Equator

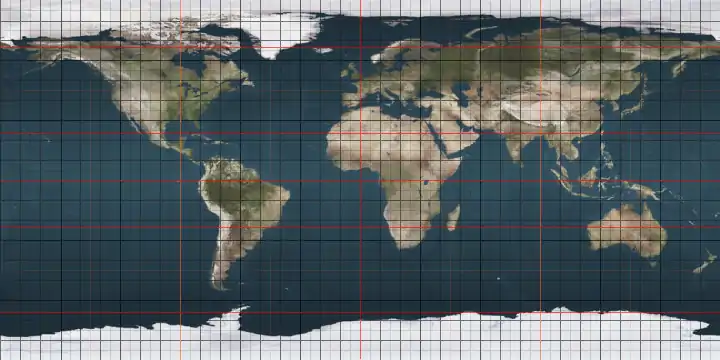

The equator is a circle of latitude that divides a spheroid, such as Earth, into the northern and southern hemispheres. On Earth, it is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, about 40,075 km (24,901 mi) in circumference, halfway between the North and South poles.[1] The term can also be used for any other celestial body that is roughly spherical.

.svg.png.webp)

In spatial (3D) geometry, as applied in astronomy, the equator of a rotating spheroid (such as a planet) is the parallel (circle of latitude) at which latitude is defined to be 0°. It is an imaginary line on the spheroid, equidistant from its poles, dividing it into northern and southern hemispheres. In other words, it is the intersection of the spheroid with the plane perpendicular to its axis of rotation and midway between its geographical poles.

On and near the equator (on Earth), noontime sunlight appears almost directly overhead (no more than about 23° from the zenith) every day, year-round. Consequently, the equator has a rather stable daytime temperature throughout the year. On the equinoxes (approximately March 20 and September 23) the subsolar point crosses Earth's equator at a shallow angle, sunlight shines perpendicular to Earth's axis of rotation, and all latitudes have nearly a 12-hour day and 12-hour night.[2]

Etymology

The name is derived from medieval Latin word aequator, in the phrase circulus aequator diei et noctis, meaning 'circle equalizing day and night', from the Latin word aequare 'make equal'.[3]

Overview

The latitude of the Earth's equator is, by definition, 0° (zero degrees) of arc. The equator is one of the five notable circles of latitude on Earth; the other four are the two polar circles (the Arctic Circle and the Antarctic Circle) and the two tropical circles (the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn). The equator is the only line of latitude which is also a great circle—meaning, one whose plane passes through the center of the globe. The plane of Earth's equator, when projected outwards to the celestial sphere, defines the celestial equator.

In the cycle of Earth's seasons, the equatorial plane runs through the Sun twice a year: on the equinoxes in March and September. To a person on Earth, the Sun appears to travel along the equator (or along the celestial equator) at these times.

Locations on the equator experience the shortest sunrises and sunsets because the Sun's daily path is nearly perpendicular to the horizon for most of the year. The length of daylight (sunrise to sunset) is almost constant throughout the year; it is about 14 minutes longer than nighttime due to atmospheric refraction and the fact that sunrise begins (or sunset ends) as the upper limb, not the center, of the Sun's disk contacts the horizon.

Earth bulges slightly at the equator; its average diameter is 12,742 km (7,918 mi), but the diameter at the equator is about 43 km (27 mi) greater than at the poles.[1]

Sites near the equator, such as the Guiana Space Centre in Kourou, French Guiana, are good locations for spaceports as they have the fastest rotational speed of any latitude, 460 m (1,509 ft)/sec. The added velocity reduces the fuel needed to launch spacecraft eastward (in the direction of Earth's rotation) to orbit, while simultaneously avoiding costly maneuvers to flatten inclination during missions such as the Apollo Moon landings.[4]

Geodesy

Precise location

The precise location of the equator is not truly fixed; the true equatorial plane is perpendicular to the Earth's rotation axis, which drifts about 9 metres (30 ft) during a year.

Geological samples show that the equator significantly changed positions between 48 and 12 million years ago, as sediment deposited by ocean thermal currents at the equator shifted. The deposits by thermal currents are determined by the axis of the Earth, which determines solar coverage of the Earth's surface. Changes in the Earth's axis can also be observed in the geographic layout of volcanic island chains, which are created by shifting hot spots under the Earth's crust as the axis and crust move.[5] This is consistent with the Indian tectonic plate colliding with the Eurasian tectonic plate, which is causing the Himalayan uplift.

Exact length

The International Association of Geodesy (IAG) and the International Astronomical Union (IAU) use an equatorial radius of 6,378.1366 km (3,963.1903 mi) (codified as the IAU 2009 value).[6] This equatorial radius is also in the 2003 and 2010 IERS Conventions.[7] It is also the equatorial radius used for the IERS 2003 ellipsoid. If it were really circular, the length of the equator would then be exactly 2π times the radius, namely 40,075.0142 km (24,901.4594 mi). The GRS 80 (Geodetic Reference System 1980) as approved and adopted by the IUGG at its Canberra, Australia meeting of 1979 has an equatorial radius of 6,378.137 km (3,963.191 mi). The WGS 84 (World Geodetic System 1984) which is a standard for use in cartography, geodesy, and satellite navigation including GPS, also has an equatorial radius of 6,378.137 km (3,963.191 mi). For both GRS 80 and WGS 84, this results in a length for the equator of 40,075.0167 km (24,901.4609 mi).

The geographical mile is defined as one arc-minute of the equator, so it has different values depending on which radius is assumed. For example, by WSG-84, the distance is 1,855.3248 metres (6,087.024 ft), while by IAU-2000, it is 1,855.3257 metres (6,087.027 ft). This is a difference of less than one millimetre (0.039 in) over the total distance (approximately 1.86 kilometres or 1.16 miles).

The earth is commonly modeled as a sphere flattened 0.336% along its axis. This makes the equator 0.16% longer than a meridian (a great circle passing through the two poles). The IUGG standard meridian is, to the nearest millimetre, 40,007.862917 kilometres (24,859.733480 mi), one arc-minute of which is 1,852.216 metres (6,076.82 ft), explaining the SI standardization of the nautical mile as 1,852 metres (6,076 ft), more than 3 metres (9.8 ft) less than the geographical mile.

The sea-level surface of the Earth (the geoid) is irregular, so the actual length of the equator is not so easy to determine. Aviation Week and Space Technology on 9 October 1961 reported that measurements using the Transit IV-A satellite had shown the equatorial diameter from longitude 11° West to 169° East to be 1,000 feet (305 m) greater than its diameter ninety degrees away.

Equatorial countries and territories

.jpg.webp)

The Equator passes through the land of 11 sovereign states. Indonesia is the country straddling the greatest length of the equatorial line across both land and sea. Starting at the prime meridian and heading eastwards, the Equator passes through:

The Equator also passes through the territorial seas of three countries: Maldives (south of Gaafu Dhaalu Atoll), Kiribati (south of Buariki Island), and the United States (south of Baker Island).

Despite its name, no part of Equatorial Guinea lies on the Equator. However, its island of Annobón is 155 km (96 mi) south of the Equator, and the rest of the country lies to the north. France, Norway (Bouvet Island), and the United Kingdom are the other three Northern Hemisphere-based countries which have territories in the Southern Hemisphere.

Equatorial seasons and climate

Diagram of the seasons, showing the situation at the December solstice. Regardless of the time of day (i.e. Earth's rotation on its axis), the North Pole will be dark, and the South Pole will be illuminated; see also polar night. In addition to the density of incident light, the dissipation of light in atmosphere is greater when it falls at a shallow angle.

Seasons result from the tilt of Earth's axis away from a line perpendicular to the plane of its revolution around the Sun. Throughout the year, the Northern and Southern hemispheres are alternately turned either toward or away from the Sun, depending on Earth's position in its orbit. The hemisphere turned toward the Sun receives more sunlight and is in summer, while the other hemisphere receives less sun and is in winter (see solstice).

At the equinoxes, Earth's axis is perpendicular to the Sun rather than tilted toward or away, meaning that day and night are both about 12 hours long across the whole of Earth.

Near the equator, this means the variation in the strength of solar radiation is different relative to the time of year than it is at higher latitudes: maximum solar radiation is received during the equinoxes, when a place at the equator is under the subsolar point at high noon, and the intermediate seasons of spring and autumn occur at higher latitudes; and the minimum occurs during both solstices, when either pole is tilted towards or away from the sun, resulting in either summer or winter in both hemispheres. This also results in a corresponding movement of the equator away from the subsolar point, which is then situated over or near the relevant tropic circle. Nevertheless, temperatures are high year-round due to the Earth's axial tilt of 23.5° not being enough to create a low minimum midday declination to sufficiently weaken the Sun's rays even during the solstices. High year-round temperatures extend to about 25° north or south of the equator, although the moderate seasonal temperature difference is defined by the opposing solstices (as it is at higher latitudes) near the poleward limits of this range.

Near the equator, there is little temperature change throughout the year, though there may be dramatic differences in rainfall and humidity. The terms summer, autumn, winter and spring do not generally apply. Lowlands around the equator generally have a tropical rainforest climate, also known as an equatorial climate, though cold ocean currents cause some regions to have tropical monsoon climates with a dry season in the middle of the year, and the Somali Current generated by the Asian monsoon due to continental heating via the high Tibetan Plateau causes Greater Somalia to have an arid climate despite its equatorial location.

Average annual temperatures in equatorial lowlands are around 31 °C (88 °F) during the afternoon and 23 °C (73 °F) around sunrise. Rainfall is very high away from cold ocean current upwelling zones, from 2,500 to 3,500 mm (100 to 140 in) per year. There are about 200 rainy days per year and average annual sunshine hours are around 2,000. Despite high year-round sea level temperatures, some higher altitudes such as the Andes and Mount Kilimanjaro have glaciers. The highest point on the equator is at the elevation of 4,690 metres (15,387 ft), at 0°0′0″N 77°59′31″W, found on the southern slopes of Volcán Cayambe [summit 5,790 metres (18,996 ft)] in Ecuador. This is slightly above the snow line and is the only place on the equator where snow lies on the ground. At the equator, the snow line is around 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) lower than on Mount Everest and as much as 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) lower than the highest snow line in the world, near the Tropic of Capricorn on Llullaillaco.

| Climate data for Libreville, Gabon in Africa | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.5 (85.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.1 (86.2) |

29.4 (84.9) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.5 (81.5) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.4 (83.1) |

29.0 (84.2) |

28.58 (83.44) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.8 (80.2) |

27.0 (80.6) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.6 (79.9) |

26.7 (80.1) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.4 (77.7) |

25.7 (78.3) |

25.9 (78.6) |

26.2 (79.2) |

25.95 (78.71) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.1 (75.4) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.9 (75.0) |

23.1 (73.6) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.8 (71.2) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.30 (73.94) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 250.3 (9.85) |

243.1 (9.57) |

363.2 (14.30) |

339.0 (13.35) |

247.3 (9.74) |

54.1 (2.13) |

6.6 (0.26) |

13.7 (0.54) |

104.0 (4.09) |

427.2 (16.82) |

490.0 (19.29) |

303.2 (11.94) |

2,841.7 (111.88) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 17.9 | 14.8 | 19.5 | 19.2 | 16.0 | 3.70 | 1.70 | 4.90 | 14.5 | 25.0 | 22.6 | 17.6 | 177.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 176.7 | 182.7 | 176.7 | 177.0 | 158.1 | 132.0 | 117.8 | 89.90 | 96.00 | 111.6 | 135.0 | 167.4 | 1,720.9 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[9] Hong Kong Observatory[10] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Pontianak, Indonesia in Asia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 32.4 (90.3) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.2 (91.8) |

33.0 (91.4) |

33.2 (91.8) |

32.9 (91.2) |

33.4 (92.1) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.7 (90.9) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.6 (81.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

28.2 (82.8) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.7 (81.9) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.7 (81.9) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.7 (72.9) |

22.6 (72.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.1 (73.6) |

22.5 (72.5) |

22.3 (72.1) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.8 (73.0) |

22.6 (72.7) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.7 (72.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 260 (10.2) |

215 (8.5) |

254 (10.0) |

292 (11.5) |

256 (10.1) |

212 (8.3) |

201 (7.9) |

180 (7.1) |

295 (11.6) |

329 (13.0) |

400 (15.7) |

302 (11.9) |

3,196 (125.8) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 15 | 13 | 21 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 25 | 14 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 238 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN)[11] | |||||||||||||

| Climate data for Macapá, Brazil in South America | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 29.7 (85.5) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.3 (84.7) |

29.5 (85.1) |

30.0 (86.0) |

30.3 (86.5) |

30.6 (87.1) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.1 (89.8) |

32.6 (90.7) |

32.3 (90.1) |

31.4 (88.5) |

30.71 (87.28) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 26.5 (79.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.1 (82.6) |

27.9 (82.2) |

27.4 (81.3) |

27.03 (80.65) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 23.0 (73.4) |

23.1 (73.6) |

23.2 (73.8) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.2 (73.8) |

22.9 (73.2) |

23.3 (73.9) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.5 (74.3) |

23.4 (74.1) |

23.29 (73.92) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 299.6 (11.80) |

347.0 (13.66) |

407.2 (16.03) |

384.3 (15.13) |

351.5 (13.84) |

220.1 (8.67) |

184.8 (7.28) |

98.0 (3.86) |

42.6 (1.68) |

35.5 (1.40) |

58.4 (2.30) |

142.5 (5.61) |

2,571.5 (101.26) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 23 | 22 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 13 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 14 | 203 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 148.8 | 113.1 | 108.5 | 114.0 | 151.9 | 189.0 | 226.3 | 272.8 | 273.0 | 282.1 | 252.0 | 204.6 | 2,336.1 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[12] Hong Kong Observatory[13] | |||||||||||||

Line-crossing ceremonies

There is a widespread maritime tradition of holding ceremonies to mark a sailor's first crossing of the equator. In the past, these ceremonies have been notorious for their brutality, especially in naval practice. Milder line-crossing ceremonies, typically featuring King Neptune, are also held for passengers' entertainment on some civilian ocean liners and cruise ships.

See also

References

- "Equator". National Geographic - Education. 6 September 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

- "Equinox: Almost Equal Day and Night, By Aparna Kher". Retrieved 5 November 2021.

- "Definition of equator". OxfordDictionaries.com. Archived from the original on May 23, 2018. Retrieved 5 May 2018.

- William Barnaby Faherty; Charles D. Benson (1978). "Moonport: A History of Apollo Launch Facilities and Operations". NASA Special Publication-4204 in the NASA History Series. p. Chapter 1.2: A Saturn Launch Site. Archived from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

Equatorial launch sites offered certain advantages over facilities within the continental United States. A launching due east from a site on the equator could take advantage of the earth's maximum rotational velocity (460 m/s (1,510 ft/s)) to achieve orbital speed. The more frequent overhead passage of the orbiting vehicle above an equatorial base would facilitate tracking and communications. Most important, an equatorial launch site would avoid the costly dogleg technique, a prerequisite for placing rockets into equatorial orbit from sites such as Cape Canaveral, Florida (28 degrees north latitude). The necessary correction in the space vehicle's trajectory could be very expensive - engineers estimated that doglegging a Saturn vehicle into a low-altitude equatorial orbit from Cape Canaveral used enough extra propellant to reduce the payload by as much as 80%. In higher orbits, the penalty was less severe but still involved at least a 20% loss of payload.

- "Millions of Years Ago, the Poles Moved — and It Could Have Triggered an Ice Age".

- Luzum, Brian; Capitaine, Nicole; Fienga, Agnès; Folkner, William; Fukushima, Toshio; Hilton, James; Hohenkerk, Catherine; Krasinsky, George; Petit, Gérard; Pitjeva, Elena; Soffel, Michael; Wallace, Patrick (2011). "The IAU 2009 system of astronomical constants: the report of the IAU working group on numerical standards for Fundamental Astronomy" (PDF). Celest Mech Dyn Astr. 110 (4): 293–304. Bibcode:2011CeMDA.110..293L. doi:10.1007/s10569-011-9352-4. S2CID 122755461.

- "General definitions and numerical standards" (PDF). IERS Technical Note 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2018.

- Instituto Geográfico Militar de Ecuador (24 January 2005). "Memoria Técnica de la Determinación de la Latitud Cero" (in Spanish).

- "Weather Information for Libreville". World Weather Information Service. World Meteorological Organization.

- "Climatological Normals of Libreville". Hong Kong Observatory. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019.

- "Weather Information for Pontianak". World Weather Information Service. World Meteorological Organization.

- "Weather Information for Macapa". World Weather Information Service. World Meteorological Organization.

- "Climatological Normals of Macapa". Hong Kong Observatory. Archived from the original on 26 October 2019.

Sources

- Moritz, H (September 1980). "Geodetic Reference System 1980". Bulletin Géodésique. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 54 (3): 395–405. Bibcode:1980BGeod..54..395M. doi:10.1007/BF02521480. S2CID 198209711. (IUGG/WGS-84 data)

- Taff, Laurence G (1981). Computational Spherical Astronomy. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0-471-06257-X. OCLC 6532537. (IAU data)

.jpg.webp)