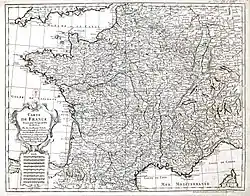

List of heads of state of France

Monarchs ruled the Kingdom of France from the establishment of Francia in 509 to 1870, except for certain periods from 1792 to 1852. Since 1870, the head of state has been the President of France. Below is a list of all French heads of state. It includes the monarchs of the Kingdom of France, emperors of the First and Second Empire and leaders of the five Republics.

|

|---|

Merovingian dynasty (509–751)

The Merovingians were a Salian Frankish dynasty that ruled the Franks for nearly 300 years in a region known as Francia in Latin, beginning in the middle of the 5th century CE. Their territory largely corresponded to ancient Gaul as well as the Roman provinces of Raetia, Germania Superior and the southern part of Germania. The Merovingian dynasty was founded by Childeric I (c. 457 – 481 CE), the son of Merovech, leader of the Salian Franks, but it was his famous son Clovis I (481–511 CE) who united all of Gaul under Merovingian rule.[1][2]

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Death | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Clovis I (Clovis Ier) |

509 | 511 | Likely died of natural causes aged 46. Buried at Abbey of St Genevieve until 18th century. Remains relocated to Basilica of St Denis. | • Son of Childeric I | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Childebert I (Childebert Ier) |

511 | 13 December 558 | Died aged 64. Buried at Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. | • Son of Clovis I | King of Paris (Roi de Paris) |

|

Chlothar I the Old (Clotaire Ier le Vieux) |

13 December 558 | 29 November 561 | Died aged 64. Buried at Abbey of St. Medard, Soissons. | • Son of Clovis I • Younger brother of Childebert I |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

_-_Caribert%252C_roi_franc_de_Paris_et_de_l'ouest_de_Gaule_(mort_en_567).jpg.webp) |

Charibert I (Caribert Ier) |

29 November 561 | 567 | Died aged 50. Buried at Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. | • Son of Chlothar I | King of Paris (Roi de Paris) |

|

Chilperic I (Chilpéric Ier) |

567 | 584 | Died aged 45. Buried at Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. | • Son of Chlothar I • Younger brother of Charibert I |

King of Paris (Roi de Paris) King of Neustria (Roi de Neustrie) |

|

Chlothar II the Great, the Young (Clotaire II le Grand, le Jeune) |

584 | 18 October 629 | Died aged 45. Buried at Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. | • Son of Chilperic I | King of Neustria (Roi de Neustrie) King of Paris (Roi de Paris) (595–629) King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) (613–629) |

|

Dagobert I (Dagobert Ier) |

18 October 629 | 19 January 639 | Died aged 36. Buried at Basilica of St Denis. | • Son of Chlothar II | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Clovis II the Lazy (Clovis II le Fainéant) |

19 January 639 | 31 October 657 | Died aged 20. Buried at Basilica of St Denis. | • Son of Dagobert I | King of Neustria and Burgundy (Roi de Neustrie et de Bourgogne) |

|

Chlothar III (Clotaire III) |

31 October 657 | 673 | Died aged 21. Buried at Basilica of St Denis. | • Son of Clovis II | King of Neustria and Burgundy (Roi de Neustrie et de Bourgogne) King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) (657–663) |

|

Childeric II (Childéric II) |

673 | 675 | Died aged 22. Buried at Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. | • Son of Clovis II • Younger brother of Chlothar III |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Theuderic III (Thierry III) |

675 | 691 | Died aged 37. | • Son of Clovis II • Younger brother of Childeric II |

King of Neustria (Roi de Neustrie) King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) (687–691) |

_-_Clovis_III_roi_d'Austrasie_en_691_(682-695).jpg.webp) |

Clovis IV (Clovis IV) |

691 | 695 | Died aged 13. | • Son of Theuderic III | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Childebert III the Just (Childebert III le Juste) |

695 | 23 April 711 | Died aged 41. Buried at Church of St Stephen at Choisy-au-Bac, near Compiègne. | • Son of Theuderic III • Younger brother of Clovis IV |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

.jpg.webp) |

Dagobert III | 23 April 711 | 715 | Died aged 14. | • Son of Childebert III | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Chilperic II (Chilpéric II) |

715 | 13 February 721 | Died aged 49. Buried at Noyon. | • Probably son of Childeric II | King of Neustria and Burgundy (Roi de Neustrie et de Bourgogne) King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) (719–721) |

|

Theuderic IV | 721 | 737 | Died aged 25. | • Son of Dagobert III | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

The last Merovingian kings, known as the "lazy kings" (rois fainéants), did not hold any real political power, while the Mayor of the Palace governed instead. When Theuderic IV died in 737, Mayor of the Palace Charles Martel left the throne vacant and continued to rule until his own death in 741. His sons Pepin and Carloman briefly restored the Merovingian dynasty by raising Childeric III to the throne in 743. In 751, Pepin deposed Childerich and acceded to the throne.

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Death | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_-_Child%C3%A9ric_III_roy_de_France_(754).jpg.webp) |

Childeric III (Childéric III) |

743 | November 751 | Died aged 37. | • Son of Chilperic II or of Theuderic IV | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

Carolingian dynasty (751–888)

The Carolingian dynasty was a Frankish noble family with origins in the Arnulfing and Pippinid clans of the 7th century AD. The family consolidated its power in the late 8th century, eventually making the offices of Mayor of the Palace and dux et princeps Francorum hereditary and becoming the de facto rulers of the Franks as the real powers behind the throne. By 751, the Merovingian dynasty, which until then had ruled the Germanic Franks by right, was deprived of this right with the consent of the Papacy and the aristocracy, and a Carolingian, Pepin the Short, was crowned King of the Franks.[3][2]

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pepin the Younger, the Short (Pépin le Bref) |

751 | 24 September 768 | • Son of Charles Martel | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Carloman I | 24 September 768 | 4 December 771 | • Son of Pepin the Short | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Charlemagne (Charles I, the Great) | 24 September 768 | 28 January 814 | • Son of Pepin the Short | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) Emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) (800–814) |

|

Louis I the Pious, the Debonaire (Louis Ier le Pieux, le Débonnaire) |

28 January 814 | 20 June 840 | • Son of Charlemagne | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) Emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) |

|

Charles II the Bald (Charles II le Chauve) |

20 June 840 | 6 October 877 | • Son of Louis I | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) Emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) (875–877) |

|

Louis II the Stammerer (Louis II le Bègue) |

6 October 877 | 10 April 879 | • Son of Charles II | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Louis III | 10 April 879 | 5 August 882 | • Son of Louis II | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Carloman II | 5 August 882 | 6 December 884 | • Son of Louis II | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Charles III the Fat (Charles le Gros) |

20 May 885 | 13 January 888 | • Son of Louis the German • Cousin of Louis II and Carloman II • Grandson of Louis I the Pious |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) Emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) (881–887) |

Robertian dynasty (888–898)

The Robertians were Frankish noblemen owing fealty to the Carolingians, and ancestors of the subsequent Capetian dynasty. Odo, Count of Paris was chosen by the western Franks to be their king following the removal of emperor Charles the Fat. He was crowned at Compiègne in February 888 by Walter, Archbishop of Sens.[4][2]

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Odo of Paris (Eudes de Paris) |

29 February 888 | 1 January 898 | • Son of Robert the Strong (Robertians) • Elected king against young Charles III. |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

Carolingian dynasty (893–922)

Charles, the posthumous son of Louis II, was crowned by a faction opposed to the Robertian Odo at Reims Cathedral, though he only became the effectual monarch with the death of Odo in 898.[5][2]

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_-_Charles_III%252C_dit_le_simple%252C_roi_de_France_en_896_(879-929).jpg.webp) |

Charles III the Simple (Charles III le Simple) |

28 January 898 | 30 June 922 | • Posthumous son of Louis II • Younger half-brother of Louis III and Carloman II |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

Robertian dynasty (922–923)

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Robert I (Robert Ier) |

30 June 922 | 15 June 923 | • Son of Robert the Strong (Robertians)[2] • Younger brother of Odo |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

Bosonid dynasty (923–936)

The Bosonids were a noble family descended from Boso the Elder, their member, Rudolph (Raoul), was elected "King of the Franks" in 923.

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Rudolph (Raoul de France) |

13 July 923 | 14 January 936 | • Son of Richard, Duke of Burgundy (Bosonids) • Son-in-law of Robert I |

King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

Carolingian dynasty (936–987)

| Portrait | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Louis IV of Outremer (Louis IV d'Outremer) |

19 June 936 | 10 September 954 | • Son of Charles III[2] | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Lothair (Lothaire de France) |

12 November 954 | 2 March 986 | • Son of Louis IV | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

|

Louis V the Lazy (Louis V le Fainéant) |

8 June 986 | 22 May 987 | • Son of Lothair | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

Capetian dynasty (987–1792)

After the death of Louis V, the son of Hugh the Great and grandson of Robert I, Hugh Capet, was elected by the nobility as king of France. The Capetian Dynasty, the male-line descendants of Hugh Capet, ruled France continuously from 987 to 1792 and again from 1814 to 1848. They were direct descendants of the Robertian kings. The cadet branches of the dynasty which ruled after 1328, however, are generally given the specific branch names of Valois and Bourbon.

Not listed below are Hugh Magnus, eldest son of Robert II, and Philip of France, eldest son of Louis VI; both were co-Kings with their fathers (in accordance with the early Capetian practice whereby kings would crown their heirs in their own lifetimes and share power with the co-king), but predeceased them. Because neither Hugh nor Philip were sole or senior king in their own lifetimes, they are not traditionally listed as Kings of France, and are not given ordinals.

Henry VI of England, son of Catherine of Valois, became titular King of France upon his grandfather Charles VI's death in accordance with the Treaty of Troyes of 1420 however this was disputed and he is not always regarded as a legitimate king of France.

From 21 January 1793 to 8 June 1795, Louis XVI's son Louis-Charles was the titular King of France as Louis XVII; in reality, however, he was imprisoned in the Temple throughout this duration, and power was held by the leaders of the Republic. Upon Louis XVII's death, his uncle (Louis XVI's brother) Louis-Stanislas claimed the throne, as Louis XVIII, but only became de facto King of France in 1814.

House of Capet (987–1328)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hugh Capet (Hugues Capet) | 3 July 987 | 24 October 996 | • Grandson of Robert I[2] | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) | |

| Robert II the Pious, the Wise (Robert II le Pieux, le Sage) | 24 October 996 | 20 July 1031 | • Son of Hugh Capet | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) | |

| Henry I (Henri Ier) | 20 July 1031 | 4 August 1060 | • Son of Robert II | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) | |

| Philip I the Amorous (Philippe Ier l' Amoureux) | 4 August 1060 | 29 July 1108 | • Son of Henry I | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) | |

| Louis VI the Fat (Louis VI le Gros) | 29 July 1108 | 1 August 1137 | • Son of Philip I | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) | |

| .svg.png.webp) | Louis VII the Young (Louis VII le Jeune) | 1 August 1137 | 18 September 1180 | • Son of Louis VI | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) |

.jpg.webp) | .svg.png.webp) | Philip II Augustus (Philippe II Auguste) | 18 September 1180 | 14 July 1223 | • Son of Louis VII | King of the Franks (Roi des Francs) first monarch to use the title of King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Louis VIII the Lion (Louis VIII le Lion) | 14 July 1223 | 8 November 1226 | • Son of Philip II Augustus | King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Louis IX the Saint (Saint Louis) | 8 November 1226 | 25 August 1270 | • Son of Louis VIII | King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Philip III the Bold (Philippe III le Hardi) | 25 August 1270 | 5 October 1285 | • Son of Louis IX | King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Philip IV the Fair, the Iron King (Philippe IV le Bel) | 5 October 1285 | 29 November 1314 | • Son of Philip III | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Louis X the Quarreller (Louis X le Hutin) | 29 November 1314 | 5 June 1316 | • Son of Philip IV | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

| .svg.png.webp) | John I the Posthumous (Jean Ier le Posthume) | 15 November 1316 | 20 November 1316 | • Son of Louis X | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Philip V the Tall (Philippe V le Long) | 20 November 1316 | 3 January 1322 | • Son of Philip IV • Younger brother of Louis X |

King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Charles IV the Fair (Charles IV le Bel) | 3 January 1322 | 1 February 1328 | • Son of Philip IV • Younger brother of Louis X and Philip V |

King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

House of Valois (1328–1589)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .svg.png.webp) | Philip VI of Valois, the Fortunate (Philippe VI de Valois, le Fortuné) | 1 April 1328 | 22 August 1350 | • Grandson of Philip III of France[6] | King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) | John II the Good (Jean II le Bon) | 22 August 1350 | 8 April 1364 | • Son of Philip VI | King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) .svg.png.webp) | Charles V the Wise (Charles V le Sage) | 8 April 1364 | 16 September 1380 | • Son of John II | King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Charles VI the Beloved, the Mad (Charles VI le Bienaimé, le Fol) | 16 September 1380 | 21 October 1422 | • Son of Charles V | King of France (Roi de France) |

House of Lancaster (1422–1453), disputed

From 1340 to 1801 (but not from 1360 to 1369), the Kings of England and Great Britain claimed the title of King of France. Under the terms of the 1420 Treaty of Troyes, Charles VI had recognized his son-in-law Henry V of England as regent and heir. Henry V predeceased Charles VI and so Henry V's son, Henry VI, succeeded his grandfather Charles VI as King of France. Most of Northern France was under English control until 1435, but by 1453, the English had been expelled from all of France save Calais (and the Channel Islands), and Calais itself fell in 1558. Nevertheless, English and then British monarchs continued to claim the title for themselves until the creation of the United Kingdom in 1801.

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Claim | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | .svg.png.webp) | Henry VI of England (Henri VI d'Angleterre) | 21 October 1422 | 19 October 1453 | • By right of his father Henry V of England by the Treaty of Troyes become heir and regent to the French throne | King of France (Roi de France) |

House of Valois (1328–1589)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .svg.png.webp) | Charles VII the Victorious, the Well-Served (Charles VII le Victorieux, le Bien-Servi) | 21 October 1422 | 22 July 1461 | • Son of Charles VI[6] | King of France (Roi de France) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Louis XI the Prudent, the Cunning, the Universal Spider (Louis XI le Prudent, le Rusé, l'Universelle Aragne) | 22 July 1461 | 30 August 1483 | • Son of Charles VII | King of France (Roi de France) |

|  | Charles VIII the Affable (Charles VIII l'Affable) | 30 August 1483 | 7 April 1498 | • Son of Louis XI | King of France (Roi de France) |

Orléans branch (1498–1515)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

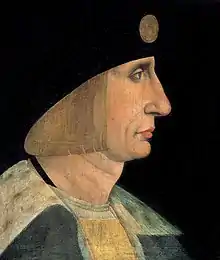

| .svg.png.webp) | Louis XII Father of the People (Louis XII le Père du Peuple) | 7 April 1498 | 1 January 1515[2] | • Great-grandson of Charles V • Second cousin, and by first marriage son-in-law of Louis XI • By second marriage husband of Anne of Brittany, widow of Charles VIII |

King of France (Roi de France) |

Orléans–Angoulême Branch (1515–1589)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  | Francis I the Father and Restorer of Letters (François Ier le Père et Restaurateur des Lettres) | 1 January 1515 | 31 March 1547[2] | • Great-great-grandson of Charles V • First cousin once removed, and by first marriage son-in-law of Louis XII |

King of France (Roi de France) |

|  | Henry II (Henri II) | 31 March 1547 | 10 July 1559 | • Son of Francis I/Maternal grandson of Louis XII | King of France (Roi de France) |

|  | Francis II (François II) | 10 July 1559 | 5 December 1560 | • Son of Henry II | King of France (Roi de France) King of Scots (1558–1560) |

|  | Charles IX | 5 December 1560 | 30 May 1574 | • Son of Henry II | King of France (Roi de France) |

|  | Henry III (Henri III) | 30 May 1574 | 2 August 1589 | • Son of Henry II | King of France (Roi de France) King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania (1573–1575) |

House of Bourbon (1589–1792)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  | Henry IV, Good King Henry, the Green Gallant (Henri IV, le Bon Roi Henri, le Vert-Galant) | 2 August 1589 | 14 May 1610 | • Tenth generation descendant of Louis IX in the male line • By first marriage son in law of Henry II, Brother in law of Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III |

King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

|  | Louis XIII the Just (Louis XIII le Juste) | 14 May 1610 | 14 May 1643 | • Son of Henry IV | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) |  | Louis XIV the Great, the Sun King (Louis XIV le Grand, le Roi Soleil) | 14 May 1643 | 1 September 1715 | • Son of Louis XIII | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

|  | Louis XV the Beloved (Louis XV le Bien-Aimé) | 1 September 1715 | 10 May 1774 | • Great-grandson of Louis XIV | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

%252C_rev%C3%AAtu_du_grand_costume_royal_en_1779_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) |  | Louis XVI the Restorer of French Liberty (Louis XVI le Restaurateur de la Liberté Française) | 10 May 1774 | 21 September 1792 | • Grandson of Louis XV | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) (1774–1791) King of the French (Roi des Français) (1791–1792) |

|  | Louis XVII (Claimant) | 21 January 1793 | 8 June 1795 | • Son of Louis XVI | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

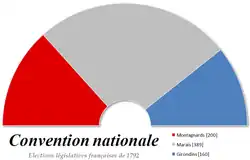

French First Republic (1792–1804)

National Convention Convention nationale | |

|---|---|

| French First Republic | |

Autel de la Convention nationale or Autel républicain François-Léon Sicard Panthéon de Paris, France, 1913 | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Established | 20 September 1792 |

| Disbanded | 2 November 1795 |

| Preceded by | Legislative Assembly |

| Succeeded by | Directory Executive branch Council of Ancients (upper house) Council of Five Hundred (lower house) |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 749 |

| |

Political groups |

|

| Meeting place | |

| Tuileries Palace, Paris | |

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

Presidents of the National Convention

The first President of France is considered to be Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (later Napoleon III), who was elected in the 1848 election, under the French Second Republic.

From 22 September 1792 to 2 November 1795, the French Republic was governed by the National Convention, whose president (elected from within for a 14-day term) may be considered as France's legitimate Head of State during this period. Historians generally divide the Convention's activities into three periods, moderate, radical, and reaction, and the policies of presidents of the Convention reflect these distinctions. During the radical and reaction phases, some of the presidents were executed, most by guillotine, committed suicide, or were deported. In addition, some of the presidents were later deported during the Bourbon Restoration in 1815.

Establishment of the Convention

The National Convention governed France from 20 September 1792 until 26 October 1795 during the most critical period of the French Revolution. The election of the National Convention took place in September 1792 after the election of the electoral colleges by primary regional assemblies on 26 August. Owing to the abstention of aristocrats and the anti-republicans, and the general fear of victimization, the voter turnout in the departments was low – as little as 7.5 percent or as much as 11.9% of the electorate, compared to 10.2% in the 1791 elections, despite the doubling of the number of eligible voters.[7]

Initially elected to provide a new constitution after the overthrow of the monarchy on 10 August 1792, the Convention included 749 deputies drawn from businesses and trades, and from such professions as law, journalism, medicine, and the clergy. Among its earliest acts was the formal abolition of the monarchy, through Proclamation, on 21 September, and the subsequent establishment of the Republic on 22 September. The French Republican Calendar discarded all Christian reference points and calculated time from the Republic's first full day after the monarchy – 22 September 1792, the first day of Year One.[8][9]

According to its own rules, the Convention elected its President every fortnight (two weeks). He was eligible for re-election after the lapse of a fortnight. Ordinarily the sessions were held in the morning, but evening sessions also occurred frequently, often extending late into the night. In exceptional circumstances, the Convention declared itself in permanent session and sat for several days without interruption. For both legislative and administrative deliberations, the Convention used committees, with powers more or less widely extended and regulated by successive laws.[10] The most famous of these committees included the Committee of Public Safety and the Committee of General Security.[9]

The Convention held both legislative and executive powers during the first years of the French First Republic and had three distinct periods: Girondins (moderate), Montagnard (radical) and Thermidorian (reaction). The Montagnards favored granting the poorer classes more political power; the Girondins favored a bourgeois republic and wanted to reduce the power and influence of Paris over the course of the revolution. A popular uprising in Paris helped to purge the Convention of the Girondins between 31 May and 2 June 1793;[9] the last of the Girondins served as presidents in late July.[11]

In its second phase, the Montagnards controlled the convention (June 1793 to July 1794). War and an internal rebellion convinced the revolutionary government to establish a Committee of Public Safety which exercised near dictatorial power. Consequently, the democratic constitution, approved by the convention on 24 June 1793, did not go into effect and the Convention lost its legislative initiative.[9] The rise of Mountaineers (Montagnards) corresponded with the decline of the Girondins. The Girondin party had hesitated on the correct course of action to take with Louis XVI after his attempt to flee France on 20 June 1791. Some elements of the Girondin party believed they could use the king as figurehead. While the Girondins hesitated, the Montagnards took a united stand during the trial in December 1792 – January 1793 and favored the king's execution.[12] Riding on this victory, the Montagnards then sought to discredit the Girondins using tactics previously used against themselves, denouncing the Girondins as liars and enemies of the Revolution.[13] The last quarter of the year was marked by the Reign of Terror (5 September 1793 – 28 July 1794),[14] also known as The Terror (French: la Terreur), a period of violence incited by conflict between these rival political factions, the Girondins and the Jacobins, and marked by mass executions of "enemies of the revolution". The death toll ranged in the tens of thousands, with 16,594 executed by guillotine (2,639 in Paris),[13] and another 25,000 in summary executions across France.[15] Most of the Parisian victims of the guillotine filled the Madeleine, Mosseaux (also called Errancis), and Picpus cemeteries.[16]

In the third phase, called Thermidor after the month in which it began, many of the members of the Convention overthrew the most prominent member of the committee, Maximilien Robespierre. This reaction to the radical influence of the Committee of Public Safety reestablished the balance of power in the hands of the moderate deputies. The Girondins who had survived the 1793 purge were recalled and the leading Montagnards were themselves purged, and many executed. In August 1795, the Convention approved the Constitution for the regime that replaced it, the bourgeois-dominated Directory, which exercised power from 1795 to 1799, when a coup d'etat by Napoleon Bonaparte overthrew it.[9]

Moderate Phase: September 1792 – June 1793

Initially, La Marais, or The Plain, a moderate, amorphous group, controlled the Convention. At the first session, held on 20 September 1792, the elder statesman Philippe Rühl presided over the session. The following day, amidst profound silence, the proposition was put to the assembly, "That royalty be abolished in France"; it carried, with cheers. On the 22nd came the news of the Republic's victory at the Battle of Valmy. On the same day, the Convention decreed that "in future, the acts of the assembly shall be dated First Year of the French Republic". Three days later, the Convention added the corollary of "the French republic is one and indivisible", to guard against federalism.[17]

The following men were elected for two-week terms as Presidents, or executives, of the Convention.[18]

| Image | Dates | Name | Fate |

|---|---|---|---|

.JPG.webp) |

20 September 1792 | Philippe Rühl | Suicide, 29/30 May 1795 |

|

20 September 1792 – 4 October 1792 | Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve | Botched suicide, guillotined 18 June 1794 |

.JPG.webp) |

4 October 1792 – 18 October 1792 | Jean-François Delacroix | Guillotined with Georges Danton, 5 April 1794 |

|

18 October 1792 – 1 November 1792 | Marguerite-Élie Guadet | Guillotined 17 June 1794 |

_-_P2539_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet.jpg.webp) |

1 November 1792 – 15 November 1792 | Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles | Guillotined with Georges Danton, 5 April 1794 |

|

15 November 1792 – 29 November 1792 | Henri Grégoire | Died 28 May 1831 |

|

29 November 1792 – 13 December 1792 | Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac | Died 13 January 1841 |

|

13 December 1792 – 27 December 1792 | Jacques Defermon des Chapelieres | 20 June 1831 |

|

27 December 1792 – 10 January 1793 | Jean-Baptiste Treilhard | Died 1 December 1810 |

|

10 January 1793 – 24 January 1793 | Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud | 31 October 1793, guillotined. |

|

24 January 1793 – 7 February 1793 | Jean-Paul Rabaut Saint-Étienne | 5 December 1793, guillotined |

|

7 February 1793 – 21 February 1793 | Jean-Jacques Bréard, dit Bréard-Duplessis | 2 January 1840 |

|

21 February 1793 – 7 March 1793 | Edmond Louis Alexis Dubois-Crancé | 29 June 1814 |

|

7 March 1793 – 21 March 1793 | Armand Gensonné | 31 October 1793, guillotined |

.JPG.webp) |

21 March 1793 – 4 April 1793 | Jean Antoine Joseph Debry | 6 January 1834, Paris |

| 4 April 1793 – 18 April 1793 | Jean-François-Bertrand Delmas | Disappeared 19 August 1798[Notes 1] | |

| 18 April 1793 – 2 May 1793 | Marc David Alba Lasource | 31 October 1793, guillotined with the Girondists | |

|

2 May 1793 – 16 May 1793 | Jean-Baptiste Boyer-Fonfrède | 31 October 1793, guillotined |

|

16 May 1793 – 30 May 1793 | Maximin Isnard | 12 March 1825 |

| 30 May 1793 – 13 June 1793 | François-René-Auguste Mallarmé | 25 July 1835 | |

At the end of May 1793, an uprising of the Parisian sans culottes, the day-laborers and working class, undermined much of the authority of the moderate Girondins.[19] At this point, although Danton and Hérault de Séchelles both served one more term each as Presidents of the Convention, the Girondins had lost control of the Convention: in June and July compromise after compromise changed the course of the revolution from a bourgeois event to a radical, working class event. Price controls were introduced and a minimum wage guaranteed to workers and soldiers. Over the course of the summer, the government became truly revolutionary.[20]

Radical phase: June 1793 – July 1794

After the insurrection, any attempted resistance to revolutionary ideals was crushed. The insurrection of 31 May – 2 June 1793 marked a significant milestone in the history of the French Revolution. The days of 31 May – 2 June (French: journées) resulted in the fall of the Girondin party under pressure of the Parisian sans-culottes, Jacobins of the clubs, and Montagnards in the National Convention. The following men were elected as presidents of the Convention during its transition from its moderate to radical phase.[11]

| Portrait | Dates | Name | Death |

|---|---|---|---|

|

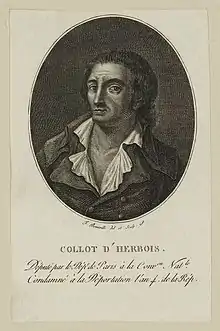

13 June 1793 – 27 June 1793 | Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois | 8 June 1796, deported to French Guiana, died of yellow fever |

| 27 June 1793 – 11 July 1793 | Jacques Alexis Thuriot de la Rosière | 20 June 1829, died in exile | |

|

11 July 1793 – 25 July 1793 | Andre Jeanbon Saint Andre | 10 December 1813 |

%252C_orateur_et_homme_politique_-_P712_-_mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet.jpg.webp) |

25 July 1793 – 8 August 1793 | Georges Jacques Danton | A moderate guillotined by the radicals, 5 April 1794 |

|

8 August 1793 – 22 August 1793 | Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles | Guillotined with Georges Danton, 5 April 1794 |

After 1793, President of the National Convention became a puppet office under the Committee of Public Safety The following men were elected as presidents of the Convention during its radical phase.[11]

| Portrait | Dates | Name | Death |

|---|---|---|---|

|

22 August 1793 – 5 September 1793 | Maximilien Robespierre | 28 July 1794, guillotined during the Reaction |

|

5 September 1793 – 19 September 1793 | Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varenne | 3 June 1819 |

|

19 September 1793 – 3 October 1793 | Pierre Joseph Cambon | 15 February 1820 |

| 3 October 1793 – 22 October 1793 | Louis-Joseph Charlier | 23 February 1797 | |

| 22 October 1793 – 6 November 1793 | Moïse Antoine Pierre Jean Bayle | 1812 or 1815 | |

| 6 November 1793 – 21 November 1793 | Pierre-Antoine Lalloy | 16 March 1846 | |

|

21 November 1793 – 6 December 1793 | Charles-Gilbert Romme | 17 June 1795, suicide prior to guillotine |

| 6 December 1793 – 21 December 1793 | Jean-Henri Voulland | 23 February 1801 | |

%252C_conventionnel_-_P16_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet.jpg.webp) |

21 December 1793 – 5 January 1794 | Georges Auguste Couthon | 28 July 1794, guillotined during the Reaction One of the few members of La Marais to be elected President |

|

5 January 1794 – 20 January 1794 | Jacques-Louis David | 29 December 1825 |

%252C_French_revolutionary_(small).jpg.webp) |

20 January 1794 – 4 February 1794 | Marc Guillaume Alexis Vadier | 14 December 1828 |

| 4 February 1794 – 19 February 1794 | Joseph-Nicolas Barbeau du Barran | 16 May 1816, exiled in Switzerland during Bourbon Restoration | |

|

19 February 1794 – 6 March 1794 | Louis Antoine de Saint-Just | 28 July 1794, guillotine during Reaction |

| 7 March 1794 – 21 March 1794 | Philippe Rühl | 29/30 May 1795, suicide | |

|

21 March 1794 – 5 April 1794 | Jean-Lambert Tallien | 16 November 1820 |

| 5 April 1794 – 20 April 1794 | Jean-Baptiste-André Amar | 21 December 1816 | |

|

20 April 1794 – 5 May 1794 | Robert Lindet | 17 February 1825 |

|

5 May 1794 – 20 May 1794 | Lazare Carnot | 2 August 1823 |

|

20 May 1794 – 4 June 1794 | Claude-Antoine Prieur-Duvernois | 11 August 1832 |

|

4 June 1794 – 19 June 1794 | Maximilien Robespierre | 28 July 1794, guillotined during the Reaction |

| 19 June 1794 – 5 July 1794 | Élie Lacoste | 26 November 1806 | |

| 5 July 1794 – 19 July 1794 | Jean-Antoine Louis, also called Louis du Bas-Rhin | ||

Reaction: July 1794–1795

In 1794, Maximilien Robespierre continued to consolidate his power over the Montagnards with the use of the Committee of Public Safety.[21] By late spring, the moderate members of the Convention had had enough. They began to conspire secretly against Robespierre and his allies. The Thermidorian Reaction was a revolt within the Convention against the leadership of the Jacobin Club over the Committee of Public Safety. The National Convention voted to remove Maximilien Robespierre, Louis Antoine de Saint-Just, and several other leading members of the revolutionary government, and they were executed the following day. This ended the most radical phase of the French Revolution.[22][Notes 2]

The following men were Presidents of the Convention until its end.[11]

| Portrait | Dates | Name | Death |

|---|---|---|---|

|

19 July 1794 – 3 August 1794 | Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois | 8 June 1796 |

|

3 August 1794 – 18 August 1794 | Philippe Antoine Merlin, dit Merlin de Douai | 26 December 1838 |

| 18 August 1794 – 2 September 1794 | Antoine Merlin de Thionville | 14 September 1833 | |

|

2 September 1794 – 22 September 1794 | André Antoine Bernard, dit Bernard de Saintes | 19 October 1818 |

| 22 September 1794 – 7 October 1794 | André Dumont | 19 October 1838 | |

|

7 October 1794 – 22 October 1794 | Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès | 8 March 1824 One of the few members of La Marais to be elected President Authored Napoleon's Civil Code |

|

22 October 1794 – 6 November 1794 | Pierre-Louis Prieur, dit Prieur de la Marne | 31 May 1827 |

|

6 November 1794 – 24 November 1794 | Louis Legendre | 13 December 1797, died of natural causes (dementia) |

| 24 November 1794 – 6 December 1794 | Jean-Baptiste Clauzel | 2 July 1803 | |

|

6 December 1794 – 21 December 1794 | Jean-François Reubell | 23 November 1807 |

| 21 December 1794 – 6 January 1795 | Pierre-Louis Bentabole | 1797 | |

|

6 January 1795 – 20 January 1795 | Étienne-François Le Tourneur | 4 October 1817 |

.JPG.webp) |

20 January 1795 – 4 February 1795 | Stanislas Joseph François Xavier Rovère | died in 1798 in French Guiana |

|

4 February 1795 – 19 February 1795 | Paul Barras | 29 January 1829 |

.JPG.webp) |

19 February 1795 – 6 March 1795 | François Louis Bourdon | 22 June 1798, after being deported to French Guiana |

.JPG.webp) |

6 March 1795 – 24 March 1795 | Antoine Claire Thibaudeau | 8 March 1854 |

.jpg.webp) |

24 March 1795 – 5 April 1795 | Jean Pelet, also Pelet de la Lozère | 26 January 1842 |

|

5 April 1795 – 20 April 1795 | François-Antoine de Boissy d'Anglas | 1828 One of the few members of La Marais to be elected President |

|

20 April 1795 – 5 May 1795 | Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès | 20 June 1836 One of the few members of La Marais to be elected President |

|

5 May 1795 – 26 May 1795 | Théodore Vernier | |

| 26 May 1795 – 4 June 1795 | Jean-Baptiste Charles Matthieu | ||

|

4 June 1795 – 19 June 1795 | Jean Denis, comte Lanjuinais | died in 1828 in Paris |

|

19 June 1795 – 4 July 1795 | Jean-Baptiste Louvet de Couvray | 25 August 1797 |

|

4 July 1795 – 19 July 1795 | Louis-Gustave Doulcet de Pontécoulant | 17 November 1764 – 3 April 1853 |

.JPG.webp) |

19 July 1795 – 3 August 1795 | Louis-Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux | 24 March 1824 |

.JPG.webp) |

3 August 1795 – 19 August 1795 | Pierre Claude François Daunou | 20 June 1840 |

|

19 August 1795 – 2 September 1795 | Marie-Joseph Chénier | 10 January 1811 |

| 2 September 1795 – 23 September 1795 | Théophile Berlier | 12 September 1844 | |

| 23 September 1795 – 8 October 1795 | Pierre-Charles-Louis Baudin | 1799 | |

| 8 October 1795 – 26 October 1795 | Jean Joseph Victor Génissieu | 27 October 1804 |

Presidents of the Committee of Public Safety

- Political parties

Montagnard

Thermidorian

Marais

| No. | Portrait | Name (birth and death) |

Term of office | Political party | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | %252C_orateur_et_homme_politique_-_P712_-_mus%C3%A9e_Carnavalet.jpg.webp) |

Georges Danton (1759–1794) |

6 April 1793 | 27 July 1793 | Montagnard | [23] |

| When all executive power was conferred upon a Committee of Public Safety, Danton had been one of the nine original members of that body. He was dispatched on frequent missions from the Convention to the republican armies in Belgium, and wherever he went he infused new energy into the army. He pressed forward the new national system of education, and he was one of the legislative committee charged with the construction of a new system of government. | ||||||

| 2 |  |

Maximilien Robespierre (1758–1794) |

27 July 1793 | 27 July 1794 | Montagnard | [24] |

| When Robespierre took the power, the "Reign of Terror" was established. Monarchists, Girondists, Modérés but also commonly citizens were guillotined. The Roman Catholicism was replaced by the Cult of the Supreme Being. After one year of absolute power, Robespierre was deposed by the Thermidorian Reaction and executed. | ||||||

| 3 |  |

Jacques Nicolas Billaud-Varenne (1756–1819) |

31 July 1794 | 1 September 1794 | Montagnard | [25] |

| After the Robespierre's execution, Billaud-Varenne, that was one of traitors, became the acting chief of the Committee of Public Safety. He was then attacked himself in the Convention for his ruthlessness, and a commission was appointed to examine his conduct and that of some other members of the former Committee of Public Safety and decreed his immediate deportation to French Guiana. | ||||||

| 4 |  |

Philippe-Antoine Merlin de Douai (1754–1838) |

5 March 1795 | 5 April 1795 | Thermidorian | |

| After the Thermidorian Reaction, he became president of the Convention and a member of the Committee of Public Safety. Merlin de Douai convinced the Committee of Public Safety to agree with the closing of the Jacobin Club, on the ground that it was an administrative rather than a legislative measure. Merlin de Douai recommended the readmission of the survivors of the Girondists to the Convention, and drew up a law limiting the right of insurrection. | ||||||

| 5 |  |

Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès (1753–1824) |

5 April 1795 | 2 August 1795 | Marais | |

| Cambacérès was considered too conservative to be one of the five Directors who took power in the coup of 1795, and finding himself in opposition to the nascent Executive Directory he retired from politics. | ||||||

| 6 |  |

Philippe-Antoine Merlin de Douai (1754–1838) |

2 August 1795 | 1 September 1795 | Thermidorian | |

| - | ||||||

| 7 |  |

Jean Jacques Régis de Cambacérès (1753–1824) |

1 September 1795 | 27 October 1795 | Marais | |

The Directory

The Directory (French: Directoire) was the government of France following the collapse of the National Convention in late 1795. Administered by a collective leadership of five directors, it preceded the Consulate established in a coup d'etat by Napoleon. It lasted from 2 November 1795 until 10 November 1799, a period commonly known as the "Directory era". The directory operated with a bicameral structure. A Council of the Ancients, selected by lot, named the directors. For its own security, the Left (whose members dominated the Council) resolved that all five must be old members of the Convention and regicides who had voted to execute King Louis XVI. The Ancients chose Jean-François Rewbell; Paul François Jean Nicolas, vicomte de Barras; Louis Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux; Lazare Nicolas Marguerite Carnot; and Étienne-François Le Tourneur.[11]

The Directory was officially led by a president, as stipulated by Article 141 of the Constitution of the Year III. An entirely ceremonial post, the first president was Rewbell who was chosen by lot on 2 November 1795. The directors conducted their elections privately, with the presidency rotating every three months.[26] The last president was Gohier.[27]

The key figure of the Directory was Paul Barras, the only Director to serve throughout the Directory.

| Directors of the Directory (1 November 1795 – 10 November 1799) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Paul Barras |

.JPG.webp) Louis-Marie de La Révellière-Lépeaux |

Jean-François Rewbell |

.JPG.webp) Lazare Carnot |

.JPG.webp) Étienne-François Letourneur |

| Letourneur drawn by lot to be replaced 1 Prairial year V (20 May 1797). | ||||

François Barthélemy | ||||

| Barthélemy & Carnot proscribed and replaced after Coup of 18 Fructidor year V (4 Sept. 1797). | ||||

.JPG.webp) Philippe-Antoine Merlin de Douai |

.JPG.webp) François de Neufchâteau | |||

| Neufchâteau drawn by lot to be replaced 26 Floréal year VI (15 May 1798). | ||||

.jpg.webp) Jean-Baptiste Treilhard | ||||

| Rewbell drawn by lot to be replaced 27 Floréal year VII (16 May 1799). | ||||

Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès | ||||

| Compelled to resign, 30 Prairial year VII (18 June 1799). |

Compelled to resign, 30 Prairial year VII (18 June 1799). |

Treilhard's election annulled as irregular, 29 Prairial year VII (17 June 1799). | ||

.JPG.webp) Roger Ducos |

Jean-François-Auguste Moulin | .JPG.webp) Louis-Jérôme Gohier | ||

| After the Coup of 18 Brumaire (9 November 1799), Barras, Ducos & Sieyès resigned. Moulin & Gohier, refusing to resign, were arrested by General Moreau. | ||||

The Consulate

| The provisional Consuls (10 November – 12 December 1799) | ||

|---|---|---|

| With the Coup of 18 Brumaire in 1799, the Directory was abolished, and a provisional committee of three Consuls took power. | ||

|

|

.JPG.webp) |

| Napoleon Bonaparte | Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès | Roger Ducos |

| The Consuls (12 December 1799 – 18 May 1804) | ||

| With the Constitution of the Year VIII (December 1799), Bonaparte became First Consul for ten years, with two consuls appointed by him who had consultative voices only. With the Constitution of the Year X (August 1802), Bonaparte became First Consul for life, establishing a de facto dictatorship. | ||

|

.JPG.webp) |

|

| Napoleon Bonaparte First Consul |

J.J.R. de Cambacérès Second Consul |

Charles-François Lebrun Third Consul |

| Napoleon took the title Emperor of the French on 18 May 1804, ending the Consulate and establishing the First French Empire. | ||

House of Bonaparte, First Empire (1804–1814)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | .svg.png.webp) | Napoleon I, the Great (Napoléon Ier, le Grand) | 18 May 1804 | 11 April 1814[2] | Emperor of the French (Empereur des Français) |

Napoleon Bonaparte became Emperor in 1804 following a referendum. He received the title Emperor of the French to differentiate himself from the previous monarchs. His rule saw the domination of France as it crushed the Prussians, Russians, Austrians and British alike. Napoleon's rule lasted from 1804 to 1814 when after many coalitions against him he was defeated by the combined might of the other powers of Europe. He would then be exiled to the Island of Elba off the coast of Italy. However he was given the island to run as the Emperor of Elba.

Capetian Dynasty (1814–1815)

House of Bourbon, Bourbon Restoration (1814–1815)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| _(1).svg.png.webp) | Louis XVIII | 11 April 1814 | 20 March 1815 | • Grandson of Louis XV • Younger brother of Louis XVI[2] | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

House of Bonaparte, First Empire (Hundred Days, 1815)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessor | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | .svg.png.webp) | Napoleon I (Napoléon Ier) | 20 March 1815 | 22 June 1815[2] | None | Emperor of the French (Empereur des Français) |

| .svg.png.webp) | Napoleon II (Napoléon II) [n 1] | 22 June 1815 | 7 July 1815 | • Son of Napoleon I | Emperor of the French (Empereur des Français) |

Capetian Dynasty (1815–1848)

House of Bourbon (1815–1830)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessor | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| _(1).svg.png.webp) | Louis XVIII | 7 July 1815 | 16 September 1824[2] | • Grandson of Louis XV • Younger brother of Louis XVI | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

| _(1).svg.png.webp) | Charles X | 16 September 1824 | 2 August 1830 | • Grandson of Louis XV • Younger Brother of Louis XVI and Louis XVIII | King of France and of Navarre (Roi de France et de Navarre) |

Revolution of 1830

For a few days during the July Revolution, Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette held executive power and was offered the presidency of a Republic. He refused.

Louis XIX was technically king for 20 minutes on 2 August 1830, and his nephew Henri V for ten days after that.

House of Orléans, July Monarchy (1830–1848)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

_by_Winterhalter.jpg.webp) | .svg.png.webp) | Louis-Philippe I the Citizen King (Louis Philippe, le Roi Bourgeois) | 9 August 1830 | 24 February 1848 | • Sixth generation descendant of Louis XIII in the male line • Fifth cousin of Louis XVI, Louis XVIII and Charles X |

King of the French (Roi des Français) |

French Second Republic (1848–1852)

De facto heads of state of regimes of 1848

- Political parties

| No. | Portrait | Name (birth and death) |

Term of office | Political party | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provisional Government of the Republic | ||||||

| – |  |

Jacques-Charles Dupont de l'Eure (President of the Provisional Government) (1767–1855) |

24 February 1848 | 9 May 1848 | Moderate Republican | |

| His prestige and popularity prevented the heterogeneous republican coalition from having to immediately agree upon a common leader. Due to his great age (upon entering office, he was just a few days short of his 81st birthday), Dupont de l'Eure effectively delegated part of his duties to Minister of Foreign Affairs Alphonse de Lamartine. On 4 May, he resigned in order to make way for the Executive Commission, which he declined to join. | ||||||

| Executive Commission | ||||||

| – |  |

Executive Commission: | 9 May 1848 | 24 June 1848 | Moderate Republican | |

| In May 1848 the National Assembly decided to establish the Executive Commission as a form of collective presidency, similar to that of Year III in the first French Revolution. The members were chosen from prominent members of the former Provisional Government. These members acted jointly as head of state. The experiment was a failure and lasted slightly more than a month before chaos rocked Paris and much of the country. | ||||||

| Cavaignac Martial Law | ||||||

| – |  |

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac (Chief of the Executive Power) (1802–1857) |

28 June 1848 | 20 December 1848 | Moderate Republican | |

| On 24 June, the Executive Commission was defeated by a vote of no confidence and Cavaignac was granted full powers, making him France's de facto head of state and dictator. After laying down his dictatorial powers, he continued to preside over the Executive Committee till the election of a regular President of the Republic. | ||||||

President of the Republic

- Political parties

| No. | Portrait | Name (birth and death) |

Term of office (election year) |

Political party | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (1808–1873) |

20 December 1848 | 2 December 1852 | Bonapartiste | [28] |

| 1848 | ||||||

| Nephew of Napoléon I. Elected first President of the French Republic, in the 1848 election against Louis-Eugène Cavaignac. He provoked the French coup of 1851, and proclaimed himself Emperor of the French in 1852. | ||||||

House of Bonaparte, Second Empire (1852–1870)

| Portrait | Coat of arms | Name | From | Until | Relationship with his predecessors | Title |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| .svg.png.webp) | Napoleon III (Napoléon III) | 2 December 1852 | 4 September 1870 | • Nephew of Napoleon I[2] | Emperor of the French (Empereur des Français) |

French Third Republic (1870–1940)

President of the Government of National Defense

- Louis Jules Trochu (4 September 1870 – 13 February 1871)

Chief of the Executive Power

- Adolphe Thiers (17 February 1871 – 30 August 1871), became President on 31 August 1871

Presidents of the Republic

- Political parties

Independent

Moderate Monarchist

Opportunist Republican

Democratic Republican Alliance

Radical-Socialist Party

| No. | Portrait | Name (birth and death) |

Term of office | Political party | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 |  |

Adolphe Thiers (1797–1877) |

31 August 1871 | 24 May 1873 | Independent | [29] |

| Initially a moderate monarchist, named President following the adoption of the Rivet law. He became a Republican during his term, and resigned in the face of hostility from the Assemblée nationale, largely in favour of a return to monarchy. | ||||||

| 3 |  |

Patrice de Mac-Mahon, duc de Magenta (1808–1893) |

24 May 1873 | 30 January 1879 | Moderate Monarchist | [30] |

| A Marshal of France, he was the only monarchist (and only Duke) to serve as President of the Third Republic. He resigned shortly after the Republican victory in the 1877 legislative elections, following his decision to dissolve the Chamber of Deputies. During his term, the French Constitutional Laws of 1875 that served as the Constitution of the Third Republic were passed, and he therefore became the first president under the constitutional settlement that would last until 1940. | ||||||

| 4 |  |

Jules Grévy (1807–1891) |

30 January 1879 | 2 December 1887 | Opportunist Republican | [31] |

| The first president to complete a full term, he was easily re-elected in December 1885. He was nonetheless forced to resign, following an honours scandal in which his son-in-law was implicated. | ||||||

| 5 |  |

Marie François Sadi Carnot (1837–1894) |

3 December 1887 | 25 June 1894† | Opportunist Republican | [32] |

| His term was marked by boulangist unrest and the Panama scandals, and by diplomacy with Russia. †Assassinated (stabbed) by Sante Geronimo Caserio a few months before the end of his mandate, he is interred at the Panthéon, Paris. | ||||||

| 6 |  |

Jean Casimir-Perier (1847–1907) |

27 June 1894 | 16 January 1895 | Opportunist Republican | [33] |

| Perier's was the shortest Presidential term: he resigned after six months and 20 days. | ||||||

| 7 |  |

Félix Faure (1841–1899) |

17 January 1895 | 16 February 1899† | Opportunist Republican; Progressive Republican |

[34] |

| Pursued colonial expansion and ties with Russia. President during the Dreyfus Affair. †Four years into his term he died of apoplexy at the Élysée Palace, allegedly in flagrante. | ||||||

| 8 |  |

Émile Loubet (1838–1929) |

18 February 1899 | 18 February 1906 | Democratic Republican Alliance | [35] |

| During his seven-year term, the 1905 French law on the Separation of the Churches and the State was adopted, and only four Presidents of the Council succeeded to the Hôtel Matignon. He did not seek re-election at the end of his term. | ||||||

| 9 |  |

Armand Fallières (1841–1931) |

18 February 1906 | 18 February 1913 | Democratic Republican Party | [36] |

| President during the Agadir Crisis, when French troops first occupied Morocco. He was a party to the Triple Entente, which he strengthened by diplomacy. Like his predecessor, he did not seek re-election. | ||||||

| 10 |  |

Raymond Poincaré (1860–1934) |

18 February 1913 | 18 February 1920 | Democratic Republican Party | [37] |

| President during World War I. He subsequently served as President of the Council 1922–1924 and 1926–1929. | ||||||

| 11 |  |

Paul Deschanel (1855–1922) |

18 February 1920 | 21 September 1920 | Democratic Republican and Social Party | [38] |

| An intellectual elected to the Académie française, he overcame the popular Georges Clemenceau, to general surprise, in the January 1920 election. He resigned after eight months due to mental health problems. | ||||||

| 12 | .jpg.webp) |

Alexandre Millerand (1859–1943) |

23 September 1920 | 11 June 1924 | Independent | [39] |

| An "Independent Socialist" increasingly drawn to the right wing, he resigned after four years following the victory of the Cartel des Gauches in the 1924 legislative elections. | ||||||

| 13 |  |

Gaston Doumergue (1863–1937) |

13 June 1924 | 13 June 1931 | Radical-Socialist Party | [40] |

| The first Protestant President, he took a firm political stance against Germany and its resurgent nationalism. His seven-year term was marked by ministerial discontinuity. | ||||||

| 14 |  |

Paul Doumer (1857–1932) |

13 June 1931 | 7 May 1932† | Radical-Socialist Party | [41] |

| Elected in the second round of the 1931 election, having displaced the pacifist Aristide Briand. †Assassinated (shot) by the mentally unstable Paul Gorguloff. | ||||||

| 15 | .jpg.webp) |

Albert Lebrun (1871–1950) |

10 May 1932 | 11 July 1940 (de facto) |

Democratic Alliance | [42] |

| Re-elected in 1939, his second term was interrupted de facto by the rise to power of Marshal Philippe Pétain. | ||||||

Acting Presidents

Under the Third Republic, the President of the Council served as acting president whenever the office of president was vacant.

- Jules Armand Dufaure (30 January 1879)

- Maurice Rouvier (2–3 December 1887)

- Charles Dupuy (25–27 June 1894, 16–17 January 1895 and 16–18 February 1899)

- Alexandre Millerand (21–23 September 1920)

- Frédéric François-Marsal (11–13 June 1924)

- André Tardieu (7–10 May 1932)

The office of President of the French Republic did not exist from 1940 until 1947.

French State (1940–1944)

Chief of State

| No. | Portrait | Name (birth and death) |

Term of office | Political party | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | .jpg.webp) |

Philippe Pétain (1856–1951) |

11 July 1940 | 19 August 1944 | Independent | |

| Pétain was Chief of the French State from 1940 to 1944. An elder authoritarian military leader, Pétain issued fascist, clerical and antisemitic laws under Nazi Germany's supervisions. After the liberation of France in 1944, Pétain was imprisoned for life. | ||||||

Provisional Government of the French Republic (1944–1947)

| Portrait | Name (Birth–Death) |

Term of office | Political Party (Political Coalition) |

Legislature (Election) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 59 |  |

Charles de Gaulle (1890–1970) |

1 | 20 August 1944 | 26 January 1946 | Independent | Provisional |

| 2 | I (1945) | ||||||

| 60 |  |

Félix Gouin (1884–1977) |

• | 26 January 1946 | 24 June 1946 | French Section of the Workers' International (Tripartisme) | |

| 61 |  |

Georges Bidault (1899–1983) |

1 | 24 June 1946 | 28 November 1946 | Popular Republican Movement (Tripartisme) |

II (June 1946) |

| – | .jpg.webp) |

Vincent Auriol (1884–1966) (interim) |

– | 28 November 1946 | 16 December 1946 | French Section of the Workers' International (Tripartisme) |

IV Rep. I (Nov.1946) |

| 62 |  |

Léon Blum (1872–1950) |

3 | 16 December 1946 | 22 January 1947 | French Section of the Workers' International (Tripartisme) | |

French Fourth Republic (1947–1958)

Presidents

Political parties: Socialist (SFIO) Centre-right (CNIP)

| No. | Portrait | Name (birth and death) |

Term of office (election year) |

Political party | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 |  |

Vincent Auriol (1884–1966) |

16 January 1947 | 16 January 1954 | French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) | [43] |

| 1947 | ||||||

| First President of the Fourth Republic; his term was marked by the First Indochina War. | ||||||

| 17 |  |

René Coty (1882–1962) |

16 January 1954 | 8 January 1959 | National Centre of Independents and Peasants (CNIP) | [44] |

| 1953 | ||||||

| Presidency marked by the Algerian War; appealed to Charles de Gaulle to resolve the May 1958 crisis. Following the promulgation of the Fifth Republic, he resigned after five years as president, giving way to De Gaulle. Technically, he is the first President of the Fifth Republic since he resigned after its establishment. | ||||||

Fifth French Republic (1958–present)

Presidents

Political parties: Socialist (PS) Christian-Centrist (CD) Republican (FNRI; PR) Gaullist (UNR; UDR; RPR) Neo-Gaullist (UMP) Centrist (REM)

| No. | Portrait | Name (birth and death) |

Term of office (election year) |

Political party | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18 | -(d).jpg.webp) |

Charles de Gaulle (1890–1970) |

8 January 1959 | 28 April 1969 | Union for the New Republic (UNR) until 1967 Union of Democrats for the Fifth Republic (UDR) from 1967 |

[45] |

| 1958, 1965 | ||||||

| Leader of the Free French Forces (1940–1944). President of the Provisional Government (1944–1946). Appointed President of the Council by René Coty in May 1958, to resolve the crisis of the Algerian War. He adopted a new Constitution, thus founding the Fifth Republic. Easily elected president in the 1958 election by electoral college, he took office the following month; he was re-elected by universal suffrage in the 1965 election. In 1966, he withdrew France from NATO integrated military command, and expelled the American bases on French soil. Having refused to step down during the crisis of May 1968, resigned following the failure of the 1969 referendum on regionalisation. | ||||||

| — |  |

Alain Poher (interim) (1909–1996) |

28 April 1969 | 20 June 1969 | Democratic Centre (CD) | [46] |

| Interim President, as President of the Senate. Defeated by Georges Pompidou in the second round of the 1969 election. | ||||||

| 19 |  |

Georges Pompidou (1911–1974) |

20 June 1969 | 2 April 1974† | Union of Democrats for the Republic (UDR) | [47] |

| 1969 | ||||||

| Prime Minister under Charles de Gaulle (1962–1968). Elected President in the 1969 election against the centrist Alain Poher. Favoured European integration. Supported economic modernisation and industrialisation. Faced the 1973 oil crisis. †Died in office of Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, two years before the end of his mandate. | ||||||

| — |  |

Alain Poher (interim) (1909–1996) |

2 April 1974 | 27 May 1974 | Democratic Centre (CD) | [46] |

| Interim President again, as President of the Senate. Did not stand against Valéry Giscard d'Estaing in the 1974 election. | ||||||

| 20 | .jpg.webp) |

Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (1926–2020) |

27 May 1974 | 21 May 1981 | Independent Republicans (RI) until 1977 Republican Party (PR) from 1977 |

[48] |

| 1974 | ||||||

| Founder of the FNRI and later the UDF in his efforts to unify the centre-right, he served in several Gaullist governments. Narrowly elected in the 1974 election, he instigated numerous reforms, including the lowering of the age of civil majority from 21 to 18, and the legalisation of abortion. He soon faced a global economic crisis and rising unemployment. Although the polls initially gave him a lead, he was defeated in the 1981 election by François Mitterrand, partly due to the disunion within the right wing. | ||||||

| 21 | .jpg.webp) |

François Mitterrand (1916–1996) |

21 May 1981 | 17 May 1995 | Socialist Party (PS) | [49] |

| 1981, 1988 | ||||||

| Candidate of a united left-wing ticket in the 1965 election, he founded the Socialist Party in 1971. Having narrowly lost the 1974 election, he was finally elected in the 1981 election. He instigated several reforms (abolition of the death penalty, a fifth week of paid leave for employees). After the right-wing victory in the 1986 legislative elections, he named Jacques Chirac Prime Minister, thus beginning the first cohabitation. Re-elected in the 1988 election against Chirac, he was again forced to cohabit with Édouard Balladur following the 1993 legislative elections. He retired in 1995 after the conclusion of his second term. He was the first president elected twice by universal suffrage, he was the first left-wing President of the Fifth Republic, and his presidential tenure was the longest of the Fifth Republic. | ||||||

| 22 |  |

Jacques Chirac (1932–2019) |

17 May 1995 | 16 May 2007 | Rally for the Republic (RPR) until 2002 Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) from 2002 |

[50] |

| 1995, 2002 | ||||||

| Prime Minister (1974–1976); on resignation, founded the RPR. Eliminated in the first round of the 1981 election, he again served as Prime Minister (1986–1988). Beaten in the 1988 election, he was elected in the 1995 election. He engaged in social reforms to counter "social fracture". In 1997, he dissolved the Assemblée nationale; a left-wing victory in the 1997 legislative elections, forced him to name Lionel Jospin Prime Minister for a five-year cohabitation. Presidential terms reduced from seven to five years. In 2002, he was re-elected against the leader of the extreme right-wing Jean-Marie Le Pen. Opposed the Iraq War. He did not run in 2007, he retired from political life and returned to the Conseil constitutionnel. | ||||||

| 23 |  |

Nicolas Sarkozy (1955–) |

16 May 2007 | 15 May 2012 | Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) | [51] |

| 2007 | ||||||

| Served in numerous ministerial posts 1993–1995 and 2002–2007. Leader of the UMP since 2004. In the 2007 election, he topped the first round poll, and was elected in the second round against Ségolène Royal. Soon after taking office, he introduced the French fiscal package of 2007 and other laws to counter illegal immigration and recidivism. President of the Council of the EU in 2008, he defended the Treaty of Lisbon and mediated in the South Ossetia War; at national level, he had to deal with the financial crisis and its consequences. Following the 2008 constitutional reform, he became the first president since Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte to address the Versailles Congress on 22 June 2009. President of the G8 and the G20 in 2011. Defeated in the 2012 election. | ||||||

| 24 | .jpg.webp) |

François Hollande (1954–) |

15 May 2012 | 14 May 2017 | Socialist Party (PS) | [52] |

| 2012 | ||||||

| Served as a member of the National Assembly for Corrèze's 1st constituency (1988–1993; 1997) and as First Secretary of the Socialist Party (1997–2008). He was Mayor of Tulle (2001–2008), and President of the Corrèze General Council (2008–2012). The second left-wing President of the Fifth Republic. Elected in the 2012 election, defeating Nicolas Sarkozy. Chose not to run for reelection in the 2017 election due to historically low approval ratings brought on by high unemployment and other economic factors. | ||||||

| 25 |  |

Emmanuel Macron (1977–) |

14 May 2017 | Incumbent | La République En Marche! (REM) | |

| 2017, 2022 | ||||||

| Served as Deputy Secretary General of the Élysée (2012–2014), Minister of the Economy, Industry and Digital Affairs (2014–2016). Elected in the 2017 election, defeating Marine Le Pen (FN). | ||||||

Later pretenders

Various pretenders descended from the preceding monarchs have claimed to be the legitimate monarch of France, rejecting the claims of the President of France, and of each other. These groups are:

- Legitimist claimants to the throne of France: descendants of the Bourbons, rejecting all heads of state 1792–1814, 1815, and since 1830. Unionists recognized the Orléanist claimant after 1883.

- Legitimist-Anjou claimants to the throne of France: descendants of Louis XIV, claiming precedence over the House of Orléans by virtue of primogeniture

- Orléanist claimants to the throne of France: descendants of Louis-Phillippe, himself descended from a junior line of the Bourbon dynasty, rejecting all heads of state since 1848.

- Bonapartist claimants to the throne of France: descendants of Napoleon I and his brothers, rejecting all heads of state 1815–48, and since 1870.

- English claimants to the throne of France: Kings of England and later, of Great Britain (renounced by Hanoverian King George III upon union with Ireland)

- Jacobite claimants to the throne of France: senior heirs-general of King Edward III of England and thus his claim to the French throne, also claiming England, Scotland, and Ireland.

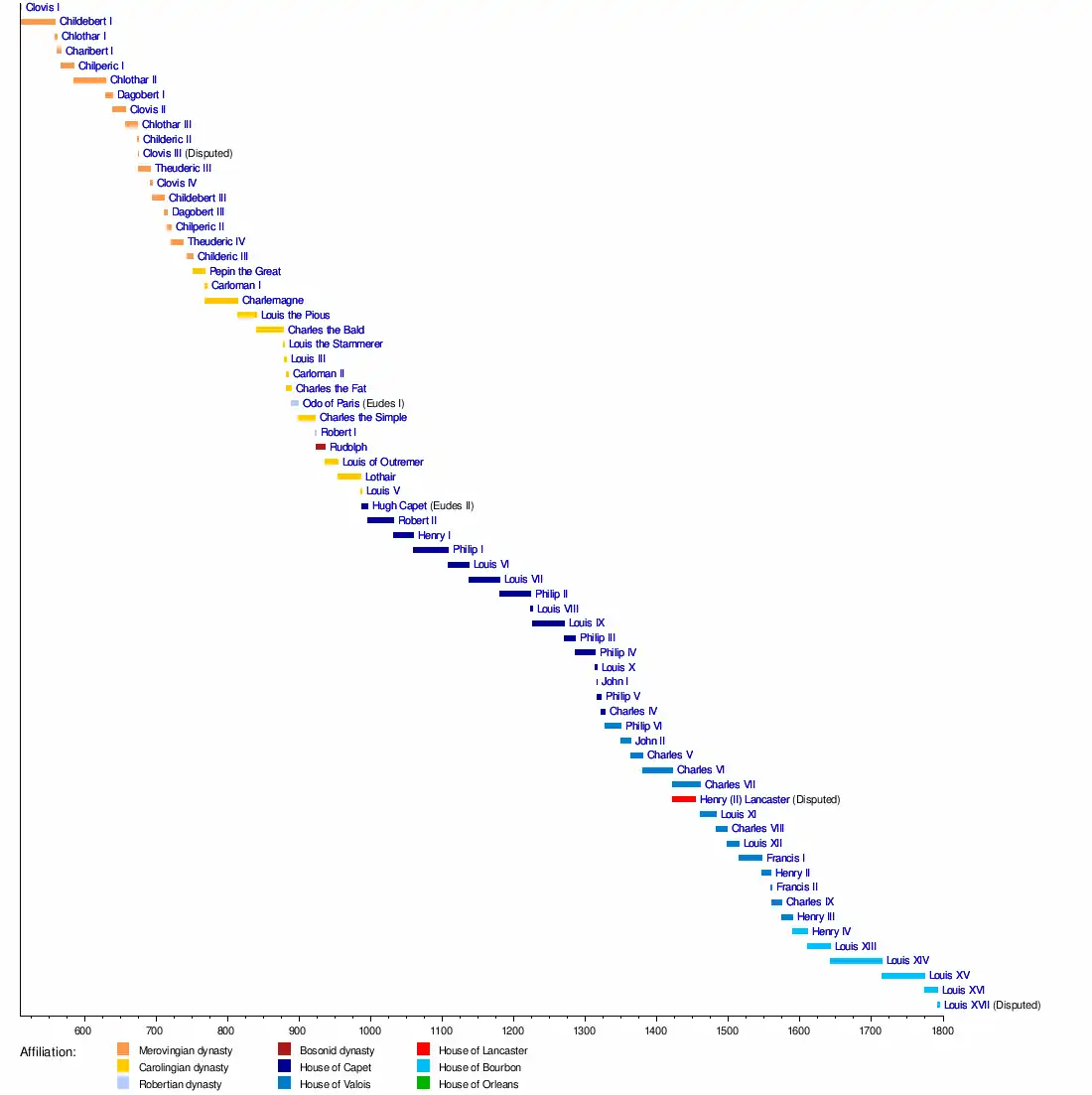

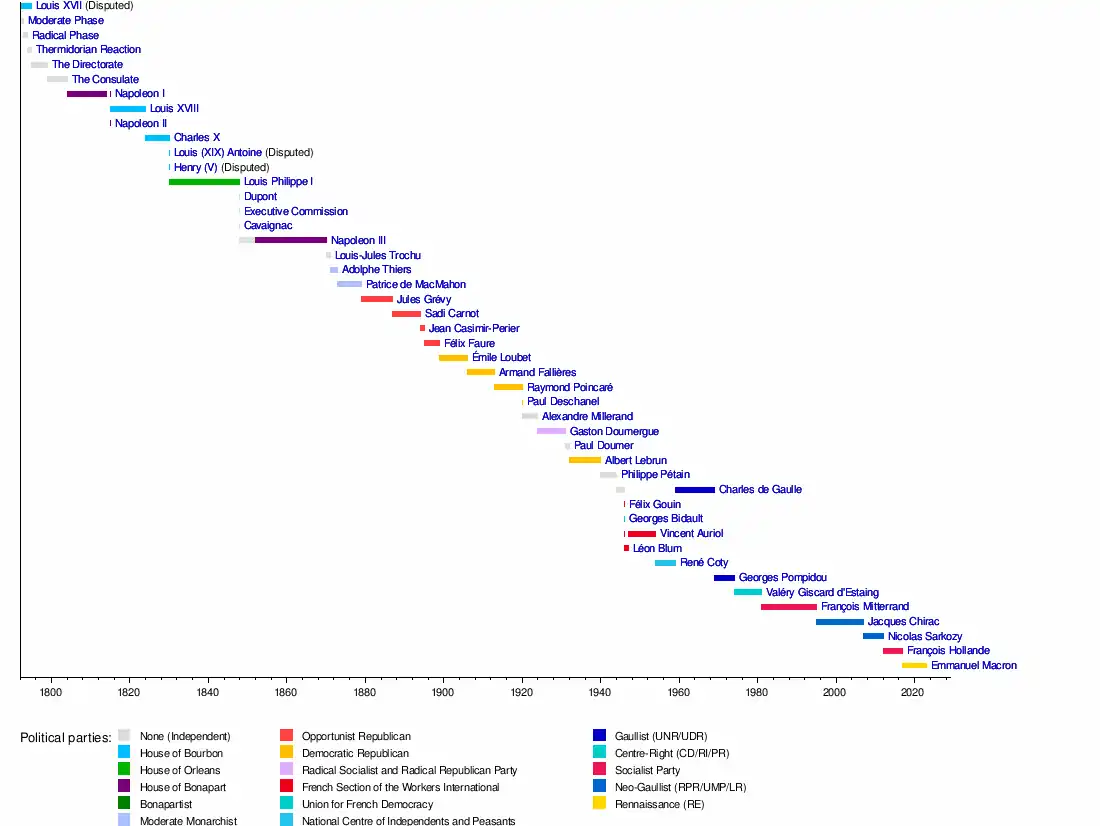

Timeline

509 - 1795

1792 - Present

See also

- List of French monarchs

- List of presidents of the National Convention

- List of presidents of France

- Ministers of the French National Convention

- Representative on mission

- Full list of members of the Convention per department: List of members of the National Convention by Department (French)

- List of foreign ministers of France

- List of prime ministers of France

- President of France

- British claims to the French throne

- Kings of France family tree

- Style of the French sovereign

Notes, citations and sources

Notes

- From 22 June to 7 July 1815, Bonapartists considered Napoleon II as the legitimate heir to the throne, his father having abdicated in his favor. However, throughout this period he resided in Austria, with his mother. Louis XVIII was reinstalled as king on 7 July

- From 9 Apr 1793 to 18 Apr 1793 the functions of president were exercised by vice-president Jacques-Alexis Thuriot de la Rosière. He was elected president in his own right for the fortnight 27 June 1793 – 11 July 1793

- The name Thermidorian refers to 9 Thermidor Year II (27 July 1794), the date according to the French Revolutionary Calendar when Robespierre and other radical revolutionaries came under concerted attack in the National Convention. Thermidorian Reaction also refers to the remaining period until the National Convention was superseded by the Directory; this is also sometimes called the era of the Thermidorian Convention. Prominent figures of Thermidor include Paul Barras, Jean-Lambert Tallien, and Joseph Fouché. Neely, pp. 225–227.

References

- Brown, Peter (2003). The Rise of Western Christendom. Malden, MA, USA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd. p. 137.

- Hansen, M.H., ed. (1967). Kings, Rulers, and Statesmen. NY, USA: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. pp. 103–107.

- Babcock, Philip (1993). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. MA, USA: Merriam-Webster. p. 341.

- Gwatking, H. M.; Whitney, J. P.; et al. (1930). Cambridge Medieval History: Germany and the Western Empire. Vol. III. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Parisse, Michael (2005). "Lotharingia". In Reuter, T. (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 900–c. 1024. Vol. III. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 313–315.

- Knecht, Robert (2004). The Valois: Kings of France 1328–1422. NY, USA: Hambledon Continuum. pp. ix–xii. ISBN 1852854200.

- William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 2nd edition, Oxford University Press, 1990, here. See also Frank E. Smitha, Macrohistory: Fear, Overreaction and War (1792–93). 2009–2015 version. Accessed 21 April 2015.

- Doyle, p. 194.

- Editors, National Convention, Britannica.com, 2015, Accessed 22 April 2014.

- Roger Dupuy, La République jacobine. Terreur, guerre et gouvernement révolutionnaire (1792—1794). Paris, Le Seuil, 2005, pp. 28–34.

- Pierre-Dominique Cheynet, France: Members of the Executive Directory: 1793–1795, Archontology.org 2013, Accessed 19 February 2015.

- Jeremy D. Popkin, A Short History of the French Revolution, 5th ed. Pearson, 2009, pp. 72–77.

- Marisa Linton, Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship, and Authenticity in the French Revolution. (Oxford U.P., 2013), 174–75.

- Terror, Reign of; Britannica.com

- Donald Greer, The Incidence of the Terror during the French Revolution: A Statistical Interpretation, Cambridge (United States C.A), Harvard University Press, 1935

- Hector Fleischmann, Behind the Scenes in the Terror, Brentano's, 1915, pp. 129. and (in French) Garnier, Jean-Claude Garnier; Jean-Pierre Mohen. Cimetières autour du monde : Un désir d'éternité. Editions Errance. 2003, p. 191.

- J.M.Thompson, The French Revolution. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1959, p. 315.

- Pierre-Dominique Cheynet, France: Members of the Executive Directory: 1791–1792, Archontology.org 2013, Accessed 19 February 2015.

- François Furet, The French Revolution: 1770–1814, Oxford, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1996, p. 127.

- Thompson, p. 370.

- Robert J. Alderson, This Bright Era of Happy Revolutions: French Consul Michel-Ange-Bernard Mangourit and International Republicanism in Charleston, 1792–1794. U. of South Carolina Press, 2008, pp. 9–10.

- Sylvia Neely, A Concise History of the French Revolution, NY, Rowman & Littlefield, 2008, pp. 225–227.

- President of the Committee of Public Safety

- Informal President of the Committee of Public Safety, but also leading person in the National Convention. De facto, dictator in 1793–1794.

- Anchel, Robert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 03 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 933–934.

- Cheynet, Pierre-Dominique (2013). "France: Presidents of the Executive Directory: 1795-1799". Archontology.org. Retrieved 16 November 2013.

- Lefebvre & Soboul, p. 199.

- "Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte (1808–1873)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Adolphe Thiers (1797–1877)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Patrice de Mac-Mahon (1808–1893)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Jules Grévy (1807–1891)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Marie-François-Sadi Carnot (1837–1894)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Jean Casimir-Perier (1847–1907)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Félix Faure (1841–1899)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Emile Loubet (1836–1929)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Armand Fallières (1841–1931)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Raymond Poincaré (1860–1934)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Paul Deschanel (1855–1922)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Alexandre Millerand (1859–1943)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Gaston Doumergue (1863–1937)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Paul Doumer (1857–1932)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Albert Lebrun (1871–1950)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Vincent Auriol (1884–1966)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "René Coty (1882–1962)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Charles de Gaulle (1890–1970)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Alain Poher (1909–1996)" (in French). Official website of the French Presidency. 14 January 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Georges Pompidou (1911–1974)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Valéry Giscard d'Estaing (1926)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "François Mitterrand (1916–1996)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Jacques Chirac (1932)". Official website of the French Presidency. 15 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Nicolas Sarkozy (1955)". Official website of the French Presidency. 21 January 2019. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- "Biographie officielle de François Hollande" [Official biography of François Hollande]. Official website of the French Presidency. 22 November 2018. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

Sources

- Alderson, Robert. This Bright Era of Happy Revolutions: French Consul. U. of South Carolina Press, 2008. OCLC 192109705

- Anchel, Robert (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 07 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 46.

- Doyle, William. The Oxford History of the French Revolution. 2nd edition. Oxford University Press, 2002. OCLC 490913480

- Cheynet, Pierre-Dominique. France: Members of the Executive Directory: 1792–1793, and 1793–1795. Archontology.org 2013, Accessed 19 February 2015.

- (in French) Dupuy, Roger. La République jacobine. Terreur, guerre et gouvernement révolutionnaire (1792—1794). Paris, Le Seuil, 2005. ISBN 2-02-039818-4

- Furet, François. The French Revolution: 1770–1814. Oxford, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 1996. OCLC 25094935

- Fleischmann, Hector, Behind the Scenes in the Terror, NY, Brentano's, 1915. OCLC 499613

- (in French) Garnier, Jean-Claude; Jean-Pierre Mohen. Cimetières autour du monde: Un désir d'éternité. Paris, Editions Errance. 2003. OCLC 417420035

- Greer, Donald. The Incidence of the Terror during the French Revolution: A Statistical Interpretation. Cambridge (United States C.A), Harvard University Press, 1951. OCLC 403511

- Linton, Marisa. Choosing Terror: Virtue, Friendship, and Authenticity in the French Revolution Oxford U.P., 2013. OCLC 829055558

- Neeley, Sylvia. A Concise History of the French Revolution, Lanham, Rowman & Littlefield, 2008. OCLC 156874791

- Popkin, Jeremy D. A Short History of the French Revolution. 5th ed. Upper Saddle River, Pearson, 2009. OCLC 36739547

- Smitha, Frank E. Macrohistory: Fear, Overreaction and War (1792–93). 2009–2015 version. Accessed 21 April 2015.

- Thompson, J.M. The French Revolution. Oxford, Basil Blackwell, 1959. OCLC 1052771