Dracovenator

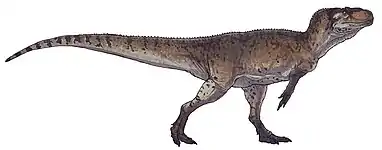

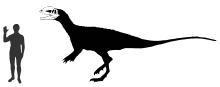

Dracovenator (/ˌdrækoʊvɛˈneɪtər/) is a genus of neotheropod dinosaur that lived approximately 201 to 199 million years ago during the early part of the Jurassic Period in what is now South Africa. Dracovenator was a medium-sized, moderately-built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore, that could grow up to an estimated 5.5–6.5 metres (18–21 ft) in length and 250 kilograms (550 lb) in body mass. Its type specimen was based on only a partial skull that was recovered.

| Dracovenator Temporal range: Early Jurassic, | |

|---|---|

| |

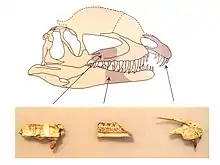

| Partial skull of Dracovenator regenti | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Neotheropoda |

| Genus: | †Dracovenator Yates, 2005 |

| Species: | †D. regenti |

| Binomial name | |

| †Dracovenator regenti Yates, 2005 | |

Discovery

The type material BP/1/5243 for Dracovenator was discovered at the "Upper Drumbo Farm" locality in the upper Elliot Formation which is part of the Stormberg Group in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. It was collected by James Kitching and Regent "Lucas" Huma in sandstone that was deposited during the Hettangian stage of the Jurassic period, approximately 201 to 199 million years ago. The paratype material BP/1/5278 (originally assigned to Syntarsus rhodesiensis) was discovered in 1981, also at the Elliot Formation in pinkish-maroon silty mudstone that was deposited in Hettangian sediments.[1] Both the holotype and paratype specimen were housed in the fossil collection of the Evolutionary Studies Institute, part of the School of Geosciences of the University of the Witwatersrand, in Johannesburg, South Africa. Unfortunately the cranial material house at the Evolutionary Studies Institute was lost and no new fossils of Dracovenator have currently been found.

The genus name is a contraction of the Latin words draco meaning "dragon", and venator meaning "hunter"; thus, "dragon hunter". "Draco" refers to its discovery in the foothills of Drakensberg, which is "Dragon’s Mountain" in the Dutch language. The specific name, regenti, was named in the honor of the late Regent ‘Lucas’ Huma, who was Professor Kitching’s field assistant. Dracovenator was described and named by Adam M. Yates in 2005 and the type species is Dracovenator regenti.

Description

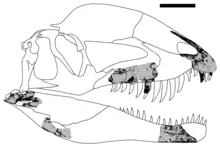

Dracovenator is estimated to have measured between 5.5 and 6.5 m (18 and 21 ft) in length and 250 kg (550 lb) in body mass.[2][3] The holotype specimen, BP/1/5243, consists of both premaxillae, a fragment of the maxilla, two dentary fragments, a partial surangular bone, a partial angular bone, a partial prearticular bone, an articular bone, and several teeth. Dracovenator has a kink in its upper jaws, between the maxilla and the premaxilla. The back end of the lower jaw features an array of lumps and bumps, a condition seen in Dilophosaurus, but to a much smaller extent. Munyikwa and Raath (1999) reassigned paratype BP/1/5278, which was originally assigned to Syntarsus rhodesiensis, to Dracovenator, a juvenile specimen which consists of bones from the front of the skull, teeth, and jaw bones.[1]

A diagnosis is a statement of the anatomical features of an organism (or group) that collectively distinguish it from all other organisms. Some, but not all, of the features in a diagnosis are also autapomorphies. An autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature that is unique to a given organism. According to Yates (2005) Dracovenator can be distinguished based on the following characteristics: the presence of a large bilobed fossa surrounding a large lateral premaxillary foramen that is connected to the alveolar margin by a deep narrow channel; a deep, oblique notch on the lateral surface of the articular bone, separating the retroarticular process from the posterior margin of the glenoid, a particularly well-developed dorsal, tab-like processes on the articular bone-the first on the medial side, just posterior to the opening of the chorda tympanic foramen and the second on the lateral side on the anterolateral margin of the fossa for the m. depressor mandibulae.[4]

Classification

Yates (2005) assigned Dracovenator to the clade Neotheropoda.[4] The first cladistic analysis found that this genus formed a clade with the basal theropods Dilophosaurus and Zupaysaurus. The skull of the type specimen, exhibits a mosaic of both ancestral and derived theropod characteristics. The following cladogram, based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Smith, Makovicky, Pol, Hammer, and Currie in 2007, outlines the relationships of Dracovenator and its close relatives:[5]

| Neotheropoda |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

The Upper Elliot Formation is thought to have been an ancient floodplain. Fossils of the prosauropod dinosaur Massospondylus and Plateosaurus have been recovered from the Upper Elliot Formation, which boasts the world's most diverse fauna of early Jurassic ornithischian dinosaurs, including Abrictosaurus, Fabrosaurus, Heterodontosaurus, and Lesothosaurus, among others. The Forest Sandstone Formation was the paleoenvironment of protosuchid crocodiles, sphenodonts, the dinosaur Massospondylus and indeterminate remains of a prosauropod. Dracovenator is thought to have preyed on the prosauropod dinosaurs in its paleoenvironment.

References

- Munyikwa and Raath, 1999. Further material of the ceratosaurian dinosaur Syntarsus from the Elliot Formation (Early Jurassic) of South Africa. Palaeontologia Africana. 35:55-59.

- Smith, N.D., Makovicky, P.J., Pol, D., Hammer, W.R., and Currie, P.J. (2007). "The Dinosaurs of the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Central Transantarctic Mountains: Phylogenetic Review and Synthesis". U.S. Geological Survey and The National Academies doi:10.3133/of2007-1047.srp003

- Paul, G. S. (2016). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs (2nd ed.). Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780691167664.

- A. M. Yates. 2005. A new theropod dinosaur from the Early Jurassic of South Africa and its implications for the early evolution of theropods. Palaeontologia Africana 41:105-122

- Smith, N.D., Makovicky, P.J., Pol, D., Hammer, W.R., and Currie, P.J. (2007). "The dinosaurs of the Early Jurassic Hanson Formation of the Central Transantarctic Mountains: Phylogenetic review and synthesis." In Cooper, A.K. and Raymond, C.R. et al. (eds.), Antarctica: A Keystone in a Changing World––Online Proceedings of the 10th ISAES, USGS Open-File Report 2007-1047, Short Research Paper 003, 5 p.

.jpg.webp)