Eannatum

Eannatum (Sumerian: 𒂍𒀭𒈾𒁺 É.AN.NA-tum2) was a Sumerian Ensi (ruler or king) of Lagash circa 2500–2400 BCE. He established one of the first verifiable empires in history, subduing Elam and destroying the city of Susa, and extending his domain over the rest of Sumer and Akkad.[1] One inscription found on a boulder states that Eannatum was his Sumerian name, while his "Tidnu" (Amorite) name was Lumma.

| Eannatum 𒂍𒀭𒈾𒁺 | |

|---|---|

| King of Lagash | |

Eannatum, King of Lagash, riding a war chariot (detail of the Stele of the Vultures). His name "Eannatum" (𒂍𒀭𒈾𒁺) is written vertically in two columns in front of his head. Louvre Museum. | |

| Reign | c. 2500 BC – 2400 BC |

| Predecessor | Akurgal |

| Successor | En-anna-tum I |

| Dynasty | 1st Dynasty of Lagash |

Conquest of Sumer

Eannatum, grandson of Ur-Nanshe and son of Akurgal, was a king of Lagash who conquered all of Sumer, including Ur, Nippur, Akshak (controlled by Zuzu), Larsa, and Uruk (controlled by Enshakushanna, who is on the King List).[1]

He entered into conflict with Umma, waging a war over the fertile plain of Gu-Edin.[1] He personally commanded an army to subjugate the city-state, and vanquished Ush, the ruler of Umma, finally making a boundary treaty with Enakalle, successor of Ush, as described in the Stele of the Vultures and in the Cone of Entemena:[2][1]

32–38

𒂍𒀭𒈾𒁺 𒉺𒋼𒋛 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠 𒉺𒄑𒉋𒂵 𒂗𒋼𒈨𒈾 𒉺𒋼𒋛 𒉢𒁓𒆷𒆠𒅗𒆤

e2-an-na-tum2 ensi2 lagaški pa-bil3-ga en-mete-na ensi2 lagaški-ka-ke4

"Eannatum, ruler of Lagash, uncle of Entemena, ruler of Lagash"

39–42

𒂗𒀉𒆗𒇷 𒉺𒋼𒋛 𒄑𒆵𒆠𒁕 𒆠 𒂊𒁕𒋩

en-a2-kal-le ensi2 ummaki-da ki e-da-sur

"fixed the border with Enakalle, ruler of Umma"

Extract from the Cone of Enmetena, Room 236 Reference AO 3004, Louvre Museum.[3][4]

Eannatum made Umma a tributary, where every person had to pay a certain amount of grain into the treasury of the goddess Nina and the god Ingurisa.[5][1]

Conquest outside Sumer

Eannatum expanded his influence beyond the boundaries of Sumer. He conquered parts of Elam, including the city Az off the coast of the modern Persian Gulf, allegedly smote Shubur, and, having repulsed Akshak, he claimed the title of "King of Kish" (which regained its independence after his death) and demanded tribute as far as Mari:[1]

"He (Eannatum) defeated Zuzu, the king of Akshak, from the Antasurra of Ningirsu up to Akshak and destroyed him."

"The king of Akshak ran back to his land."

"He defeated Kish, Akshak, and Mari from the Antasurra of Ningirsu."

"To Eannatum, the ruler of Lagash, Inanna gave the kingship of Kish in addition to ensi-ship of Lagash, because she loved him."— Inscriptions of Eannatum.[6]

Eannatum recorded his victories on a stone inscription:

Eannatum, the ensi of Lagash, who was granted might by Enlil, who constantly is nourished by Ninhursag with her milk, whose name Ningirsu had pronounced, who was chosen by Nanshe in her heart, the son of Akurgal, the ensi of Lagash, conquered the land of Elam, conquered Urua, conquered Umma, conquered Ur. At that time, he built a well made of baked bricks for Ningirsu, in his wide temple courtyard. Eananatum's god is Shulutula. Then did Ningirsu love Eannatum".

However, revolts often arose in parts of his empire. During Eannatum’s reign, many temples and palaces were built, especially in Lagash.[9] The city of Nina, probably a precursor of Niniveh, was rebuilt, with many canals and reservoirs being excavated.

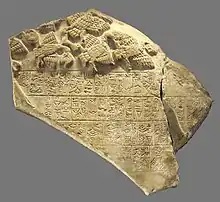

Stele of the Vultures

The so-called Stele of the Vultures, now in the Louvre, is a fragmented limestone stele found in Telloh, (ancient Girsu) Iraq, in 1881. The stele is reconstructed as having been 1.80 metres (5 ft 11 in) high and 1.30 metres (4 ft 3 in) wide and was set up ca. 2500–2400 BCE.[10] It was erected as a monument of the victory of Eannatum of Lagash over Ush, king of Umma, leading to a boundary treaty with his successor Enakalle of Umma.[11][5]

On it various incidents in the war are represented. In one register, the king (his name appears inscribed around his head) stands in front of his phalanx of heavily armoured soldiers, with a curved weapon in his right hand, formed of three bars of metal bound together by rings. In another register a figure, the king, his name again inscribed around his head, rides on his chariot in the thick of the battle, while his kilted followers, with helmets on their heads and lances in their hands, march behind him.[5]

On the other side of the stele is an image of Ninurta, a god of war, holding the captive Ummaites in a large net. This implies that Eannatum attributed his victory to Ninurta, and thus that he was in the god's protection (though some accounts say that he attributed his victory to Enlil, the patron deity of Lagash).[10][5]

The victory of Eannatum is mentioned in a fragmentary inscription on the stele, suggesting that after the loss of 3,600 soldiers on the field, Ush, king of Umma, was killed in a rebellion in his capital city of Umma: “[…] (Eanatum) defeated him. Its ( = Umma’s) 3600 corpses reached the base of heaven [...] raised (their) hands against him and killed him in Umma.”.[12]

.jpg.webp) Eannatum leading his troops in battle. Top: Eannatum leading a phalanx on foot. Bottom: Eannatum leading troops in a war charriot. Fragment of the Stele of the Vultures

Eannatum leading his troops in battle. Top: Eannatum leading a phalanx on foot. Bottom: Eannatum leading troops in a war charriot. Fragment of the Stele of the Vultures

Upper register of the "mythological" side

Upper register of the "mythological" side Detail of the "battle" fragment

Detail of the "battle" fragment

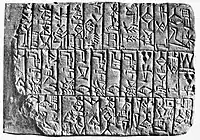

Other inscriptions

Inscribed brick of Eannatum, recording the sinking of a well in the forecourt of the Temple of Ningirsu in Lagash.[13]

Inscribed brick of Eannatum, recording the sinking of a well in the forecourt of the Temple of Ningirsu in Lagash.[13] Name of Enneatum on his Ningirsu inscription (top right corner).

Name of Enneatum on his Ningirsu inscription (top right corner)..jpg.webp) Eannatum inscription (British Museum)

Eannatum inscription (British Museum).jpg.webp)

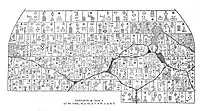

Foundation stone of Eannatum (transcription)

Foundation stone of Eannatum (transcription)

Eannatum King of Lagash presiding at funeral rites on the battlefield (20th century reconstitution)

Eannatum King of Lagash presiding at funeral rites on the battlefield (20th century reconstitution) Clay tablet mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash. From Iraq, c. 2470 BCE. Iraq Museum

Clay tablet mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash. From Iraq, c. 2470 BCE. Iraq Museum Fragment of a vessel mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash, from Iraq, c. 2470 BCE. Iraq Museum

Fragment of a vessel mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash, from Iraq, c. 2470 BCE. Iraq Museum Stone pebble mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash, from Iraq, c. 2470 BCE, Iraq Museum

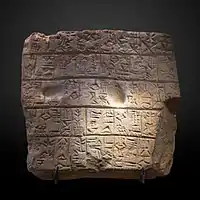

Stone pebble mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash, from Iraq, c. 2470 BCE, Iraq Museum Stone plaque or tablet mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash, from Iraq, c. 2470 BCE. Iraq Museum

Stone plaque or tablet mentioning the name of Eannatum, prince of Lagash, from Iraq, c. 2470 BCE. Iraq Museum%252C_ruler_of_Lagash%252C_2500-2400_BCE._Ancient_Orient_Museum%252C_Istanbul.jpg.webp) Detail. Cuneiform inscription on a limestone object from Girsu, Iraq, mentioning the name of Eannatum, Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

Detail. Cuneiform inscription on a limestone object from Girsu, Iraq, mentioning the name of Eannatum, Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

References

- Van De Mieroop, Marc (2004). A History of the Ancient Near East: Ca. 3000-323 BC. Wiley. pp. 50–51. ISBN 9780631225522.

- The Cities of Babylonia. Cambridge Ancient History. p. 28.

- "Cone of Enmetena, king of Lagash". 2020.

- "CDLI-Found Texts". cdli.ucla.edu. Retrieved 2018-03-12.

- Finegan, Jack (2019). Archaeological History Of The Ancient Middle East. Routledge. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-429-72638-5.

- MAEDA, TOHRU (1981). "KING OF KISH" IN PRE-SARGONIC SUMER. Orient: The Reports of the Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan, Volume 17. pp. 10 and 7.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6.

- "Louvre Museum Official Website". cartelen.louvre.fr.

- Maisels, Charles Keith (2003). The Emergence of Civilization: From Hunting and Gathering to Agriculture, Cities, and the State of the Near East. Routledge. p. 174. ISBN 978-1-134-86327-3.

- Kleiner, Fred S.; Mamiya, Christin J. (2006). Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective — Volume 1 (12th ed.). Belmont, California, USA: Thomson Wadsworth. pp. 22–23. ISBN 0-495-00479-0.

- The Cities of Babylonia. Cambridge Ancient History. p. 28.

- Sallaberger, Walther; Schrakamp, Ingo (2015). History & Philology (PDF). Walther Sallaberger & Ingo Schrakamp (eds), Brepols. p. 75. ISBN 978-2-503-53494-7.

- Transliteration and photograph: "CDLI-Archival View". cdli.ucla.edu.

- "Louvre Museum Official Website". cartelen.louvre.fr.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. p. 309, #10. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6.

- Kramer, Samuel Noah (2010). The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character. University of Chicago Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-226-45232-6.

- "Louvre Museum Official Website". cartelen.louvre.fr.