Hasselt dialect

Hasselt dialect or Hasselt Limburgish (natively (H)essels,[2] Standard Dutch: Hasselts [ˈɦɑsəlts]) is the city dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Belgian city of Hasselt alongside the Dutch language. All of its speakers are bilingual with standard Dutch.[1]

| Hasselt dialect | |

|---|---|

| (H)essels | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɦæsəls] |

| Native to | Belgium |

| Region | Hasselt |

Indo-European

| |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

Phonology

Consonants

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | ||||

| Plosive / affricate |

voiceless | p | t | tʃ | k | ||

| voiced | b | d | dʒ | ||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | ||

| voiced | v | z | ɣ | ɦ | |||

| Liquid | l | ʀ | |||||

| Approximant | β | j | |||||

- Obstruents are devoiced word-finally. However, when the next word starts with a vowel and is pronounced without a pause, both voiced and voiceless word-final obstruents are realized as voiced.[4]

- /m, p, b, β/ are bilabial, whereas /f, v/ are labiodental.[1]

- In the palatal sequences /ntʃ, ndʒ/, the affricates tend to be realized as palatalized stops. Affricates are used in other positions and, in the case of conservative speakers, also in /ntʃ, ndʒ/.[4]

- /ɦ/ is often dropped,[4] though this is not marked in transcriptions in this article.

Realization of /ʀ/

According to Peters (2006), /ʀ/ is realized as a voiced trill, either uvular [ʀ] or alveolar [r]. Between vowels, it is sometimes realized with one contact (i.e. as a tap) [ʀ̆ ~ ɾ],[4] whereas word-finally, it can be devoiced to [ʀ̥ ~ r̥].[5]

According to Sebregts (2014), about two thirds of speakers have a uvular /ʀ/, whereas about one third has a categorical alveolar /ʀ/. There are also a few speakers who mix uvular and alveolar articulations.[6]

Among uvular articulations, he lists uvular trill [ʀ], uvular fricative trill [ʀ̝], uvular fricative [ʁ] and uvular approximant [ʁ̞], which are used more or less equally often in all contexts. Almost all speakers with a uvular /ʀ/ use all four of these realizations.[7]

Among alveolar articulations, he lists alveolar tap [ɾ], voiced alveolar fricative [ɹ̝], alveolar approximant [ɹ], voiceless alveolar trill [r̥], alveolar tapped or trilled fricative [ɾ̞ ~ r̝], voiceless alveolar tap [ɾ̥] and voiceless alveolar fricative [ɹ̝̊]. Among these, the tap is most common, whereas the tapped/trilled fricative is the second most common realization.[7]

Elsewhere in the article, the consonant is transcribed ⟨ʀ⟩ for the sake of consistency with IPA transcriptions of other dialects of Limburgish.

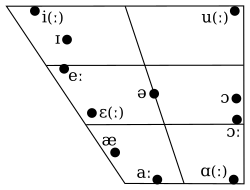

Vowels

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- The Hasselt dialect has undergone both the Old Saxon monophthongization (which has turned the older eik and boum into eek and boom) and the monophthongization of the former /ɛi/ and /œy/ to /ɛː/ and /œː/ (which was then mostly merged with /ɛː/ due to the unrounding described below).

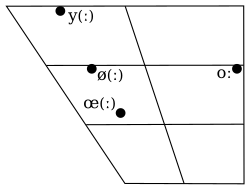

- Among the marginal vowels, the nasal ones occur only in French loanwords (note that /æ̃ː/ is typically transcribed with ⟨ɛ̃⟩ in transcriptions of French and that /œ̃ː/ is very rare, as in Standard Dutch), whereas /oː/ is restricted to loanwords from standard Dutch and English. As in about 50 other dialects spoken in Belgian Limburg, the rounded front vowels /y, yː, ø, øː, œ, œː/ have largely been replaced with their unrounded counterparts /i, iː, ɪ, eː, ɛ, ɛː/ and are mostly restricted to loanwords from French. The marginal diphthong /ai/ occurs only in loanwords from French and interjections. /øi/ is also rare, and like /ai/ occurs only in the word-final position.[9][10]

- Phonetically, /aː/ is near-front [a̠ː].[10]

- All of the back vowels are almost fully back.[8] Among these, /u, uː, ɔ, ɔː/ and the non-native /oː/ are rounded, whereas /ɑ, ɑː/ are unrounded.

- Before alveolar consonants, the long monophthongs /uː, øː, œː/ and the diphthongs /ei, ou/ are realized as centering diphthongs [uə, øə, œə, eə, oə]. In the case of /ei/, this happens only before sonorants, with the disyllabic [ei.ə] being an alternative pronunciation. Thus, noêd /ˈnuːt/ 'distress', meud /ˈmøːt/ 'fashion', näöts /ˈnœːts/ 'news', keejl /ˈkeil/ 'cool' and moowd /ˈmout/ 'tired' surface as [ˈnuət], [ˈmøət], [ˈnœəts], [ˈkeəl ~ ˈkei.əl] and [ˈmoət]. The distinction between a long monophthong and a centering diphthong is only phonemic in the case of the /iː–iə/ pair, as exemplified by the minimal pair briêd /ˈbʀiːt˨/ 'broad' vs. brieëd /ˈbʀiət˨/ 'plank'.[10]

- /ə, ɔ/ are mid [ə, ɔ̝].[10]

- /ə/ occurs only in unstressed syllables.[4]

- /æ/ is near-open, whereas /aː, ɑ, ɑː/ are open.[10]

- /ui/ and /ɔi/ have somewhat advanced first elements ([u̟] and [ɔ̟], respectively). The latter diphthong occurs only in the word-final position.[10]

- Among the closing-fronting diphthongs, the ending points of /ɔi/ and /ai/ tend to be closer to [e̠] than [i]; in addition, the first element of /ai/ is closer to [ɐ]: [ɔ̟e̠, ɐe̠].[10]

Three long monophthongs can occur before coda /j/ - those are /uː/, /ɔː/ and /ɑː/, with the latter two occurring only before a word-final /j/, as in kaoj /ˈkɔːj/ 'harm' (pl.) and lâj /ˈlɑːj/ 'drawer'. An example word for the sequence /uːj/ is noêj /ˈnuːj/ 'unwillingly'.[10]

Stress and tone

The location of stress is the same as in Belgian Standard Dutch. In compound nouns, the stress is sometimes shifted to the second element (the head noun), as in stadhäös /stɑtˈɦœːs/ 'town hall'. Loanwords from French sometimes preserve the original final stress.[11]

As many other Limburgish dialects, the Hasselt dialect features a phonemic pitch accent, a distinction between the 'push tone' (stoottoon) and the 'dragging tone' (sleeptoon). It can be assumed that the latter is a lexical low tone, whereas the former is lexically toneless. Examples of words differing only by pitch accent include hin /ˈɦɪn/ 'hen' vs. hin /ˈɦɪn˨/ 'them' as well as berreg /ˈbæʀx/ 'mountains' vs. berreg /ˈbæʀx˨/ 'mountain'.[12] Phonetically, the push tone rises then falls ([ˈɦɪn˧˦˧], [ˈbæʀ˧˦˧əx]), whereas the dragging tone falls, then rises, then falls again ([ˈɦɪn˥˩˩˥˥˩], [ˈbæʀ˥˩˩˥˥˩əx]). This phonetic realization of pitch accent is called Rule 0 by Björn Köhnlein.[13] Elsewhere in the article, the broad transcription ⟨ˈɦɪn, ˈbæʀəx, ˈɦɪn˨, ˈbæʀ˨əx⟩ is used even in phonetic transcription.

A unique feature of this dialect is that all stressed syllables can bear either of the accents, even the CVC syllables with a non-sonorant coda. In compounds, all combinations of pitch accent are possible: Aastraot /ˈaːˌstʀɔːt/ 'Old Street', Vèsmerrek /ˈvɛsˌmæʀk˨/ 'Fish Market', Ekestraot /ˈeː˨kəˌstʀɔːt/ 'Oak Street' and Freetmerrek /ˈfʀeːt˨ˌmæʀk˨/ 'Fruit Market'.[14]

Sample

The sample text is a reading of the first sentence of The North Wind and the Sun.

- "The north wind and the sun were discussing which of the two of them was the strongest. Just then someone came past who had a thick, warm, winter coat on."

Phonetic transcription:

- [də ˈnɔːʀdəʀˌβɛntʃ˨ ən də ˈzɔn | βøːʀən ɑn dɪskəˈtɛːʀə | ˈeː˨vəʀ ˈβiə vɔn ɪn ˈtβɛː ət ˈstæʀ˨əkstə βøːʀ || ˈtuːn ˈkum təʀ ˈdʒys ˈei˨mɑnt vʀ̩ˈbɛː˨ | ˈdiː nən ˈdɪkə ˈβæʀmə ˈjɑs ˈɑːn˨ɦaː][15]

Orthographic version:

- De naorderwèndj en de zon weuren an disketaere ever wieë von hin twae het sterrekste weur, toên koem ter dzjuus eejmand verbae diê nen dikke, werme jas ânhaa.

References

- Peters (2006), p. 117.

- Staelens (1989).

- Sebregts (2014), pp. 96–97.

- Peters (2006), p. 118.

- Peters (2006). While the author does not state that explicitly, he uses the symbol ⟨r̥⟩ for many instances of the word-final /ʀ/.

- Sebregts (2014), p. 96.

- Sebregts (2014), p. 97.

- Peters (2006), pp. 118–119.

- Belemans & Keulen (2004), p. 34.

- Peters (2006), p. 119.

- Peters (2006), pp. 119–120.

- Peters (2006), pp. 120–121.

- Köhnlein (2013), pp. 5–7.

- Peters (2006), p. 120.

- Peters (2006), p. 123.

Bibliography

- Belemans, Rob; Keulen, Ronny (2004), Belgisch-Limburgs, Lannoo Uitgeverij, ISBN 978-9020958553

- Köhnlein, Björn (2013), "Optimizing the relation between tone and prominence: Evidence from Franconian, Scandinavian, and Serbo-Croatian tone accent systems" (PDF), Lingua, 131: 1–28, doi:10.1016/j.lingua.2013.03.002

- Peters, Jörg (2006), "The dialect of Hasselt", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (1): 117–124, doi:10.1017/S0025100306002428

- Sebregts, Koen (2014), "3.4.4 Hasselt" (PDF), The Sociophonetics and Phonology of Dutch r, Utrecht: LOT, pp. 96–99, ISBN 978-94-6093-161-1

- Staelens, Xavier (1989), Dieksjenèèr van 't (H)essels (3rd ed.), Hasselt: de Langeman

Further reading

- Grootaers, Ludovic; Grauls, Jan (1930), Klankleer van het Hasseltsch dialect, Leuven: de Vlaamsche Drukkerij

- Peters, Jörg (2008), "Tone and intonation in the dialect of Hasselt", Linguistics, 46 (5): 983–1018, doi:10.1515/LING.2008.032, hdl:2066/68267, S2CID 3302630