Economic history of Pakistan

Since independence in 1947, the economy of Pakistan has emerged as a semi-industrialized one, the on textiles, agriculture, and food production, though recent years have seen a push towards technological diversification. Pakistan's GDP growth has been gradually on the rise since 2012 and the country has made significant improvements in its provision of energy and security. However, decades of corruption and internal political conflict have usually led to low levels of foreign investment and underdevelopment.[1]

Historically, the land forming modern-day Pakistan was home to the ancient Indus Valley civilization from 2800 BC to 1800 BC, and evidence suggests that its inhabitants were skilled traders. Although the subcontinent enjoyed economic prosperity during the Mughal era, growth steadily declined during the British colonial period. Since independence, economic growth has meant an increase in average income of about 150 percent from 1950 to 1996, But Pakistan like many other developing countries, has not been able to narrow the gap between itself and rich industrial nations, which have grown faster on a per head basis. Per capita GNP growth rate from 1985 to 1995 was only 1.2 percent per annum, substantially lower than India (3.2), Bangladesh (2.1), and Sri Lanka (2.6).[2] The inflation rate in Pakistan has averaged 7.99 percent from 1957 until 2015, reaching an all-time high of 37.81 percent in December 1973 and a record low of -10.32 percent in February 1959. Pakistan suffered its only economic decline in GDP between 1951 and 1952.[3]

Overall, Pakistan has maintained a fairly healthy and functional economy in the face of several wars, changing demographics, and transfers of power between civilian and military regimes, growing at an impressive rate of 6 percent per annum in the first four decades of its existence. During the 1960s, Pakistan was seen as a model of economic development around the world, and there was much praise for its rapid progress. Many countries sought to emulate Pakistan's economic planning strategy, including South Korea, which replicated the city of Karachi's second "Five-Year Plan."

Ancient history

Indus Valley Civilization

The Indus Valley civilization, the first known permanent and predominantly urban settlement that flourished between 3500 BC to 1800 BC, featured a vibrant economic system. Its citizens practised agriculture, domesticated animals, made sharp tools and weapons from copper, bronze, and tin, and traded with other cities.[4] Archaeological excavations have uncovered streets, drainage systems, and water supplies in the valley's major cities of Harappa, Lothal, Mohenjo-daro, and Rakhigarhi, revealing an advanced knowledge of urban planning.

Although civilization had several urban centers, much of the population resided in villages, where the economy was largely isolated and self-sustaining. Agriculture was the predominant occupation, as it helped satisfy the villages' food requirements while also providing raw materials for cottage and small scale industries like textiles and handicrafts. Besides farmers, other occupational groups included barbers, carpenters, doctors (Ayurvedic practitioners), goldsmiths, weavers, etc.[5]

Through the joint family system, members of a family often pooled their resources to sustain themselves and invest in business ventures. The system ensured that younger members were trained and employed in the family business, while the elderly and disabled were supported by their families. This also prevented agricultural land from being split and reaped a higher yield due to the benefits of scale.[6]

Achaemenid Empire

_circa_480_BCE_in_the_Naqsh-e_Roastam_reliefs_of_Xerxes_I.jpg.webp)

In 518 BCE, The Achaemenid Empire conquered regions of modern day's Pakistan. The conquered area was the most fertile and populous region of the Achaemenid Empire. An amount of tribute was fixed according to the richness of each territory.[7][8] The province of the Hindush ('Ινδοι, Indoi) was the Achaemenid district paying the largest tribute, and alone represented 32% of the total tribute revenues of the whole Achaemenid Empire.[7][8] It also means that Indos was the richest Achaemenid region in the subcontinent, much richer than Gandara or Sattagydia.

Mauryan Empire

During the Maurya Empire (c. 321–185 BC), there were a number of important changes and developments in the economy of the region. For the first time, most of Indian subcontinent was unified under one ruler. With an empire in place, trade routes became more secure, thereby reducing the risks associated with the transportation of goods. The empire spent considerable resources building roads and maintaining them throughout the region. The improved infrastructure, combined with greater security, uniformity in measurements, and the increasing usage of coins as currency, all enhanced trade.[9]

Kushan Empire

After Mauryan Empire, the region came under control of Indo-Greek Kingdom, under which economy was rather vibrant as evident by their coins, art and architecture.[10][11] Afterwards Kushan Empire gained control in 1st century AD and the region prospered under them.

Medieval history

Delhi Sultanate

Many historians argue that the Delhi Sultanate was responsible for making Indian subcontinent more multicultural and cosmopolitan. According to Angus Maddison, between the years 1000 and 1500, region's GDP, of which the sultanates represented a significant part, grew nearly 80% to $60.5 billion in 1500.[12]

Mughal Empire

During the Mughal period (1526–1858) in the 16th century, the gross domestic product of the empire was estimated at about 25.1% of the world economy.

An estimate of Indian subcontinent's pre-colonial economy puts the annual revenue of Emperor Akbar's treasury in 1600 at £17.5 million (in contrast to the entire treasury of Great Britain two hundred years later in 1800, which totaled £16 million). The gross domestic product of Mughal Empire in 1600 was estimated at about 24.3 percent of the world economy, making it the second largest in the world.[13]

By the late 17th century, the Mughal Empire was at its peak and had expanded to include almost 90 percent of South Asia. In 1700, the exchequer of the Emperor Aurangzeb reported an annual revenue of more than £100 million. Mughal India was now the world's largest economy, responsible for almost a quarter of global production, as well as a sophisticated customs and taxation system within the empire.

Silk route

scholars have suggested that trading from Indian subcontinent to West Asia and Eastern Europe was active between the 14th and 18th centuries.[14][15][16] During this period,local traders settled in Surakhani, a suburb of greater Baku, Azerbaijan.

Further north, the Gangetic plains and the Indus valley housed several centres of river-borne commerce. Most overland trade was carried out via the Khyber Pass connecting the Punjab region with Afghanistan and onward to the Middle East and Central Asia.[18]

Colonial history

After gaining the right to collect revenue in Bengal in 1765, the East India Company largely ceased importing gold[19] and silver, which it had hitherto used to pay for goods shipped back to Britain.[20] In addition, as under Mughal rule, land revenue collected in the Bengal Presidency helped finance the company's wars in other part of Indian subcontinent.[20]

During the period 1780–1860, region's status shifted from being an exporter of processed goods for which it received payment in bullion, to being an exporter of raw materials and a buyer of manufactured goods.[20] Fine cotton and silk had been the main exports from Indian subcontinent to markets in Europe, Asia, and Africa in the 1750s. Yet, by the second quarter of the 19th century, raw materials, which chiefly consisted of raw cotton, opium, and indigo, accounted for most of India's exports.[21]

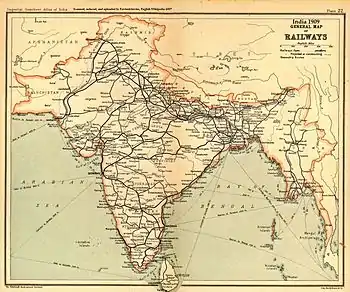

While British colonial rule stabilized institutions and strengthened law and order to a large extent, British foreign policy stifled regional trade with the rest of the world. The British built an advanced network of railways, telegraphs, and a modern bureaucratic system that is still in place today. However, the infrastructure they created was mainly geared towards the exploitation of local resources, and left the economy stagnant, stalled industrial development, and resulted in an agricultural output that was unable to feed a rapidly accelerating population.

The British economic policies were most obvious in Punjab where in 1885, the Punjab administration began an ambitious plan to transform over six million acres of barren waste land in central and western Punjab into irrigable agricultural land. The creation of canal colonies was designed to relieve demographic pressures in the central parts of the province, increase productivity and revenues, and create a loyal support amongst peasant landholders.[22] The colonisation resulted in an agricultural revolution in the province, rapid industrial growth, and the resettlement of over one million Punjabis in the new areas.[23] A number of towns were created or saw significant development in the colonies, such as Lyallpur, Sargodha and Montgomery. By the 1920s the Punjab produced a tenth of India's total cotton crop and a third of its wheat crop. Per capita output of all the crops in the province increased by approximately 45 percent between 1891 and 1921.[24]

Post-independence history

| History of modern Pakistan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-independence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-independence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| See also | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Pakistan's population has grown rapidly from around 30 million in 1947 to over 220 million in 2020. Despite this, Pakistan's average economic growth rate since independence has been higher than the average growth rate of the world economy during the same period. Average annual real GDP growth rates[25] were 6.8% in the 1960s, 4.8% in the 1970s, and 6.5% in the 1980s. Average annual growth fell to 4.6% in the 1990s with significantly lower growth in the second half of that decade. See also[26]

1950s and 1960s: Initial decades

Economic growth during the 1950s averaged 3.1 percent per annum, and the decade was marked by both political and macroeconomic instability and a shortage of resources to meet the nation's needs. After the State Bank of Pakistan was founded in 1948, a currency dispute between India and Pakistan broke out in 1949. Trade relations were strained until the issue was resolved in mid-1950. Monsoon floods between 1951–52 and 1952-53 created further economic problems, as did uneven development between East and West Pakistan.

Pakistan's economy was quickly revitalized under Ayub Khan, with economic growth averaging 5.82 percent during his eleven years in office from 27 October 1958 to 25 March 1969. Manufacturing growth in Pakistan during this time was 8.51 percent, far outpacing any other time in Pakistani history. Pakistan established its first automobile and cement industries, and the government constructed several dams, (notably Tarbela Dam and Mangla Dam), canals, and power stations, in addition to launching Pakistan's space program.

Along with heavy investment in manufacturing, Ayub's policies focused on boosting Pakistan's agricultural sector. Land reforms, the consolidation of holdings, and strict measures against hoarding were combined with rural credit programs and work programs, higher procurement prices, augmented allocations for agriculture, and improved seeds as part of the green revolution. Tax collection was low, averaging less than 10 percent of GDP.[27] The Export Bonus Vouchers Scheme (1959) and tax incentives stimulated new industrial entrepreneurs and exporters. Bonus vouchers facilitated access to foreign exchange for imports of industrial machinery and raw materials. Tax concessions were also offered for investment in less-developed areas. These measures had important consequences in bringing industry to Punjab and gave rise to a new class of small industrialists.[28]

Some academics have argued that while HYV technology enabled a sharp acceleration in agricultural growth, it was accompanied by social polarization and increased interpersonal and interregional inequality.[29] Mahbub ul Haq blamed the concentration of economic power to 22 families who were dominating the financial and economic life of the country by controlling 66 percent of industrial assets and 87 percent of banking.[30]

In 1959, the country began the construction of its new capital city.[31] A Greek firm of architects, Konstantinos Apostolos Doxiadis, designed the master plan of the city based on a grid plan which was triangular in shape with its apex towards the Margalla Hills.[32] The capital was not moved directly from Karachi to Islamabad; it was first shifted temporarily to Rawalpindi in the early sixties and then to Islamabad when the essential development work was completed in 1966.[33]

Economy of East Bengal in Pakistan

The partition of British India and the emergence of India and Pakistan in 1947 severely disrupted the country's economic system. The united government of Pakistan expanded its cultivated area and some irrigation facilities, but the rural population generally became poorer between 1947 and 1971 because improvements did not keep pace with the rural population increase.[34] Pakistan's five-year plans opted for a development strategy based on industrialization, but the major share of the development budget went to West Pakistan, that is, contemporary Pakistan.[34] A lack of natural resources meant that East Pakistan was heavily dependent on imports, creating a balance of payments problem.[34] Without a substantial industrialization program or adequate agrarian expansion, the economy of East Pakistan steadily declined.[34] Blame was placed by various observers, but especially by those in East Pakistan, on the West Pakistani leaders who not only dominated the government, but also most of the fledgling industries in East Pakistan.[34]

1970s: Nationalization and command economy

Tarbela Dam, the largest earth filled dam in the world, was constructed in 1968.

Tarbela Dam, the largest earth filled dam in the world, was constructed in 1968. Prime Minister Secretariat in the new capital city

Prime Minister Secretariat in the new capital city Spread over 1700 acres, Quaid-i-Azam University was constructed in 1967.

Spread over 1700 acres, Quaid-i-Azam University was constructed in 1967. Pakistan Steel Mills was constructed in 1973, making it the largest industrial mega-corporation, having a production capacity of 5.0 million tonnes of steel.

Pakistan Steel Mills was constructed in 1973, making it the largest industrial mega-corporation, having a production capacity of 5.0 million tonnes of steel.

Economic mismanagement in general, and fiscally imprudent economic policies in particular, caused a large increase in the country's public debt and led to slower growth in the 1970s. Two wars with India - the Second Kashmir War in 1965 and the separation of Bangladesh from Pakistan also adversely affected economic growth.[35] In particular, the latter war brought the economy close to recession, although economic output rebounded sharply until the nationalization of the mid-1970s. Large generous aid from the United States also declined after the global oil crisis in 1973, which had a further negative impact on the economy.[36]

According to Muhammad Abrar Zahoor, the nationalization of industries can be divided into two phases. The first phase started soon after the PPP came into power and was motivated by distributional concerns – to bring under state control the financial and physical capital controlled by a tiny corporate elite. However, in 1974, the influence and authority of the left wing within the party significantly decreased: they had either been marginalized or purged.5 As a result, the second phase was less ideologically motivated, and was instead driven by the outcome of ad hoc responses to various situations.6 Between 1974 and 1976, the style of economic management Bhutto adopted reduced the role of the Planning Commission as well as its capacity to offer advice to political decision-makers. Corruption grew exponentially and access to state corridors became a primary avenue of accumulating a private fortune. In this way, groups and individuals in command of state institutions used public intervention in the economy "as a means for extending their wealth and power."[37]

Bhutto introduced socialist economics policies while working to prevent any further division of the country. Major heavy mechanical, chemical, and electrical engineering industries were immediately nationalized, as were banks, insurance companies, educational institutions, and other private organizations. Industries such as KESC were now under complete government control. Bhutto abandoned Ayub Khan's state capitalism policies, and introduced socialist policies in a move to reduce the rich get richer and poor get poorer ratio. Bhutto also established Port Qasim, Pakistan Steel Mills, the Heavy Mechanical Complex (HMC) and several cement factories. However, economic growth slowed in the wake of nationalization, with growth rates falling from an average of 6.8 percent per annum in the 1960s to 4.8 percent per annum on average in the 1970s. Most nationalized units went into loss because decisions were not market-based. Bhutto's government also failed to meet distributional objectives. Poverty and income inequality increased compared to the previous decade and the rate of inflation rose, averaging 16 percent from 1971 to 1977.[38]

1980s-1999: Era of privatization and stagnation

Pakistan developed the first motorway in South Asia in 1997; today it has expanded to a 1,502 km long network.

Pakistan developed the first motorway in South Asia in 1997; today it has expanded to a 1,502 km long network. The Soviet–Afghan War significantly affected the economy of Pakistan, with approximately 1.7 million Afghani refugees moving to Pakistan.

The Soviet–Afghan War significantly affected the economy of Pakistan, with approximately 1.7 million Afghani refugees moving to Pakistan. Benazir Bhutto twice led the country during this period and promoted social-capitalist policies.

Benazir Bhutto twice led the country during this period and promoted social-capitalist policies. Jinnah International Airport was greatly expanded in 1994, making it a regional aviation hub.

Jinnah International Airport was greatly expanded in 1994, making it a regional aviation hub.

| Periods | GDP growth rate↓ (according to Sartaj Aziz) | Inflation rate↑ (according to Sartaj Aziz) |

|---|---|---|

| 1988-89 | 4.88%[39] | 10.39%[39] |

| 1989-90 | 4.67%[39] | 6.04%[39] |

| 1990-91 | 5.48%[39] | 12.66%[39] |

| 1991-92 | 7.68%[39] | 9.62%[39] |

| 1992-93 | 3.03%[39] | 11.66%[39] |

| 1993-94 | 4.0%[39] | 11.80%[39] |

| 1994-95 | 4.5%[39] | 14.5%[39] |

| 1995-96 | 1.70% | 10.79%[40] |

Pakistan's economy recovered significantly during the 1980s via a policy of deregulation, as well as an increased inflow of foreign aid and remittances from expatriate workers. Under Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, "many of the controls on industry were liberalized or abolished, the balance of payments deficit was kept under control, and Pakistan became self-sufficient in all basic foodstuffs with the exception of edible oils."[38] As a result, Pakistan's rate of GDP growth rose to an average of 6.5 percent per annum in the 1980s. According to Sushil Khanna,[41] professor at the Indian Institute of Mass Communication, the completion of the long gestation period of Tarbela Dam also helped unleash unprecedented agricultural growth, while fertilizer and cement investments made in the 1970s contributed to industrial growth. A tremendous boost to economic activity was provided by rising worker remittances, which reached a peak of US$3 billion in 1982–83, equivalent to 10 percent of the gross national product of Pakistan. Zia also successfully negotiated with the United States for larger external assistance. In addition to supplying direct aid to Pakistan, the U.S. and its allies funneled about US$5–7 billion to the Afghan Mujahideen through Pakistan, further uplifting the local economy. Under Zia, economic policies became market oriented, rather than socialist.[42]

Pakistan's economy in the 1990s suffered from poor governance and low growth as it alternated between the Pakistan Peoples Party under Benazir Bhutto and the Pakistan Muslim League (N) led by Nawaz Sharif. The GDP growth rate sank to 4 percent and Pakistan faced persistent fiscal and external deficits, triggering a debt crisis. Exports stagnated and Pakistan lost its market share in a buoyant world trade environment. Poverty nearly doubled from 18 to 34 percent, causing the Human Development Index of the United Nations Development Programme to rank Pakistan in one of its lowest development categories during this time period.

While both the Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto governments supported economic liberalization and privatization policies, neither were able to successfully implement them.[43] Both parties have argued that this was due to interruptions in the democratic process, as well as unpredictable and difficult political circumstances, such as sanctions imposed after Pakistan's nuclear tests in 1998. Although the stock market did improve in Sharif's second term and inflation was contained at 3.5 percent, as opposed to 7 percent in 1993–96, Pakistan still experienced low development and high unemployment.[44]

2000s: Economic liberalization, growth and re-stagnation

JF-17 Thunder became the first indigenous combat aircraft produced by the country.

JF-17 Thunder became the first indigenous combat aircraft produced by the country. The poverty expenditure rate statistically dropped to 34.5%—17.2% in 2008 as part of the privatization programme.

The poverty expenditure rate statistically dropped to 34.5%—17.2% in 2008 as part of the privatization programme. PTCL was privatized in 2005, and boosted revenue of over $1 billion.

PTCL was privatized in 2005, and boosted revenue of over $1 billion. Statue of a bull outside Islamabad Stock Exchange

Statue of a bull outside Islamabad Stock Exchange

Following a military coup in October 1999, Pervez Musharraf became the President of Pakistan in 2001 and worked to address the challenges of "heavy external and domestic indebtedness; high fiscal deficit and low revenue generation capacity; rising poverty and unemployment; and a weak balance of payments with stagnant exports."[38] At this time, the country lacked the foreign exchange reserves needed to cover its imports or service its debts, remittances and investments had decreased by millions, and Pakistan had no access to private capital markets.

Yet, sound structural policies coupled with improved economic management accelerated growth between 2002 and 2007. Approximately 11.8 million new jobs were created during Musharraf's term from 1999 to 2008, while primary school enrollment rose and the debt-to-GDP ratio dropped from 100 to 55 percent. Pakistan's reserves increased from US$1.2 billion in October 1999 to US$10.7 billion on 30 June 2004. The rate of inflation fell, while the investment rate grew to 23 percent of GDP, and an estimated $14 billion of foreign private capital inflows financed many sectors of the economy. The exchange rate also remained fairly stable throughout this period. All revenue collection targets were met on time and allocation for development was increased by about 40 percent.[45] These gains can be attributed largely to debt reduction and economic reforms, but also to the procurement of billions of dollars' worth of U.S. aid to Pakistan in return for Pakistan's support in the US-led war on terror.

After Musharraf's resignation in 2008 due to mounting legal and public pressures, the PPP government once again resumed control of Pakistan. The administrations of Asif Ali Zardari and Syed Yousaf Raza Gillani oversaw a dramatic rise in violence, corruption, and unsustainable economic policies that forced Pakistan to re-enter an "era of stagflation."[46][47][48] The Pakistan economy slowed down to around 4.09 percent, as opposed to the 8.96 to 9.0 percent rate under Musharraf and Shaukat Aziz in 2004–08, while the yearly growth rate fell from a long-term average of 5.0 percent to around 2.0 percent.[47] In its calculations, the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics pointed out that the "nation's currency in circulation as a percentage of total deposits is 31 percent, which is very high compared to India,"[49] and its tight monetary policy has been unable to tame inflation, and only slowed down economic growth because the private sector is no longer playing a key role.[48] Analyzing the stagflation problem, the PIDE observed that a major cause of the continuous era of stagflation in Pakistan was a lack of coordination between fiscal and monetary authorities.[48][49]

2010s: Privatization and liberalization

3000 km long China–Pakistan Economic Corridor construction began in 2015.

3000 km long China–Pakistan Economic Corridor construction began in 2015. Pakistan rolled out 4G in 2014, aiming to capitalize on over 140 million mobile phones in the country.

Pakistan rolled out 4G in 2014, aiming to capitalize on over 140 million mobile phones in the country. Several mass transit systems have been developed throughout Pakistan.

Several mass transit systems have been developed throughout Pakistan.

| Fiscal year | GDP growth | Inflation rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2013–14[50] | ||

| 2014–15 | ||

| 2015–16 |

In 2013, Nawaz Sharif returned to inherit an economy crippled by energy shortages, hyperinflation, mild economic growth, high debt, and a large budget deficit. Shortly after taking office, Pakistan "embarked on a $6.3 billion IMF Extended Fund Facility, which focused on reducing energy shortages, stabilizing public finances, increasing revenue collection, and improving its balance of payments position."[1] Lower oil prices, better security, higher remittances, and consumer spending spurred growth toward a seven-year high of 4.3 percent in the fiscal year 2014-15[55] and foreign reserves increased to US$10 billion. In May 2014, the IMF confirmed that inflation had dropped to 13 percent in 2014 compared to 25 percent in 2008,[56] prompting Standard & Poor's and Moody's Corporation to change Pakistan's ranking to a stable outlook on their long-term ratings.[57][58][59]

The IMF loan program concluded in September 2016. Although Pakistan missed several structural reform criteria, it restored macroeconomic stability, improved its credit rating, and boosted growth. The Pakistani rupee has remained relatively stable against the US dollar since 2015, though it declined about 10 percent between November 2017 and March 2018.[1] Balance of payments concerns have also reemerged as a result of a significant increase in imports and weak export and remittance growth. In its South Asian Growth report, the World Bank stated: "In Pakistan, gradual recovery to around 4.5 per cent growth by 2016 is aided by low inflation and fiscal consolidation. Increases in remittances and stable agricultural performance contribute to this outcome. But further acceleration requires tackling pervasive power cuts, a cumbersome business environment, and low access to finance."[60] In his 2016 book, The Rise and Fall of Nations, Ruchir Sharma opined that Pakistan's economy is in its 'take-off' stage and termed the future outlook for 2020 'very good,’ predicting that Pakistan would transform from a "low-income to a middle-income country during the next five years."[61]

In 2016, articles by Forbes and Reuters declared Pakistan's economy to be on track to becoming an emerging market in Asia, and affirmed that Pakistan's expanding middle class is key to the country's economic prospects.[62][63] On 7 November 2016, Bloomberg News also claimed that "Pakistan is on the verge of an investment-led growth cycle."[64] On 10 January 2017, The Economist forecasted Pakistan's GDP to grow at 5.3 percent in 2017, making it the fifth fastest growing economy in the world and the fastest growing in the Muslim world.[65][66]

2022-2023 Pakistani economic crisis

Due to the Russian Invasion of Ukraine in 2022, oil prices rose worldwide.[67] This was one of the many contributing factors that led to the draining of Pakistan's Foreign Exchange Reserves.[68] Excessive external borrowings by the country over the years had also raised the spectre of default. This speculation caused the currency to fall, making imports much more expensive, putting more strain on the Forex Reserves.[69]

This combined with factors like poor governance, low productivity per capita and the 2022 Pakistan Floods resulted in a balance of payment crisis.[70] This has triggered the country taking desperate steps to persuade IMF to resume its $6 Billion bailout deal.[71]

See also

References

- CIA: The World Factbook

- Learning from the Past: A Fifty-year Perspective on Pakistan’s Development

- "Is Pakistan's economy in recession?". The Express Tribune. 1 February 2013.

- Marshall, John (1996). Mohenjo-Daro and the Indus Civilization: Being an Official Account of Archaeological Excavations at Mohenjo-Daro Carried Out by the Government of India Between the Years 1922 and 1927. p. 481. ISBN 9788120611795.

- Chopra, Pran Nath (2003). A Comprehensive History of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set). Sterling. p. 73. ISBN 9788120725034.

- Sarien, R. G. (1973). Managerial styles in India: proceedings of a seminar. p. 19.

- Zosia Archibald; John K. Davies; Vincent Gabrielsen, eds. (2011). The economies of Hellenistic societies, third to first centuries BC. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 404. ISBN 9780199587926.

- Herodotus Book III, 89-95

- Ratan Lal Basu & Rajkumar Sen: Ancient Indian Economic Thought, Relevance for Today, ISBN 81-316-0125-0, Rawat Publications, New Delhi, 2008.

- "Those tiny territories of the Indo-Greek kings must have been lively and commercially flourishing places", India: The ancient past, Burjor Avari, p. 130

- "No doubt the Greeks of Bactria and India presided over a flourishing economy. This is clearly indicated by their coinage and the monetary exchange they had established with other currencies." Narain, "The Indo-Greeks" 2003, p. 275.

- Madison, Angus (6 December 2007). Contours of the world economy, 1–2030 AD: essays in macro-economic history. Oxford University Press. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-19-922720-4.

- Maddison, Angus (2006). The world economy, Volumes 1–2. OECD Publishing. p. 638. doi:10.1787/456125276116. ISBN 978-92-64-02261-4. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- Hanway, Jonas (1753), An Historical Account of the British Trade Over the Caspian Sea, Sold by Mr. Dodsley,

... The Persians have very little maritime strength ... their ship carpenters on the Caspian were mostly Indians ... there is a little temple, in which the Indians now worship

- Stephen Frederic Dale (2002), Indian Merchants and Eurasian Trade, 1600–1750, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-52597-8,

... The Russian merchant, F.A. Kotov ... saw in Isfahan in 1623, both Hindus and Muslims, as Multanis.

- Scott Cameron Levi (2002), The Indian diaspora in Central Asia and its trade, 1550–1900, BRILL, ISBN 978-90-04-12320-5,

... George Forster ... On the 31st of March, I visited the Atashghah, or place of fire; and on making myself known to the Hindoo mendicants, who resided there, I was received among these sons of Brihma as a brother

- Museums, Reserves, Galleries of Baku — National Tourism Promotion Bureau, 2017.

- Raychaudhuri & Habib 2004, pp. 10–13

- khan, Noman. "Today Gold Rate in Pakistan". Financeupdates.

- Robb 2004, pp. 131–134

- Peers 2006, pp. 48–49

- Imran Ali, THE PUNJAB CANAL COLONIES, 1885-1940, 1979, The Australian National University, Canberra, p34

- Ian Talbot, Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India, Routledge, 16 December 2013, p,55

- Talbot, Ian A. (2007). "Punjab Under Colonialism: Order and Transformation in British India" (PDF). Journal of Punjab Studies. 14 (1): 3–10.

- 2005-06 Economic and Social Indicators of Pakistan Archived 4 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- National Accounts (current prices) Archived 13 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "How golden was Ayub Khan's era?". tribune.com.pk. 14 May 2012.

- "Export Bonus Scheme – A Review". Economic Digest. 3 (4): 39–48. 1960. JSTOR 41242976.

- THE GREEN REVOLUTION

- "Richest families in Pakistan - The 22 Families". paycheck.pk.

- Jonathan M. Bloom, ed. (23 March 2009). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art & Architecture. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0195309911. Retrieved 2 July 2012.

- CDA Islamabad. "History of Islamabad". Archived from the original on 12 May 2016.

- Maneesha Tikekar (1 January 2004). Across the Wagah: An Indian's Sojourn in Pakistan. Promilla. pp. 23–62. ISBN 978-8185002347. Retrieved 12 May 2012.

- Lawrence B. Lesser. "Historical Perspective". A Country Study: Bangladesh (James Heitzman and Robert Worden, editors). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (September 1988). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.About the Country Studies / Area Handbooks Program: Country Studies - Federal Research Division, Library of Congress

- Pakistan Embassy Archived 16 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Butt, Muhammad Shoaib and Bandara, Jayatilleke S. (2008) Trade liberalization and regional disparity in Pakistan. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0203887182

- A Critical Appraisal of the Economic Reforms under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto: An Assessment

- Economic Profile of Pakistan 1947-2014

- Aziz, Sartaj (18 May 1995). "The Curse of Stagflation". Sartaj Aziz. Islamabad: Sartaj Aziz published at the Dawn News. p. 1. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- PGovt. "Related Data From the International Monetary Fund". Pakistan Inflation Index Monitoring Cell. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Sushil Khanna

- The Crisis in the Pakistan Economy

- Tripod Publications, Pakistan. "Economic Liberalisation and Privatization". Tripod Publications, Pakistan. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- "Sartaj defends Nawaz's economic policies". Daily Times, Pakistan. 29 November 2002. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- Regrouping Pakistan. United States: Oxford Business Group. 2008. ISBN 9781902339740. Retrieved 30 May 2012.

- Iqbal, Javed. "Stagflation and power outage". 3 August 2012. Lahore Times, 3 August 2012. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Niaz Murtaza (22 February 2011). "An economic dilemma". Dawn News, An economic dilemma. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- Syed Fazl-e-Haider, Special to Gulf News (20 January 2011). "Stagflation hits poor hard in Pakistan". Gulf News. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- 23 February 2012 (23 February 2012). "Steps urged to boost bank deposits". Dawn Newspapers, February 2012. Retrieved 7 August 2012.

- "Dar's 2013 budget speech – the highs and the very low lows". The Express Tribune. 25 May 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- HIGHLIGHTS OF PAKISTAN ECONOMIC SURVEY 2013-14

- "FY14: FDI clocks in at $1.63 billion, up 11.99%". The Express Tribune. 16 July 2014. Retrieved 8 January 2016.

- Economic Survey 2014-15: Ishaq Dar touts economic growth amidst missed targets

- Pakistan: Economy

- "Articles". strategicforesight.com.

- "Pakistan's economy improving: IMF". The Express Tribune. 25 May 2010.

- "Foreign currency reserves cross $10b mark". The Express Tribune. 2 April 2014.

- "Outlook stable: S&P affirms Pakistan's ratings at 'B-/B'". The Express Tribune. 1 April 2014.

- "Improving inflows: Moody's changes Pakistan's rating outlook to 'stable'". The Express Tribune. 14 July 2014.

- "Pakistan's GDP to grow by 4.5% in current fiscal year, WB forecasts". Retrieved 11 February 2016.

- "Pakistan's economy ready for takeoff | TNS - The News on Sunday". tns.thenews.com.pk. 18 September 2016. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- "Pakistan's economy is back on track, says top US magazine - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- "Despite rising economy, Pakistan still hampered by image problem". Reuters. 19 June 2016. Retrieved 20 June 2016.

- FaseehMangi, Faseeh Mangi (7 November 2016). "China's Billions Luring Once Shy Foreign Investors to Pakistan". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- "Pakistan predicted to be world's fastest-growing Muslim economy in 2017 - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 10 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- "Economic and financial indicators". The Economist. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

- Kearney, Laila (30 December 2022). "Oil ends year of wild price swings with 2nd straight annual gain". Reuters. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- "Economic crisis and default fear". The Express Tribune. 13 June 2022. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Hussain, Abid. "Pakistan foreign exchange reserves drop to lowest since 2014". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Khawaja, Haroon (27 February 2023). "Beyond default — Iran via the US". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- "Pakistan's New Budget Aims to Please the IMF". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

Works cited

- Peers, Douglas M. (2006), India under Colonial Rule 1700–1885, Harlow and London: Pearson Longmans, ISBN 978-0582317383.

- Raychaudhuri, Tapan; Habib, Irfan (2004). The Cambridge Economic History of India, Volume I : c. 1200 – c. 1750. New Delhi: Orient Longman. ISBN 978-81-250-2709-6.

- Robb, Peter (2004), A History of India (Palgrave Essential Histories), Houndmills, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-69129-8.