History of gunpowder

Gunpowder is the first explosive to have been developed. Popularly listed as one of the "Four Great Inventions" of China, it was invented during the late Tang dynasty (9th century) while the earliest recorded chemical formula for gunpowder dates to the Song dynasty (11th century). Knowledge of gunpowder spread rapidly throughout Asia and Europe, possibly as a result of the Mongol conquests during the 13th century, with written formulas for it appearing in the Middle East between 1240 and 1280 in a treatise by Hasan al-Rammah, and in Europe by 1267 in the Opus Majus by Roger Bacon. It was employed in warfare to some effect from at least the 10th century in weapons such as fire arrows, bombs, and the fire lance before the appearance of the gun in the 13th century. While the fire lance was eventually supplanted by the gun, other gunpowder weapons such as rockets and fire arrows continued to see use in China, Korea, India, and this eventually led to its use in the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. Bombs too never ceased to develop and continued to progress into the modern day as grenades, mines, and other explosive implements. Gunpowder has also been used for non-military purposes such as fireworks for entertainment, or in explosives for mining and tunneling.

The evolution of guns led to the development of large artillery pieces, popularly known as bombards, during the 15th century, pioneered by states such as the Duchy of Burgundy. Firearms came to dominate early modern warfare in Europe by the 17th century. The gradual improvement of cannons firing heavier rounds for a greater impact against fortifications led to the invention of the star fort and the bastion in the Western world, where traditional city walls and castles were no longer suitable for defense. The use of gunpowder technology also spread throughout the Islamic world and to India, Korea, and Japan. The so-called Gunpowder Empires of the early modern period consisted of the Mughal Empire, Safavid Empire, and Ottoman Empire.

The use of gunpowder in warfare during the course of the 19th century diminished due to the invention of smokeless powder. Gunpowder is often referred to today as "black powder" to distinguish it from the propellant used in contemporary firearms.[1]

Chinese beginnings

Gunpowder formula

Gunpowder was invented in China sometime during the first millennium AD.[2] The earliest possible reference to gunpowder appeared in 142 AD during the Eastern Han dynasty when the alchemist Wei Boyang, also known as the "father of alchemy",[3] wrote about a substance with gunpowder-like properties.[4] He described a mixture of three powders that would "fly and dance" violently in his Cantong qi, otherwise known as the Book of the Kinship of Three, a Taoist text on the subject of alchemy.[5] Although he did not name the powders, "they were almost certainly the ingredients of gunpowder,"[6] and no other explosive known to scientists is composed of three powders.[7] At this time, saltpeter was produced in Hanzhong, but would shift to Gansu and Sichuan later on.[8] Wei Boyang is considered to be a semi-legendary figure meant to represent a "collective unity", and the Cantong qi was probably written in stages from the Han dynasty to 450 AD.[9]

While it was almost certainly not their intention to create a weapon of war, Taoist alchemists continued to play a major role in gunpowder development due to their experiments with sulfur and saltpeter involved in searching for eternal life and ways to transmute one material into another.[10] Historian Peter Lorge notes that despite the early association of gunpowder with Taoism, this may be a quirk of historiography and a result of the better preservation of texts associated with Taoism, rather than being a subject limited to only Taoists.[10] The Taoist quest for the elixir of life attracted many powerful patrons, one of whom was Emperor Wu of Han. One of the resulting alchemical experiments involved heating 10% sulfur and 75% saltpeter to transform them.[7]

The next reference to gunpowder occurred in the year 300 during the Jin dynasty (266–420).[11] A Taoist philosopher by the name of Ge Hong wrote down the ingredients of gunpowder in his surviving works, collectively known as the Baopuzi ("The Master Who Embraces Simplicity"). The "Inner Chapters" (neipian) on Taoism contains records of his experiments to create gold with heated saltpeter, pine resin, and charcoal among other carbon materials, resulting in a purple powder and arsenic vapours.[12] In 492, Taoist alchemists noted that saltpeter, one of the most important ingredients in gunpowder, burns with a purple flame, allowing for practical efforts at purifying the substance.[13] During the Tang dynasty, alchemists used saltpetre in processing the "four yellow drugs" (sulfur, realgar, orpiment, arsenic trisulfide).[14]

The first confirmed reference to what can be considered gunpowder in China occurred more than three hundred years later during the Tang dynasty, first in a formula contained in the Taishang Shengzu Jindan Mijue (太上聖祖金丹秘訣) in 808, and then about 50 years later in a Taoist text known as the Zhenyuan miaodao yaolüe (真元妙道要略).[10][15] The first formula was a combination of six parts sulfur to six parts saltpeter to one part birthwort herb. The Taoist text warned against an assortment of dangerous formulas, one of which corresponds with gunpowder: "Some have heated together sulfur, realgar (arsenic disulfide), and saltpeter with honey; smoke [and flames] result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house burned down."[10] Alchemists called this discovery fire medicine ("huoyao" 火藥), and the term has continued to refer to gunpowder in China into the present day, a reminder of its heritage as a side result in the search for longevity increasing drugs.[16] A book published in 1185 called Gui Dong (The Control of Spirits) also contains a story about a Tang dynasty alchemist whose furnace exploded, but it is not known if this was caused by gunpowder.[17]

The earliest surviving chemical formula of gunpowder dates to 1044[18] in the form of the military manual Wujing Zongyao, also known in English as the Complete Essentials for the Military Classics, which contains a collection of entries on Chinese weaponry.[19][20] However the 1044 edition has since been lost and the only currently extant copy is dated to 1510 during the Ming dynasty.[21] The Wujing Zongyao served as a repository of antiquated or fanciful weaponry, and this applied to gunpowder as well, suggesting that it had already been weaponized long before the invention of what would today be considered conventional firearms. These types of gunpowder weapons styles an assortment of odd names such as "flying incendiary club for subjugating demons", "caltrop fire ball", "ten-thousand fire flying sand magic bomb", "big bees nest", "burning heaven fierce fire unstoppable bomb", "fire bricks" which released "flying swallows", "flying rats", "fire birds", and "fire oxen". Eventually they gave way and coalesced into a smaller number of dominant weapon types, notably gunpowder arrows, bombs, and guns. This was most likely because some weapons were deemed too onerous or ineffective to deploy.[18]

Fire arrows

The early gunpowder formula contained too little saltpeter (about 50%) to be explosive, but the mixture was highly flammable, and contemporary weapons reflected this in their deployment as mainly shock and incendiary weapons. One of the first, if not the first of these weapons was the fire arrow.[22] The first possible reference to the use of fire arrows was by the Southern Wu in 904 during the siege of Yuzhang. An officer under Yang Xingmi by the name of Zheng Fan (鄭璠) ordered his troops to "shoot off a machine to let fire and burn the Longsha Gate", after which he and his troops dashed over the fire into the city and captured it, and he was promoted to Prime Minister Inspectorate for his efforts and the burns his body endured.[23] A later account of this event corroborated with the report and explained that "by let fire (飛火) is meant things like firebombs and fire arrows."[22] Arrows carrying gunpowder were possibly the most applicable form of gunpowder weaponry at the time. Early gunpowder may have only produced an effective flame when exposed to oxygen, thus the rush of air around the arrow in flight would have provided a suitably ample supply of reactants for the reaction.[22]

Rockets

The first fire arrows were arrows strapped with gunpowder incendiaries but they eventually became gunpowder propelled projectiles (rockets). It's not certain when this happened. According to the History of Song, in 969 two Song generals, Yue Yifang and Feng Jisheng (馮繼升), invented a variant fire arrow which used gunpowder tubes as propellants.[24] These fire arrows were shown to the emperor in 970 when the head of a weapons manufacturing bureau sent Feng Jisheng to demonstrate the gunpowder arrow design, for which he was heavily rewarded. However Joseph Needham argues that rockets could not have existed before the 12th century, since the gunpowder formulas listed in the Wujing Zongyao are not suitable as rocket propellant.[25] According to Stephen G. Haw, there is only slight evidence that rockets existed prior to 1200 and it is more likely they were not produced or used for warfare until the latter half of the 13th century.[26] Rockets are recorded to have been used by the Song navy in a military exercise dated to 1245. Internal-combustion rocket propulsion is mentioned in a reference to 1264, recording that the 'ground-rat,' a type of firework, had frightened the Empress-Mother Gongsheng at a feast held in her honor by her son the Emperor Lizong.[27]

In 975, the state of Wuyue sent to the Song dynasty a unit of soldiers skilled in the handling of fire arrows and in the same year, the Song used fire arrows to destroy the fleet of Southern Tang. In 994, the Liao dynasty attacked the Song and laid siege to Zitong with 100,000 troops. They were repelled with the aid of fire arrows.[28] In 1000 a soldier by the name of Tang Fu (唐福) also demonstrated his own designs of gunpowder arrows, gunpowder pots (a proto-bomb which spews fire), and gunpowder caltrops, for which he was richly rewarded as well.[29]

The imperial court took great interest in the progress of gunpowder developments and actively encouraged as well as disseminated military technology. For example, in 1002 a local militia man named Shi Pu (石普) showed his own versions of fireballs and gunpowder arrows to imperial officials. They were so astounded that the emperor and court decreed that a team would be assembled to print the plans and instructions for the new designs to promulgate throughout the realm.[29] The Song court's policy of rewarding military innovators was reported to have "brought about a great number of cases of people presenting technology and techniques" (器械法式) according to the official History of Song.[29] Production of gunpowder and fire arrows heavily increased in the 11th century as the court centralized the production process, constructing large gunpowder production facilities, hiring artisans, carpenters, and tanners for the military production complex in the capital of Kaifeng. One surviving source circa 1023 lists all the artisans working in Kaifeng while another notes that in 1083 the imperial court sent 100,000 gunpowder arrows to one garrison and 250,000 to another.[29]

Evidence of gunpowder in the Liao dynasty and Western Xia is much sparser than in Song, but some evidence such as the Song decree of 1073 that all subjects were henceforth forbidden from trading sulfur and saltpeter across the Liao border, suggests that the Liao were aware of gunpowder developments to the south and coveted gunpowder ingredients of their own.[29]

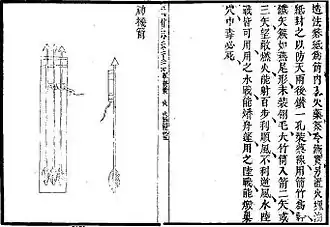

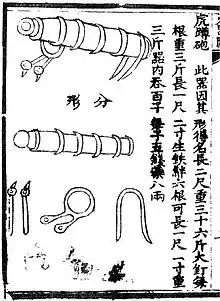

An illustration of fire arrow launchers as depicted in the Wubei Zhi (1621). The launcher is constructed using basketry.

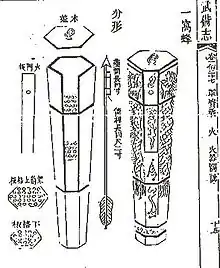

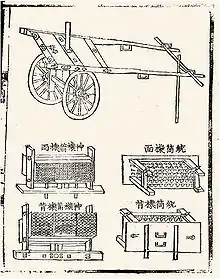

An illustration of fire arrow launchers as depicted in the Wubei Zhi (1621). The launcher is constructed using basketry. A "charging leopard pack" arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi.

A "charging leopard pack" arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. A "nest of bees" or "wasp nest" (yi wo feng 一窩蜂) arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. So called because of its hexagonal honeycomb shape.

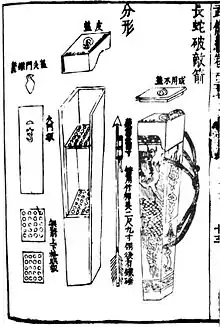

A "nest of bees" or "wasp nest" (yi wo feng 一窩蜂) arrow rocket launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. So called because of its hexagonal honeycomb shape. A "long serpent enemy breaking" fire arrow launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. It carries 32 medium small poisoned rockets and comes with a sling to carry on the back.

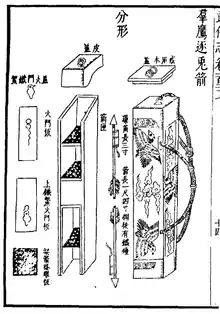

A "long serpent enemy breaking" fire arrow launcher as depicted in the Wubei Zhi. It carries 32 medium small poisoned rockets and comes with a sling to carry on the back. The 'convocation of eagles chasing hare' rocket launcher from the Wubei Zhi. A double-ended rocket pod that carries 30 small poisoned rockets on each end for a total of 60 rockets. It carries a sling for transport.

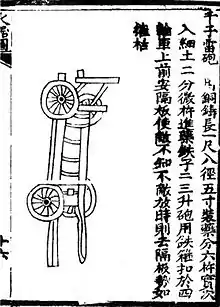

The 'convocation of eagles chasing hare' rocket launcher from the Wubei Zhi. A double-ended rocket pod that carries 30 small poisoned rockets on each end for a total of 60 rockets. It carries a sling for transport. The 'divine fire arrow screen' from the Huolongjing. A stationary arrow launcher that carries one hundred fire arrows. It is activated by a trap-like mechanism, possibly of wheellock design.

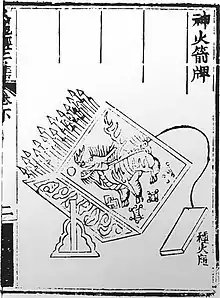

The 'divine fire arrow screen' from the Huolongjing. A stationary arrow launcher that carries one hundred fire arrows. It is activated by a trap-like mechanism, possibly of wheellock design.

Explosives

The Jurchen people of Manchuria united under Wanyan Aguda and established the Jin dynasty in 1115. Allying with the Song, they rose rapidly to the forefront of East Asian powers and defeated the Liao dynasty in a shockingly short span of time, destroying the 150-year balance of power between the Song, Liao, and Western Xia. Remnants of the Liao fled to the west and became known as the Qara Khitai, or Western Liao to the Chinese. In the east, the fragile Song-Jin alliance dissolved once the Jin saw how badly the Song army had performed against Liao forces. Realizing the weakness of Song, the Jin grew tired of waiting and captured all five of the Liao capitals themselves. They proceeded to make war on Song, initiating the Jin-Song Wars.

For the first time, two major powers would have access to equally formidable gunpowder weapons.[30] Initially the Jin expected their campaign in the south to proceed smoothly given how poorly the Song had fared against the Liao. However they were met with stout resistance upon besieging Kaifeng in 1126 and faced the usual array of gunpowder arrows and fire bombs, but also a weapon called the "thunderclap bomb" (霹靂炮), which one witness wrote, "At night the thunderclap bombs were used, hitting the lines of the enemy well, and throwing them into great confusion. Many fled, screaming in fright."[30] The thunderclap bomb was previously mentioned in the Wujing Zongyao, but this was the first recorded instance of its use. Its description in the text reads thus:

The thunderclap bomb contains a length of two or three internodes of dry bamboo with a diameter of 1.5 in. There must be no cracks, and the septa are to be retained to avoid any leakage. Thirty pieces of thin broken porcelain the size of iron coins are mixed with 3 or 4 lb of gunpowder, and packed around the bamboo tube. The tube is wrapped within the ball, but with about an inch or so protruding at each end. A (gun)powder mixture is then applied all over the outer surface of the ball.[31]

Jin troops withdrew with a ransom of Song silk and treasure but returned several months later with their own gunpowder bombs manufactured by captured Song artisans.[30] According to historian Wang Zhaochun, the account of this battle provided the "earliest truly detailed descriptions of the use of gunpowder weapons in warfare."[30] Records show that the Jin used gunpowder arrows and trebuchets to hurl gunpowder bombs while the Song responded with gunpowder arrows, fire bombs, thunderclap bombs, and a new addition called the "molten metal bomb" (金汁炮).[32] As the Jin account describes, when they attacked the city's Xuanhua Gate, their "fire bombs fell like rain, and their arrows were so numerous as to be uncountable."[32] The Jin captured Kaifeng despite the appearance of the molten metal bomb and secured another 20,000 fire arrows for their arsenal.[32]

The molten metal bomb appeared again in 1129 when Song general Li Yanxian (李彥仙) clashed with Jin forces while defending a strategic pass. The Jin assault lasted day and night without respite, using siege carts, fire carts, and sky bridges, but each assault was met with Song soldiers who "resisted at each occasion, and also used molten metal bombs. Wherever the gunpowder touched, everything would disintegrate without a trace."[33]

Fire lance

The Song relocated their capital to Hangzhou and the Jin followed. The fighting that ensued would see the first proto-gun, the fire lance, in action – with earliest confirmed employment by Song dynasty forces against the Jin in 1132 during the siege of De'an (modern Anlu, Hubei),[34][35][36][37] Most Chinese scholars reject the appearance of the fire lance prior to the Jin-Song wars,[32] but its first appearance in art with a silk banner painting from Dunhuang dates to the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period in the mid-10th century.[38]

The siege of De'an marks an important transition and landmark in the history of gunpowder weapons as the fire medicine of the fire lances were described using a new word: "fire bomb medicine" (火炮藥), rather than simply "fire medicine." This could imply the use of a new more potent formula, or simply an acknowledgement of the specialized military application of gunpowder.[37] Peter Lorge suggests that this "bomb powder" may have been corned, making it distinct from normal gunpowder.[39] Evidence of gunpowder firecrackers also points to their appearance at roughly around the same time fire medicine was making its transition in the literary imagination.[40]

Fire lances continued to be used as anti-personnel weapons into the Ming dynasty, and were even attached to battle carts on one situation in 1163. Song commander Wei Sheng constructed several hundred of these carts known as "at-your-desire-war-carts" (如意戰車), which contained fire lances protruding from protective covering on the sides. They were used to defend mobile trebuchets that hurled fire bombs.[37] They were used as cavalry weapons by the 13th century.[41]

Naval bombs

Gunpowder technology also spread to naval warfare and in 1129 Song decreed that all warships were to be fitted with trebuchets for hurling gunpowder bombs.[37] Older gunpowder weapons such as fire arrows were also used. In 1159 a Song fleet of 120 ships caught a Jin fleet at anchor near Shijiu Island (石臼島) off the shore of Shandong peninsula. The Song commander "ordered that gunpowder arrows be shot from all sides, and wherever they struck, flames and smoke rose up in swirls, setting fire to several hundred vessels."[40] Song forces took another victory in 1161 when Song paddle boats ambushed a Jin transport fleet, launched thunderclap bombs, and drowned the Jin force in the Yangtze.[40]

The men inside them paddled fast on the treadmills, and the ships glided forwards as though they were flying, yet no one was visible on board. The enemy thought that they were made of paper. Then all of a sudden a thunderclap bomb was let off: It was made with paper (carton) and filled with lime and sulphur. (Launched from trebuchets) these thunderclap bombs came dropping down from the air, and upon meeting the water exploded with a noise like thunder, the sulphur bursting into flames. The carton case rebounded and broke, scattering the lime to form a smoky fog which blinded the eyes of men and horses so that they could see nothing. Our ships then went forward to attack theirs, and their men and horses were all drowned, so that they were utterly defeated.[42]

— Hai Qiu Fu

According to a minor military official by the name of Zhao Wannian (趙萬年), thunderclap bombs were used again to great effect by the Song during the Jin siege of Xiangyang in 1206–1207. Both sides had gunpowder weapons, but the Jin troops only used gunpowder arrows for destroying the city's moored vessels. The Song used fire arrows, fire bombs, and thunderclap bombs. Fire arrows and bombs were used to destroy Jin trebuchets. The thunderclap bombs were used on Jin soldiers themselves, causing foot soldiers and horsemen to panic and retreat. "We beat our drums and yelled from atop the city wall, and simultaneously fired our thunderclap missiles out from the city walls. The enemy cavalry was terrified and ran away."[43] The Jin were forced to retreat and make camp by the riverside. In a rare occurrence, the Song made a successful offensive on Jin forces and conducted a night assault using boats. They were loaded with gunpowder arrows, thunderclap bombs, a thousand crossbowmen, five hundred infantry, and a hundred drummers. Jin troops were surprised in their encampment while asleep by loud drumming, followed by an onslaught of crossbow bolts, and then thunderclap bombs, which caused a panic of such magnitude that they were unable to even saddle themselves and trampled over each other trying to get away. Two to three thousand Jin troops were slaughtered along with eight to nine hundred horses.[43]

Hard-shell explosives

The introduction of the iron bomb was significant to the history of gunpowder weaponry. Traditionally the inspiration for the development of the iron bomb is ascribed to the tale of a fox hunter named Iron Li. According to the story, around the year 1189 Iron Li developed a new method for hunting foxes which used a ceramic explosive to scare foxes into his nets. The explosive consisted of a ceramic bottle with a mouth, stuffed with gunpowder, and attached with a fuse. Explosive and net were placed at strategic points of places such as watering holes frequented by foxes, and when they got near enough, Iron Li would light the fuse, causing the ceramic bottle to explode and scaring the frightened foxes right into his nets. While a fanciful tale, it's not exactly certain why this would cause the development of the iron bomb, given the explosive was made using ceramics, and other materials such as bamboo or even leather would have done the same job, assuming they made a loud enough noise.[44] Nonetheless, the iron bomb made its first appearance in 1221 at the siege of Qizhou (in modern Hubei), and this time it would be the Jin who possessed the technological advantage. The Song commander Zhao Yurong (趙與褣) survived and was able to relay his account for posterity.

Qizhou was a major fortress city situated near the Yangtze and a 25 thousand strong Jin army advanced on it in 1221. News of the approaching army reached Zhao Yurong in Qizhou, and despite being outnumbered nearly eight to one, he decided to hold the city. Qizhou's arsenal consisted of some three thousand thunderclap bombs, twenty thousand "great leather bombs" (皮大炮), and thousands of gunpowder arrows and gunpowder crossbow bolts. While the formula for gunpowder had become potent enough to consider the Song bombs to be true explosives, they were unable to match the explosive power of the Jin iron bombs. Yurong describes the uneven exchange thus, "The barbaric enemy attacked the Northwest Tower with an unceasing flow of catapult projectiles from thirteen catapults. Each catapult shot was followed by an iron fire bomb [catapult shot], whose sound was like thunder. That day, the city soldiers in facing the catapult shots showed great courage as they maneuvered [our own] catapults, hindered by injuries from the iron fire bombs. Their heads, their eyes, their cheeks were exploded to bits, and only one half [of the face] was left."[45] Jin artillerists were able to successfully target the command center itself: "The enemy fired off catapult stones ... nonstop day and night, and the magistrate's headquarters [帳] at the eastern gate, as well as my own quarters ..., were hit by the most iron fire bombs, to the point that they struck even on top of [my] sleeping quarters and [I] nearly perished! Some said there was a traitor. If not, how would they have known the way to strike at both of these places?"[45]

Zhao was able to examine the new iron bombs himself and described thus, "In shape they are like gourds, but with a small mouth. They are made with pig iron, about two inches thick, and they cause the city's walls to shake."[45] Houses were blown apart, towers battered, and defenders blasted from their placements. Within four weeks all four gates were under heavy bombardment. Finally the Jin made a frontal assault on the walls and scaled them, after which followed a merciless hunt for soldiers, officers, and officials of every level. Zhao managed an escape by clambering over the battlement and making a hasty retreat across the river, but his family remained in the city. Upon returning at a later date to search the ruins, he found that the "bones and skeletons were so mixed up that there was no way to tell who was who."[45]

Hand cannon

.jpg.webp)

The early fire lance, considered to be the ancestor of firearms, is not considered a true gun because it did not include projectiles, whereas a gun by definition uses "the explosive force of the gunpowder to propel a projectile from a tube: cannons, muskets, and pistols are typical examples.".[46][47] Even later on when shrapnel such as ceramics and bits of iron were added to the fire lance, these didn't occlude the barrel, and were only swept along with the discharge rather than making use of windage, and so are referred to as "co-viatives."[33]

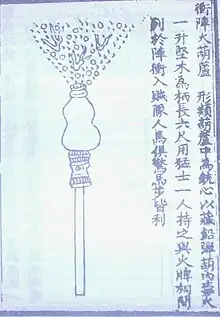

In 1259 a type of "fire-emitting lance" (tuhuoqiang 突火槍) made an appearance and according to the History of Song: "It is made from a large bamboo tube, and inside is stuffed a pellet wad (子窠). Once the fire goes off it completely spews the rear pellet wad forth, and the sound is like a bomb that can be heard for five hundred or more paces."[47][48][49][50][51] The pellet wad mentioned is possibly the first true bullet in recorded history depending on how bullet is defined, as it did occlude the barrel, unlike previous co-viatives used in the fire lance.[47] Fire lances transformed from the "bamboo- (or wood- or paper-) barreled firearm to the metal-barreled firearm"[47] to better withstand the explosive pressure of gunpowder. From there it branched off into several different gunpowder weapons known as "eruptors" in the late 12th and early 13th centuries, with different functions such as the "filling-the-sky erupting tube" which spewed out poisonous gas and porcelain shards, the "orifice-penetrating flying sand magic mist tube" (鑽穴飛砂神霧筒) which spewed forth sand and poisonous chemicals into orifices, and the more conventional "phalanx-charging fire gourd" which shot out lead pellets.[47]

The earliest artistic depiction of what might be a hand cannon – a rock sculpture found among the Dazu Rock Carvings – is dated to 1128, much earlier than any recorded or precisely dated archaeological samples, so it is possible that the concept of a cannon-like firearm has existed since the 12th century.[52] This has been challenged by others such as Liu Xu, Cheng Dong, and Benjamin Avichai Katz Sinvany. According to Liu, the weight of the cannon would have been too much for one person to hold, especially with just one arm, and points out that fire lances were being used a decade later at De'an. Cheng Dong believes that the figure depicted is actually a wind spirit letting air out of a bag rather than a cannon emitting a blast. Stephen Haw also considered the possibility that the item in question was a bag of air but concludes that it is a cannon because it was grouped with other weapon wielding sculptures. Sinvany believes in the wind bag interpretation and that the cannonball indentation was added later on.[53]

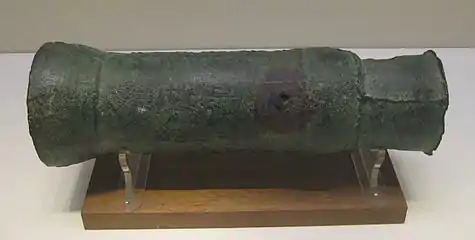

Archaeological samples of the gun, specifically the hand cannon (huochong), have been dated starting from the 13th century. The oldest extant gun whose dating is unequivocal is the Xanadu Gun because it contains an inscription describing its date of manufacture corresponding to 1298. It is so called because it was discovered in the ruins of Xanadu, the Mongol summer palace in Inner Mongolia. The Xanadu Gun is 34.7 cm in length and weighs 6.2 kg. The design of the gun includes axial holes in its rear which some speculate could have been used in a mounting mechanism. Like most early guns it is small, weighing just over six kilograms and thirty-five centimeters in length.[54] Although the Xanadu Gun is the most precisely dated gun from the 13th century, other extant samples with approximate dating likely predate it. The Heilongjiang hand cannon is dated a decade earlier to 1288, but the dating method is based on contextual evidence; the gun bears no inscription or era date.[55] According to the History of Yuan, in 1287, a group of soldiers equipped with hand cannons led by the Jurchen commander Li Ting (李庭) attacked the rebel prince Nayan's camp. The History reports that the hand cannons not only "caused great damage," but also caused "such confusion that the enemy soldiers attacked and killed each other."[56] The hand cannons were used again in the beginning of 1288. Li Ting's "gun-soldiers" or chongzu (銃卒) were able to carry the hand cannons "on their backs". The passage on the 1288 battle is also the first to coin the name chong (銃) for metal-barrel firearms. Chong was used instead of the earlier and more ambiguous term huo tong (fire tube; 火筒), which may refer to the tubes of fire lances, proto-cannons, or signal flares.[57]

Another specimen, the Wuwei Bronze Cannon, was discovered in 1980 and may possibly be the oldest as well as largest cannon of the 13th century: a 100 centimeter 108 kilogram bronze cannon discovered in a cellar in Wuwei, Gansu containing no inscription, but has been dated by historians to the late Western Xia period between 1214 and 1227. The gun contained an iron ball about nine centimeters in diameter, which is smaller than the muzzle diameter at twelve centimeters, and 0.1 kilograms of gunpowder in it when discovered, meaning that the projectile might have been another co-viative.[58] Ben Sinvany and Dang Shoushan believe that the ball used to be much larger prior to its highly corroded state at the time of discovery.[59] While large in size, the weapon is noticeably more primitive than later Yuan dynasty guns, and is unevenly cast. A similar weapon was discovered not far from the discovery site in 1997, but much smaller in size at only 1.5 kg.[60] Chen Bingying disputes this however, and argues there were no guns before 1259, while Dang Shoushan believes the Western Xia guns point to the appearance of guns by 1220, and Stephen Haw goes even further by stating that guns were developed as early as 1200.[61] Sinologist Joseph Needham and renaissance siege expert Thomas Arnold provide a more conservative estimate of around 1280 for the appearance of the "true" cannon.[62][63]

Whether or not any of these are correct, it seems likely that the gun was born sometime during the 13th century.[60]

Use by the Mongols

.jpg.webp)

The Mongols and their rise in world history as well as conflicts with both the Jin and Song played a key role in the evolution of gunpowder technology.[64] Mongol aptitude in incorporating foreign experts extended to the Chinese, who provided artisans that followed Mongol armies willingly and unwillingly far into the west and even east, to Japan. Unfortunately textual evidence for this is scant as the Mongols left few documents. This lack of primary source documents has caused some historians and scholars such as Kate Raphael to doubt the Mongol's role in disseminating gunpowder throughout Eurasia. On the opposite side stand historians such as Tonio Andrade and Stephen Haw, who believe that the Mongol Empire not only used gunpowder weapons but deserves the moniker "the first gunpowder empire."[65]

Conquest of the Jin dynasty

The first concerted Mongol invasion of Jin occurred in 1211 and total conquest was not accomplished until 1234. In 1232 the Mongols besieged the Jin capital of Kaifeng and deployed gunpowder weapons along with other more conventional siege techniques such as building stockades, watchtowers, trenches, guardhouses, and forcing Chinese captives to haul supplies and fill moats.[66] Jin scholar Liu Qi (劉祈) recounts in his memoir, "the attack against the city walls grew increasingly intense, and bombs rained down as [the enemy] advanced."[66] The Jin defenders also deployed gunpowder bombs as well as fire arrows (huo jian 火箭) launched using a type of early solid-propellant rocket.[24] Of the bombs, Liu Qi writes, "From within the walls the defenders responded with a gunpowder bomb called the heaven-shaking-thunder bomb (震天雷). Whenever the [Mongol] troops encountered one, several men at a time would be turned into ashes."[66]

A more fact based and clear description of the bomb exists in the History of Jin: "The heaven-shaking-thunder bomb is an iron vessel filled with gunpowder. When lighted with fire and shot off, it goes off like a crash of thunder that can be heard for a hundred li [thirty miles], burning an expanse of land more than half a mu [所爇圍半畝之上, a mu is a sixth of an acre], and the fire can even penetrate iron armor."[66] A Ming official named He Mengchuan would encounter an old cache of these bombs three centuries later in the Xi'an area: "When I went on official business to Shaanxi Province, I saw on top of Xi'an's city walls an old stockpile of iron bombs. They were called 'heaven-shaking-thunder' bombs, and they were like an enclosed rice bowl with a hole at the top, just big enough to put your finger in. The troops said they hadn't been used for a very long time."[66] Furthermore, he wrote, "When the powder goes off, the bomb rips open, and the iron pieces fly in all directions. That is how it is able to kill people and horses from far away."[67]

Heaven-shaking-thunder bombs, also known as thunder crash bombs, were used prior to the siege in 1231 when a Jin general made use of them in destroying a Mongol warship, but during the siege the Mongols responded by protecting themselves with elaborate screens of thick cowhide. This was effective enough for workers to get right up to the walls to undermine their foundations and excavate protective niches. Jin defenders countered by tying iron cords and attaching them to heaven-shaking-thunder bombs, which were lowered down the walls until they reached the place where the miners worked. The protective leather screens were unable to withstand the explosion, and were penetrated, killing the excavators.[67]

Another weapon the Jin employed was an improved version of the fire lance called the flying fire lance. The History of Jin provides a detailed description: "To make the lance, use chi-huang paper, sixteen layers of it for the tube, and make it a bit longer than two feet. Stuff it with willow charcoal, iron fragments, magnet ends, sulfur, white arsenic [probably an error that should mean saltpeter], and other ingredients, and put a fuse to the end. Each troop has hanging on him a little iron pot to keep fire [probably hot coals], and when it's time to do battle, the flames shoot out the front of the lance more than ten feet, and when the gunpowder is depleted, the tube isn't destroyed."[67] While Mongol soldiers typically held a view of disdain toward most Jin weapons, apparently they greatly feared the flying fire lance and heaven-shaking-thunder bomb.[66] Kaifeng managed to hold out for a year before the Jin emperor fled and the city capitulated. In some cases Jin troops still fought with some success, scoring isolated victories such as when a Jin commander led 450 fire lancers against a Mongol encampment, which was "completely routed, and three thousand five hundred were drowned."[67] Even after the Jin emperor committed suicide in 1234, one loyalist gathered all the metal he could find in the city he was defending, even gold and silver, and made explosives to lob against the Mongols, but the momentum of the Mongol Empire could not be stopped.[68] By 1234, both the Western Xia and Jin dynasty had been conquered.[69]

Conquest of the Song dynasty

The Mongol war machine moved south and in 1237 attacked the Song city of Anfeng (modern Shouxian, Anhui) "using gunpowder bombs [huo pao] to burn the [defensive] towers."[69] These bombs were apparently quite large. "Several hundred men hurled one bomb, and if it hit the tower it would immediately smash it to pieces."[69] The Song defenders under commander Du Gao (杜杲) rebuilt the towers and retaliated with their own bombs, which they called the "Elipao," after a famous local pear, probably in reference to the shape of the weapon.[69] Perhaps as another point of military interest, the account of this battle also mentions that the Anfeng defenders were equipped with a type of small arrow to shoot through eye slits of Mongol armor, as normal arrows were too thick to penetrate.[69]

By the mid 13th century, gunpowder weapons had become central to the Song war effort. In 1257 the Song official Li Zengbo was dispatched to inspect frontier city arsenals. Li considered an ideal city arsenal to include several hundred thousand iron bombshells, and also its own production facility to produce at least a couple thousand a month. The results of his tour of the border were severely disappointing and in one arsenal he found "no more than 85 iron bomb-shells, large and small, 95 fire-arrows, and 105 fire-lances. This is not sufficient for a mere hundred men, let alone a thousand, to use against an attack by the ... barbarians. The government supposedly wants to make preparations for the defense of its fortified cities, and to furnish them with military supplies against the enemy (yet this is all they give us). What chilling indifference!"[70] Fortunately for the Song, Möngke Khan died in 1259 and the war would not continue until 1269 under the leadership of Kublai Khan, but when it did the Mongols came in full force.

Blocking the Mongols' passage south of the Yangtze were the twin fortress cities of Xiangyang and Fancheng. What resulted was one of the longest sieges the world had ever known, lasting from 1268 to 1273. In 1273 the Mongols enlisted the expertise of two Muslim engineers, one from Persia and one from Syria, who helped in the construction of counterweight trebuchets. These new siege weapons had the capability of throwing larger missiles further than the previous traction trebuchets. One account records, "when the machinery went off the noise shook heaven and earth; every thing that [the missile] hit was broken and destroyed."[71] The fortress city of Xiangyang fell in 1273.[33]

The next major battle to feature gunpowder weapons was during a campaign led by the Mongol general Bayan, who commanded an army of around two hundred thousand, consisting of mostly Chinese soldiers. It was probably the largest army the Mongols had ever used. Such an army was still unable to successfully storm Song city walls, as seen in the 1274 Siege of Shayang. Thus Bayan waited for the wind to change to a northerly course before ordering his artillerists to begin bombarding the city with molten metal bombs, which caused such a fire that "the buildings were burned up and the smoke and flames rose up to heaven."[33] Shayang was captured and its inhabitants massacred.[33]

Gunpowder bombs were used again in the 1275 Siege of Changzhou in the latter stages of the Mongol-Song Wars. Upon arriving at the city, Bayan gave the inhabitants an ultimatum: "if you ... resist us ... we shall drain your carcasses of blood and use them for pillows."[33] This didn't work and the city resisted anyway, so the Mongol army bombarded them with fire bombs before storming the walls, after which followed an immense slaughter claiming the lives of a quarter million.[33] The war lasted for only another four years during which some remnants of the Song held up last desperate defenses. In 1277, 250 defenders under Lou Qianxia conducted a suicide bombing and set off a huge iron bomb when it became clear defeat was imminent. Of this, the History of Song writes, "the noise was like a tremendous thunderclap, shaking the walls and ground, and the smoke filled up the heavens outside. Many of the troops [outside] were startled to death. When the fire was extinguished they went in to see. There were just ashes, not a trace left."[72][73] So came an end to the Mongol-Song Wars, which saw the deployment of all the gunpowder weapons available to both sides at the time, which for the most part meant gunpowder arrows, bombs, and lances, but in retrospect, another development would overshadow them all, the birth of the gun.[47]

In 1280, a large store of gunpowder at Weiyang in Yangzhou accidentally caught fire, producing such a massive explosion that a team of inspectors at the site a week later deduced that some 100 guards had been killed instantly, with wooden beams and pillars blown sky high and landing at a distance of over 10 li (~2 mi. or ~3 km) away from the explosion, creating a crater more than ten feet deep.[74]

By the time of Jiao Yu and his Huolongjing (a book that describes military applications of gunpowder in great detail) in the mid 14th century, the explosive potential of gunpowder was perfected, as the level of nitrate in gunpowder formulas had risen from a range of 12% to 91%,[75] with at least 6 different formulas in use that are considered to have maximum explosive potential for gunpowder.[75] By that time, the Chinese had discovered how to create explosive round shot by packing their hollow shells with this nitrate-enhanced gunpowder.[76]

Invasions of Europe and Japan

Gunpowder may have been used during the Mongol invasions of Europe.[77] "Fire catapults", "pao", and "naphtha-shooters" are mentioned in some sources.[78][79][80][81] However, according to Timothy May, "there is no concrete evidence that the Mongols used gunpowder weapons on a regular basis outside of China."[82]

Shortly after the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274–1281), the Japanese produced a scroll painting depicting a bomb. Called tetsuhau in Japanese, the bomb is speculated to have been the Chinese thunder crash bomb.[83] Japanese descriptions of the invasions also talk of iron and bamboo pao causing "light and fire" and emitting 2–3,000 iron bullets.[84] The Nihon Kokujokushi, written around 1300, mentions huo tong (fire tubes) at the Battle of Tsushima in 1274 and the second coastal assault led by Holdon in 1281. The Hachiman Gudoukun of 1360 mentions iron pao "which caused a flash of light and a loud noise when fired."[85] The Taiheki of 1370 mentions "iron pao shaped like a bell."[85]

The commanding general kept his position on high ground, and directed the various detachments as need be with signals from hand-drums. But whenever the (Mongol) soldiers took to flight, they sent iron bomb-shells (tetsuho) flying against us, which made our side dizzy and confused. Our soldiers were frightened out of their wits by the thundering explosions; their eyes were blinded, their ears deafened, so that they could hardly distinguish east from west. According to our manner of fighting, we must first call out by name someone from the enemy ranks, and then attack in single combat. But they (the Mongols) took no notice at all of such conventions; they rushed forward all together in a mass, grappling with any individuals they could catch and killing them.[86]

— Hachiman Gudoukun

Historiography of gunpowder and gun transmission

According to historian Tonio Andrade, "Scholars today overwhelmingly concur that the gun was invented in China,"[87] however multiple independent gunpowder and gun invention theories continue to exist today, advocating for European, Islamic, or Indian origins. Opponents of Chinese invention and transmission criticize the vagueness of Chinese records on specific gunpowder usage in weaponry, the possible lack of gunpowder in incendiary weapons as described by Chinese documents, the weakness of Chinese firearms, the lack of evidence of guns between Europe and China before 1326, and emphasize the appearance of earlier or superior gunpowder weapons.[88] For example, Stephen Morillo, Jeremy Black, and Paul Lococo's War in World History argues that "the sources are not entirely clear about Chinese use of gunpowder in guns. There are references to bamboo and iron cannons, or perhaps proto-cannons, but these seem to have been small, unreliable, handheld weapons in this period. The Chinese do seem to have invented guns independently of the Europeans, at least in principle; but, in terms of effective cannon, the edge goes to Europe."[89] Independent invention theories include examples such as the attribution of gunpowder to Berthold Schwarz (Black Berthold),[24] the usage of cannons by Mamluks at the Battle of Ain Jalut in 1260,[90] and descriptions of gunpowder and firearms to various Sanskrit texts.[91] The problem with all theories of non-Chinese invention boils down to lack of evidence and dating. It's not certain who exactly Berthold Schwarz was since there are no contemporary records of him. According to J.R. Partington, Black Berthold is a purely legendary figure invented for the purpose of providing a German origin for gunpowder and cannon.[92] The source for Mamluk usage of cannons in the Battle of Ain Jalut is a text dated to the late 14th century.[93][94] The dating of the cited Sanskrit texts is often dubious at best, with one example, Sukraniti, containing descriptions of a musket and a cart-drawn gun.[95]

Proponents of Chinese invention and transmission point out the acute dearth of any significant evidence of evolution or experimentation with gunpowder or gunpowder weapons leading up to the gun outside of China.[96] Gunpowder appeared in Europe primed for military usage as an explosive and propellant, bypassing a process which took centuries of Chinese experimentation with gunpowder weaponry to reach, making a nearly instantaneous and seamless transition into firearm warfare, as its name suggests. Furthermore, early European gunpowder recipes shared identical defects with Chinese recipes such as the inclusion of the poisons sal ammoniac and arsenic, which provide no benefit to gunpowder.[97] Bert S. Hall explains this phenomenon in his Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe: Gunpowder, Technology, and Tactics by drawing upon the gunpowder transmission theory, explaining that "gunpowder came [to Europe], not as an ancient mystery, but as a well-developed modern technology, in a manner very much like twentieth-century 'technology-transfer' projects."[98] In a similar vein, Peter Lorge supposes that the Europeans experienced gunpowder "free from preconceived notions of what could be done," in contrast to China, "where a wide range of formulas and a broad variety of weapons demonstrated the full range of possibilities and limitations of the technologies involved."[99] There is also the vestige of Chinese influence on Muslim terminology of key gunpowder related items such as saltpeter, which has been described as either Chinese snow or salt, fireworks which were called Chinese flowers, and rockets which were called Chinese arrows.[88] Moreover, Europeans in particular experienced great difficulty in obtaining saltpeter, a primary ingredient of gunpowder which was relatively scarce in Europe compared to China, and had to be obtained from "distant lands or extracted at high cost from soil rich in dung and urine."[100] Thomas Arnold believes that the similarities between early European cannons and contemporary Chinese models suggests a direct transmission of cannon making knowledge from China rather than a home grown development.[101]

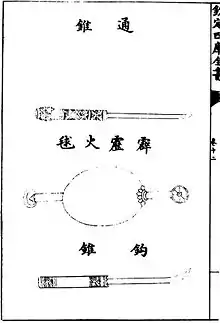

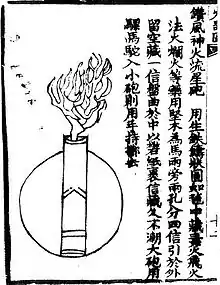

An "eruptor" as depicted in the Huolongjing. Essentially a fire lance on a frame, the 'multiple bullets magazine eruptor' shoots lead shots, which are loaded in a magazine and fed into the barrel when turned around on its axis.

An "eruptor" as depicted in the Huolongjing. Essentially a fire lance on a frame, the 'multiple bullets magazine eruptor' shoots lead shots, which are loaded in a magazine and fed into the barrel when turned around on its axis. An illustration of a 'flying-cloud thunderclap-eruptor,' a cannon firing thunderclap bombs, from the Huolongjing.

An illustration of a 'flying-cloud thunderclap-eruptor,' a cannon firing thunderclap bombs, from the Huolongjing. A 'poison fog divine smoke eruptor' (du wu shen yan pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. Small shells emitting poisonous smoke are fired.

A 'poison fog divine smoke eruptor' (du wu shen yan pao) as depicted in the Huolongjing. Small shells emitting poisonous smoke are fired. Cannon and cannon-shooters from the page from About the Secrets of Secrets manuscript by Pseudo-Aristotle, 1320s

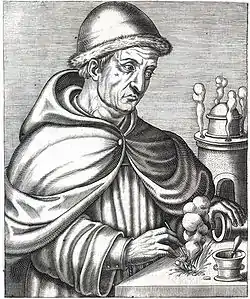

Cannon and cannon-shooters from the page from About the Secrets of Secrets manuscript by Pseudo-Aristotle, 1320s Portrait identifying Schwarz as the "inventor of artillery"

Portrait identifying Schwarz as the "inventor of artillery"

Spread throughout Eurasia and Africa

Middle East

The Muslim world acquired the gunpowder formula some time after 1240, but before 1280, by which time Hasan al-Rammah had written, in Arabic, recipes for gunpowder, instructions for the purification of saltpeter, and descriptions of gunpowder incendiaries. Early Muslim sources suggest that knowledge of gunpowder was acquired from China and may have been introduced by invading Mongols.[104] This is implied by al-Rammah's usage of "terms that suggested he derived his knowledge from Chinese sources."[105] Early Arab texts on gunpowder refer to saltpeter as "Chinese snow" (Arabic: ثلج الصين thalj al-ṣīn), fireworks as "Chinese flowers" and rockets as "Chinese arrows" (sahm al-Khitai).[105] Similarly, the Persians called saltpeter "Chinese salt"[106][107][108] or "salt from Chinese salt marshes" (namak shūra chīnī Persian: نمک شوره چيني).[109][110] Fireworks listed by al-Rammah include "wheels of China" and "flowers of China".[111]

The gunpowder formula of al-Rammah has a saltpetre content of 68% to 75%, which is too high for rocketry but suitable for explosives, however no explosives are mentioned.[112][113] Al-Rammah's text, The Book of Military Horsemanship and Ingenious War Devices (Kitab al-Furusiya wa'l-Munasab al-Harbiya), does however mention fuses, incendiary bombs, naphtha pots, fire lances, and an illustration and description of the earliest torpedo. The torpedo was called the "egg which moves itself and burns."[113] Two iron sheets were fastened together and tightened using felt. The flattened pear shaped vessel was filled with gunpowder, metal filings, "good mixtures," two rods, and a large rocket for propulsion. Judging by the illustration, it was evidently supposed to glide across the water.[113][114][115]

Hasan al-Rammah was the first Muslim to describe the purification of saltpeter[116] using the chemical processes of solution and crystallization. This was the first clear method for the purification of saltpeter.[117]

According to Joseph Needham, fire lances were used in battles between the Muslims and Mongols in 1299 and 1303.[118]

The earliest surviving documentary evidence for cannons in the Islamic world is from an Arabic manuscript dated to the early 14th century.[119][120] The author's name is uncertain but may have been Shams al-Din Muhammad, who died in 1350.[113] Dating from around 1320–1350, the illustrations show gunpowder weapons such as gunpowder arrows, bombs, fire tubes, and fire lances or proto-guns.[115] The manuscript describes a type of gunpowder weapon called a midfa which uses gunpowder to shoot projectiles out of a tube at the end of a stock.[121] Some consider this to be a cannon while others do not. The problem with identifying cannons in early 14th century Arabic texts is the term midfa, which appears from 1342 to 1352 but cannot be proven to be true hand-guns or bombards. Contemporary accounts of a metal-barrel cannon in the Islamic world do not occur until 1365.[122] Needham believes that in its original form the term midfa refers to the tube or cylinder of a naphtha projector (flamethrower), then after the invention of gunpowder it meant the tube of fire lances, and eventually it applied to the cylinder of hand-gun and cannon.[123]

Description of the drug (mixture) to be introduced in the madfa'a (cannon) with its proportions: barud, ten; charcoal two drachmes, sulphur one and a half drachmes. Reduce the whole into a thin powder and fill with it one third of the madfa'a. Do not put more because it might explode. This is why you should go to the turner and ask him to make a wooden madfa'a whose size must be in proportion with its muzzle. Introduce the mixture (drug) strongly; add the bunduk (balls) or the arrow and put fire to the priming. The madfa'a length must be in proportion with the hole. If the madfa'a was deeper than the muzzle's width, this would be a defect. Take care of the gunners. Be careful[113]

— Rzevuski MS, possibly written by Shams al-Din Muhammad, c. 1320–1350

According to Paul E. J. Hammer, the Mamluks certainly used cannons by 1342.[124] According to J. Lavin, cannons were used by Moors at the siege of Algeciras in 1343. A metal cannon firing an iron ball was described by Shihab al-Din Abu al-Abbas al-Qalqashandi between 1365 and 1376.[122]

Europe

A common theory of how gunpowder came to Europe is that it made its way along the Silk Road through the Middle East. Another is that it was brought to Europe during the Mongol invasion in the first half of the 13th century.[125][96] Some sources claim that Chinese firearms and gunpowder weapons may have been deployed by Mongols against European forces at the Battle of Mohi in 1241.[126][127] It may also have been due to subsequent diplomatic and military contacts. Some authors have speculated that William of Rubruck, who served as an ambassador to the Mongols from 1253 to 1255, was a possible intermediary in the transmission of gunpowder. His travels were recorded by Roger Bacon,[128] who was the first European to mention gunpowder, but the records of William's journey do not contain any mention of gunpowder.[96][129]

The earliest European references to gunpowder are found in Roger Bacon's Opus Majus from 1267, in which he mentions a firecracker toy found in various parts of the world.[96][130] The passage reads: "We have an example of these things (that act on the senses) in [the sound and fire of] that children's toy which is made in many [diverse] parts of the world; i.e., a device no bigger than one's thumb. From the violence of that salt called saltpeter [together with sulfur and willow charcoal, combined into a powder] so horrible a sound is made by the bursting of a thing so small, no more than a bit of parchment [containing it], that we find [the ear assaulted by a noise] exceeding the roar of strong thunder, and a flash brighter than the most brilliant lightning."[131] In the early 20th century, British artillery officer Henry William Lovett Hime proposed that another work tentatively attributed to Bacon, Epistola de Secretis Operibus Artis et Naturae, et de Nullitate Magiae contained an encrypted formula for gunpowder. This claim has been disputed by historians of science including Lynn Thorndike, John Maxson Stillman and George Sarton and by Bacon's editor Robert Steele, both in terms of authenticity of the work, and with respect to the decryption method.[131] In any case, the formula claimed to have been decrypted (7:5:5 saltpeter:charcoal:sulfur) is not useful for firearms use or even firecrackers, burning slowly and producing mostly smoke.[132][133] However, if Bacon's recipe is taken as measurements by volume rather than weight, a far more potent and serviceable explosive powder is created suitable for firing hand-cannons, albeit less consistent due to the inherent inaccuracies of measurements by volume. One example of this composition resulted in 100 parts saltpeter, 27 parts charcoal, and 45 parts sulfur, by weight.[134]

The oldest written recipes for gunpowder in Europe were recorded under the name Marcus Graecus or Mark the Greek between 1280 and 1300 in the Liber Ignium, or Book of Fires.[135] One recipe for "flying fire" (ignis volatilis) involves saltpeter, sulfur, and colophonium, which, when inserted into a reed or hollow wood, "flies away suddenly and burns up everything." Another recipe, for artificial "thunder", specifies a mixture of one pound native sulfur, two pounds linden or willow charcoal, and six pounds of saltpeter. Another specifies a 1:3:9 ratio.[136]

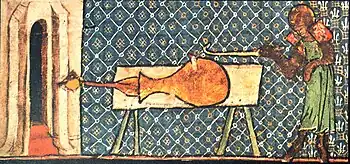

The earliest known European depiction of a gun appeared in 1326 in a manuscript by Walter de Milemete, although not necessarily drawn by him, known as De Nobilitatibus, sapientii et prudentiis regum (Concerning the Majesty, Wisdom, and Prudence of Kings), which displays a gun with a large arrow emerging from it and its user lowering a long stick to ignite the gun through the touchole[137][98] In the same year, another similar illustration showed a darker gun being set off by a group of knights, which also featured in another work of de Milemete's, De secretis secretorum Aristotelis.[138] On 11 February of that same year, the Signoria of Florence appointed two officers to obtain canones de mettallo and ammunition for the town's defense.[139] In the following year a document from the Turin area recorded a certain amount was paid "for the making of a certain instrument or device made by Friar Marcello for the projection of pellets of lead."[98] The bronze vase-shaped gun from Mantua, unfortunately disappeared in 1849, but of which we have drawings and measurements taken in 1786, dates back to 1322. It was 16.4 cm long, weighed about 5 kg and had a caliber of 5.5 cm.[140]

The 1320s seem to have been the takeoff point for guns in Europe according to most modern military historians. Scholars suggest that the lack of gunpowder weapons in a well-traveled Venetian's catalogue for a new crusade in 1321 implies that guns were unknown in Europe up until this point.[98] From the 1320s guns spread rapidly across Europe. The French raiding party that sacked and burned Southampton in 1338 brought with them a ribaudequin and 48 bolts (but only 3 pounds of gunpowder).[141] By 1341 the town of Lille had a "tonnoire master," and a tonnoire was an arrow-hurling gun. In 1345, two iron cannons were present in Toulouse. In 1346 Aix-la-Chapelle too possessed iron cannons which shot arrows (busa ferrea ad sagittandum tonitrum).[142] The Battle of Crécy in 1346 was one of the first in Europe where cannons were used.[143] By 1350 Petrarch wrote that the presence of cannons on the battlefield was 'as common and familiar as other kinds of arms'.[144]

Around the late 14th century European and Ottoman guns began to deviate in purpose and design from guns in China, changing from small anti-personnel and incendiary devices to the larger artillery pieces most people imagine today when using the word "cannon."[145] If the 1320s can be considered the arrival of the gun on the European scene, then the end of the 14th century may very well be the departure point from the trajectory of gun development in China. In the last quarter of the 14th century, European guns grew larger and began to blast down fortifications.[145]

.jpg.webp) Vase-shaped gun of Mantua (image produced 1869), no longer extant

Vase-shaped gun of Mantua (image produced 1869), no longer extant Oldest known European depiction of a firearm from De Nobilitatibus Sapientii Et Prudentiis Regum by Walter de Milemete (1326).

Oldest known European depiction of a firearm from De Nobilitatibus Sapientii Et Prudentiis Regum by Walter de Milemete (1326). Reconstruction of an arrow-firing cannon that appears in a 1326 manuscript.

Reconstruction of an arrow-firing cannon that appears in a 1326 manuscript. Western European handgun, 1380. 18 cm-long and weighing 1.04 kg, it was fixed to a wooden pole to facilitate manipulation. Musée de l'Armée.

Western European handgun, 1380. 18 cm-long and weighing 1.04 kg, it was fixed to a wooden pole to facilitate manipulation. Musée de l'Armée. The Mörkö gun is another early Swedish firearm discovered by a fisherman in the Baltic Sea at the coast of Södermansland near Nynäs in 1828. It has been given a date of c. 1390.

The Mörkö gun is another early Swedish firearm discovered by a fisherman in the Baltic Sea at the coast of Södermansland near Nynäs in 1828. It has been given a date of c. 1390. The Tannenberg handgonne is a cast bronze firearm. Muzzle bore 15–16 mm. Found in the water well of the 1399 destroyed Tannenberg castle. Oldest surviving firearm from Germany.

The Tannenberg handgonne is a cast bronze firearm. Muzzle bore 15–16 mm. Found in the water well of the 1399 destroyed Tannenberg castle. Oldest surviving firearm from Germany.

Southeast Asia

In Southeast Asia, cannons were used by the Ayutthaya Kingdom in 1352 during its invasion of the Khmer Empire.[146] Within a decade large quantities of gunpowder could be found in the Khmer Empire.[146] By the end of the century firearms were also used by the Trần dynasty in Đại Việt.[147]

The Mongol invasion of Java in 1293 brought gunpowder technology to the Nusantara archipelago in the form of cannon (Chinese: 炮—Pào). The knowledge of making gunpowder-based weapon has been known after the failed Mongol invasion of Java.[148]: 1–2 [149][150]: 220 The predecessor of firearms, the pole gun (bedil tombak), was recorded as being used in Java by 1413,[151][152]: 245 while the knowledge of making "true" firearms came much later, after the middle of 15th century. It was brought by the Muslim traders from West Asia, most probably the Arabs. The precise year of introduction is unknown, but it may be safely concluded to be no earlier than 1460.[153]: 23

Portuguese influence to local weaponry after the capture of Malacca (1511) resulted in a new type of hybrid tradition matchlock firearm, the istinggar.[154][155]: 53 Saltpeter harvesting was recorded by Dutch and German travelers as being common in even the smallest villages and was collected from the decomposition process of large dung hills specifically piled for this purpose. The Dutch punishment for possession of non-permitted gunpowder appears to have been amputation.[156]: 180–181 Ownership and manufacture of gunpowder was later prohibited by the colonial Dutch occupiers.[157] According to colonel McKenzie quoted in the book The History of Java (1817) by Thomas Stamford Raffles, the purest sulfur was supplied from a crater from a mountain near the straits of Bali.[156]: 180–181

India

Gunpowder technology is believed to have arrived in India by the mid-14th century, but could have been introduced much earlier by the Mongols, who had conquered both China and some borderlands of India, perhaps as early as the mid-13th century. The unification of a large single Mongol Empire resulted in the free transmission of Chinese technology into Mongol conquered parts of India. Regardless, it is believed that the Mongols used Chinese gunpowder weapons during their invasions of India.[158] It was written in the Tarikh-i Firishta (1606–1607) that the envoy of the Mongol ruler Hulegu Khan was presented with a dazzling pyrotechnics display upon his arrival in Delhi in 1258.[159] The first gunpowder device, as opposed to naphtha-based pyrotechnics, introduced to India from China in the second half of the 13th century, was a rocket called the "hawai" (also called "ban").[160] The rocket was used as an instrument of war from the second half of the 14th century onward,[160] and the Delhi sultanate as well as the Bahmani Sultanate made good use of them.[161] As a part of an embassy to India by Timurid leader Shah Rukh (1405–1447), 'Abd al-Razzaq mentioned naphtha-throwers mounted on elephants and a variety of pyrotechnics put on display.[162] Roger Pauly has written that "while gunpowder was primarily a Chinese innovation," the saltpeter that led to the invention of gunpowder may have arrived from India, although it is also likely that it originated indigenously in China.[163]

Firearms known as top-o-tufak also existed in the Vijayanagara Empire of Southern India by as early as 1366.[159] In 1368–1369, the Bahmani Sultanate may have used firearms against Vijayanagara, but these weapons could have been pyrotechnics as well.[164] By 1442 guns had a clearly felt presence in India as attested to by historical records.[87] From then on the employment of gunpowder warfare in India was prevalent, with events such as the siege of Belgaum in 1473 by Muhammad Shah III.[165] Muslim and Hindu states in the south were advanced in artillery compared to the Delhi rulers of this period because of their contact with the outside world, especially Turkey, through the sea route. The south Indian kingdoms imported their gunners (topci) and artillery from Turkey and the Arab countries, with whom they had developed good relations.[166]

Korea

Korea had already come into possession of cannons by 1373, when a Korean mission was sent to China requesting gunpowder supplies for the artillery on their ships.[167] However Korea did not natively produce gunpowder until the years 1374–76.[168] In the 14th century a Korean scholar named Choe Museon discovered a way to produce it after visiting China and bribing a merchant by the name of Li Yuan for the gunpowder formula.[169] In 1377 he figured out how to extract potassium nitrate from the soil and subsequently invented the juhwa, Korea's first rocket,[170] and further developments led to the birth of singijeons, Korean arrow rockets. Korea also began producing cannons in 1377.[167] The multiple rocket launcher known as hwacha ("fire cart" 火車) was developed from the juhwa and singijeon in Korea by 1409 during the Joseon Dynasty. Its inventors include Yi Do (이도, not to be mistaken for Sejong the Great) and Choi Hae-san (최해산, son of Choe Museon).[171][172] However the first hwachas did not fire rockets, but used mounted bronze guns that shot iron-fletched darts.[173] Rocket launching hwachas were developed in 1451 under the decree of King Munjong and his younger brother Pe. ImYung (Yi Gu, 임영대군 이구). This "Munjong Hwacha" is the well-known type today, and could fire 100 rocket arrows or 200 small Chongtong bullets at one time with changeable modules. At the time, 50 units were deployed in Hanseong (present-day Seoul), and another 80 on the northern border. By the end of 1451, hundreds of hwachas were deployed throughout Korea.[171][174]

Naval gunpowder weapons also appeared and were rapidly adopted by Korean ships for conflicts against Japanese pirates in 1380 and 1383. By 1410, 160 Korean ships were reported to have equipped artillery of some sort. Mortars firing thunder-crash bombs are known to have been used, and four types of cannons are mentioned: chonja (heaven), chija (earth), hyonja (black), and hwangja (yellow), but their specifications are unknown. These cannons typically shot wooden arrows tipped with iron, the longest of which were nine feet long, but stone and iron balls were sometimes used as well.[175]

Japan

Firearms seem to have been known in Japan around 1270 as proto-cannons invented in China, which the Japanese called teppō (鉄砲 lit. "iron cannon").[176] Gunpowder weaponry exchange between China and Japan was slow and only a small number of hand guns ever reached Japan. However Japanese samurai used Fire lances in 15th-century.[177] The first recorded appearance of the Fire lances in Japan was in 1409.[178] The use of gunpowder bombs in the style of Chinese explosives is known to have occurred in Japan from at least the mid-15th century onward.[179] The first recorded appearance of the cannon in Japan was in 1510 when a Buddhist monk presented Hōjō Ujitsuna with a teppō iron cannon that he had acquired during his travels in China.[180] Firearms saw very little use in Japan until Portuguese matchlocks were introduced in 1543.[181] During the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), the forces of Toyotomi Hideyoshi effectively used matchlock firearms against the Korean forces of Joseon,[182] although they would ultimately be defeated and forced to withdraw from the Korean peninsula.

Africa

In Africa, the Adal Empire and the Abyssinian Empire both deployed gunpowder weapons during the Adal-Abyssinian War. Imported from Arabia, and the wider Islamic world, the Adalites, led by Ahmed ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi, were the first African power to introduce cannon warfare to the African continent.[183] Later on as the Portuguese Empire entered the war it would supply and train the Abyssinians with cannon and muskets, while the Ottoman Empire sent soldiers and cannon to back Adal. The conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearms such as the matchlock musket, cannon, and the arquebus over traditional weapons.[184]

Ernest Gellner in his book 'Nations and Nationalism' argues that the centralizing potential of the gun and the book, enabled both the Somali people and the Amhara people to dominate the political history of a vast area in Africa, despite neither of them being numerically predominant.[185]

"In the Horn of Africa both the Amharas and the Somalis possessed both gun and Book (not the same Book, but rival and different editions), and neither bothered greatly with the wheel. Each of these ethnic groups was aided in its use of these two pieces of cultural equipment by its link to other members of the wider religious civilization which habitually used them, and were willing to replenish their stock." – Ernest Gellner

Transition to early modern warfare

Early Ming firearms

Gun development and proliferation in China continued under the Ming dynasty. The success of its founder Zhu Yuanzhang, who declared his reign to be the era of Hongwu, or "Great Martiality," has often been attributed to his effective use of guns.

Most early Ming guns weighed two to three kilograms while guns considered "large" at the time weighed around only seventy-five kilograms. Ming sources suggest guns such as these shot stones and iron balls, but were primarily used against men rather than for causing structural damage to ships or walls. Accuracy was low and they were limited to a range of only 50 paces or so.[186]

Despite the relatively small size of early Ming guns, some elements of gunpowder weapon design followed world trends.[187] The growing length to muzzle bore ratio matched the rate at which European guns were developing up until the 1450s. The practice of corning gunpowder had been developed by 1370 for the purpose of increasing explosive power in land mines,[187] and was arguably used in guns as well according to one record of a fire-tube shooting a projectile 457 meters, which was probably only possible at the time with the usage of corned powder.[188] Around the same year Ming guns transitioned from using stone shots to iron ammunition, which has greater density and increased firearm power.[189] Aside from firearms, the Ming pioneered in the usage of rocket launchers known as "wasp nests", which it manufactured for the army in 1380 and was used by the general Li Jinglong in 1400 against Zhu Di, the future Yongle Emperor.[190]

The peak of Chinese cannon development prior to the incorporation of European weaponry in the 16th century is exemplified by the muzzle loading wrought iron "great general cannon" (大將軍炮) which weighed up to 360 kilograms and could fire a 4.8 kilogram lead ball. Its heavier variant, the "great divine cannon" (大神銃), could weigh up to 600 kilograms and was capable of firing several iron balls and upward of a hundred iron shots at once. The great general and divine cannons were the last indigenous Chinese cannon designs prior to the incorporation of European models in the 16th century.[191]

The lack of larger siege weapons in China unlike the rest of the world where cannons grew larger and more potent has been attributed to the immense thickness of traditional Chinese walls,[192] which Tonio Andrade suggests provided no incentive for creating larger cannons, since even industrial artillery had trouble overcoming them.[193] Asianist Kenneth Chase also argues that larger guns were not particularly useful against China's traditional enemies: horse nomads.[194]

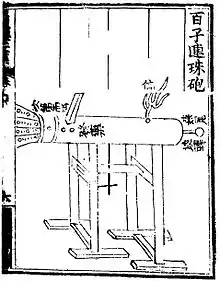

An organ gun known as the 'mother of a hundred bullets gun' (zi mu bai dan chong) from the Huolongjing.

An organ gun known as the 'mother of a hundred bullets gun' (zi mu bai dan chong) from the Huolongjing. An illustration of a bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon" from the Huolongjing.

An illustration of a bronze "thousand ball thunder cannon" from the Huolongjing. A seven barreled organ gun with two auxiliary guns by its side on a two-wheeled carriage. From the Huolongjing.

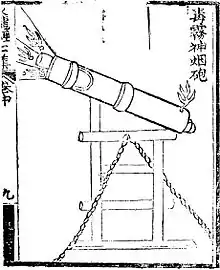

A seven barreled organ gun with two auxiliary guns by its side on a two-wheeled carriage. From the Huolongjing. A 'barbarian attacking cannon' as depicted in the Huolongjing. Chains are attached to the cannon to adjust recoil.

A 'barbarian attacking cannon' as depicted in the Huolongjing. Chains are attached to the cannon to adjust recoil. An "awe-inspiring long range cannon" (威遠砲), from the Huolongjing

An "awe-inspiring long range cannon" (威遠砲), from the Huolongjing A depiction of the "crouching tiger cannon" from the Huolongjing

A depiction of the "crouching tiger cannon" from the Huolongjing Drawing of a Great General Cannon, from 'Wu Bei Yao Lue (《武備要略》').

Drawing of a Great General Cannon, from 'Wu Bei Yao Lue (《武備要略》').

Big guns

The development of large artillery pieces began by Burgundy. Originally a minor power, the duchy grew to become one of the most powerful states in 14th-century Europe, and a great innovator in siege warfare. The Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold (1363–1404), based his power on the effective use of big guns and promoted research and development in all aspects of gunpowder weaponry technology. Philip established manufacturers and employed more cannon casters than any European power before him.

Whereas most European guns before 1370 weighed about 20 to 40 lbs (9–14 kg), the French siege of Château de Saint-Sauveur-le-Vicomte in 1375 during the Hundred Years War saw the use of guns weighing over a ton (900 kg), firing stone balls weighing over 100 lbs (45 kg).[195] Philip used large guns to help the French capture the fortress of Odruik in 1377. These guns fired projectiles far larger than any that had been used before, with seven guns that could shoot projectiles as heavy as 90 kilograms. The cannons smashed the city walls, inaugurating a new era of artillery warfare and Burgundy's territories rapidly expanded.[196]

Europe entered an arms race to build ever larger artillery pieces. By the early 15th century both French and English armies were equipped with larger pieces known as bombards, weighing up to 5 tons (4,535 kg) and firing balls weighing up to 300 lbs (136 kg).[195] The artillery trains used by Henry V of England in the 1415 Siege of Harfleur and 1419 Siege of Rouen proved effective in breaching French fortifications, while artillery contributed to the victories of French forces under Joan of Arc in the Loire Campaign (1429).[197]

These weapons were transformational for European warfare. A hundred years earlier the Frenchman Pierre Dubois wrote that a "castle can hardly be taken within a year, and even if it does fall, it means more expenses for the king's purse and for his subjects than the conquest is worth,"[198] but by the 15th century European walls fell with the utmost regularity.

The Ottoman Empire was also developing their own artillery pieces. Mehmed the Conqueror (1432–1481) was determined to procure large cannons for the purpose of conquering Constantinople. Hungarian Urban produced for him a six-meter (20-foot) long cannon, which required hundreds of pounds of gunpowder to fire; during the actual siege of Constantinople the gun proved to be somewhat underwhelming.[199] However, dozens of other large cannons bombarded Constantinople's walls in their weakest sections for 55 days,[199] and despite a fierce defense, the city's fortifications were overwhelmed.

Battle of Nicopolis 1398

Battle of Nicopolis 1398 Faule Metze (Metze, old term for a whore)("Lazy Mette"), a medieval supergun from 1411 from Braunschweig, Germany

Faule Metze (Metze, old term for a whore)("Lazy Mette"), a medieval supergun from 1411 from Braunschweig, Germany.jpg.webp) Thomas Montagu, 4th Earl of Salisbury is fatally injured at the siege of Orléans in 1428 (illustration from Vigiles de Charles VII).

Thomas Montagu, 4th Earl of Salisbury is fatally injured at the siege of Orléans in 1428 (illustration from Vigiles de Charles VII). Faule Magd ("Lazy Maid"), a medieval cannon from c. 1410–1430.

Faule Magd ("Lazy Maid"), a medieval cannon from c. 1410–1430. Mons Meg, a medieval Bombard (weapon) built in 1449.

Mons Meg, a medieval Bombard (weapon) built in 1449. The bronze Great Turkish Bombard, used by the Ottoman Empire in the siege of Constantinople in 1453.

The bronze Great Turkish Bombard, used by the Ottoman Empire in the siege of Constantinople in 1453.

Changes to fortifications

As a response to gunpowder artillery, European fortifications began displaying architectural principles such as lower and thicker walls in the mid-1400s.[200] Cannon towers were built with artillery rooms where cannons could discharge fire from slits in the walls. However this proved problematic as the slow rate of fire, reverberating concussions, and noxious fumes produced greatly hindered defenders. Gun towers also limited the size and number of cannon placements because the rooms could only be built so big. Notable surviving artillery towers include a seven layer defensive structure built in 1480 at Fougères in Brittany, and a four layer tower built in 1479 at Querfurth in Saxony.[201]

The star fort, also known as the bastion fort, tracé à l'italienne, or renaissance fortress, was a style of fortification that became popular in Europe during the 16th century. The bastion and star fort was developed in Italy, where the Florentine engineer Giuliano da Sangallo (1445–1516) compiled a comprehensive defensive plan using the geometric bastion and full tracé à l'italienne that became widespread in Europe.[202]