Hamdan Qarmat

Hamdan Qarmat ibn al-Ash'ath (Arabic: حمدان قرمط بن الأشعث, romanized: Ḥamdān Qarmaṭ ibn al-Ashʿath; fl. c. 874–899 CE) was the eponymous founder of the Qarmatian sect of Isma'ilism. Originally the chief Isma'ili missionary (dā'ī) in lower Iraq, in 899 he quarreled with the movement's leadership at Salamiya after it was taken over by Sa'id ibn al-Husayn (the future first Fatimid Caliph), and with his followers broke off from them. Hamdan then disappeared, but his followers continued in existence in the Syrian Desert and al-Bahrayn for several decades.

Hamdan Qarmat ibn al-Ash'ath | |

|---|---|

حمدان قرمط بن الأشعث | |

| Personal | |

| Born | Furat Badaqla |

| Died | 899 or later |

| Religion | Shi'a Islam |

| Denomination | Isma'ilism |

| Sect | Qarmatians |

Life

Hamdan's early life is unknown, except that he came from the village of al-Dur in the district of Furat Badaqla, east of Kufa.[1] He was originally an ox-driver, employed in carrying goods. He enters the historical record with his conversion to the Isma'ili doctrine by the missionary (dā'ī) al-Husayn al-Ahwazi.[1][2] According to the medieval sources about his life, this took place in or around AH 261 (874/75 CE) or AH 264 (877/78 CE).[1][2]

His surname "Qarmat" is considered as being probably of Aramaic origin. Various forms and meanings are recorded in the sources: according to al-Tabari, his name was Karmītah, "red-eyed"; al-Nawbakhti and Nizam al-Mulk provide the diminutive Qarmāṭūya; others suggest that his name meant "short-legged".[1][3] It is traditionally considered that Hamdan's followers were named the Qarāmiṭa (singular Qarmaṭī), "men of Qarmat", after him.[1][4] However, the Twelver Shi'a scholar al-Fadl ibn Shadhan, who died in 873/74, is known to have written a refutation of "Qarmatian" doctrines. This means that either Hamdan had become active several years before the date recorded in the sources, or alternatively that he took his surname from the sect, rather than the other way round.[4][5]

Missionary activity

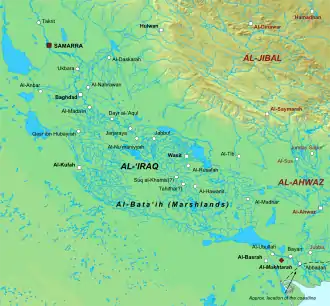

The dā'ī al-Husayn al-Ahwazi had been sent by the Ismai'li leadership at Salamiya, and when he died (or left the area), Hamdan assumed the leadership of Isma'ili missionary activity in the rural environs (sawād) of Kufa and southern Iraq. He soon moved his residence to the town of Kalwadha, south of Baghdad, and rapidly won many new converts among the peasantry and the Bedouin.[1][4] His success was aided by the turmoil of the time. The Abbasid Caliphate was enfeebled, and Iraq was in chaos due to the Zanj Revolt. At the same time, the mainstream Twelver Shi'a adherent were becoming increasingly dissatisfied due to the political quietism of their leadership, as well as by the vacuum left by the death of the eleventh imam Hasan al-Askari and the supposed "occultation" of the twelfth imam, Muhammad al-Mahdi, in 874. In this climate, the millennialism of the Isma'ilis, who preached the imminent return of the messiah or mahdī, was very attractive to dissatisfied Twelvers.[4]

His most prominent disciple and aide was his brother-in-law Abu Muhammad Abdan, who "enjoyed a high degree of independence" (Daftary) and appointed his own dā'īs in Iraq, Bahrayn and southern Persia.[6][4] Among the men trained and sent to missions as dā'īs by Hamdan and Abu Muhammad were Abu Sa'id al-Jannabi (Persia and Bahrayn), Ibn Hawshab and Ali ibn al-Fadl al-Jayshani (to the Yemen), as well as Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i, who later helped convert the Kutama in Ifriqiya and opened the way to the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate.[6] According to the 11th-century Sunni heresiologist Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi, al-Ma'mun, a dā'ī active in southern Persia, was a brother of Hamdan.[6]

Hamdan's agents collected taxes from the converts, including a one-fifth tax on all income (the khums), to be reserved for the mahdī.[1][4] Although Hamdan corresponded with the Salamiya group, their identity remained a secret, and Hamdan was able to pursue his own policy locally. Thus in 880 his numbers were large enough to make overtures for an alliance with the leader of the Zanj, Ali ibn Muhammad, who rebuffed the offer.[4] In 890/91, a fortified refuge (dār al-hijra) was established by Hamdan for his supporters near Kufa.[7]

For several years following the suppression of the Zanj Revolt in 883, Abbasid authority was not firmly re-established in the sawād. Only in 891/92 did reports from Kufa denouncing this "new religion" and reporting on mounting Qarmatian activity begin to cause concern in Baghdad. However, no action was taken against them at the time. As this group was the first to come to the attention of the Abbasid authorities, the label of "Qarmatians" soon came to be applied by Sunni sources to Ismai'li populations in general, including those were not proselytized by Hamdan.[1][8]

Doctrine

No direct information on the doctrine preached by Hamdan and Abu Muhammad is known, but modern scholars like Farhad Daftary consider it to have been, in all likelihood, the same as that propagated at the time from Salamiya, and described in the writings of al-Nawbakhti and Ibn Babawayh.[9] In essence they heralded the imminent return of the seventh imam, Muhammad ibn Isma'il as the mahdī, and thus the start of a new era of justice; the mahdī would proclaim a new law, superseding Islam, and reveal the "hidden" or "inner" (bāṭin) truths of the religion to his followers. Until then, this knowledge was restricted, and only those initiated in the doctrine could access part of it. As a result of these beliefs, the Qarmatians often abandoned traditional Islamic law and ritual. Contemporary mainstream Islamic sources claim that this led to lascivious behaviour among them, but this is not trustworthy given their hostile stance towards Qarmatians.[1]

Split with Salamiya and possible reconciliation

| Part of a series on Islam Isma'ilism |

|---|

|

|

|

In 899, following the death of the previous leader of the sect at Salamiya, Sa'id ibn al-Husayn, the future founder of the Fatimid Caliphate, became the leader. Soon, he began making alterations to the doctrine, which worried Hamdan. Abu Muhammad went to Salamiya to investigate the matter, and learned that Sa'id claimed that the expected mahdī was not Muhammad ibn Isma'il, but Sa'id himself. This caused a major rift in the movement, as Hamdan denounced the leadership in Salamiya, gathered the Iraqi dā'īs and ordered them to cease the missionary effort. Shortly after this Hamdan "disappeared" from his headquarters at Kalwadha.[10][11] The 13th-century anti-Isma'ili writer Ibn Malik reports the rather unreliable information that he was killed in Baghdad,[1][12] while Ibn Hawqal, who wrote in the 970s, claims that he reconciled with Sa'id and became a dā'ī for the Fatimid cause under the name of Abu Ali Hasan ibn Ahmad. According to Wilferd Madelung, given Ibn Hawqal's Fatimid sympathies and friendship with Abu Ali's son, "his information may well be reliable".[6][12]

Abu Ali Hasan claimed descent from Muslim ibn Aqil ibn Abi Talib and settled at Fustat, the capital of Egypt. From there he attempted to regain the support of Hamdan's followers, but those in Iraq and Bahrayn refused; Ibn Hawshab in Yemen and Abu Abdallah al-Shi'i in Ifriqiya, however, accepted his authority, and used him as an intermediary with Sa'id in Salamiya. When Sa'id fled from Syria and spent a year in Fustat in 904/905, Abu Ali was responsible for their safety.[6] Following the establishment of the Fatimid Caliphate in 909, Abu Ali visited Sa'id, now caliph, in Ifriqiya, and was sent to spread Islam in Byzantine Asia Minor, where he was captured and imprisoned for five years. After his release he returned to Ifriqiya, where Sa'id's son and heir apparent, the future caliph al-Qa'im bi-Amr Allah, appointed him as chief dāʿi, with the title "Gate of Gates" (bāb al-abwāb).[lower-alpha 1] In this post, he composed works explaining Fatimid doctrine; in the Ummahāt al-Islām, he refuted use of philosophy among the anti-Fatimid eastern Isma'ilis (including in the teachings of Abu Muhammad Abdan), and instead "asserted the primacy of the principle of taʾwil, esoteric interpretation, in Isma'ili religious teaching". He died in 933, and his son Abu'l-Hasan Muhammad succeeded him as chief dāʿi.[6]

Subsequent history of the Qarmatian movement

After Hamdan's disappearance, the term "Qarmatians" was retained by all Isma'ilis who refused to recognize the claims of Sa'id, and subsequently of the Fatimid dynasty.[5] At times it was also applied by non-Isma'ilis in a pejorative sense to the supporters of the Fatimids as well.[5] Abu Muhammad was murdered in the same year at the instigation of Zakarawayh ibn Mihrawayh, apparently on the instructions of Salamiya.[11][14] Hamdan's and Abu Muhammad's followers threatened to kill Zakarawayh, who himself was forced to hide.[14] The dā'īs appointed by Abu Muhammad then resumed their work, denouncing the claims of Sa'id in Salamiya, and continuing the Qarmatian movement, although Abu Muhammad was often cited as the source of their religious and philosophical works.[15] A Qarmatian movement (the so-called Baqliyya) survived in lower Iraq for several decades thereafter, with their teachings ascribed largely to Abu Muhammad.[12]

In the Syrian Desert and lower Iraq, Zakarawayh soon assumed the initiative, at first covertly. Through his sons, Zakarawayh sponsored a great uprising in Syria 902–903, that was brought to an end in the Battle of Hama in November 903; although probably designed to bring about a pro-Fatimid revolution, the large-scale Abbasid reaction it precipitated and the attention it brought on him forced Sa'id to abandon Salamiya for the Maghreb, where he would found the Fatimid state in Ifriqiya. Zakarawayh himself emerged into the open in 906, claiming to be the mahdī, to lead the last Qarmatian attacks on the Abbasids in Iraq, before being defeated and captured early in the next year.[16][17] The Qarmatians had more success in Bahrayn, where Abu Sa'id al-Jannabi, who had been sent to the region c. 886/87 by Hamdan and Abu Muhammad, founded an independent Qarmatian state that became a major threat to the Abbasids in the 10th century.[18] Other Qarmatian groups existed independently in Yemen, Rayy, and Khurasan.[19]

Footnotes

References

- Madelung & Halm 2016.

- Daftary 2007, p. 107.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 107–108.

- Daftary 2007, p. 108.

- Madelung 1978, p. 660.

- Madelung 2003.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 108–109.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 108, 109.

- Daftary 2007, p. 109.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 116–117.

- Madelung 1996, p. 24.

- Daftary 2007, p. 120.

- Bayhom-Daou 2010.

- Daftary 2007, p. 117.

- Madelung 2007.

- Daftary 2007, pp. 122–123.

- Madelung 1978, pp. 660–661.

- Madelung 1978, pp. 661, 662.

- Madelung 1978, p. 661.

Sources

- Bayhom-Daou, Tamima (2010). "Bāb (in Shīʿism)". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Daftary, Farhad (2007). The Ismāʿı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-61636-2.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1978). "Ḳarmaṭī". In van Donzel, E.; Lewis, B.; Pellat, Ch. & Bosworth, C. E. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume IV: Iran–Kha (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 660–665. OCLC 758278456.

- Madelung, Wilferd (1996). "The Fatimids and the Qarmatīs of Bahrayn". In Daftary, Farhad (ed.). Mediaeval Isma'ili History and Thought. Cambridge University Press. pp. 21–73. ISBN 978-0-521-00310-0.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2003). "ḤAMDĀN QARMAṬ". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XI/6: Ḥājj Sayyāḥ–Harem I. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 634–635. ISBN 978-0-933273-70-2.

- Madelung, Wilferd (2007). "ʿAbdān, Abū Muḥammad". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

- Madelung, Wilferd; Halm, Heinz (2016). "Ḥamdān Qarmaṭ". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.