Ibn Taymiyya

Ibn Taymiyya (January 22, 1263 – September 26, 1328; Arabic: ابن تيمية), birth name Taqī ad-Dīn ʾAḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd al-Salām al-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī (Arabic: تقي الدين أحمد بن عبد الحليم بن عبد السلام النميري الحراني)[11] was a Sunni Muslim ʿālim,[12][13][14] muhaddith, judge,[15][16] proto-Salafist theologian,[lower-alpha 1] ascetic, and iconoclastic theologian.[17][14] He is known for his diplomatic involvement with the Ilkhanid ruler Ghazan Khan and for his involvement at the Battle of Marj al-Saffar which ended the Mongol invasions of the Levant.[18] A legal jurist of the Hanbali school, Ibn Taymiyya's condemnation of numerous folk practices associated with saint veneration and visitation of tombs made him a contentious figure with rulers and scholars of the time, and he was imprisoned several times as a result.[19]

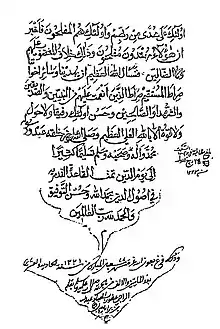

Ibn Taymiyya ابن تيمية | |

|---|---|

Ibn Taymiyyah's name with "Shaykh ul-Islam" written in Arabic | |

| Title | Shaykh al-Islām |

| Personal | |

| Born | 10 Rabi' al-awwal 661 AH, or January 22, 1263, CE |

| Died | 20 Dhu al-Qi'dah 728 AH, or September 26, 1328 (aged 64–65) |

| Religion | Islam |

| Era | Late High Middle Ages or Crisis of the Late Middle Ages |

| Denomination | Sunni |

| Jurisprudence | Hanbali[1][2] |

| Creed | Athari[3][4][5][6][7][8] |

| Alma mater | Madrasa Dar al-Hadith as-Sukariya |

| Muslim leader | |

| Arabic name | |

| Personal (Ism) | Ahmad (أحمد) |

| Patronymic (Nasab) | Ibn Abd al-Halim ibn Abd as-Salam ibn Abd Allah ibn al-Khidr ibn Muhammad ibn al-Khidr ibn Ibrahim ibn Ali ibn Abd Allah (بن عبد الحليم بن عبد السلام بن عبد الله بن الخضر بن محمد بن الخضر بن إبراهيم بن علي بن عبد الله) |

| Teknonymic (Kunya) | Abu al-Abbas (أبو العباس) |

| Toponymic (Nisba) | al-Harrani[10] (الحراني) |

| Part of a series on:

Salafi movement |

|---|

|

|

|

A polarizing figure in his own times and in the centuries that followed,[20][21] Ibn Taymiyya has emerged as one of the most influential medieval scholars in late modern Sunni Islam.[19] He was also noteworthy for engaging in fierce religious polemics that attacked various schools of Kalām (speculative theology); primarily Ash'arism and Maturidism, while defending the doctrines of Athari school. This prompted rival clerics and state authorities to accuse Ibn Taymiyya and his disciples of tashbīh (anthropomorphism); which eventually led to the censoring of his works and subsequent incarceration.[22][23][24]

Nevertheless, Ibn Taymiyya's numerous treatises that advocates for "creedal Salafism" (al-salafiyya al-iʿtiqādīyya), based on his scholarly interpretations of the Qur'an and the Sunnah, constitute the most popular classical reference for later Salafi movements.[25] Ibn Taymiyya asserted through his treatises that there is no contradiction between reason and revelation,[26] and denounced the usage of philosophy as a pre-requisite in seeking religious truth.[27] As a cleric who viewed Shi'ism as a source of corruption in Muslim societies; Ibn Taymiyya was also known for virulent anti-Shia polemics through treatises like Minhaj al-Sunna, wherein he denounced Imami Shi'ite creed as heretical. Ibn Taymiyya declared a fatwa to wage Jihad against the Shi'ites of Kisrawan and personally fought in the Kisrawan campaigns, accusing Shi'ites of acting as the fifth-columinists of Frank Crusaders and Mongol Ilkhanates.[28]

Within recent history, Ibn Taymiyya has been widely regarded as a major scholarly influence in revolutionary Islamist movements, such as Salafi-Jihadism.[29][30][31] Major aspects of his teachings such as upholding the pristine monotheism of the early Muslim generations and campaigns to uproot what he regarded as shirk (idolatry); had a profound influence on Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab, the founder of the Wahhabist reform movement formed in Arabian Peninsula, and on other later Sunni scholars.[2][32] Lebanese Salafi theologian Muhammad Rashid Rida (d. 1935 C.E/ 1354 A.H), one of the major modern proponents of his works, designated Ibn Taymiyya as the Mujaddid (renewer) of the Islamic 7th century of Hijri year.[33][34] Ibn Taymiyya's doctrinal positions, such as his Takfir (declaration of unbelief) of the Mongol Ilkhanates, allowing jihad against other self-professed Muslims, were referenced by Islamic social movements such as the Muslim Brotherhood to justify social uprisings against contemporary governments across the Muslim world.[35][36][37]

Name

Ibn Taymiyya's full name is Taqiy al-Din 'Abu al-Abbas 'Aḥmad ibn ʿAbd al-Ḥalīm ibn ʿAbd as-Salām ibn ʿAbdullāh ibn al-Khiḍr ibn Muḥammad ibn al-Khiḍr ibn ʾIbrāhīm ibn ʿAli ibn ʿAbdullāh an-Numayrī al-Ḥarrānī[10] (Arabic: أحمد بن عبد الحليم بن عبد السلام بن عبد الله بن الخضر بن محمد بن الخضر بن إبراهيم بن علي بن عبد الله النميري الحراني).

Ibn Taymiyya's (ابن تيمية) name is unusual in that it is derived from a female member of his family as opposed to a male member, which was the normal custom at the time and still is now. The title "Taymiyyah" comes from the mother of his forefathers who was called Taymiyahh. She was an admonisher and he was ascribed to her and became known through the name, "Ibn Taymiyahh".[12] Taymiyyah was a prominent woman, famous for her scholarship and piety and the name Ibn Taymiyya was taken up by many of her male descendants.[10]

Overview

Ibn Taymiyya had a simple life, most of which he dedicated to learning, writing, and teaching. He never married nor did he have a female companion throughout his years.[38][39] Al-Matroudi says that this may be why he was able to engage fully with the political affairs of his time without holding any official position such as that of a judge.[40] An offer of an official position was made to him but he never accepted.[40] His life was that of a religious scholar and a political activist.[39] In his efforts he was persecuted and imprisoned on six occasions[41] with the total time spent inside prison coming to over six years.[39][42] Other sources say that he spent over twelve years in prison.[40] His detentions were due to certain elements of his creed and his views on some jurisprudential issues.[38] However, according to Yahya Michot, "the real reasons were more trivial". Michot gives five reasons as to why Ibn Taymiyya was imprisoned, they being: not complying with the "doctrines and practices prevalent among powerful religious and Sufi establishments, an overly outspoken personality, the jealousy of his peers, the risk to public order due to this popular appeal and political intrigues."[42] Baber Johansen, a professor at the Harvard Divinity School, says that the reasons for Ibn Taymiyya's incarcerations were, "as a result of his conflicts with Muslim mystics, jurists, and theologians, who were able to persuade the political authorities of the necessity to limit Ibn Taymiyya's range of action through political censorship and incarceration."[43]

Ibn Taymiyya's own relationship, as a religious scholar, with the ruling apparatus was not always amicable.[42] It ranged from silence to open rebellion.[42] On occasions when he shared the same views and aims as the ruling authorities his contributions were welcomed, but when Ibn Taymiyya went against the status quo, he was seen as "uncooperative", and on occasions spent much time in prison.[44] Ibn Taymiyya's attitude towards his own rulers was based on the actions of Muhammad's companions when they made an oath of allegiance to him as follows; "to obey within obedience to God, even if the one giving the order is unjust; to abstain from disputing the authority of those who exert it; and to speak out the truth, or take up its cause without fear in respect of God, of blame from anyone."[42]

Early years

Family

Ibn Taymiyya was born in Harran, to a family of traditional Hanbali scholars. Ibn Taymiyya had Arab and Kurdish lineages; through his Arab father and by way of his mother, who was of Kurdish descent.[45][46] Ibn Taymiyya's father, Shihab al-Din Abd al-Halim Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1284 C.E/ 682 A.H), had the Hanbali chair in Harran and later at the Umayyad Mosque. At the time, Harran was a part of the Mamluk Sultanate, near what is today the border of Syria and Turkey, currently in Şanlıurfa Province.[47] At the beginning of the Islamic period, Harran was located in the land of the Mudar tribe (Diyar Mudar).[48] Before its destruction by the Mongols, Harran was also well known since the early days of Islam for its Hanbali school and tradition,[49] to which Ibn Taymiyya's family belonged.[47] His grandfather, Abu al-Barkat Majd ad-Din Ibn Taymiyya al-Hanbali (d. 1255) and his uncle, Fakhr al-Din (d. 1225) were reputable scholars of the Hanbali school of law.[19] Likewise, the scholarly achievements of his father were also well known.

Education

In 1269, aged seven, Ibn Taymiyya, left Harran together with his father and three brothers. The city was completely destroyed by the ensuing Mongol invasion.[50][19] Ibn Taymiyya's family moved and settled in Damascus, Syria, which at the time was ruled by the Mamluk Sultanate.

In Damascus, his father served as the director of the Sukkariyya Madrasa, a place where Ibn Taymiyya also received his early education.[51] Ibn Taymiyya acquainted himself with the religious and secular sciences of his time. His religious studies began in his early teens, when he committed the entire Qur'an to memory and later on came to learn the Islamic disciplines of the Qur'an.[50] From his father he learnt the religious science of fiqh (jurisprudence) and usul al-fiqh (principles of jurisprudence).[50] Ibn Taymiyya learnt the works of Ahmad ibn Hanbal, al-Khallal, Ibn Qudamah and also the works of his grandfather, Abu al-Barakat Majd ad-Din.[19] His study of jurisprudence was not limited to the Hanbali tradition but he also learnt the other schools of jurisprudence.[19]

The number of scholars under which he studied hadith is said to number more than two hundred,[38][50][52] four of whom were women.[53] Those who are known by name amount to forty hadith teachers, as recorded by Ibn Taymiyya in his book called Arba`un Hadithan.[54] Serajul Haque says, based on this, Ibn Taymiyya started to hear hadith from the age of five.[54] One of his teachers was the first Hanbali Chief Justice of Syria, Shams ud-Din Al-Maqdisi who held the newly created position instituted by Baibars as part of a reform of the judiciary.[19] Al-Maqdisi later on, came to give Ibn Taymiyya permission to issue Fatawa (legal verdicts) when he became a mufti at the age of 17.[38][42][55]

Ibn Taymiyya's secular studies led him to devote attention to Arabic language and Arabic literature by studying Arabic grammar and lexicography under Ali ibn `Abd al-Qawi al-Tufi.[50][56] He went on to master the famous book of Arabic grammar, Al-Kitab, by the Persian grammarian Sibawayhi.[50] He also studied mathematics, algebra, calligraphy, theology (kalam), philosophy, history and heresiography.[38][42][19][57] Based on the knowledge he gained from history and philosophy, he used to refute the prevalent philosophical discourses of his time, one of which was Aristotelian philosophy.[38] Ibn Taymiyya learnt about Sufism and stated that he had reflected on the works of; Sahl al-Tustari, Junayd of Baghdad, Abu Talib al-Makki, Abdul-Qadir Gilani, Abu Hafs Umar al-Suhrawardi and Ibn Arabi.[19] At the age of 20 in the year 1282, Ibn Taymiyya completed his education.[58]

Life as a scholar

After his father died in 1284, he took up the then vacant post as the head of the Sukkariyya madrasa and began giving lessons on Hadith.[42][19][59] A year later he started giving lessons, as chair of the Hanbali Zawiya on Fridays at the Umayyad Mosque, on the subject of tafsir (exegesis of Qur'an).[42][56][60] In November 1292, Ibn Taymiyya performed the Hajj and after returning 4 months later, he wrote his first book aged twenty nine called Manasik al-Hajj (Rites of the Pilgrimage), in which he criticized and condemned the religious innovations he saw take place there.[19][51] Ibn Taymiyya represented the Hanbali school of thought during this time. The Hanbali school was seen as the most traditional school out of the four legal systems (Hanafi, Maliki and Shafii) because it was "suspicious of the Hellenist disciplines of philosophy and speculative theology."[51] He remained faithful throughout his life to this school, whose doctrines he had mastered, but he nevertheless called for ijtihad (independent reasoning by one who is qualified) and discouraged taqlid.[58]

Relationship with the authorities

Ibn Taymiyya's emergence in the public and political spheres began in 1293 when he was 30 years old, when the authorities asked him to issue a fatwa (legal verdict) on Assaf al-Nasrani, a Christian cleric who was accused of insulting Muhammad.[44][19][61] He accepted the invitation and delivered his fatwa, calling for the man to receive the death penalty.[44] Despite the fact that public opinion was very much on Ibn Taymiyya's side,[51] the Governor of Syria attempted to resolve the situation by asking Assaf to accept Islam in return for his life, to which he agreed.[51] This resolution was not acceptable to Ibn Taymiyya who then, together with his followers, protested against it outside the governor's palace, demanding that Assaf be put to death,[51] on the grounds that any person—Muslim or non-Muslim—who insults Muhammad must be killed.[42][51] His unwillingness to compromise, coupled with his attempt to protest against the governor's actions, resulted in him being punished with a prison sentence, the first of many such imprisonments which were to come.[19] The French orientalist Henri Laoust says that during his incarceration, Ibn Taymiyya "wrote his first great work, al-Ṣārim al-maslūl ʿalā shātim al-Rasūl (The Drawn Sword against those who insult the Messenger)."[19] Ibn Taymiyya, together with the help of his disciples, continued with his efforts against what, "he perceived to be un-Islamic practices" and to implement what he saw as his religious duty of commanding good and forbidding wrong.[42][62] Yahya Michot says that some of these incidences included: "shaving children's heads", leading "an anti-debauchery campaign in brothels and taverns", hitting an atheist before his public execution, destroying what was thought to be a sacred rock in a mosque, attacking astrologers and obliging "deviant Sufi Shaykhs to make public acts of contrition and adhere to the Sunnah."[42] Ibn Taymiyya and his disciples used to condemn wine sellers and they would attack wine shops in Damascus by breaking wine bottles and pouring them onto the floor.[60]

A few years later in 1296, he took over the position of one of his teachers (Zayn al-Din Ibn al-Munadjdjaal), taking the post of professor of Hanbali jurisprudence at the Hanbaliyya madrasa, the oldest such institution of this tradition in Damascus.[19][51][63] This is seen by some to be the peak of his scholarly career.[51] The year when he began his post at the Hanbaliyya madrasa, was a time of political turmoil. The Mamluk sultan Al-Adil Kitbugha was deposed by his vice-sultan Al-Malik al-Mansur Lajin who then ruled from 1297 to 1299.[64] Lajin desired to commission an expedition against the Christians of the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia who formed an alliance with the Mongol Empire and participated in the military campaign which lead to the destruction of Baghdad, the capital of the Abbasid Caliphate, and the destruction of Harran, the birthplace of Ibn Taymiyya, for that purpose, he urged Ibn Taymiyya to call the Muslims to Jihad.[19][51]

In 1298, Ibn Taymiyya wrote his explanation for the ayat al-mutashabihat (the unclear verses of the Qur'an) titled Al-`Aqidat al-Hamawiyat al-Kubra (The creed of the great people of Hama).[65][66] The book is about divine attributes and it served as an answer to a question from the city of Hama, Syria.[65][66] At that particular time Ash'arites held prominent positions within the Islamic scholarly community in both Syria and Egypt, and they held a certain position on the divine attributes of God.[65] Ibn Taymiyya in his book strongly disagreed with their views and this heavy opposition to the common Ash'ari position, caused considerable controversy.[65]

Once more, Ibn Taymiyya collaborated with the Mamluks in 1300, when he joined the punitive expedition against the Alawites and Shiites, in the Kasrawan region of the Lebanese mountains.[44][19] Ibn Taymiyya believed that the Alawites were "more heretical than Jews and Christians",[67][68] and according to Carole Hillenbrand, the confrontation with the Alawites occurred because they "were accused of collaborating with Christians and Mongols."[44] Ibn Taymiyya had further active involvements in campaigns against the Mongols and their alleged Alawite allies.[51]

In 1305, Ibn Taymiyya took part in a second military offensive against the Alawites and the Isma`ilis[69] in the Kasrawan region of the Lebanese mountains where they were defeated.[19][67][70] The majority of the Alawis and Ismailis eventually converted to Twelver Shiism and settled in south Lebanon and the Bekaa valley, with a few Shia pockets that survived in the Lebanese mountains.[71][72]

Involvement in the Mongol invasions

First invasion

The first invasion took place between December 1299 and April 1300 due to the military campaign by the Mamluks against the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia who were allied with the Mongols.[73] Due to the Mongol legal system that neglected sharia and implemented Yassa; Ibn Taymiyya had declared Takfir upon the Ilkhanid regime and its armies for ruling by man-made laws, despite these laws being rarely enforced in Muslim majority regions in an extensive manner.[74][75] Openly rejecting Ghazan Khan's claim to "pādishāh al-islām" (King of Islam), a title which Ghazan took to legitimise his military campaigns, Ibn Taymiyya denounced him as an "infidel king" and issued numerous fatwas condemning the political order of the Tatars.[76] The Ilkhanate army managed to defeat the Mamluk Sultanate in The Third Battle of Homs and reach Damascus by the end of December 1299. Fearful of Mongol atrocities, many scholars, intellectuals and officers began to flee Damascus in panic. Ibn Taymiyya was one of those clerics who stood firm alongside the vulnerable Damascus citizens and called for an uncompromising and heroic resistance to the Tatar invaders. Ibn Taymiyya drew parallels of their crisis with the Riddah wars (Apostate wars) fought by the first Muslim Caliph, Abubakr, against the renegade Arabian tribes that abandoned sharia. Ibn Taymiyya severely rebuked those Muslims escaping in the face of Mongol onslaught and compared their state to the withdrawal of Muslims in the Battle of Uhud.[73][77] In a passionate letter to the commander of the Damascene Citadel, Ibn Taymiyya appealed:

"Until there stands even a single rock, do everything in your power to not surrender the castle. There is great benefit for the people of Syria. Allah declared it a sanctuary for the people of Shām—where it will remain a land of faith and sunna until the descent of the Prophet Jesus.”[78]

Despite political pressure, Ibn Taymiyya's directives were heeded by the Mamluk officer and Mongol negotiations to surrender the Citadel stalled. Shortly after, Ibn Taymiyya and a number of his acolytes and pupils took part in a counter-offensive targeting various Shia tribes allied to the Mongols in the peripheral regions of the city; thereby repelling the Mongol attack.[78] Ibn Taymiyya went with a delegation of Islamic scholars to talk to Ghazan Khan, who was the Khan of the Mongol Ilkhanate of Iran, to plead clemency.[73][79] By early January 1300, the Mongol allies, the Armenians and Georgians, had caused widespread damage to Damascus and they had taken Syrian prisoners.[73] The Mongols effectively occupied Damascus for the first four months of 1303.[62] Most of the military had fled the city, including most of the civilians.[62] Ibn Taymiyya however, stayed and was one of the leaders of the resistance inside Damascus and he went to speak directly to the Ilkhan, Mahmud Ghazan, and his vizier Rashid al-Din Tabib.[42][62] He sought the release of Muslim and dhimmi prisoners which the Mongols had taken in Syria, and after negotiation, secured their release.[42][51]

Second invasion

The second invasion lasted between October 1300 and January 1301.[73] Ibn Taymiyya at this time began giving sermons on jihad at the Umayyad mosque.[73] As the civilians began to flee in panic; Ibn Taymiyya pronounced fatwas declaring the religious duty upon Muslims to fight the Mongol armies to death, inflict a massive defeat and expel them from Syria in its entirety.[80] Ibn Taymiyya also spoke to and encouraged the Governor of Damascus, al-Afram, to achieve victory over the Mongols.[73] He became involved with al-Afram once more, when he was sent to get reinforcements from Cairo.[73] Narrating Ibn Taymiyya's fierce stance on fighting the Mongols, Ibn Kathir reports:

even if you see me on their side with a Qurʾan on my side, kill them immediately!

Third invasion and Takfir of Ilkhanate Allies

The year 1303 saw the third Mongol invasion of Syria by Ghazan Khan.[82][83] What has been called Ibn Taymiyya's "most famous" fatwā[84] was his third fatwa issued against the Mongols in the Mamluk's war. Ibn Taymiyya declared that jihad against the Mongol attack on the Malmuk sultanate was not only permissible, but obligatory.[59] The reason being that the Mongols could not, in his opinion, be true Muslims despite the fact that they had converted to Sunni Islam because they ruled using what he considered 'man-made laws' (their traditional Yassa code) rather than Islamic law or Sharia, whilst believing that the Yassa code was better than the Sharia law. Because of this, he reasoned they were living in a state of jahiliyyah, or pre-Islamic pagan ignorance.[29] Not only were Ilkhanate political elites and its military disbelievers in the eyes of Ibn Taymiyya; but anybody who joined their ranks were as guilty of riddah (apostasy) as them:

"Whoever joins them—meaning the Tatars—among commanders of the military and non-commanders, their ruling is the same as theirs, and they have apostatized from the laws [sharāʾiʿ]. If the righteous forbears [salaf] have called the withholders from charity apostates despite their fasting, praying, and not fighting the Muslims, how about those who became murderers of the Muslims with the enemies of Allah and His Messenger?”

The fatwa broke new Islamic legal ground because "no jurist had ever before issued a general authorization for the use of lethal force against Muslims in battle", and would later influence modern-day Jihadists in their use of violence against other Muslims whom they deemed as apostates.[18] In his legal verdicts issued to inform the populace, Ibn Taymiyya classified the Tatars and their advocates into four types:

- Kaafir Asli (i.e, those original non-Muslims fighting inTatar armies and never embraced Islam)

- Muslims of other ethincities who became apostates due to their alliance with Mongols

- Irreligious Muslims aligned with Ilkhanids whom Ibn Taymiyya analogized with renegade Arabian tribes of the Riddah wars

- Personally pious Muslims affiliated with the Mongol armies. Ibn Taymiyya harshly rebuked these people as the "most evil" faction; and argued that their piety was useless because of their decision to ally with non-Muslims who ruled by man-made laws. This rationale was also expanded to excommunicate those "court scholars" who vindicated the Tatar authorities[86]

Ibn Taymiyya called on the Muslims to jihad once again and personally participated in the Battle of Marj al-Saffar against the Ilkhanid army; leading his disciples in the field with a sword.[44][82][80] The battle began on April 20 of that year.[82] On the same day, Ibn Taymiyya declared a fatwa which exempted Mamluk soldiers from fasting during Ramadan so that they could preserve their strength.[44][19][82] Within two days the Mongols were severely crushed and the battle was won; thus ending Mongol control of Syria. These incidents greatly increased the scholarly prestige and social stature of Ibn Taymiyya amongst the masses, despite opposition from the establishment clergy. He would soon be appointed as the chief professor of the elite scholarly institute "Kāmiliyya Dār al-Haḍīth."[82][80]

Contemporary Impact

Ibn Taymiyya's three unprecedented fatwas (legal verdicts) that excommunicated the Ilkhanid authorities and their supporters as apostates over their neglect to govern by Sharia (Islamic law) and preference of the traditional Mongol imperial code of Yassa; would form the theological basis of 20th century Islamist and Jihadist scholars and ideologues. Reviving Ibn Taymiyya's fatwas during the late 20th-century, Jihadist ideologues like Sayyid Qutb, Abd al-Salam al-Faraj, Abdullah Azzam, Usama bin Laden, Ayman al-Zawahiri, etc. made public Takfir (excommunication) of contemporary governments of the Muslim world and called for their revolutionary overthrowal through armed Jihad.[87]

Imprisonment on charges of anthropomorphism

Ibn Taymiyya was a fervent polemicist who waged perpetual theological attacks against various religious sects such as the Sufis, Jahmites, Asha'rites, Shias, Falsafa etc., labelling them as heretics responsible for the crisis of Mongol invasions across the Islamic World.[88] He was imprisoned several times for conflicting with the prevailing opinions of the jurists and theologians of his day. A judge from the city of Wasit, Iraq, requested that Ibn Taymiyya write a book on creed. His subsequent creedal work, Al-Aqidah Al-Waasitiyyah, caused him trouble with the authorities.[43][56] Ibn Taymiyya adopted the view that God should be described as he was literally described in the Qur'an and in the hadith,[56] and that all Muslims were required to believe this because according to him it was the view held by the early Muslim community (salaf).[43] Within the space of two years (1305–1306) four separate religious council hearings were held to assess the correctness of his creed.[43]

The first hearing was held with Ash'ari scholars who accused Ibn Taymiyya of anthropomorphism.[43] At the time Ibn Taymiyya was 42 years old. He was protected by the then Governor of Damascus, Aqqush al-Afram, during the proceedings.[43] The scholars suggested that he accept that his creed was simply that of the Hanbalites and offered this as a way out of the charge.[43] However, if Ibn Taymiyya ascribed his creed to the Hanbali school of law then it would be just one view out of the four schools which one could follow rather than a creed everybody must adhere to.[43] Uncompromising, Ibn Taymiyya maintained that it was obligatory for all scholars to adhere to his creed.[43]

Two separate councils were held a year later on January 22 and 28, 1306.[43][19] The first council was in the house of the Governor of Damascus Aqqush al-Afram, who had protected him the year before when facing the Shafii scholars.[19] A second hearing was held six days later where the Indian scholar Safi al-Din al-Hindi found him innocent of all charges and accepted that his creed was in line with the "Qur'an and the Sunnah".[43][19] Regardless, in April 1306 the chief Islamic judges of the Mamluk state declared Ibn Taymiyya guilty and he was incarcerated.[43] He was released four months later in September.[43]

After his release in Damascus, the doubts regarding his creed seemed to have resolved but this was not the case.[19] A Shafii scholar, Ibn al-Sarsari, was insistent on starting another hearing against Ibn Taymiyya which was held once again at the house of the Governor of Damascus, Al-Afram.[19] His book Al-Aqidah Al-Waasitiyyah was still not found at fault.[19] At the conclusion of this hearing, Ibn Taymiyya and Ibn al-Sarsari were sent to Cairo to settle the problem.

Life in Egypt

His debate on anthropomorphism and his imprisonment

On the arrival of Ibn Taymiyya and the Shafi'ite scholar in Cairo in 1306, an open meeting was held.[70] The Mamluk sultan at the time was Al-Nasir Muhammad and his deputy attended the open meeting.[70] Ibn Taymiyya was found innocent.[70] Despite the open meeting, objections regarding his creed continued and he was summoned to the Citadel in Cairo for a munazara (legal debate), which took place on April 8, 1306. During the munazara, his views on divine attributes, specifically whether a direction could be attributed to God, were debated by the Indian scholar Safi al-Din al-Hindi, in the presence of Islamic judges.[89][19] Ibn Taymiyya failed to convince the judges of his position and so was incarcerated for the charge of anthropomorphism on the recommendation of al-Hindi.[89][19] Thereafter, he together with his two brothers were imprisoned in the Citadel of the Mountain (Qal'at al-Jabal), in Cairo until September 25, 1307.[90][19][89] He was freed due to the help he received from two amirs; Salar and Muhanna ibn Isa, but he was not allowed to go back to Syria.[19] He was then again summoned for a legal debate, but this time he convinced the judges that his views were correct and he was allowed to go free.[89]

His trial for intercession and his imprisonment

Ibn Taymiyya continued to face troubles for his views which were found to be at odds with those of his contemporaries. His strong opposition to what he believed to be religious innovations, caused upset among the prominent Sufis of Egypt including Ibn Ata Allah and Karim al-Din al-Amuli, and the locals who started to protest against him.[19] Their main contention was Ibn Taymiyya's stance on tawassul (intercession).[19] In his view, a person could not ask anyone other than God for help except on the Day of Judgement when intercession in his view would be possible. At the time, the people did not restrict intercession to just the Day of Judgement but rather they said it was allowed in other cases. Due to this, Ibn Taymiyya, now aged 45, was ordered to appear before the Shafi'i judge Badr al-Din in March 1308 and was questioned on his stance regarding intercession.[19] Thereafter, he was incarcerated in the prison of the judges in Cairo for some months.[19] After his release, he was allowed to return to Syria, should he so wish.[19] Ibn Taymiyya however stayed in Egypt for a further five years.

House arrest in Alexandria

1309, the year after his release, saw a new Mamluk sultan accede to the throne, Baibars al-Jashnakir. His reign, marked by economical and political unrest, only lasted a year.[19] In August 1309, Ibn Taymiyya was taken into custody and placed under house arrest for seven months in the new sultan's palace in Alexandria.[19] He was freed when al-Nasir Muhammad retook the position of sultan on March 4, 1310.[19] Having returned to Cairo a week later, he was received by al-Nasir.[19] The sultan would sometimes consult Ibn Taymiyya on religious affairs and policies during the rest of his three-year stay in Cairo.[42][19] During this time he continued to teach and wrote his famous book Al-Kitab al-Siyasa al-shar'iyya (Treatise on the Government of the Religious Law), a book noted for its account of the role of religion in politics.[19][91][92]

Return to Damascus and later years

He spent his last fifteen years in Damascus. Aged 50, Ibn Taymiyya returned to Damascus via Jerusalem on February 28, 1313.[19] Damascus was now under the governorship of Tankiz. There, Ibn Taymiyya continued his teaching role as professor of Hanbali fiqh. This is when he taught his most famous student, Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya, who went on to become a noted scholar in Islamic history.[19] Ibn Qayyim was to share in Ibn Taymiyya's renewed persecution.

Three years after his arrival in the city, Ibn Taymiyya became involved in efforts to deal with the increasing Shia influence amongst Sunni Muslims.[19] An agreement had been made in 1316 between the amir of Mecca and the Ilkhanid ruler Öljaitü, brother of Ghazan Khan, to allow a favourable policy towards Shi'ism in the city.[19] Around the same time the Shia theologian Al-Hilli, who had played a crucial role in the Mongol ruler's decision to make Shi'ism the state religion of Persia,[93][94] wrote the book Minhaj al-Karamah (The Way of Charisma'),[42] which dealt with the Shia doctrine of the Imamate and also served as a refutation of the Sunni doctrine of the caliphate.[95] In response, Ibn Taymiyya wrote his famous book, Minhaj as-Sunnah an-Nabawiyyah, as a refutation of Al-Hilli's work.[96]

his fatwa on divorce and imprisonment

In 1318, Ibn Taymiyya wrote a treatise that would curtail the ease with which a Muslim man could divorce his wife. Ibn Taymiyya's fatwa on divorce was not accepted by the majority of scholars of the time and this continued into the Ottoman era.[97] However, almost every modern Muslim nation-state has come to adopt Ibn Taymiyya's position on this issue of divorce.[97] At the time he issued the fatwa, Ibn Taymiyya revived an edict by the sultan not to issue fatwas on this issue but he continued to do so, saying, "I cannot conceal my knowledge".[19][98] As in previous instances, he stated that his fatwa was based on the Qur'an and hadith. His view on the issue was at odds with the Hanbali position.[19] This proved controversial among the people in Damascus as well as the Islamic scholars who opposed him on the issue.[99]

According to the scholars of the time, an oath of divorce counted as a full divorce and they were also of the view that three oaths of divorce taken under one occasion counted as three separate divorces.[99] The significance of this was, that a man who divorces the same partner three times is no longer allowed to remarry that person until and if that person marries and divorces another person.[99] Only then could the man, who took the oath, remarry his previous wife.[99] Ibn Taymiyya accepted this but rejected the validity of three oaths taken under one sitting to count as three separate divorces as long as the intention was not to divorce.[99] Moreover, Ibn Taymiyya was of the view that a single oath of divorce uttered but not intended, also does not count as an actual divorce.[19] He stated that since this is an oath much like an oath taken in the name of God, a person must expiate for an unintentional oath in a similar manner.[99]

Due to his views and also by not abiding to the sultan's letter two years before forbidding him from issuing a fatwa on the issue, three council hearings were held, in as many years (1318, 1319 and 1320), to deal with this matter.[19] The hearing were overseen by the Viceroy of Syria, Tankiz.[19] This resulted in Ibn Taymiyya being imprisoned on August 26, 1320, in the Citadel of Damascus.[19] He was released about five months and 18 days later,[98] on February 9, 1321, by order of the Sultan Al-Nasir.[19] Ibn Taymiyya was reinstated as teacher of Hanbali law and he resumed teaching.[98]

His risāla on visits to tombs and his final imprisonment

In 1310, Ibn Taymiyya had written a risāla (treatise) called Ziyārat al-Qubūr[19] or according to another source, Shadd al-rihal.[98] It dealt with the validity and permissibility of making a journey to visit the tombs of prophets and saints.[98] It is reported that in the book "he condemned the cult of saints"[19] and declared that traveling with the sole purpose of visiting Muhammad's grave was a blameworthy religious innovation.[100] For this, Ibn Taymiyya, was imprisoned in the Citadel of Damascus sixteen years later on July 18, 1326, aged 63, along with his student Ibn Qayyim.[98] The sultan also prohibited him from issuing any further fatwas.[19][98] Hanbali scholar Ahmad ibn Umar al-Maqdisi accused Ibn Taymiyah of apostasy over the treatise.[101]

His life in prison

Ibn Taymiyya referred to his imprisonment as "a divine blessing".[42] During his incarceration, he wrote that, "when a scholar forsakes what he knows of the Book of God and of the sunnah of His messenger and follows the ruling of a ruler which contravenes a ruling of God and his messenger, he is a renegade, an unbeliever who deserves to be punished in this world and in the hereafter."[42]

During his imprisonment, he encountered opposition from the Maliki and Shafii Chief Justices of Damascus, Taḳī al-Dīn al-Ikhnāʾī.[19] He remained in prison for over two years and ignored the sultan's prohibition, by continuing to deliver fatwas.[19] During his incarceration Ibn Taymiyya wrote three works which are extant; Kitāb Maʿārif al-wuṣūl, Rafʿ al-malām, and Kitāb al-Radd ʿala 'l-Ikhnāʾī (The response to al-Ikhnāʾī).[19] The last book was an attack on Taḳī al-Dīn al-Ikhnāʾī and explained his views on saints (wali).[19]

When the Mongols invaded Syria in 1300, he was among those who called for a Jihad against them and he ruled that even though they had recently converted to Islam, they should be considered unbelievers. He went to Egypt in order to acquire support for his cause and while he was there, he got embroiled in religious-political disputes. Ibn Taymiyya's enemies accused him of advocating anthropomorphism, a view that was objectionable to the teachings of the Ash'ari school of Islamic theology, and in 1306, he was imprisoned for more than a year. Upon his release, he condemned popular Sufi practices and he also condemned the influence of Ibn Arabi (d. 1240), causing him to earn the enmity of leading Sufi shaykhs in Egypt and causing him to serve another prison sentence. In 1310, he was released by the Egyptian Sultan.

In 1313, the Sultan allowed Ibn Taymiyya to return to Damascus, where he worked as a teacher and a jurist. He had supporters among the powerful, but his outspokenness and his nonconformity to traditional Sunni doctrines and his denunciation of Sufi ideals and practices continued to draw the wrath of the religious and political authorities in Syria and Egypt. He was arrested and released several more times, but while he was in prison, he was allowed to write Fatwas (advisory opinions on matters of law) in defense of his beliefs. Despite the controversy that surrounded him, Ibn Taymiyya's influence grew and it spread from Hanbali circles to members of other Sunni legal schools and Sufi groups. Among his foremost students were Ibn Kathir (d. 1373), a leading medieval historian and a Quran commentator, and Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziya (d. 1350), a prominent Hanbali jurist and a theologian who helped spread his teacher's influence after his teacher's death in 1328. Ibn Taymiyya died while he was a prisoner in the citadel of Damascus and he was buried in the city's Sufi cemetery.[102]

Death

He fell ill in early September 1328 and died at the age of 65, on September 26 of that year, whilst in prison at the Citadel of Damascus.[19] Once this news reached the public, there was a strong show of support for him from the people.[103] After the authorities had given permission, it is reported that thousands of people came to show their respects.[103] They gathered in the Citadel and lined the streets up to the Umayyad Mosque.[103] The funeral prayer was held in the citadel by scholar Muhammad Tammam, and a second was held in the mosque.[103] A third and final funeral prayer was held by Ibn Taymiyya's brother, Zain al-Din.[103] He was buried in Damascus, in Maqbara Sufiyya ("the cemetery of the Sufis"). His brother Sharafuddin had been buried in that cemetery before him.[104][105][106]

Oliver Leaman says that being deprived of the means of writing led to Ibn Taymiyya's death.[56] It is reported that two hundred thousand men and fifteen to sixteen thousand women attended his funeral prayer.[60][107] Ibn Kathir says that in the history of Islam, only the funeral of Ahmad ibn Hanbal received a larger attendance.[60] This is also mentioned by Ibn `Abd al-Hadi.[60] Caterina Bori says that, "In the Islamic tradition, wider popular attendance at funerals was a mark of public reverence, a demonstration of the deceased's rectitude, and a sign of divine approbation."[60]

Ibn Taymiyya is said to have "spent a lifetime objecting to tomb veneration, only to cast a more powerful posthumous spell than any of his Sufi contemporaries."[108] On his death, his personal effects were in such demand "that bidders for his lice-killing camphor necklace pushed its price up to 150 dirhams, and his skullcap fetched a full 500."[108][109] A few mourners sought and succeeded in "drinking the water used for bathing his corpse."[108][109] His tomb received "pilgrims and sightseers" for 600 years.[108] His resting place is now "in the parking lot of a maternity ward", though as of 2009 its headstone was broken, according to author Sadakat Kadri.[110][111]

Students

Several of Ibn Taymiyya's students became scholars in their own right.[19] His students came from different backgrounds and belonged to various different schools (madhabs).[112] His most famous students were Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya and Ibn Kathir.[113] His other students include:[19][56][112][114]

- Al-Dhahabi

- Al-Mizzi

- Ibn Abd al-Hadi

- Ibn Muflih

- ʿImad al-Din Aḥmad al-Wasiti

- Najm al-Din al-Tufi

- Al Baʿlabakki

- Al Bazzar

- Ibn Qadi al-Jabal

- Ibn Fadlillah al-Amri

- Muhammad Ibn al-Manj

- Ibn Abdus-Salam al-Batti

- Ibn al-Wardi

- Umar al-Harrani

Legacy

In the 21st century, Ibn Taymiyya is one of the most cited medieval authors and his treatises are regarded to be of central intellectual importance by several Islamic revivalist movements. Ibn Taymiyya's disciples, consisting of both Hanbalis and non-Hanbalis, were attracted to his advocacy of ijtihad outside the established boundaries of the madhabs and shared his taste for activism and religious reform. Some of his unorthodox legal views in the field of Fiqh were also regarded as a challenge by mainstream Fuqaha.[115] Many scholars have argued that Ibn Taymiyya did not enjoy popularity among the intelligentsia of his day.[116] Yossef Rapoport and Shahab Ahmed assert that he was a minority figure in his own times and the centuries that followed.[21] Caterina Bori goes further, arguing that despite popularity Ibn Taymiyya may have enjoyed among the masses, he appears to have been not merely unpopular among the scholars of his day, but somewhat of an embarrassment.[117] Khalid El-Rouayheb notes similarly that Ibn Taymiyya had "very little influence on mainstream Sunni Islam until the nineteenth century"[118] and that he was "a little-read scholar with problematic and controversial views."[119] He also comments "the idea that Ibn Taymiyya had an immediate and significant impact on the course of Sunni Islamic religious history simply does not cohere with the evidence that we have from the five centuries that elapsed between his death and the rise of Sunni revivalism in the modern period."[120] It was only since the late nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries that the scholarly influence of Ibn Taymiyya has come to acquire an unprecedented prominence in Muslim societies, due to the efforts of Islamic revivalists like Rashid Rida.[121] On the other hand, Prof. Al-Matroudi of SOAS university says that Ibn Taymiyya, "was perhaps the most eminent and influential Hanbali jurist of the Middle Ages and one of the most prolific among them. He was also a renowned scholar of Islam whose influence was felt not only during his lifetime but extended through the centuries until the present day."[38] Ibn Taymiyya's followers often deemed him as Sheikh ul-Islam, an honorific title with which he is sometimes still termed today.[122][123][124]

In the pre-modern era, Ibn Taymiyya was considered a controversial figure within Sunni Islam and had a number of critics during his life and in the centuries thereafter.[119] The Shafi'i scholar Ibn Hajar al-Haytami stated that,

Make sure you do not listen to what is in the books of Ibn Taymiyya and his student Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya and other such people who have taken their own whim as their God, and who have been led astray by God, and whose hearts and ears have been sealed, and whose eyes have been covered by Him... May God forsake the one who follows them, and purify the earth of their likes.[125]

He also stated that,

Ibn Taymiyya is a servant whom God has forsaken, led astray, made blind and deaf, and degraded. Such is the explicit verdict of the leading scholars who have exposed the rottenness of his ways and the errors of his statements.[126]

Taqi al-Din al-Hisni condemned Ibn Taymiyya in even stronger terms by referring to him as the "heretic from Harran"[126] and similarly, Munawi considered Ibn Taymiyya to be an innovator though not an unbeliever.[127] Taqi al-Din al-Subki criticised Ibn Taymiyya for "contradicting the consensus of the Muslims by his anthropomorphism, by his claims that accidents exist in God, by suggesting that God was speaking in time, and by his belief in the eternity of the world."[128] Ibn Battūta (d. 770/1369) famously wrote a work questioning Ibn Taymiyya's mental state.[129] The possibility of psychological abnormalities not with-standing, Ibn Taymiyya's personality, by multiple accounts, was fiery and oftentimes unpredictable.[130][131] The historian Al-Maqrizi said, regarding the rift between the Sunni Ash'ari's and Ibn Taymiyya, "People are divided into two factions over the question of Ibn Taymiyya; for until the present, the latter has retained admirers and disciples in Syria and Egypt."[19] Both his supporters and rivals grew to respect Ibn Taymiyya because he was uncompromising in his views.[44] Dhahabi's views towards Ibn Taymiyya were ambivalent.[132][133] His praise of Ibn Taymiyya is invariably qualified with criticism and misgivings[132] and he considered him to be both a "brilliant Shaykh"[38][62] and also "cocky" and "impetuous".[132][134] The Hanafi-Maturidi scholar 'Ala' al-Din al-Bukhari said that anyone that gives Ibn Taymiyya the title Shaykh al-Islām is a disbeliever.[135][136] As a reaction, his contemporary Nasir ad-Din ad-Dimashqi wrote a refutation in which he quoted the 85 greatest scholars, from Ibn Taymiyya's till his time, who called Ibn Taymiyya with the title Shaykh al-Islam.

Despite the prevalent condemnations of Ibn Taymiyya outside Hanbali school during the pre-modern period, many prominent non-Hanbali scholars such as Ibrahim al-Kurrani (d.1690), Shāh Walī Allāh al-Dihlawi (d. 1762), Mehmet Birgiwi (d. 1573), Ibn al-Amīr Al-San'ani (d. 1768), Muḥammad al-Shawkānī (d. 1834), etc. would come to the defense of Ibn Taymiyya and advocate his ideas during this era.[137] In the 18th century, influential South Asian Islamic scholar and revivalist Shah Waliullah Dehlawi would become the most prominent advocate of the doctrines of Ibn Taymiyya, and profoundly transformed the religious thought in South Asia. His seminary, Madrasah-i-Rahimya, became a hub of intellectual life in the country, and the ideas developed there quickly spread to wider academic circles.[138] Making a powerful defense of Ibn Taymiyya and his doctrines, Shah Waliullah wrote:

Our assessment of Ibn Taimiyya after full investigation is that he was a scholar of the 'Book of God' and had full command over its etymological and juristic implications. He remembered by heart the traditions of the prophet and accounts of elders (salaf)... He excelled in intelligence and brilliance. He argued in defence of Ahl al-Sunnah with great eloquence and force. No innovation or irreligious act is reported about him... there is not a single matter on which he is without his defence based on the Qur'an and the Sunnah. So it is difficult to find a man in the whole world who possesses the qualities of Ibn Taimiyya. No one can come anywhere near him in the force of his speech and writing. People who harassed him [and got him thrown in prison] did not possess even one-tenth of his scholarly excellence...[138]

The reputation and stature of Ibn Taymiyya amongst non-Ḥanbalī Sunni scholars would significantly improve between the eighteenth and twentieth centuries. From a little-read scholar considered controversial by many, he would become one of the most popular scholarly figures in the Sunni religious tradition. The nineteenth-century Iraqi scholar Khayr al-Dīn al-Ālūsī (d. 1899) wrote an influential treatise titled Jalā’ al-‘aynayn fi muḥākamat al-Aḥmadayn in defense of Ibn Taymiyya. The treatise would make great impact on major scholars of the Salafiyya movement in Syria and Egypt, such as Jamāl al-Dīn al-Qāsimī (d. 1914) and Muḥammad Rashīd Riḍā (d. 1935). Praising Ibn Taymiyya as a central and heroic Islamic figure of the classical era, Rashid Rida wrote:

...after the power of the Ash‘aris reigned supreme in the Middle Ages (al-qurūn al-wusṭā) and the ahl al-ḥadīth and the followers of the salaf were weakened, there appeared in the eighth century [AH, fourteenth century AD] the great mujaddid, Shaykh al-Islam Aḥmad Taqī al-Dīn Ibn Taymiyya, whose like has not been seen in mastery of both the traditional and rational sciences and in the power of argument. Egypt and India have revived his books and the books of his student Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya, after a time when they were only available in Najd. Now, they have spread to both east and west, and will become the main support of the Muslims of the earth.[139]

Ibn Taymiyya's works served as an inspiration for later Muslim scholars and historical figures, who have been regarded as his admirers or disciples.[19] In the contemporary world, he may be considered at the root of Wahhabism, the Senussi order and other later reformist movements.[10][140] Ibn Taymiyya has been noted to have influenced Rashid Rida, Abul A`la Maududi, Sayyid Qutb, Hassan al-Banna, Abdullah Azzam, and Osama bin Laden.[39][59][141][142][143] The terrorist organization Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant used a fatwa of Ibn Taymiyya to justify the burning alive of Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh.[144] After the Iranian revolution, conservative Sunni ulema robustly championed Ibn Taymiyya's anti-Shia polemics across the Islamic World since the 1980s; and vast majority of Sunni intellectual circles adopted Ibn Taymiyya's rhetoric against Shi'ism.[145]

Influences

Ibn Taymiyya was taught by scholars who were renowned in their time.[146] However, there is no evidence that any of the contemporary scholars influenced him.[146]

A strong influence on Ibn Taymiyya was the founder of the Hanbali school of Islamic jurisprudence, Ahmad ibn Hanbal.[146] Ibn Taymiyya was trained in this school and he had studied Ibn Hanbal's Musnad in great detail, having studied it over multiple times.[147] Though he spent much of his life following this school, in the end he renounced taqlid (blind following).[58]

His work was most influenced by the sayings and actions of the Salaf (first 3 generation of Muslims) and this showed in his work where he would give preference to the Salaf over his contemporaries.[146] The modern Salafi movement derives its name from this school of thought.[146]

Views

God's attributes

Ibn Taymiyya said that God should be described as he has described himself in the Qur'an and the way Muhammad has described God in the Hadith.[19][56] He rejected the Ta'tili's who denied these attributes, those who compare God with the creation (Tashbih) and those who engage in esoteric interpretations (ta'wil) of the Qur'an or use symbolic exegesis.[19] Ibn Taymiyya said that those attributes which we know about from the two above mentioned sources, should be ascribed to God.[19] Anything regarding God's attributes which people have no knowledge of, should be approached in a manner, according to Ibn Taymiyya, where the mystery of the unknown is left to God (called tafwid) and the Muslims submit themselves to the word of God and the prophet (called taslim).[19] Henri Laoust says that through this framework, this doctrine, "provides authority for the widest possible scope in personal internationalization of religion."[19]

In 1299, Ibn Taymiyya wrote the book Al-Aqida al-hamawiyya al-kubra, which dealt with, among other topics, theology and creed. When he was accused of anthropomorphism, a private meeting was held between scholars in the house of Al-Din `Umar al-Kazwini who was a Shafii judge.[19][148] After careful study of this book, he was cleared of those charges.[19] Ibn Taymiyya also wrote another book dealing with the attributes of God called, Al-Aqidah Al-Waasitiyyah. He faced considerable hostility towards these views from the Ash'ari's of whom the most notable were, Taqi al-Din al-Subki and his son Taj al-Din al-Subki who were influential Islamic jurists and also chief judge of Damascus in their respective times.[19]

Ibn Taymiyya's highly intellectual discourse at explaining "The Wise Purpose of God, Human Agency, and the Problems of Evil & Justice" using God's Attributes as a means has been illustrated by Dr. Jon Hoover in his work Ibn Taymiyya's Theodicy of Perpetual Optimism.[149]</ref> Ibn Taymiyya regarded Tawhid al-Asma wa Sifat (‘monotheism of God's Names and Attributes’) as the third aspect of Tawhid and as part of Tawhid al-Uluhiyya (monotheism of Worship). According to Ibn Taymiyya, God must be worshipped by His Own Names and Attributes – by which He described himself in the Qur’ān and Hadith – and to do otherwise would be to commit shirk (polytheism) by associating God with improper ideas.[150]

Duration of Hellfire

Ibn Taymiyya held the belief that Hell was not eternal even for unbelievers.[151] According to Ibn Taymiyya, Hell is therapeutic and reformative, and God's wise purpose in chastising unbelievers is to make them fit to leave the Fire.[151] This view contradicted the mainstream Sunni doctrine of eternal hell-fire for unbelievers.[152] Ibn Taymiyya was criticised for holding this view by the chief Shafi scholar Taqi al-Din al-Subki who presented a large body of Qur'anic evidence to argue that unbelievers will abide in hell-fire eternally.[153] Ibn Taymiyya was partially supported in his view by the Zaydi Shi'ite Ibn al-Wazir.[151]

Sources of Sharīʿa

Of the four fundamental sources of the sharia accepted by thirteenth century Sunni jurists—

- Qur'an,

- sunnah,

- consensus of jurists (ijma), and

- qiyas (analogical reasoning),

—Ibn Taymiyya opposed the use of consensus of jurists, replacing it with the consensus of the "companions" (sahaba).[40][154]

Like all Islamic jurists Ibn Taymiyya believed in a hierarchy sources for the Sharia. Most important was the Quran, and the sunnah or any other source could not abrogate a verse of the Qur'an.[155] (For him, an abrogation of a verse, known in Arabic as Naskh, was only possible through another verse in the Qur'an.[155]) Next was sunnah which other sources (besides the Quran) must not contradict.

Consensus (ijmaʾ)

Concerning Consensus (ijma), he believed that consensus of any Muslims other than that of the companions of Muhammad could not be "realistically verifiable" and so was speculative,[40] and thus not a legitimate source of Islamic law (except in certain circumstances).[40] The consensus (ijma) used must be that of the companions found in their reported sayings or actions.[155] According one supporter, Serajul Haque, his rejection of the consensus of other scholars was justified, on the basis of the instructions given to the jurist Shuraih ibn al-Hârith from the Caliph Umar, one of the companions of Muhammad; to make decisions by first referring to the Qur'an, and if that is not possible, then to the sayings of Muhammad and finally to refer to the agreement of the companions like himself.[155]

An example of Ibn Taymiyya use of his interpretation was in defense of the (temporary) closing of all Christian churches in 1299 in the Mamluk Sultanate during hostility against crusader states. The closing was in violation of a 600-year-old covenant with Christian dhimmis known as the Pact of Umar. But as Ibn Taymiyya pointed out, while venerable, the pact was written 60 years or so after the time of the companions and so had no legal effect.[154]

Analogy (qiyās)

Ibn Taymiyya considered the use of analogy (qiyas) based on literal meaning of scripture as a valid source for deriving legal rulings.[40][156] Analogy is the primary instrument of legal rationalism in Islam.[62] He acknowledged its use as one of the four fundamental principles of Islamic jurisprudence.[157] Ibn Taymiyya argued against the certainty of syllogistic arguments and in favour of analogy. He argues that concepts founded on induction are themselves not certain but only probable, and thus a syllogism based on such concepts is no more certain than an argument based on analogy. He further claimed that induction itself depends on a process of analogy. His model of analogical reasoning was based on that of juridical arguments.[158][159] Works by American computer scientists like John F. Sowa have, for example, have used Ibn Taymiyya's model of analogy.[159] He attached caveats however to the use of analogy because he considered the use of reason to be secondary to the use of revelation.[40] Ibn Taymiyya's view was that analogy should be used under the framework of revelation, as a supporting source.[40]

There were some jurists who thought rulings derived through analogy could contradict a ruling derived from the Qur'an and the authentic hadith.[40] However, Ibn Taymiyya disagreed because he thought a contradiction between the definitive canonical texts of Islam, and definitive reason was impossible[40] and that this was also the understanding of the salaf.[160] Racha el-Omari says that on an epistemological level, Ibn Taymiyya considered the Salaf to be better than any other later scholars in understanding the agreement between revelation and reason.[160] One example for this is the use of analogy in the Islamic legal principle of maslaha (public good) about which Ibn Taymiyya believed, if there were to be any contradiction to revelation then it is due to a misunderstanding or misapplication of the concept of utility.[62][161] He said that to assess the utility of something, the criteria for benefit and harm should come from the Qur'an and sunnah, a criterion which he also applied to the establishment of a correct analogy.[62][161]

An example of Ibn Taymiyya's use of analogy was in a fatwa forbidding the use of hashish on the grounds that it was analogous to wine, and users should be given 80 lashes in punishment. "Anyone who disagreed was an apostate, he added, whose corpse ought not to be washed or given a decent burial."[154]

Prayer (Duʿāʾ)

Ibn Taymiyya issued a fatwa deeming it acceptable to perform dua in languages other than Arabic:

It is permissible to make du'aa' in Arabic and in languages other than Arabic. Allaah knows the intention of the supplicant and what he wants, no matter what language he speaks, because He hears all the voices in all different languages, asking for all kinds of needs.[162]

This view was also shared by an earlier theologian and jurist, Abu Hanifa.[163] [164]

Interest (Rįbā)

Ibn Taymiyya held the view that the lender of a loan is allowed to recover the original, inflation adjusted value. Ahmad ibn Hanbal, the eponym of the Hanbali madh'hab believed that only the practice of 'pay or increase' – which extended delay to debtors in exchange for rise in the principal – as the only form of riba (i.e., Riba al-Jahiliyya) that was definitively and conclusively prohibited in Shari'ah (Islamic law). Ibn Qudama, another notable Hanbali jurist that preceded Ibn Taymiyya; opined that debtors who took loans involving unweighable, immeasurable objects should give back the original value to the creditors. This provided a basis for the argument that a creditor is allowed to "recover a sum equivalent to the amount by which the original principal lent has depreciated in real terms during the period of the loan". Building on Ibn Qudama's specific argument on unweighable objects, Ibn Taymiyya would argue for a more general view. He stipulated that the lender should be able to recover the original, inflation-adjusted value; reasoning that lenders unable to recover for losses from inflation would be far less inclined to grant future loans. In Ibn Taymiyya's view, such a lender was not involved in riba, since he has not made any actual profit out of the transaction.[165] Ibn Taymiyya held that the term riba also included all types of interest resulting from late payment (riba al-nasi'ah) or due to unequal exchange of the same commodity (riba al-fadl). Riba thus covers some cases of barter which involve exchanges unequal by way of quantity or time of delivery.[166]

Reason (ʿAql)

Issues surrounding the use of reason ('Aql) and rational came about in relation to the attributes of God for which he faced much resistance.[62] At the time, Ashari and Maturidi theologians thought the literal attributes of God as stated in the Qur'an were contradictory to reason so sought to interpret them metaphorically.[62] Ibn Taymiyya believed that reason itself validated the entire Qur'an as being reliable and in light of that he argued, if some part of the scripture was to be rejected then this would render the use of reason as an unacceptable avenue through which to seek knowledge.[62] He thought that the most perfect rational method and use of reason was contained within the Qur'an and sunnah and that the theologians of his time had used rational and reason in a flawed manner.[62]

Condemning formal logic as "laughable and boring", Ibn Taymiyya writes:[168]

"The validity of the form of the syllogism is irrefutable, but it does not lead to knowledge of things in the external world... Even if the syllogism yields certitude, it cannot alone lead to certainty about things existing in the external world... It must be maintained that the numerous figures they have elaborated and the conditions they have stipulated for their validity are useless, tedious, and prolix. These resemble the flesh of a camel found of the summit of a mountain, the mountain is not easy to climb, nor the flesh plump enough to make it worth the hauling"[168][169]

Criticism of the grammarians

Ibn Taymiyya had mastered the grammar of Arabic and one of the books which he studied was the book of Arabic grammar called Al-Kitab, by Sibawayh.[170] In later life he met the Quranic exegete and grammarian Abu Hayyan al-Gharnati to whom he expressed that, "Sibawayh was not the prophet of syntax, nor was he infallible. He committed eighty mistakes in his book which are not intelligible to you."[170] Ibn Taymiyya is thought to have severely criticized Sibawayh but the actual substance of those criticisms is not known because the book within which he wrote the criticisms, al-Bahr, has been lost.[170] He stated that when there is an explanation of an Ayah of the Qur'an or a Hadith, from the prophet himself, the use of philology or a grammatical explanation becomes obsolete.[171] He also said one should refer only to the understanding of the Salaf (first three generations of Muslims) when interpreting a word within the scriptural sources.[62] However he did not discount the contributions of the grammarians completely.[172] Ibn Taymiyya stated that the Arabic nouns within the scriptural sources have been divided by the fuqaha (Islamic jurists) into three categories; those that are defined by the shari'a, those defined by philology (lugha) and finally those that are defined by social custom (`urf).[171] For him each of these categories of nouns had to be used in their own appropriate manner.[173]

Maddhabs

Ibn Taymiyya censured the scholars for blindly conforming (Taqlid) to the precedence of early jurists without any resort to the Qur'an and Sunnah. He contended that although juridical precedence has its place, blindly giving it authority without contextualization, sensitivity to societal changes, and evaluative mindset in light of the Qur'an and Sunnah can lead to ignorance and stagnancy in Islamic Law. Ibn Taymiyya likened the extremism of Taqlid (blind conformity to juridical precedence or school of thought) to the practice of Jews and Christians who took their rabbis and ecclesiastics as gods besides God. In arguing against taqlid, he stated that the Salaf, who to better understand and live according to the commands of God, had to make ijtihad using the scriptural sources.[59] The same approach, in his view, was needed in modern times.[59] Ibn Taymiyya considered his attachment to the Ḥanbalī school as a scholarly choice based on his Ijtihad (independent legal reasoning), rather than on imitation (taqlīd). Based on the principles and legal methodology of Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Ibn Taymiyya issued fatwas as per scriptural evidence, rather than juristic opinion (ra'y). He insisted that the dominant opinion of Hanbali school transmitted through Ahmad's reports is not necessarily the correct view in sharia and often critiqued the rulings of prominent Hanbali Fuqaha.[174]

Ibn Taymiyya believed that the best role models for Islamic life were the first three generations of Islam (Salaf); which constitute Muhammad's companions, referred to in Arabic as Sahaba (first generation), followed by the generation of Muslims born after the death of Muhammad known as the Tabi'un (second generation) which is then followed lastly by the next generation after the Tabi'un known as Tabi' al-Tabi'in (third generation). Ibn Taymiyya gave precedence to the ideas of the Sahaba and early generations, over the founders of the Islamic schools of jurisprudence.[19] For Ibn Taymiyya it was the Qur'an, the sayings and practices of Muhammad and the ideas of the early generations of Muslims that constituted the best understanding of Islam. Any deviation from their practice was viewed as bid'ah, or innovation, and to be forbidden. He also praised and wrote a commentary on some speeches of Abdul-Qadir Gilani.[175]

Ibn Taymiyya asserted that every individual is permitted to employ Ijtihad partially as per his potential; despite the fact that scholars, jurists, etc. had superior knowledge and understanding of the law than the laity. Ibn Taymiyya writes:

"Ijtihād is not one whole that cannot be subject to division and partition. A man could be a mujtahid in one discipline or one field (bāb) or an individual legal question, without being a mujtahid in all other disciplines, or books, or questions. Everyone can practice ijtihād according to his abilities. When one observes a legal question that has been subject to a dispute among the scholars, and then one finds revealed texts in support of one of the opinions, with no known counter-evidence (mu‘āriḍ), then there are two choices.... The second option is to follow the opinion that he, in his own judgment, finds preponderant by the indicants from the revealed texts. He is then in agreement with the founder of a different school, yet for him the revealed texts remain uncorrupted, as they are not contradicted by his actions. And this is the right thing to do."

Conscious of the limitations of the human mind, Ibn Taymiyya does not reject taqlid completely; since most people are not capable to be a legal expert who can derive law from its sources. Ibn Taymiyya asserted throughout his legal writings that "God does not burden men with more than they are capable of undertaking." Even Fuqaha are allowed to attach themselves to a mad'hab (law school) so long as they prefer the evidences. However, Ibn Taymiyya denounced all manifestations of Madh'hab fanaticism and was careful to emphasize that school affiliations are not obligatory. He argued that opinions of any jurist, including the school founders were not proofs, and decried the prevalent legal approach; wherein the Fuqaha confined themselves to the opinions within their legal school without seeking the Scriptures. Consequently, Ibn Taymiyya stripped Sunni legal conformism of any definitive, static religious authority. In his treatise "Removal of Blame from the Great Imams", Ibn Taymiyya explained the reasons for difference of opinions between jurists of various schools of law and justified the necessity for tolerance between the scholars of the madh'habs and their eponyms; reminding that every Mujtahid is rewarded twice if his Ijtihad is correct and rewarded once if his Ijtihad is faulty. Hence, a jurist acting in good faith should not incur blame for reaching the wrong conclusions. Thus, the Islamic scholarly system championed by Ibn Taymiyya subjected all Islamic jurists just to the authority of the revealed texts and not to the views of madh'habs, or jurists or any similar affiliations. Thus, Ibn Taymiyya envisioned a world in which individuals stand before the Divine revelation, with the intellectual freedom to discern the universal rulings of God's law to the best of their abilities.[177][176]

Ikhtilaf

Even though jurists may err in their fatwas; Ibn Taymiyya asserted that they should never be deterred from pursuing ijtihād. His outlook which was incompatible with a stagnated juristic system; propelled Ibn Taymiyya to advance legal pluralism; that defended the freedom of multiple juristic interpretations. According to Ibn Taymiyya, on legal issues which are subject to Ikhtilaf (scholarly disagreement); every Muslim is allowed to formulate and express his own opinion:

"In these general matters [i.e., not a specific trial case] no judge, whoever he may be—even if he was one of the Companions—can impose his view on another person who does not share his opinion... In these matters, judgment is reserved for God and His messenger.. But, as long as the judgment of God is concealed, each of them is allowed to hold his opinion—the one saying ‘this is my opinion’ while the other says ‘this is my opinion.’ They are not allowed to prevent each other from expressing his opinion, except through the vehicles of knowledge, proof (ḥujja) and evidence (bayān), so that each speaks on the basis of the knowledge that he has."

Islamic law and policy

Ibn Taymiyya believed that Islamic policy and management was based on Quran 4:58,[179] and that the goal of al-siyasa (politics, the political) should be to protect al-din (religion) and to manage al-dunya (worldly life and affairs). Religion and the State should be inextricably linked, in his view,[19] as the state was indispensable in providing justice to the people, enforcing Islamic law by enjoining good and forbidding evil, unifying the people and preparing a society conducive to the worship of God.[19] He believed that "enjoining good and forbidding wrong" was the duty of every state functionary with charge over other Muslims, from the caliph to "the schoolmaster in charge of assessing children's handwriting exercises."[180][181] Apart from his theological discourse that centered around Divine Attributes and God's Nature, Ibn Taymiyya also expanded Tawhid (Islamic montheism) doctrine to stress the significance of socio-political affairs. Ibn Taymiyya believed that monotheism in Islam affirmed God as the "sole creator, ruler, and judge of the world" and hence; Muslims are duty-bound to submit to Divine Commandments as revealed through Sharia (Islamic law) through both private and collective enforcement of religious rituals and morality.[182]

Ibn Taymiyya supported giving broad powers to the state. In Al-siyasa al-Sharʿiyah, he focused on duties of individuals and punishments rather than rules and procedural limits of authorities.[181] Suspected highway robbers who would not reveal their accomplices or the location of their loot, for example should be held in detention and lashed for indefinite periods.[181] He also allowed the lashing of imprisoned debtors, and "trials of suspicion" (daʿsawī al-tuḥam) where defendants could be convicted without witnesses or documentary proof.[183]

Henri Laoust said that Ibn Taymiyya never propagated the idea of a single caliphate but believed the Muslim ummah or community would form into a confederation of states.[19] Laoust further stated that Ibn Taymiyya called for obedience only to God, and the Islamic prophet Muhammad, and he did not put a limit on the number of leaders a Muslim community could have.[19] However Mona Hassan, in her recent study of the political thoughts of Ibn Taymiyya, questions this and says Laoust has wrongly claimed that Ibn Taymiyya thought of the caliphate as a redundant idea.[184] Hassan has shown that Ibn Taymiyya considered the Caliphate that was under the Rashidun Caliphs; Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali, as the moral and legal ideal.[184] The Caliphate in his view could not be ceded "in favour of secular kingship (mulk).[184]

Jihad

Ibn Taymiyya was noted for his emphasis on the importance of jihad and for the "careful and lengthy attention" he gave "to the questions of martyrdom" in jihad, such as benefits and blessings to be had for martyrs in the afterlife.[185] Alongside his disciple Ibn Kathir, Ibn Taymiyya is widely regarded as one of the most influential classical theoreticians of armed Jihad.[186] Ibn Taymiyya believed that martyrdom in Jihad grants eternal rewards and blessings. He wrote that, "It is in jihad that one can live and die in ultimate happiness, both in this world and in the Hereafter. Abandoning it means losing entirely or partially both kinds of happiness."[187]

He defined jihad as:

It comprehends all sorts of worship, whether inward or outward, including love for Allah, being sincere to Him, relying on Him, relinquishing one's soul and property for His sake, being patient and austere, and keeping remembrance of Almighty Allah. It includes what is done by physical power, what is done by the heart, what is done by the tongue through calling to the way of Allah by means of authoritative proofs and providing opinions, and what is done through management, industry, and wealth.[188]

He gave a broad definition of what constituted "aggression" against Muslims and what actions by non-believers made jihad against them permissible. He declared

It is allowed to fight people for (not observing) unambiguous and generally recognized obligations and prohibitions, until they undertake to perform the explicitly prescribed prayers, to pay zakat, to fast during the month of Ramadan, to make the pilgrimage to Mecca and to avoid what is prohibited, such as marrying women in spite of legal impediments, eating impure things, acting unlawfully against the lives and properties of Muslims and the like. It is obligatory to take the initiative in fighting those people, as soon as the prophet's summons with the reasons for which they are fought has reached them. But if they first attack the Muslims then fighting them is even more urgent, as we have mentioned when dealing with the fighting against rebellious and aggressive bandits.[185][189]

In the modern context, his rulings have been used by some Islamist groups to declare jihad against various governments.[190]

On Martyrdom Operations (Inghimas)

Ibn Taymiyya was a major proponent of a form of Martyrdom operations during Jihad known as ''inghimas'' (plunging into the enemy). Although suicide is considered sinful in traditional Islamic law, Ibn Taymiyya distinguished between inghimas and suicide, asserting that the former is Martyrdom. Ibn Taymiyya sanctioned the act of plunging into the armies of non-Muslims even if the Muslim fighter or fighters are certain that they will be killed; as long as it benefited Islam for the purpose of Jihad.[191][192] Ibn Taymiyya argued that inghimas were sanctioned in three battlefield scenarios:

- When a Muslim soldier charges individually into a large army of non-Muslims in such a way that he gets overwhelmed by them

- When a Muslim soldier undertakes a mission to assassinate the commander of disbelievers, even if it is certain that he may get killed

- When a Muslim soldier remains to fight the enemy armies alone, even after retreat and defeat[191][193]

Ibn Taymiyya praised inghimas as a part of the religious command to wage Jihad and attain Shuhada (martyrdom) in battlefield. Furthermore, he asserted that the practice was mainstream during the era of Muhammad and the companions. In support of his stances, Ibn Taymiyya refers to the Qurʾānic story of the People of the Ditch; writing[191][194][195]

"In the story [of the Companions of the Pit] the young boy is ordered to get himself killed to manifest religion's splendor. For this reason the four imams have permitted a Muslim to plunge into the ranks of the unbelievers, even if he thinks they will kill him, on condition that this [act] is in the interest of Muslims."

Apart from Inghimasi, Ibn Taymiyya also issued legal verdicts sanctioning the killing of Muslim civilians who are employed as "human shields" by the enemy armies, a tactic frequently used by the Mongols, but only if the Muslim army had no other choice. In Ibn Taymiyya's view, Muslims killed in such operations are to be honoured as shuhada (martyrs) and such tactics are justifiable since the benefits exceed its detriments.[196][197] In the modern-era, various Jihadist ideologues have exploited Ibn Taymiyya's fatwas for inghimasi operations to justify Suicide Bombings as martyrdom. In retaliation to the Jyllands-Posten Muhammad cartoons controversy, Al-Qaeda conducted the 2008 Danish Embassy suicide bombing in Islamabad, based on Ibn Taymiyya's works. Directly quoting from Ibn Taymiyya's extracts, Islamic State (IS) would launch large-scale inghimasi operations as a novel terror tactic of suicide bombings during its 2014 insurgency across Iraq and Syria.[198][199][200] Scholars like Rebecca Molfoy have disputed this view, asserting that Ibn Taymiyya did not legalise mass-murder of non-combatants, but sanctioned inghimasi only in battlefield, when outnumbered and when it was beneficial to Islam. According to Molfoy, unlike suicide bombings which necessitate taking one's own life, Ibn Taymiyya held that it was possible to come out alive after Inghimasi operations, even while glorifying martyrdom.[201]

Innovation (Bidʿah)

Even though Ibn Taymiyya has been called a theologian,[202] he claimed to reject ʿIlm al-Kalam, known as Islamic theology, as well as some aspects of Sufism and Peripatetic philosophy, as an innovation (Bid'ah).[113] Despite this, Ibn Taymiyya's works contained numerous arguments that openly refer to rational arguments (kalam) for their validity[203] and therefore he is included by some scholars as amongst the Mutakallimin.[204]