Haplogroup L-M20

Haplogroup L-M20 is a human Y-DNA haplogroup, which is defined by SNPs M11, M20, M61 and M185. As a secondary descendant of haplogroup K and a primary branch of haplogroup LT, haplogroup L currently has the alternative phylogenetic name of K1a, and is a sibling of haplogroup T (a.k.a. K1b).

| Haplogroup L-M20 | |

|---|---|

| |

| Possible time of origin | 30,000[1] - 43,000 years BP[2] |

| Possible place of origin | Middle East, West Asia, South Asia or Pamir Mountains |

| Ancestor | LT |

| Defining mutations | M11, M20, M61, M185, L656, L863, L878, L879[web 1] |

| Highest frequencies | Syria Raqqa, Balochistan, Northern Afghanistan, Karnataka, Tarkhan, Jats, Kalash, Nuristanis, Burusho, Pashtuns, Lazs, Afshar village, Fascia, Veneto, Southern Tyrol |

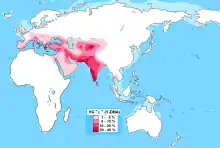

The presence of L-M20 has been observed at varying levels throughout South Asia, peaking in populations native to Balochistan (28%),[3] Northern Afghanistan (25%),[4] and Southern India (19%).[5] The clade also occurs in Tajikistan and Anatolia, as well as at lower frequencies in Iran. It has also been present for millennia at very low levels in the Caucasus, Europe and Central Asia. The subclade L2 (L-L595) has been found in Europe and Western Asia, but is extremely rare.

Phylogenetic tree

There are several confirmed and proposed phylogenetic trees available for haplogroup L-M20. The scientifically accepted one is the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC) one published in Karafet 2008 and subsequently updated. A draft tree that shows emerging science is provided by Thomas Krahn at the Genomic Research Center in Houston, Texas.[web 1] The International Society of Genetic Genealogy (ISOGG) also provides an amateur tree.

This is Thomas Krahn at the Genomic Research Center's Draft tree Proposed Tree for haplogroup L-M20:[web 1]

- L-M20 M11, M20, M61, M185, L656, L863, L878, L879

- L-M22 (L1) M22, M295, PAGES00121

- L-M317 (L1b) M317, L655

- L-L656 (L1b1) L656

- L-M349 (L1b1a) M349

- L-M274 M274

- L-L1310 L1310

- L-L656 (L1b1) L656

- L-L1304 L1304

- L-M27 (L1a1) M27, M76, P329.1, L1318, L1319, L1320, L1321

- L-M357 (L1a2) M357, L1307

- L-PK3 PK3

- L-L1305 L1305, L1306, L1307

- L-M317 (L1b) M317, L655

- L-L595 (L2) L595

- L-L864 L864, L865, L866, L867, L868, L869, L870, L877

- L-M22 (L1) M22, M295, PAGES00121

Origins

L-M20 is a descendant of Haplogroup LT,[6][7] which is a descendant of haplogroup K-M9.[8][7] According to Dr. Spencer Wells, L-M20 originated in the Eurasian K-M9 clan that migrated eastwards from the Middle East, and later southwards from the Pamir Knot into present-day Pakistan and India.[9][10] These people arrived in India approximately 30,000 years ago.[9][10] Hence, it is hypothesized that the first bearer of M20 marker was born either in India or the Middle East.[9] Other studies have proposed either a West Asian or South Asian origin for L-M20 and associated its expansion in the Indus valley to neolithic farmers.[11][12][13][14][15][16] Genetic studies suggest that L-M20 may be one of the haplogroups of the original creators of the Indus Valley Civilisation.[3][17][15] McElreavy and Quintana-Murci, writing on the Indus Valley Civilisation, state that

One Y-chromosome haplogroup (L-M20) has a high mean frequency of 14% in Pakistan and so differs from all other haplogroups in its frequency distribution. L-M20 is also observed, although at lower frequencies, in neighbouring countries, such as India, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Russia. Both the frequency distribution and estimated expansion time (~7,000 YBP) of this lineage suggest that its spread in the Indus Valley may be associated with the expansion of local farming groups during the Neolithic period.[15]

Sengupta et al. (2006) observed three subbranches of haplogroup L: L1-M76 (L1a1), L2-M317 (L1b) and L3-M357 (L1a2), with distinctive geographic affiliations.[5] Almost all Indian members of haplogroup L are L1 derived, with L3-M357 occurring only sporadically (0.4%).[18][19] Conversely in Pakistan, L3-M357 subclade account for 86% of L-M20 chromosomes and reaches an intermediate frequency of 6.8%, overall.[20] L1-M76 occurs at a frequency of 7.5% in India and 5.1% in Pakistan, exhibiting peak variance distribution in the Maharashtra region in coastal western India.[21]

Geographical distribution

In India, L-M20 has a higher frequency among Dravidian castes, but is somewhat rarer in Indo-Aryan castes.[5] In Pakistan, it has highest frequency in Balochistan.[22]

It has also been found at low frequencies among populations of Central Asia and South West Asia (including Arabia, Iraq, Syria, Turkey, Lebanon, Egypt, and Yemen) as well as in Southern Europe (especially areas adjoining the Mediterranean Sea).

Preliminary evidence gleaned from non-scientific sources, such as individuals who have had their Y-chromosomes tested by commercial labs,[web 2] suggests that most European examples of Haplogroup L-M20 might belong to the subclade L2-M317, which is, among South Asian populations, generally the rarest of the subclades of Haplogroup L.[web 2]

India

It has higher frequency among Dravidian castes (ca. 17-19%) but is somewhat rarer in Indo-Aryan castes (ca. 5-6%).[5] The presence of haplogroup L-M20 is quite rare among tribal groups (ca. 5,6-7%) (Cordaux 2004, Sengupta 2006, and Thamseem 2006). However, the Korova tribe of Uttara Kannada in which L-M11 occurs at 68% is an exception.[23]

L-M20 was found at 38% in the Bharwad caste and 21% in Charan caste from Junagarh district in Gujarat.(Shah 2011) It has also been reported at 17% in the Kare Vokkal tribe from Uttara Kannada in Karnataka.(Shah 2011) It is also found at low frequencies in other populations from Junagarh district and Uttara Kannada. L-M20 is the single largest male lineage (36.8%) among the Jat people of Northern India and is found at 16.33% among the Gujar's of Jammu and Kashmir.[17][24] It also occurs at 18.6% among the Konkanastha Brahmins of the Konkan region[25] and at 15% among the Maratha's of Maharashtra.[26] L-M20 is also found at 32.35% in the Vokkaligas and at 17.82% in the Lingayats of Karnataka.[27] L-M20 is also found at 48% among the Kallar (caste), 26% among the Saurashtra people, 20.7% among the Ambalakarar, 16.7% among the Iyengar and 17.2% among the Iyer castes of Tamil Nadu.[28][26] L-M11 is found in frequencies of 8-16% among Indian Jews.[29] L-M20 has an overall frequency of 12% in Punjab.[19] 2% of Siddis have also been reported with L-M11.(Shah 2011) Haplogroup L-M20 is currently present in the Indian population at an overall frequency of ca. 7-15%.[Footnote 1]

Pakistan

The greatest concentration of Haplogroup L-M20 is along the Indus River in Pakistan where the Indus Valley civilization flourished during 3300–1300 BC with its mature period between 2600–1900 BCE. L-M357's highest frequency and diversity is found in the Balochistan province at 28%[22] with a moderate distribution among the general Pakistani population at 11.6% (Firasat et al. 2007)). It is also found in Afghanistan ethnic counterparts as well, such as with the Pashtuns and Balochis. L-M357 is found frequently among Burusho (approx. 12% (Firasat et al. 2007)) and Pashtuns (approx. 7% (Firasat et al. 2007)),

L1a and L1c-M357 are found at 24% among Balochis, L1a and L1c are found at 8% among the Dravidian-speaking Brahui, L1c is found at 25% among Kalash, L1c is found at 15% among Burusho, L1a-M76 and L1b-M317 are found at 2% among the Makranis and L1c is found at 3.6% of Sindhis according to Julie di Cristofaro et al. 2013.[30] L-M20 is found at 17.78% among the Parsis.[31] L3a is found at 23% among the Nuristanis in both Pakistan and Afghanistan.[32]

L-PK3 is found in approximately 23% of Kalash in northwest Pakistan (Firasat et al. 2007).

Middle East and Anatolia

L-M20 was found in 51% of Syrians from Raqqa, a northern Syrian city whose previous inhabitants were wiped out by Mongol genocides and repopulated in recent times by local Bedouin populations and Chechen war refugees from Russia (El-Sibai 2009). In a small sample of Israeli Druze haplogroup L-M20 was found in 7 out of 20 (35%). However, studies done on bigger samples showed that L-M20 averages 5% in Israeli Druze,[Footnote 2] 8% in Lebanese Druze,[Footnote 3] and it was not found in a sample of 59 Syrian Druze. Haplogroup L-M20 has been found in 2.0% (1/50) (Wells 2001) to 5.25% (48/914) of Lebanese (Zalloua 2008).

| Populations | Distribution | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Turkey | 57% in Afshar village, 12% (10/83) in Black Sea Region, 6.6% (7/106) of Turks in Turkey, 4.2% (1/523 L-M349 and 21/523 L-M11(xM27, M349)) | Cinnioğlu 2004, Gokcumen 2008 |

| Iran | 54.9% (42/71) L in Priest Zoroastrian Parsis 22.2% L1b and L1c in South Iran (2/9) 8% to 16% L2-L595, L1a, L1b and L1c of Kurds in Kordestan (2-4/25) 9.1% L-M20 (7/77) of Persians in Eastern Iran 3.4% L-M76 (4/117) and 2.6% L-M317 (3/117) for a total of 6.0% (7/117) haplogroup L-M20 in Southern Iran 3.0% (1/33) L-M357 in Northern Iran 4.2% L1c-M357 of Azeris in East Azeris (1/21) 4.8% L1a and L1b of Persians in Esfahan (2/42) | Regueiro 2006, Di Cristofaro 2013, Malyarchuk 2013 |

| Syria | 51.0% (33/65) of Syrians in Raqqa, 31.0% of Eastern Syrians | El-Sibai 2009 |

| Laz | 41.7% (15/36) L1b-M317 | |

| Saudi Arabians | 15.6% ( 4/32 of L-M76 and 1/32 of L-317 ) 1.91% (2/157=1.27% L-M76 and 1/157=0.64% L-M357) | Abu-Amero 2009 |

| Kurds | 3.2% of Kurds in Southeast Turkey | Flores 2005 |

| Iraq | 3.1% (2/64) L-M22 | Sanchez 2005 |

| Armenians | 1.63% (12/734) to 4.3% (2/47) | Weale 2001 and Wells 2001 |

| Omanis | 1% L-M11 | Luis 2004 |

| Qataris | 2.8% (2/72 L-M76) | Cadenas 2008 |

| UAE Arabs | 3.0% (4/164 L-M76 and 1/164 L-M357) | Cadenas 2008 |

Afghanistan

A study on the Pashtun male lineages in Afghanistan, found that Haplogroup L-M20, with an overall frequency of 9.5%, is the second most abundant male lineage among them.[33] It exhibits substantial disparity in its distribution on either side of the Hindu Kush range, with 25% of the northern Afghan Pashtuns belonging to this lineage, compared with only 4.8% of males from the south.[33] Specifically, paragroup L3*-M357 accounts for the majority of the L-M20 chromosomes among Afghan Pashtuns in both the north (20.5%) and south (4.1%).[33] An earlier study involving a lesser number of samples had reported that L1c comprises 12.24% of the Afghan Pashtun male lineages.[34][35] L1c is also found at 7.69% among the Balochs of Afghanistan.[34] However L1a-M76 occurs in a much more higher frequency among the Balochs (20[35] to 61.54%),[35] and is found at lower levels in Kyrgyz, Tajik, Uzbek and Turkmen populations.[35]

East Asia

Researchers studying samples of Y-DNA from populations of East Asia have rarely tested their samples for any of the mutations that define Haplogroup L. However, mutations for Haplogroup L have been tested and detected in samples of Balinese (13/641 = 2.0% L-M20), Han Chinese (1/57 = 1.8%),[37] Dolgans from Sakha and Taymyr (1/67 = 1.5% L-M20) and Koreans (3/506 = 0.6% L-M20).[38][39][40]

Europe

An article by O. Semino et al. published in the journal Science (Volume 290, 10 November 2000) reported the detection of the M11-G mutation, which is one of the mutations that defines Haplogroup L, in approximately 1% to 3% of samples from Georgia, Greece, Hungary, Calabria (Italy), and Andalusia (Spain). The sizes of the samples analyzed in this study were generally quite small, so it is possible that the actual frequency of Haplogroup L-M20 among Mediterranean European populations may be slightly lower or higher than that reported by Semino et al., but there seems to be no study to date that has described more precisely the distribution of Haplogroup L-M20 in Southwest Asia and Europe.

| Populations | Distribution | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Fascia, Italy | 19.2% of Fascians L-M20 | |

| Nonstal, Italy | 10% of Nonesi L-M20 | Di Giacomo 2003 |

| Samnium, Italy | 10% of Aquilanis L-M20 | Boattini 2013 |

| Vicenza, Italy | 10% of Venetians L-M20 | Boattini 2013 |

| South Tyrol, Italy | 8.9% of Ladin speakers from Val Badia, 8.3% of Val Badia, 2.9% of Puster Valley, 2.2% of German speakers from Val Badia, 2% of German speakers from Upper Vinschgau, 1.9% of German speakers from Lower Vinschgau and 1.7% of Italian speakers from Bolzano | Pichler 2006 and Thomas 2007. |

| Georgians | 20% (2/10) of Georgians in Gali, 14.3% (2/14) of Georgians in Chokhatauri, 12.5% (2/16) of Georgians in Martvili, 11.8% (2/17) of Georgians in Abasha, 11.1% (2/18) of Georgians in Baghdati, 10% (1/10) of Georgians in Gardabani, 9.1% (1/11) of Georgians in Adigeni, 6.9% (2/29) of Georgians in Omalo, 5.9% (1/17) of Georgians in Gurjaani, 5.9% (1/17) of Georgians in Lentekhi and 1.5% (1/66) L-M357(xPK3) to 1.6% (1/63) L-M11 | Battaglia 2008, Semino 2000 and Tarkhnishvili 2014 |

| Daghestan, Russia | 10% of Chechens in Daghestan, 9.5% (4/42) of Avars, 8.3% (2/24) of Tats, 3.7% (1/27) of Chamalins | Yunusbaev 2006, Caciagli 2009 |

| Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia | 5.9% of Russians L1c-M357 | |

| Estonia | L2-L595 and L1-M22 are found in 5.3%, 3.5%, 1.4% and 0.8% of Estonians | Scozzari 2001 and Lappalainen 2008 |

| Balkarians, Russia | 5.3% (2/38) L-M317 | Battaglia 2008 |

| Portugal | 5.0% of Coimbra | Beleza 2006 |

| Bulgaria | 3.9% of Bulgarians | |

| Flanders | L1a*: 3.17% of Mechelen 2.4% of Turnhout and 1.3% of Kempen. L1b*: 0.74% of West Flanders and East Flanders | Larmuseau 2010 and Larmuseau 2011 |

| Antsiferovo, Novgorod | 2.3% of Russians | |

| East Tyrol, Austria | L-M20 is found in 1.9% of Tyroleans in Region B (Isel, Lower Drau, Defereggen, Virgen, and Kals valley) | |

| Gipuzkoa, Basque Country | L1b is found in 1.7% of Gipuzkoans | Young 2011 |

| North Tyrol, Austria | L-M20 is found in 0.8% of Tyroleans in Reutte |

Subclade distribution

L1 (M295)

L-M295 is found from Western Europe to South Asia.[Footnote 5]

The L1 subclade is also found at low frequencies on the Comoros Islands.[41]

L1a1 (M27)

L-M27 is found in 14.5% of Indians and 15% of Sri Lankans, with a moderate distribution in other populations of Pakistan, southern Iran and Europe, but slightly higher Middle East Arab populations. There is a very minor presence among Siddi's (2%),[42] as well.

L1a2 (M357)

L-M357 is found frequently among Burushos, Kalashas, Jats, and Pashtuns, with a moderate distribution among other populations in Pakistan, Georgia,[43] Chechens,[44] Ingushes,[44] northern Iran, India, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia.

A Chinese study published in 2018 found L-M357/L1307 in 7.8% (5/64) of a sample of Loplik Uyghurs from Qarchugha Village, Lopnur County, Xinjiang.[36]

- L-PK3

L-PK3, which is downstream of L-M357,[45] is found frequently among Kalash.

L1b (M317)

L-M317 is found at low frequency in Central Asia, Southwest Asia, and Europe.

In Europe, L-M317 has been found in Northeast Italians (3/67 = 4.5%)[43] and Greeks (1/92 = 1.1%).[43]

In Caucasia, L-M317 has been found in Mountain Jews (2/10 = 20%[46]), Avars (4/42 = 9.5%,[46] 3%[44]), Balkarians (2/38 = 5.3%),[43] Abkhaz (8/162 = 4.9%,[46] 2/58 = 3.4%[44]), Chamalals (1/27 = 3.7%[46]), Abazins (2/88 = 2.3%[46]), Adyghes (3/154 = 1.9%[46]), Chechens (3/165 = 1.8%[46]), Armenians (1/57 = 1.8%[46]), Lezgins (1/81 = 1.2%[44]), and Ossetes (1/132 = 0.76% North Ossetians,[46] 2/230 = 0.9% Iron[44]).

L-M317 has been found in Makranis (2/20 = 10%) in Pakistan, Iranians (3/186 = 1.6%), Pashtuns in Afghanistan (1/87 = 1.1%), and Uzbeks in Afghanistan (1/127 = 0.79%).[47]

L1b1 (M349)

L-M349 is found in some Crimean Karaites who are Levites.[48] Some of L-M349's branches are found in West Asia, including L-Y31183 in Lebanon, L-Y31184 in Armenia, and L-Y130640 in Iraq. Others are found in Europe, such as L-PAGE116 in Italy, L-FT304386 in Slovenia, and L-FGC36841 in Moldova.[49]

L2 (L595)

L2-L595 is extremely rare, and has been identified by private testing in individuals from Europe and Western Asia.

Two confirmed L2-L595 individuals from Iran were reported in a 2020 study supplementary.[50] Possible but unconfirmed cases of L2 include 4% (1/25) L-M11(xM76, M27, M317, M357) in a sample of Iranians in Kordestan[47] and 2% (2/100) L-M20(xM27, M317, M357) in a sample of Shapsugs,[44] among other rare reported cases of L which don't fall into the common branches.

| Region | Population | n/Sample size | Percentage | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Asia | Azerbaijan | 2/204 | 1 | [51] |

| Central Europe | Germany | 1/8641 | 0.0000115 | [52] |

| Southern Europe | Greece | 1/753 | 0.1 | [53] |

| West Asia | Iran | 2/800 | 0.25 | [54] |

| Southern Europe | Italy | 3/913 | 0.3 | [55] |

Ancient DNA

- Three individuals from Maykop culture c. 3200 BCE were found to belong to haplogroup L2-L595.[56]

- Three individuals who lived in the Chalcolithic era (c. 5700–6250 years BP), found in the Areni-1 ("Bird's Eye") cave in the South Caucasus mountains (present-day Vayots Dzor Province, Armenia), were also identified as belonging to haplogroup L1a. One individual's genome indicated that he had red hair and blue eyes. Their genetic data is listed in the table below.

- Narasimhan et al. (2018) analyzed skeletons from the BMAC sites in Uzbekistan and identified 2 individuals as belonging to haplogroup L1a. One of these specimens was found in Bustan and the other in Sappali Tepe; both ascertained to be Bronze Age sites.[57]

- Skourtanioti et al. (2020) analyzed skeletons from the Alalakh sites in Syria and identified one individual (ALA084) c. 2006-1777 BC as belonging to haplogroup L2-L595.[58]

- One Iron Age individual from Batman in Upper Mesopotamia (present-day Southeastern Turkey) belonged to haplogroup L2-L595.[59]

- An ancient Viking individual that lived in Öland, Sweden circa 847 ± 65 CE was determined to belong to L-L595.[60]

Chalcolithic South Caucasus

| Property | Areni-I | Areni-II | Areni-III |

|---|---|---|---|

| ID | AR1/44 I1634 | AR1/46 I1632 | ARE12 I1407 |

| Y DNA | L1a | L1a1-M27 | L1a |

| Population | Chalcolithic (Horizon III) | Chalcolithic (Horizon III) | Chalcolithic (Horizon II) |

| Language | |||

| Culture | Late Chalcolithic | Late Chalcolithic | Late Chalcolithic |

| Date (YBP) | 6161 ± 89 | 6086 ± 72 | 6025 ± 325 |

| Burial / Location | Burial 2 / Areni-1 Cave | Burial 3 / Areni-1 Cave | Trench 2A, Unit 7, Square S33/T33, Locus 9, Spit 23 / Areni-1 Cave |

| Members / Sample Size | 1/3 | 1/3 | 1/3 |

| Percentage | 33.3% | 33.3% | 33.3% |

| mtDNA | H2a1 | K1a8 | H* |

| Isotope Sr | |||

| Eye color (HIrisPlex System) | Likely Blue | ||

| Hair color (HIrisPlex System) | Likely Red | ||

| Skin pigmentation | Likely light | ||

| ABO Blood Group | Likely O or B | ||

| Diet (d13C%0 / d15N%0) | |||

| FADS activity | |||

| Lactase Persistence | Likely lactose-intolerant | ||

| Oase-1 Shared DNA | |||

| Ostuni1 Shared DNA | |||

| Neanderthal Vi33.26 Shared DNA | |||

| Neanderthal Vi33.25 Shared DNA | |||

| Neanderthal Vi33.16 Shared DNA | |||

| Ancestral Component (AC) | |||

| puntDNAL K12 Ancient | |||

| Dodecad [dv3] | |||

| Eurogenes [K=36] | |||

| Dodecad [Globe13] | |||

| Genetic Distance | |||

| Parental Consanguinity | |||

| Age at Death | 11 ± 2.5 | 15 ± 2.5 | |

| Death Position | |||

| SNPs | |||

| Read Pairs | |||

| Sample | |||

| Source | [61] | ||

| Notes | World’s earliest evidence of footwear and wine making |

Nomenclature

Prior to 2002, there were in academic literature at least seven naming systems for the Y-Chromosome Phylogenetic tree. This led to considerable confusion. In 2002, the major research groups came together and formed the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC). They published a joint paper that created a single new tree that all agreed to use. Later, a group of citizen scientists with an interest in population genetics and genetic genealogy formed a working group to create an amateur tree aiming at being above all timely. The table below brings together all of these works at the point of the landmark 2002 YCC Tree. This allows a researcher reviewing older published literature to quickly move between nomenclatures.

| YCC 2002/2008 (Shorthand) | (α) | (β) | (γ) | (δ) | (ε) | (ζ) | (η) | YCC 2002 (Longhand) | YCC 2005 (Longhand) | YCC 2008 (Longhand) | YCC 2010r (Longhand) | ISOGG 2006 | ISOGG 2007 | ISOGG 2008 | ISOGG 2009 | ISOGG 2010 | ISOGG 2011 | ISOGG 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-M20 | 28 | VIII | 1U | 27 | Eu17 | H5 | F | L* | L | L | L | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| L-M27 | 28 | VIII | 1U | 27 | Eu17 | H5 | F | L1 | L1 | L1 | L1 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

- The Y-Chromosome Consortium tree

This is the official scientific tree produced by the Y-Chromosome Consortium (YCC). The last major update was in 2008. Subsequent updates have been quarterly and biannual. The current version is a revision of the 2010 update.[62]

- Original research publications

The following research teams per their publications were represented in the creation of the YCC Tree.

See also

Footnotes

- see Basu 2003, Cordaux 2004, Sengupta 2006, and Thamseem 2006.

- 12/222 Shlush et al. 2008

- 1/25 Shlush et al. 2008

- In Hammer 2005, see the Supplementary Material.

- FTDNA lab results, May 2011

References

- Learn about Y-chromosome Haplogroup L Genebase Tutorials

- Yfull Tree L Haplogroup YTree v8.09.00 (08 October 2020)

- Mahal 2018.

- Lacau, Harlette; Gayden, Tenzin; Regueiro, Maria; Chennakrishnaiah, Shilpa; Bukhari, Areej; Underhill, Peter A; Garcia-Bertrand, Ralph L; Herrera, Rene J (18 April 2012). "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (10): 1063–1070. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.59. ISSN 1018-4813. PMC 3449065. PMID 22510847.

- Sengupta 2006.

- International Society of Genetic Genealogy, 2015, Y-DNA Haplogroup Tree 2015 (30 May 2015).

- Chiaroni, J.; Underhill, P. A.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L. (December 2009). "Y chromosome diversity, human expansion, drift, and cultural evolution". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106 (48): 20174–49. Bibcode:2009PNAS..10620174C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0910803106. JSTOR 25593348. PMC 2787129. PMID 19920170.

- International Society of Genetic Genealogy, 2015 Y-DNA Haplogroup K and its Subclades – 2015 (5 April 2015).

- Wells, Spencer (20 November 2007). Deep Ancestry: The Landmark DNA Quest to Decipher Our Distant Past. National Geographic Books. pp. 161–162. ISBN 978-1-4262-0211-7.

This part of the M9 Eurasian clan migrated south once they reached the rugged and mountainous Pamir Knot region. The man who gave rise to marker M20 was possibly born in India or the Middle East. His ancestors arrived in India around 30,000 years ago and represent the earliest significant settlement of India.

- Wells, Spencer (28 March 2017). The Journey of Man: A Genetic Odyssey. Princeton University Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 978-0-691-17601-7.

- Qamar, Raheel; Ayub, Qasim; Mohyuddin, Aisha; Helgason, Agnar; Mazhar, Kehkashan; Mansoor, Atika; Zerjal, Tatiana; Tyler-Smith, Chris; Mehdi, S. Qasim (2002). "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan". American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (5): 1107–1124. doi:10.1086/339929. ISSN 0002-9297. PMC 447589. PMID 11898125.

- Zhao, Zhongming; Khan, Faisal; Borkar, Minal; Herrera, Rene; Agrawal, Suraksha (2009). "Presence of three different paternal lineages among North Indians: A study of 560 Y chromosomes". Annals of Human Biology. 36 (1): 46–59. doi:10.1080/03014460802558522. ISSN 0301-4460. PMC 2755252. PMID 19058044.

- Thanseem, Ismail; Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Singh, Vijay Kumar; Bhaskar, Lakkakula VKS; Reddy, B Mohan; Reddy, Alla G; Singh, Lalji (7 August 2006). "Genetic affinities among the lower castes and tribal groups of India: inference from Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA". BMC Genetics. 7: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-7-42. ISSN 1471-2156. PMC 1569435. PMID 16893451.

- Cordaux, Richard; Aunger, Robert; Bentley, Gillian; Nasidze, Ivane; Sirajuddin, S. M.; Stoneking, Mark (3 February 2004). "Independent origins of Indian caste and tribal paternal lineages". Current Biology. 14 (3): 231–235. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.024. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 14761656. S2CID 5721248.

- McElreavey, K.; Quintana-Murci, L. (2005). "A population genetics perspective of the Indus Valley through uniparentally-inherited markers". Annals of Human Biology. 32 (2): 154–162. doi:10.1080/03014460500076223. ISSN 0301-4460.

- Thangaraj, Kumarasamy; Naidu, B. Prathap; Crivellaro, Federica; Tamang, Rakesh; Upadhyay, Shashank; Sharma, Varun Kumar; Reddy, Alla G.; Walimbe, S. R.; Chaubey, Gyaneshwer; Kivisild, Toomas; Singh, Lalji (20 December 2010). "The Influence of Natural Barriers in Shaping the Genetic Structure of Maharashtra Populations". PLOS ONE. 5 (12): e15283. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...515283T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0015283. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3004917. PMID 21187967.

- Mahal, David G.; Matsoukas, Ianis G. (20 September 2017). "Y-STR Haplogroup Diversity in the Jat Population Reveals Several Different Ancient Origins". Frontiers in Genetics. 8: 121. doi:10.3389/fgene.2017.00121. ISSN 1664-8021. PMC 5611447. PMID 28979290.

- Sengupta 2006, p. 218.

- Kivisild 2003.

- Sengupta 2006, p. 219.

- Sengupta 2006, p. 220.

- Qamar 2002.

- Shah 2011.

- Sharma, S; Rai, E; Sharma, P; et al. (January 2009). "The Indian origin of paternal haplogroup R1a1* substantiates the autochthonous origin of Brahmins and the caste system". Journal of Human Genetics. 54 (1): 47–55. doi:10.1038/jhg.2008.2. PMID 19158816.

- Kivisild, T; Rootsi, S; Metspalu, M; et al. (February 2003). "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72 (2): 313–32. doi:10.1086/346068. PMC 379225. PMID 12536373.

- Sengupta, S; Zhivotovsky, LA; King, R; et al. (February 2006). "Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 78 (2): 202–21. doi:10.1086/499411. PMC 1380230. PMID 16400607.

- "Analysis of Y-chromosome Diversity in Lingayat and Vokkaliga Populations of Southern India". 2011. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.425.9132.

- Wells 2001.

- Chaubey, Gyaneshwer (2016). "Genetic affinities of the Jewish populations of India". Scientific Reports. 6: 19166. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619166C. doi:10.1038/srep19166. PMC 4725824. PMID 26759184.

- Di Cristofaro, Julie; Pennarun, Erwan; Mazières, Stéphane; Myres, Natalie M.; Lin, Alice A.; Temori, Shah Aga; Metspalu, Mait; Metspalu, Ene; Witzel, Michael; King, Roy J.; Underhill, Peter A.; Villems, Richard; Chiaroni, Jacques (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e76748. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876748D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.

- Qamar, R; Ayub, Q; Mohyuddin, A; et al. (May 2002). "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 70 (5): 1107–24. doi:10.1086/339929. PMC 447589. PMID 11898125.

- Firasat et al. 2007.

- Lacau, H; Gayden, T; Regueiro, M; Chennakrishnaiah, S; Bukhari, A; Underhill, PA; Garcia-Bertrand, RL; Herrera, RJ (Oct 2012). "Afghanistan from a Y-chromosome perspective". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (10): 1063–70. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.59. PMC 3449065. PMID 22510847.

- Haber, M; Platt, DE; Ashrafian Bonab, M; et al. (2012). "Afghanistan's Ethnic Groups Share a Y-Chromosomal Heritage Structured by Historical Events". PLOS ONE. 7 (3): e34288. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...734288H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0034288. PMC 3314501. PMID 22470552.

- Di Cristofaro, J; Pennarun, E; Mazières, S; Myres, NM; Lin, AA; Temori, SA; Metspalu, M; Metspalu, E; Witzel, M; King, RJ; Underhill, PA; Villems, R; Chiaroni, J (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e76748. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876748D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.

- Liu SH; N, Yilihamu; R Bake (2018). "A study of genetic diversity of three isolated populations in Xinjiang using Y-SNP". Acta Anthropologica Sinica. 37 (1): 146–156.

- Zhong 2010.

- Fedorova 2013.

- Karafet et al. 2010.

- Kim 2011.

- Msaidie, Said; et al. (2011). "Genetic diversity on the Comoros Islands shows early seafaring as major determinant of human biocultural evolution in the Western Indian Ocean" (PDF). European Journal of Human Genetics. 19 (1): 89–94. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2010.128. PMC 3039498. PMID 20700146.

- Shah, AM; Tamang, R; Moorjani, P; Rani, DS; Govindaraj, P; Kulkarni, G; Bhattacharya, T; Mustak, MS; Bhaskar, LV; Reddy, AG; Gadhvi, D; Gai, PB; Chaubey, G; Patterson, N; Reich, D; Tyler-Smith, C; Singh, L; Thangaraj, K (2011). "Indian Siddis: African Descendants with Indian Admixture". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89 (1): 154–61. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.030. PMC 3135801. PMID 21741027.

- Vincenza Battaglia, Simona Fornarino, Nadia Al-Zahery, et al. (2009), "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe." European Journal of Human Genetics (2009) 17, 820–830; doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249; published online 24 December 2008.

- Balanovsky, Oleg; Dibirova, Khadizhat; Dybo, Anna; et al. (October 2011). "Parallel Evolution of Genes and Languages in the Caucasus Region". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (10): 2905–2920. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr126. PMC 3355373. PMID 21571925.

- ISOGG 2016.

- Yunusbayev, Bayazit; Metspalu, Mait; Järve, Mari; et al. (2012). "The Caucasus as an Asymmetric Semipermeable Barrier to Ancient Human Migrations". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 29 (1): 359–365. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr221. PMID 21917723.

- Di Cristofaro, J; Pennarun, E; Mazières, S; Myres, NM; Lin, AA; et al. (2013). "Afghan Hindu Kush: Where Eurasian Sub-Continent Gene Flows Converge". PLOS ONE. 8 (10): e76748. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...876748D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0076748. PMC 3799995. PMID 24204668.

- Brook, Kevin A. (Summer 2014). "The Genetics of Crimean Karaites" (PDF). Karadeniz Araştırmaları (Journal of Black Sea Studies). 11 (42): 69-84 on page 76. doi:10.12787/KARAM859.

- "L-M349 YTree".

- Platt, D.E; Artinian, H.; Mouzaya, F. (2020). "Autosomal genetics and Y-chromosome haplogroup L1b-M317 reveal Mount Lebanon Maronites as a persistently non-emigrating population". Eur J Hum Genet. 29 (4): 581–592. doi:10.1038/s41431-020-00765-x. PMC 8182888. PMID 33273712.

- "Azerbaijan DNA". FamilyTreeDNA. Gene by Gene, Ltd.

- "Germany- YDNA". FamilyTreeDNA. Gene by Gene, Ltd.

- "Greek DNA Project". FamilyTreeDNA. Gene by Gene, Ltd.

- Platt, D.E; Artinian, H.; Mouzaya, F. (2020). "Autosomal genetics and Y-chromosome haplogroup L1b-M317 reveal Mount Lebanon Maronites as a persistently non-emigrating population". Eur J Hum Genet. 29 (4): 581–592. doi:10.1038/s41431-020-00765-x. PMC 8182888. PMID 33273712.

- "L - Y Haplogroup L". FamilyTreeDNA. Gene by Gene, Ltd.

- Chuan-Chao Wang, Sabine Reinhold, Alexey Kalmykov, Antje Wissgott, Guido Brandt, Choongwon Jeong, Olivia Cheronet, Matthew Ferry, Eadaoin Harney, Denise Keating, Swapan Mallick, Nadin Rohland, Kristin Stewardson, Anatoly R. Kantorovich, Vladimir E. Maslov, Vladimira G. Petrenko, Vladimir R. Erlikh, Biaslan Ch. Atabiev, Rabadan G. Magomedov, Philipp L. Kohl, Kurt W. Alt, Sandra L. Pichler, Claudia Gerling, Harald Meller, Benik Vardanyan, Larisa Yeganyan, Alexey D. Rezepkin, Dirk Mariaschk, Natalia Berezina, Julia Gresky, Katharina Fuchs, Corina Knipper, Stephan Schiffels, Elena Balanovska, Oleg Balanovsky, Iain Mathieson, Thomas Higham, Yakov B. Berezin, Alexandra Buzhilova, Viktor Trifonov, Ron Pinhasi, Andrej B. Belinskiy, David Reich, Svend Hansen, Johannes Krause, Wolfgang Haak bioRxiv 322347; doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/322347 Now published in Nature Communications doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08220-8

- "The Genomic Formation of South and Central Asia". bioRxiv: 292581. 31 March 2018. doi:10.1101/292581.

- Skourtanioti, Eirini; Erdal, Yilmaz S.; Frangipane, Marcella; Balossi Restelli, Francesca; Yener, K. Aslıhan; Pinnock, Frances; Matthiae, Paolo; Özbal, Rana; Schoop, Ulf-Dietrich; Guliyev, Farhad; Akhundov, Tufan; Lyonnet, Bertille; Hammer, Emily L.; Nugent, Selin E.; Burri, Marta; Neumann, Gunnar U.; Penske, Sandra; Ingman, Tara; Akar, Murat; Shafiq, Rula; Palumbi, Giulio; Eisenmann, Stefanie; d'Andrea, Marta; Rohrlach, Adam B.; Warinner, Christina; Jeong, Choongwon; Stockhammer, Philipp W.; Haak, Wolfgang; Krause, Johannes (2020). "Genomic History of Neolithic to Bronze Age Anatolia, Northern Levant, and Southern Caucasus". Cell. 181 (5): 1158–1175.e28. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.044. PMID 32470401. S2CID 219105572.

- Lazaridis, Iosif (2022). "The genetic history of the Southern Arc: A bridge between West Asia and Europe". Science. 377 (6609): eabm4247. doi:10.1126/science.abm4247. PMC 10064553. PMID 36007055.

- Margaryan, Ashot (2020). "Population genomics of the Viking world". Nature. 585 (7825): 390–396. Bibcode:2020Natur.585..390M. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2688-8. hdl:10852/83989. PMID 32939067. S2CID 221769227.

- Lazaridis, Iosif; et al. (25 July 2016). "Genomic insights into the origin of farming in the ancient Near East". Nature. 536 (7617): 419–24. Bibcode:2016Natur.536..419L. bioRxiv 10.1101/059311. doi:10.1038/nature19310. PMC 5003663. PMID 27459054.

- "Y-DNA Haplotree". Family Tree DNA uses the Y-Chromosome Consortium tree and posts it on their website.

Sources

- Abu-Amero, K. K.; Hellani, A.; González, A. M.; Larruga, J. M.; Cabrera, V. M.; Underhill, P. A. (2009). "Saudi Arabian Y-Chromosome diversity and its relationship with nearby regions". BMC Genetics. 10: 59. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-10-59. PMC 2759955. PMID 19772609.

- Basu, A.; Mukherjee, N.; Roy, S.; Sengupta, S.; Banerjee, S.; Chakraborty, M.; Dey, B.; Roy, M.; Roy, B.; Bhattacharyya, N. P.; Roychoudhury, S.; Majumder, P. P. (2003). "Ethnic India: A Genomic View, with Special Reference to Peopling and Structure". Genome Research. 13 (10): 2277–90. doi:10.1101/gr.1413403. PMC 403703. PMID 14525929.

- Battaglia, V.; Fornarino, S.; Al-Zahery, N.; Olivieri, A.; Pala, M.; Myres, N. M.; King, R. J.; Rootsi, S.; Marjanovic, D.; Primorac, D.; Hadziselimovic, R.; Vidovic, S.; Drobnic, K.; Durmishi, N.; Torroni, A.; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. S.; Underhill, P. A.; Semino, O. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–30. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMC 2947100. PMID 19107149.

- Mahal, David G.; Matsoukas, Ianis G. (23 January 2018). "The Geographic Origins of Ethnic Groups in the Indian Subcontinent: Exploring Ancient Footprints with Y-DNA Haplogroups". Frontiers in Genetics. 9: 4. doi:10.3389/fgene.2018.00004. ISSN 1664-8021.

- Beleza, S.; Gusmao, L.; Lopes, A.; Alves, C.; Gomes, I.; Giouzeli, M.; Calafell, F.; Carracedo, A.; Amorim, A. (2006). "Micro-Phylogeographic and Demographic History of Portuguese Male Lineages". Annals of Human Genetics. 70 (2): 181–94. doi:10.1111/j.1529-8817.2005.00221.x. PMID 16626329. S2CID 4652154.

- Boattini, Alessio; Castrì, Loredana; Sarno, Stefania; Useli, Antonella; Cioffi, Manuela; Sazzini, Marco; Garagnani, Paolo; De Fanti, Sara; Pettener, Davide; Luiselli, Donata (2013). "MtDNA variation in East Africa unravels the history of afro-asiatic groups". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 150 (3): 375–385. doi:10.1002/ajpa.22212. PMID 23283748.

- Caciagli, L.; Bulayeva, K.; Bulayev, O.; Bertoncini, S.; Taglioli, L.; Pagani, L.; Paoli, G.; Tofanelli, S. (2009). "The key role of patrilineal inheritance in shaping the genetic variation of Dagestan highlanders". Journal of Human Genetics. 54 (12): 689–94. doi:10.1038/jhg.2009.94. PMID 19911015.

- Cadenas, A. M.; Zhivotovsky, L. A.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Underhill, P. A.; Herrera, R. J. (2008). "Y-chromosome diversity characterizes the Gulf of Oman". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16 (3): 374–86. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201934. PMID 17928816.

- Cinnioğlu, C.; King, R.; Kivisild, T.; Kalfoglu, E.; Atasoy, S.; Cavalleri, G. L.; Lillie, A. S.; Roseman, C. C.; Lin, A. A.; Prince, K.; Oefner, P. J.; Shen, P.; Semino, O.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Underhill, P. A. (2004). "Excavating Y-chromosome haplotype strata in Anatolia". Human Genetics. 114 (2): 127–48. doi:10.1007/s00439-003-1031-4. PMID 14586639. S2CID 10763736.

- Cordaux, R.; Aunger, R.; Bentley, G.; Nasidze, I.; Sirajuddin, S. M.; Stoneking, M. (2004). "Independent Origins of Indian Caste and Tribal Paternal Lineages". Current Biology. 14 (3): 231–35. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2004.01.024. PMID 14761656. S2CID 5721248.

- Dulik, Matthew C.; Zhadanov, Sergey I.; Osipova, Ludmila P.; Askapuli, Ayken; Gau, Lydia; Gokcumen, Omer; Rubinstein, Samara; Schurr, Theodore G. (February 2012). "Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosome Variation Provides Evidence for a Recent Common Ancestry between Native Americans and Indigenous Altaians". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 90 (2): 229–246. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.12.014. PMC 3276666. PMID 22281367.

- El-Sibai, M.; Platt, D. E.; Haber, M.; Xue, Y.; Youhanna, S. C.; Wells, R. S.; Izaabel, H.; Sanyoura, M. F.; Harmanani, H.; Bonab, M. A.; Behbehani, J.; Hashwa, F.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Zalloua, P. A.; Genographic, Consortium (2009). "Geographical Structure of the Y-chromosomal Genetic Landscape of the Levant: A coastal-inland contrast". Annals of Human Genetics. 73 (6): 568–81. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2009.00538.x. PMC 3312577. PMID 19686289.

- Fedorova, S. A.; Reidla, M.; Metspalu, E.; Metspalu, M.; Rootsi, S.; Tambets, K.; Trofimova, N.; Zhadanov, S. I.; Kashani, B. H.; Olivieri, A.; Voevoda, M. I.; Osipova, L. P.; Platonov, F. A.; Tomsky, M. I.; Khusnutdinova, E. K.; Torroni, A.; Villems, R. (2013). "Autosomal and uniparental portraits of the native populations of Sakha (Yakutia): implications for the peopling of Northeast Eurasia". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13 (127): 127. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-127. PMC 3695835. PMID 23782551.

- Firasat, S.; Khaliq, S.; Mohyuddin, A.; Papaioannou, M.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Underhill, P. A.; Ayub, Q. (2007). "Y-chromosomal evidence for a limited Greek contribution to the Pathan population of Pakistan". European Journal of Human Genetics. 15 (1): 121–26. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201726. PMC 2588664. PMID 17047675.

- Flores, Carlos; Maca-Meyer, Nicole; Larruga, Jose M.; Cabrera, Vicente M.; Karadsheh, Naif; Gonzalez, Ana M. (2005). "Isolates in a corridor of migrations: a high-resolution analysis of Y-chromosome variation in Jordan". Journal of Human Genetics. 50 (9): 435–441. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0274-4. PMID 16142507.

- Di Giacomo, F.; Luca, F.; Anagnou, N.; Ciavarella, G.; Corbo, R.M.; Cresta, M.; Cucci, F.; Di Stasi, L.; et al. (2003). "Clinal patterns of human Y chromosomal diversity in continental Italy and Greece are dominated by drift and founder effects". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 28 (3): 387–95. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00016-2. PMID 12927125.

- Gokcumen, Omer (2008). Ethnohistorical and Genetic Survey of Four Central Anatolian Settlements. University of Pennsylvania. ISBN 978-0-549-80966-1. Retrieved May 13, 2014.

- Hammer, Michael F.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Park, Hwayong; Omoto, Keiichi; Harihara, Shinji; Stoneking, Mark; Horai, Satoshi (January 2006). "Dual origins of the Japanese: common ground for hunter-gatherer and farmer Y chromosomes". Journal of Human Genetics. 51 (1): 47–58. doi:10.1007/s10038-005-0322-0. PMID 16328082. S2CID 6559289.

- Karafet, T.; Xu, L.; Du, R.; Wang, W.; Feng, S.; Wells, R. S.; Redd, A. J.; Zegura, S. L.; Hammer, M. F. (2001). "Paternal Population History of East Asia: Sources, Patterns, and Microevolutionary Processes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (3): 615–28. doi:10.1086/323299. PMC 1235490. PMID 11481588.

- Karafet, T. M.; Hallmark, B.; Cox, M. P.; Sudoyo, H.; Downey, S.; Lansing, J. S.; Hammer, M. F. (2010). "Major East–West Division Underlies Y Chromosome Stratification across Indonesia". Mol. Biol. Evol. 27 (8): 1833–44. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq063. PMID 20207712.

- Kim, S-H.; Kim, K-C.; Shin, D-J.; Jin, H-J.; Kwak, K-D.; Han, M-S.; Song, J-M.; Kim, W.; Kim, W. (2011). "High frequencies of Y-chromosome haplogroup O2b-SRY465 lineages in Korea: a genetic perspective on the peopling of Korea". Investigative Genetics. 2 (1): 10. doi:10.1186/2041-2223-2-10. PMC 3087676. PMID 21463511.

- Lappalainen, T.; Laitinen, V.; Salmela, E.; Andersen, P.; Huoponen, K.; Savontaus, M.-L.; Lahermo, P. (2008). "Migration Waves to the Baltic Sea Region". Annals of Human Genetics. 72 (3): 337–48. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1809.2007.00429.x. PMID 18294359. S2CID 32079904.

- Larmuseau, M. H. D.; Vanderheyden, N.; Jacobs, M.; Coomans, M.; Larno, L.; Decorte, R. (2010). "Micro-geographic distribution of Y-chromosomal variation in the central-western European region Brabant". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 5 (2): 95–99. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2010.08.020. PMID 21036685.

- Kivisild, T.; Rootsi, S.; Metspalu, M.; Mastana, S.; Kaldma, K.; Parik, J.; Metspalu, E.; Adojaan, M.; Tolk, H.-V.; Stepanov, V.; Gölge, M.; Usanga, E.; Papiha, S. S.; Cinnioğlu, C.; King, R.; Cavalli-Sforza, L.; Underhill, P. A.; Villems, R. (2003). "The Genetic Heritage of the Earliest Settlers Persists Both in Indian Tribal and Caste Populations". American Journal of Human Genetics. 72 (2): 313–332. ISSN 0002-9297.

- Larmuseau, M. H. D.; Ottoni, C.; Raeymaekers, J. A. M.; Vanderheyden, N.; Larmuseau, H. F. M.; Decorte, R. (2011). "Temporal differentiation across a West-European Y-chromosomal cline: Genealogy as a tool in human population genetics". European Journal of Human Genetics. 20 (4): 434–40. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2011.218. PMC 3306861. PMID 22126748.

- Lobov AS, et al. (2009). "Structure of the Gene Pool of Bashkir Subpopulations" (PDF) (in Russian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-16.

- Luis, J. R.; Rowold, D. J.; Regueiro, M.; Caeiro, B.; Cinnioğlu, C.; Roseman, C.; Underhill, P. A.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Herrera, R. J. (2004). "The Levant versus the Horn of Africa: Evidence for Bidirectional Corridors of Human Migrations". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (3): 532–44. doi:10.1086/382286. PMC 1182266. PMID 14973781.

- Malyarchuk, Boris; Derenko, Miroslava; Denisova, Galina; Khoyt, Sanj; Woźniak, Marcin; Grzybowski, Tomasz; Zakharov, Ilya (2013). "Y-chromosome diversity in the Kalmyks at the ethnical and tribal levels". Journal of Human Genetics. 58 (12): 804–811. doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.108. PMID 24132124.

- Pichler, I.; Mueller, J. C.; Stefanov, S. A.; De Grandi, A.; Beu Volpato, C.; Pinggera, G. K.; Mayr, A.; Ogriseg, M.; Ploner, F.; Meitinger, T.; Pramstaller, P. P. (2006). "Genetic Structure in Contemporary South Tyrolean Isolated Populations Revealed by Analysis of Y-Chromosome, mtDNA, and Alu Polymorphisms". Human Biology. 81 (5–6): 875–98. doi:10.3378/027.081.0629. PMID 20504204. S2CID 46073270.

- Qamar, R.; Ayub, Q.; Mohyuddin, A.; Helgason, A.; Mazhar, K.; Mansoor, A.; Zerjal, T.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Mehdi, S. Q. (2002). "Y-Chromosomal DNA Variation in Pakistan". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 70 (5): 1107–24. doi:10.1086/339929. PMC 447589. PMID 11898125.

- Regueiro, M.; Cadenas, A. M.; Gayden, T.; Underhill, P. A.; Herrera, R. J. (2006). "Iran: Tricontinental Nexus for Y-Chromosome Driven Migration". Human Heredity. 61 (3): 132–43. doi:10.1159/000093774. PMID 16770078. S2CID 7017701.

- Sahoo, S.; Singh, A.; Himabindu, G.; Banerjee, J.; Sitalaximi, T.; Gaikwad, S.; Trivedi, R.; Endicott, P.; Kivisild, T.; Metspalu, M.; Villems, R.; Kashyap, V. K. (2006). "A prehistory of Indian Y chromosomes: Evaluating demic diffusion scenarios". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 103 (4): 843–8. Bibcode:2006PNAS..103..843S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0507714103. PMC 1347984. PMID 16415161.

- Sanchez, J. J.; Hallenberg, C.; Børsting, C.; Hernandez, A.; Gorlin, R. J. (2005). "High frequencies of Y chromosome lineages characterized by E3b1, DYS19-11, DYS392-12 in Somali males". European Journal of Human Genetics. 13 (7): 856–66. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201390. PMID 15756297.

- Scozzari, R.; Cruciani, F.; Pangrazio, A.; Santolamazza, P.; Vona, G.; Moral, P.; Latini, V.; Varesi, L.; Memmi, M. M.; Romano, V.; De Leo, G.; Gennarelli, M.; Jaruzelska, J.; Villems, R.; Parik, J.; MacAulay, V.; Torroni, A. (2001). "Human Y-chromosome variation in the Western Mediterranean area: Implications for the peopling of the region". Human Immunology. 62 (9): 871–84. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.408.4857. doi:10.1016/S0198-8859(01)00286-5. PMID 11543889.

- Semino, O.; Passarino, G.; Oefner, P. J.; Lin, A. A.; Arbuzova, S.; Beckman, L. E.; De Benedictis, G.; Francalacci, P.; Kouvatsi, A.; Limborska, S.; Marcikiae, M.; Mika, A.; Mika, B.; Primorac, D.; Santachiara-Benerecetti, A. S.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Underhill, P. A. (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective". Science. 290 (5494): 1155–59. Bibcode:2000Sci...290.1155S. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

- Sengupta, S.; Zhivotovsky, L. A.; King, R.; Mehdi, S. Q.; Edmonds, C. A.; Chow, C-E. T.; Lin, A. A.; Mitra, M.; Sil, S. K.; Ramesh, A.; Usha Rani, M. V.; Thakur, C. M.; Cavalli-Sforza, L. L.; Majumder, P. P.; Underhill, P. A. (2006). "Polarity and Temporality of High-Resolution Y-Chromosome Distributions in India Identify Both Indigenous and Exogenous Expansions and Reveal Minor Genetic Influence of Central Asian Pastoralists". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 78 (2): 202–21. doi:10.1086/499411. PMC 1380230. PMID 16400607.

- Shah, A. M.; Tamang, R.; Moorjani, P.; Rani, D. S.; Govindaraj, P.; Kulkarni, G.; Bhattacharya, T.; Mustak, M. S.; Bhaskar, L. V. K. S.; Reddy, A. G.; Gadhvi, D.; Gai, P. B.; Chaubey, G.; Patterson, N.; Reich, D.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Singh, L.; Thangaraj, K. (2011). "Indian Siddis: African Descendants with Indian Admixture". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (1): 154–61. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.030. PMC 3135801. PMID 21741027.

- Tarkhnishvili D, Gavashelishvili A, Murtskhvaladze M, Gabelaia M, Tevzadze G (2014). "Human paternal lineages, languages, and environment in the Caucasus". Human Biology. 86 (2): 113–30. doi:10.3378/027.086.0205. PMID 25397702. S2CID 7733899.

- Thamseem, I.; Thangaraj, K.; Chaubey, G.; Singh, V.; Bhaskar, L. V. K. S.; Reddy, B. M.; Reddy, A. G.; Singh, L. (2006). "Genetic affinities among the lower castes and tribal groups of India: Inference from Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA". BMC Genetics. 7: 42. doi:10.1186/1471-2156-7-42. PMC 1569435. PMID 16893451.

- Thomas, M. G.; Barnes, I.; Weale, M. E.; Jones, A. L.; Forster, P.; Bradman, N.; Pramstaller, Peter P (2008). "New genetic evidence supports isolation and drift in the Ladin communities of the South Tyrolean Alps but not an ancient origin in the Middle East". European Journal of Human Genetics. 16 (1): 124–34. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201906. PMID 17712356.

- Weale, M.; Yepiskoposyan, L.; Jager, R.; Hovhannisyan, N.; Khudoyan, A.; Burbage-Hall, O.; Bradman, N.; Thomas, M. (2001). "Armenian Y chromosome haplotypes reveal strong regional structure within a single ethno-national group". Human Genetics. 109 (6): 659–74. doi:10.1007/s00439-001-0627-9. PMID 11810279. S2CID 23113666.

- Wells, R. S.; Yuldasheva, N.; Ruzibakiev, R.; Underhill, P. A.; Evseeva, I.; Blue-Smith, J.; Jin, L.; Su, B.; Pitchappan, R.; Shanmugalakshmi, S.; Balakrishnan, K.; Read, M.; Pearson, N. M.; Zerjal, T.; Webster, M. T.; Zholoshvili, I.; Jamarjashvili, E.; Gambarov, S.; Nikbin, B.; Dostiev, A.; Aknazarov, O.; Zalloua, P.; Tsoy, I.; Kitaev, M.; Mirrakhimov, M.; Chariev, A.; Bodmer, W. F. (2001). "The Eurasian Heartland: A continental perspective on Y-chromosome diversity". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (18): 10244–49. Bibcode:2001PNAS...9810244W. doi:10.1073/pnas.171305098. PMC 56946. PMID 11526236.

- Young, K. L.; Sun, G.; Deka, R.; Crawford, M. H. (2011). "Paternal Genetic History of the Basque Population of Spain" (PDF). Human Biology. 83 (4): 455–75. doi:10.3378/027.083.0402. hdl:1808/16387. PMID 21846204. S2CID 3191418.

- Zalloua, P. A.; Xue, Y.; Khalife, J.; Makhoul, N.; Debiane, L.; Platt, D. E.; Royyuru, A. K.; Herrera, R. J.; Hernanz, D. F. S.; Blue-Smith, J.; Wells, R. S.; Comas, D.; Bertranpetit, J.; Tyler-Smith, C.; Genographic Consortium (2008). "Y-Chromosomal Diversity in Lebanon is Structured by Recent Historical Events". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (4): 873–82. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.020. PMC 2427286. PMID 18374297.

Web-sources

- Krahn, T.; FTDNA. "FTDNA Draft Y-DNA Tree (AKA YTree)". Family Tree DNA. Archived from the original on 2015-08-15. Retrieved 2013-01-01.

- Henson, G.; Hrechdakian, P.; FTDNA (2013). "L – The Y-Haplogroup L Project". Retrieved 2013-01-01.

Sources for conversion tables

- Capelli, Cristian; Wilson, James F.; Richards, Martin; Stumpf, Michael P.H.; et al. (February 2001). "A Predominantly Indigenous Paternal Heritage for the Austronesian-Speaking Peoples of Insular Southeast Asia and Oceania". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 68 (2): 432–443. doi:10.1086/318205. PMC 1235276. PMID 11170891.

- Hammer, Michael F.; Karafet, Tatiana M.; Redd, Alan J.; Jarjanazi, Hamdi; et al. (1 July 2001). "Hierarchical Patterns of Global Human Y-Chromosome Diversity". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 18 (7): 1189–1203. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003906. PMID 11420360.

- Jobling, Mark A.; Tyler-Smith, Chris (2000), "New uses for new haplotypes", Trends in Genetics, 16 (8): 356–62, doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(00)02057-6, PMID 10904265

- Kaladjieva, Luba; Calafell, Francesc; Jobling, Mark A; Angelicheva, Dora; et al. (February 2001). "Patterns of inter- and intra-group genetic diversity in the Vlax Roma as revealed by Y chromosome and mitochondrial DNA lineages". European Journal of Human Genetics. 9 (2): 97–104. doi:10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200597. PMID 11313742. S2CID 21432405.

- Karafet, Tatiana; Xu, Liping; Du, Ruofu; Wang, William; et al. (September 2001). "Paternal Population History of East Asia: Sources, Patterns, and Microevolutionary Processes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 69 (3): 615–628. doi:10.1086/323299. PMC 1235490. PMID 11481588.

- Karafet, T. M.; Mendez, F. L.; Meilerman, M. B.; Underhill, P. A.; Zegura, S. L.; Hammer, M. F. (2008), "New binary polymorphisms reshape and increase resolution of the human Y chromosomal haplogroup tree", Genome Research, 18 (5): 830–8, doi:10.1101/gr.7172008, PMC 2336805, PMID 18385274

- Su, Bing; Xiao, Junhua; Underhill, Peter; Deka, Ranjan; et al. (December 1999). "Y-Chromosome Evidence for a Northward Migration of Modern Humans into Eastern Asia during the Last Ice Age". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 65 (6): 1718–1724. doi:10.1086/302680. PMC 1288383. PMID 10577926.

- Underhill, Peter A.; Shen, Peidong; Lin, Alice A.; Jin, Li; et al. (November 2000). "Y chromosome sequence variation and the history of human populations". Nature Genetics. 26 (3): 358–361. doi:10.1038/81685. PMID 11062480. S2CID 12893406.

- Yunusbaev, Bayazit Bulatovich (2006). ПОПУЛЯЦИОННО-ГЕНЕТИЧЕСКОЕ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЕ НАРОДОВ ДАГЕСТАНА ПО ДАННЫМ О ПОЛИМОРФИЗМЕ У-ХРОМОСОМЫ И АТД-ИНСЕРЦИЙ [Population-genetic study of the peoples of Dagestan on the data on Y-chromosome and ATD-insertion polymorphism] (PDF) (PhD). Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 February 2007.

- Zhong, H.; Shi, H.; Qi, X.-B.; Duan, Z.-Y.; Tan, P.-P.; Jin, L.; Su, B.; Ma, R. Z. (1 January 2011). "Extended Y Chromosome Investigation Suggests Postglacial Migrations of Modern Humans into East Asia via the Northern Route". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 717–727. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq247. PMID 20837606.

External links

- ISOGG,

- Genebase (2006). "Genebase Tutorials: Learn about Y-chromosome Haplogroup L". Archived from the original on 2012-10-23.

- Spread of Haplogroup L, from National Geographic

- The India Genealogical Project

- Y Haplogroup L