Ghana

Ghana (/ˈɡɑːnə/ ⓘ GAH-nə; Twi: Gaana, Ewe: Gana, Dagbani: Gana), officially the Republic of Ghana, is a country in West Africa.[9] It abuts the Gulf of Guinea and the Atlantic Ocean to the south, sharing borders with Ivory Coast in the west, Burkina Faso in the north, and Togo in the east.[10] Ghana covers an area of 239,567 km2 (92,497 sq mi),[11] spanning diverse biomes that range from coastal savannas to tropical rainforests. With over 32 million inhabitants, Ghana is the second-most populous country in West Africa.[12] The capital and largest city is Accra; other cities are Kumasi, Tamale, and Sekondi-Takoradi.

Republic of Ghana | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Freedom and Justice" | |

| Anthem: "God Bless Our Homeland Ghana" | |

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Capital and largest city | Accra 05°33′18″N 00°11′33″W |

| Official languages | English[1][2] |

| Ethnic groups (2021 census[3]) |

|

| Religion (2021 census[3]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Ghanaian |

| Government | Unitary presidential republic |

| Nana Akufo-Addo | |

| Mahamudu Bawumia | |

| Alban Bagbin | |

| Gertrude Tokornoo | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Independence from the United Kingdom | |

| 6 March 1957 | |

• Republic | 1 July 1960 |

| Area | |

• Total | 239,567[4] km2 (92,497 sq mi) (80th) |

• Water (%) | 4.61 (11,000 km2; 4,247 mi2) |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 34,237,620 [5] (48th) |

• Density | 101.5/km2 (262.9/sq mi) (66th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2016) | medium |

| HDI (2021) | medium · 133rd |

| Currency | Cedi (GHS) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +233 |

| ISO 3166 code | GH |

| Internet TLD | .gh |

The earliest kingdoms to emerge in Ghana were the Kingdom of Dagbon in the north and the Bono state, with the Bono state existing in the area during the 11th century.[13][14] The Ashanti Empire and other Akan kingdoms in the south emerged over the centuries.[15] Beginning in the 15th century, the Portuguese Empire, followed by other European powers, contested the area for trading rights, until the British ultimately established control of the coast by the 19th century. Following over a century of colonial resistance, the current borders of the country took shape, encompassing 4 separate British colonial territories: Gold Coast, Ashanti, the Northern Territories, and British Togoland. These were unified as an independent dominion within the Commonwealth of Nations. On 6 March 1957, Ghana became the first country in Sub-Saharan Africa to achieve sovereignty.[16][17][18] Ghana subsequently became influential in decolonisation efforts and the Pan-African movement.[19]

Ghana is a multi-ethnic country with linguistic and religious groups;[20] while the Akan are the largest ethnic group, they constitute a plurality. Most Ghanaians are Christians (71.3%); almost a fifth are Muslims; a tenth practise traditional faiths or report no religion.[3] Ghana is a unitary constitutional democracy led by a president who is head of state and head of government.[21] For political stability in Africa, Ghana ranked 7th in the 2012 Ibrahim Index of African Governance and 5th in the 2012 Fragile States Index. It has maintained since 1993 one of the freest and most stable governments on the continent, and it performs relatively well in healthcare, economic growth, and human development,[19] so that it has a significant influence in West Africa and Africa as a whole.[22] Ghana is highly integrated in international affairs, being a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement, African Union and a member of the Economic Community of West African States, Group of 24 and Commonwealth of Nations.[23]

History

Medieval kingdoms

_MET_DP108293.jpg.webp)

The earliest recorded kingdoms to emerge in modern Ghana were the Mole-Dagbon states.[24] Before the unification of Dagbon, societies were decentralised, and headed by the Tindaamba (singular: tindana).[25] These decentralised states were unified by King Gbewaa, who lived a long life, and formed a stable, peaceful society.[26] Dagbon extended beyond the boundaries of present day Ghana.[27] [28][29] Kingdoms that emerged from Dagbon include the Mossi Kingdoms of Burkina Faso,[30] and Bouna Kingdom of Ivory Coast.[31] The kingdom enjoyed great prosperity establishing Ghana's earliest educational systems,[32] and using a writing script[33][34] prior to European invasion. Female chiefs who rule over male subjects are present in the kingdom,[35] and inheritance is both patrilineal ad matrilineal.[36] The Yaa Naa is the King of Dagbon and the Gundo Naa is the Queen.[37][38] The kingdom remained uncolonised. In 1896, Germany invaded Eastern Dagbon (Naya) and burnt down its capital, Yendi,[39][40] during the Battle of Adibo.[41][42]

The Akan-speaking peoples began to move into what later became Ghana toward the 15th century.[24][43] By the 16th century, the Akans were established in the Akan state called Bonoman, for which the Brong-Ahafo region was named.[24][44] From the 17th century, Akans emerged from what is believed to have been the Bonoman area, to create Akan states, mainly based on gold trading.[45] These states included Bonoman (Brong-Ahafo region), Ashanti (Ashanti Region), Denkyira (Western North region), Mankessim Kingdom (Central region), and Akwamu (Eastern region).[24] By the 19th century, the territory of the southern part of Ghana was included in the Kingdom of Ashanti.[24] The government of the Ashanti Empire operated first as a loose network and eventually as a centralised kingdom with a specialised bureaucracy centred in the capital city of Kumasi.[24] Prior to Akan contact with Europeans, the Akan people created an economy based on principally gold and gold bar commodities, which were traded with other states in Africa.[24][46] The Ga-Dangme and Ewe migrated westward from south-western Nigeria. The Ewe migrated from Oyo area with their Gbe-speaking kinsmen (Adja, Fon, Phera Gun)and in transition, settled in Ketou in Benin Republic, Tado in Togo and with Nortsie ( a walled town on present-day Togo)as their final dispersal point. Their dispersal from Nortsie was necessitated by the high-handed rule of King Agorkorli (Agor Akorlie). The Ga- Dangme occupy the Greater Accra Region and parts of the Eastern Region, while the Ewe are found in the Volta Region as well as the neighbouring Togo, Benin Republic and Nigeria ( around Badagry area).

European contact and colonialism

Akan trade with European states began after contact with the Portuguese in the 15th century.[47] European contact was by the Portuguese people, who came to the Gold Coast region in the 15th century to trade. The Portuguese then established the Portuguese Gold Coast (Costa do Ouro), focused on the availability of gold.[48] The Portuguese built a trading lodge at a coastal settlement called Anomansah (the perpetual drink) which they renamed São Jorge da Mina.[48] In 1481, King John II of Portugal commissioned Diogo de Azambuja to build the Elmina Castle, which was completed in 3 years.[48] By 1598, the Dutch had joined the Portuguese in the gold trade, establishing the Dutch Gold Coast (Nederlandse Bezittingen ter Kuste van Guinea - 'Dutch properties at the Guinea coast') and building forts at Fort Komenda and Kormantsi.[49] In 1617, the Dutch captured the Elmina Castle from the Portuguese and Axim in 1642 (Fort St Anthony).[49]

European traders had joined in gold trading by the 17th century, including the Swedes, establishing the Swedish Gold Coast (Svenska Guldkusten), and Denmark–Norway, establishing the Danish Gold Coast (Danske Guldkyst or Dansk Guinea).[50] European traders participated in the Atlantic slave trade in this area.[51] More than 30 forts and castles were built by the merchants. The Germans established the Brandenburger Gold Coast or Groß Friedrichsburg).[52] In 1874, Great Britain established control over some parts of the country, assigning these areas the status of the British Gold Coast.[53] Military engagements occurred between British colonial powers and Akan nation-states. The Kingdom of Ashanti defeated the British some times in the 100-year-long Anglo-Ashanti wars and eventually lost with the War of the Golden Stool in 1900.[54][55][56]

Transition to independence

In 1947, the newly formed United Gold Coast Convention led by "The Big Six" called for "self-government within the shortest possible time" following the 1946 Gold Coast legislative election.[50][57] Kwame Nkrumah, a Ghanaian nationalist who led Ghana from 1957 to 1966 as the country's first prime minister and president, formed the Convention People's Party in 1949 with the motto "self-government now".[50] The party initiated a "positive action" campaign involving non-violent protests, strikes and non-cooperation with the British authorities. Nkrumah was arrested and sentenced to one year imprisonment during this time. In the Gold Coast's 1951 general election, he was elected to Parliament and was released from prison.[50] He became prime minister in 1952 and began a policy of Africanization.

On 6 March 1957 at midnight, the Gold Coast, Ashanti, the Northern Territories, and British Togoland were unified as one single independent dominion within the British Commonwealth under the name Ghana. This was done under the Ghana Independence Act 1957. The current flag of Ghana, consisting of the colours red, gold, green, and a black star, dates back to this unification.[58] On 1 July 1960, following the Ghanaian constitutional referendum and Ghanaian presidential election, Nkrumah declared Ghana a republic and assumed the presidency.[16][17][18][50] 6 March is the nation's Independence Day, and 1 July is celebrated as Republic Day.[59][60]

Nkrumah led an authoritarian regime in Ghana, as he repressed political opposition and conducted elections that were not free and fair.[61][62][63][64][65] In 1964, a constitutional amendment made Ghana a one-party state, with Nkrumah as president for life of both the nation and its party.[66] Nkrumah was the first African head of state to promote the concept of Pan-Africanism, which he had been introduced to during his studies at Lincoln University, Pennsylvania in the United States, at the time when Marcus Garvey was known for his "Back to Africa Movement".[50] He merged the teachings of Garvey, Martin Luther King Jr. and the naturalised Ghanaian scholar W. E. B. Du Bois into the formation of 1960s Ghana.[50] Osagyefo Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, as he became known, played an instrumental part in the founding of the Non-Aligned Movement, and in establishing the Kwame Nkrumah Ideological Institute to teach his ideologies of communism and socialism.[67] His life achievements were recognised by Ghanaians during his centenary birthday celebration, and the day was instituted as a public holiday in Ghana (Founders' Day).[68]

Operation Cold Chop and aftermath

The government of Nkrumah was subsequently overthrown in a coup by the Ghana Armed Forces, codenamed "Operation Cold Chop". This occurred while Nkrumah was abroad with Zhou Enlai in the People's Republic of China, on a fruitless mission to Hanoi, Vietnam, to help end the Vietnam War. The coup took place on 24 February 1966, led by Colonel Emmanuel Kwasi Kotoka and Brigadier Akwasi Afrifa. The National Liberation Council was formed, chaired by Lieutenant General Joseph A. Ankrah.[69]

A series of alternating military and civilian governments, often affected by economic instabilities,[70] ruled Ghana from 1966, ending with the ascent to power of Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings of the Provisional National Defence Council in 1981.[71] These changes resulted in the suspension of the constitution in 1981 and the banning of political parties.[72] The economy soon declined, so Rawlings negotiated a structural adjustment plan, changing many old economic policies, and growth recovered during the mid-1980s.[72] A new constitution restoring multi-party system politics was promulgated in the presidential election of 1992, in which Rawlings was elected, and again in the general election of 1996.[73]

In a tribal war in Northern Ghana in 1994, between the Konkomba and other ethnic groups, including the Nanumba, Dagomba and Gonja, between 1,000 and 2,000 people were killed and 150,000 people were displaced.[74]

After the 2000 general election, John Kufuor of the New Patriotic Party became president of Ghana on 7 January 2001 and was re-elected in 2004, thus also serving two terms (the term limit) as president of Ghana and marking the first time under the fourth republic that power was transferred from one legitimately elected head of state and head of government to another.[73]

Nana Akufo-Addo, the ruling party candidate, was defeated in a very close 2008 general election by John Atta Mills of the National Democratic Congress.[75][76] Mills died of natural causes and was succeeded by Vice President John Mahama on 24 July 2012.[77] Following the 2012 general election, Mahama became president in his own right,[78] and Ghana was described as a "stable democracy".[79][80] As a result of the 2016 general election,[81] Nana Akufo-Addo became president on 7 January 2017.[82] He was re-elected after a tightly contested election in 2020.[83]

To combat deforestation, on 11 June 2021 Ghana inaugurated Green Ghana Day, with the aim of planting 5 million trees in a concentrated effort to preserve the country's rainforest cover.[84]

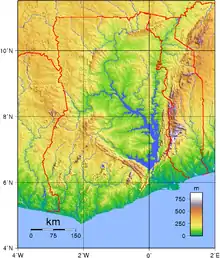

Geography

Ghana is located on the Gulf of Guinea, a few degrees north of the Equator.[85] It spans an area of 239,535 km2 (92,485 sq mi)[86] and has an Atlantic coastline that stretches 560 kilometres (350 miles) on the Gulf of Guinea in the Atlantic Ocean to its south.[85] Dodi Island and Bobowasi Island are near the south coast.[87] It lies between latitudes 4°45'N and 11°N, and longitudes 1°15'E and 3°15'W. The prime meridian passes through Ghana, specifically through Tema.[85] Ghana is geographically closer to the intersection of the Prime Meridian and the Equator than any other country, since this point, (0°, 0°), is located in the Atlantic Ocean approximately 614 km (382 mi) off the south-east coast of Ghana.

Grasslands mixed with south coastal shrublands and forests dominate Ghana, with forest extending northward from the coast 320 kilometres (200 miles) and eastward for a maximum of about 270 kilometres (170 miles) with locations for mining of industrial minerals and timber.[85] Ghana is home to 5 terrestrial ecoregions: Eastern Guinean forests, Guinean forest–savanna mosaic, West Sudanian savanna, Central African mangroves, and Guinean mangroves.[88] It had a 2018 Forest Landscape Integrity Index mean score of 4.53/10, ranking it 112th globally out of 172 countries.[89]

The White Volta River and its tributary Black Volta, flow south through Ghana to Lake Volta, the world's third-largest reservoir by volume and largest by surface area, formed by the hydroelectric Akosombo Dam,[90] completed in 1965. The Volta flows out of Lake Volta into the Gulf of Guinea.[91] The northernmost part of Ghana is Pulmakong and the southernmost part of Ghana is Cape Three Points.[85]

The climate of Ghana is tropical, and there is wet season and dry season.[93] Ghana sits at the intersection of 3 hydro-climatic zones.[94] Changes in rainfall, weather conditions and sea-level rise affect the salinity of coastal waters. This is expected to negatively affect both farming and fisheries.[95]

In 2015, the government produced a document titled "Ghana's Intended Nationally Determined Contribution."[96] Following that, Ghana signed the Paris Climate Agreement in 2016.

Politics

Ghana is a unitary presidential constitutional democracy with a parliamentary multi-party system that is dominated by two parties—the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and the New Patriotic Party (NPP). Ghana alternated between civilian and military governments until January 1993, when the military government gave way to the Fourth Republic of Ghana after presidential and parliamentary elections in late 1992. The 1992 constitution of Ghana divides powers among a commander-in-chief of the Ghana Armed Forces (President of Ghana), parliament (Parliament of Ghana), cabinet (Cabinet of Ghana), council of state (Ghanaian Council of State), and an independent judiciary (Judiciary of Ghana). The government is elected by universal suffrage after every four years.[97] Nana Akufo-Addo won the presidency in the general election in 2016, defeating incumbent John Mahama. He also won the 2020 election after the presidential election results were challenged at the Supreme Court by flagbearer of the NDC, John Mahama. Presidents are limited to two four-year terms in office. The president can serve a second term only upon re-election. The 2012 Fragile States Index indicated that Ghana is ranked the 67th-least fragile state in the world and the fifth-least fragile state in Africa. Ghana ranked 112th out of 177 countries on the index.[98] Ghana ranked as the 64th-least corrupt and politically corrupt country in the world out of all 174 countries ranked and ranked as the fifth-least corrupt and politically corrupt country in Africa out of 53 countries in the 2012 Transparency International Corruption Perception Index.[99][100] Ghana was ranked 7th in Africa out of 53 countries in the 2012 Ibrahim Index of African Governance. The Ibrahim Index is a comprehensive measure of African government, based on variables which reflect the success with which governments deliver essential political goods to its citizens.[101]

Foreign relations

Since independence, Ghana has been devoted to ideals of nonalignment and is a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement. Ghana favours international and regional political and economic co-operation, and is an active member of the United Nations and the African Union.[102]

Ghana has a strong relationship with the United States. Three recent U.S. presidents—Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama and a Vice President — Kamala Harris made diplomatic trips to Ghana.[103] Many Ghanaian diplomats and politicians hold positions in international organisations, including Ghanaian diplomat and former Secretary-General of the United Nations Kofi Annan, International Criminal Court Judge Akua Kuenyehia, as well as former President Jerry John Rawlings and former President John Agyekum Kufuor, who both served as diplomats of the United Nations.[97]

In September 2010, President John Atta Mills visited China on an official visit. Mills and China's former President Hu Jintao marked the 50th anniversary of diplomatic ties between the two nations, at the Great Hall of the People.[104] China reciprocated with an official visit in November 2011, by the vice-chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress of China, Zhou Tienong who visited Ghana and met with Ghana's President John Mahama.[105] Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad met with Mahama in 2013 to hold discussions on strengthening the Non-Aligned Movement and also co–chair a bilateral meeting between Ghana and Iran at the Ghanaian presidential palace Flagstaff House.[106][107][108][109][110]

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) were integrated into Ghana's development agenda and the budget. According to reports, the SDGs were implemented through a decentralized planning approach. This allows for stakeholders' participation, such as in UN agencies, traditional leaders, civil society organizations, academia, and others.[111] The 17 SDGs are a global call to action to end poverty among others, and the UN and its partners in the country are working towards achieving them.[112] According to the President Nana Akufo-Addo, Ghana was "the first sub-Saharan African country to achieve the goal of halving poverty, as contained in Goal 1 of the Millennium Development Goals"[113]

Military

In 1957, the Ghana Armed Forces (GAF) consisted of its headquarters, support services, three battalions of infantry and a reconnaissance squadron with armoured vehicles.[114] President Nkrumah aimed at rapidly expanding the GAF to support the United States of Africa ambitions. Thus, in 1961, 4th and 5th Battalions were established, and in 1964 6th Battalion was established, from a parachute airborne unit originally raised in 1963.[115] Today, Ghana is a regional power and regional hegemon.[22] In his book Shake Hands with the Devil, Canadian Forces commander Roméo Dallaire highly rated the GAF soldiers and military personnel.[114]

The military operations and military doctrine of the GAF are conceptualised in the constitution, Ghana's Law on Armed Force Military Strategy, and Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre agreements to which GAF is attestator.[116][117][118] GAF military operations are executed under the auspices and imperium of the Ministry of Defence.[116][119] Although Ghana is relatively peaceful and is often considered being one of the least violent countries in the region, Ghana has experienced political violence in the past and 2017 has thus far seen an upward trend in incidents motivated by political grievances.[120]

Law enforcement

The Ghana Police Service and the Criminal Investigation Department are the main law enforcement agencies, responsible for the detection of crime, maintenance of law and order and the maintenance of internal peace and security.[121] The Ghana Police Service has eleven specialised police units, including a Militarized police Rapid deployment force and Marine Police Unit.[122][123] The Ghana Police Service operates in 12 divisions: ten covering the regions of Ghana, one assigned specifically to the seaport and industrial hub of Tema, and the twelfth being the Railways, Ports and Harbours Division.[123] The Ghana Police Service's Marine Police Unit and Division handles issues that arise from the country's offshore oil and gas industry.[123]

The Ghana Prisons Service and the sub-division Borstal Institute for Juveniles administers incarceration.[124] Ghana retains and exercises the death penalty for treason, corruption, robbery, piracy, drug trafficking, rape, and homicide.[125][126] The new sustainable development goals adopted by the United Nations call for the international community to come together to promote the rule of law; support equal access to justice for all; reduce corruption; and develop effective, accountable, and transparent institutions at all levels.[127]

Ghana is used as a key narcotics industry transshipment point by traffickers, usually from South America as well as some from other African nations.[128] In 2013, the UN chief of the Office on Drugs and Crime stated that "West Africa is completely weak in terms of border control and the big drug cartels from Colombia and Latin America have chosen Africa as a way to reach Europe."[129] There is not a wide or popular knowledge about the narcotics industry and intercepted narcotics within Ghana, since it is an underground economy. The social context within which narcotic trafficking, storage, transportation, and repacking systems exist in Ghana and the state's location along the Gulf of Guinea makes Ghana an attractive country for the narcotics business.[128][130] The Narcotics Control Board has impounded container ships at the Sekondi Naval Base in the Takoradi Harbour. These ships were carrying thousands of kilograms of cocaine, with a street value running into billions of Ghana cedis. However, drug seizures saw a decline in 2011.[128][130] Drug cartels are using new methods in narcotics production and narcotics exportation, to avoid Ghanaian security agencies.[128][130] Underdeveloped institutions, porous open borders, and the existence of established smuggling organisations contribute to Ghana's position in the narcotics industry.[128][130] President Mills initiated ongoing efforts to reduce the role of airports in Ghana's drug trade.[128]

Human rights

Homosexual acts are prohibited by law in Ghana.[131] According to a 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center, 96% of Ghanaians believe that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[132] Sometimes elderly women in Ghana are accused of witchcraft, particularly in rural Ghana. Issues of witchcraft mainly remain as speculations based on superstitions within families. In some parts of northern Ghana, there exist what are called witch camps. These are said to house a total of around 1,000 people accused of witchcraft.[133] The Ghanaian government has announced that it intends to close the camps.[133]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

Ghana possesses industrial minerals, hydrocarbons and precious metals. It is an emerging designated digital economy with mixed economy hybridisation and an emerging market. It has an economic plan target known as the "Ghana Vision 2020". This plan envisions Ghana as the first African country to become a developed country between 2020 and 2029 and a newly industrialised country between 2030 and 2039.[134] This excludes fellow Group of 24 member and Sub-Saharan African country South Africa, which is a newly industrialised country.[135]

Ghana's economy has ties to the Chinese yuan renminbi along with Ghana's vast gold reserves. In 2013, the Bank of Ghana began circulating the renminbi throughout Ghanaian state-owned banks and to the Ghana public as hard currency along with the national Ghanaian cedi for second national trade currency.[136]

Between 2012 and 2013, 38% of rural dwellers were experiencing poverty whereas only 11% of urban dwellers were.[137] Urban areas hold greater opportunity for employment, particularly in informal trade, while nearly all (94 percent) of "rural poor households" participate in the agricultural sector.[138]

The Volta River Authority and the Ghana National Petroleum Corporation, both state-owned, are the two major electricity producers.[139] The Akosombo Dam, built on the Volta River in 1965, along with the Bui Dam, the Kpong Dam and several other hydroelectric dams, provide hydropower.[140][141] In addition, the government sought to build the second nuclear power plant in Africa.

The Ghana Stock Exchange is the 5th largest on continental Africa and 3rd largest in sub-saharan Africa with a market capitalisation of GH¢ 57.2 billion or CN¥180.4 billion in 2012 with the South Africa JSE Limited as first.[142] The Ghana Stock Exchange was the 2nd best performing stock exchange in sub-saharan Africa in 2013.[143]

Ghana produces high-quality cocoa.[144] It is the 2nd largest producer of cocoa globally.[145] Ghana is classified as a middle income country.[6][146] Services account for 50% of GDP, followed by manufacturing (24.1%), extractive industries (5%), and taxes (20.9%).[139] Ghana has an increasing primary manufacturing economy and export of digital technology goods along with assembling and exporting automobiles and ships, diverse resource rich exportation of industrial minerals, agricultural products primarily cocoa, petroleum and natural gas,[147] and industries such as information and communications technology primarily via Ghana's state digital technology corporation Rlg Communications which manufactures tablet computers with smartphones and various consumer electronics.[139][148] Urban electric cars have been manufactured in Ghana since 2014.[149][150]

It announced plans to issue government debt by way of social and green bonds in Autumn 2021 making it the first African country to do so.[151][152] The country, which is planning to borrow up to $5 billion in international markets this year, would use the proceeds from these sustainable bonds to refinance debt used for social and environmental projects and pay for educational or health. Only a few other nations have sold them so far, including Chile and Ecuador. The country will use the proceeds to forge ahead with a free secondary-school initiative started in 2017 among other programs, despite having recorded its lowest economic growth rate in 37 years in 2020.[153]

_and_National_Petroleum_Authority.png.webp)

It produces and exports hydrocarbons such as sweet crude oil and natural gas.[154][155] The 100%-state-owned filling station company, Ghana Oil Company, is the number 1 petroleum and gas filling station, and the 100%-state-owned state oil company Ghana National Petroleum Corporation oversees hydrocarbon exploration and production of petroleum and natural gas reserves. Ghana aims to further increase the output of oil to 2.2 million barrels (350,000 m3) per day and gas to 34,000,000 cubic metres (1.2×109 cu ft) per day.[156] The Jubilee Oil Field, which contains up to 3 billion barrels (480,000,000 m3) of sweet crude oil, was discovered in 2007.[157] Ghana is believed to have up to 5 billion barrels (790,000,000 m3) to 7 billion barrels (1.1×109 m3) of petroleum in reserves,[158] which is the fifth-largest in Africa and the 21st-to-25th-largest proven reserves in the world. It also has up to 1.7×1011 cubic metres (6×1012 cu ft) of natural gas in reserves.[159] The government has drawn up plans to nationalise petroleum and natural gas reserves to increase government revenue.[160]

As of 2019, Ghana was the 7th largest producer of gold in the world, producing ~140 tonnes that year.[161] This record saw Ghana surpass South Africa in output for the first time, making Ghana the largest gold producer in Africa.[162] In addition to gold, Ghana exports silver, timber, diamonds, bauxite, and manganese, and has other mineral deposits.[163] Ghana ranks 9th in the world in diamond export and reserve size.[164] The government has drawn up plans to nationalize mining industry to increase government revenue.[165][166]

"Shortages" of electricity in 2015 & 2016 led to dumsor ("persistent, irregular and unpredictable" electric power outages),[167] increasing the interest in renewables.[168] As of 2019, there is a surplus of electricity.[169]

The judicial system of Ghana deals with corruption, economic malpractice and lack of economic transparency.[170] According to Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index of 2018, out of 180 countries, Ghana was ranked 78th, with a score of 41 on a scale where a 0–9 score means highly corrupt, and a 90–100 score means very clean. This was based on perceived levels of public sector corruption.[171]

Science and technology

It launched a cellular mobile network (1992). It was connected to the internet and introduced ADSL broadband services.[172] It was ranked 112nd in the Global Innovation Index in 2021, down from 106th in 2019.[173][174][175][176]

The Ghana Space Science and Technology Centre (GSSTC) and Ghana Space Agency (GhsA) oversee space exploration and space programmes. GSSTC and GhsA worked to have a national security observational satellite launched into orbit in 2015.[177][178] Ghana's annual space exploration expenditure has been 1% of its GDP, to support research in science and technology. In 2012, Ghana was elected to chair the Commission on Science and Technology for Sustainable Development in the South (Comsats); Ghana has a joint effort in space exploration with the South African National Space Agency.[177]

Tourism

In 2011, 1,087,000 tourists visited Ghana.[179] Tourist arrivals include South Americans, Asians, Europeans, and North Americans.[180] The attractions and tourist destinations include waterfalls such as Kintampo waterfalls and the largest waterfall in west Africa, Wli waterfalls, the coastal palm-lined sandy beaches, caves, mountains, rivers, and reservoirs and lakes such as Lake Bosumtwi and the largest human-made lake in the world by surface area, Lake Volta, dozens of forts and castles, World Heritage Sites, nature reserves and national parks.[180] Some castles are Cape Coast Castle and the Elmina Castle.[181] Castles mark where blood was shed in the slave trade and preserve and promote the African heritage stolen and destroyed through the slave trade.[182] As a result of this, the World Heritage Convention of UNESCO named Ghana's castles and forts as World Heritage Monuments.[182]

The World Economic Forum statistics in 2010 showed that out of the world's favourite tourist destinations, Ghana was ranked 108th out of 139 countries.[183] The country had moved 2 places up from the 2009 rankings. In 2011, Forbes magazine published that Ghana was ranked the eleventh most friendly country in the world. The assertion was based on a survey in 2010 of a cross-section of travellers. Of all the African countries that were included in the survey, Ghana ranked highest.[183] Tourism is the fourth highest earner of foreign exchange for the country.[183] In 2017, Ghana ranked as the 43rd–most peaceful country in the world.[184]

Up and down the coastline, surfing spots have been identified and cultivated by locals and internationals. Surfers have made trips to the country to sample the waves. Surfers carried their boards amid traditional fishing vessels.[185]

According to Destination Pride[186]–a data-driven search platform used to visualize the world's LGBTQ+ laws, rights and social sentiment–Ghana's Pride score is 22 (out of 100).[187]

Demographics

As of 2019, Ghana has a population of 30,083,000.[188] Around 29% of the population is under the age of 15, while persons aged 15–64 make up 57.8 percent of the population.[189] The 2010 census reported that the largest ethnic groups are the Akan (47.3%), the Mole-Dagbani (16.6%), the Ewe (13.9%), the Ga-Dangme (7.4%), the Gurma (5.7%) and the Guan (3.7%).[190]

The median age of Ghanaian citizens is 30 years old and the average household size is 3.6 persons.

With recent legal immigration of skilled workers who possess Ghana Cards, there is a small population of Chinese, Malaysian, Indian, Middle Eastern and European nationals. In 2010, the Ghana Immigration Service reported many economic migrants and Illegal immigrants inhabiting Ghana: 14.6% (or 3.1 million) of Ghana's 2010 population (predominantly Nigerians, Burkinabe citizens, Togolese citizens, and Malian citizens). In 1969, under the "Ghana Aliens Compliance Order" enacted by Prime Minister Kofi Abrefa Busia,[191] the Border Guard Unit deported over 3,000,000 aliens and illegal immigrants in three months as they made up 20% of the population at the time.[191][192][193] In 2013, there was a mass deportation of illegal miners, more than 4,000 of them Chinese nationals.[194][195]

Languages

_LOC_88692692.jpg.webp)

English is the official language of Ghana.[196][197] Additionally, there are eleven languages that have the status of government-sponsored languages:

- Akan languages (Asante Twi, Akuapem Twi, Fante which have a high degree of mutual intelligibility, and Nzema, which is less intelligible with the above)

- Dangme

- Ewe

- Ga

- Guan

- Kasem

- Mole-Dagbani languages (Dagaare and Dagbanli)[198][199]

Of these, Asante Twi is the most widely spoken.[200]

Because Ghana is surrounded by French-speaking countries, French is widely taught in schools and used for commercial and international economic exchanges. Since 2006, Ghana has been an associate member of the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie,[201] the global organisation that unites French-speaking countries (84 nations on six continents). In 2005, more than 350,000 Ghanaian children studied French in schools. Since then, its status has been progressively updated to a mandatory language in every junior high school,[202] and it is in the process of becoming an official language.[203][204]

Ghanaian Pidgin English, also known as Kru English (or in Akan, kroo brofo), is a variety of West African Pidgin English spoken in Accra and in the southern towns.[205] It can be divided into two varieties, referred to as "uneducated" or "non-institutionalized" pidgin and "educated" or "institutionalized" pidgin, the former associated with uneducated or illiterate people and the latter acquired and used in institutions such as universities.[206]

Religion

Christianity is the largest religion in Ghana, with 71.3% of the population being members of various Christian denominations as of the 2021 census.[207] Islam is practised by 19.9% of the total population. According to a 2012 report by Pew Research, 51% of Muslims are followers of Sunni Islam, while approximately 16% belong to the Ahmadiyya movement and around 8% identify with Shia Islam, while the remainder are non-denominational Muslims.[208][209] There is "no significant link between ethnicity and religion in Ghana".[210]

Universal health care and life expectancy

Ghana has a universal health care system strictly designated for Ghanaian nationals, National Health Insurance Scheme (NHIS), is designated for Ghanaian nationals.[211] Health care is variable throughout Ghana and in 2012, over 12 million Ghanaian nationals were covered by the NHIS.[212] Urban centres are well served and contain most of the hospitals, clinics, and pharmacies. There are over 200 hospitals, and Ghana is a destination for medical tourism.[213] In 2010, there were 0.1 physicians per 1,000 people and as of 2011, 0.9 hospital beds per 1,000 people.[189] 5.2% of Ghana's GDP was spent on health in 2010.[214] In 2020, the WHO announced Ghana became the second country in the WHO African Region to attain regulatory system "maturity level 3", the second-highest in the four-tiered WHO classification of National medicines regulatory systems.[215]

Life expectancy at birth in 2020 was 71 for a female and 65 for a male.[216] In 2013, infant mortality was to 39 per 1,000 live births.[217] Sources vary on life expectancy at birth; the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 62 years for men and 64 years for women born in 2016.[218] The fertility rate declined from 3.99 (2000) to 3.28 (2010) with 2.78 in urban region and 3.94 in rural region.[190] The United Nations reports a fertility decline from 6.95 (1970) to 4.82 (2000) to 3.93 live births per woman in 2017.[219]

As of 2012, the HIV/AIDS prevalence was estimated at 1.40% among adults aged 15–49.[220]

Education

The education system is divided into 3 parts: basic education, secondary cycle, and tertiary education. "Basic education" lasts 11 years (ages 4‒15).[221] It is divided into kindergarten (2 years), primary school (2 modules of 3 years) and junior high (3 years). Junior high school ends with the Basic Education Certificate Examination.[221][222] Once certified, the pupil can proceed to the secondary cycle.[223] Hence, the pupil has the choice between general education (offered by the senior high school) and vocational education (offered by the technical senior high school or the technical and vocational institutes). Senior high school lasts 3 years and leads to the West African Senior School Certificate Examination, which is a prerequisite for enrollment in a university bachelor's degree programme.[224]: 7 Polytechnics are open to vocational students.[225]

A bachelor's degree requires 4 years of study. It can be followed by a 1- or 2-year master's degree programme, which can be followed by a PhD programme of at least 3 years.[224]: 9 A polytechnic programme lasts 2 or 3 years.[225] Ghana possesses colleges of education.[226] Some of the universities are the University of Ghana, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, and University of Cape Coast.[227]

There are over 95% of children in school.[228][229] The female and male ages 15–24 years literacy rate was 81% in 2010, with males at 82%,[230] and females at 80%.[231] A education system annually attracts foreign students particularly in the university sector.[232][233]

Ghana has a free education 6-year primary school education system beginning at age 6.[234] The government largely funds basic education comprising public primary schools and public junior high schools. Senior high schools were subsidised by the government until September 2017/2018 academic year that senior high education became free.[235] At the higher education level, the government funds more than 80% of resources provided to public universities, polytechnics and teacher training colleges. As part of the Free Compulsory Universal Basic Education, Fcube, the government supplies all basic education schools with all their textbooks and other educational supplies, like exercise books. Senior high schools are provided with all their textbook requirements by the government. Private schools acquire their educational material from private suppliers.[236]

Culture

.jpg.webp)

Food and drink

Ghanaian cuisine includes an assortment of soups and stews with varied seafoods; most Ghanaian soups are prepared with vegetables, meat, poultry or fish.[237] Fish is important in the diet with tilapia, roasted and fried whitebait, smoked fish and crayfish, all being common components of Ghanaian dishes.[237] Banku (akple) is a common starchy food made from ground corn (maize),[237] and cornmeal based staples kɔmi (kenkey) and banku (akple) are usually accompanied by some form of fried fish (chinam) or grilled tilapia and a very spicy condiment made from raw red and green chillies, onions and tomatoes (pepper sauce).[237] Banku and tilapia is a combo served in most restaurants.[237] Fufu is the most common exported Ghanaian dish and is a delicacy across the African diaspora.[237] Rice is an established staple meal across the country, with various rice based dishes serving as breakfast, lunch and dinner, the main variants are waakye, plain rice and stew (eight kontomire or tomato gravy), fried rice and jollof rice.[238]

Literature

Ghanaian literature is literature produced by authors from Ghana or in the Ghanaian diaspora. The tradition of literature starts with a long oral tradition, was influence heavily by western literature during colonial rule, and became prominent with a post-colonial nationalist tradition in the mid 20th century.[239][240][241] The current literary community continues with a diverse network of voices both within and outside the country today, including film, theatre, and modern digital formats such as blogging.[240][241]

The most prominent authors are novelists J. E. Casely Hayford, Ayi Kwei Armah and Nii Ayikwei Parkes, who gained international acclaim with the books Ethiopia Unbound (1911), The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born (1968) and Tail of the Blue Bird (2009), respectively.[242] In addition to novels, other literature arts such as theatre and poetry have also had a very good development and support at the national level with prominent playwrights and poets Joe de Graft and Efua Sutherland.[242]

The Ghanaian national literature radio programme and accompanying publication Voices of Ghana (1955-1957) was one of the earliest on the African continent, and helped establish the scope of the contemporary literary tradition in Ghana.[243] Scholarship of Anglo-phone Africa sometimes favors literatures from other geographies, such as the literature of Nigeria.[244]Clothing

During the 13th century, Ghanaians developed their unique art of adinkra printing. Hand-printed and hand-embroidered adinkra clothes were made and used exclusively by royalty for devotional ceremonies. Each of the motifs that make up the corpus of adinkra symbolism has a name and meaning derived from a proverb, a historical event, human attitude, ethology, plant life-form, or shapes of inanimate and man-made objects. The meanings of the motifs may be categorised into aesthetics, ethics, human relations, and concepts.[245] The Adinkra symbols have a decorative function as tattoos but also represent objects that encapsulate evocative messages that convey traditional wisdom, aspects of life, or the environment. There are many symbols with distinct meanings, often linked with proverbs. In the words of Anthony Appiah, they were one of the means in a pre-literate society for "supporting the transmission of a complex and nuanced body of practice and belief".[246]

Along with the adinkra cloth, Ghanaians use many cloth fabrics for their traditional attire.[247] The different ethnic groups have their own individual cloth. The most well known is the Kente cloth[247] Kente is a very important national costume and clothing, and these clothes are used to make traditional and modern Kente attire.[247] Different symbols and different colours mean different things.[247] Kente is the most famous of all the Ghanaian clothes.[247] Kente is a ceremonial cloth hand-woven on a horizontal treadle loom and strips measuring about 4 inches wide are sewn together into larger pieces of cloths.[247] Cloths come in various colours, sizes and designs and are worn during very important social and religious occasions.[247] In a cultural context, kente is more important than just a cloth as it is a visual representation of history and also a form of written language through weaving.[247] The term kente has its roots in the Akan word kɛntɛn which means a basket and the first kente weavers used raffia fibres to weave cloths that looked like kenten (a basket); and thus were referred to as kenten ntoma; meaning basket cloth.[247] The original Akan name of the cloth was nsaduaso or nwontoma, meaning "a cloth hand-woven on a loom"; however, "kente" is the most frequently used term today. Kente is also woven by the Ewe people (Ewe Kente) in the Volta Region. The main weaving centers are Agortime area and Agbozume. Agbozume has a vibrant kente market attracting patrons from all over west Africa and the diaspora.[247]

Contemporary Ghanaian fashion includes traditional and modern styles and fabrics and has made its way into the African and global fashion scene. The cloth known as African print fabric was created out of Dutch wax textiles. It is believed that in the late 19th century, Dutch ships on their way to Asia stocked with machine-made textiles that mimicked Indonesian batik stopped at many West African ports on the way. The fabrics did not do well in Asia. However, in West Africa—mainly Ghana where there was an already established market for cloths and textiles—the client base grew and it was changed to include local and traditional designs, colours and patterns to cater to the taste of the new consumers.[248] Today outside of Africa it is called "Ankara," and it has a client base well beyond Ghana and Africa as a whole. It is popular among Caribbean peoples and African Americans; celebrities such as Solange Knowles and her sister Beyoncé have been seen wearing African print attire.[249] Many designers from countries in North America and Europe are now using African prints, and they have gained a global interest.[250] British luxury fashion house Burberry created a collection around Ghanaian styles.[251] American musician Gwen Stefani has repeatedly incorporated African prints into her clothing line and can often be seen wearing it.[252] Internationally acclaimed Ghanaian-British designer Ozwald Boateng introduced African print suits in his 2012 collection.[253]

Music and dance

Music incorporates types of musical instruments such as the talking drum ensembles, Akan Drum, goje fiddle and koloko lute, court music, including the Akan Seperewa, the Akan atumpan, the Ga kpanlogo styles, and log xylophones used in asonko music.[254] African jazz was created by Kofi Ghanaba.[255] A form of secular music is highlife.[254] Highlife originated in the 19th and 20th centuries and spread throughout West Africa.[254]

In the 1990s, a genre of music was created incorporating the influences of highlife, Afro-reggae, dancehall and hip hop.[254] This hybrid was called hiplife.[254]

There are dances for occasions.[256] Dances for celebrations include the Adowa, Kpanlogo, Azonto, Klama, Agbadza, Borborbor and Bamaya.[256] The Nana Otafrija Pallbearing Services, also known as the Dancing Pallbearers, come from the coastal town of Prampram. The group was featured in a BBC feature story in 2017, and footage from the story became part of an Internet meme in the wake of the COVID-19 world pandemic.[257]

Media

Chapter 12 of the 1992 Constitution of Ghana guarantees freedom of the press and independence of the media, while Chapter 2 prohibits censorship.[258] Post-independence, private outlets closed during the military governments, and media laws prevented criticism of government.[259] Press freedoms were restored in 1992, and after the election in 2000 of Kufuor, the tensions between the private media and government decreased. Kufuor supported press freedom and repealed a libel law, and maintained that the media had to act responsibly.[260] The media have been described as "one of the most unfettered" in Africa.[261]

In 1948, the Gold Coast Film Unit was set up in the Information Services Department.[262]

Architecture

There are 2 types of construction: the series of adjacent buildings in an enclosure around a common, and the round huts with grass roof.[263] The round huts with grass roof architecture are situated in the northern regions, while the series of adjacent buildings are in the southern regions. Postmodern architecture and high-tech architecture buildings are in the southern regions, while heritage sites are evident in the more than 30 forts and castles in the country, such as Fort William and Fort Amsterdam. Ghana has museums that are situated inside castles, and 2 are situated inside a fort.[264] The Military Museum and the National Museum organise temporary exhibitions.[264]

Ghana has museums that show an in-depth look at specific regions. There are a number of museums that provide insight into the traditions and history of the geographical areas.[264] The Cape Coast Castle Museum and St. Georges Castle (Elmina Castle) Museum offer guided tours. The Museum of Science and Technology provides its visitors with a look into the domain of scientific development, through exhibits of objects of scientific and technological interest.[264]

Sports

Association football is the top spectator sport in Ghana.[265] Ghana has won the Africa Cup of Nations four times, the FIFA U-20 World Cup once, and has participated in three consecutive FIFA World Cups in 2006, 2010, and 2014.[265] The International Federation of Football History and Statistics crowned Asante Kotoko SC as the African club of the 20th century.[266]

Ghana competes in the Commonwealth Games, sending athletes in every edition since 1954 (except for the 1986 games). Ghana has won 57 medals at the Commonwealth Games, including 15 gold, with all but one of their medals coming in athletics and boxing. The country has also produced a number of boxers, including Azumah Nelson a three-time world champion,[267][268] Nana Yaw Konadu also a three-time world champion,[268] Ike Quartey,[268] and Joshua Clottey.[268]

References

- "Language and Religion". Ghana Embassy. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

English is the official language of Ghana and is universally used in schools in addition to nine other local languages. The most widely spoken local languages are Dagbanli, Ewe, Ga and Twi.

- "Ghana – 2010 Population and Housing Census" (PDF). Government of Ghana. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "2021 PHC General Report Vol 3C, Background Characteristics" (PDF). Ghana Statistical Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 December 2021.

- "Ghana country profile". BBC News. 17 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- "Ghana". The World Factbook (2023 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Ghana)". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. 10 October 2023. Retrieved 14 October 2023.

- "GINI index (World Bank estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 25 January 2019. Retrieved 14 July 2021.

- "Human Development Report 2020" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 15 December 2020. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2020.

- "Ghana country profile". BBC News. 11 December 2020. Archived from the original on 26 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- Jackson, John G. (2001) Introduction to African Civilizations, Citadel Press, p. 201, ISBN 0-8065-2189-9.

- "Ghana country profile". BBC News. 17 October 2023. Retrieved 17 October 2023.

- Ghana a country to study. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data. 1995. p. 63.

- Meyerowitz, Eva L. R. (1975). The Early History of the Akan States of Ghana. Red Candle Press. ISBN 9780608390352.

- Danver, Steven L (10 March 2015). Native Peoples of the World: An Encyclopedia of Groups, Cultures and Contemporary Issues. Routledge. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-317-46400-6. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- "Asante Kingdom". Afrika-Studiecentrum, Leiden. 15 June 2002. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- Video: A New Nation: Gold Coast becomes Ghana In Ceremony, 1957/03/07 (1957). Universal Newsreel. 1957. Archived from the original on 28 January 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "First For Sub-Saharan Africa". BBC. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- "Exploring Africa – Decolonization". Exploring Africa - Michigan State University. Archived from the original on 2 June 2013. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- Ateku, Abdul-Jalilu (7 March 2017). "Ghana is 60: An African success story with tough challenges ahead". The Conversation. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2021.

- "2020 Population Projection by Sex, 2010–2020". Ghana Statistical Service. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- "Ghana". CIA World FactBook. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- Kacowicz, Arie M. (1998). Zones of Peace in the Third World: South America and West Africa. SUNY Press. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-7914-3957-9. Archived from the original on 4 April 2023. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- "Ghana-US relations". United States Department of State. 13 February 2013. Archived from the original on 5 April 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Pre-Colonial Period". Ghanaweb.com. Archived from the original on 23 November 2010. Retrieved 13 December 2010.

- "Tradition and Religion in Africa: Exploring the Changing Roles of the Tindana in Dagbon".

- W, Jessica (15 November 2011). "Invasion of the Peoples of the North". GhanaNation. Archived from the original on 8 July 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- Curtis M. (19 November 2011). "Ghana Articles: Dagomba". GhanaNation.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2014. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- "Dagomba: Background". BristolDrumming. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- "Mamprusi". Sim.org. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2014.

- "The Mossi Kingdoms of West Africa - Right for Education". 25 January 2018. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "Bouna | African kingdom | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "Science and Technology in 18th Century Moliyili ) Dagomba) and the Timbuktiu Intellectual Tradition".

- Lauer, Helen (November 2007). "Depreciating African Political Culture". Journal of Black Studies. 38 (2): 288–307. doi:10.1177/0021934706286905. ISSN 0021-9347.

- "Dagbanli Ajami and Arabic Manuscripts of Northern Ghana". open.bu.edu. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "Female Chiefs in Dagbon Traditional Area: Role and Challenges in the Northern Region of Ghana" (PDF).

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for. "Refworld | Ghana: Information about the Dagomba tribe in Ghana". Refworld. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "The Yaa-Naa". www.adrummerstestament.com. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "Jan 20: In Yendi, the Yaa Naa, GundoNaa and Babatu – Interim on Slavery: Tamale-Ghana 2020". 3 February 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "German Colonialism in West Africa: Implications for German-West African Partnership in Development | H-Soz-Kult. Kommunikation und Fachinformation für die Geschichtswissenschaften | Geschichte im Netz | History in the web". H-Soz-Kult. Kommunikation und Fachinformation für die Geschichtswissenschaften (in German). 13 October 2023. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "Different Ideas of Borders and Border Construction in Northern Ghana: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives".

- Pukariga, Dasana (2005). "Dagbon recalling history, the battle of Adibo".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "The Battle of Adibo fought in 1896". Sanatu Zambang. 20 April 2020. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- "Pre-European Mining at Ashanti, Ghana" (PDF) (PDF). Pdmhs.com. October 1996. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 November 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- Tvedten, Ige; Hersoug, Bjørn (1992). Fishing for Development: Small Scale Fisheries in Africa. Nordic Africa Institute. pp. 60–. ISBN 978-91-7106-327-4. Archived from the original on 12 September 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Dennis M. Warren, The Techiman-Bono of Ghana: An Ethnography of an Akan Society. Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company, 1975.

- "A Short History of Ashanti Gold Weights". Rubens.anu.edu.au. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- "History of the Ashanti People". Modern Ghana. Archived from the original on 31 July 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- "History of Ghana". TonyX. Archived from the original on 1 May 2013. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- Levy, Patricia; Wong, Winnie (2010). Ghana. Marshall Cavendish. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-7614-4847-1.

- "History of Ghana". ghanaweb.com. Archived from the original on 15 December 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Emmer, Pieter C. (2018). The Dutch in the Atlantic Economy, 1580–1880: Trade, Slavery, and Emancipation (Variorum Collected Studies). Variorum Collected Studies (Book 614) (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-86078-697-9.

- "Bush Praises Strong Leadership of Ghanaian President Kufuor". iipdigital.usembassy.gov. 15 September 2008. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- MacLean, Iain (2001), Rational Choice and British Politics: An Analysis of Rhetoric and Manipulation from Peel to Blair, p. 76, ISBN 0-19-829529-4.

- Puri, Jyoti (2008). Encountering Nationalism. Wiley. pp. 76–. ISBN 978-0-470-77672-8. Archived from the original on 15 September 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Chronology of world history: a calendar of principal events from 3000 BC to AD 1973, Part 1973, Rowman & Littlefield, 1975, ISBN 0-87471-765-5.

- Ashanti Kingdom, Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2009, Archived 31 October 2009.

- Gocking, Roger (2005). The History of Ghana. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-0-313-31894-8. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- "Ghana flag and description". worldatlas.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- "5 Things To Know About Ghana's Independence Day". Africa.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- Oquaye, Mike (10 January 2018). "What is Republic Day in Ghana?". GhanaWeb. Archived from the original on 29 June 2018. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Mazrui, Ali (1966). "Nkrumah: The Leninist Czar". Transition (26): 9–17. doi:10.2307/2934320. ISSN 0041-1191. JSTOR 2934320.

- Kilson, Martin L. (1963). "Authoritarian and Single-Party Tendencies in African Politics". World Politics. 15 (2): 262–294. doi:10.2307/2009376. ISSN 1086-3338. JSTOR 2009376. S2CID 154624186. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- Bretton, Henry L. (1958). "Current Political Thought and Practice in Ghana*". American Political Science Review. 52 (1): 46–63. doi:10.2307/1953012. ISSN 1537-5943. JSTOR 1953012. S2CID 145766298. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- "Ghana's Kwame Nkrumah: visionary, authoritarian ruler and national hero". Deutsche Welle. 2016. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- "Portrait of Nkrumah as Dictator". The New York Times. 3 May 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- "VII. The Reluctant Nation", One-Party Government in the Ivory Coast, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 219–249, 31 December 1964, doi:10.1515/9781400876563-012, ISBN 978-1-4008-7656-3

- "Of Nkrumah's Political Ideologies: Communism, Socialism, Nkrumaism". Ghana Web. 20 September 2006. Archived from the original on 25 July 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "When it was made a Holiday". Modern Ghana. 22 September 2012. Archived from the original on 25 September 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- David, Owusu-Ansah (1994). A Country Study: Ghana. La Verle Berry.

- "Ghana: Flight Lieutenant Jerry John Rawlings (J.J Rawlings)". Africa Confidential. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Rawlings: The legacy". BBC News. 1 December 2000. Archived from the original on 28 August 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Elections in Ghana". Africanelections.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Refugees, United Nations High Commissioner for (26 September 2000). "Refworld | Ghana: Conflict between the Konkomba and Nanumba tribes and the government response to the conflict (1994 – September 2000)". Refworld. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 8 January 2022.

- Kokutse, Francis (3 January 2009). "Opposition leader wins presidency in Ghana". USA Today. Associated Press. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Emmanuel Gyimah-Boadi, "The 2008 Freedom House Survey: Another Step Forward for Ghana." Journal of Democracy 20.2 (2009): 138–152 excerpt Archived 18 August 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Atta Mills dies". The New York Times. 25 July 2012. Archived from the original on 9 July 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- "Ghanaian President John Dramani Mahama sworn in". Sina Corp. 7 January 2013. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- "Ghana - Economy: Keep calm and carry on: A strong and stable democracy has been built over the years". Oxford Business Group. 2013. Archived from the original on 23 April 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- "BTI 2016: Ghana Country Report" (PDF). BTI Transformation Index. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 January 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2023.

- "What the world media is saying about Ghana's 2016 elections – YEN.COM.GH". yen.com.gh. 7 December 2016. Archived from the original on 8 December 2016. Retrieved 7 December 2016.

- "2016 Presidential Results". Ghana Electoral Commission. Archived from the original on 19 May 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- "Ghana election: Nana Akufo-Addo re-elected as president". BBC News. 9 December 2020. Archived from the original on 9 December 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2021.

- "Planting of Five Million Tres on 11th June, 2021 the Green Ghana in the Bosomtwe Constituency | Bosomtwe District Assembly". www.bosomtwe.gov.gh. Archived from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 16 February 2022.

- "Ghana: Geography Physical". photius.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013., "Ghana: Location and Size". photius.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- "Ghana". August 2023.

- "Ghana low plains". photius.com. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- Grantham, H. S.; Duncan, A.; Evans, T. D.; Jones, K. R.; Beyer, H. L.; Schuster, R.; Walston, J.; Ray, J. C.; Robinson, J. G.; Callow, M.; Clements, T.; Costa, H. M.; DeGemmis, A.; Elsen, P. R.; Ervin, J.; Franco, P.; Goldman, E.; Goetz, S.; Hansen, A.; Hofsvang, E.; Jantz, P.; Jupiter, S.; Kang, A.; Langhammer, P.; Laurance, W. F.; Lieberman, S.; Linkie, M.; Malhi, Y.; Maxwell, S.; Mendez, M.; Mittermeier, R.; Murray, N. J.; Possingham, H.; Radachowsky, J.; Saatchi, S.; Samper, C.; Silverman, J.; Shapiro, A.; Strassburg, B.; Stevens, T.; Stokes, E.; Taylor, R.; Tear, T.; Tizard, R.; Venter, O.; Visconti, P.; Wang, S.; Watson, J. E. M. (2020). "Anthropogenic modification of forests means only 40% of remaining forests have high ecosystem integrity – Supplementary Material". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 5978. Bibcode:2020NatCo..11.5978G. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-19493-3. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 7723057. PMID 33293507.

- "Top 10 biggest dams". Water Technology. 29 September 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2022. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- "Profile of Major Rivers in Ghana" (PDF). Ghana Maritime Authority. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 December 2017. Retrieved 5 December 2021.

- Hinson, Tamara (28 August 2014). "11 of the world's most unusual surf spots". edition.cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- "UNDP Climate Change Country Profile: Ghana". ncsp.undp.org. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

- "Ghana". Climatelinks. Archived from the original on 7 April 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Climate Risk Profile: Ghana". Climatelinks. USAID. January 2017. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "NDC Registry(interim)". Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- "Government and Politics". A Country Study: Ghana Archived 13 July 2012 at archive.today (La Verle Berry, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (November 1994). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Lcweb2.loc.gov Archived 10 July 2012 at archive.today

- "Foreignpolicy.com – Failed States List 2012". 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Corruption Perceptions Index 2012". Transparency International Corruption Perception Index. 2012. Archived from the original on 28 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- Agyeman-Duah, Baffour. "Curbing Corruption and Improving Economic Governance: The Case of Ghana" (PDF). Ghana Center for Democratic Development. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2008. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Mo Ibrahim Foundation – 2012 Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG)". Moibrahimfoundation.org. 2012. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Official page of Nations Permanent Mission of Ghana to the United Nations". United Nations. 20 September 2011. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "US Vice President Kamala Harris' full speech upon arrival in Ghana - MyJoyOnline.com". www.myjoyonline.com. 26 March 2023. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- "Hu Jintao Holds Talks with President of Ghana Mills". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China. 20 September 2010. Archived from the original on 27 June 2012. Retrieved 4 January 2012.

- Deng, Shasha (12 November 2011). "Visiting senior Chinese official lauds Ghana for political stability, national unity". Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "Ahmadinejad: Iran's populist and pariah leaves the stage". BBCNews. 4 June 2013. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Iranian leader Ahmadinejad's West Africa tour defended". BBC News. 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 22 September 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "CPP welcomes President Ahmadinejad visit to Ghana". Ghana News Agency. 18 April 2013. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Ghana welcomed Iran's President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad". iafrica.tv. 17 April 2013. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad To Visit Ghana". Government of Ghana. 2013. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Ghana .:. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform". sustainabledevelopment.un.org. Archived from the original on 17 May 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "Sustainable Development Goals | United Nations in Ghana". ghana.un.org. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- "SDGs implementation: Ghana will be a shinning example' – Akufo-Addo". Graphic Online. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Kilford, Christopher R. (2010), The Other Cold War: Canada's Military Assistance to the Developing World 1945–75 Archived 20 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Kingston, Ontario: Canadian Defence Academy Press, p. 138, ISBN 1-100-14338-6.

- Baynham, Simon (1988), The Military and Politics in Nkumrah's Ghana, Westview, Chapter 4, ISBN 0-8133-7063-9.

- "Defence". Ministry of Finance and Economic Planning. Archived from the original on 26 April 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Ghana's Regional Security Policy: Costs, Benefits and Consistency". Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre. p. 33. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "KAIPTC". Kofi Annan International Peacekeeping Training Centre. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Vision and Mission of the Ministry of Defence (MoD)". gaf.mil.gh. Ghana Armed Forces. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Real-time Analysis of African Political Violence" (PDF). Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project. May 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "The Ghana Police Service". mint.gov.gh. Archived from the original on 12 May 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Ghana Police Service sets up Marine Police Unit". modernghana.com. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2013.

- "Police Administration". ghanapolice.info. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 19 June 2013.

- "Ghana Prisons Service General Information". ghanaprisons.gov.gh. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- "Ghana – Death Penalty". handsoffcain.info. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- "Ghana Criminal Code and Courts". country-data.com. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2013.

- Perriello. "Promoting Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions in the Great Lakes". DIPNote. US Department of state. Archived from the original on 20 May 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Ghana hit by illegal drug trade". Gulf News. 28 September 2013. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- Gerra. "Illegal drug use on the rise in Africa". DW Made for minds. Deutsche Welle. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- "Ghana could be taken over by drug barons if". myjoyonline.com. 20 November 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- "Here are the 10 countries where homosexuality may be punished by death". The Washington Post. 16 June 2016. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- "The Global Divide on Homosexuality." Archived 3 November 2013 at the Wayback Machine Pew Research Center. 4 June 2013.

- "Ghana witch camps: Widows' lives in exile". BBC News. 1 September 2012. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Ghana". Vizocom – Satellite Internet and VSAT Solutions. Archived from the original on 8 June 2020. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- "Is Ghana the next African economic tiger?". standardmedia.co.ke. 4 September 2012. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2013.

- "BoG introduce Chinese Yuan onto the FX market". Bank of Ghana. 2013. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- Sy, Temesgen Deressa and Amadou (30 November 2001). "Ghana's Request for IMF Assistance". Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- Diao, Xinshen. Economic Importance of Agriculture for Sustainable Development and Poverty Reduction: Findings from a Case Study of Ghana (PDF). Global Forum on Agriculture 29–30 November 2010 – Policies for Agricultural Development, Poverty Reduction and Food Security. Paris. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- "Ghana – Gross Domestic Product" (PDF). statsghana.gov.gh. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- "A new era of transformation in Ghana" (PDF). ifpri.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2012. Retrieved 16 February 2012.: 12

- "New fuel for faster development". worldfolio.co.uk. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- "Ghana Market Update" (PDF). Intercontinental Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.: 13

- "Top-Performing African Stock Markets in 2013". africastrictlybusiness.com. 2013. Archived from the original on 21 March 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- "Is Ghana Entering A Sweet, Golden Era?". African Business. September 2011. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 10 May 2014.

- "Cocoa facts and figures - Kakaoplattform". www.kakaoplattform.ch. Archived from the original on 17 June 2022. Retrieved 20 August 2022.

- Forrest, Paul (September 2011). Ghana Market Update (PDF). Intercontinental Bank. p. 13. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2012. Retrieved 26 March 2012.

- "Ghana's Jubilee oil field nears output plateau -operator". Reuters. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- "The Top 5 Countries for ICT4D in Africa". ictworks.org. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- Kofi Adu Domfeh (13 April 2013). "Ghana's model vehicle unveiled by Suame Magazine artisans". Modernghana.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Ghana's model car attracts Dutch government support". Myjoyonline.gh. 15 July 2013. Archived from the original on 23 September 2013. Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- "Ghana to Sell Sustainable Bonds for up to $1 Billion by July". Bloomberg.com. 25 May 2021. Archived from the original on 18 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Ghana Mulls Africa's First Social Bonds with $2 Billion Sale". Bloomberg.com. 5 July 2021. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- "Ghana plans to issue Africa's first social bonds with $2B sale". www.aljazeera.com. Archived from the original on 6 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- "Five Countries to Watch". individual.troweprice.com. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2013.

- "Africa". Aluworks.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- Clark, Nancy L. "Petroleum Exploration". A Country Study: Ghana Archived 13 July 2012 at archive.today (La Verle Berry, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (November 1994). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Lcweb2.loc.gov Archived 10 July 2012 at archive.today

- "Ghana leader: Oil reserves at 3B barrels". Yahoo News. 22 December 2007. Archived from the original on 26 December 2007. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- McLure, Jason. Ghana Oil Reserves to Be 5 billion barrels (790,000,000 m3) in 5 years as fields develop Archived 29 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Bloomberg Television, 1 December 2010.

- Aklorbortu, Moses Dotsey (13 May 2013). "Atuabo gas project to propel more growth". Daily Graphic. Archived from the original on 3 May 2014. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- "Ghana: Why Privatise Ghana Oil?". allafrica.com. Archived from the original on 29 September 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- "Ghana Gold Production". CEIC Data. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Whitehouse, David (8 October 2019). "Ghana now Africa's largest gold producer, but reforms await". The Africa Report. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Ghana Mineral and Mining Sector Investment and Business Guide. International Business Publications, USA. 7 February 2007. ISBN 978-1-4330-1775-9. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "Ghana". Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- Ghana Mineral and Mining Sector Investment and Business Guide. 2007. ISBN 978-1-4330-1775-9. Retrieved 24 June 2013.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "Ghana Minerals and Mining Act". ghanalegal.com. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "I've been named 'Mr Dumsor' in Ghana – Prez Mahama tells Ghanaians in Germany – See more at". Graphic Online. Graphic Communications Group Ltd (GCGL). 21 January 2015. Archived from the original on 24 April 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- Agbenyega, E. (10 April 2014). "Ghana's power crisis: What about renewable energy?". graphic.com.gh. Archived from the original on 1 July 2015. Retrieved 8 February 2015.