Indigenous peoples in Canada

Indigenous peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations,[2] Inuit,[3] and Métis.[4] Although Indian is a term still commonly used in legal documents, the descriptors Indian and Eskimo have fallen into disuse in Canada, and many consider them to be pejorative.[5][6][7] Aboriginal peoples as a collective noun[8] is a specific term of art used in some legal documents, including the Constitution Act, 1982, though in most Indigenous circles Aboriginal has also fallen into disfavour.[9][10]

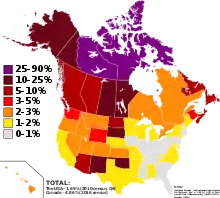

Indigenous peoples in Canada and the U.S., percent of population by area | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 1,807,250[1] 5.0% of the Canadian population (2021) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Ontario | 406,585 (2.9%) |

| British Columbia | 290,210 (5.9%) |

| Alberta | 284,470 (6.8%) |

| Manitoba | 237,185 (18.1%) |

| Quebec | 205,010 (2.5%) |

| Saskatchewan | 187,885 (17.0%) |

| Nova Scotia | 52,430 (5.5%) |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 46,545 (9.3%) |

| New Brunswick | 33,295 (4.4%) |

| Nunavut | 31,390 (85.8%) |

| Northwest Territories | 20,035 (49.6%) |

| Yukon | 8,810 (22.3%) |

| Prince Edward Island | 3,385 (2.2%) |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indigenous peoples in Canada |

|---|

.JPG.webp) |

|

|

Old Crow Flats and Bluefish Caves are some of the earliest known sites of human habitation in Canada. The Paleo-Indian Clovis, Plano, and Pre-Dorset cultures pre-date the current Indigenous peoples of the Americas. Projectile point tools, spears, pottery, bangles, chisels, and scrapers mark archaeological sites, thus distinguishing cultural periods, traditions, and lithic reduction styles.

The characteristics of Indigenous[nb 1] culture in Canada includes a long history of permanent settlements,[12] agriculture,[13] civic and ceremonial architecture,[14] complex societal hierarchies, and trading networks.[15] Métis of mixed ancestry originated in the mid-17th century when First Nations and Inuit people married European fur traders, primarily the French.[16] The Inuit had more limited interaction with European settlers during that early period.[17] Various laws, treaties, and legislation have been enacted between European immigrants and First Nations across Canada. Today, it is a common perception that Aboriginal peoples in Canada have the right to self-government to provide an opportunity to manage historical, cultural, political, health care and economic control aspects within First Nation's communities. However, some Canadian legislation may contradict this, for example the Indian act states 35 (3),[8]

As of the 2021 census, the Indigenous population totaled 1,807,250 people, or 5.0% of the national population, with 1,048,405 First Nations people, 624,220 Métis, and 70,540 Inuit.[1] 7.7% of the population under the age of 14 are of Indigenous descent.[18] There are over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands with distinctive cultures, languages, art, and music.[19][20] National Indigenous Peoples Day recognizes the cultures and contributions of Indigenous peoples to the history of Canada.[21] First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples of all backgrounds have become prominent figures and have served as role models in the Indigenous community and help to shape the Canadian cultural identity.[22]

Terminology

In Section 35 of the Constitution Act, 1982, "Aboriginal peoples of Canada" includes First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples.[23] Aboriginal peoples is a legal term encompassing all Indigenous peoples living in Canada.[24][25] Aboriginal peoples has begun to be considered outdated and is slowly being replaced by the term Indigenous peoples.[26] There is also an effort to recognize each Indigenous group as a distinct nation, much as there are distinct European, African, and Asian cultures in their respective places.[27]

First Nations (most often used in the plural) has come into general use since the 1970s replacing Indians and Indian bands in everyday vocabulary.[24][25] However, on reserves, First Nations is being supplanted by members of various nations referring to themselves by their group or ethnic identity. In conversation, this would be "I am Haida", or "we are Kwantlens", in recognition of their First Nations ethnicities.[28] Also coming into general use since the 1970s, First Peoples refers to all Indigenous groups, i.e. First Nations, Inuit, and Métis.[29][30][5]

Native

Notwithstanding Canada's location within the Americas, the term Native American is hardly ever used in Canada, in order to avoid any confusion due to the ambiguous meaning of the word "American". Therefore, the term is typically used only in reference to the Indigenous peoples within the boundaries of the present-day United States.[31] Native Canadians was often used in Canada to differentiate this American term until the 1980s.[32]

In contrast to the more-specific Aboriginal, one of the issues with the term native is its general applicability: in certain contexts, it could be used in reference to non-Indigenous peoples in regards to an individual place of origin/birth.[33] For instance, people who were born or grew up in Calgary may call themselves "Calgary natives", as in they are native to that city. With this in mind, even the term native American, as another example, may very well indicate someone who is native to America rather than a person who is ethnically Indigenous to the boundaries of the present-day United States. In this sense, native may encompass a broad range of populations and is therefore not recommended,[33] although it is not generally considered offensive.

Indian

The Indian Act (R.S.C., 1985, c. I-5) sets the legal term Indian, designating that "a person who pursuant to this Act is registered as an Indian or is entitled to be registered as an Indian."[34] Section 5 of the act states that a registry shall be maintained "in which shall be recorded the name of every person who is entitled to be registered as an Indian under this Act."[34] No other term is legally recognized for the purpose of registration and the term Indian specifically excludes reference to Inuit as per section 4 of the act.

Indian remains in place as the legal term used in the Canadian Constitution; however, its usage outside such situations can be considered offensive.[5]

Eskimo

The term Eskimo has pejorative connotations in Canada and Greenland. Indigenous peoples in those areas have replaced the term Eskimo with Inuit,[35][36] though the Yupik of Alaska and Siberia do not consider themselves Inuit, and ethnographers agree they are a distinct people.[7][36] They prefer the terminology Yupik, Yupiit, or Eskimo. The Yupik languages are linguistically distinct from the Inuit languages, but are related to each other.[7] Linguistic groups of Arctic people have no universal replacement term for Eskimo, inclusive of all Inuit and Yupik across the geographical area inhabited by them.[7]

Legal categories

Besides these ethnic descriptors, Aboriginal peoples are often divided into legal categories based on their relationship with the Crown (i.e. the state). Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the federal government (as opposed to the provinces) the sole responsibility for "Indians, and Lands reserved for the Indians." The government inherited treaty obligations from the British colonial authorities in Eastern Canada and signed treaties itself with First Nations in Western Canada (the Numbered Treaties). The Indian Act, passed by the federal Parliament in 1876, has long governed its interactions with all treaty and non-treaty peoples.

Members of First Nations bands who are subject to the Indian Act are compiled on a list called the Indian Register, and such people are designated as status Indians. Many non-treaty First Nations and all Inuit and Métis peoples are not subject to the Indian Act. However, two court cases have clarified that Inuit, Métis, and non-status First Nations people are all covered by the term Indians in the Constitution Act, 1867. The first was Re Eskimos (1939), covering the Inuit; the second was Daniels v. Canada (2013), which concerns Métis and non-status First Nations.[37]

History

Paleo-Indian period

According to archaeological and genetic evidence, North and South America were the last continents in the world with human habitation.[39] During the Wisconsin glaciation, 50,000–17,000 years ago, falling sea levels allowed people to move across the Bering land bridge that joined Siberia to northwest North America (Alaska).[40] Alaska was ice-free because of low snowfall, allowing a small population to exist. The Laurentide Ice Sheet covered most of Canada, blocking nomadic inhabitants and confining them to Alaska (East Beringia) for thousands of years.[41][42]

Aboriginal genetic studies suggest that the first inhabitants of the Americas share a single ancestral population, one that developed in isolation, conjectured to be Beringia.[43][44] The isolation of these peoples in Beringia might have lasted 10,000–20,000 years.[45][46][47] Around 16,500 years ago, the glaciers began melting, allowing people to move south and east into Canada and beyond.[48][49][50]

The first inhabitants of North America arrived in Canada at least 14,000 years ago.[51] It is believed the inhabitants entered the Americas pursuing Pleistocene mammals such as the giant beaver, steppe wisent, musk ox, mastodons, woolly mammoths and ancient reindeer (early caribou).[52] One route hypothesized is that people walked south by way of an ice-free corridor on the east side of the Rocky Mountains, and then fanned out across North America before continuing on to South America.[53] The other conjectured route is that they migrated, either on foot or using primitive boats, down the Pacific Coast to the tip of South America, and then crossed the Rockies and Andes.[54] Evidence of the latter has been covered by a sea level rise of hundreds of metres following the last ice age.[55][56]

The Old Crow Flats and basin was one of the areas in Canada untouched by glaciations during the Pleistocene Ice ages, thus it served as a pathway and refuge for ice age plants and animals.[57] The area holds evidence of early human habitation in Canada dating from about 12,000.[58] Fossils from the area include some never accounted for in North America, such as hyenas and large camels.[59] Bluefish Caves is an archaeological site in Yukon, Canada from which a specimen of apparently human-worked mammoth bone has been radiocarbon dated to 12,000 years ago.[58]

Clovis sites dated at 13,500 years ago were discovered in western North America during the 1930s. Clovis peoples were regarded as the first widespread Paleo-Indian inhabitants of the New World and ancestors to all Indigenous peoples in the Americas.[60] Archaeological discoveries in the past thirty years have brought forward other distinctive knapping cultures who occupied the Americas from the lower Great Plains to the shores of Chile.

Localized regional cultures developed from the time of the Younger Dryas cold climate period from 12,900 to 11,500 years ago.[61] The Folsom tradition are characterized by their use of Folsom points as projectile tips at archaeological sites. These tools assisted activities at kill sites that marked the slaughter and butchering of bison.[62]

The land bridge existed until 13,000–11,000 years ago, long after the oldest proven human settlements in the New World began.[63] Lower sea levels in the Queen Charlotte sound and Hecate Strait produced great grass lands called archipelago of Haida Gwaii.[64] Hunter-gatherers of the area left distinctive lithic technology tools and the remains of large butchered mammals, occupying the area from 13,000–9,000 years ago.[64] In July 1992, the Government of Canada officially designated X̱á:ytem (near Mission, British Columbia) as a National Historic Site, one of the first Indigenous spiritual sites in Canada to be formally recognized in this manner.[65]

The Plano cultures was a group of hunter-gatherer communities that occupied the Great Plains area of North America between 12,000 and 10,000 years ago.[66] The Paleo-Indians moved into new territory as it emerged from under the glaciers. Big game flourished in this new environment.[67] The Plano culture are characterized by a range of projectile point tools collectively called Plano points, which were used to hunt bison. Their diets also included pronghorn, elk, deer, raccoon and coyote.[66] At the beginning of the Archaic period, they began to adopt a sedentary approach to subsistence.[66] Sites in and around Belmont, Nova Scotia have evidence of Plano-Indians, indicating small seasonal hunting camps, perhaps re-visited over generations from around 11,000–10,000 years ago.[66] Seasonal large and smaller game fish and fowl were food and raw material sources. Adaptation to the harsh environment included tailored clothing and skin-covered tents on wooden frames.[66]

Archaic period

The North American climate stabilized by 8000 BCE (10,000 years ago); climatic conditions were very similar to today's.[68] This led to widespread migration, cultivation and later a dramatic rise in population all over the Americas.[68] Over the course of thousands of years, Indigenous peoples of the Americas domesticated, bred and cultivated a large array of plant species. These species now constitute 50–60% of all crops in cultivation worldwide.[69]

The vastness and variety of Canada's climates, ecology, vegetation, fauna, and landform separations have defined ancient peoples implicitly into cultural or linguistic divisions. Canada is surrounded north, east, and west with coastline and since the last ice age, Canada has consisted of distinct forest regions. Language contributes to the identity of a people by influencing social life ways and spiritual practices.[70] Aboriginal religions developed from anthropomorphism and animism philosophies.[71]

The placement of artifacts and materials within an Archaic burial site indicated social differentiation based upon status.[68] There is a continuous record of occupation of S'ólh Téméxw by Aboriginal people dating from the early Holocene period, 10,000–9,000 years ago.[72] Archaeological sites at Stave Lake, Coquitlam Lake, Fort Langley and region uncovered early period artifacts. These early inhabitants were highly mobile hunter-gatherers, consisting of about 20 to 50 members of an extended family.[72] The Na-Dene people occupied much of the land area of northwest and central North America starting around 8,000 BCE.[73] They were the earliest ancestors of the Athabaskan-speaking peoples, including the Navajo and Apache. They had villages with large multi-family dwellings, used seasonally during the summer, from which they hunted, fished and gathered food supplies for the winter.[74] The Wendat peoples settled into Southern Ontario along the Eramosa River around 8,000–7,000 BCE (10,000–9,000 years ago).[75] They were concentrated between Lake Simcoe and Georgian Bay. Wendat hunted caribou to survive on the glacier-covered land.[75] Many different First Nations cultures relied upon the buffalo starting by 6,000–5,000 BCE (8,000–7,000 years ago).[75] They hunted buffalo by herding migrating buffalo off cliffs. Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump, near Lethbridge, Alberta, is a hunting grounds that was in use for about 5,000 years.[75]

The west coast of Canada by 7,000–5000 BCE (9,000–7,000 years ago) saw various cultures who organized themselves around salmon fishing.[75] The Nuu-chah-nulth of Vancouver Island began whaling with advanced long spears at about this time.[75] The Maritime Archaic is one group of North America's Archaic culture of sea-mammal hunters in the subarctic. They prospered from approximately 7,000 BCE–1,500 BCE (9,000–3,500 years ago) along the Atlantic Coast of North America.[76] Their settlements included longhouses and boat-topped temporary or seasonal houses. They engaged in long-distance trade, using as currency white chert, a rock quarried from northern Labrador to Maine.[77] The Pre-Columbian culture, whose members were called Red Paint People, is indigenous to the New England and Atlantic Canada regions of North America. The culture flourished between 3,000 BCE – 1,000 BCE (5,000–3,000 years ago) and was named after their burial ceremonies, which used large quantities of red ochre to cover bodies and grave goods.[78]

The Arctic small tool tradition is a broad cultural entity that developed along the Alaska Peninsula, around Bristol Bay, and on the eastern shores of the Bering Strait around 2,500 BCE (4,500 years ago).[79] These Paleo-Arctic peoples had a highly distinctive toolkit of small blades (microblades) that were pointed at both ends and used as side- or end-barbs on arrows or spears made of other materials, such as bone or antler. Scrapers, engraving tools and adze blades were also included in their toolkits.[79] The Arctic small tool tradition branches off into two cultural variants, including the Pre-Dorset, and the Independence traditions. These two groups, ancestors of Thule people, were displaced by the Inuit by 1000 CE.[79]: 179–81

Post-Archaic periods

The Old Copper complex societies dating from 3,000 BCE – 500 BCE (5,000–2,500 years ago) are a manifestation of the Woodland Culture, and are pre-pottery in nature.[80] Evidence found in the northern Great Lakes regions indicates that they extracted copper from local glacial deposits and used it in its natural form to manufacture tools and implements.[80]

The Woodland cultural period dates from about 2,000 BCE – 1,000 CE, and has locales in Ontario, Quebec, and Maritime regions.[81] The introduction of pottery distinguishes the Woodland culture from the earlier Archaic stage inhabitants. Laurentian people of southern Ontario manufactured the oldest pottery excavated to date in Canada.[70] They created pointed-bottom beakers decorated by a cord marking technique that involved impressing tooth implements into wet clay. Woodland technology included items such as beaver incisor knives, bangles, and chisels. The population practising sedentary agricultural life ways continued to increase on a diet of squash, corn, and bean crops.[70]

The Hopewell tradition is an Aboriginal culture that flourished along American rivers from 300 BCE – 500 CE. At its greatest extent, the Hopewell Exchange System networked cultures and societies with the peoples on the Canadian shores of Lake Ontario. Canadian expression of the Hopewellian peoples encompasses the Point Peninsula, Saugeen, and Laurel complexes.[82][83][84]

First Nations

First Nations peoples had settled and established trade routes across what is now Canada by 500 BCE – 1,000 CE. Communities developed each with its own culture, customs, and character.[85] In the northwest were the Athapaskan, Slavey, Dogrib, Tutchone, and Tlingit. Along the Pacific coast were the Tsimshian; Haida; Salish; Kwakiutl; Heiltsuk; Nootka; Nisga'a; Senakw and Gitxsan. In the plains were the Niisitapi; Káínawa; Tsuutʼina; and Piikáni. In the northern woodlands were the Nēhiyawak and Chipewyan. Around the Great Lakes were the Anishinaabe; Algonquin; Haudenosaunee and Wendat. Along the Atlantic coast were the Beothuk, Wəlastəkwewiyik, Innu, Abenaki and Mi'kmaq.

Many First Nations civilizations[86] established characteristics and hallmarks that included permanent urban settlements or cities,[87] agriculture, civic and monumental architecture, and complex societal hierarchies.[88] These cultures had evolved and changed by the time of the first permanent European arrivals (c. late 15th–early 16th centuries), and have been brought forward through archaeological investigations.[89]

There are indications of contact made before Christopher Columbus between the first peoples and those from other continents. Aboriginal people in Canada first interacted with Europeans around 1000 CE, but prolonged contact came after Europeans established permanent settlements in the 17th and 18th centuries.[90] European written accounts generally recorded friendliness of the First Nations, who profited in trade with Europeans.[90] Such trade generally strengthened the more organized political entities such as the Iroquois Confederation.[91] Throughout the 16th century, European fleets made almost annual visits to the eastern shores of Canada to cultivate the fishing opportunities. A sideline industry emerged in the un-organized traffic of furs overseen by the Indian Department.[92]

Prominent First Nations people include Joe Capilano, who met with King of the United Kingdom, Edward VII, to speak of the need to settle land claims and Ovide Mercredi, a leader at both the Meech Lake Accord constitutional reform discussions and Oka Crisis.[93][94]

Inuit

Inuit are the descendants of what anthropologists call the Thule culture, which emerged from western Alaska around 1,000 CE and spread eastward across the Arctic, displacing the Dorset culture (in Inuktitut, the Tuniit). Inuit historically referred to the Tuniit as "giants", who were taller and stronger than the Inuit.[95] Researchers hypothesize that the Dorset culture lacked dogs, larger weapons and other technologies used by the expanding Inuit society.[96] By 1300, the Inuit had settled in west Greenland, and finally moved into east Greenland over the following century. The Inuit had trade routes with more southern cultures. Boundary disputes were common and led to aggressive actions.[17]

Warfare was common among Inuit groups with sufficient population density. Inuit, such as the Nunatamiut (Uummarmiut) who inhabited the Mackenzie River delta area, often engaged in common warfare. The Central Arctic Inuit lacked the population density to engage in warfare. In the 13th century, the Thule culture began arriving in Greenland from what is now Canada. Norse accounts are scant. Norse-made items from Inuit campsites in Greenland were obtained by either trade or plunder.[97] One account, Ívar Bárðarson, speaks of "small people" with whom the Norsemen fought.[98] 14th-century accounts relate that a western settlement, one of the two Norse settlements, was taken over by the Skræling.[99]

After the disappearance of the Norse colonies in Greenland, the Inuit had no contact with Europeans for at least a century. By the mid-16th century, Basque fishers were already working the Labrador coast and had established whaling stations on land, such as those excavated at Red Bay.[100] The Inuit appear not to have interfered with their operations, but they did raid the stations in winter for tools, and particularly worked iron, which they adapted to native needs.[101]

Notable among the Inuit are Abraham Ulrikab and family who became a zoo exhibit in Hamburg, Germany, and Tanya Tagaq, a traditional throat singer.[102] Abe Okpik was instrumental in helping Inuit obtain surnames rather than disc numbers and Kiviaq (David Ward) won the legal right to use his single-word Inuktituk name.[103][104]

Métis

The Métis are people descended from marriages between Europeans (mainly French)[105] and Cree, Ojibway, Algonquin, Saulteaux, Menominee, Mi'kmaq, Maliseet, and other First Nations.[16] Their history dates to the mid-17th century.[2] When Europeans first arrived to Canada they relied on Aboriginal peoples for fur trading skills and survival. To ensure alliances, relationships between European fur traders and Aboriginal women were often consolidated through marriage.[106] The Métis homeland consists of the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and Ontario, as well as the Northwest Territories (NWT).[107]

Amongst notable Métis people are singer and actor Tom Jackson,[108] Commissioner of the Northwest Territories Tony Whitford, and Louis Riel who led two resistance movements: the Red River Rebellion of 1869–1870 and the North-West Rebellion of 1885, which ended in his trial and subsequent execution.[109][110][111]

The languages inherently Métis are either Métis French or a mixed language called Michif. Michif, Mechif or Métchif is a phonetic spelling of Métif, a variant of Métis.[112] The Métis today predominantly speak English, with French a strong second language, as well as numerous Aboriginal tongues. A 19th-century community of the Métis people, the Anglo-Métis, were referred to as Countryborn. They were children of Rupert's Land fur trade typically of Orcadian, Scottish, or English paternal descent and Aboriginal maternal descent.[113] Their first languages would have been Aboriginal (Cree, Saulteaux, Assiniboine, etc.) and English. Their fathers spoke Gaelic, thus leading to the development of an English dialect referred to as "Bungee".[114]

S.35 of the Constitution Act, 1982 mentions the Métis yet there has long been debate over legally defining the term Métis,[115] but on September 23, 2003, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Métis are a distinct people with significant rights (Powley ruling).[116]

Unlike First Nations people, there has been no distinction between status and non-status Métis;[117] the Métis, their heritage and Aboriginal ancestry have often been absorbed and assimilated into their surrounding populations.[118]

Forced assimilation

From the late 18th century, European Canadians (and the Canadian government) encouraged assimilation of Aboriginal culture into what was referred to as "Canadian culture."[119][120] These attempts reached a climax in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with a series of initiatives that aimed at complete assimilation and subjugation of the Aboriginal peoples. These policies, which were made possible by legislation such as the Gradual Civilization Act[121] and the Indian Act,[122] focused on European ideals of Christianity, sedentary living, agriculture, and education.

Christianization

.jpg.webp)

Missionary work directed at the Aboriginal people of Canada had been ongoing since the first missionaries arrived in the 1600s, generally from France, some of whom were martyred (Jesuit saints called the Canadian Martyrs). Christianization as government policy became more systematic with the Indian Act in 1876, which would bring new sanctions for those who did not convert to Christianity. For example, the new laws would prevent non-Christian Aboriginal people from testifying or having their cases heard in court, and ban alcohol consumption.[123] When the Indian Act was amended in 1884, traditional religious and social practices, such as the Potlatch, would be banned, and further amendments in 1920 would prevent "status Indians" (as defined in the Act) from wearing traditional dress or performing traditional dances in an attempt to stop all non-Christian practices.[123]

Sedentary living, reserves, and 'gradual civilization'

Another focus of the Canadian government was to make the Aboriginal groups of Canada sedentary, as they thought that this would make them easier to assimilate. In the 19th century, the government began to support the creation of model farming villages, which were meant to encourage non-sedentary Aboriginal groups to settle in an area and begin to cultivate agriculture.[124] When most of these model farming villages failed,[124] the government turned instead to the creation of Indian reserves with the Indian Act of 1876.[122] With the creation of these reserves came many restricting laws, such as further bans on all intoxicants, restrictions on eligibility to vote in band elections, decreased hunting and fishing areas, and inability for status Indians to visit other groups on their reservations.[122] Farming was still seen as an important practice for assimilation on reserves; however, by the late 19th century the government had instituted restrictive policies here too, such as the Peasant Farm Policy, which restricted reserve farmers largely to the use of hand tools.[125] This was implemented largely to limit the competitiveness of First Nations farming.[126]

Through the Gradual Civilization Act in 1857, the government would encourage Indians (i.e., First Nations) to enfranchise – to remove all legal distinctions between [Indians] and Her Majesty's other Canadian Subjects.[121] If an Aboriginal chose to enfranchise, it would strip them and their family of Aboriginal title, with the idea that they would become "less savage" and "more civilized," thus become assimilated into Canadian society.[127] However, they were often still defined as non-citizens by Europeans, and those few who did enfranchise were often met with disappointment.[127]

Residential system

The final government strategy of assimilation, made possible by the Indian Act was the Canadian residential school system:

Of all the initiatives that were undertaken in the first century of Confederation, none was more ambitious or central to the civilizing strategy of the Department, to its goal of assimilation than the residential school system… it was the residential school experience that would lead children most effectively out of their "savage" communities into "higher civilization" and "full citizenship."[128]

Beginning in 1847 and lasting until 1996, the Canadian government, in partnership with the dominant Christian Churches, ran 130 residential boarding schools across Canada for Aboriginal children, who were forcibly taken from their homes.[129] While the schools provided some education, they were plagued by under-funding, disease, and abuse.[130]

According to some scholars, the Canadian government's laws and policies, including the residential school system, that encouraged or required Indigenous peoples to assimilate into a Eurocentric society, violated the United Nations Genocide Convention that Canada signed in 1949 and passed through Parliament in 1952. Therefore, these scholars believe that Canada could be tried in international court for genocide.[131] A legal case resulted in settlement of CA$2 billion in 2006 and the 2008 establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which confirmed the injurious effect on children of this system and turmoil created between Indigenous peoples and non-Indigenous peoples.[132] In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper issued an apology on behalf of the Canadian government and its citizens for the residential school system.[133]

Politics, law, and legislation

Indigenous law vs. Aboriginal law

Canadian Indigenous law refers to Indigenous peoples' own legal systems. This includes the laws and legal processes developed by Indigenous groups to govern their relationships, manage their natural resources, and manage conflicts.[134] Indigenous law is developed from a variety of sources and institutions, which differ across legal traditions.[135] Canadian aboriginal law is the area of law related to the Canadian Government's relationship with its Indigenous peoples. Section 91(24) of the Constitution Act, 1867 gives the federal parliament exclusive power to legislate in matters related to Aboriginals, which includes groups governed by the Indian Act, different Numbered Treaties and outside of those Acts.[136]

Treaties

The Canadian Crown and Indigenous peoples began interactions during the European colonization period. Many agreements signed before the Confederation of Canada are recognized in Canadian law, such as the Peace and Friendship Treaties, the Robinson Treaties, the Douglas Treaties, and many others. After Canada's acquisition of Rupert's Land and the North-Western Territory in 1870, the eleven Numbered treaties were signed between First Nations and the Crown from 1871 to 1921. These treaties are agreements with the Crown administered by Canadian Aboriginal law and overseen by the Minister of Crown–Indigenous Relations.[137]

In 1973, Canada re-started signing new treaties and agreements with Indigenous peoples to address their land claims. The first modern treaty implemented under the new framework was the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement in 1970. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement of 1993 lead to the creation of the Inuit-majority territory of Nunavut later that decade. The Canadian Crown continues to sign new treaties with Indigenous peoples, notably though the British Columbia Treaty Process.[138]

According to the First Nations–Federal Crown Political Accord, "cooperation will be a cornerstone for partnership between Canada and First Nations, wherein Canada is the short-form reference to Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada.[29] The Supreme Court of Canada argued that treaties "served to reconcile pre-existing Aboriginal sovereignty with assumed Crown sovereignty, and to define Aboriginal rights."[29] First Nations interpreted agreements covered in treaty 8 to last "as long as the sun shines, grass grows and rivers flow."[139] However, the Canadian government has frequently breached the Crown's treaty obligations over the years, and tries to address these issues by negotiating specific land claim.[140]

Indian Act

The Indian Act is federal legislation that dates from 1876. There have been over 20 major changes made to the act since then, the last time being in 1951; amended in 1985 with Bill C-31. The Indian Act indicates how reserves and bands can operate and defines who is recognized as an "Indian."[141]

In 1985, the Canadian Parliament passed Bill C-31, An Act to Amend the Indian Act. Because of a constitutional requirement, the bill took effect on 17 April 1985.[142]

- It ends discriminatory provisions of the Indian Act, especially those that discriminated against women.[142]

- It changes the meaning of status and for the first time allows for limited reinstatement of Indians who were denied or lost status or band membership.[142]

- It allows bands to define their own membership rules.[142]

Those people accepted into band membership under band rules may not be status Indians. C-31 clarified that various sections of the Indian Act apply to band members. The sections under debate concern community life and land holdings. Sections pertaining to Indians (First Nations peoples) as individuals (in this case, wills and taxation of personal property) were not included.[142]

Royal Commission

_without_captions.svg.png.webp)

The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was a Royal Commission undertaken by the Government of Canada in 1991 to address issues of the Aboriginal peoples of Canada.[143] It assessed past government policies toward Aboriginal people, such as residential schools, and provided policy recommendations to the government.[144] The Commission issued its final report in November 1996. The five-volume, 4,000-page report covered a vast range of issues; its 440 recommendations called for sweeping changes to the interaction between Aboriginal, non-Aboriginal people and the governments in Canada.[143] The report "set out a 20-year agenda for change."[145]

Health policy

In 1995, the Government of Canada announced the Aboriginal Right to Self-Government Policy.[146] This policy recognizes that First Nations and Inuit have the constitutional right to shape their own forms of government to suit their particular historical, cultural, political and economic circumstances. The Indian Health Transfer Policy provided a framework for the assumption of control of health services by Aboriginal peoples, and set forth a developmental approach to transfer centred on self-determination in health.[147][148] Through this process, the decision to enter transfer discussions with Health Canada rests with each community. Once involved in transfer, communities can take control of health programme responsibilities at a pace determined by their individual circumstances and health management capabilities.[149] The National Aboriginal Health Organization (NAHO) incorporated in 2000, was an Aboriginal-designed and-controlled not-for-profit body in Canada that worked to influence and advance the health and well-being of Aboriginal Peoples.[150] Its funding was discontinued in 2012.

Political organization

First Nations and Inuit organizations ranged in size from band societies of a few people to multi-nation confederacies like the Iroquois. First Nations leaders from across the country formed the Assembly of First Nations, which began as the National Indian Brotherhood in 1968.[151] The Métis and the Inuit are represented nationally by the Métis National Council and Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami respectively.

Today's political organizations have resulted from interaction with European-style methods of government through the Federal Interlocutor for Métis and Non-Status Indians. Indigenous political organizations throughout Canada vary in political standing, viewpoints, and reasons for forming.[152] First Nations, Métis and Inuit negotiate with the Government of Canada through Indian and Northern Affairs Canada in all affairs concerning land, entitlement, and rights.[151] The First Nation groups that operate independently do not belong to these groups.[151]

Culture

Countless Indigenous words, inventions and games have become an everyday part of Canadian language and use. The canoe, snowshoes, the toboggan, lacrosse, tug of war, maple syrup and tobacco are just a few of the products, inventions and games.[153] Some of the words include the barbecue, caribou, chipmunk, woodchuck, hammock, skunk, and moose.[154]

Many places in Canada, both natural features and human habitations, use Indigenous names. The word Canada itself derives from the St. Lawrence Iroquoian word meaning 'village' or 'settlement'.[155] The province of Saskatchewan derives its name from the Saskatchewan River, which in the Cree language is called Kisiskatchewani Sipi, meaning 'swift-flowing river'.[156] Ottawa, the name of Canada's capital city, comes from the Algonquin language term adawe, meaning 'to trade'.[156]

Modern youth groups, such as Scouts Canada and the Girl Guides of Canada, include programs based largely on Indigenous lore, arts and crafts, character building and outdoor camp craft and living.[157]

Aboriginal cultural areas depend upon their ancestors' primary lifeway, or occupation, at the time of European contact. These culture areas correspond closely with physical and ecological regions of Canada.[158] The Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast were centred around ocean and river fishing; in the interior of British Columbia, hunter-gatherer and river fishing. In both of these areas, the salmon was of chief importance. For the people of the plains, bison hunting was the primary activity. In the subarctic forest, other species such as the moose were more important. For peoples near the Great Lakes and Saint Lawrence River, shifting agriculture was practised, including the raising of maize, beans, and squash.[20][158] While for the Inuit, hunting was the primary source of food with seals the primary component of their diet.[159] The caribou, fish, other marine mammals and to a lesser extent plants, berries and seaweed are part of the Inuit diet. One of the most noticeable symbols of Inuit culture, the inuksuk is the emblem of the Vancouver 2010 Winter Olympics. Inuksuit are rock sculptures made by stacking stones; in the shape of a human figure, they are called inunnguaq.[160]

Indian reserves, established in Canadian law by treaties such as Treaty 7, are lands of First Nations recognized by non-Indigenous governments.[161] Some reserves are within cities, such as the Opawikoscikan Reserve in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, Wendake in Quebec City or Enoch Cree Nation 135 in the Edmonton Metropolitan Region. There are more reserves in Canada than there are First Nations, which were ceded multiple reserves by treaty.[162] Aboriginal people currently work in a variety of occupations and may live outside their ancestral homes. The traditional cultures of their ancestors, shaped by nature, still exert a strong influence on them, from spirituality to political attitudes.[20][158] National Indigenous Peoples Day is a day of recognition of the cultures and contributions of the First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples of Canada. The day was first celebrated in 1996, after it was proclaimed that year, by then Governor General of Canada Roméo LeBlanc, to be celebrated on June 21 annually.[21] Most provincial jurisdictions do not recognize it as a statutory holiday.[21]

Languages

There are 13 Aboriginal language groups, 11 oral and 2 sign, in Canada, made up of more than 65 distinct dialects.[163] Of these, only Cree, Inuktitut, and Ojibwe have a large enough population of fluent speakers to be considered viable to survive in the long term.[164] Two of Canada's territories give official status to native languages. In Nunavut, Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun are official languages alongside the national languages of English and French, and Inuktitut is a common vehicular language in territorial government.[165]

In the Northwest Territories, the Official Languages Act declares that there are 11 different languages: Chipewyan, Cree, English, French, Gwichʼin, Inuinnaqtun, Inuktitut, Inuvialuktun, North Slavey, South Slavey, and Tłįchǫ.[166] Besides English and French, these languages are not vehicular in government; official status entitles citizens to receive services in them on request and to deal with the government in them.[164]

| Aboriginal language | No. of speakers | Mother tongue | Home language |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cree | 99,950 | 78,855 | 47,190 |

| Inuktitut | 35,690 | 32,010 | 25,290 |

| Ojibway | 32,460 | 11,115 | 11,115 |

| Montagnais-Naskapi (Innu) | 11,815 | 10,970 | 9,720 |

| Dene | 11,130 | 9,750 | 7,490 |

| Oji-Cree (Anihshininiimowin) | 12,605 | 8,480 | 8,480 |

| Mi'kmaq | 8,750 | 7,365 | 3,985 |

| Siouan languages (Dakota/Sioux) | 6,495 | 5,585 | 3,780 |

| Atikamekw | 5,645 | 5,245 | 4,745 |

| Blackfoot | 4,915 | 3,085 | 3,085 |

| For a complete list see: Spoken languages of Canada | |||

Visual art

Indigenous peoples were producing art for thousands of years before the arrival of European settler colonists and the eventual establishment of Canada as a nation state. Like the peoples who produced them, Indigenous art traditions spanned territories across North America. Indigenous art traditions are organized by art historians according to cultural, linguistic or regional groups: Northwest Coast, Plateau, Plains, Eastern Woodlands, Subarctic, and Arctic.[167]

Art traditions vary enormously amongst and within these diverse groups. Indigenous art with a focus on portability and the body is distinguished from European traditions and its focus on architecture. Indigenous visual art may be used in conjunction with other arts. Shamans' masks and rattles are used ceremoniously in dance, storytelling and music.[167] Artworks preserved in museum collections date from the period after European contact and show evidence of the creative adoption and adaptation of European trade goods such as metal and glass beads.[168] The distinct Métis cultures that have arisen from inter-cultural relationships with Europeans contribute culturally hybrid art forms.[169] During the 19th and the first half of the 20th century the Canadian government pursued an active policy of forced and cultural assimilation toward Indigenous peoples. The Indian Act banned manifestations of the Sun Dance, the Potlatch, and works of art depicting them.[170]

It was not until the 1950s and 1960s that Indigenous artists such as Mungo Martin, Bill Reid and Norval Morrisseau began to publicly renew and re-invent Indigenous art traditions. Currently, there are Indigenous artists practising in all media in Canada and two Indigenous artists, Edward Poitras and Rebecca Belmore, have represented Canada at the Venice Biennale in 1995 and 2005 respectively.[167]

Music

The Aboriginal peoples of Canada encompass diverse ethnic groups with their individual musical traditions. Music is usually social (public) or ceremonial (private). Public, social music may be dance music accompanied by rattles and drums. Private, ceremonial music includes vocal songs with accompaniment on percussion, used to mark occasions like Midewivin ceremonies and Sun Dances.

Traditionally, Indigenous peoples used the materials at hand to make their instruments for centuries before Europeans immigrated to Canada.[171] First Nations people made gourds and animal horns into rattles, which were elaborately carved and brightly painted.[172] In woodland areas, they made horns of birch bark and drumsticks of carved antlers and wood. Traditional percussion instruments such as drums were generally made of carved wood and animal hides. These musical instruments provide the background for songs, and songs the background for dances. Traditional First Nations people consider song and dance to be sacred. For years after Europeans came to Canada, First Nations people were forbidden to practice their ceremonies.[170][171]

Demography

There are three (First Nations,[2] Inuit[3] and Métis[4]) distinctive groups of Indigenous peoples that are recognized in the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982, sections 25 and 35.[23] Under the Employment Equity Act, Aboriginal people are a designated group along with women, visible minorities, and persons with disabilities;[173] as such, they are neither a visible minority under the Act or in the view of Statistics Canada.[174]

The 2016 Canadian Census enumerated 1,673,780 Aboriginal people in Canada, 4.9% of the country's total population.[175] This total includes 977,230 First Nations people, 587,545 Métis, and 65,025 Inuit. National representative bodies of Aboriginal people in Canada include the Assembly of First Nations, the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, the Métis National Council, the Native Women's Association of Canada, the National Association of Native Friendship Centres, and the Congress of Aboriginal Peoples.[176]

In 2016, Indigenous children ages zero to four accounted for 7.7% of those aged zero to four in Canada, and made up 51.2% of children in this age group living in foster care.[177]

In the 20th century the Aboriginal population of Canada increased tenfold.[178] Between 1900 and 1950 the population grew by 29%. After the 1960s the infant mortality level on reserves dropped dramatically and the population grew by 161%.[179][180] Since the 1980s the number of First Nations babies more than doubled and currently almost half of the First Nations population is under the age of 25.[178][180]

Indigenous people assert that their sovereign rights are valid, and point to the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which is mentioned in the Canadian Constitution Act, 1982, Section 25, the British North America Acts and the 1969 Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (to which Canada is a signatory) in support of this claim.[181][182]

Provinces & territories

| Province / Territory | Number | %[lower-alpha 1] | First Nations (Indian) |

Métis | Inuit | Multiple | Other[lower-alpha 2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Columbia | 270,585 | 5.9% | 172,520 | 89,405 | 1,615 | 4,350 | 2,695 | |

| Alberta | 258,640 | 6.5% | 136,590 | 114,370 | 2,500 | 2,905 | 2,280 | |

| Saskatchewan | 175,020 | 16.3% | 114,565 | 57,875 | 360 | 1,305 | 905 | |

| Manitoba | 223,310 | 18.0% | 130,505 | 89,360 | 605 | 2,020 | 820 | |

| Ontario | 374,395 | 2.8% | 236,685 | 120,585 | 3,860 | 5,725 | 7,540 | |

| Quebec | 182,890 | 2.3% | 92,650 | 69,360 | 13,940 | 2,760 | 4,170 | |

| New Brunswick | 29,385 | 4.0% | 17,570 | 10,205 | 385 | 470 | 750 | |

| Nova Scotia | 51,490 | 5.7% | 25,830 | 23,315 | 795 | 835 | 720 | |

| Prince Edward Island | 2,740 | 2.0% | 1,870 | 710 | 75 | 20 | 65 | |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 45,725 | 8.9% | 28,370 | 7,790 | 6,450 | 560 | 2,560 | |

| Yukon | 8,195 | 23.3% | 6,690 | 1,015 | 225 | 160 | 105 | |

| Northwest Territories | 20,860 | 50.7% | 13,180 | 3,390 | 4,080 | 155 | 55 | |

| Nunavut | 30,550 | 85.9% | 190 | 165 | 30,140 | 55 | 10 | |

| Canada | 1,673,780 | 4.9% | 977,230 | 587,545 | 65,025 | 21,310 | 22,670 | |

Source: 2016 Census[183]

| ||||||||

Ethnographers commonly classify Indigenous peoples of the Americas in the United States and Canada into ten geographical regions, cultural areas, with shared cultural traits.[184] The Canadian regions are:

- Arctic cultural area (Eskimo–Aleut languages)

- Subarctic culture area (Na-Dene languages and Algic languages)

- Eastern Woodlands (Northeast) cultural area (Algic languages and Iroquoian languages)

- Plains cultural area (Siouan–Catawban languages)

- Northwest Plateau cultural area (Salishan languages)

- Northwest Coast cultural area (Penutian languages, Tsimshianic languages and Wakashan languages)

Urban population

Across Canada, 56% of Indigenous peoples live in urban areas. The urban Indigenous population is the fastest-growing population segment in Canada.[185]

| City | Urban Indigenous population | Percent of population |

|---|---|---|

| Winnipeg | 92,810 | 12.2% |

| Edmonton | 76,205 | 5.9% |

| Vancouver | 61,455 | 2.5% |

| Toronto | 46,315 | 0.8% |

| Calgary | 41,645 | 3.0% |

| Ottawa-Gatineau | 38,115 | 2.9% |

| Montreal | 34,745 | 0.9% |

| Saskatoon | 31,350 | 10.9% |

| Regina | 21,650 | 9.3% |

| Victoria | 17,245 | 4.8% |

| Prince Albert | 16,830 | 39.7% |

| Halifax | 15,815 | 4.0% |

| Sudbury | 15,695 | 9.7% |

| Thunder Bay | 15,075 | 12.7% |

See also

Notes

- Indigenous has been capitalized in keeping with the style guide of the Government of Canada.[11] The capitalization also aligns with the style used within the final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In the Canadian context, Indigenous is capitalized when discussing peoples, beliefs or communities in the same way European or Canadian is used to refer to non-Indigenous topics or people.[9]

References

- Government of Canada, Statistics Canada (September 21, 2022). "Indigenous identity by Registered or Treaty Indian status: Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations with parts". www12.statcan.gc.ca. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- "Civilization.ca-Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage-Culture". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. Government of Canada. May 12, 2006. Archived from the original on October 20, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- "Inuit Circumpolar Council (Canada)-ICC Charter". Inuit Circumpolar Council > ICC Charter and By-laws > ICC Charter. 2007. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- Todd, Thornton & Collins 2001, p. 10.

- "Terminology of First Nations, Native, Aboriginal and Métis" (PDF). Aboriginal Infant Development Programs of B.C. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2010. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- "Words First An Evolving Terminology Relating to Indigenous peoples in Canada". Communications Branch of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. 2004. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- Olson & Pappas 1994, p. 213.

- "Indigenous or Aboriginal: Which is correct?". September 21, 2016. Archived from the original on September 22, 2016. Retrieved November 19, 2020.

- McKay, Celeste (April 2015). "Briefing Note on Terminology". University of Manitoba. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- "Native American, First Nations or Aboriginal? | Druide". druide.com. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- "14.12 Elimination of Racial and Ethnic Stereotyping, Identification of Groups". Translation Bureau. Public Works and Government Services Canada. 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2020.

- Darnell, Regna (2001). Invisible genealogies: a history of Americanist anthropology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-1710-2. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- Cameron, Rondo E (1993). A concise economic history of the world: from Paleolithic times to the present. Oxford University Press. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-19-507445-1. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- Kalman, Harold; Mills, Edward (September 30, 2007). "Architectural History: Early First Nations". The Canadian Encyclopedia (Historica-Dominion). Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Macklem, Patrick (2001). Indigenous difference and the Constitution of Canada. University of Toronto Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8020-4195-1. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- "What to Search: Topics-Canadian Genealogy Centre-Library and Archives Canada". Ethno-Cultural and Aboriginal Groups. Government of Canada. May 27, 2009. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- "Innu Culture 3. Innu-Inuit 'Warfare'". Adrian Tanner Department of Anthropology-Memorial University of Newfoundland. 1999. Archived from the original on August 23, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- [Indigenous peoples in Canada: Key results from the 2016 Census]

- 2011 National Household Survey: Indigenous Peoples in Canada: First Nations People, Métis and Inuit

- "Civilization.ca-Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage-object". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. May 12, 2006. Archived from the original on October 15, 2009. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- "National Aboriginal Day History" (PDF). Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- "National Aboriginal Achievement Award Recipients". National Aboriginal Achievement Foundation. Archived from the original on October 11, 2009. Retrieved October 7, 2009.

- "Constitution Act, 1982 Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms". Department of Justice. Government of Canada. 1982. Archived from the original on October 21, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- "Terminology of First Nations, Native, Aboriginal and Metis (NAHO)" (PDF). aidp.bc.ca/. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 14, 2010. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- "Terminology". Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- Todorova, Miglena (2016). "Co-Created Learning: Decolonizing Journalism Education in Canada". Canadian Journal of Communication. 41 (4): 673–92. doi:10.22230/cjc.2016v41n4a2970.

- "University Of Guelph Brand Guide | Indigenous Peoples". guides.uoguelph.ca. November 14, 2019. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- Edwards, John (2009). Language and Identity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-69602-9.

- Assembly of First Nations; Elizabeth II (2004). The Indian Act of Canada – Origins: Legislation Concerning Canada's First Peoples. 1. Ottawa: Assembly of First Nations. p. 3. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- "Words First An Evolving Terminology Relating to Aboriginal Peoples in Canada". Communications Branch of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. 2004. Archived from the original on January 6, 2003. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- "Native American". Oxford Advanced American Dictionary. Archived from the original on November 22, 2012. Retrieved May 27, 2013.

In Canada, the term Native American is not used, and the most usual way to refer to the Aboriginal peoples of Canada, other than the Inuit and Métis, is First Nations.

- "Origins of Canada's First Peoples". firstpeoplesofcanada.com. Retrieved March 25, 2021.

- "Terminology". Indigenous Foundations. First Nations & Indigenous Studies, University of British Columbia. 2009.

- Branch, Legislative Services. "Consolidated federal laws of canada, Indian Act". laws-lois.justice.gc.ca. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Hirschfelder, Arlene B; Beamer, Yvonne (2002). Native Americans today: resources and activities for educators, grades 4–8. Teacher Ideas Press, 2000. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-56308-694-6. Retrieved January 11, 2015.

- ""Eskimo" vs. "Inuit"". Expansionist Party of the United States. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- "Court rules Metis, non-status Indians qualify as 'Indians' under Act". CTV News. January 8, 2013. Archived from the original on January 8, 2013. Retrieved November 23, 2016.

- Burenhult, Göran (2000). Die ersten Menschen. Weltbild Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8289-0741-6.

- "Atlas of the Human Journey-The Genographic Project". National Geographic Society. 1996–2008. Archived from the original on May 1, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- Goebel T, Waters MR, O'Rourke DH (2008). "The Late Pleistocene Dispersal of Modern Humans in the Americas" (PDF). Science. 319 (5869): 1497–502. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1497G. doi:10.1126/science.1153569. PMID 18339930. S2CID 36149744.

- Wade, Nicholas (March 13, 2014). "Pause Is Seen in a Continent's Peopling". The New York Times.

- Pielou, E.C. (1991). After the Ice Age: The Return of Life to Glaciated North America. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-66812-3.

- Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man – A Genetic Odyssey. Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 978-0-8129-7146-0.

- Lewis, Cecil M. (February 2010). "Hierarchical modeling of genome-wide Short Tandem Repeat (STR) markers infers native American prehistory". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 141 (2): 281–289. doi:10.1002/ajpa.21143. PMID 19672848.

- Than, Ker (2008). "New World Settlers Took 20,000-Year Pit Stop". National Geographic Society. Retrieved January 23, 2010.

- Sigurðardóttir, Sigrún; Helgason, Agnar; Gulcher, Jeffrey R.; Stefansson, Kári; Donnelly, Peter (May 2000). "The Mutation Rate in the Human mtDNA Control Region". American Journal of Human Genetics. 66 (5): 1599–1609. doi:10.1086/302902. PMC 1378010. PMID 10756141.

- "First Americans Endured 20,000-Year Layover – Jennifer Viegas, Discovery News". Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved November 18, 2009.

Archaeological evidence, in fact, recognizes that people started to leave Beringia for the New World around 40,000 years ago, but rapid expansion into North America didn't occur until about 15,000 years ago, when the ice had literally broken

page 2 Archived March 13, 2012, at the Wayback Machine - Tamm, Erika; Kivisild, Toomas; Reidla, Maere; et al. (September 5, 2007). "Beringian Standstill and Spread of Native American Founders". PLoS ONE. 2 (9): e829. Bibcode:2007PLoSO...2..829T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000829. PMC 1952074. PMID 17786201.

- Dyke, A.S.; Moore, A.; Robertson, L. (2003). "Deglaciation of North America". Geological Survey of Canada Open File, 1574. Archived from the original on February 16, 2012. (Thirty-two digital maps at 1:7 000 000 scale with accompanying digital chronological database and one poster (two sheets) with full map series.

- Jordan, David K (2009). "Prehistoric Beringia". University of California-San Diego. Archived from the original on February 12, 2014. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- Fagan, Brian M.; Durrani, Nadia (2016). World Prehistory: A Brief Introduction. Routledge. p. 124. ISBN 978-1-317-34244-1.

- Meltzer, David J. (2009). "Chapter 2: The Landscape of Colonization: Glaciers, Climates, and the Environments of Ice Age North America". First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520250529.

- Merchant, Carolyn (2007). American environmental history: an introduction. Columbia University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-231-14034-8.

- Fladmark, K. R. (January 1979). "Alternate Migration Corridors for Early Man in North America". American Antiquity. 44 (1): 55–69. doi:10.2307/279189. JSTOR 279189. S2CID 162243347.

- "68 Responses to Sea will rise 'to levels of last Ice Age'". Center for Climate Systems Research, Columbia University. January 26, 2009. Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2009 – via realclimate.org.

- Harris, Ann G.; Tuttle, Esther; Tuttle, Sherwood D. (2004). Geology of National Parks. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-7872-9970-5.

- "Life in Crow Flats-Part 1". Old Crow's official Website. Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation. 1998–2009. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- Cordell, Linda S.; Lightfoot, Kent; McManamon, Francis; Milner, George (2008). Archaeology in America: An Encyclopedia. Vol. 4. ABC-CLIO. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-313-02189-3.

- "Old Crow Flats". taiga.net. Archived from the original on August 23, 2007. Retrieved August 5, 2007.

- Lepper, Bradley T. (1999). "Pleistocene Peoples of Midcontinental North America". In Bonnichsen, Robson; Turnmire, Karen (eds.). Ice Age People of North America. Corvallis: Oregon State University Press. pp. 362–394. ISBN 978-0-87071-458-0.

- Kennett, D.J.; Kennett, J.P.; West, A.; et al. (January 2009). "Nanodiamonds in the Younger Dryas boundary sediment layer" (PDF). Science. 323 (5910): 94. Bibcode:2009Sci...323...94K. doi:10.1126/science.1162819. PMID 19119227. S2CID 206514910.

- Hillerman, Tony (June 1980). "The Hunt for the Lost American". The Great Taos Bank Robbery: And Other Indian Country Affairs. University of New Mexico Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-8263-0530-5.

- Dyke, Arthur S.; Prest, Victor K. (1987). "Late Wisconsinan and Holocene History of the Laurentide Ice Sheet" (PDF). Géographie Physique et Quaternaire. 41 (2): 237–263. doi:10.7202/032681ar.

- "Prehistory of Haida Gwaii". Civilization.ca-Haida-The people and the land-Prehistory. Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. June 8, 2001.

- Jameson 1997, p. 159.

- Reynolds, Graham; MacKinnon, Richard; MacDonald, Ken. "Period 1 (10,000–8,000 years ago) Palaeo-Indian culture". Learners Portal. Folkus Atlantic Productions. Archived from the original on July 13, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- Taylor 2002, p. 10.

- Imbrie, J; Imbrie, K.P. (1979). Ice Ages: Solving the Mystery. Short Hills NJ: Enslow Publishers. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-226-66811-6. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- United States. Foreign Agricultural Service (1962). Foreign agriculture. Vol. 24. United States: Bureau of Agricultural Economics. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-16-038463-9.

- Fagan, Brian M. (1992). People of the Earth: An Introduction to World Prehistory. University of California. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-321-01457-3.

- Friesen, John (1997). Rediscovering the First Nations of Canada. Calgary, AB: Detselig Enterprises Ltd. ISBN 978-1-55059-143-9.

- Carlson, Keith Thor, ed. (1997). You Are Asked to Witness: The Stó:lō in Canada's Pacific Coast History. Chilliwack, BC: Stó:lō Heritage Trust. ISBN 978-0-9681577-0-1.

- "American Indian Heritage Month: Commemoration vs. Exploitation". ABC-CLIO. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- Leer, Jeff; Doug Hitch; John Ritter (2001). Interior Tlingit noun dictionary: The dialects spoken by Tlingit elders of Carcross and Teslin, Yukon, and Atlin, British Columbia. Whitehorse, Yukon Territory: Yukon Native Language Centre. ISBN 978-1-55242-227-4.

- Ray 1996.

- "Museum Notes-The Maritime Archaic Tradition". By James A. Tuck-The Rooms Provincial Art Gallery. Archived from the original on May 10, 2006. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- Tuck, J. A. (1976). "Ancient peoples of Port au Choix". The excavation of an Archaic Indian Cemetery in Newfoundland. Newfoundland Social and Economic Studies 17. St. John's: Institute of Social and Economic Research. ISBN 978-0-919666-12-2.

- "The so-called "Red Paint People". Brian Robinson. University of Maine. 1997. Archived from the original on January 14, 2010. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- Fagan, Brian M. (2005). Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent (4 ed.). New York: Thames & Hudson Inc. pp. 390, p396. ISBN 978-0-500-28148-2.

- Winchell 1881, pp. 601–602.

- "C. Prehistoric Periods (Eras of Adaptation)". The University of Calgary (The Applied History Research Group). 2000. Archived from the original on April 12, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2010.

- "A History of the Native People of Canada". Dr. James V. Wright. Canadian Museum of Civilization. 2009. Retrieved October 9, 2009.

- Ohio Historical Society (2009). "Hopewell Culture-Ohio History Central-A product of the Ohio Historical Society". Hopewell-Ohio History Central. Retrieved September 18, 2009.

- Price, Douglas T.; Feinman, Gary M. (2008). Images of the Past, 5th edition. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 274–277. ISBN 978-0-07-340520-9.

- Joe, Rita; Choyce, Lesley (2005). The Native Canadian Anthology. Nimbus Publishing (CN). ISBN 978-1-895900-04-0.

- "civilization – definition of civilization in English from the Oxford dictionary". Oxforddictionaries.com. Archived from the original on July 18, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Prine, Elizabeth (April 17, 2015). "Native American | indigenous peoples of Canada and United States". Britannica.com. Retrieved October 25, 2015.

- Turchin, Peter; Grinin, Leonid; Korotayev, Andrey; de Munck, Victor C. (2006). Moscow: KomKniga/URSS, 2006. (ed.). History and mathematics: Historical Dynamics and Development of complex Societies (URSS.ru-Books on Science-On-line Bookstore.). Editorial URSS. ISBN 978-5-484-01002-8. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- Willey, Gordon R; Phillips, Philip (1957). Method and Theory in American Archaeology. University of Chicago Press. pp. 1(introduction). ISBN 978-0-226-89888-9. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- Woodcock, George (January 25, 1990). "Part 1". A Social History of Canada. Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 978-0-14-010536-0.

- Wolf, Eric (December 3, 1982). "Chapter 6". Europe and the People Without History. University of California Press; 1 edition. ISBN 978-0-520-04898-0. Retrieved October 6, 2009. URL gives introduction online

- Titley, E. Brian (1992). A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada. Vancouver: University Of British Columbia Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-0420-2.

- "Ovide Mercredi installed as chancellor of Manitoba's newest university". CBC News. November 7, 2007. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- "The History of Metropolitan Vancouver's Hall of Fame Joe Capilano". Archived from the original on May 3, 2009. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- Rigby, Bruce. "101. Qaummaarviit Historic Park, Nunavut Handbook" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2006. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- "The Dorsets: Depicting Culture Through Soapstone Carving" (PDF). historysociety.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 30, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- "Inuit Post-Contact History". Memorial University of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Archived from the original on December 18, 2008. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- Gulløv, Hans Christian (2005). Grønlands Forhistorie. Gyldendal A/S. p. 17. ISBN 978-87-02-01724-3.

- Fitzhugh, William W. (2000). Fitzhugh, William W.; Ward, Elisabeth I. (eds.). Vikings: The North Atlantic Saga. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution. pp. 193–205. ISBN 978-1-56098-995-0.

- McGhee, Robert (June–July 1992). "Northern Approaches. Before Columbus: Early European Visitors to the New World". The Beaver. Exploring Canada's History. 3: 194. ISSN 0005-7517.

- Kleivan, H (1966). The Eskimos of Northeast Labrador. Vol. 139. Norsk Polarinstitutt Skrifter. p. 9. OCLC 786916953.

- Minogue, Sarah (September 23, 2005). "When Inuit become zoo curiosities "We sat there like pieces of art in a showcase on display"". Nunatsiaq News. Archived from the original on September 17, 2009. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- "Kiviaq versus Canada film by Zacharias Kunuk Produced by Katarina Soukup" (PDF). Isuma Distribution International Inc. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 14, 2010. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- Hanson, Ann Meekitjuk. "Nunavut 99-What's In A Name? Names, as well as events, mark the road to Nunavut". Nunavut.com. Archived from the original on November 7, 2016. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

- Rinella, Steven (2008). American Buffalo: In Search of A Lost Icon. NY: Spiegel and Grau. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-385-52168-0. Retrieved October 18, 2009.

- Stevenson, Winona (2011). Racism, Colonization and Indigeneity in Canada. Ontario, Canada: Oxford University Press. pp. 44–45.

- Howard, James H (1965). The Plains-Ojibwa or Bungi: hunters and warriors of the Northern Prairies with special reference to the Turtle Mountain band (Museum Anthropology Papers 1 ed.). University of South Dakota. ISBN 978-0-16-050400-6.

- "Singer Tom Jackson pitches housing complex for Winnipeg". Canada: CBC. October 23, 2009. Archived from the original on October 25, 2009. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- Stanley, George F.G. (April 22, 2013). "Louis Riel". The Canadian Encyclopedia. revised by Adam Gaudry. Historica Canada.

- "Louis Riel". A database of materials held by the University of Saskatchewan Libraries and the University Archives. Archived from the original on September 25, 2007. Retrieved September 23, 2007.

- "Backgrounder Biography of Anthony W.J. (Tony) Whitford – NWT Commissioner". 2005 News Releases. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. October 28, 2008. Archived from the original on June 13, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- The Problem of Michif. Peter Bakker-Metis Resource Centre. 1997. ISBN 978-0-19-509711-5. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J.; Dorion, Leah; Hourie, Audreen (2006). Metis legacy Michif culture, heritage, and folkways. Vol. Metis legacy series, v. 2. Saskatoon, SK: Gabriel Dumont Institute. ISBN 978-0-920915-80-6.

- Blain, Eleanor M. (1994). "The Red River dialect". Winnipeg: Wuerz Publishing. Archived from the original on March 15, 2008. Retrieved October 15, 2009.

- Harroun Foster, Martha (January 2006). We know who we are: Métis identity in a Montana community. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8061-3705-6.

- "Her Majesty The Queen vs. Steve Powley and Roddy Charles Powley (R. v. Powley, 2 S.C.R. 207, 2003 SCC 43)" (PDF). Federation of Law Societies of Canada. 2003. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- Houghton Mifflin Company (September 28, 2005). The American Heritage guide to contemporary usage and style. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-618-60499-9.

- Barkwell, Lawrence J.; Dorion, Leah; Prefontaine, Darren (2001). Metis Legacy: A Historiography and Annotated Bibliography. Winnipeg, MB: Pemmican Publications Inc. and Saskatoon: Gabriel Dumont Institute. ISBN 978-1-894717-03-8.

- "Stage Three: Displacement and Assimilation". Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. February 8, 2006. Archived from the original on June 21, 2003. Retrieved October 3, 2009 – via Government of Canada Web Archive.

- Branch, Government of Canada; Indigenous Northern Affairs Canada; Communications (February 8, 2006). "Report-Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples-Indian and Northern Affairs Canada". Volume 1, Part 1, Chapter 6 of the Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. Archived from the original on June 8, 2003. Retrieved October 3, 2009.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Gradual Civilization Act, 1857" (PDF). Government of Canada. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- "Indian Act". Government of Canada. April 8, 2019. Archived from the original on February 16, 2013.

- Armitage, Andrew (1995). Comparing the Policy of Aboriginal Assimilation: Australia, Canada, and New Zealand. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia Press. pp. 77–78.

- Dorsett, Shaunnagh (1995). "Civilisation and Cultivation: Colonial Policy and Indigenous Peoples in Canada and Australia". Griffith Law Review. 4 (2): 219.

- Buckley, Helen (1992). From Wooden Ploughs to Welfare: Why Indian policy failed in the Prairie provinces. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. pp. 52–53. ISBN 0773508937.

- Carter, Sarah (1990). Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian reserve farmers and government policy. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 193. ISBN 0773507558.

- Miller, J. R. (2000). Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Indian-White Relations in Canada. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. p. 140.

- Milloy, John (1999). A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, 1879 to 1986. Winnipeg, Canada: University of Manitoba Press. pp. 21–22.

- Popic, Linda (2008). "Compensating Canada's 'Stolen Generations'". Journal of Aboriginal History (December 2007 – January 2008): 14.

- Charles, Grant; DeGane, Mike (2013). "Student-to-Student Abuse in the Indian Residential Schools in Canada: Setting the Stage for Further Understanding". Child & Youth Services. 34 (4): 343–359. doi:10.1080/0145935X.2013.859903. S2CID 144148882.

- Restoule, Jean-Paul (2002). "Seeing Ourselves. John Macionis and Nijole v. Benokraitis and Bruce Ravelli". Aboriginal Identity: The Need for Historical and Contextual Perspectives. Vol. 24. Toronto, ON: Pearson/Prentice Hall. pp. 102–12. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- Unattributed (February 25, 2012). "Canada commission issues details abuse of native children". BBC. Retrieved February 25, 2012.

- Benjoe, Kerry (June 12, 2008). "Group gathers for Harper's apology". The Leader-Post. Archived from the original on September 15, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- John Borrows (2006). "Indigenous Legal Traditions in Canada" (PDF). Report for the Law Commission of Canada. Law Foundation Chair in Aboriginal Justice and Governance Faculty of Law, University of Victoria.

In Canada, Indigenous legal traditions are separate from but interact with common law and civil law to produce a variety of rights and obligations for Indigenous people....Many Indigenous societies in Canada possess legal traditions. These traditions have indeterminate status in the eyes of many Canadian institutions.

- Kaufman, Amy. "Research Guides: Aboriginal Law & Indigenous Laws: A note on terms". guides.library.queensu.ca.

Indigenous law exists as a source of law apart from the common and civil legal traditions in Canada. Importantly, Indigenous laws also exist apart from Aboriginal law, though these sources of law are interconnected. Aboriginal law is a body of law, made by the courts and legislatures, that largely deals with the unique constitutional rights of Aboriginal peoples and the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Crown. Aboriginal law is largely found in colonial instruments (such as the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the Constitution Acts of 1867 and 1982 and the Indian Act) and court decisions, but also includes sources of Indigenous law. "Indigenous law consists of legal orders which are rooted in Indigenous societies themselves. It arises from communities and First Nation groups across the country, such as Nuu Chah Nulth, Haida, Coast Salish, Tsimshian, Heiltsuk, and may include relationships to the land, the spirit world, creation stories, customs, processes of deliberation and persuasion, codes of conduct, rules, teachings and axioms for living and governing.

- Christian Leuprecht; Peter H. Russell (2011). Essential Readings in Canadian Constitutional Politics. University of Toronto Press. p. 477. ISBN 978-1-4426-0368-4.

- Hall, Anthony J. (June 6, 2011). "Treaties with Indigenous Peoples in Canada | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- Crowe, Keith (March 2, 2015). "Comprehensive Land Claims: Modern Treaties | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- "What is Treaty 8?". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on August 7, 2004. Retrieved October 5, 2009 – via cbc.ca.

- Albers, Gretchen (March 2, 2015). "Indigenous Peoples and Specific Claims | The Canadian Encyclopedia". www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca. Retrieved August 5, 2021.

- "The Indian Act" (PDF). Indian Act. Current to March 16, 2014. Department of Justice Canada. March 16, 2014.

- "First Nations, Bill C-31, Indian Act". Communications Branch. Department of Indian Affairs and Northern Development. Archived from the original on July 30, 2009. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- "Summary of the Final Report of The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples: Implications for Canada's Health Care System" (PDF). The Institute on Governance. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2003. Retrieved October 5, 2009.

- Cairns, Alan (2000). Citizens plus: aboriginal peoples and the Canadian state. UBC Press. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-7748-0767-8.

- McCaslin, Wanda D.; University of Saskatchewan. Native Law Centre (July 2005). Justice as healing: indigenous ways. Living Justice Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-9721886-1-6.

- "Aboriginal Health & Cultural Diversity Glossary". University of Saskatchewan, College of Nursing. 2003. Archived from the original on October 24, 2009. Retrieved October 2, 2009.

- Jacklin, Kristen; Warry, Wayne (2004). "14 Then Indian Health Transfer Policy in Canada: Toward Self-Determination or Cost Containment?". In Castro, Arachu; Singer, Merrill (eds.). Unhealthy health policy: a critical anthropological examination. Oxford United Kingdom: Rowman Altamira. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-7591-0510-2.

- First Nations & Inuit Health Branch (October 25, 2007). "Indian Health Policy 1979". Health Canada. Retrieved October 2, 2009 – via hc-sc.gc.ca.

- Lemchuk-Favel, Laurel (February 22, 1999). "Financing a First Nations and Inuit Integrated Health System A Discussion Document" (PDF). Health Canada. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 11, 2013. Retrieved October 2, 2009 – via hc-sc.gc.ca.

- Waldram, James Burgess; Herring, Ann; Young, T. Kue (July 30, 2006). Aboriginal health in Canada: historical, cultural, and epidemiological perspectives. University of Toronto Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-8020-8579-5.

- Price, Richard (1999). The Spirit of the Alberta Indian Treaties. University of Alberta Press > the University of Michigan. ISBN 978-0-88864-327-8.

- "Post-war Rise of Political Organizations". Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved October 6, 2009.

- "Diverse Peoples – Aboriginal Contributions and Inventions" (PDF). The Government of Manitoba. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- Newhouse, David. "Hidden in Plain Sight Aboriginal Contributions to Canada and Canadian Identity Creating a new Indian Problem" (PDF). Centre of Canadian Studies, University of Edinburgh. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 23, 2011. Retrieved October 17, 2009.

- Trigger, Bruce G.; Pendergast, James F. (1978). Saint-Lawrence Iroquoians. pp. 357–361. ISBN 978-0-16-004575-2.