to the refugee crisis in Germany and many conservatives in the CDU/CSU oppose the refugee and migrant policies developed under Merkel.[128]

Greece

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Greece |

|---|

|

The main inter-war conservative party was called the People's Party (PP), which supported constitutional monarchy and opposed the republican Liberal Party. Both it and the Liberal party were suppressed by the authoritarian, arch-conservative and royalist 4th of August Regime of Ioannis Metaxas in 1936–1941. The PP was able to re-group after the Second World War as part of a United Nationalist Front which achieved power campaigning on a simple anticommunist, nationalist platform during the Greek Civil War (1946–1949). However, the vote received by the PP declined during the so-called "Centrist Interlude" in 1950–1952. In 1952, Marshal Alexandros Papagos created the Greek Rally as an umbrella for the right-wing forces. The Greek Rally came to power in 1952 and remained the leading party in Greece until 1963—after Papagos' death in 1955 reformed as the National Radical Union under Konstantinos Karamanlis. Right-wing governments backed by the palace and the army overthrew the Centre Union government in 1965 and governed the country until the establishment of the far-right Greek junta (1967–1974). After the regime's collapse in August 1974, Karamanlis returned from exile to lead the government and founded the New Democracy party. The new conservative party had four objectives: to confront Turkish expansionism in Cyprus, to reestablish and solidify democratic rule, to give the country a strong government and to make a powerful moderate party a force in Greek politics.[129]

The Independent Greeks, a newly formed political party in Greece, has also supported conservatism, particularly national and religious conservatism. The Founding Declaration of the Independent Greeks strongly emphasises in the preservation of the Greek state and its sovereignty, the Greek people and the Greek Orthodox Church.[130]

Iceland

Founded in 1924 as the Conservative Party, Iceland's Independence Party adopted its current name in 1929 after the merger with the Liberal Party. From the beginning, they have been the largest vote-winning party, averaging around 40%. They combined liberalism and conservatism, supported nationalization of infrastructure and opposed class conflict. While mostly in opposition during the 1930s, they embraced economic liberalism, but accepted the welfare state after the war and participated in governments supportive of state intervention and protectionism. Unlike other Scandanivian conservative (and liberal) parties, it has always had a large working-class following.[131] After the financial crisis in 2008, the party has sunk to a lower support level around 20–25%.

Italy

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Italy |

|---|

|

After unification, Italy was governed successively by the Historical Right, which represented conservative, liberal-conservative and conservative-liberal positions, and the Historical Left. After World War I, the country saw the emergence of its first mass parties, notably including the Italian People's Party (PPI), a Christian-democratic party that sought to represent the Catholic majority, which had long refrained from politics. The PPI and the Italian Socialist Party decisively contributed to the loss of strength and authority of the old liberal ruling class, which had not been able to structure itself into a proper party: the Liberal Union was not a coherent one and the Italian Liberal Party came too late. In 1921 Benito Mussolini gave birth to the National Fascist Party (PNF), and the next year, through the March on Rome, he was appointed Prime Minister. In 1926 all parties were dissolved except the PNF, which thus remained the only legal party in the Kingdom of Italy until the fall of the regime in July 1943.

By 1945 Fascists were discredited,[132] disbanded and outlawed, while Mussolini was executed in April that year. After World War II, the centre-right was dominated by the centrist Christian Democracy (DC) party, which included both conservative and centre-left elements. With its landslide victory over the Italian Socialist Party and the Italian Communist Party in 1948, the political centre was in power. In Denis Mack Smith's words, it was "moderately conservative, reasonably tolerant of everything which did not touch religion or property, but above all Catholic and sometimes clerical." It dominated politics until DC's dissolution in 1994.[133][134] Among DC's frequent allies, there was the conservative-liberal Italian Liberal Party. At the right of the DC stood monarchist parties like the Monarchist National Party and the post-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI).

In 1994 entrepreneur and media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi founded Forza Italia (FI), a liberal-conservative party. Berlusconi won three elections in 1994, 2001 and 2008, governing the country for almost ten years as Prime Minister. FI formed a coalitions with several parties, including the national-conservative National Alliance (AN), heir of the MSI, and the regionalist Lega Nord (LN). FI was briefly incorporated, along with AN, in The People of Freedom party and later revived in the new Forza Italia.[135] After the 2018 general election, the LN and the Five Star Movement formed a populist government, which lasted about a year.[136] In the 2022 general election the centre-right coalition, this time dominated by Brothers of Italy (FdI), a new conservative party born on the ashes of AN. Consequently, FdI, the re-branded Lega and FI formed a government under FdI leader Giorgia Meloni.

Luxembourg

Luxembourg's major conservative party, the Christian Social People's Party (CSV or PCS), was formed as the Party of the Right in 1914 and adopted its present name in 1945. It was consistently the largest political party in Luxembourg, and dominated politics throughout the 20th century.[137]

Norway

The Conservative Party of Norway (Norwegian: Høyre, literally "right") was formed by the old upper class of state officials and wealthy merchants to fight the populist democracy of the Liberal Party, but lost power in 1884, when parliamentarian government was first practised. It formed its first government under parliamentarism in 1889 and continued to alternate in power with the Liberals until the 1930s, when Labour became the dominant political party. It has elements both of paternalism, stressing the responsibilities of the state, and of economic liberalism. It first returned to power in the 1960s.[138] During Kåre Willoch's premiership in the 1980s, much emphasis was laid on liberalizing the credit and housing market, and abolishing the NRK TV and radio monopoly, while supporting law and order in criminal justice and traditional norms in education[139]

Russia

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Russia |

|---|

|

Under Vladimir Putin, the dominant leader since 1999, Russia has promoted explicitly conservative policies in social, cultural and political matters, both at home and abroad.[140] Putin has criticized globalism and economic liberalism, claiming that "liberalism has become obsolete" and that the vast majority of people in the world oppose multiculturalism, free immigration, and rights for LGBT people.[141] Russian conservatism is special in some respects as it supports a mixed economy with economic intervention, combined with a strong nationalist sentiment and social conservatism which is largely populist. Russian conservatism as a result opposes libertarian ideals such as the aforementioned concept of economic liberalism found in other conservative movements around the world.

Putin has also promoted new think tanks that bring together like-minded intellectuals and writers. For example, the Izborsky Club, founded in 2012 by Alexander Prokhanov, stresses Russian nationalism, the restoration of Russia's historical greatness, and systematic opposition to liberal ideas and policies.[142] Vladislav Surkov, a senior government official, has been one of the key ideologists during Putin's presidency.[143]

In cultural and social affairs, Putin has collaborated closely with the Russian Orthodox Church. Under Patriarch Kirill of Moscow, the Church has backed the expansion of Russian power into Crimea and eastern Ukraine.[144] More broadly, The New York Times reports in September 2016 how the Church's policy prescriptions support the Kremlin's appeal to social conservatives:[145]

"A fervent foe of homosexuality and any attempt to put individual rights above those of family, community, or nation, the Russian Orthodox Church helps project Russia as the natural ally of all those who pine for a more secure, illiberal world free from the tradition-crushing rush of globalization, multiculturalism, and women's and gay rights."

— Andrew Higgins (The New York Times: "In Expanding Russian Influence, Faith Combines With Firepower")

Sweden

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Sweden |

|---|

|

Sweden's conservative party, the Moderate Party, was formed in 1904, two years after the founding of the Liberal Party.[146] The party emphasizes tax reductions, deregulation of private enterprise and privatization of schools, hospitals, and kindergartens.[147]

Switzerland

There are a number of conservative parties in Switzerland's parliament, the Federal Assembly. These include the largest, the Swiss People's Party (SVP),[148] the Christian Democratic People's Party (CVP)[149] and the Conservative Democratic Party of Switzerland (BDP),[150] which is a splinter of the SVP created in the aftermath to the election of Eveline Widmer-Schlumpf as Federal Council.[150] The right-wing parties have a majority in the Federal Assembly.

The Swiss People's Party (SVP or UDC) was formed from the 1971 merger of the Party of Farmers, Traders and Citizens, formed in 1917 and the smaller Swiss Democratic Party, formed in 1942. The SVP emphasized agricultural policy and was strong among farmers in German-speaking Protestant areas. As Switzerland considered closer relations with the European Union in the 1990s, the SVP adopted a more militant protectionist and isolationist stance. This stance has allowed it to expand into German-speaking Catholic mountainous areas.[151] The Anti-Defamation League, a non-Swiss lobby group based in the United States has accused them of manipulating issues such as immigration, Swiss neutrality and welfare benefits, awakening antisemitism and racism.[152] The Council of Europe has called the SVP "extreme right", although some scholars dispute this classification. For instance, Hans-Georg Betz describes it as "populist radical right".[153] The SVP is the largest party since 2003.

Ukraine

Authoritarian Ukrainian State headed by Pavlo Skoropadskyi represented the conservative movement. The 1918 Hetman government, which appealed to the tradition of the 17th–18th century Cossack Hetman state, represented the conservative strand in Ukraine's struggle for independence. It had the support of the proprietary classes and of conservative and moderate political groups. Vyacheslav Lypynsky was a main ideologue of Ukrainian conservatism.[154]

United Kingdom

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United Kingdom |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Part of the Politics series on |

| Toryism |

|---|

|

In Great Britain, the Tory movement during the Restoration period (1660–1688) was a primitive form of conservatism that supported a hierarchical society with a monarch who ruled by divine right. However, Tories differ from most later, more moderate, mainstream conservatives in that they opposed the idea that sovereignty derived from the people and rejected the authority of parliament and freedom of religion. Robert Filmer's Patriarcha: or the Natural Power of Kings (published posthumously in 1680, but written before the English Civil War of 1642–1651) became accepted as the statement of their doctrine. However, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 destroyed this principle to some degree by establishing a constitutional government in England, leading to the hegemony of the Tory-opposed Whig ideology. Faced with defeat, the Tories reformed their movement. They adopted more moderate conservative positions, such as holding that sovereignty was vested in the three estates of Crown, Lords, and Commons[155] rather than solely in the Crown. Richard Hooker (1554–1600), Marquess of Halifax (1633–1695) and David Hume (1711–1776) were conservatives of the period. Halifax promoted pragmatism in government whilst Hume argued against political rationalism and utopianism.[156][157]

According to historian James Sack, modern English conservatives celebrate Edmund Burke, who was Irish, as their intellectual father.[158] Burke was affiliated with the Whig Party which eventually split amongst the Liberal Party and the Conservative Party, but the modern Conservative Party is generally thought to derive primarily from the Tories, and the MPs of the modern conservative party are still frequently referred to as Tories.

Shortly after Burke's death in 1797, conservatism revived as a mainstream political force as the Whigs suffered a series of internal divisions. This new generation of conservatives derived their politics not from Burke, but from his predecessor, the Viscount Bolingbroke (1678–1751), who was a Jacobite and traditional Tory, lacking Burke's sympathies for Whiggish policies such as Catholic emancipation and American independence (famously attacked by Samuel Johnson in "Taxation No Tyranny"). In the first half of the 19th century, many newspapers, magazines, and journals promoted loyalist or right-wing attitudes in religion, politics and international affairs. Burke was seldom mentioned, but William Pitt the Younger (1759–1806) became a conspicuous hero. The most prominent journals included The Quarterly Review, founded in 1809 as a counterweight to the Whigs' Edinburgh Review and the even more conservative Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine. Sack finds that the Quarterly Review promoted a balanced Canningite toryism as it was neutral on Catholic emancipation and only mildly critical of Nonconformist Dissent; it opposed slavery and supported the current poor laws; and it was "aggressively imperialist". The high-church clergy of the Church of England read the Orthodox Churchman's Magazine which was equally hostile to Jewish, Catholic, Jacobin, Methodist and Unitarian spokesmen. Anchoring the ultra Tories, Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine stood firmly against Catholic emancipation and favoured slavery, cheap money, mercantilism, the Navigation Acts and the Holy Alliance.[159]

Conservatism evolved after 1820, embracing free trade in 1846 and a commitment to democracy, especially under Disraeli. The effect was to significantly strengthen conservatism as a grassroots political force. Conservatism no longer was the philosophical defense of the landed aristocracy, but had been refreshed into redefining its commitment to the ideals of order, both secular and religious, expanding imperialism, strengthened monarchy and a more generous vision of the welfare state as opposed to the punitive vision of the Whigs and liberals.[160] As early as 1835, Disraeli attacked the Whigs and utilitarians as slavishly devoted to an industrial oligarchy, while he described his fellow Tories as the only "really democratic party of England" and devoted to the interests of the whole people.[161] Nevertheless, inside the party there was a tension between the growing numbers of wealthy businessmen on the one side and the aristocracy and rural gentry on the other.[162] The aristocracy gained strength as businessmen discovered they could use their wealth to buy a peerage and a country estate.

Although conservatives opposed attempts to allow greater representation of the middle class in parliament, they conceded that electoral reform could not be reversed and promised to support further reforms so long as they did not erode the institutions of church and state. These new principles were presented in the Tamworth Manifesto of 1834, which historians regard as the basic statement of the beliefs of the new Conservative Party.[163]

.jpg.webp)

Some conservatives lamented the passing of a pastoral world where the ethos of noblesse oblige had promoted respect from the lower classes. They saw the Anglican Church and the aristocracy as balances against commercial wealth.[164] They worked toward legislation for improved working conditions and urban housing.[165] This viewpoint would later be called Tory democracy.[166] However, since Burke, there has always been tension between traditional aristocratic conservatism and the wealthy business class.[167]

In 1834, Tory Prime Minister Robert Peel issued the Tamworth Manifesto in which he pledged to endorse moderate political reform. This marked the beginning of the transformation of British conservatism from High Tory reactionism towards a more modern form based on "conservation". The party became known as the Conservative Party as a result, a name it has retained to this day. However, Peel would also be the root of a split in the party between the traditional Tories (by the Earl of Derby and Benjamin Disraeli) and the "Peelites" (led first by Peel himself, then by the Earl of Aberdeen). The split occurred in 1846 over the issue of free trade, which Peel supported, versus protectionism, supported by Derby. The majority of the party sided with Derby whilst about a third split away, eventually merging with the Whigs and the radicals to form the Liberal Party. Despite the split, the mainstream Conservative Party accepted the doctrine of free trade in 1852.

In the second half of the 19th century, the Liberal Party faced political schisms, especially over Irish Home Rule. Leader William Gladstone (himself a former Peelite) sought to give Ireland a degree of autonomy, a move that elements in both the left and right-wings of his party opposed. These split off to become the Liberal Unionists (led by Joseph Chamberlain), forming a coalition with the Conservatives before merging with them in 1912. The Liberal Unionist influence dragged the Conservative Party towards the left as Conservative governments passing a number of progressive reforms at the turn of the 20th century. By the late 19th century, the traditional business supporters of the Liberal Party had joined the Conservatives, making them the party of business and commerce.[168]

After a period of Liberal dominance before the First World War, the Conservatives gradually became more influential in government, regaining full control of the cabinet in 1922. In the inter-war period, conservatism was the major ideology in Britain[169][170][171] as the Liberal Party vied with the Labour Party for control of the left. After the Second World War, the first Labour government (1945–1951) under Clement Attlee embarked on a program of nationalization of industry and the promotion of social welfare. The Conservatives generally accepted those policies until the 1980s.

.jpg.webp)

In the 1980s, the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher, guided by neoliberal economics, reversed many of Labour's social programmes, privatised large parts of the UK economy and sold state-owned assets.[172] The Conservative Party also adopt soft eurosceptic politics, and oppose Federal Europe. Other conservative political parties, such as the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP, founded in 1993), Northern Ireland's Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) and the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP, founded in 1971), began to appear, although they have yet to make any significant impact at Westminster (as of 2014, the DUP comprises the largest political party in the ruling coalition in the Northern Ireland Assembly), and from 2017–19 the DUP provided support for the Conservative minority government under a confidence-and-supply arrangement.

Latin America

Conservative elites have long dominated Latin American nations. Mostly, this has been achieved through control of and support for civil institutions, the church and the armed forces, rather than through party politics. Typically, the church was exempt from taxes and its employees immune from civil prosecution. Where national conservative parties were weak or non-existent, conservatives were more likely to rely on military dictatorship as a preferred form of government. However, in some nations where the elites were able to mobilize popular support for conservative parties, longer periods of political stability were achieved. Chile, Colombia and Venezuela are examples of nations that developed strong conservative parties. Argentina, Brazil, El Salvador and Peru are examples of nations where this did not occur.[173] The Conservative Party of Venezuela disappeared following the Federal Wars of 1858–1863.[174] Chile's conservative party, the National Party, disbanded in 1973 following a military coup and did not re-emerge as a political force following the subsequent return to democracy.[175] Louis Hartz explained conservatism in Quebec and Latin America as a result of their settlement as feudal societies.[176]

Brazil

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Brazil |

|---|

|

.jpg.webp)

Conservatism in Brazil originates from the cultural and historical tradition of Brazil, whose cultural roots are Luso-Iberian and Roman Catholic.[177] More traditional conservative historical views and features include belief in political federalism and monarchism.

In cultural life, Brazilian conservatism from the 20th century on includes names such as Mário Ferreira dos Santos and Vicente Ferreira da Silva in philosophy; Gerardo Melo Mourão and Otto Maria Carpeaux in literature; Bruno Tolentino in poetry; Olavo de Carvalho, Paulo Francis and Luís Ernesto Lacombe in journalism; Manuel de Oliveira Lima and João Camilo de Oliveira Torres in historiography; Sobral Pinto and Miguel Reale in law; Gustavo Corção, Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Father Léo and Father Paulo Ricardo[178] in the Catholic Church; and Roberto Campos and Mario Henrique Simonsen in economics.[179]

In contemporary politics, a conservative wave began roughly around the 2014 Brazilian presidential election.[180] According to political analyst Antônio Augusto de Queiroz, the National Congress of Brazil elected in 2014 may be considered the most conservative since the re-democratization movement, citing an increase in the number of parliamentarians linked to more conservative segments, such as ruralists, the military of Brazil, police of Brazil, and religious conservatives. The subsequent economic crisis of 2015 and investigations of corruption scandals led to a right-wing movement that sought to rescue ideas from economic liberalism and conservatism in opposition to socialism. At the same time, fiscal conservatives such as those that make up the Free Brazil Movement emerged among many others. National conservative candidate Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party was the winner of the 2018 Brazilian presidential election.[181]

Brazil Union, Progressistas, Republicans, Liberal Party, Brazilian Labour Renewal Party, Patriota, Brazilian Labour Party, Social Christian Party and Brasil 35 are the conservative parties in Brazil.

Colombia

The Colombian Conservative Party, founded in 1849, traces its origins to opponents of General Francisco de Paula Santander's 1833–1837 administration. While the term "liberal" had been used to describe all political forces in Colombia, the conservatives began describing themselves as "conservative liberals" and their opponents as "red liberals". From the 1860s until the present, the party has supported strong central government; supported the Catholic Church, especially its role as protector of the sanctity of the family; and opposed separation of church and state. Its policies include the legal equality of all men, the citizen's right to own property and opposition to dictatorship. It has usually been Colombia's second largest party, with the Colombian Liberal Party being the largest.[182]

North America

Canada

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Canada |

|---|

|

|

|

Canada's conservatives had their roots in the Tory loyalists who left America after the American Revolution. They developed in the socio-economic and political cleavages that existed during the first three decades of the 19th century and had the support of the business, professional and established Church (Anglican) elites in Ontario and to a lesser extent in Quebec. Holding a monopoly over administrative and judicial offices, they were called the "Family Compact" in Ontario and the "Chateau Clique" in Quebec. John A. Macdonald's successful leadership of the movement to confederate the provinces and his subsequent tenure as prime minister for most of the late 19th century rested on his ability to bring together the English-speaking Protestant oligarchy and the ultramontane Catholic hierarchy of Quebec and to keep them united in a conservative coalition.[183]

The conservatives combined pro-market liberalism and Toryism. They generally supported an activist government and state intervention in the marketplace and their policies were marked by noblesse oblige, a paternalistic responsibility of the elites for the less well-off.[184] From 1942, the party was known as the Progressive Conservatives until 2003, when the national party merged with the Canadian Alliance to form the Conservative Party of Canada.[185]

The conservative and autonomist Union Nationale, led by Maurice Duplessis, governed the province of Quebec in periods from 1936 to 1960 and in a close alliance with the Catholic Church, small rural elites, farmers and business elites. This period, known by liberals as the Great Darkness, ended with the Quiet Revolution and the party went into terminal decline.[186] By the end of the 1960s, the political debate in Quebec centered around the question of independence, opposing the social democratic and sovereignist Parti Québécois and the centrist and federalist Quebec Liberal Party, therefore marginalizing the conservative movement. Most French Canadian conservatives rallied either the Quebec Liberal Party or the Parti Québécois, while some of them still tried to offer an autonomist third-way with what was left of the Union Nationale or the more populists Ralliement créditiste du Québec and Parti national populaire, but by the 1981 provincial election politically organized conservatism had been obliterated in Quebec. It slowly started to revive at the 1994 provincial election with the Action démocratique du Québec, who served as Official opposition in the National Assembly from 2007 to 2008, before its merger with François Legault's Coalition Avenir Québec in 2012, that took power in 2018.

The modern Conservative Party of Canada has rebranded conservatism and under the leadership of Stephen Harper, the Conservative Party added more conservative policies.

United States

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

The meaning of conservatism in the United States is different from the way the word is used elsewhere. As historian Leo P. Ribuffo notes, "what Americans now call conservatism much of the world calls liberalism or neoliberalism".[187] However, the prominent American conservative writer Russell Kirk, in his influential work The Conservative Mind (1953), argued that conservatism had been brought to the United States and he interpreted the American Revolution as a "conservative revolution".[188]

American conservatism is a broad system of political beliefs in the United States that is characterized by respect for American traditions, support for Judeo-Christian values, economic liberalism, anti-communism, and a defense of Western culture. Liberty within the bounds of conformity to conservatism is a core value, with a particular emphasis on strengthening the free market, limiting the size and scope of government and opposition to high taxes and government or labor union encroachment on the entrepreneur.

The 1830s Democratic Party became divided between Southern Democrats, who supported slavery, secession, and later segregation, and the Northern Democrats, who tended to support the abolition of slavery, union, and equality.[189] Many Democrats were conservative in the sense that they wanted things to be like they were in the past, especially as far as race was concerned. They generally favored poorer farmers and urban workers, and were hostile to banks and industrialization and high tariffs.[190]

The post-Civil War Republican Party elected the first People of Color to serve in both local and national political office. The Southern Democrats united with pro-segregation Northern Republicans to form the Conservative Coalition, which successfully put an end to Blacks being elected to national political office until 1967, when Edward Brooke was elected Senator from Massachusetts.[191][192]

In late 19th century, the Democratic Party split into two factions; the more conservative Eastern business faction (led by Grover Cleveland) favored gold, while the South and West (led by William Jennings Bryan) wanted more silver in order to raise prices for their crops. In 1892, Cleveland won the election on a conservative platform, which supported maintaining the gold standard, reducing tariffs, and taking a laisse-faire approach to government intervention. A severe nationwide depression ruined his plans. Many of his supporters in 1896 supported the Gold Democrats when liberal William Jennings Bryan won the nomination and campaigned for bimetalism, money backed by both gold and silver. The conservative wing nominated Alton B. Parker in 1904, but he got very few votes.[193][194]

Since the 1920s, conservatism in the United States has been chiefly associated with the Republican Party. During the era of segregation, many Southern Democrats were conservatives and they played a key role in the conservative coalition that largely controlled domestic policy in Congress from 1937 to 1963.[195] The conservative Democrats continued to have influence in the US politics until 1994's Republican Revolution, when the American South shifted from solid Democrat to solid Republican, while maintaining its conservative values.

.jpg.webp)

The major conservative party in the United States today is the Republican Party, also known as the GOP (Grand Old Party). Modern American conservatives consider individual liberty, as long as it conforms to conservative values, small government, deregulation of the government, economic liberalism, and free trade, as the fundamental trait of democracy, which contrasts with modern American liberals, who generally place a greater value on social equality and social justice.[196][197] Other major priorities within American conservatism include support for the traditional family, law and order, the right to bear arms, Christian values, anti-communism and a defense of "Western civilization from the challenges of modernist culture and totalitarian governments".[198] Economic conservatives and libertarians favor small government, low taxes, limited regulation and free enterprise. Some social conservatives see traditional social values threatened by secularism, so they support school prayer and oppose abortion and homosexuality.[199] Neoconservatives want to expand American ideals throughout the world and show a strong support for Israel.[200] Paleoconservatives, in opposition to multiculturalism, press for restrictions on immigration.[201] Most US conservatives prefer Republicans over Democrats and most factions favor a strong foreign policy and a strong military. The conservative movement of the 1950s attempted to bring together these divergent strands, stressing the need for unity to prevent the spread of "godless communism", which Reagan later labeled an "evil empire".[202][203] During the Reagan administration, conservatives also supported the so-called "Reagan Doctrine" under which the US as part of a Cold War strategy provided military and other support to guerrilla insurgencies that were fighting governments identified as socialist or communist. The Reagan administration also adopted neoliberalism and Reaganomics (pejoratively referred to as trickle-down economics), resulting in the 1980s economic growth and trillion-dollar deficits.

Other modern conservative positions include opposition to big government and opposition to environmentalism.[204] On average, American conservatives desire tougher foreign policies than liberals do.[205] Economic liberalism, deregulation and social conservatism are major principles of the Republican Party.

The Tea Party movement, founded in 2009, had proven a large outlet for populist American conservative ideas. Their stated goals included rigorous adherence to the US constitution, lower taxes, and opposition to a growing role for the federal government in health care. Electorally, it was considered a key force in Republicans reclaiming control of the US House of Representatives in 2010.[206][207][208]

Australia

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Australia |

|---|

|

The Liberal Party of Australia adheres to the principles of social conservatism and liberal conservatism.[209] It is liberal in the sense of economics. Other conservative parties are the National Party of Australia, a sister party of the Liberals, Family First Party, Democratic Labor Party, Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party, Australian Conservatives, and the Katter's Australian Party.

The largest party in the country is the Australian Labor Party and its dominant faction is Labor Right, a socially conservative element. Australia undertook significant economic reform under the Labor Party in the mid-1980s. Consequently, issues like protectionism, welfare reform, privatization and deregulation are no longer debated in the political space as they are in Europe or North America. Moser and Catley explain: "In America, 'liberal' means left-of-center, and it is a pejorative term when used by conservatives in adversarial political debate. In Australia, of course, the conservatives are in the Liberal Party."[210] Jupp writes that "[the] decline in English influences on Australian reformism and radicalism, and appropriation of the symbols of Empire by conservatives continued under the Liberal Party leadership of Sir Robert Menzies, which lasted until 1966".[211]

Psychology

Conscientiousness

The Big Five Personality Model has applications in the study of political psychology. It has been found by several studies that individuals who score high in Conscientiousness (the quality of working hard and being careful) are more likely to possess a right-wing political identification.[212][213][214] On the opposite end of the spectrum, a strong correlation was identified between high scores in Openness to Experience and a left-leaning ideology.[212][215][216] Because conscientiousness is positively related to job performance,[217][218] a 2021 study found that conservative service workers earn higher ratings, evaluations, and tips than social liberal ones.[219]

Disgust sensitivity

A number of studies have found that disgust is tightly linked to political orientation. People who are highly sensitive to disgusting images are more likely to align with the political right and value traditional ideals of bodily and spiritual purity, tending to oppose, for example, abortion and gay marriage.[220][221][222][223]

Research has also found that people who are more disgust sensitive tend to favour their own in-group over out-groups. The reason behind this may be that people begin to associate outsiders with disease while associating health with people similar to themselves.[224]

The higher one's disgust sensitivity is, the greater the tendency to make more conservative moral judgments. Disgust sensitivity is associated with moral hypervigilance, which means people who have higher disgust sensitivity are more likely to think that suspects of a crime are guilty. They also tend to view them as evil, if found guilty, thus endorsing them to harsher punishment in the setting of a court.[225]

Authoritarianism

Following the Second World War, psychologists conducted research into the different motives and tendencies that account for ideological differences between left and right. The early studies focused on conservatives, beginning with Theodor W. Adorno's The Authoritarian Personality (1950) based on the F-scale personality test. This book has been heavily criticized on theoretical and methodological grounds, but some of its findings have been confirmed by further empirical research.[226]

According to psychologist Bob Altemeyer, individuals who are politically conservative tend to rank high in right-wing authoritarianism (RWA) on his RWA scale.[227] This finding was echoed by Adorno. A study done on Israeli and Palestinian students in Israel found that RWA scores of right-wing party supporters were significantly higher than those of left-wing party supporters.[228] However, a 2005 study by H. Michael Crowson and colleagues suggested a moderate gap between RWA and other conservative positions, stating that their "results indicated that conservatism is not synonymous with RWA."[229]

Ambiguity intolerance

In 1973, British psychologist Glenn Wilson published an influential book providing evidence that a general factor underlying conservative beliefs is "fear of uncertainty."[230] A meta-analysis of research literature by Jost, Glaser, Kruglanski, and Sulloway in 2003 found that many factors, such as intolerance of ambiguity and need for cognitive closure, contribute to the degree of one's political conservatism and its manifestations in decision-making.[226][231] A study by Kathleen Maclay stated these traits "might be associated with such generally valued characteristics as personal commitment and unwavering loyalty". The research also suggested that while most people are resistant to change, social liberals are more tolerant of it.[232]

Social dominance orientation

Social dominance orientation (SDO) is a personality trait measuring an individual's support for social hierarchy and the extent to which they desire their in-group be superior to out-groups. Psychologist Felicia Pratto and her colleagues have found evidence to support the claim that a high SDO is strongly correlated with conservative views and opposition to social engineering to promote equality.[233] Pratto and her colleagues also found that high SDO scores were highly correlated with measures of prejudice.

However, David J. Schneider argued for a more complex relationships between the three factors, writing that "correlations between prejudice and political conservatism are reduced virtually to zero when controls for SDO are instituted, suggesting that the conservatism–prejudice link is caused by SDO".[234] Conservative political theorist Kenneth Minogue criticized Pratto's work, saying:

It is characteristic of the conservative temperament to value established identities, to praise habit and to respect prejudice, not because it is irrational, but because such things anchor the darting impulses of human beings in solidities of custom which we do not often begin to value until we are already losing them. Radicalism often generates youth movements, while conservatism is a condition found among the mature, who have discovered what it is in life they most value.[235]

A 1996 study by Pratto and her colleagues examined the topic of racism. Contrary to what these theorists predicted, correlations among conservatism and racism were strongest among the most educated individuals, and weakest among the least educated. They also found that the correlation between racism and conservatism could be accounted for by their mutual relationship with SDO.[236]

Happiness

In his book Gross National Happiness (2008), Arthur C. Brooks presents the finding that conservatives are roughly twice as happy as social liberals.[237] A 2008 study suggested that conservatives tend to be happier than social liberals because of their tendency to justify the current state of affairs and to remain unbothered by inequalities in society.[238] A 2012 study disputed this, demonstrating that conservatives expressed greater personal agency (e.g., personal control, responsibility), more positive outlook (e.g., optimism, self-worth), and more transcendent moral beliefs (e.g., greater religiosity, greater moral clarity).[239]

See also

National variants

- Conservatism in Australia

- Conservatism in Bangladesh

- Conservatism in Brazil

- Conservatism in Canada

- Conservatism in Colombia

- Conservatism in Germany

- Conservatism in Hong Kong

- Conservatism in India

- Conservatism in Malaysia

- Conservatism in New Zealand

- Conservatism in Pakistan

- Conservatism in Peru

- Conservatism in Russia

- Conservatism in Serbia

- Conservatism in South Korea

- Conservatism in Taiwan

- Conservatism in Turkey

- Conservatism in the United Kingdom

- Conservatism in the United States

Ideological variants

- Black conservatism

- Corporatist conservatism

- Cultural conservatism

- Feminist conservatism

- Fiscal conservatism

- Green conservatism

- LGBT conservatism

- Liberal conservatism

- Libertarian conservatism

- Moderate conservatism

- National conservatism

- Neoconservatism

- Paternalistic conservatism

- Pragmatic conservatism

- Progressive conservatism

- Populist conservatism

- Social conservatism

- Traditionalist conservatism

- Ultraconservatism

References

- Yoram Hazony (2022). Conservatism: A Rediscovery. Swift Press. pp. 142–153. ISBN 9781800752344.

- Hamilton, Andrew (2019). "Conservatism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Conservatism". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- Frank O'Gorman (2003). Edmund Burke: His Political Philosophy. Routledge. p. 171. ISBN 978-0-415-32684-1.

- Jerry Z. Muller, ed. (1997). Conservatism: An Anthology of Social and Political Thought from David Hume to the Present. Princeton U.P. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-691-03711-0.

Terms related to 'conservative' first found their way into political discourse in the title of the French weekly journal, Le Conservateur, founded in 1818 by François-René de Chateaubriand with the aid of Louis de Bonald.

- Heywood 2012, p. 66.

- Vincent 2009, p. 79.

- Winthrop and Lovell, pp. 163–166

- Quintin Hogg Baron Hailsham of St. Marylebone (1959). The Conservative Case. Penguin Books.

- Oakeshott, Michael (1962). Rationalism in Politics and Other Essays. London: Methuen. pp. 168–196.

- Heywood 2017, p. 66.

- Robin, Corey (January 8, 2012). "The Conservative Mind". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved December 23, 2016.

- Henning Finseraas, "What if Robin Hood is a social conservative? How the political response to increasing inequality depends on party polarization." Socio-Economic Review 8.2 (2010): 283–306.

- Farrell, Henry (February 1, 2018). "Trump is a typical conservative. That says a lot about the conservative tradition". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- Yoram Hazony (2022). Conservatism: A Rediscovery. Swift Press. pp. 125–133. ISBN 9781800752344.

- "hierarchy". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Heywood 2017, p. 67.

- Fawcett, Edmund (October 20, 2020). Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-17410-5.