A Mighty Fortress Is Our God

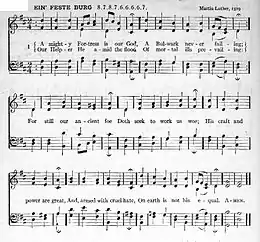

"A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" (originally written in the German language with the title "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott") is one of the best known hymns by the Protestant Reformer Martin Luther, a prolific hymnwriter. Luther wrote the words and composed the hymn tune between 1527 and 1529.[1] It has been translated into English at least seventy times and also into many other languages.[1][2] The words are mostly original, although the first line paraphrases that of Psalm 46.[3]

| Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott | |

|---|---|

| Hymn by Martin Luther | |

Walter's manuscript copy of "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" | |

| Key | C Major/D Major |

| Catalogue | Zahn 7377 |

| Written | c. 1529 |

| Text | by Martin Luther |

| Language | German |

| Based on | Psalm 46 |

| Meter | 8.7.8.7.6.6.6.6.7 |

| Melody | by Martin Luther |

| Published | c. 1531 (extant) |

| ⓘ | |

| "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" | |

|---|---|

| Written | 1853 |

| Text | by Frederick H. Hedge (translator) |

History

"A Mighty Fortress" is one of the best known hymns of the Lutheran tradition, and among Protestants more generally. It has been called the "Battle Hymn of the Reformation" for the effect it had in increasing the support for the Reformers' cause. John Julian records four theories of its origin:[1]

- Heinrich Heine: "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" was sung by Luther and his companions as they entered Worms on 16 April 1521 for the Diet;

- K. F. T. Schneider: it was a tribute to Luther's friend Leonhard Kaiser, who was executed on 16 August 1527;

- Jean-Henri Merle d'Aubigné: it was sung by the German Lutheran princes as they entered Augsburg for the Diet in 1530, at which the Augsburg Confession was presented; and

- Some scholars believe that Luther composed it in connection with the Diet of Speyer (1529), at which the German Lutheran princes lodged their protest to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who wanted to enforce his 1521 Edict of Worms.

Alternatively, John M. Merriman writes that the hymn "began as a martial song to inspire soldiers against the Ottoman forces" during the Ottoman wars in Europe.[4]

The earliest extant hymnal in which it appears is that of Andrew Rauscher (1531). It is believed to have been included in Joseph Klug's Wittenberg hymnal of 1529, of which no copy remains. Its title was Der xxxxvi. Psalm. Deus noster refugium et virtus.[1] Before that it is believed to have appeared in Hans Weiss Wittenberg's hymnal of 1528, also lost.[5] This evidence supports Luther having written it between 1527 and 1529, because Luther's hymns were printed shortly after he wrote them.

Tune

Luther composed the melody, named Ein feste Burg from the text's first line, in meter 87.87.55.56.7 (Zahn No. 7377a). This is sometimes denoted "rhythmic tune" to distinguish it from the later isometric variant, in 87.87.66.66.7-meter (Zahn No. 7377d), which is more widely known and used in Christendom.[6][7] In 1906 Edouard Rœhrich wrote, "The authentic form of this melody differs very much from that which one sings in most Protestant churches and figures in (Giacomo Meyerbeer's) The Huguenots. ... The original melody is extremely rhythmic, by the way it bends to all the nuances of the text ..."[8]

While 19th-century musicologists disputed Luther's authorship of the music to the hymn, that opinion has been modified by more recent research; it is now the consensus view of musical scholars that Luther did indeed compose the famous tune to go with the words.

Reception

Heinrich Heine wrote in his 1834 essay Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland, a history of emancipation in Germany beginning with the Reformation, that Ein feste Burg was the Marseillaise of the Reformation.[9] This "imagery of battle" is also present in some translations, such as that of Thomas Carlyle (which begins "A safe stronghold our God is still").[10] In Germany, "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" was historically also used as a patriotic paean, which is why it was regularly sung at nationalistic events such as the Wartburg Festival in 1817.[11] This patriotic undertone of the hymn emanates from its importance for the Reformation in general, which was regarded by the Protestants not only as a religious but as a national movement delivering Germany from Roman oppression.[12] Furthermore, the last line of the fourth stanza of the German text, "Das Reich muss uns doch bleiben," which is generally translated into English as "The Kingdom's ours forever," referring to the Kingdom of God, may also be interpreted as meaning the Holy Roman Empire must remain with the Germans.

The song is reported to have been used as a battle anthem during the Thirty Years War by forces under King Gustavus Adolphus, Lutheran king of Sweden. This idea was exploited by some 19th-century poets, such as Karl Curths, although there exists no primary source which supports this.[13] The hymn had been translated into Swedish already in 1536, presumably by Olaus Petri, with the incipit, "Vår Gud är oss en väldig borg".[14] In the late 19th century the song also became an anthem of the early Swedish socialist movement.

In addition to being consistently popular throughout Western Christendom in Protestant hymnbooks, it is now a suggested hymn for Catholic Masses in the U.S.,[15] and appears in the Catholic Book of Worship published by the Canadian Catholic Conference in 1972.[16] The eventful history and reception of A Mighty Fortress Is Our God has been presented interactively in Lutherhaus Eisenach’s revamped permanent exhibition since 2022.[17]

English translations

The first English translation was by Myles Coverdale in 1539 with the title, "Oure God is a defence and towre". The first English translation in "common usage" was "God is our Refuge in Distress, Our strong Defence" in J.C. Jacobi's Psal. Ger., 1722, p. 83.[1]

An English version less literal in translation but more popular among Protestant denominations outside Lutheranism is "A mighty fortress is our God, a bulwark never failing", translated by Frederick H. Hedge in 1853. Another popular English translation is by Thomas Carlyle and begins "A safe stronghold our God is still".

Most North American Lutheran churches have not historically used either the Hedge or Carlyle translations. Traditionally, the most commonly used translation in Lutheran congregations is a composite translation from the 1868 Pennsylvania Lutheran Church Book ("A mighty fortress is our God, a trusty shield and weapon"). In more recent years a new translation completed for the 1978 Lutheran Book of Worship ("A mighty fortress is our God, a sword and shield victorious") has also gained significant popularity.

Compositions based on the hymn

The hymn has been used by numerous composers, including Johann Sebastian Bach. There is a version for organ, BWV 720, written early in his career, possibly for the organ at Divi Blasii, Mühlhausen.[18] He used the hymn as the basis of his chorale cantata Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, BWV 80 written for a celebration of Reformation Day. Bach also set the tune twice in his Choralgesänge (Choral Hymns), BWV 302 and BWV 303 (for four voices). Two orchestrations of Bach's settings were made by conductors Leopold Stokowski and Walter Damrosch. Dieterich Buxtehude also wrote an organ chorale setting (BuxWV 184), as did Johann Pachelbel. George Frideric Handel used fragments of the melody in his oratorio Solomon. Georg Philipp Telemann also made a choral arrangement of this hymn and prominently used an extract of the verses beginning Mit unsrer Macht ist nichts getan in his famous Donnerode.

Felix Mendelssohn used it as the theme for the fourth and final movement of his Symphony No. 5, Op. 107 (1830), which he named Reformation in honor of the Reformation started by Luther. Joachim Raff wrote an Overture (for orchestra), Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott, Op. 127. Giacomo Meyerbeer quoted it in his five-act grand opera Les Huguenots (1836), and Richard Wagner used it as a "motive" in his "Kaisermarsch" ("Emperor's March"), which was composed to commemorate the return of Kaiser Wilhelm I from the Franco-Prussian War in 1871.[1][3] Two organ settings were written by Max Reger: his chorale fantasia Ein' feste Burg ist unser Gott, Op. 27, and a much shorter chorale prelude as No. 6 of his 52 Chorale Preludes, Op. 67, in 1902. Claude Debussy quoted the theme in his suite for piano duet, En blanc et noir.[19] Alexander Glazunov quoted the melody in his Finnish Fantasy, Op. 88.[20]

Ralph Vaughan Williams used the tune in his score for the film 49th Parallel, most obviously when the German U-boat surfaces in Hudson Bay shortly after the beginning of the film. Flor Peeters wrote an organ chorale setting "Ein feste Burg" as part of his Ten Chorale Preludes, Op. 69, published in 1949. More recently it has been used by band composers to great effect in pieces such as Psalm 46 by John Zdechlik and The Holy War by Ray Steadman-Allen. The hymn also features in Luther, an opera by Kari Tikka that premiered in 2000.[21][22] It has also been used by African-American composer Julius Eastman in his 1979 work Gay Guerrilla, composed for an undefined number of instruments and familiar in its recorded version for 4 pianos. Eastman's use of the hymn can arguably be seen as simultaneously a claim for inclusion in the tradition of "classical" composition, as well as a subversion of that very same tradition.[23]

Mauricio Kagel quoted the hymn, paraphrased as "Ein feste Burg ist unser Bach", in his oratorio Sankt-Bach-Passion, which tells Bach's life and was composed for the tricentenary of Bach's birth in 1985. Nancy Raabe composed a concertato on the hymn using organ, assembly, trumpet, and tambourine, the only such composition by a female composer.[24]

See also

References

- Julian, John, ed., A Dictionary of Hymnology: Setting forth the Origin and History of Christian Hymns of All Ages and Nations, Second revised edition, 2 vols., n.p., 1907, reprint, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1957, 1:322–25

- W. G. Polack, The Handbook to the Lutheran Hymnal, Third and Revised Edition (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1958), 193, No. 262.

- Marilyn Kay Stulken, Hymnal Companion to the Lutheran Book of Worship (Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981), 307–08, nos. 228–229.

- Merriman, John (2010). A History of Modern Europe: From the Renaissance to the Age of Napoleon. Vol. 1 (3 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-393-93384-0.

- Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut Lehmann, eds., Luther's Works, 55 vols. (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House; Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1957–1986), 53:283.

- Cf. The Commission on Worship of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod, Lutheran Worship, (St. Louis: CPH, 1982), 992, 997.

- Zahn, Johannes (1891). Die Melodien der deutschen evangelischen Kirchenlieder (in German). Vol. IV. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann. pp. 396–398.

- E. Rœhrich, Les Origines du Choral Luthérien. (Paris: Librairie Fischbacher, 1906), 23 (italics original): "La forme authentique de cette mélodie diffère beaucoup de celle qu'on chante dans la plupart des Églises protestantes et qui figure dans les Huguenots". ... La mélodie originelle est puissamment rythmée, de manière à se plier à toutes les nuances du texte ..."

- Goetschel, Willi (28 January 2007). "Zur Geschichte der Religion und Philosophie in Deutschland [On the History of Religion and Philosophy in Germany]" (PDF). The Literary Encyclopedia. University of Toronto.

- Watson, J. R. (2002). An Annotated Anthology of Hymns. OUP Oxford. p. 67. ISBN 978-0-19-826973-1.

- "Lutherchoral 'Ein feste Burg' – Religion, Nation, Krieg" (in German). Luther2017. Archived from the original on 26 December 2013.

- James R. Payton Jr., Getting the Reformation Wrong. Correcting Some Misunderstandings, page 82.

- Loewe, Andreas; Firth, Katherine (8 June 2018). "Martin Luther's "Mighty Fortress"". Lutheran Quarterly. 32 (2): 125–145. doi:10.1353/lut.2018.0029. ISSN 2470-5616. S2CID 195008166.

- Psalmer och sånger (Örebro: Libris; Stockholm: Verbum, 1987), Item 237, which uses Johan Olof Wallin's 1816 revision of the translation attributed to Petri. The first line is "Vår Gud är oss en väldig borg."

- Cantica Nova

- Catholic Book of Worship hymnary.org

- Ausstellung im Lutherhaus erweitert (in German), ZeitOnline, May 10, 2022 (retrieved May 23, 2022).

- "Ein Feste Burg". All of Bach. Retrieved 18 December 2022.

- Laki, Peter. "En Blanc et Noir / About the Work". Kennedy Center. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "Tracing Martin Luther's great hymn through musical history". Gramophone. 29 November 2017.

- Luther: An opera about a man between God and the Devil – Composed by Kari Tikka

- Volker Tarnow. "Luther lebt: Deutsche Momente" in Die Welt, 5 October 2004

- Ryan Dohoney, "A Flexible Musical Identity: Julius Eastman in New York City, 1976-90," in Gay Guerrilla, ed. Renée Levine Packer and Mary Jane Leach (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2015), 123.

- "Nancy M Raabe, Choral Octavos and Vocal Solos". nancyraabe.com. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

Bibliography

- Commission on Worship of the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. Lutheran Worship. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1982. ISBN

- Julian, John, ed. A Dictionary of Hymnology: Setting forth the Origin and History of Christian Hymns of all Ages and Nations. Second revised edition. 2 vols. n.p., 1907. Reprint, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1957.

- Pelikan, Jaroslav and Lehmann, Helmut, eds. Luther's Works. Vol. 53, Liturgy and Hymns. St. Louis, Concordia Publishing House, 1965. ISBN 0-8006-0353-2.

- Polack, W. G. The Handbook to the Lutheran Hymnal. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1942.

- Rœhrich, E. Les Origines du Choral Luthérien. Paris: Librairie Fischbacher, 1906.

- Stulken, Marilyn Kay. Hymnal Companion to the Lutheran Book of Worship. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1981.

External links

- Literature about Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott in the German National Library catalogue

- "Ein feste Burg ist unser Gott" (Martin Luther): Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- "Ein feste Burg" sung by the Wartburg Choir (in German)

- "A Mighty Fortress Is Our God" sung by the Choir of King's College, Cambridge

- "Ein feste Burg" sung in the original rhythm (Evangelische Landeskirche in Württemberg) (in German)