Women in Greece

The status and characteristics of ancient and modern-day women in Greece evolved from the events that occurred in the history of Greece. According to Michael Scott, in his article "The Rise of Women in Ancient Greece" (History Today), "place of women" and their achievements in ancient Greece was best described by Thucidydes in this quotation: that "The greatest glory [for women] is to be least talked about among men, whether in praise or blame."[4] However, the status of Greek women has undergone charge and more advancement upon the onset of the twentieth century. In 1952, they received their right to vote,[5] which led to their earning places and job positions in businesses and in the government of Greece; and they were able to maintain their right to inherit property, even after being married.[6]

Ellie Lambeti, Greek actress | |

| General Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Maternal mortality (per 100,000) | 3 (2010) |

| Women in parliament | 21.0% (2013) |

| Women over 25 with secondary education | 59.5% (2012) |

| Women in labour force | 47.3% (employment rate OECD definition, 2019)[1] |

| Gender Inequality Index[2] | |

| Value | 0.119 |

| Rank | 32nd out of 191 |

| Global Gender Gap Index[3] | |

| Value | 0.689 (2022) |

| Rank | 100th out of 146 |

| Part of a series on |

| Women in society |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

Women in ancient Greece

Social, legal and political status

Although mostly women lacked political and equal rights in ancient Greece, they enjoyed a certain freedom of movement until the Archaic age.[7] Records also exist of women in ancient Delphi, Gortyn, Thessaly, Megara and Sparta owning land, the most prestigious form of private property at the time.[8] However, after the Archaic age, women's status got worse, and laws on gender segregation were implemented.[7]

Women in Classical Athens had no legal personhood and were assumed to be part of the oikos (household) headed by the male kyrios (master). In Athenian society, the legal term of a wife was known as a damar, a word that is derived from the root meaning of "to subdue" or "to tame".[9] Until marriage, women were under the guardianship of their fathers or other male relatives; once married, the husband became a woman's kyrios. While the average age to get married for men was around 30, the average age for women was 14. This system was implemented as a way to ensure that girls were still virgins when they wed; it also made it possible for husbands to choose who their wife's next husband was going to be before he died.[10] As women were barred from conducting legal proceedings, the kyrios would do so on their behalf.[11] Athenian women had limited right to property and therefore were not considered full citizens, as citizenship and the entitlement to civil and political rights was defined in relation to property and the means to life.[12] If there was a death of the head of a household with no male heir to inherit, then a daughter may become the provisional beret of the property, known as epikleros (roughly translated to an heiress). Later, it was common for most of the women to marry a close relative of her father if she became adjunct to that property.[13] However, women could acquire rights over property through gifts, dowry and inheritance, though her kyrios had the right to dispose of a woman's property.[14] Athenian women could enter into a contract worth less than the value of a "medimnos of barley" (a measure of grain), allowing women to engage in petty trading.[11] Slaves, like women, were not eligible for full citizenship in ancient Athens, though in rare circumstances they could become citizens if freed. The only permanent barrier to citizenship, and hence full political and civil rights, in ancient Athens was gender. No women ever acquired citizenship in ancient Athens, and therefore women were excluded in principle and practice from ancient Athenian democracy.[15]

By contrast, Spartan women enjoyed a status, power, and respect that was unknown in the rest of the classical world. Although Spartan women were formally excluded from military and political life they enjoyed considerable status as mothers of Spartan warriors. As men engaged in military activity, women took responsibility for running estates. Following protracted warfare in the 4th century BC Spartan women owned approximately between 60% and 70% of all Spartan land and property.[16][17] By the Hellenistic Period, some of the wealthiest Spartans were women.[18] They controlled their own properties, as well as the properties of male relatives, who were away with the army.[16] Spartan women rarely married before the age of 20, and unlike Athenian women who wore heavy, concealing clothes and were rarely seen outside the house, Spartan women wore short dresses and went where they pleased.[19] Girls as well as boys received an education, and young women as well as young men may have participated in the Gymnopaedia ("Festival of Nude Youths").[16][20] Despite relatively greater mobility for Spartan women, their role in politics was just as the same as Athenian women: they could not take part in it. Men forbade them from speaking at assemblies and segregated them from any political activities. Aristotle also thought Spartan women's influence was mischievous and argued that the greater legal freedom of women in Sparta caused its ruin.[21]

Athens was also the cradle of philosophy at the time and anyone could become a poet, scholar, politician or artist except women.[21] Historian Don Nardo stated "throughout antiquity most Greek women had few or no civil rights and many enjoyed little freedom of choice or mobility".[21] During the Hellenistic period in Athens, the famous philosopher Aristotle thought that women would bring disorder, evil, and were "utterly useless and caused more confusion than the enemy."[21] Because of this, Aristotle thought keeping women separate from the rest of the society was the best idea.[21] This separation would entail living in homes called a gynaeceum while looking after the duties in the home and having very little exposure with the male world.[21] This was also to protect women's fertility from men other than her husband so her fertility can ensure their legitimacy of their born lineage.[21] Athenian women were also educated very little except home tutorship for basic skills such as spin, weave, cook and some knowledge of money.[21]

In Gortyn, women had a much better position than in Greece. Every woman, including slaves, was subject of protection. Gortyne women, as well as Spartan women, were able to enter into a legal agreement and appear before the court. She had special property that her husband did not have at his disposal, and in relation to that, she could appear in court and take oaths. Husband and wife had the right to divorce equally. A free divorced woman could throw her child into the river. Daughters in Gortyn inherited half of the movables that her brothers would receive. Epicleros (in Sparta and Gortyn, they were called patrouchoi) had a certain freedom of choice regarding her husband. Namely, if a woman was already married with children, and became an epicler, she could choose whether to divorce her husband or not. But a married woman without children who becomes an epicler, had no choice but to divorce and marry according to the regulations. The heir's daughter could not dispose of the inherited property, she could exceptionally sell it or pledge it in the amount of the debt for the payment of her late father's creditor.

Plato acknowledged that extending civil and political rights to women would substantively alter the nature of the household and the state.[22] Aristotle, who had been taught by Plato, denied that women were slaves or subject to property, arguing that "nature has distinguished between the female and the slave", but he considered wives to be "bought". He argued that women's main economic activity is that of safeguarding the household property created by men. According to Aristotle the labour of women added no value because "the art of household management is not identical with the art of getting wealth, for the one uses the material which the other provides".[23]

Contrary to these views, the Stoic philosophers argued for equality of the sexes, sexual inequality being in their view contrary to the laws of nature.[24] In doing so, they followed the Cynics, who argued that men and women should wear the same clothing and receive the same kind of education.[24] They also saw marriage as a moral companionship between equals rather than a biological or social necessity, and practiced these views in their lives.[24] The Stoics adopted the views of the Cynics and added them to their own theories of human nature, thus putting their sexual egalitarianism on a strong philosophical basis.[24]

Right to divorce

Despite the harsh limits on women's freedoms and rights in ancient Greece, their rights in context of divorce were fairly liberal. Marriage could be terminated by mutual consent or action taken by either spouse. If a woman wanted to terminate her marriage, she needed the help of her father or other male relative to represent her, because as a woman she was not considered a citizen of Greece. If a man wanted a divorce however, all he had to do was throw his spouse out of his house. A woman's father also had the right to end the marriage. In the instance of a divorce, the dowry was returned to the woman's guardian (who was usually her father) and she had the right to retain ½ of the goods she had produced while in the marriage. If the couple had children, divorce resulted in paternal full custody, as children are seen as belonging to his household. While the laws regarding divorce may seem relatively fair considering how little control women had over most aspects of their lives in ancient Greece, women were unlikely to divorce their husbands because of the damage it would do to their reputation.[10] As women were barred from conducting legal proceedings, the kyrios would do so on their behalf.[11]

Education

In ancient Greece, education encompassed cultural training in addition to formal schooling. Young Greek children, but only the boys, were taught reading, writing, and arithmetic by a litterator (the equivalent of a modern elementary school teacher). If a family did not have the funds for further education, the boy would begin working for the family business or train as an apprentice, while a girl was expected to stay home and help her mother to manage the household. If a family had the money, parents could continue to educate their sons for their family. This next level of schooling included learning how to speak correctly and interpret poetry, and was taught by a Grammaticus. Music, mythology, religion, art, astronomy, philosophy, and history were all taught as segments of this level of education.[25]

Arts

Lysistrata (/laɪˈsɪstrətə/ or /ˌlɪsəˈstrɑːtə/; Attic Greek: Λυσιστράτη, Lysistrátē, "Army Disbander") is an ancient Greek comedy written by Aristophanes, originally performed in classical Athens in 411 BCE.[26] The play depicts women's extraordinary mission to end the Peloponnesian War between Greek City states by denying all the men of the land any womanly sexual pleasures, which was the only thing the men desired. Lysistrata persuades the women of the warring cities to withhold sexual privileges from their husbands and lovers as a means of forcing the men to negotiate peace. This was a unique strategy, however, that inflames the battle between the sexes. Lysistrata women were going to attempt to end the war by capitalizing on their sexuality[27] This play depicts the status of women in 411 BCE, and considering that the play was a comedy, it suggested that women have limited power and would be ridiculous for them to take a stand.

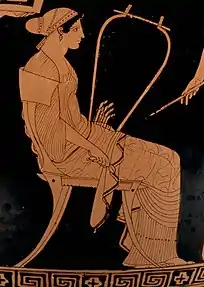

There is not much surviving evidence of the roles of women within the Ancient Greece society. The majority of our sources come from pottery found which displayed the everyday lives of Ancient Greek citizens. Such pottery provides a medium which allows us to examine women's roles which were generally depicted as goddesses, keepers of domestic life, or whores through the lens of Greek ideology. "Scenes of adornment within vase painting are a window into the women’s sphere, though they were not entirely realistic, rather, a product of the voyeuristic and romanticized image of womanhood rooted in the male gaze".[28] Most women are frequently depicted as "sexual objects" in Ancient Greek pottery, thus providing context for the sexual culture of Ancient Greece.[29] A majority of vase scenes portray women inside their houses, there is a common presence of columns suggests that women spent much of their time in the courtyard of the house. The courtyard is the one place where they could regularly enjoy the outdoors and get fresh air. A majority of Greek cooking equipment was small and light and could easily be set up there. It can be inferred that during sunny weather, women probably sat in the roofed and shaded areas of the courtyard, for the ideal in female beauty was a pale complexion.[30]

Women in the Greek War of Independence

Amongst the Greek warriors in the Greek War of Independence, there were also women, such as Laskarina Bouboulina. Bouboulina, also known as kapetanissa (captain/admiral) in 1821 raised on the mast of Agamemnon her own Greek flag and sailed with eight ships to Nafplion to begin a naval blockade. Later she took part also in the naval blockade and capture of Monemvasia and Pylos.

Another heroine was Manto Mavrogenous. From a rich family, she spent all her fortune for the Hellenic cause. Under her encouragement, her European friends contributed money and guns to the revolution. She moved to Nafplio in 1823, in order to be in the core of the struggle, leaving her family as she was despised even by her mother because of her choices. Soon, she became famous around Europe for her beauty and bravery.

Contemporary period

During the past decades, the position of women in Greek society has changed dramatically. Efharis Petridou was the first female lawyer in Greece; in 1925 she joined the Athens Bar Association.[31][32] In 1955, women were first allowed to become judges in Greece.[31] In 1983, a new family law was passed, which provided for gender equality in marriage, and abolished dowry and provided for equal rights for "illegitimate" children.[33][34][35] Adultery was also decriminalised in 1983. The new family law provided for civil marriage and liberalised the divorce law. In 2006, Greece enacted Law 3500/2006 -"For combating domestic violence"- which criminalised domestic violence, including marital rape.[36] Law 3719/2008 further dealt with family issues, including Article 14 of the law, which reduced the separation period (necessary before a divorce in certain circumstances) from 4 years to 2 years.[37] Greece also ratified the Council of Europe Convention on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings in 2014.[38] As of 2014, there are 21.0% women in parliament.[39]

Family dynamics remain, however, conservative. The principal form of partnership is marriage, and extramarital childbearing and long-term cohabitation are not widespread. For instance, in 2015 Greece had the lowest percentage of births outside marriage in the European Union, at only 8.8%.[40] Greece has a low fertility rate, at 1.33 number of children per woman (in 2015), lower than the replacement rate of 2.1.[41]

Quality of life

.jpg.webp)

In ancient Greece, Athenian women compensated for their legal incapacities by cultivating the trust of men. They would do this by treating the closest allies to them implemental, creating affectionate relationships.[42] At the expense of the individual several women in ancient Greece struggled in their personal life and their public life, from our perspective there is an emphasis on the nuclear, patriarchal Oikos (households).[13] At home a majority of the women had almost no power, always answering to the man of the household, women often hid while guests were over. Women were often designated to the upper floors, particularly to stay away from the street door and to be away from the semipublic space where the kyrios (master) would entertain his friends.[43][44]

Women were also responsible to maintain the household, fetch water from fountain houses, help organize finances and weave their cloth and clothing for their families. Starting at the young age of seven girls were entrusted with the beginning of weaving one of the most famous Athenian textiles, the peplos (robe) for the holy statue of Athena on the Acropolis. This was an elaborate, very patterned cloth, the design of which traditionally included a battle between the gods and the giants. It took nine months to complete it, and many women participated in its creation.[44] Athenian women and younger girls spent most of their time engaged in the activity of manufacturing textiles from raw materials, these materials were commonly wool.[44] Ischomachos claimed to Socrates that he brought home his fourteen-year-old wife, she had great abilities to work with wool, make clothes and supervise the spinning performed by the women slaves.

See also

References

- "LFS by sex and age - indicators".

- "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORTS. Retrieved 11 November 2022.

- "Global Gender Gap Report 2022" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 27 February 2023.

- Scott, Michael. The Rise of Women in Ancient Greece, History Today, Volume: 59 Issue: 11 2009

- Kerstin Teske: teske@fczb.de. "European Database: Women in Decision-making – Country Report Greece". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Hitton, Shanti. Social Culture of Greece, Travel Tips, USA Today

- Nardo, Don (2000). Women of Ancient Greece. San Diego: Lucent Books. p. 28.

- Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women's equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8135-2905-9.

- Keuls, Eva (1985). The Rein of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens (1st ed.). Harper & Row.

- Kirby, John T. "Marriage". go.galegroup.com. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece. Harvard University Press. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-674-95473-1.

- Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women's equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-8135-2905-9.

- Rotroff, Susan (2006). Women in the Athenian Agora. ASCSA. pp. 10, 11, 12, 13.

- Blundell, Sue (1995). Women in ancient Greece. Harvard University Press. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-674-95473-1.

- Robinson, Eric W. (2004). Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 302. ISBN 978-0-631-23394-7.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Goddess, Whores, Wives, and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1975. p. 60-62

- Tierney, Helen (1999). Women's studies encyclopaedia. Vol. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 609–610. ISBN 978-0-313-31072-0.

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Spartan Women. Oxford University Press, 2002. p. 137

- Pomeroy, Sarah B. Spartan Women. Oxford University Press, 2002. p. 134

- Pomeroy 2002, p. 34

- Pry, Kay O (2012). "Social and Political Roles of Women in Athens and Sparta". Sabre and Scroll. 1 (2).

- Robinson, Eric W. (2004). Ancient Greek democracy: readings and sources. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-631-23394-7.

- Gerhard, Ute (2001). Debating women's equality: toward a feminist theory of law from a European perspective. Rutgers University Press. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-0-8135-2905-9.

- Colish, Marcia L. (1990). The Stoic Tradition from Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages: Stoicism in classical Latin literature. BRILL. pp. 37–38. ISBN 90-04-09327-3., 9789004093270

- Kirby, Ed T. "Education". Gale Virtual Reference Library. Gale Group. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Lysistrata – Aristophanes | Summary, Characters & Analysis | Classical Literature". Classical Literature. November 2019.

- Luo, Cynthia (Spring 2012). "Women and War: Power Play from Lysistrata to the Present". Honors Scholar Theses.

- Blundell, Sue (Spring–Summer 2008). "Women's Bonds, Women's Pots: Adornment Scenes in Attic Vase Painting". Phoenix. 62 (1/2): 115–144. JSTOR 25651701.

- Ettinger, Grace (December 2019). "The Portrayal Of Women In Ancient Greek Pottery". The Pigeon Press.

- Konstan, David (2014). Beauty - The Fortunes of an Ancient Greek Idea. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 30–35. ISBN 978-0-19-992726-5.

- Buchanan, Kelly (6 March 2015). "Women in History: Lawyers and Judges | In Custodia Legis: Law Librarians of Congress". Blogs.loc.gov. Retrieved 9 February 2018.

- "Το Γυναικείο Κίνημα στην Ελλάδα | segth.gr". segth.gr. Retrieved 17 October 2017.

- Marcos, Anastasios C, and Bahr, Stephen J. 2001 Hellenic (Greek) Gender Attitudes. Gender Issues. 19(3):21–40.

- "AROUND THE WORLD; Greece Approves Family Law Changes". The New York Times. 26 January 1983.

- Demos, Vasilikie. (2007) “The Intersection of Gender, Class and Nationality and the Agency of Kytherian Greek Women.” Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association. 11 August.

- "Combating domestic violence :: General Secretariat for Gender Equality". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "Consideration of reports submitted by States parties under article 18 of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women" (PDF). United Nations. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- "Liste complète". Bureau des Traités. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Women in Parliaments: World Classification".

- "TGM - Eurostat".

- "TGM - Eurostat".

- Johnstone, Steven (October 2003). "Women, Property, and Surveillance in Classical Athens". Classical Antiquity. 22 (2): 247–274. doi:10.1525/ca.2003.22.2.247.

- Lysias Atheniensis Kr. e. 450?-380? (2000). Lysias. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292781652. OCLC 1087655989.

- Rotroff, Susan (2006). Women in the Athenian Agora. ASCSA. pp. 28, 32, 36.

Further reading

- Dirven, Lucinda; Icks, Martijn; Remijsen, Sofie, eds. (13 February 2023). The Public Lives of Ancient Women (500 BCE-650 CE). Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-53451-3.

External links

- The Rise of Women in Ancient Greece by Michael Scott, published in History Today Volume: 59 Issue: 11 2009

- What Greece is Really Like (for Women) A Personal Viewpoint by Stephanie Kordas

- The Way Greeks Live Now, The New York Times

- Uporedna pravna tradicija by Sima Avramović and Vojislav Stanimirović