Guayana Esequiba

Guayana Esequiba (Spanish pronunciation: [ɡwaˈʝana eseˈkiβa] ⓘ), sometimes also called Esequibo or Essequibo, is a disputed territory of 159,500 km2 (61,600 sq mi) west of the Essequibo River that is administered and controlled by Guyana but claimed by Venezuela.[1][2] The boundary dispute was inherited from the colonial powers (Spain in the case of Venezuela, and the Netherlands and the United Kingdom in the case of Guyana) and has been complicated by the independence of Guyana from the United Kingdom in 1966.

.png.webp)

The status of the territory is subject to the Geneva Agreement, which was signed by the United Kingdom, Venezuela and British Guiana on 17 February 1966. This treaty stipulates that the parties will agree to find a practical, peaceful and satisfactory solution to the dispute.[3] Should there be a stalemate, according to the treaty, the decision as to the means of settlement is to be referred to an "appropriate international organ" or, failing agreement on this point, to the Secretary-General of the United Nations.[3] The Secretary-General referred the entire matter to the International Court of Justice. On 18 December 2020, the ICJ accepted the case submitted by Guyana to settle the dispute.[4]

The territory is divided by Guyana into six administrative regions: Barima-Waini, Cuyuni-Mazaruni, Pomeroon-Supenaam, Potaro-Siparuni, Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo and Essequibo Islands-West Demerara. Venezuela often depicts it on the map as a striped region. It is included in the state constitutions of Bolívar and Delta Amacuro.

The Spanish name is either Guayana Esequiba or Territorio del Esequibo, and in Venezuelan maps it often appears as Zona en Reclamación, which translates to Zone in Reclamation.

Demographics

| Region of Guyana | Population (2012) |

|---|---|

| Barima-Waini | 26,941 |

| Cuyuni-Mazaruni | 20,280 |

| Pomeroon-Supenaam | 46,810 |

| Potaro-Siparuni | 10,190 |

| Upper Takutu-Upper Essequibo | 24,212 |

| Essequibo Islands-West Demerara | 107,416 |

| Combined population of claimed regions | 235,849 |

Colonial history

15th century

The first European encounter of the region was by the ships of Juan de Esquivel, deputy of Don Diego Columbus, son of Christopher Columbus, in 1498.[6] The region was named after Esquivel. In 1499, Amerigo Vespucci and Alonso de Ojeda explored the mouths of the Orinoco, and reportedly were the first Europeans to explore the Essequibo.[6] In 1581, on the banks of the Pomeroon River, Dutch colonists from Zeeland established a trading post and were colonizing the land situated west of the Essequibo.[7] The Pomeroon colony was incorporated into the Essequibo colony and would become a major destination for trade for the Dutch colonialists before control was transferred to the British.

16th century

Dutch colonisation of the Guianas occurred primarily between the mouths of the Orinoco River in the west and the Amazon River to the east.[8] Their presence in the Guianas was noted by the late 1500s, though many documents of early Dutch discoveries in the region were destroyed.[8] The Dutch were present as far west as the Araya Peninsula in Venezuela utilising salt pans in the area.[8] By the 1570s, it was reported that the Dutch were commencing trade in the Guianas, but little evidence of this exists.[8] At the time, neither the Portuguese nor the Spanish had made any establishments in the area.[8] A Dutch fort was built in 1596 at the mouth of the Essequibo River on an island, which was destroyed by the Spanish later that year.[8]

In 1597, Dutch interest in travelling to the Guianas became common following the publication of The Discovery of Guiana by Sir Walter Raleigh.[8] On 3 December 1597, a Dutch expedition left Brielle and travelled the coasts between the Amazon and Orinoco.[8] The report, written by A. Cabeljau and described as having "more realistic information about the region" than that of Raleigh, showed how the Dutch had travelled the Orinoco and Caroní River, discovering dozens of rivers and other land previously unknown.[8] Cabeljau wrote of good relations with the natives and that the Spanish were friendly when they encountered them in San Tomé.[8] By 1598, Dutch ships frequented Guiana to establish settlements.[8]

17th century

.jpg.webp)

Another Dutch fort supported by indigenous groups was established at the mouth of the Essequibo River in 1613, which was destroyed by the Spanish in November 1613.[8] In 1616, Dutch ship captain Aert Adriaenszoon Groenewegen established Fort Kyk-Over-Al located 20 miles (32 km) down the Essequibo River, where he married the daughter of an indigenous chief, controlling the Dutch colony for nearly fifty years until his death in 1664.[8]

To protect the Araya salt flats, the "white gold" of the time, from English, French and Dutch incursions, the Spanish Crown ordered the construction of a military fortress, which they finished building at the beginning of the year 1625. It was given the name of Real Fuerza de Santiago de Arroyo de Araya, (Santiago, by the patron of Spain; Arroyo, by the governor Diego de Arroyo Daza and Araya, by the name of the place). It was the first important fortress of the captaincy of Venezuela. As the years passed, the Spanish Crown was concerned about the high cost of maintaining the fortress. In 1720 it had 246 people, and a budget of 31,923 strong pesos per year to which is added the serious damage to the structure caused by the earthquake in 1684 and later the devastating effects of the hurricane that flooded the salt flats in 1725.

By 1637, the Spanish wrote that the Dutch "In those three settlements of Amacuro, Essequibo and Berbis the [Dutch] have many people... all the Aruacs and Caribs are allied with him", with later reports of the Dutch building forts from Cape North at the Amazon River to the opening of the Orinoco River.[8] In 1639, the Spanish stated that the Dutch in Essequibo "were further protected by 10,000 to 12,000 Caribs in the vicinity of which they frequent, and who are their allies".[8] Captain Groenewegen was recognised as keeping both the Spanish and Portuguese from settling in the area.[8]

In a speech to the Parliament of England that took place on 21 January 1644, English settlers who had explored the Guianas stated that the Dutch, English and Spanish had long sought to find El Dorado in the region.[9] The English said that the Dutch were experienced with travelling the Orinoco River for many years.[9] Due to their skillful travel of the Dutch on the Orinoco, the Spanish would later encounter the Dutch and prohibit them from travelling the river.[9]

In 1648 Spain signed the Peace of Münster with the Dutch Republic, whereby Spain recognised the Republic's independence and also small Dutch possessions located east of the Essequibo River, which had been founded by the Dutch Republic before it was recognised by Spain. However, few decades after the Peace of Münster, the Dutch began to spread gradually west of the Essequibo River, inside the Spanish Guayana Province. These new settlements were regularly contested and destroyed by the Spanish authorities.

Serious Dutch colonisation west of the Essequibo began in the early 1650s, while the colony of Pomeroon being established between the Moruka River and Pomeroon River.[8] Many of these colonists were Dutch-Brazilian Jews who had left Pernambuco.[8] In 1673, Dutch settlements were established as far as the Barima River.[8]

18th century

.jpg.webp)

In 1732, the Swedes made an attempt to settle[10] between Low Orinoco and the Barima River.[11] Nevertheless, by 1737 Major Sergeant Carlos Francisco de Sucre y Pardo (Antonio José de Sucre's grandfather) expelled them from the forts at Barima,[12] preventing the Swedish attempt at colonisation for the time being.[13][14] By 1745, the Dutch had several territories in the region, including Essequibo, Demerara, Berbice, and Surinam.[6] Dutch settlements were also established on the Cuyuni River, Caroní River and Moruka River.[15] Domingos, Bandeira Jerónimo and Roque described Essequibo and Demerara as "sophisticated and promising slave colonies".[15]

When Spain created the Captaincy General of Venezuela in 1777, the Essequibo River was restated as the natural border between Spanish territory and the Dutch colony of Essequibo.[16] Spanish authorities, in a report dated 10 July 1788, put forward an official claim against the Dutch expansion over her territory, and proposed a borderline:

It has been stated that the south bank of the Orinoco from the point of Barima, 20 leagues more or less inland, up to the creek of Curucima, is low-lying and swampy land and, consequently, reckoning all this tract as useless, very few patches of fertile land being found therein, and hardly any savannahs and pastures, it is disregarded; so taking as chief base the said creek of Curucima, or the point of the chain and ridge in the great arm of the Imataka, an imaginary line will be drawn running to the south-south-east following the slopes of the ridge of the same name which is crossed by the rivers Aguire, Arature and Amacuro, and others, in the distance of 20 leagues, direct to the Cuyuni; from there it will run on to the Masaruni and Essequibo, parallel to the sources of the Berbis and Surinama; this is the directing line of the course which the new Settlements and foundations proposed must follow.

Dutch slaves in Essequibo and Demerara recognised the Orinoco River as the boundary between Spanish and Dutch Guiana, with slaves often attempting to cross the Orinoco to live with increased, though limited, liberties in Spanish Guiana.[15]

19th century

Under the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814, the Dutch colonies of Demerara, Berbice and Essequibo were transferred to the United Kingdom. By this time, the Dutch had defended the territory from the British, French and Spanish for nearly two centuries,[6] often allying with natives in the region who provided intelligence about Spanish incursions and escaped slaves.[15] According to scholar Allan Brewer Carías, the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1814 did not establish a western border of what would later be known as the British Guiana, which is why explorer Robert Schomburgk would later be commissioned to draw a border.[16]

Following the establishment of Gran Colombia in 1819, territorial disputes began between Gran Colombia, later Venezuela, and the British.[17] In 1822 José Rafael Revenga, Minister Plenipotentiary of Gran Colombia to Britain, complained to the British government at the direction of Simón Bolívar about the presence of British settlers in territory claimed by Venezuela: "The colonists of Demerara and Berbice have usurped a large portion of land, which according to recent treaties between Spain and Holland, belongs to our country at the west of Essequibo River. It is absolutely essential that these settlers be put under the jurisdiction and obedience to our laws, or be withdrawn to their former possessions."[18]

In 1824 Venezuela appointed José Manuel Hurtado as its new Ambassador to Britain. Hurtado officially presented to the British government Venezuela's claim to the border at the Essequibo River, which was not objected to by Britain.[19] However, the British government continued to promote colonisation of territory west of the Essequibo River in succeeding years. In 1831, Britain merged the former Dutch territories of Berbice, Demerara, and Essequibo into a single colony, British Guiana.

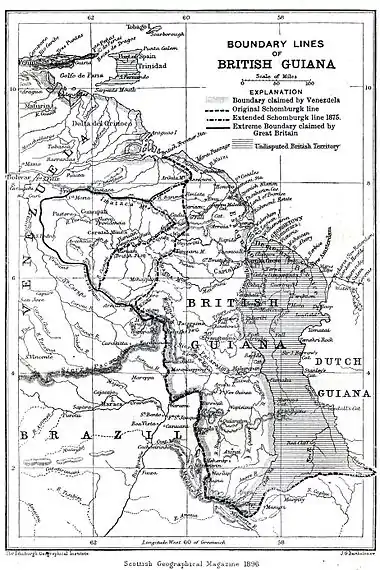

Schomburgk Line

Under the aegis of the Royal Geographical Society, the German-born explorer and naturalist Robert Hermann Schomburgk conducted botanical and geographical exploration of British Guiana in 1835. This resulted in a sketch of the territory with a line marking what he believed to be the western boundary claimed by the Dutch. As a result of this, he was commissioned in 1840 by the British government to survey Guiana's boundaries. This survey resulted in what came to be known as the "Schomburgk Line".[20][21] The line went well beyond the area of British occupation and gave British Guiana control of the mouth of the Orinoco River.[22] According to Schomburgk, it did not contain all the area that Britain might legitimately claim.

Venezuela disputed Schomburgk's placing of border markers at the Orinoco River, and in 1844 claimed all of Guiana west of the Essequibo River. In the same year, a British proposal to Venezuela to modify the border to give Venezuela full control of the Orinoco River mouth and adjacent territory was ignored. In 1850, Britain and Venezuela reached an agreement whereby they accepted not to colonise the disputed territory, although it was not established where this territory began and ended.[20]

Schomburgk's initial sketch, which had been published in 1840, was the only version of the "Schomburgk Line" published until 1886, which led to later accusations by US President Grover Cleveland that the line had been extended "in some mysterious way".[20]

Gold discoveries

The dispute went unmentioned for many years until gold was discovered in the region, which disrupted relations between the United Kingdom and Venezuela.[23] In 1876, gold mines inhabited mainly by English-speaking people had been established in the Cuyuni basin, which was Venezuelan territory beyond the Schomburgk line but within the area Schomburgk thought Britain could claim. That year, Venezuela reiterated its claim up to the Essequibo River, to which the British responded with a counterclaim including the entire Cuyuni basin, although this was a paper claim the British never intended to pursue.[20]

On 21 February 1881, Venezuela proposed a frontier line starting from a point one mile to the north of the Moruka River, drawn from there westward to the 60th meridian and running south along that meridian. This would have granted the Barima District to Venezuela.

In October 1886 Britain declared the Schomburgk Line to be the provisional frontier of British Guiana, and in February 1887 Venezuela severed diplomatic relations. In 1894, Venezuela appealed to the United States to intervene, citing the Monroe Doctrine as justification. The United States did not want to get involved, only going as far as suggesting the possibility of arbitration.[20]

Venezuela crisis of 1895

The longstanding dispute became a diplomatic crisis in 1895, when Venezuela hired William Lindsay Scruggs as its lobbyist in Washington, D.C. Scruggs took up Venezuela's argument that British action violated the Monroe Doctrine. Scruggs used his influence to get the US government to accept this claim and get involved. President Grover Cleveland adopted a broad interpretation of the Doctrine that did not just simply forbid new European colonies but declared an American interest in any matter within the hemisphere.[24] British Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and British ambassador to the US Lord Pauncefote both misjudged the importance the American government placed on the dispute.[25][26] The key issue in the crisis became Britain's refusal to include the territory east of the Schomburgk Line in the proposed international arbitration. Ultimately Britain backed down and tacitly accepted the US right to intervene under the Monroe Doctrine. This US intervention forced Britain to accept arbitration of the entire disputed territory.[27]

Treaty of Washington and arbitration

The Treaty of Arbitration between the UK and Venezuela was signed in Washington on 2 February 1897. This treaty specifically stipulated the legal framework for the arbitration, its first article stating that "An Arbitral Tribunal shall be immediately appointed to determine the boundary-line between the Colony of British Guiana and the United States of Venezuela."

The Treaty provided the legal framework, procedures and conditions for the Tribunal in order to solve the issue and reach to determinate a border. Its third article established that "The Tribunal shall investigate and ascertain the extent of the territories belonging to, or that might lawfully be claimed by the United Netherlands or by the Kingdom of Spain respectively at the time of the acquisition by Great Britain of the Colony of British Guiana, and shall determine the boundary line between the Colony of British Guiana and the United States of Venezuela". The Treaty also established the rules and principles to be followed by the Tribunal in order to draw the borderline.[28]

Venezuela argued that Spain–whose territory they had acquired–controlled land from the Orinoco River to the Amazon River in present-day Brazil.[22] Spain, according to Venezuela, only designated its claimed Guiana territory to the Dutch, which did not include much land within the disputed territory.[22] Meanwhile, Britain, who had acquired the Dutch territory, stated that the disputed Guiana region was not Spanish because it was so remote and uncontrolled, explaining that the original natives in the land had shared the territory's land with the Dutch instead of the Spanish and were thus under Dutch and British influence.[22]

The rival claims were presented to a tribunal of five arbitrators: two from Britain, two from the US (representing Venezuela's interest) and one from Russia, who were presumed neutral. Venezuela reiterated its claim to the district immediately west of the Essequibo, and claimed that the boundary should run from the mouth of the Moruka River southwards to the Cuyuni River, near its junction with the Mazaruni River, and then along the east bank of the Essequibo to the Brazilian border.

On 3 October 1899 the Tribunal ruled largely in favour of Britain. The Schomburgk Line was, with two deviations, established as the border between British Guiana and Venezuela.[20] One deviation was that Venezuela received Barima Point at the mouth of the Orinoco, giving it undisputed control of the river, and thus the ability to levy duties on Venezuelan commerce. The second placed the border at the Wenamu River rather than the Cuyuni River, giving Venezuela substantial territory east of the line. However, Britain received most of the disputed territory, and all of the gold mines.[29]

The Venezuelan representatives, claiming that Britain had unduly influenced the decision of the Russian member of the tribunal, protested the outcome. Periodic protests, however, were confined to the domestic political arena and international diplomatic forums.[30]

Immediate reactions

In 1899, immediately after the arbitration ruling, the US counsel for Venezuela were interviewed jointly, and pointed out their first claims against the ruling:

"Great Britain, up to the time of the intervention of the United States, distinctly refused to arbitrate any portion of the territory east of the Schomburgk line, alleging that its title was unassailable. This territory included the Attacuri River and Point Barima, which is of the greatest value strategically and commercially. The award gives Point Barima, with a strip of land fifty miles long, to Venezuela, which thereby obtains entire control of the Orinoco River. Three thousand square miles in the interior are also awarded to Venezuela. Thus, by a decision in which the British arbitrators concurred, the position taken by Great Britain in 1895 is shown to be unfounded [...] The President of the tribunal in his closing address today had commented upon the unanimity of the present judgment and had referred to it as a proof of the success of the arbitration, but it did not require much intelligence to penetrate behind this superficial statement and to see that the line drawn is a line of compromise and not a line of right. If the British contention was right, the line should have been drawn further west; if it were wrong, the line should have been drawn much further east. There was nothing in the history of the controversy, nor in the legal principle involved, which could adequately explain why the line should be drawn where it had been. So long as arbitration was conducted on such principles, it could not be regarded as a success, at least by those who believe that arbitration should result in the admission of legal rights and not in compromises really diplomatic in character. Venezuela had gained much, but was entitled to much more, and if the arbitrators were unanimous, it must be because their failure to agree would have confirmed Great Britain in the possession of even more territory".[31]

The Venezuelan government showed almost immediate disapproval with the 1899 Arbitral Award. As early as 7 October 1899, Venezuela voiced its condemnation of the Award, and demanded the renegotiation of her eastern border with British Guiana: that day, Venezuelan Foreign Minister José Andrade stated that the Arbitral Award was the product of political collusion and it should not be adhered to by Venezuela.[32][33]

20th century

Renewed dispute

On 26 October 1899 in a letter to a colleague, Severo Mallet-Prevost, the Official Secretary of the US–Venezuela delegation in the Tribunal of Arbitration, stated that the Arbitral Award was the result of pressures brought on the judges by the President of the Tribunal, Friedrich Martens.[34]

After numerous bilateral diplomatic attempts failed to convince the United Kingdom of its seriousness to nullify the award, Venezuela denounced it before the first assembly of the United Nations in 1945.[32][33]

In 1949, the US jurist Otto Schoenrich gave the Venezuelan government a memorandum written by Mallet-Prevost, which was written in 1944 to be published only after his death. Mallet-Prevost surmised from the private behavior of the judges that there had been a political deal between Russia and Britain,[34] and said that the Russian chair of the panel, Friedrich Martens, had visited Britain with the two British arbitrators in the summer of 1899, and subsequently had offered the two American judges a choice between accepting a unanimous award along the lines ultimately agreed, or a 3 to 2 majority opinion even more favourable to the British. The alternative would have followed the Schomburgk Line entirely, and given the mouth of the Orinoco to the British. Mallet-Prevost said that the American judges and Venezuelan counsel were disgusted at the situation and considered the 3 to 2 option with a strongly worded minority opinion, but ultimately went along with Martens to avoid depriving Venezuela of even more territory.[34] This memorandum provided further motives for Venezuela's contentions that there had in fact been a political deal between the British judges and the Russian judge at the Arbitral Tribunal, and led to Venezuela's revival of its claim to the disputed territory.[35][36]

By the 1950s, Venezuelan media led grassroots movements demanding the acquisition of Guayana Esequiba.[23] Under the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez, the Venezuelan government began plans to invade Guayana Esequiba.[37] President Pérez Jiménez anticipated the invasion of Guyana in 1958, but was ultimately overthrown in the 1958 Venezuelan coup d'état before this was finalised.[37]

United Nations General Assembly complaint

Venezuela formally raised the issue again at an international level before the United Nations in 1962, four years before Guyana won independence from Britain.[23] On 12 November 1962, Venezuelan foreign minister Marcos Falcón Briceño gave an exposition in the Special Political and Decolonization Committee of the United Nations General Assembly to denounce the 1899 Paris Tribunal Arbitration, Citing the Mallet-Prevost Memorandum. Briceño argued that collusion and nullity vices led to the favourable ruling, and his exposition he stressed that Venezuela considered the Paris Arbitration as null and void because of "acts contrary to good faith" of the British government and the Tribunal members. Said complaints led to the 1966 Geneva Agreement. Venezuela also cited as several improprieties and vices in the ruling, especially Ultra Vires, due to the fact that the referees drew the border between British Guiana, Brazil and Suriname, and also decreed freedom of navigation in the Amacuro and Barima rivers, exceeding the scope of powers granted by the arbitration treaty in 1897.

The Venezuelan claim of the nullity of the 1899 ruling has been acknowledged by several foreign scholars and jurists, such as J. Gillis Wetter of Sweden, in his work The International Arbitral Process (1979), awarded by the American Society of International Law. By searching on the British official archives, Wetter provided further evidence of the deal between Britain and Russia, what made him conclude that the ruling was marred by serious procedural and substantive defects, evidence that it was more a political compromise than a court ruling. Uruguayan jurist Eduardo Jiménez de Aréchaga, former president of the International Court of Justice, came to similar conclusions.

Geneva Agreement

At a meeting in Geneva on 17 February 1966, the governments of British Guiana, the United Kingdom and Venezuela signed the "Agreement to resolve the controversy over the frontier between Venezuela and British Guiana", best known thereafter as the Geneva Agreement of 1966. The agreement established the regulatory framework to be followed by the parties in order to resolve the issue. According to the agreement a Mixed Commission was installed with the purpose of seeking satisfactory solutions for the practical settlement of the border controversy,[38] but the parties never agreed to implement a solution within this Commission due to different interpretations of the agreement.

- Guyana argued that prior to starting the negotiations over the border issue, Venezuela should prove that the Arbitral Award of 1899 was null and void. Guyana did not accept that the 1899 decision was invalid, and held that its participation on the commission was only to resolve Venezuela's assertions.

- Rather than that, the Venezuelan counterparts argued that the Commission did not have a juridical nature or purpose but a deal-making one, so it should go ahead to find "a practical and satisfactory solution", as agreed in the treaty. Venezuela also claimed that the nullity of the Arbitral Award of 1899 was implicit, or otherwise the existence of the agreement would be meaningless.

The fifth article of the Geneva Agreement established the status of the disputed territories. The provisions state that no acts or activities taking place on the disputed territories while the Agreement is in force "shall constitute a basis for asserting, supporting or denying a claim to territorial sovereignty." The agreement also has a provision prohibiting both nations from pursuing the issue except through official inter-government channels.

In its note of recognition of the independence of Guyana on 26 May 1966, Venezuela stated:

Venezuela recognises as territory of the new State the one which is located on the east of the right bank of the Essequibo River, and reiterates before the new State, and before the international community, that it expressly reserves its rights of territorial sovereignty over all the zone located on the west bank of the above-mentioned river. Therefore, the Guyana-Essequibo territory over which Venezuela expressly reserves its sovereign rights, limits on the east by the new State of Guyana, through the middle line of the Essequibo River, beginning from its source and on to its mouth in the Atlantic Ocean.

Annexation of Ankoko Island

Five months after Guyana's independence from the United Kingdom, Venezuelan troops began their occupation of Ankoko island and surrounding islands in October 1966. Venezuelan troops quickly constructed military installations and an airstrip.[39]

Subsequently, on the morning of the 14 October 1966, Forbes Burnham, as Prime Minister and Minister of External Affairs of Guyana, dispatched a protest to the Foreign Minister of Venezuela, Ignacio Iribarren Borges, demanding the immediate withdrawal of Venezuelan troops and the removal of installations they had established.[40] Venezuelan minister Ignacio Iribarren Borges replied stating "the Government of Venezuela rejects the aforementioned protest, because Anacoco Island is Venezuelan territory in its entirety and the Republic of Venezuela has always been in possession of it".[40] The island remained under Venezuelan administration, where a Venezuelan airport and a military base operated.[41]

Rupununi Uprising

Following the 1968 Guyanese elections, the First Conference of Amerindian Leaders, named the "Cabacaburi Congress", presented demands to Prime Minister Forbes Burnham, representing the community of around 40,000 indigenous people of the Rupununi district.[42] The movement defended the integration of natives to Guyanese society, inconsonant with Bunham's Afrocentrist policies.[43] Factions within the indigenous society in South Esequibo felt threatened by the possible distribution of agricultural parcels among the sectors that had supported the Minister, which caused some of the inhabitants to rebel.[43] Guyanese Agriculture Minister, Robert Jordan, declared that the government would not recognise the inhabitants' land ownership certifications and warned that the zone would be occupied by the Afro-Guyanese population. After these declarations, Valerie Hart was appointed as president of the Provisional Government Committee of Rupununi.[44]

At a 23 December 1968 meeting, rebels finalised plans of a separated Rupununi state.[45] In an effort to receive support from Venezuela, Hart and her rebels stated that they would grant Venezuela control of Guyana's disputed Guayana Esequiba territory in exchange for assistance.[46] Rebels began their attacks on Lethem in the morning of 2 January 1969, killing five police officers and two civilians while also destroying buildings belonging to the Guyanese government with bazooka fire.[47] The rebels locked citizens in their homes and blocked airfields in Lethem, Annai Good Hope, Karanambo and Karasabai, attempting to block staging areas for Guyanese troops.[45] News about the insurrection reached Georgetown by midday prompting the deployment of policemen and soldiers of the Guyana Defence Force (GDF).[45] GDF troops arrived at an open airstrip 5 miles (8.0 km) away from Lethem.[45] As troops approached, the rebels quickly fled and the uprising ended.[45] About thirty of the rebels were arrested following the uprising.[47]

The day after the uprising, on the afternoon of 3 January 1969, Hart met in Caracas with the Venezuelan Foreign Affairs Minister Ignacio Iribarren Borges at the Yellow House, the headquarters of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Hart explained the uprising to Iribarren Borges, citing Burnham's policies as its motives, and said that the rebels had the intention of turning the Rupununi into an independent territory under Venezuelan protection. Iribarren Borges replied that Venezuela was bound to the 1966 Geneva Agreement with the United Kingdom and Guyana, and that Venezuela could not intervene in favour of the rebels even if it wanted to.[44] Members of the failed uprising fled to Venezuela for protection after their plans unraveled, with Hart and her rebels being granted Venezuelan citizenship by birth since they were recognised as being born in the Guayana Esequiba disputed territory.[43][48]

After the uprising, Venezuela President Rafael Caldera and Burnham were alarmed at the uprising and vowed to focus their attentions on the issue of the territorial dispute between their two countries. Their concern led to the Port of Spain Protocol in 1970.[43]

Port of Spain Protocol

In 1970, after the expiration of the Mixed Commission established according to the Geneva Agreement, Presidents Rafael Caldera and Forbes Burnham signed the Port of Spain Protocol, which declared a 12-year moratorium on Venezuela's reclamation of Guayana Esequiba, with the purpose of allowing both governments to promote cooperation and understanding while the border claim was in abeyance. The protocol was formally signed by the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Venezuela Aristides Calvani, Guyana State Minister for Foreign Affairs Shridath Ramphal and British High Commissioner to Trinidad and Tobago Roland Hunte.[49] The Parliament of Guyana voted for the agreement on 22 June 1970, with only People's Progressive Party voting against believing that the United Nations should resolve the matter.[49] MPs from almost all parties in the Parliament of Venezuela voiced their sharp criticism of the agreement.[49] Venezuelan maps produced since 1970 show the entire area from the eastern bank of the Essequibo, including the islands in the river, as Venezuelan territory. On some maps, the western Essequibo region is called the "Zone in Reclamation".[50]

In 1983, the deadline of the Port of Spain Protocol expired, and the Venezuelan President Luis Herrera Campins decided not to extend it anymore and resume the effective claim over the territory. Since then, the contacts between Venezuela and Guyana within the provisions of the Treaty of Geneva are under the recommendations of a UN Secretary General's representative, who can occasionally be changed under agreement by both parties.[3] Diplomatic contacts between the two countries and the Secretary General's representative continue, but there have been some clashes. The Norwegian Dag Nylander appointed in March 2017 is the latest personal representative in these efforts selected by the UN Secretary General António Guterres. It was stated that if by December 2017 the UN understood that there was no "significant progress" in resolving the dispute, Guterres would refer the case to the International Court of Justice in The Hague, unless the two countries explicitly requested it not to do so. In January 2018, the UN referred the case.[51]

21st century

Chávez administration

President Hugo Chávez eased border tensions with Guyana under advice of his mentor Fidel Castro.[52] In 2004, Chávez said, during a visit in Georgetown, Guyana, that he considered the dispute to be finished.[52]

In September 2011, Guyana made an application before the United Nations' Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf in order to extend its continental shelf by a further 150 nautical miles (280 km; 170 mi). Since the Commission requests that the areas to be considered cannot be subject to any kind of territorial disputes, the Guyanese application disregarded the Venezuelan claim over Guayana Esequiba, by saying that "there are no disputes in the region relevant to this submission of data and information relating to the outer limits of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles [370 km; 230 mi]."[53] Venezuela sent an objection to the commission, rejecting the Guyanese application and warning that Guyana had proposed a limit for its continental shelf including "the territory west of the Essequibo river, which is the subject of a territorial sovereignty dispute under the Geneva Agreement of 1966 and, within this framework, a matter for the good offices of the Secretary-General of the United Nations". Venezuela also said that Guyana consulted its neighbours Barbados, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago before making the application, but did not do the same with Venezuela. "Such a lack of consultation with the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, serious in itself in that it violates the relevant rules, is inexplicable in so far as the coast whose projection is used by the Republic of Guyana in its attempt to extend the limits forms part of the disputed territory over which Venezuela demands and reiterates its claim to sovereignty rights", said the Venezuelan communiqué.[54]

Oil discovery in Guyana

On 10 October 2013, the Venezuelan Navy detained an oil exploration vessel conducting seafloor surveys on behalf of the government of Guyana. The ship and its crew were escorted to the Venezuelan Margarita Island to be prosecuted. The Guyanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs said the vessel was in Guyanese waters,[55] but its Venezuelan counterpart sent a diplomatic note to Guyana stating that the ship was conducting oil research in Venezuelan waters with no authorisation from the country, and demanded an explanation.[56] The vessel, Teknik Perdana, together with its crew, was released the next week, but its captain was charged with violating the Venezuelan exclusive economic zone.[57]

Despite diplomatic protests from Venezuela, the government of Guyana awarded the American oil corporation Exxon a licence to drill for oil in the disputed maritime area in early 2015.[58] In May the government of Guyana announced that Exxon had indeed found promising results in their first round of drilling on the so-called Stabroek Block, an area offshore the Guayana Esequiba territory with a size of 26,800 km2 (10,300 sq mi). The company announced that further drillings would take place in the coming months to better evaluate the potential of the oil field.[59] Venezuela responded to the declaration with a decree issued on 27 May 2015, including the maritime area in dispute in its national marine protection sphere, thus extending the area that the Venezuelan Navy controls into the disputed area. This in turn caused the government of Guyana to summon the Venezuelan ambassador for further explanation.[60] The tensions have further intensified since and Guyana withdrew the operating licence of Conviasa, the Venezuelan national airline, stranding a plane and passengers in Georgetown.[61]

On 7 January 2021 there was the issuance of the Decree No. 4415 by the President of Venezuela, Nicolas Maduro, with the support of Venezuela's National Assembly, which seeks to reinforce Venezuela's claim to Guyana's Essequibo Region and its attendant maritime space.

International Court of Justice

In 2018, Secretary-General of the United Nations António Guterres concluded that the Good Offices Process had not determined a peaceful conclusion.[62] Guterres chose to have the controversy settled by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on whether the 1899 award was valid.[62] On 29 March, Guyana introduced a request in the ICJ to solve the territorial dispute.[63] Venezuela proposed Guyana to restore the diplomatic contacts to attempt to find a solution regarding the territorial dispute, arguing that Guterres "exceeded the competences given to him as the Good Offices Figure" and that the decision "contravenes the spirit, purpose and reason of the Geneva Agreement".[64] The Venezuelan government also stated that it did not recognise the jurisdiction of the Court as mandatory.[65]

On 19 June, Guyana announced that it would ask the Court to rule on their favour citing Article 53 of the ICJ Estatute, which establishes that "if any of the two parties does not show at the tribunal or fails to defend their case, the other party has the right to communicate with the court and to rule in favour of their claim".[66][67] In July 2018, the government of Nicolás Maduro argued that the ICJ did not hold jurisdiction over the dispute and said that Venezuela would not participate in the proceedings.[68][69] The Court stated that Guyana would have until 19 November to present their arguments and Venezuela would have until 18 April 2019 to present their counter arguments.[70] During the Venezuelan presidential crisis, disputed acting President Juan Guaidó and the pro-opposition National Assembly of Venezuela ratified the territorial dispute over the territory.[52]

The oral audiences were planned to take place from 23 to 27 March 2020,[71] where the ICJ would determine if they held jurisdiction in the dispute, however this was delayed indefinitely due to the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic.[72] Venezuela did not take part in the hearings which were rescheduled for 30 June.[73][74] On 18 December 2020, the Court ruled that it had jurisdiction and accepted the case.[75]: 2 On 8 March 2021, Venezuela was given until 8 March 2023 to submit a counter-memorial.[75]: 3

On 18 September 2020, the United States announced that it would join Guyana on sea patrols in the area.[76]

The first agreement in the negotiations between the Maduro government and the Venezuelan opposition in Mexico in September 2021 was to act jointly in the claim of Venezuelan sovereignty over Essequibo.[77]

See also

Notes

- British Guiana Boundary: Arbitration with the United States of Venezuela. The Case (and Appendix) on Behalf of the Government of Her Britannic Majesty Volume 7. Printed at the Foreign office, by Harrison and sons, 1898.

- "Caribbean Nations Have High Hopes For the Biden-Harris Administration". South Florida Caribbean News. 20 January 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Agreement to resolve the controversy over the frontier between Venezuela and British Guiana (Treaty of Geneva, 1966) from UN

- Summary of the Judgement of 18 December 2020

- "Guyana Population and Housing Census 2012" (PDF). Government of Guyana. 2012. p. 6. Retrieved 23 June 2022.

- The Statesman's Yearbook 2017: The Politics, Cultures and Economies of the World (153 ed.). Springer Publishing. 28 February 2017. p. 566. ISBN 978-1349683987.

- "De menschetende aanbidders der zonneslang". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1907. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- Goslinga, Cornelis (1971). The Dutch in the Caribbean and on the Wild Coast. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida Press.

- Osborne, Thomas (1747). A Collection of Voyages and Travels: Consisting of Authentic Writers in Our Own Tongue. pp. 749–755.

- "Boundary Between British Guiana and Venezuela: Case Presented on the Part of the Government of Her Britannic Majesty to the Tribunal of Arbitration Constituted Under Article I of the Treaty Concluded at Washington on the 2nd February, 1897, Between Her Britannic Majesty and the United States of Venezuela". 1899.

- "The Swedish Pioneer Historical Quarterly". 1960.

- "Carlos Sucre y Pardo | Real Academia de la Historia".

- "Historisk tidskrift". 1899.

- Civrieux, Jean-Marc de (1976). "Los caribes y la conquista de la Guayana española: Etnohistoria kari'ña".

- Domingos, Nuno; Bandeira Jerónimo, Miguel; Roque, Ricardo (2019). Resistance and colonialism : insurgent peoples in world history. Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-3030191672.

- "¿Cuál es la historia detrás del conflicto territorial de la Zona en Reclamación?". Prodavinci (in Spanish). 9 April 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Pamphlets on the Venezuelan Question. 1896. pp. 63–65.

- "Simón Bolívar acérrimo defensor del Esequibo - Jesús Sotillo Bolívar en Red Angostura". Red Angostura (in Spanish). 20 August 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Ramírez Cuicas, Tulio (June 2019). "El Diferendo por el Territorio Esequibo en los Textos Escolares Venezolanos y Guyaneses" (PDF). Universidad Católica Andrés Bello: 58.

- Humphreys, R. A. (1967), "Anglo-American Rivalries and the Venezuela Crisis of 1895", Presidential Address to the Royal Historical Society 10 December 1966, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 17: pp 131–164

- "THE BEGINNING OF THE GUYANA-VENEZUELA BORDER DISPUTE". guyana.org. 2009. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- King, Willard L. (2007) Melville Weston Fuller – Chief Justice of the United States 1888–1910, Macmillan. p249

- Ince, Basil A. (1970). "The Venezuela-Guyana Boundary Dispute in the United Nations". Caribbean Studies. 9 (4): 5–26.

- Zakaria, Fareed, From Wealth to Power (1999). Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01035-8. pp145–146

- Gibb, Paul, "Unmasterly Inactivity? Sir Julian Pauncefote, Lord Salisbury, and the Venezuela Boundary Dispute," Diplomacy and Statecraft, Mar 2005, Vol. 16 Issue 1, pp 23–55

- Blake, Nelson M. "Background of Cleveland's Venezuelan Policy," American Historical Review, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Jan. 1942), pp. 259–277 in JSTOR

- http://cartografialaguayanaesequiba.blogspot.com/2014/10/la-evidencia-cartografica-de-los.html

- Treaty of arbitration between Venezuela and Great Britain, signed at Washington and dated the second day of February, 1897

- King (2007:260)

- Globalsecurity.org, "Venezuela – Guyana Relations"

- "Venezuelan Award: the decision of the Commission regarded as a Compromise", in Saint John Daily Sun, Canada. October 4, 1899. p. 8

- Kissler, Betty Jane, Venezuela-Guyana boundary dispute :1899–1966, University of Texas (USA, 1972). pages 166, 172

- Kaiyan Homi Kaikobad, Interpretation and Revision of International Boundary Decisions, Cambridge Studies in International and Comparative Law (Cambridge University, U.K., 2007). p. 43

- Schoenrich, Otto, "The Venezuela-British Guiana Boundary Dispute", July 1949, American Journal of International Law. Vol. 43, No. 3. p. 523. Washington, DC. (USA).

- Isidro Morales Paúl, Análisis Crítico del Problema Fronterizo "Venezuela-Gran Bretaña", in La Reclamación Venezolana sobre la Guayana Esequiba, Biblioteca de la Academia de Ciencias Económicas y Sociales. Caracas, 2000, p. 200.

- de Rituerto, Ricardo M. Venezuela reanuda su reclamación sobre el Esequibo, El País, Madrid, 1982.

- Hopkins, Jack W. (1984). Latin America and Caribbean Contemporary Record: 1982-1983, Volume 2. Holmes & Meier Publishers. ISBN 9780841909618.

- Treaty of Geneva 1966, Document Retrieval, UN Department of Political Affairs

- Hopkins, Jack W. (1984). Latin America and Caribbean Contemporary Record: 1982-1983, Volume 2. Holmes & Meier Publishers. ISBN 9780841909618.

- "Raúl Leoni paró en seco a Guyana en la Isla Anacoco (documento)". La Patilla. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Raúl Leoni paró en seco a Guyana en la Isla Anacoco (documento)". La Patilla. 26 September 2011. Archived from the original on 2 December 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- Amerindian News Georgetown: vol 2, No 3, May 15th 1968.

- González, Pedro (1991). La Reclamación de la Guayana Esequiba. Caracas.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - "Guyana: De Rupununi a La Haya". En El Tapete (in Spanish). 4 July 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

- Braveboy-Wagner, Jacqueline Anne (2019). The Venezuela-Guyana Border Dispute: Britain's Colonial Legacy In Latin America. Routledge. ISBN 9781000306897.

- González, Pedro (1991). La Reclamación de la Guayana Esequiba. Caracas. pp. 14, 45–47.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ishmael, Odeen (2013). The Trail of Diplomacy: The Guyana-Venezuela Border Issue. Odeen Ishmael. ISBN 9781493126552.

- Briceño Monzón, Claudio A.; Olivar, José Alberto; Buttó, Luis Alberto (2016). La Cuestión Esequibo: Memoria y Soberanía. Caracas, Venezuela: Universidad Metropolitana. p. 145.

- Milutin Tomanović (1971) Hronika međunarodnih događaja 1970, Institute of International Politics and Economics: Belgrade, p. 2512 (in Serbo-Croatian)

- "The Trail of Diplomacy". www.guyana.org. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- "Secretary-General Chooses International Court of Justice as Means for Peacefully Settling Long-Standing Guyana-Venezuela Border Controversy". UN. 30 January 2018.

- "Asamblea Nacional ratificó la soberanía de Venezuela sobre el Esequibo". El Nacional (in Spanish). 1 October 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Press Release in Response to Venezuela's Objection to Guyana's Submission to the CLCS". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Guyana. 15 March 2012.

- "Communication received with regard to the submission made by Guyana to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf" (PDF). UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). 9 March 2012.

- "Gov't protests after Venezuela holds oil research boat". Stabroek News. 12 October 2013.

- "Venezuela deplores incursion of vessel under Guyana's authorization". El Universal. 11 October 2013. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- "Venezuela frees seized US-operated ship Teknik Perdana". BBC. 15 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "Guyana says Exxon to begin offshore drilling, Venezuela irked". Reuters. 5 March 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "ExxonMobil Announces Significant Oil Discovery Offshore Guyana". ExxonMobil. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "Canciller guyanés convocará a embajadora venezolana". El Universal. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "Guyana suspende entrada de vuelos de la aerolínea venezolana Conviasa". El Universal. 7 June 2015. Archived from the original on 30 July 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- "Guyana wants ICJ to order Venezuela off Ankoko". The Guyana Chronicle. 6 April 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Guyana lleva a Venezuela a la Corte Internacional de Justicia de La Haya en la disputa por el territorio del Esequibo". BBC. 29 March 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- "Venezuela propone a Guyana reiniciar los contactos sobre la soberanía de la región del Esequibo". Europa Press (in Spanish). 30 March 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "El Esequibo, el territorio que disputan Venezuela y Guyana desde hace más de 50 años". BBC. 30 March 2018. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Guyana pedirá a la CIJ que falle a su favor en la reclamación fronteriza". EFE. 19 June 2018.

- "Guyana pedirá a la CIJ que falle a su favor en la disputa contra Venezuela". El Nacional. 19 June 2018.

- "Venezuela no participará en procedimiento sobre Esequibo promovido por Guyana en La Haya". Efecto Cocuyo. 18 June 2018. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018.

- "Arbitral Award of 3 October 1899 (Guyana v. Venezuela): Fixing of time-limits for the filing of written pleadings on the question of the jurisdiction of the Court" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 2 July 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Venezuela y Guayana deberán presentar sus alegatos sobre el Esequibo". El Nacional. 2 July 2018.

- "Guyana espera fallo vinculante de la Corte Internacional de Justicia en disputa por el Esequibo". El Nacional. 28 October 2019.

- "Guyana optimistic it will win the Esequibo dispute at the International Court of Justice". MercoPress. 7 December 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- "Venezuela geen deel in hoorzittingen grensgeschil". Star Nieuws (in Dutch). Retrieved 23 June 2020.

- "Guyana asks World Court to confirm border with Venezuela". Reuters. 30 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- "ARBITRAL AWARD OF 3 OCTOBER 1899 (GUYANA v. VENEZUELA)" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 8 December 2021.

- "U.S., Guyana to launch joint maritime patrols near disputed Venezuela border". news.yahoo.com. Reuters. 18 September 2020. Retrieved 19 September 2020.

- "El Gobierno venezolano y la oposición acuerdan defender la soberanía de Esequibo y luchar contra la pandemia". ElDiario.es (in Spanish). Mexico City. EFE. 7 September 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

References

- LaFeber, Walter. "The Background of Cleveland's Venezuelan Policy: A Reinterpretation." American Historical Review 66 (July 1961), pp. 947–967.

- Schoult, Lars. A History of U.S. Policy Toward Latin America Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- U.S. Department of State, Office of the Historian, "Venezuela Boundary Dispute, 1895–1899"