Human granulocytic anaplasmosis

Human granulocytic anaplasmosis (HGA) is a tick-borne, infectious disease caused by Anaplasma phagocytophilum, an obligate intracellular bacterium that is typically transmitted to humans by ticks of the Ixodes ricinus species complex, including Ixodes scapularis and Ixodes pacificus in North America. These ticks also transmit Lyme disease and other tick-borne diseases.[3]

| Human granulocytic anaplasmosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis (HGE)[1][2] |

| |

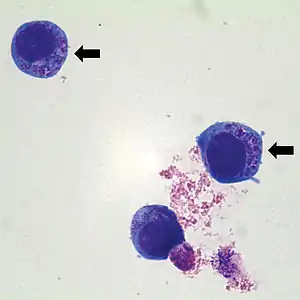

| Anaplasma phagocytophilum cultured in human | |

| Specialty | Infectious diseases |

The bacteria infect white blood cells called neutrophils, causing changes in gene expression that prolong the life of these otherwise short-lived cells.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms may include:

- fever

- severe headache

- muscle aches (myalgia)

- chills and shaking, similar to the symptoms of influenza

- nausea

- vomiting

- loss of appetite

- unintentional weight loss

- abdominal pain

- cough

- diarrhea,

- aching joints

- sensitivity to light

- weakness

- fatigue

- change in mental status (extreme confusion, memory loss, inability to comprehend environment- interaction, reading, etc.)

- temporary loss of basic motor skills

Symptoms may be minor, as evidenced by surveillance studies in high-risk areas. Gastrointestinal tract symptoms occur in less than half of patients and a skin rash is seen in less than 10% of patients.[5] It is also characterized by a low number of platelets, a low number of white blood cells, and elevated serum transaminase levels in the majority of infected patients.[5] Even though people of any age can get HGA, it is usually more severe in the aging or immune-compromised. Some severe complications may include respiratory failure, kidney failure, and secondary infections.

Cause

A. phagocytophilum is transmitted to humans by Ixodes ticks. These ticks are found in the US, Europe, and Asia. In the US, I. scapularis is the tick vector in the East and Midwest states, and I. pacificus in the Pacific Northwest.[6] In Europe, the I. ricinus is the main tick vector, and I. persulcatus is the currently known tick vector in Asia.[7]

The major mammalian reservoir for A. phagocytophilum in the eastern United States is the white-footed mouse, Peromyscus leucopus. Although white-tailed deer and other small mammals harbor A. phagocytophilum, evidence suggests that they are not a reservoir for the strains that cause HGA.[8][9] A tick that has a blood meal from an infected reservoir becomes infected themselves. If an infected tick then latches onto a human the disease is then transmitted to the human host and A. phagocytophilum symptoms can arise.[10]

Anaplasma phagocytophilum shares its tick vector with other human pathogens, and about 10% of patients with HGA show serologic evidence of coinfection with Lyme disease, babesiosis, or tick-borne meningoencephalitis.[11]

While it is rare, it is possible for HGA to be transmitted human-to-human via a blood transfusion, in which case it is called Transfusion-Transmitted Anaplasmosis (TTA).[12]

Major surface proteins

Many major surface proteins (MSPs) are found in Anaplasma and those which interact with Anaplasma can mainly be found in A. marginale and A. phagocytophilum.[13] There are many different phenotypic traits that are associated with MSPs, because each MSP can only infect certain animals in certain conditions.[13] A. phagocytophilum infects the most vast array of living things, including humans, and all around the world.[13] A. marginale evolved to be more specific in infecting animals, such as deer and cattle in the subtropics and tropics.[13] The main difference between these two MSPs is that the host cell for A. phagocytophilum is the granulocyte, while the host cell for A. marginale is erythrocytes.[13] It is likely that these MSPs coevolved, because they had previously interacted via tick-pathogen interaction.[13]

Anaplasma MSPs can not only cooperate with vertebrates, but also invertebrates, which make these phenotypes evolve faster than others, because they have a lot of selective forces acting on them.[13]

Diagnosis

Clinically, HGA is essentially indistinguishable from human monocytic ehrlichiosis, the infection caused by Ehrlichia chaffeensis, and other tick-borne illnesses such as Lyme disease may be suspected.[14] As Ehrlichia serologies can be negative in the acute period, PCR is very useful for diagnosis.[15]

Prevention

Currently, there is no vaccine against human granulocytic anaplasmosis, so antibiotics are the only form of treatment.[7] The best way to prevent HGA is to prevent getting tick bites.[16]

Treatment

Doxycycline is the treatment of choice. If anaplasmosis is suspected, treatment should not be delayed while waiting for a definitive laboratory confirmation, as prompt doxycycline therapy has been shown to improve outcomes.[14] Presentation during early pregnancy can complicate treatment. Doxycycline compromises dental enamel during development.[17] Although rifampin is indicated for post-delivery pediatric and some doxycycline-allergic patients, it is teratogenic. Rifampin is contraindicated during conception and pregnancy.[18]

If the disease is not treated quickly, sometimes before the diagnosis, the person has a high chance of mortality.[7] Most people make a complete recovery, though some people are intensively cared for after treatment.[7] A reason for a person needing intensive care is if the person goes too long without seeing a doctor or being diagnosed.[7] The majority of people, though, make a complete recovery with no residual damage.[7]

Epidemiology

From the first reported case in 1994 until 2010, HGA's rates of incidence have exponentially increased.[19] This is likely because HGA is found where there are ticks that carry and transmit Lyme disease, also known as Borrelia burgdorferi, and babesiosis, which is found in the northeastern and midwestern United States, which has seemingly increased in the past couple of decades.[19] Before 2000, there were less than 300 cases reported per year. In 2000, there were only 350 reported cases.[19] From 2009-2010, HGA experienced a 52% increase in the number of cases reported.[19]

History

The first outbreak of Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis (HGA) in the United States began with a patient in early 1990 in Wisconsin. He was kept in the hospital in Minnesota for testing, but died without a diagnosis.[7] Over the next couple of years, many people within the same area of Wisconsin and Minnesota had come down with the same symptoms.[7] It was discovered in 1994 that it was Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis (HGE), later to be known as HGA.[10]

Terminology

Although the infectious agent is known to be from the Anaplasma genus, the term "human granulocytic ehrlichiosis" (HGE) is often used, reflecting the prior classification of the organism. E. phagocytophilum and E. equi were reclassified as Anaplasma phagocytophilum.

See also

References

- Malik A, Jameel M, Ali S, Mir S (2005). "Human granulocytic anaplasmosis affecting the myocardium". J Gen Intern Med. 20 (10): C8–10. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00218.x. PMC 1490240. PMID 16191146.

- "Human Anaplasmosis Basics - Minnesota Dept. of Health". Archived from the original on 2018-03-14. Retrieved 2009-04-13.

- Holden, K.; Boothby, J. T.; Anand, S.; Massung, R. F. (2003). "Browse BioOne Complete". Journal of Medical Entomology. 40 (4): 534–9. doi:10.1603/0022-2585-40.4.534. ISSN 0022-2585. PMID 14680123.

- Lee HC, Kioi M, Han J, Puri RK, Goodman JL (September 2008). "Anaplasma phagocytophilum-induced gene expression in both human neutrophils and HL-60 cells". Genomics. 92 (3): 144–51. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2008.05.005. PMID 18603403.

- Murray, Patrick R.; Rosenthal, Ken S.; Pfaller, Michael A. Medical Microbiology, Fifth Edition. United States: Elsevier Mosby, 2005

- Dumler JS, Madigan JE, Pusterla N, Bakken JS (July 2007). "Ehrlichioses in humans: epidemiology, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45 (Suppl 1): S45–51. doi:10.1086/518146. PMID 17582569.

- Bakken, Johan S.; Dumler, J. Stephen (2006-10-01). "Clinical Diagnosis and Treatment of Human Granulocytotropic Anaplasmosis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1078 (1): 236–247. Bibcode:2006NYASA1078..236B. doi:10.1196/annals.1374.042. ISSN 1749-6632. PMID 17114714. S2CID 33910710.

- "Diagnosis and Management of Tickborne Rickettsial Diseases: Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Ehrlichioses, and Anaplasmosis --- United States A Practical Guide for Physicians and Other Health-Care and Public Health Professionals". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-10-21.

- Massung RF, Courtney JW, Hiratzka SL, Pitzer VE, Smith G, Dryden RL (October 2005). "Anaplasma phagocytophilum in white-tailed deer". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (10): 1604–6. doi:10.3201/eid1110.041329. PMC 3366735. PMID 16318705.

- Dumler, J. Stephen; Choi, Kyoung-Seong; Garcia-Garcia, Jose Carlos; Barat, Nicole S.; Scorpio, Diana G.; Garyu, Justin W.; Grab, Dennis J.; Bakken, Johan S. (2005). "Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1828–1834. doi:10.3201/eid1112.050898. PMC 3367650. PMID 16485466.

- Dumler JS, Choi KS, Garcia-Garcia JC, et al. (December 2005). "Human granulocytic anaplasmosis and Anaplasma phagocytophilum". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 11 (12): 1828–34. doi:10.3201/eid1112.050898. PMC 3367650. PMID 16485466.

- Goel, Ruchika; Westblade, Lars F.; Kessler, Debra A.; Sfeir, Maroun; Slavinski, Sally; Backenson, Bryon; et al. (August 2018). "Death from transfusion-transmitted anaplasmosis". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 24 (8): 1548–1550. doi:10.3201/eid2408.172048. PMC 6056119. PMID 30016241.

- de la Fuente, José; Kocan, Katherine M.; Blouin, Edmour F.; Zivkovic, Zorica; Naranjo, Victoria; Almazán, Consuelo; Esteves, Eliane; Jongejan, Frans; Daffre, Sirlei (2010-02-10). "Functional genomics and evolution of tick–Anaplasma interactions and vaccine development". Veterinary Parasitology. Ticks and Tick-borne Pathogens. 167 (2–4): 175–186. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2009.09.019. hdl:10261/144221. PMID 19819630.

- Hamburg BJ, Storch GA, Micek ST, Kollef MH (March 2008). "The importance of early treatment with doxycycline in human ehrlichiosis". Medicine. 87 (2): 53–60. doi:10.1097/MD.0b013e318168da1d. PMID 18344803. S2CID 2632346.

- Prince LK, Shah AA, Martinez LJ, Moran KA (August 2007). "Ehrlichiosis: making the diagnosis in the acute setting". Southern Medical Journal. 100 (8): 825–8. doi:10.1097/smj.0b013e31804aa1ad. PMID 17713310. S2CID 31487400.

- Wormser, Gary P.; Dattwyler, Raymond J.; Shapiro, Eugene D.; Halperin, John J.; Steere, Allen C.; Klempner, Mark S.; Krause, Peter J.; Bakken, Johan S.; Strle, Franc (2006-11-01). "The Clinical Assessment, Treatment, and Prevention of Lyme Disease, Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, and Babesiosis: Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 43 (9): 1089–1134. doi:10.1086/508667. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 17029130.

- Muffly T, McCormick TC, Cook C, Wall J (2008). "Human granulocytic ehrlichiosis complicating early pregnancy". Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2008: 1–3. doi:10.1155/2008/359172. PMC 2396214. PMID 18509484.

- Krause PJ, Corrow CL, Bakken JS (September 2003). "Successful treatment of human granulocytic ehrlichiosis in children using rifampin". Pediatrics. 112 (3 Pt 1): e252–3. doi:10.1542/peds.112.3.e252. PMID 12949322.

- "Statistics | Anaplasmosis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Retrieved 2015-11-08.

External links

- CDC Emerging Infectious Diseases for more information about HGE