History of Alagoas

The history from the Brazilian state of Alagoas begins before the discovery of Brazil by the Portuguese, when the territory was inhabited by the Caeté people.[1] The coast of the current state of Alagoas, recognized since the first Portuguese expeditions, was also visited early on by vessels of other nationalities for the barter of brazilwood (Caesalpinia echinata).[2]

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Brazil |

|---|

|

|

|

Within the Captaincies of Brazil system (1534), the territory was part of the captaincy of Pernambuco, and its occupation dates back to the foundation of the village of Penedo (1545), on the banks of the São Francisco River, by the donee Duarte Coelho Pereira, who encouraged the construction of sugar cane mills in the region. The area was also the location of the shipwreck of the Our Lady of Perpetual Help and subsequent massacre of the survivors, among them Bishop Dom Pero Fernandes Sardinha, by the Caeté people (1556), an episode that served as motivation for the war of extermination waged against this indigenous group by the Portuguese Crown. At the beginning of the XVII century, besides sugarcane plantation, the region of Alagoas was an expressive regional producer of manioc flour, tobacco, cattle and dried fish, consumed in the captaincy of Pernambuco. During the Dutch invasions of Brazil (1630-1654), its coastline became the scenario of violent combats, while the quilombos, formed by Africans escaped from the sugar cane mills in Pernambuco and Bahia, multiplied in the highlands of its countryside. Palmares, the most famous one, reached a population of twenty thousand at its peak. The territory became the Comarca of Alagoas in 1711 and was dismembered from the Captaincy of Pernambuco (decree signed by the King of Portugal, João VI, on September 16, 1817), given the importance of Alagoas to the Portuguese Court. Its first governor, Sebastião Francisco de Melo e Póvoas, took office on January 22, 1819.[2]

During the Empire of Brazil (1822-1889), Alagoas suffered the consequences of movements such as the Confederation of the Equator (1824) and Cabanagem (1835-1840). The Provincial Law of December 9, 1839 transferred the capital of the Province from the City of Alagoas (today Marechal Deodoro, but it was once called Vila Madalena de Subaúma), to the village of Maceió, then elevated to a city.[2]

The first Constitution of the State was signed on June 11, 1891, amidst serious political agitations that marked the beginning of republican life. The first two presidents of the Republic of Brazil, Deodoro da Fonseca and Floriano Peixoto, were from Alagoas[2] and received tributes by having their names linked to the cities of Marechal Deodoro, in Alagoas (homage to Marechal Deodoro da Fonseca) and Florianópolis, in Santa Catarina (homage to Marechal Floriano Peixoto).

First inhabitants

Before the arrival of the Portuguese, the coast of the current state of Alagoas was invaded by Tupi-speaking people from the Amazon. They expelled the former inhabitants, speakers of languages from the macro-jê linguistic trunk, to the inland of the continent. In the 16th century, when the first Europeans arrived on the coast of Alagoas, it was inhabited by the Tupi nation of Caetés.[3]

Arrival of Europeans

Barra Grande must have been the first point in the territory of Alagoas visited by the Portuguese explorers, on the occasion of Américo Vespúcio's journey, in 1501.[4] Although there is no reference to that port, excellent for the reception of ships coming from the north to the south, it is believed to have been the first contact with the land of Alagoas. On September 29, Vespúcio sighted a river that he called São Miguel;[5] on October 4, he renamed the newly discovered river São Francisco, which today borders Sergipe and Alagoas.[6]

In the following decades, the French walked along the Alagoas coast, trafficking brazilwood with the surrounding natives. Until today, the French port documents the presence of those people there.[7]

Duarte Coelho, first donee of the captaincy of Pernambuco,[5] made an expedition to the south; there are no documents to prove it, but there is evidence that it took place in 1545 and that it resulted in the foundation of Penedo, a city on the banks of the São Francisco river with a valuable artistic and cultural heritage that was the scenario of important events in Colonial Brazil.[8]

In 1556, the bishop Dom Pero Fernandes Sardinha was returning to Portugal from Bahia when his ship sank in front of the inlet located in the current city of Coruripe. Sardinha was killed and devoured by the Caeté people, one of the numerous indigenous tribes that existed in the region.[9] Popular belief states that the divine wrath dried up and sterilized all the soil stained by Sardinha's blood. To avenge him, Jerônimo de Albuquerque commanded a war expedition against the Caetés, destroying them almost completely[5] and enslaving the survivors.[3]

In 1570, a second expedition sent by Duarte Coelho and commanded by Cristóvão Lins explored the north of Alagoas, where they founded Porto Calvo and five sugar cane mills, of which two remain, Buenos Aires and Escurial.[10] In the latter, in 1601, the English corsair Anthony Knivet, who had traveled overland after escaping from Bahia, where he had been a prisoner of the Portuguese, landed.[5]

The Dutch War

In the beginning of the 17th century, Penedo, Porto Calvo and Alagoas were already parishes;[11] however, they became villages in 1636.[11] Due to its regional economy dependence on the sugar activity, sugar cane mills became the main centers of land occupation.[5] From 1630 on, Alagoas, hit by the Dutch invasion,[1] had its villages, churches and mills burned and pillaged.[5]

The Portuguese reacted harshly.[5] Beaten by successive setbacks, the Dutch weakened and thought about retreating, when the mamluk Domingos Fernandes Calabar arrived from Porto Calvo and joined them.[12] He, being a great expert of the area, guided the Dutch in a new expedition to Alagoas.[12] The invaders docked in Barra Grande, from where they went to various locations, always with great success.[5] In Santa Luzia do Norte, the population, forewarned, offered resistance and, [13]after a fierce battle, the Dutch retreated and returned to Recife. However, they achieved several victories in places such as the arraial of Bom Jesus, between Recife and Olinda.[5]

Alagoas, Penedo and Porto Calvo: these are the main places where the battles took place in Alagoas' lands.[5] Eventually, the Portuguese reclaimed Porto Calvo and captured Calabar, who died on the gallows in 1635.[12] Clara Camarão, a native of Porto Calvo, also distinguished herself in the fight against the Dutch.[14] She accompanied her husband, the indigenous soldier Filipe Camarão, in almost every battle, and recruited other women to lead them.

War of Palmares

Around 1641, a Dutch leader affirmed that the region of Alagoas was almost depopulated;[15] Maurice of Nassau thought of repopulating it,[15] but the project did not succeed. At that time, tobacco was also produced in Alagoas, and the one from Barra Grande was considered of excellent quality.[5] In 1645, the population participated in the nationalist movement, joining the fight under the command of Cristóvão Lins, grandson and namesake of the first settler of Porto Calvo. Once the Dutch were expelled from the territory of Alagoas, in September 1645,[16] the population continued its fight against them, but now in Pernambuco territory.[5]

At the end of the 17th century, the struggles against the black quilombos gathered in Palmares intensified.[17] Two years later, after Domingos Jorge Velho's first attempts were frustrated, especially in 1692,[18] the quilombo was defeated,[19] with the simultaneous attack of three columns: one of Domingos Jorge, from São Paulo; another under the command of Bernardo Vieira de Melo, from Pernambuco; and the third, commanded by Sebastião Dias, formed by people from Alagoas.[5] Palmares had begun to establish at the end of the 16th century, and resisted successive attacks for almost a century.[20]

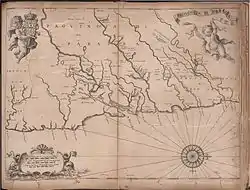

Palmares, one of the largest strongholds of fugitive slaves in colonial Brazil,[21] initially occupied the wide area that stretched from the Cabo de Santo Agostinho to the São Francisco River, covered with palm trees. The area of the quilombo, progressively reduced over time, would be concentrated, by the end of the 17th century, in the still extensive region delimited by the villages of Una and Sirinhaém, in Pernambuco, and Porto Calvo, Alagoas and São Francisco (now Penedo), in Alagoas. The slaves had organized a true African-style state in the redoubt, with the quilombo consisting of at least 11 different settlements (mocambos) governed by oligarchs under the supreme leadership of King Ganga-Zumba. From 1667 on, there was an increase in the number of raids against the black people, first to recapture them, then to conquer the land they had seized.[20] The attacks by sergeant-general Manuel Lopes (1675) and Fernão Carrilho (1677)[22] were disastrous for the quilombolas, who were forced to accept peace under unfavorable conditions. Despite this setback, the fight would continue, led by Zumbi, Ganga-Zumba's nephew, against whose fierce hosts. After a first punitive expedition, in 1679,[5] and several entries without major consequences, the bandeirante from São Paulo, Domingos Jorge Velho, hired by the governor of Pernambuco, João da Cunha Souto Maior, would finally return.[23] In the first months of 1694, Domingos Jorge Velho managed to destroy the quilombo, with the help of troops from Alagoas and Pernambuco, commanded by Sebastião Dias and Bernardo Vieira de Melo, respectively.[24] Zumbi would manage to escape, gathering new combatants, but, betrayed, would find himself surrounded by enemy forces, with about twenty of his men dying in battle, on November 20, 1695.[25] After more than sixty years, the quilombo of Palmares, "the greatest protest against despotism that an unfortunate race has ever traced on the face of the world," would disappear, in the words of Craveiro Costa.[5]

Creation of the comarca

Alagoas was already showing signs of prosperity and development, both economically and culturally. Its main product was sugar, but manioc, tobacco and corn were also cultivated, although to a lesser extent; leathers, skins and brazilwood were exported. The abundant forests provided wood for the construction of ships. In the convents of Penedo and Alagoas (now Marechal Deodoro), the Franciscans held courses and published sermons and poetry.[5] All this was used to justify the royal act of October 9, 1710, which created the Comarca of Alagoas,[26] installed in 1711.[27] From then on, the judicial organization restricted the feudal authority of the lords, and even of the representatives of the metropolis; the comarca was being developed.[5] In 1730, the governor of Pernambuco, proposing the extinction of the decadent captaincy of Paraíba to the king, highlighted the prosperity of Alagoas, with its almost fifty sugar cane mills, ten parishes, and appreciable income for the royal treasury.[28] Besides sugar, the cultivation of cotton increased, which was introduced in the 1770s; in 1778, samples of woven cotton from Alagoas were already being exported to Lisbon.[5] In Penedo and Porto Calvo, common fabric was manufactured for the use of slaves. In 1754, Friar João de Santa Angela published, in Lisbon, his book of sermons and poetry; it was the first work by a man from Alagoas.[29] The population was growing, distributing itself in various activities. A demographic calculation, ordered to be made in 1816 by the public prosecutor Antônio Ferreira Batalha, registered a population of 89,589 people.[5]

Independent Captaincy

Alagoas became a judicial district in 1711 and officially separated from Pernambuco in 1817 to become an independent captaincy, by decree signed by the King of Portugal, Dom João VI.[30] This separation happened due to the importance of Alagoas to the Portuguese Court. For Dom João VI, establishing a political base in Alagoas was very important for the kingdom of Portugal, since it was a rich district. From the economic point of view, Alagoas had a sugar cane culture, large landholdings, and strategically bordered Bahia and Pernambuco (where the republican movement that assumed power in Pernambuco, betraying the crown, was bursting).

The mediator Batalha was the main mentor of the people of Alagoas, dismembering the comarca from the jurisdiction of Pernambuco and setting up a provisional government there. These acts, added to the importance of Alagoas for the Kingdom of Portugal, were enough to open paths that led the King D. João to sanction the dismemberment.[5] Sebastião Francisco de Melo e Póvoas, appointed governor, only took office on January 22, 1819.[31] That year, a new census showed a population of 111,973 people distributed in eight villages.[5]

The outbreak of prosperity in Alagoas was accentuated after 1817.[5] On August 17, 1831 appeared the Íris Alagoense, the first newspaper published in the province.[32] However, the first years of independence were not easy. A sequence of movements shook provincial life: in 1824, the Confederation of the Equator; in 1832-1835, the Cabanada; in 1844, the rebellion known as Lisos e Cabeludos; in 1849, the repercussions of the Beach rebellion.[5]

Many books mistakenly tell the story of the political independence of Alagoas, which is always narrated from the point of view of historians from Pernambuco, where Alagoas appears as a passive subject, fruit of Pernambuco's heroism. The emancipation is seen as a prize to the Alagoas inhabitants for not having joined the Pernambucan revolt of 1817, also known as the Revolt of the Fathers, which had an influence on the separation of the district of Alagoas from the district of Pernambuco.

Relocation of the capital

In 1839 the capital, located in the old city of Alagoas (now Marechal Deodoro), was transferred to the village of Maceió, situated on the coast, on the road between the north, center and south of the province.[33] In the transfer process, the two most important political factions clashed, one headed by the later Viscount Sinimbu, and the other by Judge Tavares Bastos,[5] father of the future philosopher Tavares Bastos, born in the same year.[34] At that time the province had eight villages and the provincial assembly had been functioning since 1835.[5]

The government of the province was succeeded by presidents appointed by the emperor, not always interested in the destiny of the land, and at other times involved in partisan fights. The province, however, was progressing.[5] In the economic field, it is worth mentioning the foundation, in 1857, of the first fabric factory in Alagoas, the Companhia União Mercantil, in the Fernão Velho neighborhood,[35] idealized by the baron of Jaraguá, contributing to the development of the regional economy.[5] Thirty years later, on October 15, 1888, the Companhia Alagoana de Fiação e Tecidos was inaugurated in Rio Largo.[36] On September 30, 1892, the Companhia Progresso Alagoano was founded in Cachoeira.[35] Then, in 1924, the Companhia de Fiação e Tecidos Norte-Alagoas, the "Health Factory", was founded.[37] Out of this textile activity emerged, with great national prestige, the towels of Companhia Alagoana. Education received an incentive with the establishment of the Liceu Alagoano, in 1849, destined for the high school level; today it is known as the State College of Alagoas.[5] Primary education, already benefited in 1864 by the establishment of a Normal School which today operates under the name of Institute of Education, received a significant boost with the creation of new schools. The historical and geographical studies were developed[5] due to the foundation, in 1869, of the Archaeologic and Geographic Institute of Alagoas, today the Historic and Geographic Institute of Alagoas.[38] From the end of the empire to the beginning of the republic, the movement for the construction of central mills and the technical improvement of sugar production increased, which would give place to the refineries, with the first one founded, however, already in the republican period.[5]

The abolitionist and republican movements of the last years of the monarchy would reach the province; the first one through the Sociedade Libertadora Alagoana[5] and the Gutenberg and Lincoln newspapers.[39] The abolitionist campaign mobilized the intellectuals of Alagoas, without, however, reaching the excesses of violence. Teachers and journalists attracted the youth to the campaign, and after the abolition, in 1888, it was a teacher like Francisco Domingues da Silva who took the initiative to create a professional education institute for the children of former slaves.[5]

Republic

.jpg.webp)

The republican movement, intensified by the abolition, was reflected in the activities of the press and propaganda clubs. Among them were the Centro Republicano Federalista, the oldest and most important, the Clube Federal Republicano and the Clube Centro Popular Republicano Maceioense; the latter two existing in the capital of the state at the time of the proclamation. In the countryside there were also other propaganda clubs. The Gutenberg was the most vehement press organ in spreading the republican idea.[5]

On the same day that the republic was proclaimed in Rio de Janeiro, Pedro Ribeiro Moreira, the last delegate of the imperial government for the province, assumed the presidency in Maceió. A governing board was organized as soon as the change of regime was confirmed. However, on November 19, Marshal Deodoro designated his brother, Pedro Paulino da Fonseca, to govern the new state.[5] He was also the first governor elected after the promulgation of the state constitution on June 12, 1891.[40]

The first ten years of republican life in the province were turbulent and uncertain. Governments succeeded each other, nominated by the central power or elected by the people, but almost always replaced or deposed. Several governing boards have been formed at one time or another.[5] The situation was consolidated in the early years of the 20th century, with the administrations of the baron of Traipu and of Euclides Malta, the first of the so-called "Malta oligarchy", which lasted until 1912.[1] Euclides governed from 1900 to 1903 and was succeeded by his brother, Joaquim Paulo, from 1903 to 1906; Euclides returned to power from 1906 to 1909, was reelected that year and remained in power for another three-year term, until 1912.[5]

The first 12 years of the century were marked by partisan fights. However, there was no interruption in the different activities of the state. In the architectural context, Maceió gained numerous public buildings, such as the government palace, inaugurated on September 16, 1902, the Teatro Deodoro and the municipality building, still standing today. Due to Alfredo Rego's pedagogical activity, a teaching reform was carried out, updating the previous one, dated from the end of the empire, guided by Manuel Baltasar Pereira Diegues Júnior, creator of the Teachers Institute, later called Pedagogium, a pioneering initiative at the time. A new remodeling of teaching took place in 1912-1914, under Manuel's guidance, and the first school group was created.[5]

In 1912, the Democratic Party managed to defeat the Malta oligarchy after an intense campaign, in which fierce street battles were registered, including the death of poet Bráulio Cavalcanti in a public square while participating in a democratic rally. Clodoaldo da Fonseca, governor-elect, although not from Alagoas, was connected to the state through his family: he was Deodoro's nephew, Pedro Paulino's son, and a relative of Marshal Hermes da Fonseca, president of the republic at the time.[5]

The struggles against the Malta family also involved Afro-Brazilian cult groups. According to the opposition newspapers, the shango and candomblé groups had the governor Malta as a stimulator.[5] Portraits of the opposition Democratic leaders were found among prayer papers and cloths with drawn symbols of Ogun, Ifá and Eshu. The group that supported the governor was called Leba, a reference to one of the figures of the shango orisha. The collection confiscated by the police was preserved - pieces, objects, insignias and symbols of the cult are kept in the museum of the Historic Institute as one of the most precious collections of the Afro-Brazilian cult.[5]

In 1924, the current second largest city in Alagoas, the city of Arapiraca, becomes independent, with the territory located in the exact center of Alagoas.

Until 1930, the Democratic Party maintained the situation through the governors who succeeded Clodoaldo. Each of them made a contribution to the progress of the state. Roads were opened towards the north and the center, and later the stretch between Atalaia and Palmeira dos Índios, a penetration road to the sertanejo zone; school groups were built in almost all the cities; Maceió was renewed with the opening of streets and avenues; criminality was fought, especially with the movement against banditry, which culminated, in 1938, with the extermination of the gang of Lampião; petroleum research was promoted. The political successions were practically without a fight, as the single candidate from the Democratic Party almost always predominated.[5]

Upon the victory of the Revolution of 1930, also without an armed struggle in the state, the interventor system began (with a brief interruption between 1935 and 1937), and lasted until 1947, when the re-democratization of the country led to the promulgation of a new constitution for the state. The period of interventories, as it was called, was equally productive, despite the lack of continuity in the administrations, almost always for short periods. During this period, among other notable facts, were the research work on oil;[5] the construction of the port of Maceió, inaugurated in 1940;[41] the increase in economic activities, especially with the diversification of agricultural production and the implementation of the dairy industry in Jacaré dos Homens, setting up the dairy cooperative for the production of milk, butter and cheese; the increase in rural education and the expansion of cooperatives. Such development allowed that, in the period of the World War II, Alagoas contributed, in an effective way, to the supply of neighboring states, without harming its collaboration in the war effort. The first cooperative of sugarcane planters was established with the creation of the Caeté mill.[5]

Intellectual activities also developed, not only with the Historic Institute, but also with the creation of the Academia Alagoana de Letras, in 1919,[42] and the formation of literary centers for young people such as the Academia dos Dez Unidos, the Cenáculo Alagoano de Letras, and the Grêmio Literário Guimarães Passos.[5] In 1931, the Law School[43] was founded, and in 1954 the School of Economic Sciences.[44] Later, these two faculties, plus those of dentistry, medicine, engineering and social work, merged to form the Federal University of Alagoas.[5]

The state political struggles gained strength in the 1950s. During the attempted impeachment of Governor Muniz Falcão in 1957, a shootout in the Legislative Assembly of Alagoas caused the death of Congressman Humberto Mendes, the governor's father-in-law. Throughout the second half of the 20th century, political tension remained, while the gains from the sal-gema, sugar and petroleum did not benefit the population.[5]

In 1979, former governor Arnon de Melo, then a senator, got the military government to appoint his son Fernando Afonso Collor de Melo as mayor of Maceió.[45] In 1988, an agreement between Collor, then governor, and the sugar and alcohol mills, the main contributors to the state's value-added tax, allowed them to reduce their tax revenues.[5] The revenue shortfall aggravated the state's historic social and economic crisis and generated a bankruptcy situation that led the federal government to an unofficial intervention in 1997.[46] After a new Treasury Secretary was appointed, Governor Divaldo Suruagy stepped aside, ceding the post to the vice-governor.[46]

21st Century

After the scandal that led Renan Calheiros to resign as president of the Brazilian Federal Senate in 2007,[47] his son Renan Filho (PMDB) was elected mayor of Murici in October 2008.[48] The mayor of Maceió, Cícero Almeida (PP), was reelected with 81.49% of the votes.[49]

In September 2008, the president of the Legislative Assembly of Alagoas, Antonio Albuquerque (PT do B), was removed from office[50] for being the main suspect in the detour of R$ 280 million from the legislative branch, investigated by Operation Taturana.[51] Fourteen deputies were indicted[52] and deputy Fernando Toledo (PSDB) took over the presidency of the branch.[53] In July 2009, the president of the Supreme Federal Court, Minister Gilmar Mendes, ordered that eight of the 14 deputies return to the Assembly, including Antonio Albuquerque.[54]

In October 2010, Teotônio Vilela Filho (PSDB) was reelected governor in the first round with 52.74% of the votes against his opponent, candidate Ronaldo Lessa (PDT).[55]

In October 2014, Renan Calheiros Filho (MDB-AL) was elected governor of the state of Alagoas in the first round with more than 52.16% of the valid votes. In 2018, Renan Filho was re-elected in the first round with 77.30% of the valid votes.

In the 2022 election, Paulo Suruagy do Amaral Dantas (MDB-AL) went to the second round with Rodrigo Cunha (Brazil Union-AL), the election was close but Paulo Dantas won with 52.33% of the valid votes.

Bibliography

- Alagoas: História. Vol. 1. São Paulo: Encyclopædia Britannica do Brasil Publicações Ltda. 1998. pp. 176–180.

- CIVITA, Roberto (2011). Almanaque Abril. São Paulo: Abril. p. 670.

References

- PIMENTEL, Jair Barbosa. "A História de Alagoas". Mais Alagoas UOL. Retrieved 2012-10-02.

- "História de Alagoas". Visite o Brasil. 2011. Archived from the original on 2012-01-11. Retrieved 2012-11-03.

- BUENO, E. Brasil: uma história. 2ª edição. São Paulo. Ática. 2003. p. 19.

- Biblioteca do IBGE. "História da Cidade da Barra de São Miguel". Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- «Alagoas: História». Nova Enciclopédia Barsa volume 1 ed. São Paulo: Encyclopædia Britannica do Brasil Publicações Ltda. 1998.

- "História do Rio São Francisco". Rota Brasil Oeste. 2001-11-01.

- "História da Praia do Francês". Guia Praia do Francês. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- "História de Penedo". Visite o Brasil. Archived from the original on 2011-05-27. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- "Dom Pero Fernandes Sardinha". Só Biografias. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- FATORELLI, Carlos (2010-03-25). "OS TERRATENENTES DO BRASIL (18): Termos Pejorativos Usados para Designar os Povos da América". Blog do Historiador. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- FRIGOLETTO DE MENEZES, Eduardo. "Evolução dos Municípios de Alagoas". Site Oficial do Autor. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- SILVA, Vilsemar. "FERNANDES CALABAR TRAIDOR OU HERÓI? O SURGIMENTO DE UMA NOVA VISÃO DE UMANTIGO HABITANTE DA COLÔNIA PORTUGUESA NA AMÉRICA DO SUL". Scribd. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- "História da Cidade de Santa Luzia do Norte". Municípios Alagoanos. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- "Refinaria do RN se chamará Clara Camarão". NoMinuto.com. 2008-09-10. Retrieved 2010-10-02.

- DIÉGUES JÚNIOR, Manuel (2006). O banguê nas Alagoas: traços da influência do sistema econômico do engenho. Federal University of Alagoas. ISBN 9788571771161. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- Prefeitura Municipal de Porto Calvo. "História de Porto Calvo". Porto Calvo Official Site. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "Quilombos". Sua pesquisa.com. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- VILELA, Túlio. "Quilombo dos Palmares". UOL Educação. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "Cronologia da História do Brasil". Ache Tudo e Região. 2010-06-27. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- "Quilombo dos Palmares". Memorial Pernambuco. Archived from the original on 2009-03-09. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "A Abolição". VivaBrasil.com. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "Linha do Tempo - Século 17". Portal Vermelho. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- ORLANDINI, Ricardo. "O Bandeirante Domingos Jorge Velho é contratado pelo governo colonial, para destruir o Quilombo dos Palmares". Site Oficial do Autor. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "Guerra dos Palmares". Info Escola. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- SILVA, Fernando Correia da. "Biografia de Zumbi dos Palmares". Vidas Lusófonas. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "Eventos do ano de 1710". Ponteiro.com.br. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "A Criação da Comarca". Destino Maceió. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- MENEZES, Mozart Vergetti (2005). Colonialismo em ação: Fiscalismo, Economia e Sociedade na Capitania da Paraíba. São Paulo: University of São Paulo. p. 122.

- "Prêmio: Frei João de Santa ngela Alagoas". 16º Concurso Nacional de Poesias. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- Prefeitura Municipal. "Origem". Marechal Deodoro Official Site. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- "8 de outubro: Dia do Nordestino". Cá Estamos Nós. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- SODRÉ, Nelson Werneck (1998). História da imprensa no Brasil. Mauad Editora. ISBN 9788585756888. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "História da Cidade de Maceió". Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- GUGLIOTTA, Alexandre Carlos (2007). "Entre trabalhadores imigrantes e nacionais: Tavares Bastos e seus projetos para a nação" (PDF). Fluminense Federal University. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "A História do Estado de Alagoas, A Colonização pelos portugueses. A fundação". HjoBrasil. Archived from the original on 2011-05-19. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- "História de Rio Largo". Municípios Alagoanos. Archived from the original on 2011-07-06. Retrieved 2010-10-09.

- Ticianeli (2020-05-11). "Companhia de Fiação e Tecidos Norte-Alagoas e a Fábrica de Saúde". História de Alagoas. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ARROXELAS JAYME, Manoel Claudino de. "Ata de fundação". Official Site of the Historic and Geographic Institute of Alagoas. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- PIMENTEL, Jair Barbosa (2011). "A História de Alagoas: Dos Caetés aos Marajás". Mais Alagoas UOL. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- "Lista de Governadores de Alagoas". Mais Alagoas UOL. Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Administração do Porto de Maceió (2011). "História do Porto". Administração do Porto de Maceió. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- "Site Oficial da Academia Alagoana de Letras". Retrieved 2010-10-10.

- Elaine Pimentel (2011-06-15). "A Faculdade de Direito de Alagoas". Federal University of Alagoas. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- "FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS ECONOMICAS DE ALAGOAS". ABC das Alagoas. Archived from the original on 2011-11-02. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- MENDES, Edja Jordan (2010-08-17). "Hereditariedade política e econômica». Observatório da Imprensa". Archived from the original on 2010-08-19. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- "Em 97, greve de policiais provocou renúncia de Suruagy". Folha de S.Paulo. 2007-07-19. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- Redação (2007-12-04). "Renan Calheiros renuncia ao cargo de presidente do Senado". UOL Notícias.

- Valderi Melo (2011-10-06). "Renan Filho é reeleito em Murici". Alagoas 24 Horas. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- "Cícero Almeida ganha com 81,49 % dos votos". O Estado de S. Paulo. 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- FREIRE, Sílvia (2008-09-17). "Presidente da Assembleia de Alagoas é destituído do cargo". Folha de S.Paulo. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- OLIVEIRA, Deh (2008-07-04). "Justiça afasta mais dois deputados de Alagoas indiciados na Operação Taturana". Folha Online. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- PC do B (2009-02-10). "Ministério Público pede prisão de deputados alagoanos". Communist Party of Brazil. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- "Fernando Toledo é eleito presidente da Assembleia de Alagoas". Alagoas Notícias. Archived from the original on 2015-06-30. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- MADEIRO, Carlos (2009-07-13). "STF determina retorno de 8 deputados de Alagoas afastados por suspeita de corrupção". UOL Notícias Política. Retrieved 2011-11-06.

- Eleições 2010 (2010-10-31). "Teotônio Vilela bate ex-governadores e é reeleito em Alagoas". Terra Notícias. Archived from the original on 2012-12-15. Retrieved 2011-11-06.