French Resistance

The French Resistance (French: La Résistance) was a collection of groups that fought the Nazi occupation of France and the collaborationist Vichy régime in France during the Second World War. Resistance cells were small groups of armed men and women (called the Maquis in rural areas)[2][3] who conducted guerrilla warfare and published underground newspapers. They also provided first-hand intelligence information, and escape networks that helped Allied soldiers and airmen trapped behind Axis enemy lines. The Resistance's men and women came from many different parts of French society, including émigrés, academics, students, aristocrats, conservative Roman Catholics (including clergy), Protestants, Jews, Muslims, liberals, anarchists, communists, and some fascists. The proportion of French people who participated in organized resistance has been estimated at from one to three percent of the total population.[4]

| French Resistance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Resistance during World War II | |||||

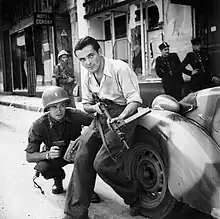

An American officer and a French partisan in 1944 | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

| ||||

| Units involved | |||||

| Part of a series on |

| Anti-fascism |

|---|

|

The French Resistance played a significant role in facilitating the Allies' rapid advance through France following the invasion of Normandy on 6 June 1944. Members provided military intelligence on German defences known as the Atlantic Wall, and on Wehrmacht deployments and orders of battle for the Allies' invasion of Provence on 15 August. The Resistance also planned, coordinated, and executed sabotage acts on electrical power grids, transport facilities, and telecommunications networks.[5][6] The Resistance's work was politically and morally important to France during and after the German occupation. The actions of the Resistance contrasted with the collaborationism of the Vichy régime.[7][8]

After the Allied landings in Normandy and Provence, the paramilitary components of the Resistance formed a hierarchy of operational unita known as the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) with around 100,000 fighters in June 1944. By October 1944, the FFI had grown to 400,000 members.[9] Although the amalgamation of the FFI was sometimes fraught with political difficulties, it was ultimately successful, and allowed France to rebuild the fourth-largest army in the European theatre (1.2 million men) by VE Day in May 1945.[10]

Nazi occupation

After the Battle of France and the second French-German armistice, the lives of the French continued unchanged at first. The German occupation authorities and the Vichy régime became increasingly brutal and intimidating. Most civilians remained neutral, but both the occupation of French territory[14][15] and German policy inspired the formation of paramilitary groups dedicated to both active and passive resistance.[16]

One of the conditions of the armistice was that the French must pay for their own occupation. This amounted to about 20 million German Reichsmarks per day, a sum that, in May 1940, was approximately equivalent to four hundred million French francs.[17] The artificial exchange rate of the Reichsmark versus the franc had been established as one mark to twenty francs.[17][18] Due to the overvaluation of German currency, the occupiers were able to make seemingly fair and honest requisitions and purchases while operating a system of organized plunder. Prices soared,[19] leading to widespread food shortages and malnutrition,[20] particularly among children, the elderly, and members of the working class engaged in physical labour.[21] Labour shortages also plagued the French economy because hundreds of thousands of French workers were requisitioned and transferred to Germany for compulsory labour under the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO).[2][22][23]

The labour shortage was worsened by the large number of French prisoners of war held in Germany.[24] Beyond these hardships and dislocations, the occupation became increasingly unbearable. Regulations, censorship, propaganda and nightly curfews all played a role in establishing an atmosphere of fear and repression.[18] French women consorting with German soldiers angered many French men, though often the women had to do so to acquire food for themselves and their families.[25][26]

As reprisals for Resistance activities, the authorities established harsh forms of collective punishment. For example, the Soviet resistance in August 1941 led to thousands of hostages taken from the population.[27] A typical policy statement read, "After each further incident, a number, reflecting the seriousness of the crime, shall be shot."[28] During the occupation, an estimated 30,000 French civilian hostages were shot to intimidate others who were involved in acts of resistance.[29] German troops occasionally engaged in massacres such as the Oradour-sur-Glane massacre, in which an entire village was razed and almost every resident murdered because of persistent resistance in the vicinity.[30][31]

In early 1943, the Vichy authorities created a paramilitary group, the Milice (militia), to combat the Resistance. This group worked alongside German forces that, by the end of 1942, were stationed throughout France.[32] The group collaborated closely with the Nazis, similar to the Gestapo security forces in Germany.[33] Their actions were often brutal and included torture and execution of Resistance suspects. After the liberation of France in the summer of 1944, the French executed many of the estimated 25,000 to 35,000 miliciens[32] for their collaboration with the Nazis. Many of those who escaped arrest fled to Germany, where they were incorporated into the Charlemagne Division of the Waffen SS.[34]

History

1940: Initial shock, and counteraction

The experience of the Occupation was hard to be accepted by the French. Many Parisians could not get over the shock experienced when they first saw the huge swastika flags hanging over the Hôtel de Ville and on top of the Eiffel Tower.[35] At the Palais-Bourbon, where the National Assembly building was converted into the office of the Kommandant von Gross-Paris, a huge banner was spread across the facade of the building reading in capital letters: "DEUTSCHLAND SIEGT AN ALLEN FRONTEN!" ("Germany is victorious on all fronts!"), a sign that is mentioned by virtually all accounts by Parisians at the time.[36] The résistant Henri Frenay wrote about seeing the tricolour flag disappear from Paris with the swastika flag flying in its place and German soldiers standing guard in front of buildings that once housed the institutions of the republic gave him "un sentiment de viol" ("a feeling of rape").[37] The British historian Ian Ousby wrote:

Even today, when people who are not French or did not live through the Occupation look at photos of German soldiers marching down the Champs Élysées or of Gothic-lettered German signposts outside the great landmarks of Paris, they can still feel a slight shock of disbelief. The scenes look not just unreal, but almost deliberately surreal, as if the unexpected conjunction of German and French, French and German, was the result of a Dada prank and not the sober record of history. This shock is merely a distant echo of what the French underwent in 1940: seeing a familiar landscape transformed by the addition of the unfamiliar, living among everyday sights suddenly made bizarre, no longer feeling at home in places they had known all their lives."[38]

Ousby wrote that by the end of summer of 1940: "And so the alien presence, increasingly hated and feared in private, could seem so permanent that, in the public places where daily life went on, it was taken for granted".[39] At the same time, France was also marked by disappearances as buildings were renamed, books banned, art was stolen to be taken to Germany and people started to disappear as under the armistice of June 1940, the French were obliged to arrest and deport to the Reich those Germans and Austrians who fled to France in the 1930s.[40]

Resistance when it first began in the summer of 1940 was based upon what the writer Jean Cassou called refus absurde ("absurd refusal") of refusing to accept that the Reich would win and even if it did, it was better to resist.[41] Many résistants often spoke of some "climax" when they saw some intolerable act of injustice, after which they could no longer remain passive.[42] The résistant Joseph Barthelet told the British SOE agent George Miller that his "climax" occurred when he saw the German military police march a group of Frenchmen, one of whom was a friend, into the Feldgendarmerie in Metz.[42] Barthelt recalled: "I recognized him only by his hat. Only by his hat, I tell you and because I was waiting on the roadside to see him pass. I saw his face all right, but there was no skin on it, and he could not see me. Both his poor eyes had been closed into two purple and yellow bruises".[42] The right-wing résistant Henri Frenay who had initially sympathized with the Révolution nationale stated that when he saw the German soldiers in Paris in the summer of 1940, he knew he had to do something to uphold French honor because of the look of contempt he saw on the faces of the Germans when viewing the French.[42] In the beginning, resistance was limited to activities such as severing phone lines, vandalizing posters and slashing tyres on German vehicles.[43] Another form of resistance was underground newspapers like Musée de l'Homme (Museum of Mankind) which circulated clandestinely.[44] The Musée de l'Homme was founded by two professors, Paul Rivet and the Russian émigré Boris Vildé in July 1940.[45] In the same month, July 1940, Jean Cassou founded a resistance group in Paris while the liberal Catholic law professor François de Menthon founded the group Liberté in Lyon.[45]

On 19 July 1940 the Special Operations Executive (SOE) was founded in Britain with orders from Churchill to "set Europe ablaze".[46] The F Section of the SOE was headed by Maurice Buckmaster and provided invaluable support for the resistance.[46] From May 1941, Frenay founded Combat, one of the first Resistance groups. Frenay recruited for Combat by asking people such questions as whether they believed that Britain would not be defeated and if they thought a German victory was worth stopping, and based on the answers he received would ask those whom he thought were inclined to resistance: "Men are already gathering in the shadows. Will you join them?".[44] Frenay, who was to emerge as one of the leading resistance chefs, later wrote: "I myself never attacked a den of collaborators or derailed trains. I never killed a German or a Gestapo agent with my own hand".[43] For security reasons, Combat was divided into a series of cells that were unaware of each other.[44] Another early resistance group founded in the summer of 1940 was the ill-fated Interallié group led by a Polish émigré Roman Czerniawski that passed on intelligence from contacts in the Deuxième Bureau to Britain via couriers from Marseilles. A member of the group, Frenchwoman Mathilde Carré codenamed La Chatte (the cat), was later arrested by the Germans and betrayed the group.[47]

The French intelligence service, the Deuxième Bureau stayed loyal to the Allied cause despite nominally being under the authority of Vichy; the Deuxième Bureau continued to collect intelligence on Germany, maintained links with British and Polish intelligence and kept the secret that before World War II Polish intelligence had devised a method via a mechanical computer known as the Bombe to break the Enigma machine that was used to code German radio messages.[48] A number of the Polish code-breakers who developed the Bombe machine in the 1930s continued to work for the Deuxième Bureau as part of the Cadix team breaking German codes.[48] In the summer of 1940, many cheminots (railroad workers) engaged in impromptu resistance by helping French soldiers wishing to continue the struggle together with British, Belgian and Polish soldiers stranded in France escape from the occupied zone into the unoccupied zone or Spain.[49] Cheminots also became the main agents for delivering underground newspapers across France.[49]

The first résistant executed by the Germans was a Polish Jewish immigrant named Israël Carp, shot in Bordeaux on 28 August 1940 for jeering a German military parade down the streets of Bordeaux.[50] The first Frenchman shot for resistance was 19 year-old Pierre Roche, on 7 September 1940 after he was caught cutting the phone lines between Royan and La Rochelle.[50] On 10 September 1940, the military governor of France, General Otto von Stülpnagel announced in a press statement that no mercy would be granted to those engaging in sabotage and all saboteurs would be shot.[50] Despite his warning, more continued to engage in sabotage. Louis Lallier, a farmer, was shot for sabotage on 11 September in Épinal, and Marcel Rossier, a mechanic, was shot in Rennes on 12 September.[50] One more was shot in October 1940, and three more in November 1940.[50]

Starting in the summer of 1940 anti-Semitic laws started to come into force in both the occupied and unoccupied zones.[51] On 3 October 1940 Vichy introduced the law on the status of Jews, banning Jews from numerous professions including the law, medicine and public service.[51] Jewish businesses were "Aryanized" by being placed in the hands of "Aryan" trustees who engaged in the most blatant corruption while Jews were banned from cinemas, music halls, fairs, museums, libraries, public parks, cafes, theatres, concerts, restaurants, swimming pools and markets.[52] Jews could not move without informing the police first, own radios or bicycles, were denied phone service, could not use phone booths marked Accès interdit aux Juifs and were only allowed to ride the last carriage on the Paris Metro.[53] The French people at the time distinguished between Israélites (a polite term in French) who were "properly" assimilated French Jews and the Juifs (formerly a derogatory term in French, nowadays the standard name for Jewish people) who were the "foreign" and "unassimilated" Jews who were widely seen as criminals from abroad living in slums in the inner cities of France.[54] All through the 1930s, the number of illegal Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe was vastly exaggerated, and popular opinion believed that the majority of Jews living in France were illegal immigrants who were causing all sorts of social problems.[55] In a context where the number of Jews in France, and even more so the number of illegal Jewish immigrants were much exaggerated, Ousby noted about the introduction of the first anti-Semitic laws in 1940: "There was no sign of public opposition to what was happening, or even widespread unease at the direction in which events were heading ... Many people, perhaps even most people, were indifferent. In the autumn of 1940 they had other things to think about; later they could find little room for fellow-feeling or concern for the public good in their own struggle to survive. What happened to the Jews were a secondary matter; it was beyond their immediate affairs, it belonged to that realm of the 'political' which they could no longer control or even bring themselves to follow with much interest".[56]

From the beginning, the Resistance attracted people from all walks of life and with diverse political views.[42] A major problem for the Resistance was that, with the exception of a number of Army officers who chose to go underground together with veterans of the Spanish Civil War, nobody had any military experience.[57] About 60,000 Spanish Republican emigres fought in the Resistance.[46] A further difficulty was the shortage of weapons, which explained why early resistance groups founded in 1940 focused on publishing journals and underground newspapers as the lack of guns and ammunition made armed resistance almost impossible.[58] Although officially adhering to the Comintern instructions not to criticise Germany because of the Soviet non-aggression pact with Hitler, in October 1940 the French Communists founded the Special Organisation (OS), composed with many veterans from the Spanish Civil War, which carried out a number of minor attacks before Hitler broke the treaty and invaded Russia.[59]

Life in the Resistance was highly dangerous and it was imperative for good "resistants" to live quietly and never attract attention to themselves.[60] Punctuality was key to meetings in public as the Germans would arrest anyone who was seen hanging around in public as if waiting for someone.[61] A major difficulty for the Resistance was the problem of denunciation.[62] Contrary to popular belief, the Gestapo was not an omnipotent agency with its spies everywhere, but instead the Gestapo relied upon ordinary people to volunteer information. According to Abwehr officer Hermann Tickler, the Germans needed 32 000 indicateurs (informers) to crush all resistance in France, but he reported in the fall of 1940 that the Abwehr had already exceeded that target.[62] It was difficult for Germans to pass themselves off as French, so the Abwehr, the Gestapo and the SS could not have functioned without French informers. In September 1940, the poet Robert Desnos published an article titled "J'irai le dire à la Kommandantur" in the underground newspaper Aujourd'hui appealing to ordinary French people to stop denouncing each other to the Germans.[43] Desnos's appeal failed, but the phrase "J'irai le dire à la Kommandantur" ("I'll go and tell the Germans about it") was a very popular one in occupied France as hundreds of thousands of ordinary French people denounced one another to the Germans.[62] The problem of informers, whom the French called indics or mouches, was compounded by the writers of poison pen letters or corbeaux.[62] These corbeaux were inspired by motivations such as envy, spite, greed, anti-Semitism, and sheer opportunism, as many ordinary French people wanted to ingratiate themselves with what they believed to be the winning side.[63] Ousby noted "Yet perhaps the most striking testimony to the extent of denunciation came from the Germans themselves, surprised at how ready the French were to betray each other".[64] In occupied France, one had to carry at all times a huge cache of documents such as an ID card, a ration card, tobacco voucher (regardless if one was a smoker or not), travel permits, work permits, and so on.[61] For these reasons, forgery became a key skill for the resistance as the Germans regularly required the French to produce their papers, and anyone whose papers seemed suspicious would be arrested.[61]

As the franc was devalued by 20% to the Reichsmark, which together with German policies of food requisition both to support their own army and the German home front, "France was slowly being bled dry by the outflow not just of meat and drink, fuel and leather, but of wax, frying pans, playing cards, axe handles, perfume and a host of other goods as well. Parisians, at least, had got the point as early as December 1940. When Hitler shipped back the Duc de Reichstadt's remains for a solemn burial in Les Invalides, people said they would have preferred coal rather than ashes."[65] People could not legally buy items without a ration book with the population being divided into categories A, B, C, E, J, T and V; among the products rationed included meat, milk, butter, cheese, bread, sugar, eggs, oil, coffee, fish, wine, soap, tobacco, salt, potatoes and clothing.[66] The black market flourished in occupied France with the gangsters from the milieu (underworld) of Paris and Marseilles soon becoming very rich by supplying rationed goods.[67] The milieu established smuggling networks bringing in rationed goods over the Pyrenées from Spain, and it was soon learned that for the right price, they were also willing to smuggle people out of France like Allied airmen, refugees, Jews, and résistants. Later on in the war, they would smuggle in agents from the SOE.[67] However, the milieu were only interested in making money, and would just as easily betray those who wanted to be smuggled in or out of France if the Germans or Vichy were willing to make a better offer.[67]

On 10 November 1940, a jostle on the Rue de Havre in Paris broke out between some Parisians and German soldiers, which ended with a man raising his fist to a German sergeant, and which led to a man named Jacques Bonsergent, who seems only to have been a witness to the quarrel, being arrested in unclear circumstances.[50] On 11 November 1940, to mark the 22nd anniversary of the French victory of 1918, university students demonstrated in Paris, and were brutally put down by the Paris police.[68] In December 1940, the Organisation civile et militaire (OCM), which consisted of army officers and civil servants, was founded to provide intelligence to the Allies.[48]

On 5 December 1940, Bonsergent was convicted by a German military court of insulting the Wehrmacht. He insisted on taking full responsibility, saying he wanted to show the French what sort of people the Germans were, and he was shot on 23 December 1940.[50] The execution of Bonsergent, a man guilty only of being a witness to an incident that was in itself only very trivial, brought home to many of the French the precise nature of the "New Order in Europe".[69] All over Paris, posters warning that all who challenged the might of the Reich would be shot like Bonsergent were torn down or vandalized, despite the warnings from General von Stülpnagel that damaging the posters was an act of sabotage that would be punished by the death penalty; so many posters were torn down and/or vandalized that Stülpnagal had to post policemen to guard them.[70] Writer Jean Bruller remembered being "transfixed" by reading about Bonsergent's fate and how "people stopped, read, wordlessly exchanged glances. Some of them bared their heads as if in the presence of the dead".[70] On Christmas Day 1940, Parisians woke to find that in the previous night, the posters announcing Bonsergent's execution had been turned into shrines, being in Bruller's words "surrounded by flowers, like on so many tombs. Little flowers of every kind, mounted on pins, had been struck on the posters during the night—real flowers and artificial ones, paper pansies, celluloid roses, small French and British flags".[70] The writer Simone de Beauvoir stated that it was not just Bonsergent that people mourned, but also the end of the illusion "as for the first time these correct people who occupied our country were officially telling us they had executed a Frenchman guilty of not bowing his head to them".[70]

1941: Armed resistance begins

On 31 December 1940, de Gaulle, speaking on the BBC's Radio Londres, asked that the French stay indoors on New Year's Day between 3 and 4:00 pm as a show of passive resistance.[70] The Germans handed out potatoes at that hour in an attempt to bring people away from their radios.[70]

In March 1941, the Calvinist pastor Marc Boegner condemned the Vichy statut des Juifs in a public letter, one of the first times that French antisemitism had been publicly condemned during the occupation.[71] On 5 May 1941, the first SOE agent (Georges Bégué) landed in France to make contact with the resistance groups (Virginia Hall was the first female SOE agent arriving in August 1941). The SOE preferred to recruit French citizens living in Britain or who had fled to the United Kingdom, as they were able to blend in more effectively; British SOE agents were people who had lived in France for a long time and could speak French without an accent. Bégué suggested that the BBC's Radio Londres send personal messages to the Resistance. At 9:15 pm every night, the BBC's French language service broadcast the first four notes of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony (which sounded like the Morse code for V as in victory), followed by cryptic messages, which were codes for the "personal messages" to the resistance.[72] By June 1941, the SOE had two radio stations operating in France.[73] The SOE provided weapons, bombs, false papers, money and radios to the resistance, and the SOE agents were trained in guerrilla warfare, espionage and sabotage. One such SOE operative, American Virginia Hall, established the Heckler network in Lyon.[74]

A major reason for young Frenchmen to become résistants was resentment of collaboration horizontale ("horizontal collaboration"), the euphemistic term for sexual relationships between German men and Frenchwomen.[25] The devaluation of the franc and the German policy of requisitioning food created years of hardship for the French, so taking a German lover was a rational choice for many Frenchwomen. "Horizontal collaboration" was widespread, with 85,000 illegitimate children fathered by Germans born by October 1943.[75] While this number isn't particularly high for the circumstances (although greater than the fewer than 1,000 "Rhineland Bastards" fathered by French soldiers during the Post-WW1 Occupation of Germany), many young Frenchmen disliked the fact that some Frenchwomen seemed to find German men more attractive than them and wanted to strike back.[75]

In Britain, the letter V had been adopted as a symbol of the will to victory, and in the summer of 1941, the V cult crossed the English Channel and the letter V appeared widely in chalk on the pavement, walls, and German military vehicles all over France.[76] V remained one of the main symbols of resistance for the rest of the Occupation, although Ousby has noted that the French had their own "revolutionary, republican, and nationalist traditions" to draw upon for symbols of resistance.[77] Starting in 1941, it was common for crowds to sing La Marseillaise on traditional holidays like May Day, Bastille Day, 6 September (the anniversary of the Battle of the Marne in 1914) and Armistice Day with a special emphasis on the line: "Aux armes, citoyens!" (Citizens to arms!).[78] The underground press created what Ousby called "the rhetoric of resistance to counter the rhetoric of the Reich and Vichy" to inspire people, using sayings from the great figures of French history.[79] The underground newspaper Les Petites Ailes de France quoted Napoleon that "To live defeated is to die every day!"; Liberté quoted Foch that "A nation is beaten only when it has accepted that it is beaten" while Combat quoted Clemenceau: "In war as in peace, those who never give up have the last word".[79] The two most popular figures invoked by the resistance were Clemenceau and Maréchal Foch, who insisted even during the darkest hours of World War I that France would never submit to the Reich and would fight on until victory, which made them inspiring figures to the résistants.[79]

On 22 June 1941, Germany launched Operation Barbarossa and invaded the Soviet Union.[59] Well prepared for the resistance through the clandestinity in which they were forced during the Daladier government, the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) began fighting German occupation forces in May 1941, i.e. before the Comintern appeal that followed the German attack to the Soviet Union.[80] Nevertheless, communists had a more prominent role in the resistance only after June 1941.[59] As the Communists were used to operating in secret, were tightly disciplined, and had a number of veterans of the Spanish Civil War, they played a disproportionate role in the Resistance.[59] The Communist resistance group was the FTP (Francs-Tireurs et Partisans Français-French Snipers and Partisans) headed by Charles Tillon.[81] Tillon later wrote that between June–December 1941 the RAF carried out 60 bombing attacks and 65 strafing attacks in France, which killed a number of French people, while the FTP, during the same period, set off 41 bombs, derailed 8 trains and carried out 107 acts of sabotage, which killed no French people.[82] In the summer of 1941, a brochure appeared in France entitled Manuel du Légionnaire, which contained detailed notes on how to fire guns, manufacture bombs, sabotage factories, carry out assassinations, and perform other skills useful to the resistance.[83] The brochure was disguised as informational material for fascistic Frenchmen who had volunteered for the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism on the Eastern Front;[83] it took the occupation authorities some time to realize that the manual was a Communist publication meant to train the FTP for actions against them.[83]

On 21 August 1941, a French Communist, Pierre Georges, assassinated the German naval officer Anton Moser in the Paris Metro, the first time the resistance had killed a German.[59] The German Military Governor General Otto von Stülpnagel had three people shot in retaliation, none of whom were connected to his killing.[45] General Stülpnagel announced on 22 August 1941 that for every German killed, he would execute at least ten innocent French people, and that all Frenchmen in German custody were now hostages.[59] On 30 September 1941, Stülpnagel issued the "Code of Hostages", ordering all district chiefs to draw up lists of hostages to be executed in the event of further "incidents", with an emphasis on French Jews and people known for Communist or Gaullist sympathies.[84] On 20 October 1941, Oberstleutnant Karl Friedrich Hotz, the Feldkommandant of Nantes, was assassinated on the streets of Nantes; the military lawyer Dr. Hans Gottfried Reimers was assassinated in Bordeaux on 21 October.[81] In retaliation the Wehrmacht shot 50 unconnected French people in Nantes, and announced that if the assassin did not turn himself in by midnight of 23 October, another 50 would be shot.[81] The assassin did not turn himself in, and so another 50 hostages were shot, among them Léon Jost, a former Socialist deputy and one-legged veteran of the First World War, who was serving a three-year prison sentence for helping Jews to escape into Spain.[85] The same day, the Feldkommandant of Bordeaux had 50 French hostages shot in that city in retaliation for Reimers's assassination.[81] The executions in Nantes and Bordeaux started a debate about the morality of assassination that lasted until the end of the occupation; some French argued that since the Germans were willing to shoot so many innocent people in reprisal for killing only one German that it was not worth it, while others contended that to cease assassinations would prove that the Germans could brutally push the French around in their own country.[81] General de Gaulle went on the BBC's French language service on 23 October to ask that PCF to call in their assassins, saying that killing one German would not change the outcome of the war and that too many innocent people were being shot by Germans in reprisals. As the PCF did not recognize de Gaulle's authority, the Communist assassins continued their work under the slogan "an eye for an eye", and so the Germans continued to execute between 50 and 100 French hostages for every one of their number assassinated.[81]

As more resistance groups started to appear, it was agreed that more could be achieved by working together than apart. The chief promoter of unification was a former préfet of Chartres, Jean Moulin.[86] After identifying the three largest resistance groups in the south of France that he wanted to see co-operate, Moulin went to Britain to seek support.[86] Moulin made a secret trip, visiting Lisbon on 12 September 1941, from whence he traveled to London to meet General de Gaulle on 25 October 1941.[86] De Gaulle named Moulin his representative in France, and ordered him to return and unify all Resistance groups and have them recognize the authority of de Gaulle's Free French National Committee in London, which few resistance groups did at the time.[86] To lend further support, in October 1941 de Gaulle founded the BCRA (Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action – Central Office for Intelligence and Action) under André Dewavrin, who used the codename "Colonel Passy" to provide support for the Resistance.[48] Though the BCRA was based in an office in Duke Street in London, its relations with the SOE were often strained, as de Gaulle made no secret of his dislike of British support for the resistance groups, which he saw as British meddling in France's domestic affairs.[87] Tensions between Gaullist and non-Gaullist resistance groups led to the SOE dividing its F section in two, with the RF section providing support for Gaullist groups and the F section dealing with the non-Gaullist groups.[47]

British SOE agents parachuted into France to help organize the resistance often complained about what they considered the carelessness of the French groups when it came to security.[88] A favorite tactic of the Gestapo and the Abwehr was to capture a résistant, "turn" him or her to their side, and then send the double agent to infiltrate the resistance network.[89] Numerous resistance groups were destroyed by such double agents, and the SOE often charged that the poor security arrangements of the French resistance groups left them open to being destroyed by one double agent.[90] For example, the Interallié group was destroyed when Carré was captured and turned by Abwehr Captain Hugo Bleicher on 17 November 1941, as she betrayed everyone.[47] The same month, Colonel Alfred Heurtaux of the OCM was betrayed by an informer and arrested by the Gestapo. In November 1941, Frenay recruited Jacques Renouvin, whom he called an "experienced brawler", to lead the new Groupes Francs paramilitary arm of the Combat resistance group.[91] Renouvin taught his men military tactics at a secret boot camp in the countryside in the south of France and led the Groupes Francs in a series of attacks on collaborators in Lyon and Marseilles.[91] Frenay and Renouvin wanted to "blind" and "deafen" the French police by assassinating informers who were the "eyes" and "ears" of the police.[91] Renouvin, who was a known "tough guy" and experienced killer, personally accompanied résistants on their first assassinations to provide encouragement and advice.[91] If the would-be assassin was unable to take a life, Renouvin would assassinate the informer himself, then berate the would-be assassin for being a "sissy" who was not tough enough for the hard, dangerous work of the Resistance.[91]

On 7 December 1941, the Nacht und Nebel decree was signed by Hitler, allowing the German forces to "disappear" anyone engaged in resistance in Europe into the "night and fog".[92] During the war, about 200,000 French citizens were deported to Germany under the Nacht und Nebel decree, about 75,000 for being résistants, half of whom did not survive.[92] After Germany declared war on the United States on 11 December 1941, the SOE was joined by the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) to provide support for the resistance.[47] In December 1941, after the industrialist Jacques Arthuys, the chief of the OCM, was arrested by the Gestapo, who later executed him, leadership of was assumed by Colonel Alfred Touny of the Deuxième Bureau, which continued to provide intelligence to the Free French leaders in exile in Britain.[48] Under the leadership of Touny, the OCM became one of the Allies' best sources of intelligence in France.[48]

1942: The struggle intensifies

On the night of 2 January 1942, Moulin parachuted into France from a British plane with orders from de Gaulle to unify the Resistance and to have all of the resistance accept his authority.[86] On 27 March 1942, the first French Jews were rounded up by the French authorities, sent to the camp at Drancy, then on to Auschwitz to be killed.[93] In April 1942, the PCF created an armed wing of its Main d'Oeuvre Immigrée ("Migrant Workforce") representing immigrants called the FTP-MOI under the leadership of Boris Holban, who came from the Bessarabia region, which belonged alternately to either Russia or Romania.[46] On 1 May 1942, May Day, which Vichy France had tried to turn into a Catholic holiday celebrating St. Philip, Premier Pierre Laval was forced to break off his speech when the crowd began to chant "Mort à Laval" (death to Laval).[77]

As millions of Frenchmen serving in the French Army had been taken prisoner by the Germans in 1940, there was a shortage of men in France during the Occupation, which explains why Frenchwomen played so a prominent role in the Resistance, with the résistante Germaine Tillion later writing: "It was women who kick-started the Resistance."[75] In May 1942, speaking before a military court in Lyon, the résistante Marguerite Gonnet, when asked about why she had taken up arms against the Reich, replied: "Quite simply, colonel, because the men had dropped them."[75] In 1942, the Royal Air Force (RAF) attempted to bomb the Schneider-Creusot works at Lyon, which was one of France's largest arms factories.[94] The RAF missed the factory and instead killed around 1,000 French civilians.[94] Two Frenchmen serving in the SOE, Raymond Basset (codename Mary) and André Jarrot (codename Goujean), were parachuted in and were able to repeatedly sabotage the local power grid to sharply lower production at the Schneider-Creusot works.[94] Freney, who had emerged as a leading résistant, recruited the engineer Henri Garnier living in Toulouse to teach French workers at factories producing weapons for the Wehrmacht how best to drastically shorten the lifespan of the Wehrmacht's weapons, usually by making deviations of a few millimetres, which increased strain on the weapons; such acts of quiet sabotage were almost impossible to detect, which meant no French people would be shot in reprisal.[94]

To maintain contact with Britain, Resistance leaders crossed the English Channel at night on a boat, made their way via Spain and Portugal, or took a "spy taxi", as the British Lysander aircraft were known in France, which landed on secret airfields at night.[73] More commonly, contact with Britain was maintained via radio.[73] The Germans had powerful radio detection stations based in Paris, Brittany, Augsburg, and Nuremberg that could trace an unauthorized radio broadcast to within 16 kilometres (10 miles) of its location.[73] Afterwards, the Germans would send a van with a radio detection equipment to find the radio operator,[95] so radio operators in the Resistance were advised not to broadcast from the same location for long.[96] To maintain secrecy, radio operators encrypted their messages using polyalphabetic ciphers.[96] Finally, radio operators had a security key to begin their messages with; if captured and forced to radio Britain under duress, the radio operator would not use the key, which tipped London off that they had been captured.[96]

On 29 May 1942 it was announced that all Jews living in the occupied zone had to wear a yellow star of David with the words Juif or Juive at all times by 7 June 1942.[97] Ousby described the purpose of the yellow star "not just to identify but also to humiliate, and it worked".[98] On 14 June 1942, a 12-year-old Jewish boy committed suicide in Paris as his classmates were shunning the boy with the yellow star.[98] As a form of quiet protest, many Jewish veterans started to wear their medals alongside the yellow star, which led the Germans to ban the practice as "inappropriate", as it increased sympathy for men who fought and suffered for France.[99] At times, ordinary people would show sympathy for Jews; as a Scot married to a Frenchman, Janet Teissier du Cros wrote in her diary about a Jewish woman wearing her yellow star of David going shopping:

She came humbly up and stood hesitating on the edge of the pavement. Jews were not allowed to stand in queues. What they were supposed to do I never discovered. But the moment the people in the queue saw her they signaled to her to join us. Secretly and rapidly, as in the game of hunt-the-slipper, she was passed up till she stood at the head of the queue. I am glad to say that not one voice was raised in protest, the policeman standing near turned his head away, and that she got her cabbage before any of us.[97]

By 1942, the Paris Kommandantur was receiving an average of 1,500 poison pen letters from corbeaux wishing to settle scores, which kept the occupation authorities informed about what was happening in France.[62] One of these corbeaux, a Frenchwoman displaying the typically self-interested motives of her ilk, read:

Since you are taking care of the Jews, and if your campaign is not just a vain word, then have a look at the kind of life led by the girl M.A, formerly a dancer, now living at 41 Boulevard de Strasbourg, not wearing a star. This creature, for whom being Jewish is not enough, debauches the husbands of proper Frenchwomen, and you may well have an idea what she is living off. Defend women against Jewishness—that will be your best publicity, and you will return a French husband to his wife.[63]

In the spring of 1942, a committee consisting of SS Hauptsturmführer Theodor Dannecker, the Commissioner for Jewish Affairs Louis Darquier de Pellepoix, and general secretary of the police René Bousquet began planning a grande rafle (great round-up) of Jews to deport to the death camps.[100] On the morning of 16 July 1942, the grande rafle began with 9,000 French policemen rounding up the Jews of Paris, leading to some 12,762 Jewish men, women and children being arrested and brought to the Val d'Hiv sports stadium, from where they were sent to the Drancy camp and finally Auschwitz.[101] The grand rafle was a Franco-German operation; the overwhelming majority of those who arrested the Jews were French policemen.[101] Some 100 Jews warned by friends in the police killed themselves, while 24 Jews were killed resisting arrest.[101] One Jewish Frenchwoman, Madame Rado, who was arrested with her four children, noted about the watching bystanders: "Their expressions were empty, apparently indifferent."[102] When taken with the other Jews to the Place Voltaire, one woman was heard to shout "Well done! Well done!" while the man standing to her warned her "After them, it'll be us. Poor people!".[102] Rado survived Auschwitz, but her four children were killed in the gas chambers.[102]

Cardinal Pierre-Marie Gerlier of Lyon, a staunch antisemite who had supported Vichy's efforts to solve the "Jewish question" in France, opposed the rafles of Jews, arguing in a sermon that the "final solution" was taking things too far; he felt it better to convert Jews to Roman Catholicism.[102] Archbishop Jules-Géraud Saliège of Toulouse, in a pastoral letter of 23 August 1942, declared: "You cannot do whatever you wish against these men, against these women, against these fathers and mothers. They are part of mankind. They are our brothers."[71] Pastor Marc Boegner, president of the National Protestant Federation, denounced the rafles in a sermon in September 1942, asking Calvinists to hide Jews.[71] A number of Catholic and Calvinist schools and organizations such as the Jesuit Pierre Chaillet's l'Amitié Chrétienne took in Jewish children and passed them off as Christian.[71] Many Protestant families, with memories of their own persecution, had already begun to hide Jews, and after the summer of 1942, the Catholic Church, which until then had been broadly supportive of Vichy's antisemitic laws, began to condemn antisemitism, and organized efforts to hide Jews.[71] The official story was that the Jews were being "resettled in the East", being moved to a "Jewish homeland" somewhere in Eastern Europe.[102] As the year continued, the fact that no one knew precisely where this Jewish homeland was, together with the fact that those sent to be "resettled" were never heard from again, led more and more people to suspect that rumors of the Jews being exterminated were true.[102]

Ousby argued that, given the widespread belief that the Jews in France were mostly illegal immigrants from Eastern Europe who ought to be sent back to where they came from, it was remarkable that so many ordinary people were prepared to attempt to save them.[71] Perhaps the most remarkable example was the effort of the Calvinist couple André and Magda Trocmé, who brought together an entire commune, Le Chambon-sur-Lignon, to save between 800 and 1,000 Jews.[103] The Jews in France, whether they were Israélites or immigrant Juifs, had begun the occupation discouraged and isolated, cut off and forced to become "absent from the places they lived in. Now, as the threat of absence become brutally literal, their choices were more sharply defined, more urgent even than for other people in France."[71] As an example of the "differing fates" open to French Jews from 1942 onward, Ousby used the three-part dedication to the memoir Jacques Adler wrote in 1985: the first part dedicated to his father, who was killed at Auschwitz in 1942; the second to the French family who sheltered his mother and sister, who survived the Occupation; and the third to the members of the Jewish resistance group Adler joined later in 1942.[71]

As in World War I and the Franco-Prussian War, the Germans argued that those engaging in resistance were "bandits" and "terrorists", maintaining that all Francs-tireurs were engaging in illegal warfare and therefore had no rights.[96] On 5 August 1942, three Romanians belonging to the FTP-MOI tossed grenades into a group of Luftwaffe men watching a football game at the Jean-Bouin Stadium in Paris, killing eight and wounding 13.[104] The Germans claimed three were killed and 42 wounded; this let them execute more hostages, as Field Marshal Hugo Sperrle demanded three hostages be shot for every dead German and two for each of the wounded.[105] The Germans did not have that many hostages in custody and settled for executing 88 people on 11 August 1942.[105] The majority of those shot were communists or relatives of communists, along with the father and father-in-law of Pierre Georges and the brother of the communist leader Maurice Thorez.[105] A number were Belgian, Dutch, and Hungarian immigrants to France; all went before the firing squads singing the French national anthem or shouting Vive la France!, a testament to how even the communists by 1942 saw themselves as fighting for France as much as for world revolution.[105]

Torture of captured résistants was routine.[96] Methods of torture included beatings, shackling, being suspended from the ceiling, being burned with a blowtorch, allowing dogs to attack the prisoner, being lashed with ox-hide whips, being hit with a hammer, or having heads placed in a vice, and the baignoire, whereby the victim was forced into a tub of freezing water and held nearly to the point of drowning, a process repeated for hours.[106] A common threat to a captured résistant was to have a loved one arrested or a female relative or lover sent to the Wehrmacht field brothels.[106] The vast majority of those tortured talked.[106] At least 40,000 French died in such prisons.[106] The only way to avoid torture was to be "turned", with the Germans having a particular interest in turning radio operators who could compromise an entire Resistance network.[96] Captured résistants were held in filthy, overcrowded prisons full of lice and fleas and fed substandard food or held in solitary confinement.[96]

On 1 December 1942, a new resistance group, the ORA, Organisation de résistance de l'armée (Army Resistance Organization), was founded.[48] The ORA was headed by General Aubert Frère and recognized General Henri Giraud as France's leader.[48] For a time in 1942–1943, there were two rival leaders of the Free French movement in exile: General Giraud, backed by the United States, and General de Gaulle, backed by Great Britain.[48] For these reasons, the ORA had bad relations with the Gaullist resistance while being favored by the OSS, as the Americans did not want de Gaulle as France's postwar leader.[48] By the end of 1942, there were 278 sabotage actions in France vs. 168 Anglo-American bombings in France.[82]

1943: A mass movement emerges

On 26 January 1943, Moulin persuaded the three main resistance groups in the south of France—Franc-Tireur, Liberation and Combat—to unite as the MUR (Mouvements Unis de Résistance or United Resistance Movement), whose armed wing was the AS (Armée Secrète or Secret Army).[107] The MUR recognised General de Gaulle as the leader of France and selected General Charles Delestraint (codename Vidal) as the commander of the AS.[107] Moulin followed this success by contracting resistance groups in the north such as Ceux de la Résistance, Ceux de la Libération, Comité de Coordination de Zone Nord, and Libération Nord to ask to join.[108]

Reflecting the growth of the Resistance, on 30 January 1943, the Milice was created to hunt down the résistants, although initially that was only one of the Milice's tasks; it was first presented as an organisation to crack down on the black market.[109] The Milice, commanded by Joseph Darnand, was a mixture of fascists, gangsters, and adventurers with a "sprinkling of the respectable bourgeoisie and even the disaffected aristocracy" committed to fight to the death against the "Jews, Communists, Freemasons and Gaullists"; the oath of those who joined required to them to commit to work for the destruction in France of the "Jewish leprosy", the Gaullists and the Communists.[109] The Milice had 29,000 members, of whom 1,000 belonged to the elite Francs-Gardes and wore a uniform of khaki shirts, black berets, black ties, blue trousers and blue jackets. Their symbol was the white gamma, the zodiacal sign of the Ram, symbolising renewal and power.[110] The Germans did not want any of the French to be armed, even collaborators, and initially refused to provide the Milice with weapons.[111]

On 16 February 1943, the Service du Travail Obligatoire (STO) organisation was created, requiring able-bodied Frenchmen to work in Germany.[75] In the Reich, with so many men called up for service with the Wehrmacht and the Nazi régime reluctant to have German women work in factories (Hitler believed working damaged a woman's womb), the German state brought foreign workers to Germany to replace the men serving in the Wehrmacht. At the Dora works near the Buchenwald concentration camp, about 10,000 slave workers, mostly French and Russian, built V2 rockets in a vast subterranean factory; they lived in quarters meant to house only 2,500, were allowed to sleep only four and half hours every night, and were regularly brutalised by the guards.[112] The chief pleasure of the slaves was urinating on the machinery when the guards were not looking.[112] The underground press gave much coverage to the conditions at the Dora works, pointing out those Frenchmen who went to work in Germany were not paid the generous wages promised by the Organisation Todt and instead were turned into slaves, all of which the underground papers used as reasons for why the French should not go to work in Germany.[112] Under the law of 16 February 1943, all able-bodied Frenchmen aged 20–22 who were not miners, farmers or university students had to report to the STO to do two years labour in Germany.[113]

As the occupation went on, service with the STO was widened, with farmers and university students losing their exempt status until 1944, when all fit men aged 18–60 and women aged 18–45 were being called up for service with the STO.[113] Men over 45 and women serving in the STO were guaranteed not to go to Germany and many were put to work building the Atlantic Wall for the Organisation Todt, but had no way of knowing where they would go.[113] The so-called réfractaires attempted to avoid being called up and often went into hiding rather work for the Reich.[114] At least 40,000 Frenchmen (80% of the resistance were people under thirty) fled to the countryside, becoming the core of the maquis guerrillas.[75] They rejected the term réfractaire with its connotations of laziness and called themselves the maquis, which originated as Corsican Italian slang for bandits, whose root word was macchia, the term for the scrubland and forests of Corsica.[115] Those who lived in the macchia of Corsica were usually bandits, and those men fleeing to the countryside chose the term maquis as a more romantic and defiant term than réfractaire.[115] By June 1943, the term maquis, which had been a little-known word borrowed from the Corsican dialect of Italian at the beginning of 1943, became known all over France.[115] It was only in 1943 that guerilla warfare emerged in France as opposed to the more sporadic attacks against the Germans that had continued since the summer of 1941, and the Resistance changed from an urban movement to a rural movement, most active in central and southern France.[116]

Fritz Sauckel, the General Plenipotentiary for Labour Deployment and the man in charge of bringing slaves to German factories, demanded the flight of young men to the countryside be stopped and called the maquis "terrorists", "bandits" and "criminals".[117] One of every two French people called to serve in the STO failed to do so.[118] Sauckel had been ordered by Hitler in February 1943 to produce half a million workers from France for German industry by March, and it was he who had pressured Laval to create the STO with the law of 16 February 1943.[113] Sauckel had joined the NSDAP in 1923, making him an Alter Kämpfer (Old Fighter), and like many other Alte Kämpfer (who tended to be the most extreme Nazis), Sauckel was a hard man. Despite warnings from Laval, Sauckel took the view that he was ordered by Albert Speer to produce a quota of slaves for German industry, that the men joining the maquis were sabotaging German industry by fleeing to the countryside, and the solution was simply to kill them all.[119] Sauckel believed that once the maquis were wiped out, Frenchmen would obediently report to the STO and go to work in Germany. When Laval was presented with Sauckel's latest demand for French labor for German industry, he remarked: "Have you been sent by de Gaulle?".[120] Laval argued the réfractaires were not political opponents and should not be treated as such, arguing that an amnesty and a promise that the réfractaires would not be sent as slaves to Germany would nip the budding maquis movement.[119]

As Laval predicted, the hardline policies that Sauckel advocated turned the basically apolitical maquis political, driving them straight into the resistance as the maquisards turned to the established resistance groups to ask for arms and training.[119] Sauckel decided that if Frenchmen would not report to the STO, he would have the Todt organisation use the shanghaillage (shanghaiing), storming into cinemas to arrest the patrons or raiding villages in search of bodies to turn into slaves to meet the quotas.[120] Otto Abetz, the Francophile German ambassador to Vichy, had warned that Sauckel was driving the maquis into the resistance with his hardline policies and joked to Sauckel that the maquis should put up a statue of him with the inscription "To our number one recruitment agent".[120] The French called Sauckel "the slave trader".[118] Furthermore, as Laval warned, the scale of the problem was beyond Vichy's means to solve. The prefets of the departments of the Lozère, the Hérault, the Aude, the Pyrénées-Orientales and Avéron had been given a list of 853 réfractaires to arrest, and managed during the next four months to arrest only 1 réfractaire.[119]

After the Battle of Stalingrad, which ended with the destruction of the entire German 6th Army in February 1943, many had started to doubt the inevitability of an Axis victory, and most French gendarmes were not willing to hunt the down the maquis, knowing that they might be tried for their actions if the Allies won.[121] Only the men of the Groupe mobile de réserve paramilitary police were considered reliable, but the force was too small to hunt down thousands of men.[121] As the Germans preferred to subcontract the work of ruling France to the French while retaining ultimate control, it was the Milice that was given the task of destroying the maquis.[122] The Milice was in Ousby's words "Vichy's only instrument for fighting the Maquis. Entering the popular vocabulary at more or less the same time, the words maquis and milice together defined the new realities: the one a little-known word for the back country of Corsica, which became a synonym for militant resistance; the other a familiar word meaning simply "militia", which became a synonym for militant repression. The Maquis and the Milice were enemies thrown up by the final chaos of the Occupation, in a sense twins symbiotically linked in a final hunt."[122]

The established Resistance groups soon made contact with the maquis, providing them with paramilitary training.[49] Frenay remembered:

We established contact with them through our departmental and regional chiefs. Usually these little maquis voluntarily followed our instructions, in return for which they expected food, arms and ammunition ... It seemed to me that these groups, which were now in hiding all over the French mountain country, might well be transformed into an awesome combat weapon. The maquisards were all young, all volunteers, all itching for action ... It was up to us to organize them and give them a sense of their role in the struggle.[107]

The terrain of central and southern France with its forests, mountains, and shrubland were ideal for hiding, and as the authorities were not prepared to commit thousands of men to hunt the maquis down, it was possible to evade capture.[123] The Germans could not spare thousands of men to hunt the maquis down, and instead sent spotter planes to find them. The maquis were careful about concealing fires and could usually avoid aerial detection.[123] The only other way of breaking up the maquis bands was to send in a spy, which was highly dangerous work as the maquisards would execute infiltrators.[123] Joining the men fleeing the service with the STO were others targeted by the Reich, such as Jews, Spanish Republican refugees, and Allied airmen shot down over France.[124] One maquis band in the Cévennes region consisted of German communists who had fought in the Spanish Civil War and fled to France in 1939.[46] Unlike the urban resistance groups that emerged in 1940–42, who took political names such as Combat, Liberté or Libération, the maquis bands chose apolitical names, such as the names of animals (Ours, Loup, Tigre, Lion, Puma, Rhinocéros and Eléphant) or people (Maquis Bernard, the Maquis Socrate, the Maquis Henri Bourgogne, or one band whose leader was a doctor, hence the name Maquis le Doc).[125] The maquis bands that emerged in the countryside soon formed a subculture with its own slang, dress and rules.[126] The most important maquis rule was the so-called "24-hour rule", under which a captured maquisard had to hold out under torture for 24 hours to give time for his comrades to escape.[127] An underground pamphlet written for young men considering joining the maquis advised:

Men who come to the Maquis to fight live badly, in precarious fashion, with food hard to find. They will be absolutely cut off from their families for the duration; the enemy does not apply the rules of war to them; they cannot be assured any pay; every effort will be made to help their families, but it is impossible to give any guarantee in this manner; all correspondence is forbidden.

Bring two shirts, two pairs of underpants, two pairs of woollen socks; a light sweater, a scarf, a heavy sweater, a woollen blanket, an extra pair of shoes, shoelaces, needles, thread, buttons, safety pins, soap, a canteen, a knife and fork, a torch, a compass, a weapon if possible, and also a sleeping bag if possible. Wear a warm suit, a beret, a raincoat, a good pair of hobnailed boots.[128]

Another pamphlet written for the maquis advised:

A maquisard should stay only where he can see without being seen. He should never live, eat, sleep except surrounded by look-outs. It should never be possible to take him by surprise.

A maquisard should be mobile. When a census or enlistment [for the STO] brings new elements he has no means of knowing into his group, he should get out. When one of the members deserts, he should get out immediately. The man could be a traitor.

Réfractaires, it is not your duty to die uselessly.[126]

One maquisard recalled his first night out in the wildness:

Darkness falls in the forest. On one path, some distance from the our camp, two boys stand guard over the safety of their comrades. One has a pistol, the other a service rifle, with a few spare cartridges in a box. Their watch lasts for two hours. How amazing those hours on duty in the forest at night are! Noises come from everywhere and the pale light of the moon gives everything a queer aspect. The boy looks at a small tree and think he sees it move. A lorry passes on a distant road; could it be the Germans? ... Are they going to stop? [128]

Ousby stated that the "breathless prose" in which this maqusiard remembered his first night out in the forest was typical of the maqusiards whose main traits were their innocence and naivety; many seemed not to understand just precisely who they were taking on or what they were getting themselves into by fleeing to the countryside.[128]

Unlike the andartes, who were resisting Axis rule in Greece and preferred a democratic decision-making progress, the maquis bands tended to be dominated by a charismatic leader, usually an older man who was not a réfractaire; a chef who was commonly a community leader; somebody who before the war had been a junior political or military leader under the Third Republic; or somebody who had been targeted by the Reich for political or racial reasons.[129] Regardless whether they had served in the military, the maquis chefs soon started calling themselves capitaines or colonels.[125] The aspect of life in the maquis best remembered by veterans was their youthful idealism, with most of the maquisards remembering how innocent they were, seeing their escape into the countryside as a grand romantic adventure, by which, as Ousby observed, "they were nervously confronting new dangers they barely understood; they were proudly learning new techniques of survival and battle. These essential features stand out in accounts by maquisards even after innocence had quickly given way to experience, which made them regard danger and discipline as commonplace."[128] The innocence of the maquisards was reflected in the choice of names they took, which were usually whimsical and boyish names, unlike those used by the résistants in the older groups, which were always serious.[125] The maquis had little in the way of uniforms, with the men wearing civilian clothing with a beret being the only common symbol of the maquis, as a beret was sufficiently common in France not to be conspicuous, but uncommon enough to be the symbol of a maquisard.[130] To support themselves, the maquis took to theft, with bank robbery and stealing from the Chantiers de Jeunesse (the Vichy youth movement) being especially favored means of obtaining money and supplies.[131] Albert Spencer, a Canadian airman shot down over France while on a mission to drop leaflets over France who joined the maquis, discovered the distinctive slang of the maquisards, learning that the leaflets he had been dropping over France were torche-culs (ass-wipes) in maquis slang.[132]

As the maquis grew, the Milice was deployed to the countryside to hunt them down and the first milicien was killed in April 1943.[110] As neither the maquis or the milice had many guns, the casualties were low at first, and by October 1943 the Milice had suffered only ten dead.[111] The SOE made contact with the maquis bands, but until early 1944 the SOE were unable to convince Whitehall that supplying the Resistance should be a priority.[133]

Until 1944, there were only 23 Halifax bombers committed to supplying Resistance groups for all of Europe, and many in the SOE preferred resistance groups in Yugoslavia, Italy and Greece be armed rather than French ones.[134] On 16 April 1943, the SOE agent Odette Sansom was arrested with her fellow SOE agent and lover Peter Churchill by the Abwehr Captain Hugo Bleicher.[106] After her arrest, Sansom was tortured for several months, which she recounted in the 1949 book Odette: The Story of a British Agent.[106] Sansom recalled:

In those places the only thing one could try to keep was a certain dignity. There was nothing else. And one could have a little dignity and try to prove that one had a little spirit and, I suppose, that kept one going. When everything else was too difficult, too bad, then one was inspired by so many things-people; perhaps a phrase one would remember that one had heard a long time before, or even a piece of poetry or a piece of music.[106]

On 26 May 1943, in Paris, Moulin chaired a secret meeting attended by representatives of the main resistance groups to form the CNR (Conseil National de la Résistance-National Council of the Resistance).[108] With the National Council of the Resistance, resistance activities started to become more coordinated. In June 1943, a sabotage campaign began against the French rail system. Between June 1943 – May 1944, the Resistance damaged 1,822 trains, destroyed 200 passenger cars, damaged about 1,500 passenger cars, destroyed about 2,500 freight cars and damaged about 8,000 freight cars.[135]

The résistant René Hardy had been seduced by the French Gestapo agent Lydie Bastien whose true loyalty was to her German lover, Gestapo officer Harry Stengritt. Hardy was arrested on 7 June 1943 when he walked into a trap laid by Bastien.[136] After his arrest, Hardy was turned by the Gestapo as Bastien tearfully told him that she and her parents would all be sent to a concentration camp if he did not work for the Gestapo. Hardy was unaware that Bastien really loathed him and was only sleeping with him under Stengritt's orders.[136] On 9 June 1943, General Delestraint was arrested by the Gestapo following a tip-off provided by the double agent Hardy and was sent to the Dachau concentration camp.[108] On 21 June 1943, Moulin called a secret meeting in Caluire-et-Cuire suburb of Lyon to discuss the crisis and try to find the traitor who betrayed Delestraint.[108] At the meeting, Moulin and the rest were arrested by SS Hauptsturmführer Klaus Barbie, the "Butcher of Lyon".[108] Barbie tortured Moulin, who never talked.[108] Moulin was beaten into a coma and died on 8 July 1943 as a result of brain damage.[108] Moulin was not the only Resistance leader arrested in June 1943. That same month, General Aubert Frère, the leader of the ORA, was arrested and later executed.[135]

In the summer of 1943, leadership of the FTP-MOI was assumed by an Armenian immigrant Missak Manouchian, who become so famous for organizing assassinations that the FTP-MOI came to be known to the French people as the Groupe Manouchian.[47] In July 1943, the Royal Air Force attempted to bomb the Peugeot works at Sochaux, which manufactured tank turrets and engine parts for the Wehrmacht.[94] The RAF instead hit the neighborhood next to the factory, killing hundreds of French civilians.[94] To avoid a repeat, the SOE agent Harry Rée contacted industrialist Rudolphe Peugeot to see if he was willing to sabotage his own factory.[94] To prove that he was working for London, Rée informed Peugeot that the BBC's French language "personal messages" service would broadcast a message containing lines from a poem that Rée had quoted that night; after hearing the poem in the broadcast, Peugeot agreed to co-operate.[94] Peugeot gave Rée the plans for the factory and suggested the best places to sabotage his factory without injuring anyone by selectively placing plastic explosives.[94] The Peugeot works were largely knocked out in a bombing organised by Rée on 5 November 1943 and output never recovered.[94] The Michelin family were approached with the same offer and declined.[94] The RAF bombed the Michelin factory at Clermont-Ferrand—France's largest tyre factory and a major source of tyres for the Wehrmacht—into the ground.[94]

Despite the blow inflicted by Barbie by arresting Moulin, by 1 October 1943 the AS had grown to 241,350 members, though most were still unarmed.[107] For the most part, the AS refrained from armed operations as it was no match for the Wehrmacht.[107] Instead the AS forced on preparing for Jour J, when the Allies landed in France, after which the AS would begin action.[107] In the meantime, the AS focused on training its members and conducting intelligence-gathering operations for the Allies.[107] In October 1943, Joseph Darnand, the chief of the Milice who had long been frustrated at the unwillingness of the Germans to arm his force, finally won the trust of the Reich by taking a personal oath of loyalty to Hitler and being commissioned as a Waffen-SS officer together with 11 other Milice leaders.[111] With that, the Germans started to arm the Milice, which turned its guns on the Resistance.[111] The weapons the German provided the Milice with were mostly British weapons captured at Dunkirk in 1940, and as the maquis received many weapons from the SOE, it was often the case that in the clashes between Milice and the Maquis, Frenchmen fought Frenchmen with British guns and ammunition.[111]

In October 1943, following a meeting between General Giraud and General de Gaulle in Algiers, orders went out for the AS and ORA to cooperate in operations against the Germans.[137] One of the most famous Resistance actions took place on 11 November 1943 in the town of Oyonnax in the Jura Mountains, where about 300 maqusiards led by Henri Romans-Petit arrived to celebrate the 25th anniversary of France's victory over Germany in 1918, wearing improvised uniforms.[138] There were no Germans in Oyonnax that day and the gendarmes made no effort to oppose the Resistance, who marched through the streets to lay a wreath shaped like the Cross of Lorraine at a local war memorial bearing the message "Les vainqueurs de demain à ceux de 14–18" ("From tomorrow's victors to those of 14–18").[139] Afterwards, the people of Oyonnax joined the maquisards in singing the French national anthem as they marched, an incident given much play on the BBC's French language service about how one town had been "liberated" for a day.[120] The next month, the SS arrested 130 Oyonnax residents and sent them to the concentration camps, shot the town's doctor, and tortured and deported two other people, including the gendarme captain who failed to resist the maquis on 11 November.[140] On 29 December 1943, the AS and the Communist FTP agreed to cooperate; their actions were controlled by the COMAC (Comité Militaire d'Action-Committee for Military Action), which in turn took its orders from the CNR.[137] The Communists agreed to unity largely in the belief that they would obtain more supplies from Britain, and in practice the FTP continued to work independently.[137] The SOE provided training for the Resistance; however, as the SOE agent Roger Miller noted after visiting a resistance workshop making bombs in late 1943:

If the instructors from the training schools in England could have seen those Frenchmen making up charges the cellar would looked to them like Dante's Inferno. Every conceivable school "don't" was being done.[82]

1944: The height of the Resistance

By the beginning of 1944, the BCRA was providing the Allies with two intelligence assessments per day based on information provided by the Resistance.[48] One of the BCRA's most effective networks was headed by Colonel Rémy who headed the Confrérie de Notre Dame (Brotherhood of Notre Dame) which provided photographs and maps of German forces in Normandy, most notably details of the Atlantic Wall.[48] In January 1944, following extensive lobbying by the SOE, Churchill was persuaded to increase by 35 the number of planes available to drop in supplies for the maquis. By February 1944, supply drops were up by 173%.[141] The same month, the OSS agreed to supply the maquis with arms.[142] Despite the perennial shortage of arms, by the early 1944 there were parts of rural areas in the south of France that were more under the control of the maquis than the authorities.[143] By January 1944, a civil war had broken out with the Milice and maquis assassinating alternatively leaders of the Third Republic or collaborators that was to become increasingly savage as 1944 went on.[144] The Milice were loathed by the resistance as Frenchmen serving the occupation and unlike the Wehrmacht and the SS, were not armed with heavy weapons nor were especially well trained, making them an enemy who could be engaged on more or less equal terms, becoming the preferred opponent of the Maquis.[145] The men of the Wehrmacht were German conscripts whereas the Milice were French volunteers, thus explains why the résistants hated the Milice so much.[145] On 10 January 1944, the Milice "avenged" their losses at the hands of the maquis by killing Victor Basch and his wife outside Lyon.[144] The 80 year-old Basch was a French Jew, a former president of the League for the Rights of Men and had been a prominent dreyfusard during the Dreyfus affair, marking him out as an enemy of the "New Order in Europe" by his very existence, though the elderly pacifist Basch was not actually involved in the resistance.[144] The milicien who killed Basch was an anti-Semitic fanatic named Joseph Lécussan who always kept a Star of David made of human skin taken from a Jew he killed earlier in his pocket, making him typical of the Milice by this time.[144]

As the Resistance had not been informed of the details of Operation Overlord, many Resistance leaders had developed their own plans to have the maquis seize large parts of central and southern France, which would provide a landing area for Allied force to be known as "Force C" and supplies to be brought in, allowing "Force C" and the maquis to attack the Wehrmacht from the rear.[141] The Supreme Headquarters of the Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) had rejected this plan under the grounds that the disparity between the firepower and training of the Wehrmacht vs. the maquisards meant that the Resistance would be unable to hold their own in sustained combat.[141] The maquis unaware of this tried to seize "redoubts" several times in 1944 with disastrous results. Starting in late January 1944, a group of maquisards led by Théodose Morel (codename Tom) began to assemble on the Glières Plateau near Annecy in the Haute-Savoie.[146] By February 1944, the maquisards numbered about 460 and had only light weapons, but received much media attention with the Free French issuing a press release in London saying "In Europe there are three countries resisting: Greece, Yugoslavia and the Haute-Savoie".[146] The Vichy state sent the Groupes Mobiles de Réserve to evict the maquis from the Glières plateau and were repulsed.[146] After Morel had been killed by a French policeman during a raid, command of the Maquis des Glières was assumed by Captain Maurice Anjot. In March 1944, the Luftwaffe started to bomb the maquisards on the Glières plateau and on 26 March 1944 the Germans sent in an Alpine division of 7,000 men together with various SS units and about 1,000 miliciens, making for about 10,000 men supported by artillery and air support which soon overwhelmed the maquisards whose lost about 150 killed in action and another 200 captured who were then shot.[146] Anjot knew the odds against his maquis band were hopeless, but decided to take a stand to uphold French honor.[147] Anjot himself was one of the maquisards killed on the Glières plateau.[147]

In February 1944, all of the Resistance governments agreed to accept the authority of the Free French government based in Algiers (until 1962 Algeria was considered to be part of France) and the Resistance was renamed FFI (Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur-Forces of the Interior).[137] The Germans refused to accept the Resistance as legitimate opponents and any résistant captured faced the prospect of torture and/or execution as the Germans maintained that the Hague and Geneva conventions did not apply to the Resistance. By designating the Resistance as part of the French armed forces was intended to provide the Resistance with legal protection and allow the French to threaten the Germans with the possibility of prosecution for war crimes.[148] The designation did not help. For example, the résistante Sindermans was arrested in Paris on 24 February 1944 after she was found to be carrying forged papers.[106] As she recalled: "Immediately, they handcuffed me and took me to be interrogated. Getting no reply, they slapped in the face with such force that I fell from the chair. Then they whipped me with a rubber hose, full in the face. The interrogation began at 10 o'clock in the morning and ended at 11 o'clock that night. I must tell you I had been pregnant for three months".[106]