History of antisemitism

The history of antisemitism, defined as hostile actions or discrimination against Jews as a religious or ethnic group, goes back many centuries, with antisemitism being called "the longest hatred".[1] Jerome Chanes identifies six stages in the historical development of antisemitism:[2]

- Pre-Christian anti-Judaism in Ancient Greece and Rome which was primarily ethnic in nature

- Christian antisemitism in antiquity and the Middle Ages which was religious in nature and has extended into modern times

- Muslim antisemitism which was—at least in its classical form—nuanced, in that Jews were a protected class

- Political, social and economic antisemitism during the Enlightenment and post-Enlightenment Europe which laid the groundwork for racial antisemitism

- Racial antisemitism that arose in the 19th century and culminated in Nazism

- Contemporary antisemitism which has been labeled by some as the new antisemitism

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

Chanes suggests that these six stages could be merged into three categories: "ancient antisemitism, which was primarily ethnic in nature; Christian antisemitism, which was religious; and the racial antisemitism of the 19th and 20th centuries".[2] In practice, it is difficult to differentiate antisemitism from the general ill-treatment of nations by other nations before the Roman period, but since the adoption of Christianity in Europe, antisemitism has undoubtedly been present. The Islamic world has also historically seen the Jews as outsiders. The coming of the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions in 19th-century Europe bred a new manifestation of antisemitism, based as much upon race as upon religion, which culminated in the Holocaust that occurred during World War II. The formation of the state of Israel in 1948 caused new antisemitic tensions in the Middle East.

Classical period

Early animosity towards Jews

Louis H. Feldman argues that "we must take issue with the communis sensus that the pagan writers are predominantly anti-Semitic".[3] He asserts that "one of the great puzzles that has confronted the students of anti-semitism is the alleged shift from pro-Jewish statements found in the first pagan writers who mention the Jews ... to the vicious anti-Jewish statements thereafter, beginning with Manetho about 270 BCE".[4] In view of Manetho's anti-Jewish writings, antisemitism may have originated in Egypt and been spread by "the Greek retelling of Ancient Egyptian prejudices".[5] As examples of pagan writers who spoke positively of Jews, Feldman cites Aristotle, Theophrastus, Clearchus of Soli and Megasthenes. Feldman concedes that after Manetho "the picture usually painted is one of universal and virulent anti-Judaism".

The first clear examples of anti-Jewish sentiment can be traced back to Alexandria in the 3rd century BCE.[6] Alexandrian Jewry were the largest Jewish community in the world and the Septuagint, a Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible, was produced there. Manetho, an Egyptian priest and historian of that time, wrote scathingly of the Jews and his themes are repeated in the works of Chaeremon, Lysimachus, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon, and in Apion and Tacitus.[6] Hecateus of Abdera is quoted by Flavius Josephus as having written about the time of Alexander the Great that the Jews "have often been treated injuriously by the kings and governors of Persia, yet can they not be dissuaded from acting what they think best; but that when they are stripped on this account, and have torments inflicted upon them, and they are brought to the most terrible kinds of death, they meet them after an extraordinary manner, beyond all other people, and will not renounce the religion of their forefathers".[7] One of the earliest anti-Jewish edicts, promulgated by Antiochus Epiphanes in about 170–167 BCE, sparked a revolt of the Maccabees in Judea.

The ancient Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes an attack on Jews in Alexandria in 38 CE in which thousands of Jews died.[8][9] The violence in Alexandria may have been caused by the Jews' being portrayed as misanthropic.[10] Tcherikover argues that the reason for the hatred of Jews in the Hellenistic period was their separateness in the Greek cities, the poleis.[11] However, Bohak has argued that early animosity against the Jews cannot be regarded as being anti-Judaic or antisemitic unless it arose from attitudes that were held against the Jews alone, because many Greeks showed animosity towards any group which they considered barbaric.[12]

Statements which exhibit prejudice against Jews and their religion can be found in the works of many pagan Greek and Roman writers.[13] Edward Flannery writes that it was the Jews' refusal to accept Greek religious and social standards that marked them out. Hecataeus of Abdera, a Greek historian of the early third century BCE, wrote that Moses "in remembrance of the exile of his people, instituted for them a misanthropic and inhospitable way of life". Manetho wrote that the Jews were expelled Egyptian lepers who had been taught "not to adore the gods" by Moses. The same themes appear in the works of Chaeremon, Lysimachus, Poseidonius, Apollonius Molon, and in Apion and Tacitus. Agatharchides of Cnidus wrote about the "ridiculous practices" of the Jews and he also wrote about the "absurdity of their Law", and he also wrote about how Ptolemy Lagus was able to invade Jerusalem in 320 BC because its inhabitants were observing the Sabbath.[6] Edward Flannery describes the form of antisemitism which existed in ancient times as being essentially "cultural, taking the shape of a national xenophobia which was played out in political settings".[14]

There is a recorded instance in which an Ancient Greek ruler, Antiochus Epiphanes, desecrated the Temple in Jerusalem and banned Jewish religious practices, such as circumcision, Shabbat observance and the study of Jewish religious books,[15] during the period when Ancient Greece dominated the eastern Mediterranean. Statements exhibiting prejudice towards Jews and their religion can also be found in the works of a few pagan Greek and Roman writers,[16] but the earliest occurrence of antisemitism has been the subject of debate among scholars, largely because different writers use different definitions of antisemitism. The terms "religious antisemitism" and "anti-Judaism" are sometimes used in reference to animosity towards Judaism as a religion rather than antisemitism, which is used in reference to animosity towards Jews as members of an ethnic or racial group.

Roman Empire

Relations between the Jews in Judea and the occupying Roman Empire were antagonistic from the very start and they resulted in several rebellions. It has been argued that European antisemitism has its roots in the Roman policy of religious persecution.[17]

Several ancient historians report that in 19 CE, the Roman emperor Tiberius expelled the Jews from Rome. According to the Roman historian Suetonius, Tiberius tried to suppress all foreign religions. In the case of the Jews, he sent young Jewish men, under the pretence of military service, to provinces which were noted for their unhealthy climate. He expelled all other Jews from the city, under threat of lifelong slavery for non-compliance.[18] Josephus, in his Jewish Antiquities,[19] confirms that Tiberius ordered all Jews to be banished from Rome. Four thousand Jews were sent to Sardinia but more Jews, who were unwilling to become soldiers, were punished. Cassius Dio reports that Tiberius banished most of the Jews, who had been attempting to convert the Romans to their religion.[20] Philo of Alexandria reported that Sejanus, one of Tiberius's lieutenants, may have been a prime mover in the persecution of the Jews.[21]

The Romans refused to permit the Jews to rebuild the Temple of Jerusalem after its destruction by Titus in 70 CE, imposed a tax on the Jews (Fiscus Judaicus) at the same time, ostensibly to finance the construction of the Temple of Jupiter in Rome, and renamed Judaea to Syria Palestina. The Jerusalem Talmud relates that, following the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE), the Romans killed many Jews, "killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils".[22] However, some historians argue that Rome brutally suppressed revolts in all of its conquered territories and they also point out that Tiberius expelled all adherents of foreign religions from Rome, not just the Jews.

Some accommodations, in fact, were later made with Judaism, and the Jews of the Diaspora had privileges that others did not have. Unlike other subjects of the Roman Empire, the Jews had the right to maintain their religion and they were not expected to accommodate themselves to local customs. Even after the First Jewish–Roman War, the Roman authorities refused to rescind Jewish privileges in some cities. And although Hadrian outlawed circumcision as a form of mutilation which was normally inflicted upon people who were unable to consent to it, he later exempted the Jews from the ban on circumcision.[23] According to the 18th-century historian Edward Gibbon, there was greater tolerance of the Jews from about 160 CE. Between 355 and 363 CE, Julian the Apostate permitted the Jews to rebuild the Second Temple of Jerusalem.

Rise of Christianity and Islam

The New Testament and early Christianity

Although most of the New Testament was written, ostensibly, by Jews who became followers of Jesus, there are a number of passages in the New Testament that some consider antisemitic, and they have been used for antisemitic purposes, including:[24][25][26]

- Jesus speaking to a group of Pharisees: "I know that you are descendants of Abraham; yet you seek to kill me, because my word finds no place in you ... You are of your father the devil, and your will is to do your father's desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, and has nothing to do with the truth, because there is no truth in him." (John 8:37–39, 44–47, RSV)

- After Pilate washes his hands and declares himself innocent of Jesus' blood, the Jewish crowd answers him, "His blood be on us and on our children!" (Matthew 27:25, RSV). In an essay regarding antisemitism, biblical scholar Amy-Jill Levine argues that this passage has caused more Jewish suffering throughout history than any other passage in the New Testament.[27]

- Saint Stephen speaking before a synagogue council just before his execution: "You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always resist the Holy Spirit. As your fathers did, so do you. Which of the prophets did your fathers not persecute? And they killed those who announced beforehand the coming of the Righteous One, whom you have now betrayed and murdered, you who received the law as delivered by angels and did not keep it." (Acts 7:51–53, RSV)

Muhammad, the Quran, and early Islam

The Quran, the holy book of Muslims, contains some verses that can be interpreted as expressing very negative views of some Jews.[28] After the Islamic prophet Muhammad moved to Medina in 622 CE, he made peace treaties with the Jewish tribes of Arabia and other tribes. However, the relationship between the followers of the new religion and the Jews of Medina later became bitter. At this point the Quran instructs Muhammad to change the direction of prayer from Jerusalem to Mecca, and from this point on, the tone of the verses of the Quran become increasingly hostile towards Jewry.[29]

In 627 CE, Jewish tribe Banu Qurayza of Medina violated a treaty with Muhammad by allying with the attacking tribes.[30] Subsequently, the tribe was charged with treason and besieged by the Muslims commanded by Muhammad himself.[31][32] The Banu Qurayza were forced to surrender and the men were beheaded, while all the women and children were taken captive and enslaved.[31][32][33][34][35] Several scholars have challenged the veracity of this incident, arguing that it was exaggerated or invented.[36][37][38] Later, several conflicts arose between Jews of Arabia and Muhammad and his followers, the most notable of which was in Khaybar, in which many Jews were killed and their properties seized and distributed amongst the Muslims.[39]

Late Roman Empire

When Christianity became the state religion of Rome in the 4th century, Jews became the victims of religious intolerance and political oppression. Christian literature began to display extreme hostility towards Jews, which occasionally resulted in attacks against them and the burning of their synagogues. The hostility against Jews was reflected in the edicts which were imposed upon them by church councils and state laws. In the early 4th century, intermarriage between unconverted Jews and Christians was prohibited by the provisions of the Synod of Elvira. The Council of Antioch (341) prohibited Christians from celebrating Passover with the Jews while the Council of Laodicea forbade Christians from keeping the Jewish Sabbath.[40] The Roman Emperor Constantine I instituted several laws concerning the Jews: they were forbidden to own Christian slaves and they were also forbidden to circumcise their slaves. The conversion of Christians to Judaism was also outlawed. Religious services were regulated, congregations were restricted, but Jews were allowed to enter Jerusalem on Tisha B'Av, the anniversary of the destruction of the Temple.

Discrimination against Jews became worse in the 5th century. The edicts of the Codex Theodosianus (438) barred Jews from the civil service, the army and the legal profession.[41] The Jewish Patriarchate was abolished and the scope of Jewish courts was restricted. Synagogues were confiscated and old synagogues could only be repaired if they were in danger of collapsing. Synagogues fell into ruin or they were converted to churches. Synagogues were destroyed in Tortona (350), Rome (388 and 500), Raqqa (388), Menorca (418), Daphne (near Antioch, 489 and 507), Genoa (500), Ravenna (495), Tours (585) and in Orléans (590). Other synagogues were confiscated: Urfa in 411, several in Judea between 419 and 422, Constantinople in 442 and 569, Antioch in 423, Vannes in 465, Diyarbakir in 500 Terracina in 590, Cagliari in 590 and Palermo in 590.[42]

Accusations that the Jews killed Jesus

Deicide is the killing of a god. In the context of Christianity, deicide refers to the responsibility for the death of Jesus. The accusation that the Jews committed deicide has been the most powerful warrant for antisemitism by Christians.[43] The earliest recorded instance of an accusation of deicide against the Jewish people as a whole – that they were collectively responsible for the death of Jesus – occurs in a sermon of 167 CE attributed to Melito of Sardis entitled Peri Pascha, On the Passover. This text blames the Jews for allowing King Herod and Caiaphas to execute Jesus. Melito does not attribute particular blame to Pontius Pilate, he only mentions that Pilate washed his hands of guilt.[44] The sermon is written in Greek, but it may have been an appeal to Rome to spare Christians at a time when Christians were widely being persecuted. The Latin word deicida (slayer of god), from which the word deicide is derived, was used in the 4th century by Peter Chrystologus in his sermon number 172.[45] Though not part of Roman Catholic dogma, many Christians, including members of the clergy, once held Jews collectively responsible for the death of Jesus.[46] According to this interpretation, both the Jews who were present at Jesus' death and the Jewish people collectively and for all time had committed the sin of deicide, or God-killing.[47]

Middle Ages

There was continuing hostility to Judaism from the late Roman period into medieval times. During the Middle Ages in Europe there was a full-scale persecution of Jews in many places, with blood libels, expulsions, forced conversions and killings. In the 12th century, there were Christians who believed that some, or possibly all, of the Jews possessed magical powers and had gained these powers from making a pact with the devil. Judensau images began to appear in Germany.

Although the Catholicised Visigothic kingdom in Spain issued a series of anti-Jewish edicts already in the 7th century,[48] persecution of Jews in Europe reached a climax during the Crusades. Anti-Jewish rhetoric such as the Goad of Love began to appear and affect public consciousness.[49] At the time of the First Crusade, in 1096, a German Crusade destroyed flourishing Jewish communities on the Rhine and the Danube. In the Second Crusade in 1147, the Jews in France were the victims of frequent killings and atrocities. Following the coronation of Richard the Lionheart in 1189, Jews were attacked in London. When king Richard left to join the Third Crusade in 1190, anti-Jewish riots broke out again in York and throughout England.[50][51] In the first large-scale persecution in Germany after the First Crusade, 100,000 Jews were killed by Rintfleisch knights in 1298.[52] The Jews were also subjected to attacks during the Shepherds' Crusades of 1251 and 1320. In the 1330s Jews were assaulted by the Armleder, led by Arnold von Uissigheim, starting in 1336 in Franconia and subsequently by John Zimberlin during 1338–9 in Alsace who attacked more than one hundred Jewish communities.[53][54] Following these crusades, Jews were subject to expulsions, including, in 1290, the banishing of all English Jews. In 1396, 100,000 Jews were expelled from France and in 1421, thousands were expelled from Austria. Many of those expelled fled to Poland.[55]

As the Black Death plague swept across Europe in the mid-14th century, annihilating more than half of the population, Jews often became the scapegoats. Rumors spread that they had caused this epidemic by deliberately poisoning wells, an accusation that appeared before in the 1321 leper scare. Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by the ensuing hatred and violence. Pope Clement VI tried to protect Jews by a papal bull dated July 6, 1348, and by an additional bull soon afterwards, but several months later, 900 Jews were burnt alive in Strasbourg, where the plague had not yet affected the city.[56] The Jews of Prague were attacked on Easter of 1389.[57] The massacres of 1391 marked a decline in the Golden Age for Spanish Jewry.[58]

Relations between Muslims and Jews in the Islamic world

From the 9th century onwards, the medieval Islamic world imposed dhimmi status on Christian and Jewish minorities. Nevertheless, Jews were granted more freedom to practise their religion in the Muslim world than they were in Christian Europe.[59] Jewish communities in Spain thrived under tolerant Muslim rule during the Spanish Golden Age and Cordova became a centre of Jewish culture.[60]

However, the entrance of the Almoravides from North Africa in the 11th century saw harsh measures taken against both Christians and Jews.[60] As part of this repression there were pogroms against Jews in Cordova in 1011 and in Granada in 1066.[61][62][63] The Almohads, who by 1147 had taken control of the Almoravids' Maghribi and Andalusian territories,[64] took a less tolerant view still and treated the dhimmis harshly. Faced with the choice of either death or conversion, many Jews and Christians took a third option if they could, and fled.[65][66][67] Some, such as the family of Maimonides, went east to more tolerant Muslim lands,[65] while others went northward to settle in the growing Christian kingdoms.[68][69] At certain times in the Middle Ages, in Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Yemen, decrees ordering the destruction of synagogues were enacted. Jews were forced to convert to Islam or face death in parts of Yemen, Morocco and Baghdad.[70] 6,000 Jews were killed by a Muslim mob during the 1033 Fez massacre. There were further massacres in Fez in 1276 and 1465,[71][72][73] and in Marrakesh in 1146 and 1232.[73]

Occupational and other restrictions

Restrictions upon Jewish occupations were imposed by Christian authorities. Local rulers and church officials closed many professions to Jews, pushing them into marginal roles which were considered socially inferior, such as tax and rent collecting and moneylending, occupations which were only tolerated as a "necessary evil". At that time, Catholic doctrine taught the view that lending money for interest was a sin, and an occupation which Christians were forbidden to engage in. Not being subject to this restriction, insofar as loans to non-Jews were concerned, Jews made this business their own, despite possible criticism of usury in the Torah and later sections of the Hebrew Bible. This led to many negative stereotypes of Jews as insolent, greedy usurers and the tensions between creditors (typically Jews) and debtors (typically Christians) added to social, political, religious, and economic strains. Peasants who were forced to pay their taxes to Jews could see them as personally taking their money while unaware of those on whose behalf these Jews worked.

Jews were subject to a wide range of legal disabilities and restrictions throughout the Middle Ages, some of which lasted until the end of the 19th century. Even moneylending and peddling were at times forbidden to them. The number of Jews permitted to reside in different places was limited; they were concentrated in ghettos and were not allowed to own land; they were subject to discriminatory taxes on entering cities or districts other than their own and were forced to swear special Jewish Oaths, and they suffered a variety of other measures. The Fourth Lateran Council in 1215 decreed that Jews and Muslims must wear distinguishing clothing.[74] The most common such clothing was the Jewish hat, which was already worn by many Jews as a self-identifying mark, but was now often made compulsory.[75]

The Jewish badge was introduced in some places; it could be a coloured piece of cloth in the shape of a circle, strip, or the tablets of the law (in England), and was sewn onto the clothes.[76] Elsewhere special colours of robe were specified. Implementation was in the hands of local rulers but by the following century laws had been enacted covering most of Europe. In many localities, members of Medieval society wore badges to distinguish their social status. Some badges (such as those worn by guild members) were prestigious, while others were worn by ostracised outcasts such as lepers, reformed heretics and prostitutes. As with all sumptuary laws, the degree to which these laws were followed and enforced varied greatly. Sometimes, Jews sought to evade the badges by paying what amounted to bribes in the form of temporary "exemptions" to kings, which were revoked and re-paid for whenever the king needed to raise funds. By the end of the Middle Ages, the hat seems to have become rare, but the badge lasted longer and remained in some places until the 18th century.

Crusades

The Crusades were a series of military campaigns sanctioned by the Papacy in Rome, which took place from the end of the 11th century until the 13th century. They began as endeavors to recapture Jerusalem from the Muslims but developed into territorial wars.

The People's Crusade that accompanied the First Crusade attacked Jewish communities in Germany, France, and England, and killed many Jews. Entire communities, like those of Treves, Speyer, Worms, Mainz, and Cologne, were murdered by armed mobs. About 12,000 Jews are said to have perished in the Rhineland cities alone between May and July 1096. Before the Crusades, Jews had practically a monopoly on the trade in Eastern products, but the closer connection between Europe and the East brought about by the Crusades raised up a class of Christian merchant traders, and from this time onwards, restrictions on the sale of goods by Jews became frequent. The religious zeal fomented by the Crusades at times burned as fiercely against Jews as against Muslims, although attempts were made by bishops during the first Crusade and by the papacy during the Second Crusade to stop Jews from being attacked. Both economically and socially, the Crusades were disastrous for European Jews. They prepared the way for the anti-Jewish legislation of Pope Innocent III.

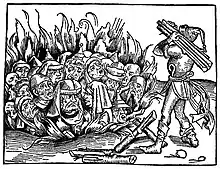

The Jewish defenders of Jerusalem retreated to their synagogue to "prepare for death" once the Crusaders had breached the outer walls of the city during the siege of 1099.[77][78] The chronicle of Ibn al-Qalanisi states that the building was set on fire whilst the Jews were still inside.[79] The Crusaders were supposedly reported as hoisting up their shields and singing "Christ We Adore Thee!" while they encircled the burning building."[80] Following the siege, Jews captured from the Dome of the Rock, along with native Christians, were made to clean the city of the slain.[81] Numerous Jews and their holy books (including the Aleppo Codex) were held ransom by Raymond of Toulouse.[82] The Karaite Jewish community of Ashkelon (Ascalon) reached out to their coreligionists in Alexandria to first pay for the holy books and then rescued pockets of Jews over several months.[81] All that could be ransomed were liberated by the summer of 1100. The few who could not be rescued were either converted to Christianity or murdered.[83]

In the County of Toulouse, in southern France, toleration and favour shown to Jews was one of the main complaints of the Roman Church against the Counts of Toulouse at the beginning of the 13th century. Organised and official persecution of the Jews became a normal feature of life in southern France only after the Albigensian Crusade, because it was only then that the Church became powerful enough to insist that measures of discrimination be applied.[84] In 1209, stripped to the waist and barefoot, Raymond VI of Toulouse was obliged to swear that he would no longer allow Jews to hold public office. In 1229 his son Raymond VII underwent a similar ceremony.[85] In 1236, Crusaders attacked the Jewish communities of Anjou and Poitou, killing 3,000 and baptizing 500.[86] Two years after the 1240 disputation of Paris, twenty-four wagons piled with hand-written Talmudic manuscripts were burned in the streets.[87] Other disputations occurred in Spain, followed by accusations against the Talmud.

Blood libels and host desecrations

On many occasions, Jews were accused of drinking the blood of Christian children in mockery of the Christian Eucharist. According to the authors of these so-called blood libels, the 'procedure' for the alleged sacrifice was something like this: a child who had not yet reached puberty was kidnapped and taken to a hidden place. The child would be tortured by Jews, and a crowd would gather at the place of execution (in some accounts the synagogue itself) and engage in a mock tribunal to try the child. The child would be presented to the tribunal naked and tied and eventually be condemned to death. In the end, the child would be crowned with thorns and tied or nailed to a wooden cross. The cross would be raised, and the blood dripping from the child's wounds would be caught in bowls or glasses and then drunk. Finally, the child would be killed with a thrust through the heart from a spear, sword, or dagger. Its dead body would be removed from the cross and concealed or disposed of, but in some instances rituals of black magic would be performed on it. This method, with some variations, can be found in all the alleged Christian descriptions of ritual murder by Jews.

The story of William of Norwich (d. 1144) is often cited as the first known accusation of ritual murder against Jews. The Jews of Norwich, England were accused of murder after a Christian boy, William, was found dead. It was claimed that the Jews had tortured and crucified him. The legend of William of Norwich became a cult, and the child acquired the status of a holy martyr.[88] Little Saint Hugh of Lincoln (d. 1255), in the 13th century, reputedly had his belly cut open and his entrails removed for some occult purpose, such as a divination ritual, after being taken from a cross. Simon of Trent (d. 1475), in the fifteenth century, was held over a large bowl so that all of his blood could be collected, it was alleged.

During the Middle Ages, such blood libels were directed against Jews in many parts of Europe. The believers in these false accusations reasoned that the Jews, having crucified Jesus, continued to thirst for pure and innocent blood, at the expense of innocent Christian children.[89] Jews were also sometimes falsely accused of desecrating consecrated hosts in a reenactment of the Crucifixion; this crime was known as host desecration and it carried the death penalty.

Expulsions from France and England

The practice of expelling Jews, the confiscation of their property and further ransom for their return was utilized to enrich the French crown during the 13th and 14th centuries. The most notable such expulsions were from Paris by Philip Augustus in 1182, from the whole of France by Louis IX in 1254, by Philip IV in 1306, by Charles IV in 1322 and by Charles VI in 1394.[90]

Jewish expulsions inside England took place in Bury St. Edmunds in 1190, Newcastle in 1234, Wycombe in 1235, Southampton in 1236, Berkhamsted in 1242 and Newbury in 1244.[91] Simon de Montfort banished the Jews of Leicester in 1231.[92] During the Second Barons' War in the 1260s, Simon de Montfort's followers ravaged the Jewries of London, Canterbury, Northampton, Winchester, Cambridge, Worcester and Lincoln in an effort to destroy the records of their debts to moneylenders.[91] To finance his war against Wales in 1276, Edward I of England taxed Jewish moneylenders. When the moneylenders could no longer pay the tax, they were accused of disloyalty. Already restricted to a limited number of occupations, Edward abolished their "privilege" to lend money, restricted their movements and activities and forced Jews to wear a yellow patch. The heads of Jewish households were then arrested with over 300 being taken to the Tower of London and executed. Others were killed in their homes. All Jews were banished from the country in 1290,[93] where it was possible that hundreds were killed or drowned while trying to leave the country.[94] All the money and property of these dispossessed Jews was confiscated. No Jews were known to be in England thereafter until 1655, when Oliver Cromwell reversed the policy.

Expulsions from the Holy Roman Empire

In Germany, part of the Holy Roman Empire, persecutions and formal expulsions of the Jews were liable to occur at intervals, although it should be said that this was also the case for other minority communities, whether religious or ethnic. There were particular outbursts of riotous persecution in the Rhineland massacres of 1096 accompanying the lead-up to the First Crusade, many involving the crusaders as they travelled to the East. There were many local expulsions from cities by local rulers and city councils. The Holy Roman Emperor generally tried to restrain persecution, if only for economic reasons, but he was often unable to exert much influence. As late as 1519, the Imperial city of Regensburg took advantage of the recent death of Emperor Maximilian I to expel its 500 Jews.[95] At this period the rulers of the eastern edges of Europe, in Poland, Lithuania and Hungary, were often receptive to Jewish settlement, and many Jews moved to these regions.[96]

The Black Death

Hundreds of Jewish communities were destroyed by violence during the ravages of the Black Death, particularly in the Iberian peninsula and in the Germanic Empire. In Provence, 40 Jews were burnt in Toulon as quickly after the outbreak as April 1348.[56] "Never mind that Jews were not immune from the ravages of the plague; they were tortured until they 'confessed' to crimes that they could not possibly have committed. In one such case, a man named Agimet was ... coerced to say that Rabbi Peyret of Chambéry (near Geneva) had ordered him to poison the wells in Venice, Toulouse, and elsewhere. In the aftermath of Agimet's 'confession', the Jews of Strasbourg were burned alive on February 14, 1349."[97]

Early modern period

Spain and Portugal

In the Catholic kingdoms of late medieval and early modern Spain, oppressive policies and attitudes led many Jews to embrace Christianity.[98] Such Jews were known as conversos or Marranos.[98] Suspicions that they might still secretly be adherents of Judaism led Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile to institute the Spanish Inquisition.[98] The Inquisition used torture to elicit confessions and delivered judgment at public ceremonials known as autos de fe before they gave their victims over to the secular authorities for punishment.[99] Under this dispensation, some 30,000 were condemned to death and executed by being burnt alive.[100] In 1492, Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile issued an edict of expulsion of Jews from Spain, giving Jews four months to either convert to Christianity or leave the country.[101] Some 165,000 emigrated and some 50,000 converted to Christianity.[102] The same year the order of expulsion arrived in Sicily and Sardinia, belonging to Spain.[103]

Portugal followed suit in December 1496. However, those expelled could only leave the country in ships specified by the King. When those who chose to leave the country arrived at the port in Lisbon, they were met by clerics and soldiers who used force, coercion and promises to baptize them and prevent them from leaving the country. This episode technically ended the presence of Jews in Portugal. Afterwards, all converted Jews and their descendants would be referred to as New Christians or Conversos, and those were rumoured to practice crypto-Judaism were pejoratively labelled as Marranos. They were given a grace period of thirty years during which no inquiry into their faith would be allowed. This period was later extended until 1534. However, a popular riot in 1506 resulted in the deaths of up to four or five thousand Jews, and the execution of the leaders of the riot by King Manuel. Those labeled as New Christians were under the surveillance of the Portuguese Inquisition from 1536 until 1821.

Jewish refugees from Spain and Portugal, known as Sephardi Jews from the Hebrew word for Spain, fled to North Africa, Turkey and Palestine within the Ottoman Empire, and to Holland, France and Italy.[104] Within the Ottoman Empire, Jews could openly practise their religion. Amsterdam in Holland also became a focus for settlement by the persecuted Jews from many lands in succeeding centuries.[105] In the Papal states, Jews were forced to live in ghettos and subjected to several restrictions as part of the Cum nimis absurdum of 1555.[106]

Anti-Judaism and the Reformation

Martin Luther, a Lutheran Augustinian friar excommunicated by the Papacy for heresy,[107] and an ecclesiastical reformer whose teachings inspired the Reformation, wrote antagonistically about Jews in his pamphlet On the Jews and Their Lies, written in 1543. He portrays the Jews in extremely harsh terms, excoriates them and provides detailed recommendations for a pogrom against them, calling for their permanent oppression and expulsion. At one point he writes: "...we are at fault in not slaying them..." a passage that "may be termed the first work of modern antisemitism, and a giant step forward on the road to the Holocaust."[108]

Luther's harsh comments about the Jews are seen by many as a continuation of medieval Christian antisemitism. Muslow and Popkin assert that, "the antisemitism of the early modern period was even worse than that of the Middle Ages; and nowhere was this more obvious than in those areas which roughly encompass modern-day Germany, especially among Lutherans."[109] In his final sermon shortly before his death, however, Luther preached: "We want to treat them with Christian love and to pray for them, so that they might become converted and would receive the Lord."[110]

Canonization of Simon of Trent

Simon of Trent was a boy from the city of Trento, Italy, who was found dead at the age of two in 1475, having allegedly been kidnapped, mutilated, and drained of blood. His disappearance was blamed on the leaders of the city's Jewish community, based on confessions extracted under torture, in a case that fueled the rampant antisemitism of the time. Simon was regarded as a saint, and was canonized by Pope Sixtus V in 1588.

Seventeenth century

During the 1614 Fettmilch uprising, mobs led by Vincenz Fettmilch looted the Jewish ghetto of Frankfurt, expelling Jews from the city. Two years later emperor Matthias executed Fettmilch and made the Jews return to the city under protection by imperial soldiers.[111]

In the mid-17th century, Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch Director-General of the colony of New Amsterdam, later New York City, sought to bolster the position of the Dutch Reformed Church by trying to stem the religious influence of Jews, Lutherans, Catholics and Quakers. He stated that Jews were "deceitful", "very repugnant", and "hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ". However, religious plurality was already a cultural tradition and a legal obligation in New Amsterdam and in the Netherlands, and his superiors at the Dutch West India Company in Amsterdam overruled him.

During the mid-to-late-17th century the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth was devastated by several conflicts, in which the Commonwealth lost over a third of its population (over 3 million people). The decrease of the Jewish population during that period is estimated at 100,000 to 200,000, including emigration, deaths from diseases and captivity in the Ottoman Empire.[112][113] These conflicts began in 1648 when Bohdan Khmelnytsky instigated the Khmelnytsky Uprising against the Polish aristocracy and the Jews who administered their estates.[114] Khmelnytsky's Cossacks massacred tens of thousands of Jews in the eastern and southern areas that he controlled (now Ukraine). This persecution led many Jews to pin their hopes on a man called Shabbatai Zevi who emerged in the Ottoman Empire at this time and proclaimed himself Messiah in 1665. However his later conversion to Islam dashed these hopes and led many Jews to discredit the traditional belief in the coming of the Messiah as the hope of salvation.[115]

In the Zaydi imamate of Yemen, Jews were also singled out for discrimination in the 17th century, which culminated in the general expulsion of all Jews from places in Yemen to the arid coastal plain of Tihamah and which became known as the Mawza Exile.[116]

Eighteenth century

In many European countries the 18th century "Age of Enlightenment" saw the dismantling of archaic corporate, hierarchical forms of society in favour of individual equality of citizens before the law. How this new state of affairs would affect previously autonomous, though subordinated, Jewish communities became known as the Jewish question. In many countries, enhanced civil rights were gradually extended to the Jews, though often only in a partial form and on condition that the Jews abandon many aspects of their previous identity in favour of integration and assimilation with the dominant society.[117]

According to Arnold Ages, Voltaire's "Lettres philosophiques, Dictionnaire philosophique, and Candide, to name but a few of his better known works, are saturated with comments on Jews and Judaism and the vast majority are negative".[118] Paul H. Meyer adds: "There is no question but that Voltaire, particularly in his later years, nursed a violent hatred of the Jews and it is equally certain that his animosity...did have a considerable impact on public opinion in France."[119] Thirty of the 118 articles in Voltaire's Dictionnaire philosophique concerned Jews and described them in consistently negative ways.[120]

In 1744, Frederick II of Prussia limited the number of Jews allowed to live in Breslau to only ten so-called "protected" Jewish families and encouraged a similar practice in other Prussian cities. In 1750 he issued the Revidiertes General Privilegium und Reglement vor die Judenschaft: forcing these "protected" Jews to "either abstain from marriage or leave Berlin."[121] In the same year, Archduchess of Austria Maria Theresa ordered Jews out of Bohemia but soon reversed her position, on condition that they pay for their readmission every ten years. This was known among the Jews as malke-geld (queen's money).[122] In 1752 she introduced a law limiting each Jewish family to one son. In 1782, Joseph II abolished most of these practices in his Toleranzpatent, on the condition that Yiddish and Hebrew were eliminated from public records and that judicial autonomy was annulled.[122] In 1768, thousands of Jews were killed by Cossack Haidamaks during the massacre of Uman in the Kingdom of Poland.[123]

Jews in Switzerland were greatly restricted in their freedom of work, movement and settlement, and in the 17th century, Aargau was the only federal condominium where they were tolerated. In 1774, the Jews were restricted to just two towns, Endingen and Lengnau. While the rural upper class pressed incessantly for their expulsion, the financial interests of the authorities prevented it. They imposed special taxes on peddling and cattle trading, the primary Jewish professions. The Jews were directly subordinate to the governor; from 1696, they were compelled to renew a (costly) letter of protection every 16 years.[124]

During this period, Jews and Christians were not allowed to live under the same roof, nor were Jews allowed to own land or houses. They were taxed at a much higher rate than others and, in 1712, a pogrom took place in Lengnau, resulting in considerable property destruction.[125] In 1760, they were further restricted regarding marriages and procreation. An exorbitant tax was levied on marriage licenses; oftentimes, they were outright refused. This remained the case until the 19th century.[124]

In accordance with the anti-Jewish precepts of the Russian Orthodox Church,[126] Russia's discriminatory policies towards Jews intensified when the partition of Poland in the 18th century resulted, for the first time in Russian history, in the possession of land with a large population of Jews.[127] This land was designated as the Pale of Settlement from which Jews were forbidden to migrate into the interior of Russia.[127] In 1772, the empress of Russia Catherine II forced the Jews of the Pale of Settlement to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland.[128]

Nineteenth century

Following legislation supporting the equality of French Jews with other citizens during the French Revolution, similar laws promoting Jewish emancipation were enacted in the early 19th century in those parts of Europe over which France had influence.[129][130] The old laws restricting them to ghettos, as well as the many laws that limited their property rights, rights of worship and occupation, were rescinded.

Despite laws granting legal and political equality to Jews in a number of countries, traditional cultural discrimination and hostility to Jews on religious grounds persisted and was supplemented by racial antisemitism.

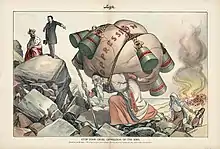

Catholic counter-revolution

Despite this, traditional discrimination and hostility to Jews on religious grounds persisted and was supplemented by racial antisemitism, encouraged by the work of racial theorists such as the royalist Joseph Arthur de Gobineau and particularly his Essay on the Inequality of the Human Race of 1853–55. Nationalist agendas based on ethnicity, known as ethnonationalism, usually excluded the Jews from the national community as an alien race.[131] Allied to this were theories of Social Darwinism, which stressed a putative conflict between higher and lower races of human beings. Such theories, usually posited by white Europeans, advocated the superiority of white Aryans to Semitic Jews.[132]

The counter-revolutionary Catholic royalist Louis de Bonald stands out among the earliest figures to explicitly call for the reversal of Jewish emancipation in the wake of the French Revolution.[133][134] Bonald's attacks on the Jews are likely to have influenced Napoleon's decision to limit the civil rights of Alsatian Jews.[135][136][137][138] Bonald's article Sur les juifs (1806) was one of the most venomous screeds of its era and furnished a paradigm which combined anti-liberalism, traditional Christian antisemitism, and the identification of Jews with bankers and finance capital, which would in turn influence many subsequent right-wing reactionaries such as Roger Gougenot des Mousseaux, Charles Maurras, and Édouard Drumont, nationalists such as Maurice Barrès and Paolo Orano, and antisemitic socialists such as Alphonse Toussenel and Henry Hyndman.[133][139][140] Bonald furthermore declared that the Jews were an "alien" people, a "state within a state", and should be forced to wear a distinctive mark to more easily identify and discriminate against them.[133][141]

In the 1840s, the popular counter-revolutionary Catholic journalist Louis Veuillot propagated Bonald's arguments against the Jewish "financial aristocracy" along with vicious attacks against the Talmud and the Jews as a "deicidal people" driven by hatred to "enslave" Christians.[142][141] Gougenot des Mousseaux's Le Juif, le judaïsme et la judaïsation des peuples chrétiens (1869) has been called a "Bible of modern antisemitism" and was translated into German by Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg.[141] In Italy, the Jesuit priest Antonio Bresciani's highly popular novel 1850 novel L'Ebreo di Verona (The Jew of Verona) shaped religious antisemitism for decades, as did his work for La Civiltà Cattolica, which he helped launch.[143][144] In the Papal States, Jews were baptized involuntarily, and, even when such baptisms were illegal, forced to practice the Christian religion. In some cases, the state separated them from their families, of which the Edgardo Mortara account is one of the most widely publicized instances of acrimony between Catholics and Jews in the second half of the 19th century.[145]

Germany

Civil rights granted to Jews in Germany, following the occupation of that country by the French under Napoleon, were rescinded after his defeat. Pleas to retain them by diplomats at the Congress of Vienna peace conference (1814–5) were unsuccessful.[146] In 1819, German Jews were attacked in the Hep-Hep riots.[147] Full Jewish emancipation was not granted in Germany until 1871, when the country was united under the Hohenzollern dynasty.[148]

In his 1843 essay On the Jewish Question, Karl Marx said the god of Judaism is money and accused the Jews of corrupting Christians.[149] In 1850, German composer Richard Wagner published Das Judenthum in der Musik ("Jewishness in Music") under a pseudonym in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik. The essay began as an attack on Jewish composers, particularly Wagner's contemporaries (and rivals) Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer, but expanded to accuse Jewish influences more widely of being a harmful and alien element in German culture.

The term "antisemitism" was coined by the German agitator and publicist, Wilhelm Marr in 1879. In that year, Marr founded the Antisemites League and published a book called Victory of Jewry over Germandom.[150] The late 1870s saw the growth of antisemitic political parties in Germany. These included the Christian Social Party, founded in 1878 by Adolf Stoecker, the Lutheran chaplain to Kaiser Wilhelm I, as well as the German Social Antisemitic Party and the Antisemitic People's Party. However, they did not enjoy mass electoral support and at their peak in 1907, had only 16 deputies out of a total of 397 in the parliament.[151]

France

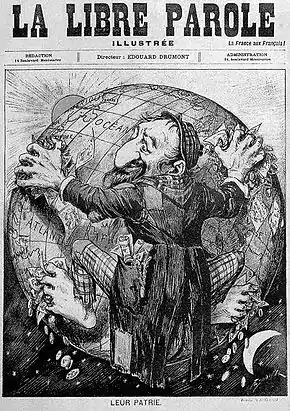

The defeat of France in the Franco-Prussian War (1870–71) was blamed by some on the Jews. Jews were accused of weakening the national spirit through association with republicanism, capitalism and anti-clericalism, particularly by authoritarian, right wing, clerical and royalist groups. These accusations were spread in antisemitic journals such as La Libre Parole, founded by Edouard Drumont and La Croix, the organ of the Catholic order of the Assumptionists. Between 1882 and 1886 alone, French priests published twenty antisemitic books blaming France's ills on the Jews and urging the government to consign them back to the ghettos, expel them, or hang them from the gallows.[141]

Financial scandals such as the collapse of the Union Generale Bank and the collapse of the French Panama Canal operation were also blamed on the Jews. The Dreyfus affair saw a Jewish military officer named Captain Alfred Dreyfus falsely accused of treason in 1895 by his army superiors and sent to Devil's Island after being convicted. Dreyfus was acquitted in 1906, but the case polarised French opinion between antisemitic authoritarian nationalists and philosemitic anti-clerical republicans, with consequences which were to resonate into the 20th century.[152]

Switzerland

Having been restricted in their rights of work and movement since the Middle Ages, on 5 May 1809, Jews were finally declared Swiss citizens and given limited rights regarding trade and farming. They were still restricted to Endingen and Lengnau until 7 May 1846, when their right to move and reside freely within the canton of Aargau was granted. On 24 September 1856, the Swiss Federal Council granted them full political rights within Aargau, as well as broad business rights; however, the majority Christian population did not fully abide by these new liberal laws. The time of 1860 saw the canton government voting to grant suffrage in all local rights and to give their communities autonomy. Before the law was enacted however, it was repealed due to vocal opposition led by Johann Nepomuk Schleuniger and the Ultramonte Party.[125] In 1866, a referendum granted all Jews full citizenship rights in Switzerland.[124] However, they did not receive all of the rights in Endingen and Lengnau until a resolution of the Grand Council, on 15 May 1877, when Jewish citizens were given charters under the names of New Endingen and New Lengnau, finally granting them full citizenship.[125]

United States

Between 1881 and 1920, approximately three million Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe migrated to America, many of them fleeing pogroms and the difficult economic conditions which were widespread in much of Eastern Europe during this time. Many Americans distrusted these Jewish immigrants.[153] Along with Italians, Irish and other Eastern and Southern Europeans, Jews faced discrimination in the United States in employment, education and social advancement. American groups like the Immigration Restriction League, criticized these new arrivals along with immigrants from Asia and southern and eastern Europe, as culturally, intellectually, morally, and biologically inferior. Despite these attacks, very few Eastern European Jews returned to Europe for whatever privations they faced, their situation in the U.S. was still improved.

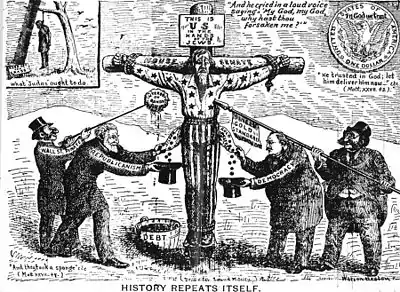

Beginning in the early 1880s, declining farm prices also prompted elements of the Populist movement to blame the perceived evils of capitalism and industrialism on Jews because of their alleged racial/religious inclination for financial exploitation and, more specifically, because of the alleged financial manipulations of Jewish financiers such as the Rothschilds.[154] Although Jews played only a minor role in the nation's commercial banking system, the prominence of Jewish investment bankers such as the Rothschilds in Europe, and Jacob Schiff, of Kuhn, Loeb & Co. in New York City, made the claims of antisemites believable to some. The Morgan Bonds scandal injected populist antisemitism into the 1896 presidential campaign. It was disclosed that President Grover Cleveland had sold bonds to a syndicate which included J. P. Morgan and the Rothschilds house, bonds which that syndicate was now selling for a profit. The Populists used it as an opportunity to uphold their view of history, and prove to the nation that Washington and Wall Street were in the hands of the international Jewish banking houses. Another focus of antisemitic feeling was the allegation that Jews were at the center of an international conspiracy to fix the currency and thus the economy to a single gold standard.[155]

Russia

Since 1827, Jewish minors were conscripted into the cantonist schools for a 25-year military service.[156] Policy towards Jews was liberalised somewhat under Tsar Alexander II,[157] but antisemitic attitudes and long-standing repressive policies against Jews were intensified after Alexander II was assassinated on 13 March 1881, culminating in widespread anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire which lasted for three years.[158] A hardening of official attitudes under Tsar Alexander III and his ministers, resulted in the May Laws of 1882, which severely restricted the civil rights of Jews within the Russian Empire. The Tsar's minister Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev stated that the aim of the government with regard to the Jews was that: "One third will die out, one third will leave the country and one third will be completely dissolved [into] the surrounding population".[158] In the event, a mix of pogroms and repressive legislation did indeed result in the mass emigration of Jews to western Europe and America. Between 1881 and the outbreak of the First World War, an estimated two and half million Jews left Russia – one of the largest mass migrations in recorded history.[150][159]

The Muslim world

Historian Martin Gilbert writes that it was in the 19th century that the position of Jews worsened in Muslim countries.[160][161] According to Mark Cohen in The Oxford Handbook of Jewish Studies, most scholars conclude that Arab antisemitism in the modern world arose in the 19th century, against the backdrop of conflicting Jewish and Arab nationalisms, and it was primarily imported into the Arab world by nationalistically minded Christian Arabs (and only subsequently was it "Islamized").[162]

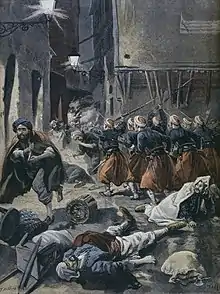

Hundreds of Algerian Jews were killed in 1805.[163] There was a massacre of Iraqi Jews in Baghdad in 1828.[164] In 1839, in the eastern Persian city of Meshed, a mob burst into the Jewish Quarter, burned the synagogue and destroyed the Torah scrolls, and it was only by forced conversion that a massacre was averted.[160] There was a massacre of Jews in Barfurush in 1867.[164] In 1840, in the Damascus affair, the Jews of Damascus were falsely accused of having ritually murdered a Christian monk and his Muslim servant and of having used their blood to bake Passover bread. In 1859, some 400 Jews in Morocco were killed in Mogador. In 1864, around 500 Jews were killed in Marrakech and Fez in Morocco. In 1869, 18 Jews were killed in Tunis, and an Arab mob looted Jewish homes and stores, and burned synagogues, on Jerba Island.

Concerning the life of Persian Jews in the middle of the 19th century, a contemporary author wrote:

...they are obliged to live in a separate part of town... for they are considered as unclean creatures... Under the pretext of their being unclean, they are treated with the greatest severity and should they enter a street, inhabited by Mussulmans, they are pelted by the boys and mobs with stones and dirt... For the same reason, they are prohibited to go out when it rains; for it is said the rain would wash dirt off them, which would sully the feet of the Mussulmans... If a Jew is recognized as such in the streets, he is subjected to the greatest insults. The passers-by spit in his face, and sometimes beat him... unmercifully... If a Jew enters a shop for anything, he is forbidden to inspect the goods... Should his hand incautiously touch the goods, he must take them at any price the seller chooses to ask for them.[165]

One symbol of Jewish degradation was the phenomenon of stone-throwing at Jews by Muslim children. A 19th-century traveler observed: "I have seen a little fellow of six years old, with a troop of fat toddlers of only three and four, teaching [them] to throw stones at a Jew, and one little urchin would, with the greatest coolness, waddle up to the man and literally spit upon his Jewish gaberdine. To all this the Jew is obliged to submit; it would be more than his life was worth to offer to strike a Mahommedan."[164] In 1891, the leading Muslims in Jerusalem asked the Ottoman authorities in Constantinople to prohibit the entry of Jews arriving from Russia.[160]

Twentieth century

In the 20th century, antisemitism and Social Darwinism culminated in a systematic campaign of genocide, called the Holocaust, in which some six million Jews were exterminated in German-occupied Europe between 1941 and 1945 under the National Socialist regime of Adolf Hitler.[166]

Russia

In Russia, under the Tsarist regime, antisemitism intensified in the early years of the 20th century and was given official favour when the secret police forged the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document purported to be a transcription of a plan by Jewish elders to achieve global domination.[167] Violence against the Jews in the Kishinev pogrom in 1903 was continued after the 1905 revolution by the activities of the Black Hundreds.[168] The Beilis Trial of 1913 showed that it was possible to revive the blood libel accusation in Russia.

The 1917 Bolshevik Revolution ended official discrimination against the Jews but was followed, however, by massive anti-Jewish violence by the anti-Bolshevik White Army and the forces of the Ukrainian People's Republic in the Russian Civil War. From 1918 to 1921, between 100,000 and 150,000 Jews were slaughtered during the White Terror.[169] White emigres from revolutionary Russia fostered the idea that the Bolshevik regime, with its many Jewish members, was a front for the global Jewish conspiracy, outlined in the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which had by now achieved wide circulation in the west.[170] The pogroms were committed not only by White forces, but also by Red forces, local warlords, and ordinary Ukrainian and Polish citizens.[171]

France

In France, antisemitic agitation was promoted by right-wing groups such as Action Française, founded by Charles Maurras. These groups were critical of the whole political establishment of the Third Republic. Following the Stavisky Affair, in which a Jewish man named Serge Alexandre Stavisky was revealed to be involved in high-level political corruption, these groups encouraged serious rioting which almost toppled the government in the 6 February 1934 crisis.[172] The rise to prominence of the Jewish socialist Léon Blum, who became prime minister of the Popular Front Government in 1936, further polarised opinion within France. Action Française and other right-wing groups launched a vicious antisemitic press campaign against Blum which culminated in an attack in which he was dragged from his car and kicked and beaten whilst a mob screamed 'Death to the Jew!'[173] Catholic writers such as Ernest Jouin, who published the Protocols in French, seamlessly blended racial and religious antisemitism, as in his statement that "from the triple viewpoint of race, of nationality, and of religion, the Jew has become the enemy of humanity."[174] Pope Pius XI praised Jouin for "combating our mortal [Jewish] enemy" and appointed him to high papal office as a protonotary apostolic.[175][174]

Antisemitism was particularly virulent in Vichy France during World War II. The Vichy government openly collaborated with the Nazi occupiers to identify Jews for deportation. The antisemitic demands of right-wing groups were implemented under the collaborating Vichy regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain, following the defeat of the French by the German army in 1940. A law on the status of Jews of that year, followed by another in 1941, purged Jews from employment in administrative, civil service and judicial posts, from most professions and even from the entertainment industry – restricting them, mostly, to menial jobs. Vichy officials detained some 75,000 Jews who were then handed over to the Germans; approximated 72,500 Jews were murdered during the Holocaust in France.[176]

Nazism and the Holocaust

In Germany, following World War I, Nazism arose as a political movement incorporating racially antisemitic ideas, expressed by Adolf Hitler in his book Mein Kampf (German: My Struggle). After Hitler came to power in 1933, the Nazi regime sought the systematic exclusion of Jews from national life. Jews were demonized as the driving force of both international Marxism and capitalism. The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 outlawed marriage or sexual relationships between Jews and non-Jews.[177] Antisemitic propaganda by or on behalf of the Nazi Party began to pervade society. Especially virulent in this regard was Julius Streicher's publication Der Stürmer, which published the alleged sexual misdemeanors of Jews for popular consumption.[178] Mass violence against the Jews was encouraged by the Nazi regime, and on the night of 9–10 November 1938, dubbed Kristallnacht, the regime sanctioned the killing of Jews, the destruction of property and the torching of synagogues.[179] Already prior to the new European war, German authorities started rounding up thousands of Jews for their first concentration camps while many other German Jews fled the country or were forced to emigrate.

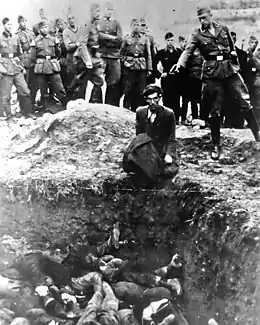

As Nazi control extended in the course of World War II, antisemitic laws, agitation and propaganda were brought to occupied Europe,[180] often building on local antisemitic traditions. In the German-occupied Poland, where over three million Jews had lived before the war in the largest Jewish population in Europe, Polish Jews were forced into newly established prison ghettos in 1940, including the Warsaw Ghetto for almost half million Jews.[181] Following the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, a systematic campaign of mass murder in that country was conducted against Soviet Jews (including former Polish Jews from Soviet-annexed territories) by Nazi death squads called the Einsatzgruppen, murdering over one million Jews and marking a turn from persecution to extermination.[182] In all, some six million Jews, about half of them from Poland, were murdered outright or indirectly through starvation, disease and overwork in German and collaborationist captivity between 1941 and 1945 in the genocide known as the Holocaust.[183][184][185]

On 20 January 1942, Reinhard Heydrich, deputed to find a "final solution to the Jewish question", chaired the Wannsee Conference at which all the ethnic Jews and many of part-Jews resident in Europe and North Africa were marked to be exterminated.[186] To implement this plan, the Jews from Poland, Germany, and various other countries would be transported to purpose-built extermination camps set up by Nazis in the occupied Poland and in Germany-annexed territories, where they were mostly murdered in gas chambers immediately upon their arrival. These camps, located at Auschwitz-Birkenau, Chełmno, Bełżec, Majdanek, Sobibór and Treblinka, accounted for about half of the total number of Jewish victims of Nazism.[187]

United States

Between 1900 and 1924, approximately 1.75 million Jews migrated to America's shores, the bulk of them were from Eastern Europe. Where before 1900, American Jews never amounted to even 1 percent of America's total population, by 1930 Jews formed about 3½ percent of America's total population. This dramatic increase in the size of America's Jewish community and the upward mobility of some Jews was accompanied by a resurgence of antisemitism.

In the first half of the 20th century, Jews in the United States faced discrimination in employment, in access to residential and resort areas, in membership in clubs and organizations and in tightened quotas on Jewish enrollment and teaching positions in colleges and universities. Some sources state that the conviction (and later the lynching) of Leo Frank, which turned a spotlight on antisemitism in the United States, also led to the formation of the Anti-Defamation League in October 1913. However, Abraham H. Foxman, the organization's National Director, disputes this claim, stating that American Jews simply needed to found an institution that would combat antisemitism. The social tensions which existed during this period also led to renewed support for the Ku Klux Klan, which had been inactive since 1870.[188][189][190][191]

Antisemitism in the United States reached its peak during the 1920s and 1930s. The pioneering automobile manufacturer Henry Ford propagated antisemitic ideas in his newspaper The Dearborn Independent. The pioneering aviator Charles Lindbergh and many other prominent Americans led the America First Committee in opposing any American involvement in the new war in Europe. However, America First's leaders avoided saying or doing anything that would make them and their organization appear to be antisemitic and for this reason, they voted to drop Henry Ford as an America First member. Lindbergh gave a speech in Des Moines, Iowa in which he expressed the decidedly Ford-like view that: "The three most important groups which have been pressing this country towards war are the British, the Jews, and the Roosevelt Administration."[192] In his diary Lindbergh wrote: "We must limit to a reasonable amount the Jewish influence... Whenever the Jewish percentage of the total population becomes too high, a reaction seems to invariably occur. It is too bad because a few Jews of the right type are, I believe, an asset to any country."[193]

In the late 1930s, the German American Bund held parades which featured Nazi uniforms and flags with swastikas alongside American flags. At Madison Square Garden in 1939, some 20,000 people listened to the Bund leader Fritz Julius Kuhn as he criticized President Franklin Delano Roosevelt by repeatedly referring to him as "Frank D. Rosenfeld" and calling his New Deal the "Jew Deal". Because he espoused a belief in the existence of a Bolshevik–Jewish conspiracy in America, Kuhn and his activities were scrutinized by the US House Committee on Un-American Activities (HUAC) and when the United States entered World War II most of the Bund's members were placed in internment camps, and some of them were deported at the end of the war. Meanwhile, the United States government did not allow the MS St. Louis to enter the United States in 1939 because it was full of Jewish refugees.[194] During race riot in Detroit in 1943, Jewish businesses were targeted for looting and burning.

Eastern Europe after World War II

Antisemitism in the Soviet Union reached a peak in 1948–1953 and culminated in the so-called Doctors' Plot that could have been a precursor to a general purge and a mass deportation of the Soviet Jews as nation. The country's leading Yiddish-writing poets and writers were tortured and executed in a campaign against the so-called rootless cosmopolitans. The excesses largely ended with the death of Soviet leader Joseph Stalin and the de-Stalinization of the Soviet Union. However, the discrimination against Jews had continued, leading to a mass emigration once it was allowed in the 1970s, followed by another during and after the breakup of the Soviet Union, mostly to Israel.

The Kielce pogrom and the Kraków pogrom in communist Poland were examples further incidents of antisemitic attitudes and violence in the Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe. A common theme behind the anti-Jewish violence in the immediate post-war period in Poland were blood libel rumours.[196][197] Poland's later "March events" of 1967–1968 was a state anti-Jewish (officially anti-Zionist) political campaign involving the suppression of the dissident movement and a power struggle within the Polish communist party against the background of the Six-Day War and the Soviet Union's and the Eastern Bloc's new radically anti-Israeli policy in support of socialist Arab countries. Both of these waves of antisemitism in Poland resulted in the emigration of most of the country's Holocaust survivors during the late 1940s and in 1968, mostly to either Israel or the United States.

United States after World War II

During the early 1980s, isolationists on the far right made overtures to anti-war activists on the left in the United States to join forces against government policies in areas where they shared concerns.[198] This was mainly in the area of civil liberties, opposition to United States military intervention overseas and opposition to U.S. support for Israel.[199][200] As they interacted, some of the classic right-wing antisemitic scapegoating conspiracy theories began to seep into progressive circles,[199] including stories about how a "New World Order", also called the "Shadow Government" or "The Octopus",[198] was manipulating world governments. Antisemitic conspiracism was "peddled aggressively" by right-wing groups.[199] Some on the left adopted the rhetoric, which it has been argued, was made possible by their lack of knowledge of the history of fascism and its use of "scapegoating, reductionist and simplistic solutions, demagoguery, and a conspiracy theory of history."[199] The Crown Heights riots of 1991 were a violent expression of tensions within a very poor urban community, pitting African American residents against followers of Hassidic Judaism.

Towards the end of 1990, as the movement against the Gulf War began to build, a number of far-right and antisemitic groups sought out alliances with left-wing anti-war coalitions, who began to speak openly about a "Jewish lobby" that was encouraging the United States to invade the Middle East. This idea evolved into conspiracy theories about a "Zionist-occupied government" (ZOG), which has been seen as equivalent to The Protocols of the Elders of Zion.[198]

The Muslim world

While Islamic antisemitism has increased in the wake of the Arab–Israeli conflict, there were riots against Jews in Middle Eastern countries prior to the foundation of Israel, including unrest in Casablanca,[201] Shiraz and Fez in the 1910s, massacres in Jerusalem, Jaffa and broadly throughout Palestine in the 1920s, pogroms in Algeria, Turkey and Palestine in the 1930s, as well as attacks on the Jews of Iraq and Tunisia in the 1940s. As Palestinian Arab leader Amin al-Husseini decided to make an alliance with Hitler's Germany during World War II, 180 Jews were killed and 700 Jews were injured in the Nazi-inspired riots of 1941 which are known as the Farhud.[202] Jews in the Middle East were also affected by the Holocaust. Most of North Africa came under Nazi control and many Jews were discriminated against and used as slaves until the Axis defeat.[203] In 1945, hundreds of Jews were injured during violent demonstrations in Egypt and Jewish property was vandalized and looted. In November 1945, 130 Jews were killed during a pogrom in Tripoli.[204] In December 1947, shortly after the UN Partition Plan, Arab rioting resulted in hundreds of Jewish casualties in Aleppo, including 75 dead.[205] In Aden, 87 Jews were killed and 120 injured.[206] A mob of Muslim sailors looted Jewish homes and shops in Manama. During 1948 there were further riots against Jews in Tripoli, Cairo, Oujda and Jerada. As the first Arab–Israeli War came to an end in 1949, a grenade attack against the Menarsha Synagogue of Damascus claimed a dozen lives and thirty injured. The 1967 Six-Day War led to further persecution against Jews in the Arab world, prompting an increase in the Jewish exodus that began after Israel was established.[207][208] Over the following years, Jewish population in Arab countries decreased from 856,000 in 1948 to 25,870 in 2009 as a result of emigration, mostly to Israel.[209]

Twenty-first century

The first years of the 21st century have seen an upsurge of antisemitism. Several authors such as Robert S. Wistrich, Phyllis Chesler, and Jonathan Sacks argue that this is antisemitism of a new type stemming from Islamists, which they call new antisemitism.[210][211][212] Blood libel stories have appeared numerous times in the state-sponsored media of a number of Arab nations, on Arab television shows, and on websites.[213][214][215]

In 2004, the United Kingdom set up an all-Parliamentary inquiry into antisemitism, which published its findings in 2006. The inquiry stated that: "Until recently, the prevailing opinion both within the Jewish community and beyond [had been] that antisemitism had receded to the point that it existed only on the margins of society." However, it found a reversal of this progress since 2000 and aimed to investigate the problem, identify the sources of contemporary antisemitism and make recommendations to improve the situation.[216] A 2008 report by the U.S. State Department found that there was an increase in antisemitism across the world, and that both old and new expressions of antisemitism persist.[217] A 2012 report by the U.S. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor also noted a continued global increase in antisemitism, and found that Holocaust denial and opposition to Israeli policy at times was used to promote or justify antisemitism.[218]

Antisemitism in the English-speaking world

William D. Rubenstein, a respected author and historian, outlines the presence of antisemitism in the English-speaking world in one of his essays with the same title. In the essay, he explains that there are relatively low levels of antisemitism in the English-speaking world, particularly in Britain and the United States, because of the values associated with Protestantism, the rise of capitalism, and the establishment of constitutional governments that protect civil liberties. Rubenstein does not argue that the treatment of Jews was ideal in these countries, rather he argues that there has been less overt antisemitism in the English-speaking world due to political, ideological, and social structures. Essentially, English-speaking nations experienced lower levels of antisemitism because their liberal and constitutional frameworks limited the organized, violent expression of antisemitism. In his essay, Rubinstein tries to contextualize the reduction of the Jewish population that led to a period of reduced antisemitism: "All Jews were expelled from England in 1290, the first time Jews had been expelled en masse from a European country".[219]

Protestantism

As mentioned above, Protestantism was a major factor that curbed antisemitism in England beginning in the sixteenth century. This assertion is supported by the fact that the number of reported instances in which Jews were killed in England was significantly higher prior to the birth of Protestantism albeit this was also affected by the number of resident Jews. Protestants were comparatively more understanding of Jews relative to Catholics and other religious groups. One possible reason as to why Protestant groups were more accepting of Jews was the fact that they preferred the Old Testament rather than the New Testament, so their doctrines shared both content and narrative with Jewish teachings. Rubenstein attests that another reason as to why "most of these [Protestants] were predisposed to be sympathetic to the Jews" was because they often "view[ed] themselves, like the biblical Hebrews, as a chosen group that had entered into a direct covenant with God."[219] Lastly, Protestantism's anti-Catholic bend contributed to lower levels of antisemitism: "All of these groups were profoundly hostile to Catholicism. Anti-Catholicism, at both the elite and mass levels, became a key theme in Britain, tending to push antisemitism aside."[219] Overall, the emergence of Protestantism lessened the severity of antisemitism through its use of the Old Testament and its anti-Catholic sentiment.

Capitalism

In post-Napoleonic England, when there was a notable absence of Jews, Britain removed bans on "usury and moneylending,"[219] and Rubenstein attests that London and Liverpool became economic trading hubs which bolstered England's status as an economic powerhouse. Jews were often associated with being the moneymakers and financial bodies in continental Europe, so it is significant that the English were able to claim responsibility for the country's financial growth and not attribute it to Jews. It is also significant that because Jews were not in the spotlight financially, it took a lot of the anger away from them, and as such, antisemitism was somewhat muted in England. It is said that Jews did not rank among the "economic elite of many British cities" in the 19th century.[219] Again, the significance in this is that British Protestants and non-Jews felt less threatened by Jews because they were not imposing on their prosperity and were not responsible for the economic achievements of their nation. Albert Lindemann also proposes in the introduction to his book Antisemitism: A History that Jews "assumed social positions, such as moneylending, that were inherently precarious and tension creating."[220] Lindemann believes that moneylending is inevitably riddled with tension, so as long as Jews were moneylenders, they would always be at the center of the problem and synonymous with fraught financial affairs.

Constitutional government

The third major factor which contributed to the lessening of antisemitism in Britain was the establishment of a constitutional government, something that was later adopted and bolstered in the United States. A constitutional government is one which has a written document that outlines the powers of government in an attempt to balance and protect civil rights. After the English Civil War, the Protectorate (1640–60) and the Glorious Revolution (1688), parliament was established in order to make laws that protected the rights of British citizens.[221] The Bill of Rights specifically outlined laws to protect British civil liberties as well. Thus, it is not surprising that having a constitutional government with liberal principles minimized, to some extent, antisemitism in Britain.

In further attempts to minimize antisemitism within government, the United States' Declaration of Independence embraced the liberal principles that were previously put forth in England and inspired the formation of a republic that had executive, judicial, and legislative powers and even a law that served to "forbid the establishment of any religion or any official religious test for office holding."[222] Having a government that respected and protected civil liberties, especially those pertaining to religious liberties, reduced blatant antisemitism by constitutionally protecting the right to practice different faiths. These sentiments go back to the first President of the United States, George Washington, who asserted his belief in religious inclusion. Rubinstein believes that though instances of antisemitism definitely existed in Britain and America, the moderation of antisemitism was limited in English-Speaking countries largely because of political and social ideologies that come with a constitutional government.