Cross-Strait relations

Cross-Strait relations (sometimes called Mainland–Taiwan relations,[1] China–Taiwan relations or Taiwan–China relations[2]) are the relations between China (officially the People's Republic of China, PRC) and Taiwan (officially the Republic of China, ROC).

| |

China |

Taiwan |

|---|---|

| Cross-Strait relations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 海峽兩岸關係 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 海峡两岸关系 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The relationship has been complex and controversial due to the dispute on the political status of Taiwan after the administration of Taiwan was transferred from Japan to the Republic of China at the end of World War II in 1945, and the subsequent split between the PRC and ROC as a result of the Chinese Civil War. The essential question is whether the two governments are still in a civil war over One China, each holding within one of two "regions" or parts of the same country (e.g. "1992 Consensus"), whether they can be reunified as one country, two systems, or whether they are now separate countries (either as "Taiwan" and "China" or Two Chinas). The English expression "cross-strait relations" is considered to be a neutral term that avoids reference to the political status of either side.

At the end of World War II in 1945, the administration of Taiwan was transferred to the Republic of China (ROC) from the Empire of Japan, though legal questions remain regarding the language in the Treaty of San Francisco. In 1949, with the Chinese Civil War turning decisively in favor of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the Republic of China government, led by the Kuomintang (KMT), retreated to Taiwan and established the provisional capital in Taipei, while the CCP proclaimed the People's Republic of China (PRC) government in Beijing. No armistice or peace treaty has ever been signed and debate continues as to whether the civil war has legally ended.[3]

Since then, the relations between the governments in Beijing and Taipei have been characterized by limited contact, tensions, and instability. In the early years, military conflicts continued, while diplomatically both governments competed to be the "legitimate government of China". Since the democratization of Taiwan, the question regarding the political and legal status of Taiwan has shifted focus to the choice between political unification with mainland China or de jure Taiwanese independence. The PRC remains hostile to any formal declaration of independence and maintains its claim over Taiwan.

At the same time, non-governmental and semi-governmental exchanges between the two sides have increased. In 2008, negotiations began to restore the Three Links (postal, transportation, trade) between the two sides, cut off since 1949. Diplomatic contact between the two sides has generally been limited to Kuomintang administrations on Taiwan. However, during Democratic Progressive Party administrations, negotiations continue to occur on practical matters through informal channels.[4]

History

Timeline

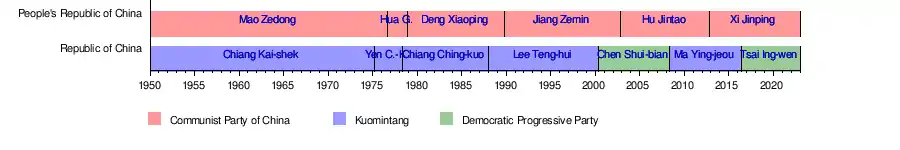

Leaders of the two governments

Before 1949

The early history of cross-strait relations involved the exchange of cultures, people, and technology.[5][6][7] However, no Chinese dynasty formally incorporated Taiwan in ancient times.[8] In the 16th and 17th centuries, Taiwan first caught the attention of Portuguese, then Dutch and Spanish explorers. After establishing their first settlement in Taiwan in 1624, the Dutch were defeated in 1662 by Koxinga (Zheng Chenggong), a Ming dynasty loyalist, who took the island and established the first formally Han Chinese regime in Taiwan. Koxinga's heirs used Taiwan as a base for launching raids into mainland China against the Manchu Qing dynasty, before being defeated in 1683 by Qing forces. Taiwan was incorporated into Fujian province in 1684.

With other powers increasingly eyeing Taiwan for its strategic location and resources in the 19th century, the administration began to implement a modernization drive.[9] In 1887, Fujian-Taiwan Province was declared by Imperial decree. However, the fall of the Qing outpaced the development of Taiwan, and in 1895, following its defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, the Imperial government ceded Taiwan to Japan in perpetuity. Qing loyalists briefly resisted the Japanese rule under the banner of the "Republic of Formosa", but were quickly put down by Japanese authorities.[10]

Japan ruled Taiwan until 1945. As part of the Japanese Empire, Taiwan was a foreign jurisdiction in relation to the Qing dynasty until 1912, and then to the Republic of China for the remainder of the Japanese rule. In 1945, Japan was defeated in World War II and surrendered its forces in Taiwan to the Allies; the ROC, then ruled by the Kuomintang (KMT), took custody of the island. The period of post-war KMT rule over China (1945–1949) was marked by conflict in Taiwan between local residents and the new KMT authority. The Taiwanese rebelled on 28 February 1947, but the uprising was violently suppressed by the KMT. The seeds for the Taiwan independence movement were sown during this period.

China was soon engulfed in full-scale civil war. In 1949, the conflict turned decisively against the KMT and in favor of the CCP. On 1 October 1949, CCP Chairman Mao Zedong proclaimed the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC) in Beijing. The capitalist ROC government retreated to Taiwan, eventually declaring Taipei its temporary capital in December 1949.[11]

Kuomintang's retreat

In June 1949, the ROC declared a "closure" of all Chinese ports and its navy attempted to intercept all foreign ships. The closure covered from a point north of the mouth of Min river in Fujian province to the mouth of the Liao River in Manchuria.[12] Since China's railroad network was underdeveloped, north–south trade depended heavily on sea lanes. ROC naval activity also caused severe hardship for Chinese fishermen.

The two governments continued in a state of war until 1979. In October 1949, the PRC's attempt to take the ROC-controlled island of Kinmen was thwarted in the Battle of Kuningtou, halting the advance of the PRC's People's Liberation Army (PLA) towards Taiwan.[13] In the Battle of Dengbu Island on 3 November 1949, the ROC forces repulsed their PRC counterparts, but were later forced to retreat after the PRC gained air superiority.[14] The ROC government also launched a number of air bombing raids into key coastal cities of China such as Shanghai.[15] The Communists' other amphibious operations of 1950 were more successful: they led to the Communist conquest of Hainan Island in April 1950, capture of Wanshan Islands off the Guangdong coast (May–August 1950) and of Zhoushan Island off Zhejiang (May 1950).[16] The same result happened in the Battle of Dongshan Island on 11 May 1950, as well as the Battle of Nanpeng Island in September and October of the same year. However, supported by the US, the ROC won the Battle of Nanri Island in 1952. Later in the year, the communists won the Battle of Nanpeng Archipelago, as well as the Battle of Dalushan Islands and the Dongshan Island Campaign, both in 1953.

After losing mainland China, a group of approximately 12,000 KMT soldiers escaped to Burma and continued launching guerrilla attacks into southern China in the early 1950s.[17] Their leader, General Li Mi, was paid a salary by the ROC government and given the nominal title of Governor of Yunnan. Initially, the United States supported these remnants and the Central Intelligence Agency provided them with aid. After the Burmese government appealed to the United Nations in 1953, the U.S. began pressuring the ROC to withdraw its loyalists. By the end of 1954, nearly 6,000 soldiers had left Burma and Li Mi declared his army disbanded. However, thousands remained, and the ROC continued to supply and command them, even secretly supplying reinforcements at times. In northwestern China, the Kuomintang Islamic insurgency was fought by Muslim Kuomintang army officers who refused to surrender to the Communists throughout the 1950s and 1960s.

Korean War and Taiwan Strait Crises

Most observers expected Chiang's government to eventually fall in response to a Communist invasion of Taiwan, and the U.S. initially showed no interest in supporting Chiang's government in its final stand. Things changed radically with the onset of the Korean War in June 1950. At this point, it became politically impossible in the U.S. to allow a total Communist victory over Chiang, so President Harry S. Truman ordered the U.S. Seventh Fleet into the Taiwan Strait to prevent the ROC and PRC from attacking each other.[18] The U.S. fleet hindered the Communist invasion of Taiwan, and the PRC decided to send troops to Korea in October 1950.[19] The ROC proposed to participate in the Korean War, but was rejected.[20] During the Korean War, some captured Communist Chinese soldiers, many of whom were originally KMT soldiers, were repatriated to Taiwan rather than China.[21][22][23]

Though viewed as a military liability by the United States, the ROC viewed its remaining islands in Fujian as vital for any future campaign to defeat the PRC and retake China. On 3 September 1954, the First Taiwan Strait Crisis began when the PLA started shelling Kinmen and threatened to take the Dachen Islands.[12] On 20 January 1955, the PLA took nearby Yijiangshan Island, with the entire ROC garrison of 720 troops killed or wounded defending the island. On 24 January, the U.S. Congress passed the Formosa Resolution authorizing the President to defend the ROC's offshore islands.[12] The First Taiwan Strait Crisis ended in March 1955 when the PLA ceased its bombardment. The crisis was brought to a close during the Bandung conference.[12] At the conference, China articulated its Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence and Premier Zhou Enlai publicly stated, "[T]he Chinese people do not want to have a war with the United States. The Chinese government is willing to sit down to discuss the question of relaxing tension in the Far East, and especially the question of relaxing tension in the Taiwan area."[24] Two years of negotiations with the U.S. followed, although no agreement was reached on the Taiwan issue.[24]

The Second Taiwan Strait Crisis began on 23 August 1958 with air and naval engagements between the PRC and the ROC military forces, leading to intense artillery bombardment of Kinmen (by the PRC) and Xiamen (by the ROC), and ended in November of the same year.[12] PLA patrol boats blockaded the islands from ROC supply ships. Though the U.S. rejected Chiang Kai-shek's proposal to bomb Chinese artillery batteries, it quickly moved to supply fighter jets and anti-aircraft missiles to the ROC. It also provided amphibious assault ships to land supply, as a sunken ROC naval vessel was blocking the harbor. On 7 September, the U.S. escorted a convoy of ROC supply ships and the PRC refrained from firing. On 25 October, the PRC announced an "even-day ceasefire" — the PLA would only shell Kinmen on odd-numbered days.

After the crises

After the 1950s, the "war" became more symbolic than real, represented by on again, off again artillery bombardment towards and from Kinmen. In later years, live shells were replaced with propaganda sheets.[25] The ROC once initiated Project National Glory, a plan to retake mainland China.[26] The project failed in the 1960s,[27] and the bombardment finally ceased after the establishment of diplomatic relations between the PRC and the United States.[25] The PRC and the ROC have never signed any agreement or treaty to officially end the war.[28] There were occasional defectors from both sides.[29][30]

Diplomatically during this period, until around 1971, the ROC government continued to be recognized as the legitimate government of China and Taiwan by most NATO governments. The PRC government was recognized by Soviet Bloc countries, members of the Non-Aligned Movement, and some Western nations such as the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Both governments claimed to be the legitimate government of China, and labeled the other as illegitimate. Civil war propaganda permeated the education curriculum. Each side portrayed the people of the other as living in hell-like misery. In official media, each side called the other "bandits". The ROC also suppressed expressions of support for Taiwanese identity or Taiwan independence.

Thawing of relations (1979–1998)

After the United States formally recognized the PRC and broke its official relations with the ROC in 1979, the PRC under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping shifted its strategy from liberating Taiwan to peaceful unification, with a formula of "one country, two systems."[31] The ROC government under Chiang Ching-kuo maintained a "Three Noes" policy of no contact, no negotiation and no compromise to deal with the PRC government. However, Chiang was forced to break from this policy during the May 1986 hijacking of a China Airlines cargo plane, in which the Taiwanese pilot subdued other members of the crew and flew the plane to Guangzhou. In response, Chiang sent delegates to Hong Kong to discuss with PRC officials for the return of the plane and crew, which is seen as a turning point between cross-strait relations.[32][33]

In 1987, the ROC government began to allow visits to China. This benefited many, especially old KMT soldiers, who had been separated from their family in China for decades.[34][35] This also proved a catalyst for the thawing of relations between the two sides. Problems engendered by increased contact necessitated a mechanism for regular negotiations. In 1988, a guideline was approved by PRC to encourage ROC investments in the PRC.[36][37] It guaranteed ROC establishments would not be nationalized, and that exports were free from tariffs, ROC businessmen would be granted multiple visas for easy movement.

In order to negotiate with China on operational issues without compromising the government's position on denying the other side's legitimacy, the ROC government under Lee Teng-hui created the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF), a nominally non-governmental institution directly led by the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC), an instrument of the Executive Yuan in 1991. The PRC responded to this initiative by setting up the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS), directly led by the Taiwan Affairs Office of the State Council. This system, described as "white gloves", allowed the two governments to engage with each other on a semi-official basis without compromising their respective sovereignty policies.[38] Led by Koo Chen-fu and Wang Daohan, the two organizations began a series of talks that culminated in the 1993 Wang–Koo summit while both sides agreed to deliberate ambiguity on questions of sovereignty in order to engage on operational questions affecting both sides.[39]

Also during this time, however, the rhetoric of ROC President Lee Teng-hui began to turn further towards Taiwan independence.[40] Prior to the 1990s, the ROC had been a one-party authoritarian state committed to eventual unification with China. However, with democratic reforms the attitudes of the general public began to influence policy in Taiwan. As a result, the ROC government shifted away from its commitment to the One China and towards a separate political identity for Taiwan. In 1995, Lee visited the United States and delivered a speech to an invited audience at Cornell University.[41] In response to Taiwan's diplomatic moves, the PRC postponed the second Wang–Koo summit indefinitely.[42] The PLA attempted to influence the 1996 Taiwanese presidential election by conducting a missile exercise, leading to the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis.[43][44]

Hostile non-contact (1998–2008)

In 1998, the ARATS and the SEF resumed contact and the second Wang–Koo summit was held in Shanghai, China.[45] The PRC leader Jiang Zemin also received the Taiwanese representatives in Beijing. While Wang Daohan's return visit to Taiwan was scheduled, Lee Teng-hui described cross-Strait relations as "state-to-state or at least special state-to-state relations" in July 1999.[46] Lee's "two-state" theory postponed Wang's visit indefinitely and the PRC issued a white paper entitled "The One-China Principle and the Taiwan Issue" in February 2000, before the 2000 Taiwanese presidential election.[47]

Chen Shui-bian of the pro-independence Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) was elected President of the ROC in 2000. Before the KMT handed over power to the DPP, chairman of the Mainland Affairs Council Su Chi suggested a new term “1992 Consensus” as a common point that was acceptable to both sides so that Taiwan and China could keep up cross-strait exchanges.[48] Chen expressed some willingness to accept the 1992 Consensus, but backed down after backlash within his own party.[49] In his inaugural speech, Chen Shui-bian pledged to the Four Noes and One Without, in particular, promising to seek neither independence nor unification as well as rejecting the concept of special state-to-state relations expressed by his predecessor, Lee Teng-hui, as well as establishing the Three Mini-Links. Furthermore, he pursued a policy of normalizing economic relations with the PRC.[50] The PRC did not engage Chen's administration, but meanwhile in 2001 Chen lifted the 50-year ban on direct trade and investment with the PRC.[51][52] In November 2001, Chen repudiated "One China" and called for talks without preconditions.[53]

Hu Jintao became General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party in late 2002, succeeding Jiang Zemin as de facto top leader of China. Hu continued to insist that talks can only proceed under an agreement of the "One China" principle. At the same time, Hu and the PRC continued a military missile buildup across the strait from Taiwan while making threats of military action against Taiwan should it declare independence or if the PRC considers that all possibilities for a peaceful unification are completely exhausted. The PRC also continued applying diplomatic pressure to other nations to isolate the ROC diplomatically. However, during the 2003 Iraq war, the PRC allowed Taiwanese airlines use of China's airspace.[54]

After the re-election of Chen Shui-bian in 2004, Hu's government changed the previous blanket no-contact policy, a holdover from the Jiang Zemin administration. Under the new policy, on the one hand, the PRC government continued a no-contact policy towards Chen Shui-bian. It maintained its military build-up against Taiwan, and pursued a vigorous policy of isolating Taiwan diplomatically. In March 2005, the Anti-Secession Law was passed by the National People's Congress, formalizing "non-peaceful means" as an option of response to a formal declaration of independence in Taiwan.

On the other hand, the PRC administration pursued contact with apolitical, or politically non-independence leaning, groups in Taiwan. In his May 17 Statement in 2004, Hu Jintao made friendly overtures to Taiwan on resuming negotiations for the "Three Links", reducing misunderstandings, and increasing consultation. However, the Anti-Secession Law was passed in 2005, which was not well received in Taiwan. The CCP increased contacts on a party-to-party basis with the KMT, then the opposition party in Taiwan, due to their support for the One China principle. The increased contacts culminated in the 2005 Pan-Blue visits to China, including a meeting between Hu and then-KMT chairman Lien Chan in April 2005.[55][56] It was the first meeting between the leaders of the two parties since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949.[57][58][59]

Inauguration of Ma Ying-jeou

On 22 March 2008, Ma Ying-jeou of the KMT won the presidential election in Taiwan. The KMT also won a large majority in the Legislature.[60]

There followed a series of meetings between the two sides. On 12 April 2008, Hu Jintao held a meeting with ROC's then vice-president elect Vincent Siew as chairman of the Cross-Straits Common Market Foundation during the Boao Forum for Asia. On 28 May 2008, Hu met with former KMT chairman Wu Po-hsiung, the first meeting between the heads of the CCP and the KMT as ruling parties. During this meeting, Hu and Wu agreed that both sides should recommence semi-official dialogue under the 1992 Consensus. Wu committed the KMT against Taiwanese independence, but also stressed that a "Taiwan identity" did not equate to "Taiwanese independence". Hu committed his government to addressing the concerns of the Taiwanese people in regard to security, dignity, and "international living space", with a priority given to discussing Taiwan's wish to participate in the World Health Organization.

Both Hu and his new counterpart, Ma Ying-jeou, considered the 1992 Consensus to be the basis for negotiations between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait. On 26 March 2008, Hu Jintao held a telephone talk with the US President George W. Bush, in which he explained that the "1992 Consensus" shows that "both sides recognize there is only one China, but agree to differ on its definition".[61][62][63] The first priority for the SEF–ARATS meeting was to be opening of the "Three Links", especially direct flights between China and Taiwan.

These events suggest a policy by the two sides to rely on the deliberate ambiguity of the 1992 Consensus to avoid difficulties arising from asserting sovereignty. As Wu Po-hsiung put it during a press conference in his 2008 China visit, "we do not refer to the 'Republic of China' so long as the other side does not refer to the 'People's Republic of China'". Since the March 2008 elections in Taiwan, the PRC government has not mentioned the "One China policy" in any official announcements. The only exception has been one brief aberration in a press release by the Ministry of Commerce, which described Vincent Siew as agreeing to the "1992 consensus and the one China policy". Upon an immediate protest from Siew, the PRC retracted the press release and issued apologetic statements emphasizing that only press releases published by China's Xinhua News Agency represented the official PRC position. The official press release on this event did not mention the One China policy.[64]

ROC President Ma Ying-jeou has advocated that cross-strait relations should shift from "mutual non-recognition" to "mutual non-denial".[65]

Reopened dialogue

Dialogue through semi-official organizations (the SEF and the ARATS) reopened on 12 June 2008 on the basis of the 1992 Consensus, with the first meeting held in Beijing. Neither the PRC nor the ROC recognizes the other side as a legitimate entity, so the dialogue was in the name of contacts between the SEF and the ARATS instead of the two governments, though most participants were in fact officials in PRC or ROC governments. On 13 June, President of the ARATS, Chen Yunlin, and President of the SEF, Chiang Pin-kung, signed files agreeing that direct flights between the two sides would begin on 4 July,[66] and that Taiwan would allow entrance of up to 3,000 visitors from China daily.[67] The first direct flights took off on 15 December 2008.[68]

The financial relationship between the two areas improved on 1 May 2009 in a move described as "a major milestone" by The Times.[69] The ROC's financial regulator, the Financial Supervisory Commission, announced that Chinese investors would be permitted to invest in Taiwan's money markets for the first time since 1949.[69] Investors can apply to purchase Taiwan shares that do not exceed one tenth of the value of the firm's total shares.[69] The move came as part of a "step by step" movement designed to relax restrictions on Chinese investment. Taipei economist Liang Chi-yuan commented: "Taiwan's risk factor as a flash point has dropped significantly with its improved ties with Chinese. The Chinese would be hesitant about launching a war as their investment increases here."[69] China's biggest telecoms carrier, China Mobile, was the first company to avail of the new movement by spending US$529 million on buying 12 percent of Far EasTone, the third largest telecoms operator in Taiwan.[69]

President Ma has called repeatedly for the PRC to dismantle the missile batteries targeted on Taiwan's cities, without result.[70]

A report in 2010 from Taiwan's Ministry of National Defense said that China's charm offensive is only accommodating on issues that do not undermine China's claim to Taiwan and that the PRC would invade if Taiwan declared independence, developed weapons of mass destruction, or suffered from civil chaos.[71]

On the 100th anniversary of the Republic of China (Xinhai Revolution), President Ma called on the PRC to embrace Sun Yat-sen's call for freedom and democracy.[72]

In June 2013, China offered 31 new measures to improve Taiwan's economic integration with the mainland.[73]

In October 2013, in a hotel lobby on the sidelines of the APEC Indonesia 2013 meetings in Bali, Wang Yu-chi, Minister of the Mainland Affairs Council, spoke briefly with Zhang Zhijun, Minister of the Taiwan Affairs Office, each addressing the other by his official title. Both called for the establishment of a regular dialogue mechanism between their two agencies to facilitate cross-strait engagement. Zhang also invited Wang to visit China.[74][75]

The two ministers met in Nanjing on 11 February 2014, in the first official, high-level, government-to-government contact between the two sides since 1949. The meeting took place at Nanjing's Purple Palace.[76][77] Nanjing was the capital of the Republic of China during the period in which it actually ruled China.[78][79] During the meeting, Wang and Zhang agreed on establishing a direct and regular communication channel between the two sides for future engagement under the 1992 Consensus. They also agreed on finding a solution for health insurance coverage for Taiwanese students studying in mainland China, on pragmatically establishing SEF and ARATS offices in their respective territories, and on studying the feasibility of allowing visits to detained persons once these offices had been established. Before shaking hands, Wang addressed Zhang as "TAO Director Zhang Zhijun" and Zhang addressed Wang as "Minister Wang Yu-chi" without mentioning the name Mainland Affairs Council.[80] However, the Xinhua News Agency referred to Wang as the "Responsible Official of Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council" (Chinese: 台湾方面大陆委员会负责人; pinyin: Táiwān Fāngmiàn Dàlù Wěiyuánhuì Fùzérén)[81] in its Chinese-language news, and as "Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Chief" in its English-language news.[82] Zhang paid a retrospective visit to Taiwan between 25 and 28 June 2014, making him the highest CCP official to ever visit the country.[83]

Sunflower Student Movement

In 2014, the Sunflower Student Movement broke out. Citizens occupied the Taiwanese legislature for 23 days, protesting against the government's forcing through the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement. The protesters felt that the trade pact with China would leave Taiwan vulnerable to political pressure from Beijing.[84]

In September 2014, the General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, Xi Jinping, adopted a more uncompromising stance than his predecessors as he called for the "one country, two systems" model to be applied to Taiwan. It was noted in Taiwan that Beijing was no longer referring to the 1992 Consensus.[85]

On 7 November 2015, Xi and Ma met and shook hands in Singapore, marking the first meeting between leaders of the two sides since the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949.[86][87] They met within their capacity as Leader of Mainland China and Leader of Taiwan respectively.

On 30 December 2015, a hotline connecting the head of the Mainland Affairs Council and the head of the Taiwan Affairs Office was established.[88] The first conversation via the hotline between the two heads took place on 5 February 2016.[89]

In March 2016, former ROC Justice Minister Luo Ying-shay embarked on a 5-day historic visit to mainland China, making her the first Minister of the Government of the Republic of China to visit the mainland after the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949.[90]

Inauguration of Tsai Ing-wen

.jpg.webp)

In the 2016 Taiwan general elections, Tsai Ing-wen and the DPP captured landslide victories.[91] Tsai initially pursued a similar strategy as Chen Shui-bian, but after winning the election she received a similarly frosty reception from the PRC.[92][93] Beijing has expressed its dissatisfaction with Tsai's refusal to accept the 1992 Consensus.[94]

On 1 June 2016, it was confirmed that former President Ma Ying-jeou would visit Hong Kong on 15 June to attend and deliver speech on Cross-Strait relations and East Asia at the 2016 Award for Editorial Excellence dinner at Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre.[95] The Tsai Ing-wen administration blocked Ma from traveling to Hong Kong,[96] and he gave prepared remarks via teleconference instead.[97]

In September 2016, eight magistrates and mayors from Taiwan visited Beijing, which were Hsu Yao-chang (Magistrate of Miaoli County), Chiu Ching-chun (Magistrate of Hsinchu County), Liu Cheng-ying (Magistrate of Lienchiang County), Yeh Hui-ching (Deputy Mayor of New Taipei City), Chen Chin-hu (Deputy Magistrate of Taitung County), Lin Ming-chen (Magistrate of Nantou County), Fu Kun-chi (Magistrate of Hualien County) and Wu Cheng-tien (Deputy Magistrate of Kinmen County). Their visit was aimed to reset and restart cross-strait relations after President Tsai Ing-wen took office on 20 May 2016. The eight local leaders reiterated their support of One-China policy under the 1992 Consensus. They met with Taiwan Affairs Office Head, Zhang Zhijun, and Chairperson of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, Yu Zhengsheng.[98][99][100]

In October 2017, Tsai Ing-wen expressed hopes that both sides would restart their cross-strait relations after the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, and argued that new practices and guidelines governing mutual interaction should be examined.[101] Regarding the old practices, Tsai stated that "If we keep sticking to these past practices and ways of thinking, it will probably be very hard for us to deal with the volatile regional situations in Asia".[102] Relations with the Mainland had stalled since Tsai took office in 2016.[103]

In his opening speech at the 19th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, CCP General Secretary Xi Jinping emphasized the PRC's sovereignty over Taiwan, stating that "We have sufficient abilities to thwart any form of Taiwan independence attempts."[104] At the same time, he offered the chance for open talks and "unobstructed exchanges" with Taiwan as long as the government moved to accept the 1992 Consensus.[104][105] His speech received a tepid response from Taiwanese observers, who argued that it did not signal any significant changes in Beijing's Taiwan policy, and showed "no significant goodwill, nor major malice."[106][107]

Beginning in the mid-to-late 2010s, Beijing has significantly restricted the number of Chinese tour groups allowed to visit Taiwan in order to place pressure upon President Tsai Ing-wen. Apart from Taiwan, the Holy See and Palau have also been pressured to recognize the PRC over the ROC.[108]

In 2018, The Diplomat reported that the PRC conducts hybrid warfare against the ROC.[109] ROC political leaders, including President Tsai and Premier William Lai, as well as international media outlets, have repeatedly accused the PRC of spreading fake news via social media to create divisions in Taiwanese society, influence voters and support candidates more sympathetic to Beijing ahead of the 2018 Taiwanese local elections.[110][111][112][113] Researchers have argued that the PRC government is allowing misinformation about the COVID-19 pandemic to flow into Taiwan.[114]

In 2019, Tsai Ing-wen explained the Taiwan government's position on a speech delivered by Xi Jinping commemorating the 40th anniversary of the so-called "Message to Compatriots in Taiwan." Tsai emphasized that the ROC has never accepted the 1992 Consensus.[115] Tsai stated that there's no need to talk about the 1992 Consensus anymore, because this term has already been defined by Beijing as "one country, two systems."[116] Tsai, who supported the 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, pledged that as long as she is Taiwan's president, she will never accept the "one country, two systems."[117]

In January 2020, Tsai Ing-wen argued that Taiwan already was an independent country called the "Republic of China (Taiwan)", further arguing that the mainland Chinese authorities had to recognize that situation.[118] Reuters reports that somewhere in 2020, the Taiwanese public turned further against mainland China, due to fallout from the Hong Kong protests and also due to the PRC's continued determination to keep the ROC out of the World Health Organization despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

The opposition KMT also appeared to distance itself from the Chinese mainland in 2020, stating it would review its unpopular advocacy of closer ties with the PRC.[119] In March 2021, KMT chairman Johnny Chiang rejected "one country, two systems" as a feasible model for Taiwan, citing Beijing's response to protests in Hong Kong as well as the value that Taiwanese place in political freedoms.[120]

The Hong Kong Economic, Trade and Cultural Office in Taiwan suspended its operation indefinitely on 18 May 2021, followed by the Macau Economic and Cultural Office starting 19 June 2021.[121]

In July 2021, the ROC's presidential office extended its condolences and sympathy to those affected by historic flooding in Zhengzhou in mainland China. In addition, Taiwanese companies and individuals made donations of money and supplies to help those affected.[122] The PRC indirectly thanked President Tsai for expressing concern, as well as offering thanks to companies and individuals who made contributions to relief efforts.[123]

In October 2021, the PRC denounced a speech by Tsai during commemorations for the National Day of the Republic of China. The PRC said that Tsai's speech "incited confrontation and distorted facts", and added that seeking Taiwanese independence was closing doors to dialogue.[124] Tsai responded by saying that the ROC would not be forced to "bow" down to mainland Chinese pressure, and said that the ROC would keep bolstering its defenses.[125]

In October 2021, Victor Gao, who served as an interpreter for former PRC paramount leader Deng Xiaoping, called for ethnic cleansing of any Taiwanese with Japanese heritage if the PRC were to take over the Taiwan Area in an interview.[126] Later in October a tweet from the Global Times called for a "final solution to the Taiwan question" which was condemned by German politician Frank Müller-Rosentritt for its similarity to the Nazis' "Final Solution to the Jewish question" which culminated in the Holocaust.[127]

In a biennial report released in November 2021, Taiwan's Ministry of Defense warned that the PRC had obtained the capacity to surround and blockade the island's harbors, airports, and outbound flight routes.[128]

On 10 June 2022, China's Defence Minister Wei Fenghe warned the United States that "if anyone dares to split Taiwan from China, the Chinese army will definitely not hesitate to start a war no matter the cost."[129] Wei further stated that the PLA "would have no choice but to fight … and crush any attempt of Taiwanese independence, safeguarding national sovereignty and territorial integrity."[130]

Following a ban on the importation of pineapples from Taiwan and wax apples in 2021, the Chinese government banned the import of grouper fish in June 2022, claiming they had found banned chemicals and excessive levels of other substances.[131][132]

2022 military exercises

On 2 August 2022, U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi visited Taiwan. China perceived her visit as a violation of its sovereign rights on Taiwan, and the PLA announced it would conduct live-fire exercises in six zones surrounding Taiwan from 4 August to 7 August.[133][134] The live-fire drills were unprecedented in recent history[134] and took place in zones that surrounded the island's busiest territorial waters and airspace.[135][136] The military exercises involved the usage of live-fire ammunition, air assets, naval deployments, and ballistic missile launches by the PLA.[137] In response, Taiwan deployed ships and aircraft. No military conflict came of this, although it greatly increased tensions between the two countries. China announced an end to the exercises on 10 August, but also stated that regular "patrols" would be launched in the Taiwan Strait.[138][139]

On 10 August 2022, the PRC's Taiwan Affairs Office and the State Council Information Office jointly published the first white paper about Taiwan's status since 2000 called "The Taiwan Question and China's Reunification in the New Era". In it, the PRC urged again for Taiwan to unify under the "one country, two systems" formula. Notably, the white paper did not contain a previous line stating that no troops would be sent to Taiwan after unification. In response, Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council said the white paper was "wishful thinking and disregarding facts".[140]

2023 military exercises

Another set of military exercises began on 8 April 2023, after president Tsai visited U.S. Speaker Kevin McCarthy in California.[141][142][143] Beijing called this operation the "Joint Sword". Taiwan reportedly spotted 70 aircraft and 11 ships from China. On the first day of the military exercises, one of the Chinese vessels discharged a shot while sailing near Pingtan Island – the nearest point between China and Taiwan.[144]

Interpretation of the relations by sitting leaders

Presidents Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo have steadily maintained that there is only one China, the sole representative of which was the ROC, and that the PRC government was illegitimate, while PRC leaders have maintained the converse that the PRC was the sole representative of China. In 1979, Deng Xiaoping proposed a model for the incorporation of Taiwan into the People's Republic of China which involved a high degree of autonomy within the Chinese state, similar to the model proposed to Hong Kong which would eventually become one country, two systems. On 26 June 1983, Deng proposed a meeting between the Kuomintang and the Chinese Communist Party as equal political parties and on 22 February, he officially proposed the "one country, two systems" model. In September 1990, under the presidency of Lee Teng-hui, the National Unification Council was established in Taiwan and in January 1991, the Mainland Affairs Council was established; in March 1991, the "Guidelines for National Unification" were adopted and on 30 April 1991, the period of mobilization for the suppression of Communist rebellion was terminated. Thereafter, the two sides conducted several rounds of negotiations through the informal Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) and Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS).[145]

On 22 May 1995, the United States granted Lee Teng-hui a visit to his alma mater, Cornell University, which resulted in the suspension of cross-strait exchanges by China, as well as the subsequent Third Taiwan Strait Crisis. Lee was labelled as a "traitor" attempting to "split China" by the PRC.[146][147] In an interview on 9 July 1999, President Lee Teng-hui defined the relations between Taiwan and mainland China as "between two countries (國家), at least special relations between two countries," and that there was no need for the Republic of China to declare independence since it had been independent since 1912 (the founding date of the Republic of China), thereby identifying the Taiwanese state with the Republic of China. Later, the MAC published an English translation of Lee's remarks referring instead to "two states of one nation," later changed on 22 July to "special state-to-state relations." In response, China denounced the theory and demanded retractions. Lee began to backpedal from his earlier marks, emphasizing the 1992 Consensus, whereby representatives from the two sides agreed that there was only one China, of which Taiwan was a part. However, the ROC maintained that the two sides agreed to disagree about which government represented China, whereas the PRC maintains that the two sides agreed that the PRC was the sole representative of China.[148]

On 3 August 2002, president Chen Shui-bian defined the relationship as One Country on Each Side (namely, that China and Taiwan are two different countries). The PRC subsequently cut off official contact with the ROC government.[149]

The ROC position under President Ma Ying-jeou backpedalled to a weaker version of Lee Teng-hui's position. On 2 September 2008, former ROC President Ma Ying-Jeou was interviewed by the Mexico-based newspaper El Sol de México and he was asked about his views on the subject of 'two Chinas' and if there is a solution for the sovereignty issues between the two. Ma replied that the relations are neither between two Chinas nor two states. It is a special relationship. Further, he stated that the sovereignty issues between the two cannot be resolved at present, but he quoted the '1992 Consensus' as a temporary measure until a solution becomes available.[150] Former spokesman for the ROC Presidential Office, Wang Yu-chi, later elaborated the President's statement and said that the relations are between two regions of one country, based on the ROC Constitutional position, the Statute Governing the Relations Between the Peoples of the Taiwan Area and Mainland Area and the '1992 Consensus'.[151] On 7 October 2008, Ma Ying-jeou was interviewed by a Japan-based magazine "World". He said that laws relating to international relations cannot be applied regarding the relations between Taiwan and the mainland, as they are parts of a state.[152][153][154]

In her first inauguration speech in 2016, President Tsai Ing-wen acknowledged that the talks surrounding the 1992 Consensus took place without agreeing that a consensus was reached. She credited the talks with spurring 20 years of dialogue and exchange between the two sides. She hoped that exchanges would continue on the basis of these historical facts, as well as the existence of the Republic of China's constitutional system and the democratic will of the Taiwanese people.[155] In response, Beijing called Tsai's answer an "incomplete test paper" because Tsai did not agree to the content of the 1992 Consensus.[156] On 25 June 2016, Beijing suspended official cross-strait communications,[157] with any remaining cross-strait exchanges thereafter taking place through unofficial channels.[158]

In January 2019, Xi Jinping, General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party wrote an open letter to Taiwan proposing a "one country, two systems" formula for eventual unification. Tsai responded to Xi in a January 2019 speech by stating that Taiwan rejects "one country, two systems", and that because Beijing equates it with the 1992 Consensus, Taiwan also rejects the latter.[159] Tsai again rejected one country, two systems explicitly in her second inauguration speech, and reaffirmed her previous stance that cross-strait exchanges be held on the basis of parity between the two sides. She affirmed the DPP's position that Taiwan, also known as the Republic of China, was already an independent country, and that Beijing must accept this reality.[160] She further remarked that cross-strait relations had reached a "historical turning point."[161]

On 5 March 2022, Chinese Premier Li Keqiang committed to promoting peaceful growth and "reunification" in relations with Taiwan, and stated his government resolutely rejects any separatist actions or foreign intervention, bringing a sharp rebuke from Taipei.[162]

Semi-official relations

Inter-government

Semi-governmental contact is maintained through the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) and the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS). Negotiations between the two organizations resumed on 11 June 2008.[163]

Although formally privately constituted bodies, the SEF and the ARATS are both directly led by the Executive Government of each side: the SEF by the Mainland Affairs Council of the ROC's Executive Yuan, and the ARATS by the Taiwan Affairs Office of the PRC's State Council. The heads of the two bodies, Lin Join-sane and Chen Deming, are both full-time appointees and do not hold other government positions. However, both are senior members of their respective political parties (Kuomintang and Chinese Communist Party respectively), and both have previously served as senior members of their respective governments. Their deputies, who in practice are responsible for the substantive negotiations, are concurrently senior members of their respective governments. For the June 2008 negotiations, the main negotiators, who are deputy heads of the SEF and the ARATS respectively, are concurrently deputy heads of the Mainland Affairs Council and the Taiwan Affairs Office respectively.

To date, the 'most official' representative offices between the two sides are the PRC's Cross-Strait Tourism Exchange Association (CSTEA) in Taiwan, established on 7 May 2010, and ROC's Taiwan Strait Tourism Association (TSTA) in China, established on 4 May 2010. However, the duties of these offices are limited only to tourism-related affairs so far.

Inter-party

The Kuomintang (former ruling party of Taiwan) and the Chinese Communist Party, maintain regular dialogue via the KMT–CCP Forum. This has been called a "second rail" in Taiwan and helps to maintain political understanding and aims for political consensus between the two parties.

Inter-city

The Shanghai-Taipei City Forum is an annual forum between the cities of Shanghai and Taipei. Launched in 2010 by then-Taipei Mayor Hau Lung-pin to promote city-to-city exchanges, it led to Shanghai's participation in the Taipei International Flora Exposition end of that year.[164] Both Taipei and Shanghai are the first two cities across the Taiwan Strait that carries out exchanges. In 2015, the newly elected Taipei Mayor Ko Wen-je attended the forum. He was addressed as Mayor Ko of Taipei by Shanghai Mayor Yang Xiong.[165]

Non-governmental

The third mode of contact is through private bodies accredited by the respective governments to negotiate technical and operational aspects of issues between the two sides. Called the "Macau mode", this avenue of contact was maintained even through the years of the Chen Shui-bian administration. For example, on the issue of opening Taiwan to Chinese tourists, the accredited bodies were tourism industry representative bodies from both sides.

Informal relations

The Three Links

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Regular weekend direct, cross-strait charter flights between mainland China and Taiwan resumed on 4 July 2008 for the first time since 1950. Liu Shaoyong, China Southern Airlines chair, piloted the first flight from Guangzhou to Taipei. Simultaneously, a Taiwan-based China Airlines flight flew to Shanghai. As of 2015, 61 mainland Chinese cities are connected with eight airports in Taiwan. The flights operate every day, totaling 890 round-trip flights across the Taiwan Strait per week.[167] Previously, regular passengers (other than festive or emergency charters) had to make a time-consuming stopover at a third destination, usually Hong Kong.[168][169]

Taiwan residents cannot use the Republic of China passport to travel to mainland China, and mainland China residents cannot use the People's Republic of China passport to travel to Taiwan, as neither the ROC nor the PRC considers this international travel. The PRC government requires Taiwan residents to hold a Mainland Travel Permit for Taiwan Residents when entering mainland China, whereas the ROC government requires mainland Chinese residents to hold the Exit and Entry Permit for the Taiwan Area of the Republic of China to enter the Taiwan Area.

Economy

.jpg.webp)

In 2021, the value of cross-strait trade stood at $328.3 billion.[170] Much of Taiwanese-owned manufacturing, particularly in the electronics sector and the apparel sector, occurs in the PRC.[171]: 11

In 2011, 2% of exports from mainland China went to Taiwan while 40% of exports from Taiwan went to mainland China and Hong Kong.[172] Since 2016, Taiwan has tried to reduce its economic reliance on mainland China through its New Southbound Policy - in 2022 Taiwan's total investments in the countries targeted by the policy outstripped investments in China for the first time.[173]

In 2015, 58% of Taiwanese working outside Taiwan worked in mainland China, with a total number of 420,000 people.[174] In 2021, the number fell to 163,000, accounting for 51.1 percent of the 319,000 Taiwanese who worked overseas.[175]

Since the governments on both sides of the strait do not recognize the other side's legitimacy, there is a lack of legal protection for cross-strait economic exchanges. The Economic Cooperation Framework Agreement (ECFA) was viewed as providing legal protection for investments.[176] In 2014, the Sunflower Student Movement effectively halted the Cross-Strait Service Trade Agreement (CSSTA).

Cultural, educational, religious, and sporting exchanges

The National Palace Museum in Taipei and the Palace Museum in Beijing have collaborated on exhibitions. Scholars and academics frequently visit institutions on the other side. Books published on each side are regularly re-published in the other side, though restrictions on direct imports and the different writing systems between the two sides somewhat impede the exchange of books and ideas.

Students of Taiwanese origin receive special concessions in the National Higher Education Entrance Examination in mainland China. There are regular programs for school students from each side to visit the other. In 2019, there were 30,000 mainland Chinese and Hong Kong students studying in Taiwan.[177] There were also more than 7,000 Taiwanese students studying in Hong Kong that same year.[178]

Religious exchange has become frequent. Frequent interactions occur between worshipers of Matsu, and also between Buddhists.

The Chinese football team Changchun Yatai F.C. chose Taiwan as the first stop of their 2015 winter training session, which is the first Chinese professional football team's arrival in Taiwan, and they were supposed to have an exhibition against Tatung F.C., which, however, wasn't successfully held, under unknown circumstances.

Humanitarian actions

Both sides have provided humanitarian aid to each other on several occasions. Following the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, an expert search and rescue team was sent from Taiwan to help rescue survivors in Sichuan. Shipments of aid material were also provided under the coordination of the Red Cross Society of the Republic of China and charities such as Tzu Chi.[179]

Public opinion

Taiwan

According to an opinion poll released by the Mainland Affairs Council (MAC) taken after the second 2008 meeting, 71.79% of the Taiwanese public supported continuing negotiations and solving issues between the two sides through the semi-official organizations, SEF and ARATS, 18.74% of the Taiwanese public did not support this, while 9.47% of the Taiwanese public did not have an opinion.[180]

In 2015, a poll conducted by the Taiwan Braintrust showed that about 90 percent of the population would identify themselves as Taiwanese rather than Chinese if they were to choose between the two. Also, 31.2 percent of respondents said they support independence for Taiwan, while 56.2 percent would prefer to maintain the status quo and 7.9 percent support unification with China.[181]

In 2016, a poll by the Taiwan Public Opinion Foundation showed that 51% approved and 40% disapproved of President Tsai Ing-wen's cross-strait policy. In 2017, a similar poll showed that 36% approved and 52% disapproved.[183] In 2018, 31% were satisfied while 59% were dissatisfied.[184]

Taiwanese polls have consistently shown rejection of the notion of "one China" and support for the fate of Taiwan to be decided solely by the Taiwanese. A June 2017 poll found that 70% of Taiwanese reject the idea of "one China".[185] In November 2017, a MAC poll showed that 85% of respondents believed that Taiwan's future should be decided only by the people of Taiwan, while 74% wanted China to respect the sovereignty of the Republic of China (Taiwan).[186] In January 2019, a MAC poll showed that 75% of Taiwanese rejected Beijing's view that the 1992 Consensus meant the "One China principle" under the framework of "one country, two systems". Further, 89% felt that the future of Taiwan should be decided by only the people of Taiwan.[187]

In 2020, an annual poll conducted by Academia Sinica showed that 73% of Taiwanese felt that China was "not a friend" of Taiwan, an increase of 15% from the previous year.[188] An annual poll run by National Chengchi University found that a record 67% of respondents identified as Taiwanese only, versus 27.5% who identified as both Chinese and Taiwanese and 2.4% who identified as Chinese only. The same poll showed that 52.3% of respondents favored postponing a decision or maintaining the status quo indefinitely, 35.1% of respondents favored eventual or immediate independence, and 5.8% favored eventual or immediate unification.[189]

On 12 November 2020, another MAC poll was released showing Taiwanese thinking on a set of topics. 90% of Taiwanese oppose China's military aggression against Taiwan. 80% believe maintaining cross-strait peace is the responsibility of both sides and not just Taiwan. 76% reject the "one country, two systems" approach proposed by Beijing. 86% believe only Taiwanese have the right to choose the path of self-determination for Taiwan.[190]

China

In January 2016, the leader of the pro-independence DPP, Tsai Ing-wen, was elected to the presidency of the Republic of China.[191] On 20 January, thousands of mainland Chinese internet users, primarily from the forum "Li Yi Tieba" (李毅貼吧), bypassed the Great Firewall of China to flood with messages and stickers the Facebook pages of the president-elect, Taiwanese news agencies Apple Daily and SET News, and other individuals to protest the idea of Taiwanese independence.[192][193][194]

Military build-up

Taiwan has more than 170,000 air raid shelters which would shelter much of the civilian population in the event of Chinese air or missile attack.[195]

In 2011, U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said that the United States would reduce arms sales to Taiwan if tensions were eased,[196] but that this was not a change in American policy.[197] In 2012, Commander Willard of the U.S. Pacific Command said that there was a reduced possibility of a cross-strait conflict accompanying greater interaction, though there were no reductions in military spending on either side.[198]

Beginning in 2016, China embarked on a massive military build-up.[199] In 2017, under the Trump administration, the U.S. began increasing military exchanges with Taiwan and passed two bills to allow high-level visits between government officials.[200][201] U.S. military vessels passed through the strait at a far greater rate than during President Barack Obama's two terms.[202]

In 2020, German Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer warned China not to pursue military action against Taiwan, saying that such a decision would be seen as a "major failure of statecraft" and it "would produce only losers".[203] The Deputy Director-General of Taiwan's National Security Bureau, Chen Wen-fan, stated in 2020 that Xi Jinping intends to solve the "Taiwan Problem" by 2049.[204] Japan is increasingly concerned with China's aggression as Taiwan was mentioned in a joint statement by Japanese Prime Minister Suga and President Joe Biden in April 2021.[205]

In 2022, U.S. Pacific Command described the situation of Cross-Straits relations as being dire, as China was amassing the largest build-up of military personnel and assets seen since the Second World War.[206][207] In October 2022, Admiral Mike Gilday, Chief of Naval Operations of the U.S. Navy, warned that the American military must be prepared for the possibility of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan before 2024.[208]

Following the August 2022 visit to Taiwan of Nancy Pelosi, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, the China Power Project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies polled 64 leading experts on the PRC, Taiwan, and cross-Strait relations, including 28 former high-level U.S. government (USG) officials from both Democrat and Republican administrations, as well as 23 former USG policy and intelligence analysts and 13 top experts from academia and think tanks.[209] Responses were collected from 10 August to 8 September 2022. The CSIS summarized the responses of the experts as follows: 1) China is determined to unify with Taiwan, but Beijing does not have a coherent strategy. 2) China is willing to wait to unify with Taiwan, and the August 2022 exercises are not an indicator of accelerated PRC timelines. 3) Xi Jinping feels there are still avenues to peaceful unification. 4) The potential for a military crisis or conflict in the Taiwan Strait is very real. 5) China would immediately invade if Taiwan declared independence. 6) China assumes that the United States would intervene in the event of a conflict with Taiwan.

See also

References

- Gold, Thomas B. (March 1987). "The Status Quo is Not Static: Mainland-Taiwan Relations". Asian Survey. 27 (3): 300–315. doi:10.2307/2644806. JSTOR 2644806.

- Blanchard, Ben; Lee, Yimou (3 January 2020). "Factbox: Key facts on Taiwan-China relations ahead of Taiwan elections". Reuters. Archived from the original on 6 April 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Green, Leslie C. (1993). The Contemporary Law of Armed Conflict. p. 79. ISBN 9780719035401. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- Lee, I-chia (12 March 2020). "Virus Outbreak: Flights bring 361 Taiwanese home". Taipei Times. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Zhang, Qiyun. (1959) An outline history of Taiwan. Taipei: China Culture Publishing Foundation

- Sanchze-Mazas (ed.) (2008) Past human migrations in East Asia : matching archaeology, linguistics and genetics. New York: Routledge.

- Brown, Melissa J. (2004) Is Taiwan Chinese? : the impact of culture, power, and migration on changing identities. Berkeley: University of California Press

- Lian, Heng (1920). 臺灣通史 [The General History of Taiwan] (in Chinese). OCLC 123362609.

- Teng, Emma J. (23 May 2019). "Taiwan and Modern China". Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- Morris, Andrew (2002). "The Taiwan Republic of 1895 and the Failure of the Qing Modernizing Project". In Stephane Corcuff (ed.). Memories of the Future: National Identity issues and the Search for a New Taiwan. New York: M.E. Sharpe. pp. 4–18. ISBN 978-0-7656-0791-1.

- Whitman, Alden. "The Life of Chiang Kai-shek: A Leader Who Was Thrust Aside by Revolution". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 February 2001. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang Tsang. The Cold War's Odd Couple: The Unintended Partnership Between the Republic of China and the UK, 1950–1958. [2006] (2006). I.B. Tauris. ISBN 1-85043-842-0. p 155, p 115-120, p 139-145

- Qi, Bangyuan. Wang, Dewei. Wang, David Der-wei. [2003] (2003). The Last of the Whampoa Breed: Stories of the Chinese Diaspora. Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-13002-3. pg 2

- "戡亂暨臺海戰役" [Counter-insurgency Campaign and Battle of the Taiwan Strait] (in Chinese (Taiwan)). 國軍歷史文物館. Archived from the original on 28 December 2011. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- Zhang, Ben (2017). 1950年上海大轰炸 [1950 Shanghai Bombing] (in Chinese) (1st ed.). ISBN 9787552019704.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick. Fairbank, John K. Twitchett, Denis C. [1991] (1991). The Cambridge History of China. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24337-8. pg 820.

- Kaufman, Victor S. (2001). "Trouble in the Golden Triangle: The United States, Taiwan and the 93rd Nationalist Division". The China Quarterly. 166: 440–456. doi:10.1017/S0009443901000213. JSTOR 3451165.

- Bush, Richard C. [2005] (2005). Untying the Knot: Making Peace in the Taiwan Strait. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 0-8157-1288-X.

- Chen, Jian (1992). "China's Changing Aims during the Korean War, 1950–1951". The Journal of American-East Asian Relations. 1 (1): 8–41. JSTOR 23613365.

- Nam, Kwang Kyu (2020). "U.S. Strategy and Role in Cross-Strait Relations: Focusing on U.S.-Taiwan Relations". The Journal of East Asian Affairs. 33 (1): 155–176. JSTOR 45441015.

- "14,000 Who Chose Freedom". Taiwan Today. 1 January 1964. Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Chang, Cheng David (2011). To return home or "Return to Taiwan" : conflicts and survival in the "Voluntary Repatriation" of Chinese POWs in the Korean War (PhD). University of California, San Diego. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "The first anti-communist heroes". Taipei Times. 17 January 2016. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Zhao, Suisheng (2023). The dragon roars back : transformational leaders and dynamics of Chinese foreign policy. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-5036-3415-2. OCLC 1332788951.

- O'Shaughnessy, Hugh (24 November 2007). "Kinmen: The island that Chairman Mao couldn't capture". The Independent. Archived from the original on 16 August 2021. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- "Details of Chiang Kai-shek's attempts to recapture mainland to be made public". South China Morning Post. 22 April 2009. Archived from the original on 21 October 2019.

- Wang, Guangci (20 April 2009). "Project National Glory. Makung Naval Battle Defeat. Waking up from the dream of retaking the mainland". United Daily News (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 22 April 2009.

- "Taiwan President rejects 'peace treaty' with China to avoid compromising national sovereignty". Taiwan News. 20 February 2019. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- "The Defectors' Story". Taiwan Today. 1 July 1961. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- "Justin Lin faces arrests if he returns: MND". Taipei Times. 15 March 2012. Retrieved 23 July 2023.

- Cabestan, Jean-Pierre (2000). "The Relations Across the Taiwan Strait: Twenty Years of Development and Frustration". China Review: 105–134. JSTOR 23453363.

- "Hijacked Plane Will End 2 Chinas' 40-Year Silence : Taiwan to Negotiate on Aircraft". Los Angeles Times. 13 May 1986. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "Plane hijacked to China returns to Taiwan". UPI. 23 May 1986. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Ger, Yeong-kuang (2015). "Cross-Strait Relations and the Taiwan Relations Act". American Journal of Chinese Studies. 22: 235–252. JSTOR 44289169.

- "Cross-strait reunions celebrated". Taipei Times. 12 May 2007. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "国务院关于鼓励台湾同胞投资的规定". flk.npc.gov.cn (in Chinese). Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- "Provisions of the State Council of the People's Republic of China for Encouraging Taiwan Compatriots to Invest in the Mainland". www.lawinfochina.com. Archived from the original on 21 December 2022. Retrieved 22 December 2022.

- Chou, Hui-ching (7 December 2018). "How the '1992 Consensus' Colors Taiwan's Fate". Commonwealth Magazine. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Chiu, Hungdah (1994). "The Koo-Wang Talks and Intra-Chinese Relations". American Journal of Chinese Studies. 2 (2): 219–262. JSTOR 44288492.

- Jacobs, J. Bruce; Liu, I-hao Ben (2007). "Lee Teng-Hui and the Idea of 'Taiwan'". The China Quarterly. 190: 375–393. doi:10.1017/S0305741007001245. JSTOR 20192775.

- "Taiwan's Lee speaks at Cornell". UPI. 9 June 1995. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- Ming, Chu-cheng (1996). "Political Interactions Across the Taiwan Straits". China Review: 175–200. JSTOR 23453144.

- Porch, Douglas (1999). "The Taiwan Strait Crisis of 1996: Strategic Implications for the United States Navy". Naval War College Review. 52 (3): 15–48. JSTOR 44643008.

- Scobell, Andrew (2000). "Show of Force: Chinese Soldiers, Statesmen, and the 1995–1996 Taiwan Strait Crisis". Political Science Quarterly. 115 (2): 227–246. doi:10.2307/2657901. JSTOR 2657901.

- Cabestan, Jean-Pierre (1999). "Wang Daohan and Koo Chen-fu Meet Again: A Political Dialogue... of the Deaf?". China Perspectives. 21: 25–27. JSTOR 24051197.

- Hu, Weixing (2000). "'Two-state' Theory versus One-China Principle: Cross-strait Relations in 1999". China Review: 135–156. JSTOR 23453364.

- Sheng, Lijun (2001). "Chen Shui-bian and Cross-Strait Relations". Contemporary Southeast Asia. 23 (1): 122–148. JSTOR 25798531.

- "Su Chi admits the '1992 consensus' was made up". Taipei Times. 22 February 2006. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- Cheng, Allen T. (14 July 2000). "Did He Say 'One China'?". Asiaweek. Archived from the original on 30 July 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- Lin, Syaru Shirley (29 June 2016). Taiwan's China Dilemma. Stanford University Press. pp. 96–98. ISBN 978-0804799287.

- "Taiwan Lifts Restrictions on Investment in China". The New York Times. 8 November 2001. Retrieved 23 September 2023.

- "Taiwan – timeline". BBC News. 9 March 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- Wang, Vincient Wei-cheng (2002). "The Chen Shui-Bian Administrations MainlandPolicy: Toward a Modus Vivendi or ContinuedStalemate?". Politics Faculty Publications and Presentations: 115.

- "Mainland scrambles to help Taiwan airlines". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Sisci, Francesco (5 April 2005). "Strange cross-Taiwan Strait bedfellows". Asia Times. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- Zhong, Wu (29 March 2005). "KMT makes China return in historic trip to ease tensions". The Standard. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2008.

- Hong, Caroline (30 April 2005). "Lien, Hu share 'vision' for peace". Taipei Times. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "Taiwanese opposition leader in Beijing talks". The Guardian. Associated Press. 29 April 2005.

- Hong, Caroline (28 March 2005). "KMT delegation travels to China for historic visit". Taipei Times. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "Decisive victory for Ma Ying-jeou". Taipei Times. 23 March 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2013.

- "Chinese, U.S. presidents hold telephone talks on Taiwan, Tibet". Xinhuanet. 27 March 2008. Archived from the original on 29 March 2008. Retrieved 15 May 2008.

- "Chinese, U.S. presidents hold telephone talks on Taiwan, Tibet". Consulate-General of the People's Republic of China in Vancouver. 26 March 2008. Archived from the original on 2 January 2022.

- Hille, Kathrin (3 April 2008). "Hopes rise for Taiwan-China dialogue". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 6 January 2022.

According to a US account of the talks, Mr Hu said: It is China's consistent stand that the Chinese mainland and Taiwan should restore consultation and talks on the basis of 'the 1992 consensus', which sees both sides recognise there is only one China, but agree to differ on its definition.

- 胡锦涛会见萧万长 就两岸经济交流合作交换意见 [Hu Jintao meets Vincent Siew; they exchanged opinions on cross-strait economic exchange and co-operation] (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. 12 April 2008. Archived from the original on 21 April 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- "晤諾貝爾得主 馬再拋兩岸互不否認" [Meeting Nobel laureates, Ma again speaks of mutual non-denial]. Liberty Times (in Chinese). 19 April 2008. Archived from the original on 25 May 2008. Retrieved 2 June 2008.

- 海峡两岸包机会谈纪要(全文) [Cross-Strait charter flights neogitation memorandum (full text)] (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. 13 June 2008. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- 海峡两岸关于大陆居民赴台湾旅游协议(全文) [Cross-Strait agreement on mainland residents visiting Taiwan for tourism (full text)] (in Chinese). Xinhua News Agency. 13 June 2008. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- Yu, Sophie; Macartney, Jane (16 December 2008). "Direct flights between China and Taiwan mark new era of improved relations". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 25 May 2010. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Taiwan opens up to mainland Chinese investors". The Times. London. 1 May 2009. Archived from the original on 8 May 2009. Retrieved 4 May 2009.

- John Pike. "President Ma urges China to dismantle missiles targeting Taiwan". globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 23 June 2011.

- Kelven Huang and Maubo Chang, ROC Central News Agency China military budget rises sharply: defense ministry Archived 1 September 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Ho, Stephanie. "China Urges Unification at 100th Anniversary of Demise of Last Dynasty." Archived 11 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine VoA, 10 October 2011.

- "China unveils 31 measures to promote exchanges with Taiwan". focustaiwan.tw. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- "Taiwan, Chinese ministers meet in groundbreaking first". focustaiwan.tw. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013.

- Video on YouTube

- "MAC, TAO ministers to meet today". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- "MAC Minister Wang in historic meeting". Taipei Times. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016.

- "China and Taiwan Hold First Direct Talks Since '49". The New York Times. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "China-Taiwan talks pave way for leaders to meet". The Sydney Morning Herald. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014.

- "MAC Minister Wang in historic meeting". Taipei Times. 12 February 2014. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014.

- 国台办主任张志军与台湾方面大陆委员会负责人王郁琦举行正式会面_图片频道_新华网 [Taiwan Affairs Office chairman Zhang Zhijun and Taiwan's Mainland Affairs Council "responsible official" Wang Yu-chi hold an official meeting: pictures and video]. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- "Cross-Strait affairs chiefs hold first formal meeting – Xinhua – English.news.cn". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014.

- "First minister-level Chinese official heads to Taipei for talks". Japan Times. 25 June 2014. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 27 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2016.

- J. Michael Cole, The Diplomat. "Hundreds of Thousands Protest Against Trade Pact in Taiwan". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Chou Chih-chieh (15 October 2014), Beijing seems to have cast off the 1992 Consensus Archived 3 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine China Times

- Huang, Cary (5 November 2015). "Xi's a mister, so is Ma: China and Taiwan have an unusual solution for an old problem". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 12 November 2015.

- Chiao, Yuan-Ming (7 November 2015). "Cross-strait leaders meet after 66 years of separation". China Post. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- "Hotline established for cross-strait affairs chiefs". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- "China picks up hotline call". 6 February 2016. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- "Minister of justice heads to China on historic visit". 29 March 2016. Archived from the original on 7 April 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Tai, Ya-chen; Chen, Chun-hua; Huang, Frances (17 January 2016). "Turnout in presidential race lowest in history". Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 17 January 2016.

- Romberg, Alan D. (1 March 2016). "The "1992 Consensus"—Adapting to the Future?". Hoover Institution. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- "Tsai's inauguration speech 'incomplete test paper': Beijing". Taipei Times. 21 May 2016. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- Wong, Yeni; Wu, Ho-I; Wang, Kent (26 August 2016). "Tsai's Refusal to Affirm the 1992 Consensus Spells Trouble for Taiwan". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Former president Ma to visit Hong Kong - Focus Taiwan". Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- Ramzy, Austin (14 June 2016). "Taiwan Bars Ex-President From Visiting Hong Kong". New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- "Full text of former President Ma Ying-jeou's video speech at SOPA". Central News Agency. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- "Local gov't officials hold meeting with Beijing". Archived from the original on 23 September 2016.

- "Local government heads arrive in Beijing for talks – Taipei Times". 18 September 2016. Archived from the original on 19 September 2016.

- "Kuomintang News Network". Archived from the original on 24 September 2016.

- "President Tsai calls for new model for cross-strait ties | ChinaPost". ChinaPost. 3 October 2017. Archived from the original on 4 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Tsai renews call for new model on cross-strait ties – Taipei Times". taipeitimes.com. 4 October 2017. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 4 October 2017.

- "Relations with Beijing bedevil Taiwan's Tsai one year on". Nikkei Asia Review. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017.

- hermesauto (18 October 2017). "19th Party Congress: Any attempt to separate Taiwan from China will be thwarted". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- 习近平:我们有足够能力挫败"台独"分裂图谋_新改革时代. news.ifeng.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- 習近平維持和平統一基調 學者提醒反獨力道加大 – 政治 – 自由時報電子報. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- 十九大對台發言重要嗎? 人渣文本:不痛不癢,沒有新意 – 政治 – 自由時報電子報. 19 October 2017. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2017.

- "China bans tour groups to Vatican, Palau to isolate Taiwan – Taiwan News". 23 November 2017. Archived from the original on 27 November 2017. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- "China's Hybrid Warfare and Taiwan". The Diplomat. 13 January 2018. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "'Fake news' rattles Taiwan ahead of elections". Al-Jazeera. 23 November 2018. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Analysis: 'Fake news' fears grip Taiwan ahead of local polls". BBC Monitoring. 21 November 2018. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "Fake news: How China is interfering in Taiwanese democracy and what to do about it". Taiwan News. 23 November 2018. Archived from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "China's hybrid warfare against Taiwan". The Washington Post. 14 December 2018. Archived from the original on 14 October 2019. Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "With Odds Against It, Taiwan Keeps Coronavirus Corralled". NPR. 13 March 2020. Archived from the original on 21 March 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- "President Tsai issues statement on China's President Xi's "Message to Compatriots in Taiwan"". english.president.gov.tw. 2 January 2019.

- "Taiwan's President, Defying Xi Jinping, Calls Unification Offer "Impossible"". The New York Times. 5 January 2019. Archived from the original on 5 January 2019. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- "Tsai, Lai voice support for Hong Kong extradition bill protesters". Foucs Taiwan. 10 June 2019. Archived from the original on 1 July 2020. Retrieved 4 July 2023.

- "Tsai Ing-wen says China must 'face reality' of Taiwan's independence". TheGuardian.com. 15 January 2020. Archived from the original on 3 February 2020. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- "Taiwan opposition seeks distance from China after poll defeat". Reuters. 7 June 2020. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Blanchard, Ben; Lee, Yimou. "Taiwan opposition chief in no rush for China meeting". Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 11 March 2021.

- Cheung, Stanley; Yeh, Joseph (16 June 2021). "Macao office in Taipei suspends operation following HK office closure". Focus Taiwan. Archived from the original on 17 June 2021. Retrieved 17 June 2021.

- Tzu-ti, Huang (22 July 2021). "Taiwan president extends sympathy to China over devastating floods". www.taiwannews.com.tw. Taiwan News. Archived from the original on 22 July 2021. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- Blanchard, Ben (22 July 2021). "China thanks Taiwan president, indirectly, for concern over floods". www.reuters.com. Reuters. Retrieved 22 July 2021.

- "China denounces Taiwan president's speech". Reuters. 10 October 2021. Archived from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Blanchard, Ben; Lee, Yimou (10 October 2021). "Taiwan won't be forced to bow to China, president says". Reuters. Archived from the original on 12 April 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2021.

- Why China Won't Back Off Taiwan Archived 14 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Foreign Policy, 13 October 2021

- Haime, Jordyn. "Chinese state-run site proposes 'final solution to the Taiwan question'". www.jpost.com. The Jerusalem Post. Archived from the original on 30 June 2022. Retrieved 21 October 2021.

- Chung, Lawrence. "China can already cut Taiwan off by sea and by air, Taiwan's military says". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- "US blasts China's 'destabilising' military activity near Taiwan". France 24. 11 June 2022. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.

- "'Smash to smithereens': China threatens all-out war over Taiwan". Al-Jazeera. 10 June 2022. Archived from the original on 13 August 2022. Retrieved 13 August 2022.