Indian Gorkha

Indian Gorkhas, also known as Nepali Indians, are Nepali language-speaking citizens in the Indian Republic. The modern term "Indian Gorkha" is used to differentiate the ethnic Gorkhas from Nepalis.[1]

Gorkha regiment soldiers Men of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Gorkha Rifles (Frontier Force) of the Indian Army operating alongside soldiers from the 82nd Airborne Division of the US Army in 2013 | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2,926,168 (2011 Indian Census) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Sikkim · Darjeeling · Assam · Dehradun | |

| Languages | |

| Nepali · Hindi · Limbu · Gurung · Magar · Tamang | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Burmese Gorkha · Indian people · Nepali people · Sikkimese people |

Indian Gorkhas are citizens of India as per the gazette notification of the Government of India on the issue of citizenship of the Gorkhas from India.[2] The Nepali language is included in the eighth schedule of the Indian Constitution.[3] However, the Indian Gorkhas are faced with a unique identity crisis with regard to their Indian citizenship because of the Indo-Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship (1950) that permits "on a reciprocal basis, the nationals of one country in the territories of the other the same privileges in the matter of residence, ownership of property, participation in trade and commerce, movement and other privileges of a similar nature".

Ethnicities and castes

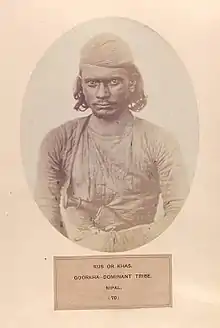

Indian Gorkhas are considered an Indian indigenous ethnic group found in multiple states in northeastern part of the country with a mixture of castes and ethno-tribe clans. The Gorkhali Parbatiya ethnic groups include the Khas-Parbatiyas such as Bahun (hill Brahmins), Chhetri (Khas), Thakuri, Badi, Kami, Damai, Sarki, Gandarbha, Kumal, etc. Other Tibeto-ethnic groups include Tamang, Gurung, Magar, Newar, Bhujel (Khawas), Sherpa and Thami.[4] The Kirati people include Khambu (Rai), Limbu (Subba), Sunuwar (Mukhiya), Yakkha (Dewan), Dhimal, etc. Although each of them has its own language (belonging to the Tibeto-Burman languages or Indo-Aryan languages), the lingua franca among the Gorkhas is the Nepali language with its script in Devnagari. It is one of the official languages of India.

Population

| Census | Nepali speakers | Growth |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 1,419,835 | — |

| 1981 | 1,360,636 | |

| 1991 | 2,076,645 | |

| 2001 | 2,871,749 | |

| 2011 | 2,926,168 |

As per the 2011 Census, a total of 2,926,168 people in India spoke Nepali as their mother tongue.[7] The largest populations can be found in West Bengal – 1,155,375 (+12.97% from 2001 Census), Assam – 596,210 (+5.56%), Sikkim – 382,200 (+12.87%), Uttarakhand – 106,399 (+16.86%), Arunachal Pradesh – 95,317 (+00.42%), Himachal Pradesh – 89,508 (+27.37%), Maharashtra – 75,683 (+19.22%), Manipur – 63,756 (+38.61%), Meghalaya – 54,716 (+4.91%), Nagaland – 43,481 (+27.06%), and Mizoram – 8,994 (+0.51%).[8] Apart from this, there are additional speakers of languages such as Limbu (40,835), Rai (15,644), Sherpa (16,012) and Tamang (20,154). So the combined strength of Nepali and the other four Gorkha languages comes to 3,018,813.[9]

As per the 2001 Census, a total of 2,871,749 people in India spoke Nepali as their mother tongue. The largest populations were in West Bengal – 1,022,725 (+18.87% from 1991 Census), Assam – 564,790 (+30.58%), Sikkim – 338,606 (+32.05%), Uttarakhand – 355,029 (+255.53%), Arunachal Pradesh – 94,919 (+16.93%), Himachal Pradesh – 70,272 (+50.64%), Maharashtra – 63,480 (+59.69%), Meghalaya – 52,155 (+6.04%), Manipur – 45,998 (−1.08%), Nagaland – 34,222 (+6.04%), and Mizoram – 8,948 (+8.50%). As per the 1991 Census, the number of Nepali speakers in India was 2,076,645.

Arunachal Pradesh

As per the 2001 Census, districts with the largest Nepali populations are West Kameng – 13,580 (18.2% of the total population) Lohit – 22,200 (15.77%), and Dibang Valley – 15,452 (26.77%). Tehsils with the largest proportion of Nepalis are Koronu (55.35%), Kibithoo (50.68%), Sunpura (42.28%), Vijoynagar (42.13%), and Roing (32.39%).

As per the 2011 Census, districts with the largest Nepali populations are West Kameng – 14,333 (17.1% of the total population) Lohit – 22,988 (13.77%), and Dibang Valley – 14,271 (22.99%). Tehsils with the largest proportion of Nepalis are Koronu (48.49%), Kibithoo (6.5%), Sunpura (34.47%), Vijoynagar (41.8%), and Roing (26.0%).

Assam

During the 1991 Census, the districts with the largest concentrations were Sonitpur – 91,631 (6.43%), Tinsukia – 76,083 (7.91%), and Karbi Anglong – 37,710 (5.69%).[10]

As per the 2001 Census, districts with the largest ethnic Nepali populations are Sonitpur – 131,261 (7.81% of the total population) Tinsukia – 87,850 (7.64%), and Karbi Anglong – 46,871 (5.76%). Tehsils with the largest proportion of Nepalis are Sadiya (27.51%), Na Duar (16.39%), Helem (15.43%), Margherita (13.10%), and Umrangso (12.37%).

As per the 2011 Census, districts with the largest ethnic Nepali populations are Sonitpur – 135,525 (7.04% of the total population) Tinsukia – 99,812 (7.52%), and Karbi Anglong – 51,496 (5.38%). Tehsils with the largest proportion of Nepalis are Sadiya (26.2%), Na Duar (14.88%), Helem (14.35%), Margherita (13.47%), and Umrangso (12.46%).

Manipur

As per the 2011 census, Tehsils with the largest proportion of Nepali people are Sadar Hills West (33.0%), Saitu-Gamphazol (9.54%), and Lamshang (10.85%). Districts with the largest Nepali population are Senapati – 39,039 (8.15%), Imphal West – 10,391 (2.01%) and Imphal East – 6,903 (1.51%).

This is how the previous censuses counted the number of Nepali speakers in Manipur:

- 1961 Census: 13,571

- 1971 Census: 26,381

- 1981 Census: 37,046

- 1991 Census: 46,500

- 2001 Census: 45,998 (*)

- 2011 Census: 63,756

Meghalaya

Gorkha population is mostly concentrated in the districts of East Khasi Hills (37,000 or 4.48%) and Ribhoi (10,524 or 4.07%). Tehsils with the largest concentration include Myliem (8.18%) and Umling (6.72%).

Among the cities, the highest concentration of Nepali speakers can be found in Shillong Cantonment (29.98%), Shillong (9.83%), Pynthorumkhrah (7.02%), Nongmynsong (26.67%), Madanrting (17.83%), and Nongkseh (14.20%).

This is how the previous censuses counted the number of Nepali speakers in Meghalaya:[11]

- 1961: 32,288

- 1971: 44,445

- 1981: 61,259

- 1991: 49,186

- 2001: 52,155

- 2011: 54,716

Mizoram

As per the 2011 Census, there are a total of 9,035 Gorkhas in Mizoram. Of this, 5,944 are concentrated in Tlangnuam Tehsil of Aizawl district, where they form 1.9% of the population. The Central Gorkha Mandir Committee operates a total of 13 Hindu temples in Mizoram and these are the only Hindu places of worship in the state.[12]

Nagaland

Most of the Nepali speaking population are found in the districts of Dimapur (21,596 or 5.70%) and Kohima (9,812 or 3.66%). Tehsils with the largest concentration are Naginimora (7.48%), Merangmen (6.78%), Niuland (6.48%), Kuhoboto (7.04%), Chümoukedima (7.07%), Dhansiripar (6.09%), Medziphema (9.11%), Namsang (8.81%), Kohima Sadar (6.27%), Sechü-Zubza (5.03%), and Pedi (7.61%).

Sikkim

The state of Sikkim is the only state in India with a majority ethnic Nepali population.[13] The Sikkim census of 2011 found that Sikkim was the least populated state of India. Sikkim's population according to the 2011 Census was 610,577, and has grown by approximately 100,000 since the last census.[14] The Nepali/Gorkhali language is the lingua franca of Sikkim, while Tibetan (Bhutia) and Lepcha are spoken in certain areas.[15][16] As per the 2011 Census, there were a total of 453,819 speakers of various Tibetan languages (Nepali – 382,200, Limbu – 38,733, Sherpa – 13,681, Tamang – 11,734 and Rai – 7,471). Out of this, 20.14% (91,399) were Tibetan Limbu/Tamang, 6.23% (28,275) were Dalit and 73.63% were General category.

According to the census, there are a total of 53,703 Limbu and 37,696 Tamang in Sikkim, of whom a majority speak the Nepali language as their mother tongue. Also, small numbers of Bhotia and Lepcha also speak the Nepali language as their mother tongue. As per the 2011 Census, there were a total of 69,598 Bhotia in Sikkim (including Sherpa, Tamang, Gurung and Tibetan. etc), but only 58,355 were speaking languages such as Sikkimese and Sherpa. Out of the 42,909 Lepcha there were only 38,313 speakers for the Lepcha language.

Uttarakhand

As per the 2011 census, the total number of Nepali language speakers is 106,399, constituting 1.1% of the total population of the state.[17]

West Bengal

As per the 2001 Census, there are a total of 1,034,038 ethnic Gorkhas in West Bengal, of which 1,022,725 are speakers of the Nepali language and 11,313 are speakers of languages such as Tamang and Sherpa. The population in the Darjeeling and Kalimpong districts are 748,023 (46.48% of the total population) and Jalpaiguri – 234,500 (6.99%). Most of the ethnic Nepali population in West Bengal live in the Gorkhaland Territorial Administration region.[18] About 7.56% of the Nepalis were Dalit, belonging to castes such as Kami and Sarki (population of 78,202 in 2001). The two tribes classified as Scheduled Tribe (Limbu and Tamang) constituted 16% of the Nepali population according to the census. The remaining 76% belonged to general category.

As per the 2011 Census, there were a total of 1,161,807 speakers of various Nepalese languages. Out of this 7.24% was Dalit (84,110) and 16.62% (193,050) were tribal Tamang/Limbu. Remaining 76.14% were General category.

Forced displacement

Nepali-speaking people in the states of Northeast India have faced violence and ethnic cleansing. In 1967, more than 8,000 Nepali-speaking people were driven out of Mizoram, while more than 2,000 in Manipur met with the same fate in 1980. Tens of thousands of Nepali-speaking people were banished from Assam (in 1979) and Meghalaya (in 1987) by militant groups.[19]

The biggest displacement occurred in Meghalaya, when the Khasi Students Union (KSU) targeted Nepali speakers living in the eastern part of the state. More than 15,000 Nepali speakers were driven out, while about 10,000 were reduced to living in subhuman life in the refugee camps of Shillong.[20] Gorkha labourers in the coal mines in Jowai were targeted, and as a result of their murders dozens of Gorkha children starved to death in the next few weeks.[21] In 2010, there were riots between Khasis and Gorkhas, which left several Gorkhas dead. One elderly Gorkha man was burnt alive.[22][23]

In 1980s, most of the Gorkha in Nagaland were forced to forfeit their land, and 200 of them were murdered near Merapani in Wokha district.[21]

Politics

The Gorkhaland movement is a campaign to create a separate state of India in the Gorkhaland region of West Bengal for the Nepali speaking Indians. The proposed state includes the hill regions of the Darjeeling district, Kalimpong district and Dooars regions that include Jalpaiguri, Alipurduar and parts of Coochbehar districts. A demand for a separate administrative unit in Darjeeling has existed since 1909, when the Hillmen's Association of Darjeeling submitted a memorandum to Minto-Morley Reforms demanding a separate administrative setup.[24]

Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council

Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council (DGHC) (1988–2012), also once known for a short period of time as Darjeeling Gorkha Autonomous Hill Council was a semi-autonomous body that looked after the administration of the hills of Darjeeling District in the state of West Bengal, India. DGHC had three subdivisions under its authority: Darjeeling, Kalimpong, and Kurseong and some areas of Siliguri subdivision.

Led by Subhash Ghisingh, Gorkhas raised the demand for the creation of a state called Gorkhaland within India to be carved out of the hills of Darjeeling and areas of Dooars and Siliguri terai contiguous to Darjeeling. A violent agitation erupted in the Darjeeling hills from 1986 to 1988 in which 1200 people lost their lives.

The semi-autonomous Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council was the result of the signing of the Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council Agreement between the Central Government of India, the West Bengal Government and the Gorkha National Liberation Front in Kolkata on 22 August 1988.

Gorkhaland Territorial Administration

The DGHC did not fulfill its goal of forming a new state, which led to the downfall of Subhash Ghisingh and the rise of another party Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM) headed by Bimal Gurung in 2007, which launched a second agitation for a Gorkhaland state. After three years of agitation for a state of Gorkhaland led by GJM, the GJM reached an agreement with the state government to form a semi-autonomous body to administer the Darjeeling hills. The Memorandum of Agreement for Gorkhaland Territorial Administration(GTA) was signed on 18 July 2011 at Pintail Village near Siliguri in the presence of Union Home Minister P. Chidambaram, West Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee, the then Darjeeling Lok Sabha MP Jaswant Singh and Gorkha Janmukti Morcha leaders. The agreement was signed by West Bengal Home Secretary G.D. Gautama, Union Home Ministry Joint Secretary K.K. Pathak and Gorkha Janmukti Morcha general secretary Roshan Giri.

Notable people

Actors

- Rewati Chetri – Model and actress

- Ganesh – Kannada film actor[25]

- Bhumika Gurung – Television actress and model

- Bharti Singh – Comedian

- Niruta Singh – Actress in Nepali cinema

- Mala Sinha – Indian actress in Hindi and Bengali cinemas

- Pratibha Sinha – Bollywood Indian actress (daughter of actress Mala Sinha and Nepali actor C.P. Lohani)

- Geetanjali Thapa – Bollywood actress (National Film Award for Best Actress recipient 2013)

Cinematographers

Military

- Subedar Major Ganju Lama – Victoria cross recipient

- Major Durga Malla – Indian freedom fighter

- Trilochan Pokhrel – Indian freedom fighter

- Colonel Lalit Rai – Vir Chakra recipient for his actions in the Kargil War in 1999.

- Captain Ram Singh Thakuri – Indian freedom fighter who composed a number of patriotic songs including Kadam Kadam Badaye Ja

- Lieutenant-Colonel Dhan Singh Thapa – Param Vir Chakra recipient

- Brigadier Sher Jung Thapa (Hero of Skardu) – Mahavir Chakra recipient for his actions in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947

Musicians

- Louis Banks – Jazz musician

- Bipul Chettri – Singer, composer

- Ranjit Gazmer – Bollywood film musician

- Sukmit Gurung – Singer

- Aruna Lama – Nepali Singer from Darjeeling

- Udit Narayan – Playback singer

- Adrian Pradhan – Singer, songwriter, guitarist. Former 1974 AD member of Nepal

- Sonam Sherpa – Lead Guitarist of Parikrama band

- Poornima Shrestha – Bollywood playback singer

- Phiroj Shyangden – Singer, songwriter, guitarist. Former founding member of 1974 AD band of Nepal

- Prashant Tamang – Singer, actor, winner of Indian Idol Season 3

- Shanti Thatal – Composer, singer, producer

- Hira Devi Waiba – Pioneer of Nepali folk songs, singer

- Navneet Aditya Waiba – Folk singer

- Gopal Yonzon – Singer, musician, playwright

- Karma Yonzon – Composer, singer, producer

Athletics

Archery

- Tarundeep Rai – Archer, Asian Games 2011 silver medalist, Arjuna Award recipient 2005, Padma Shri recipient 2020

Boxing

- Birender Singh Thapa – Boxer

- Debendra Thapa – Boxer

- Shiva Thapa – Boxer (youngest Indian boxer to qualify for the Olympic Games)

Cricket

- Jay Bista – Cricketer

- Ruben Lepcha – Cricketer

- Gokul Sharma – Captain of Assam cricket team

- Abhishek Thakuri – Cricketer

Football

- Ajay Chhetri – Footballer

- Amar Bahadur Gurung – footballer

- Anirudh Thapa- footballer

- Anju Tamang – women's footballer

- Ashish Chettri – footballer

- Asish Rai – footballer

- Bijendra Rai – footballer

- Bikash Jairu – footballer

- Chandan Singh Rawat – footballer

- Israil Gurung – footballer

- Kamal Thapa – footballer

- Komal Thatal – footballer

- Lalit Thapa – goalkeeper

- Nagen Tamang – footballer

- Narender Thapa – footballer

- Nim Dorjee Tamang – footballer

- Nima Tamang – footballer

- Nirmal Chettri – footballer

- Pinky Bompal Magar – women's footballer

- Puran Bahadur Thapa – footballer

- Ram Bahadur Chettri – footballer

- Robin Gurung – footballer

- Sanju Pradhan – footballer, Mumbai City FC

- Shyam Thapa – footballer

- Sunil Chhetri – captain of the India national football team and Bengaluru FC. Recipient of Arjuna Award (2011) and Padma Shri (2019)

- Uttam Rai – footballer

- Vinit Rai – footballer

Hockey

- Bharat Chettri – Hockey player (former captain of Indian hockey team)

- Bir Bahadur Chettri – Hockey player

- Chaman Singh Gurung – Hockey player

Shooting

- Jitu Rai – Shooter, recipient of Arjuna Award (2015), Khel Ratna (2016) and Padma Shri (2020).

- Pemba Tamang – Shooter

Writers

- Indra Bahadur Rai – Nepali writer and literary critic from Darjeeling, India.

- Hari Prasad Gorkha Rai

- Kedar Gurung

- Kumar Pradhan

- Lil Bahadur Chettri – Padma Shri award recipient (2020) for his contribution towards Nepali literature.

- Prajwal Parajuly – English language writer and novelist

- Ganga Prasad Pradhan – Translator of the Nepali Bible, co-author of an English-Nepali dictionary, author of children's textbooks.

- Parijat real name Bishnu Kumari Waiba – Original writer of The Blue Mimosa Birthplace Darjeeling

- Agam Singh Giri – Nepali language poet and lyricist from Darjeeling.

- Birkha Bahadur Muringla -Padma Shri award recipient.

- Tulsiram Sharma Kashyap

Politicians

- Chobilal Upadhyaya – first president of the Assam Pradesh Congress Committee

- Shanta Chhetri – Member of Parliament

- B. B. Gurung – third Chief Minister of Sikkim.

- Bimal Gurung – Leader of Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM)

- Bishal Lama – MLA from Kalchini

- Bhaskar Sharma – MLA from Margherita, Assam

- Damber Singh Gurung – Indian Gorkha representative in the Constituent Assembly of India

- Dawa Narbula – Member of the Indian National Congress (INC), former Member of Parliament

- Ganesh Kumar Limbu – MLA from Barchalla, Assam

- Madan Tamang –Former President of Akhil Bharatiya Gorkha League (ABGL)

- Mala Rajya Laxmi Shah - Member of parliament from Tehri Garhwal

- Moni Kumar Subba – Member of INC , Assam

- Nar Bahadur Bhandari – Former Chief Minister of Sikkim

- Ram Prasad Sharma – MP of Tezpur

- Pawan Kumar Chamling – 5th Chief Minister of Sikkim, founder and president of Sikkim Democratic Front and the longest serving chief minister in India.[26]

- Prem Singh Tamang – Current Chief Minister of Sikkim, founder of Sikkim Krantikari Morcha.

- Prasanta Pradhan – CPI(M) Leader

- Prem Das Rai – Former Member of Parliament

- Subhash Ghisingh – Founder of Gorkhaland Movement in India and founder of political party GNLF

- Raju Bista – Member of Parliament from Darjeeling Lok Sabha constituency, 2019

- Dil Kumari Bhandari – former and first women member of parliament from Sikkim. Wife of former Chief Minister of Sikkim Narbahadur Bhandari. Birthplace Darjeeling

- Neeraj Zimba – MLA from Darjeeling and top leader of Gorkha National Liberation Front.

- Indra Hang Subba – Member of Parliament from Sikkim, elected in 2019.

- Ruden Sada Lepcha – MLA from Kalimpong

Others

- Balkrishna : Indian billionaire of Nepali origin

- Draupadi Ghimiray – Social activist, Padma Shri award recipient.

- Tulsi Ghimire – Film director/producer

- Mahendra P. Lama – Founding vice-chancellor of Sikkim University

- Nitesh R Pradhan – Journalist and singer

- Pratima Puri – First news reader of Doordarshan

- Rangu Souriya – Social worker

References

- "India and Nepal. Treaty of Peace and Friendship. Signed at Kathmandu" (PDF). untreaty.un.org. 31 July 1950. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2022.

- "Gorkhaland: Gazette Notification on the Issue of Citizenship of Gorkhas". Gorkhaland. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- rajbhasha.gov.in/en/languages-included-eighth-schedule-indian-constitution

- Barun Roy (2012). Gorkhas and Gorkhaland. Darjeeling, India: Parbati Roy Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 January 2013.

- "Growth of Scheduled Languages-1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001". Census of India. Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- "Language – Census of India" (PDF). Census of India. 2011. Retrieved 16 March 2023.

- "ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES – 2011" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 November 2018. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages – India/ States/ Union Territories-2011 Census" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- "Distribution of the 99 Non-Scheduled Languages- India/ States/ Union Territories-2011 Census" (PDF). censusindia.gov.in. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 February 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- "Thesis" (PDF). Shodganga. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 6 July 2022.

- "Economy, Ethnicity and Migration in Mehahalaya" (PDF). amanpanchayat.org. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2021. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- Karmakar, Rahul (18 November 2018). "Temples inspired by churches in Mizoram". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

- "ADBU Location". dbuniversity.ac.in. Archived from the original on 7 March 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "Demography". sikenvis.nic.in. Archived from the original on 6 July 2020. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- "Know all about the beautiful Mini Sikkim: Another beautiful gem in the seven sisters region". India Today. 10 February 2016. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "Watch | Sikkim: Simultaneous Elections and the Battle Over the 17th Karmapa". The Wire. 8 April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- "C-16 Population By Mother Tongue". censusindia.gov.in. Archived from the original on 3 November 2020. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- Mitra, Arnab (13 April 2021). "Tracing the history of Gorkhaland movement: Another crisis triggered by language". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 30 April 2022. Retrieved 30 April 2022.

- Samāddāra, Raṇabīra (2007). The Materiality of Politics: The technologies of rule. Anthem Press. ISBN 9781843312512. Archived from the original on 26 February 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Nepalis in Meghalaya face tribal wrath amid official apathy". Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- L. Nath (January 2005). "Migrants in flight: Conflict-induced induced displacement of Nepalis in Northeast India" (Occasional Paper). University of Cambridge. Retrieved 7 March 2023.

- "Khasi Nepali Ethnic Conflict in Meghalaya, India". 8 June 2010. Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Meghalaya rejects reports of violence against Nepalese". The Assam Tribune. 15 September 2010. Retrieved 29 August 2022.

- "The Parliament is the supreme and ultimate authority of India". Darjeeling Times. 23 November 2010. Archived from the original on 1 November 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2012.

- Lulla, Anil Budur (17 June 2007). "Gurkha Ganesh blazes new trail". www.telegraphindia.com. Archived from the original on 28 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- "Pawan Kumar Chamling crosses Jyoti Basu's record as longest-serving Chief Minister". The Hindu. 29 April 2018. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2020.