Central America

Central America[lower-alpha 2] is a subregion of the Americas.[2] Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the south, the Caribbean Sea to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Central America usually consists of seven countries: Belize, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. Within Central America is the Mesoamerican biodiversity hotspot, which extends from northern Guatemala to central Panama. Due to the presence of several active geologic faults and the Central America Volcanic Arc, there is a high amount of seismic activity in the region, such as volcanic eruptions and earthquakes which has resulted in death, injury, and property damage.

.svg.png.webp) | |

| Area | 523,780 km2 (202,230 sq mi)[1] |

|---|---|

| Population | 52,176,283 (2022)[1] |

| Population density | 99.6/km2 (258.0/sq mi) (2022) |

| GDP (PPP) | $370.52 billion (2013) |

| GDP (nominal) | $203.73 billion (exchange rate) (2013) |

| GDP per capita | $4,783 (exchange rate) (2013) $8,698 (PPP) (2013) |

| Demonym | Central American[lower-alpha 1] |

| Countries | |

| Dependencies | |

| Languages | |

| Time zones | UTC−06:00 to UTC−05:00 |

| Largest cities | |

| UN M49 code | 013 – Central America419 – Latin America and the Caribbean019 – Americas001 – World |

| Part of a series on |

| Central America |

|---|

|

In the pre-Columbian era, Central America was inhabited by the Indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica to the north and west and the Isthmo-Colombian peoples to the south and east. Following the Spanish expedition of Christopher Columbus' voyages to the Americas, Spain began to colonize the Americas. From 1609 to 1821, the majority of Central American territories (except for what would become Belize and Panama, and including the modern Mexican state of Chiapas) were governed by the viceroyalty of New Spain from Mexico City as the Captaincy General of Guatemala. On 24 August 1821, Spanish Viceroy Juan de O'Donojú signed the Treaty of Córdoba, which established New Spain's independence from Spain.[3] On 15 September 1821, the Act of Independence of Central America was enacted to announce Central America's separation from the Spanish Empire and provide for the establishment of a new Central American state. Some of New Spain's provinces in the Central American region (i.e. what would become Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica) were annexed to the First Mexican Empire; however in 1823 they seceded from Mexico to form the Federal Republic of Central America until 1838.[4]

In 1838, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua became the first of Central America's seven states to become independent countries, followed by El Salvador in 1841, Panama in 1903, and Belize in 1981.[5] Despite the dissolution of the Federal Republic of Central America, countries like Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua continue to maintain a Central American identity.[6] The Belizeans are usually identified as culturally Caribbean rather than Central American, while the Panamanians identify themselves more broadly with their South American neighbours.

The Spanish-speaking countries officially include both North America and South America as a single continent, América, which is split into four subregions: North America (Northern America and Mexico), Central America, South America, and Insular America (the West Indies).[7]

Different definitions

"Central America" may mean different things to various people, based upon different contexts:

- The non-official United Nations geoscheme for the Americas defines Central America as all states of mainland North America south of the United States, hence grouping Mexico as part of Central America for statistics purposes, but historically Mexico is considered North America.[8]

- Middle America is usually thought to comprise Mexico to the north of the 7 states of Central America as well as Colombia and Venezuela to the south. Usually, the whole of the Caribbean to the northeast, and sometimes the Guyanas, are also included. According to one source, the term "Central America" was used as a synonym for "Middle America" at least as recently as 1962.[9]

- In Ibero-America (Spanish and Portuguese speaking American countries), the Americas is considered a single continent (America), and Central America is considered a subregion of the continent comprising the seven countries south of Mexico and north of Colombia.

- For the people living in the five countries, formerly part of the Federal Republic of Central America there is a distinction between the Spanish language terms "América Central" and "Centroamérica". While both can be translated into English as "Central America", "América Central" is generally used to refer to the geographical area of the seven countries between Mexico and Colombia, while "Centroamérica" is used when referring to the former members of the Federation emphasizing the shared culture and history of the region.

- In Portuguese as a rule and occasionally in Spanish and other languages, the entirety of the Antilles is often included in the definition of Central America. Indeed, the Dominican Republic is a full member of the Central American Integration System.

History

- Ancient sites of Central America

Ancient footprints of Acahualinca, Nicaragua

Ancient footprints of Acahualinca, Nicaragua

Tazumal, El Salvador

Tazumal, El Salvador Tikal, Guatemala

Tikal, Guatemala Copan, Honduras

Copan, Honduras Altun Ha, Belize

Altun Ha, Belize

.jpg.webp)

Central America was formed more than 3 million years ago, as part of the Isthmus of Panama, when its portion of land connected each side of water.

In the Pre-Columbian era, the northern areas of Central America were inhabited by the indigenous peoples of Mesoamerica. Most notable among these were the Mayans, who had built numerous cities throughout the region, and the Aztecs, who had created a vast empire. The pre-Columbian cultures of eastern El Salvador, eastern Honduras, Caribbean Nicaragua, most of Costa Rica and Panama were predominantly speakers of the Chibchan languages at the time of European contact and are considered by some[10] culturally different and grouped in the Isthmo-Colombian Area.

Following the Spanish expedition of Christopher Columbus's voyages to the Americas, the Spanish sent many expeditions to the region, and they began their conquest of Maya territory in 1523. Soon after the conquest of the Aztec Empire, Spanish conquistador Pedro de Alvarado commenced the conquest of northern Central America for the Spanish Empire. Beginning with his arrival in Soconusco in 1523, Alvarado's forces systematically conquered and subjugated most of the major Maya kingdoms, including the K'iche', Tz'utujil, Pipil, and the Kaqchikel. By 1528, the conquest of Guatemala was nearly complete, with only the Petén Basin remaining outside the Spanish sphere of influence. The last independent Maya kingdoms – the Kowoj and the Itza people – were finally defeated in 1697, as part of the Spanish conquest of Petén.[11]

In 1538, Spain established the Real Audiencia of Panama, which had jurisdiction over all land from the Strait of Magellan to the Gulf of Fonseca. This entity was dissolved in 1543, and most of the territory within Central America then fell under the jurisdiction of the Audiencia Real de Guatemala. This area included the current territories of Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Mexican state of Chiapas, but excluded the lands that would become Belize and Panama. The president of the Audiencia, which had its seat in Antigua Guatemala, was the governor of the entire area. In 1609 the area became a captaincy general and the governor was also granted the title of captain general. The Captaincy General of Guatemala encompassed most of Central America, with the exception of present-day Belize and Panama.

The Captaincy General of Guatemala lasted for more than two centuries, but began to fray after a rebellion in 1811 which began in the Intendancy of San Salvador. The Captaincy General formally ended on 15 September 1821, with the signing of the Act of Independence of Central America. Mexican independence was achieved at virtually the same time with the signing of the Treaty of Córdoba and the Declaration of Independence of the Mexican Empire, and the entire region was finally independent from Spanish authority by 28 September 1821.

Historic flags of Central American Unions

United Provinces of Central America (1823–1825)

United Provinces of Central America (1823–1825).png.webp) The United States of the Center of America (1826)

The United States of the Center of America (1826) Federal Republic of Central America (1827–1841)

Federal Republic of Central America (1827–1841) Federal Republic of Central America (1842–1845)

Federal Republic of Central America (1842–1845) Central American Federation 1851–1853

Central American Federation 1851–1853 Greater Republic of Central America (1896–1897)

Greater Republic of Central America (1896–1897).svg.png.webp) Greater Republic of Central America (1897–1898)

Greater Republic of Central America (1897–1898) Republic of Central America (1921–1922)

Republic of Central America (1921–1922)

Historic coat of arms of Central American Unions

The United Provinces of Central America (1823–1825)

The United Provinces of Central America (1823–1825).png.webp) United States of Central America (1826)

United States of Central America (1826) Federal Republic of Central America (1827–1841)

Federal Republic of Central America (1827–1841) Federal Republic of Central America (1842–1845)

Federal Republic of Central America (1842–1845) Federation of Central America (1851–1853)

Federation of Central America (1851–1853) The Greater Republic of Central America (1896–1897)

The Greater Republic of Central America (1896–1897).svg.png.webp) Greater Republic of Central America (1897–1898)

Greater Republic of Central America (1897–1898) Republic of Central America (1921–1922)

Republic of Central America (1921–1922)

.jpg.webp)

From its independence from Spain in 1821 until 1823, the former Captaincy General remained intact as part of the short-lived First Mexican Empire. When the Emperor of Mexico abdicated on 19 March 1823, Central America again became independent. On 1 July 1823, the Congress of Central America peacefully seceded from Mexico and declared absolute independence from all foreign nations, and the region formed the Federal Republic of Central America.

The Federal Republic of Central America was a representative democracy with its capital at Guatemala City. This union consisted of the provinces of Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Los Altos, Mosquito Coast, and Nicaragua. The lowlands of southwest Chiapas, including Soconusco, initially belonged to the Republic until 1824, when Mexico annexed most of Chiapas and began its claims to Soconusco. The Republic lasted from 1823 to 1838, when it disintegrated as a result of civil wars.

The territory that now makes up Belize was heavily contested in a dispute that continued for decades after Guatemala achieved independence. Spain, and later Guatemala, considered this land a Guatemalan department. In 1862, Britain formally declared it a British colony and named it British Honduras. It became independent as Belize in 1981.[5]

Panama, situated in the southernmost part of Central America on the Isthmus of Panama, has for most of its history been culturally and politically linked to South America. Panama was part of the Province of Tierra Firme from 1510 until 1538 when it came under the jurisdiction of the newly formed Audiencia Real de Panama. Beginning in 1543, Panama was administered as part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, along with all other Spanish possessions in South America. Panama remained as part of the Viceroyalty of Peru until 1739, when it was transferred to the Viceroyalty of New Granada, the capital of which was located at Santa Fé de Bogotá. Panama remained as part of the Viceroyalty of New Granada until the disestablishment of that viceroyalty in 1819. A series of military and political struggles took place from that time until 1822, the result of which produced the republic of Gran Colombia. After the dissolution of Gran Colombia in 1830, Panama became part of a successor state, the Republic of New Granada. From 1855 until 1886, Panama existed as Panama State, first within the Republic of New Granada, then within the Granadine Confederation, and finally within the United States of Colombia. The United States of Colombia was replaced by the Republic of Colombia in 1886. As part of the Republic of Colombia, Panama State was abolished and it became the Isthmus Department. Despite the many political reorganizations, Colombia was still deeply plagued by conflict, which eventually led to the secession of Panama on 3 November 1903. Only after that time did some begin to regard Panama as a North or Central American entity.

By the 1930s the United Fruit Company owned 14,000 square kilometres (3.5 million acres) of land in Central America and the Caribbean and was the single largest land owner in Guatemala. Such holdings gave it great power over the governments of small countries. That was one of the factors that led to the coining of the phrase banana republic.[12]

After more than two hundred years of social unrest, violent conflict, and revolution, Central America today remains in a period of political transformation. Poverty, social injustice, and violence are still widespread.[13] Nicaragua is the second poorest country in the western hemisphere (only Haiti is poorer).[14]

Flags of modern Central America

Coat of arms of modern Central America

Geography

Central America is a part of North America consisting of a tapering isthmus running from the southern extent of Mexico to the northwestern portion of South America. Central America has the Gulf of Mexico, a body of water within the Atlantic Ocean, to the north; the Caribbean Sea, also part of the Atlantic Ocean, to the northeast; and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Some physiographists define the Isthmus of Tehuantepec as the northern geographic border of Central America,[15] while others use the northwestern borders of Belize and Guatemala. From there, the Central American land mass extends southeastward to the Atrato River, where it connects to the Pacific Lowlands in northwestern South America.

Of the many mountain ranges within Central America, the longest are the Sierra Madre de Chiapas, the Cordillera Isabelia and the Cordillera de Talamanca. At 4,220 meters (13,850 ft), Volcán Tajumulco is the highest peak in Central America. Other high points of Central America are as listed in the table below:

| Country | Name | Elevation (meters) | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doyle's Delight | 1,124 | Cockscomb Range | |

| Cerro Chirripó | 3,820 | Cordillera de Talamanca | |

| Cerro El Pital | 2,730 | Sierra Madre de Chiapas | |

| Volcán Tajumulco | 4,220 | Sierra Madre de Chiapas | |

| Cerro Las Minas | 2,780 | Cordillera de Celaque | |

| Mogotón | 2,107 | Cordillera Isabelia | |

| Volcán Barú | 3,474 | Cordillera de Talamanca |

Between the mountain ranges lie fertile valleys that are suitable for the raising of livestock and for the production of coffee, tobacco, beans and other crops. Most of the population of Honduras, Costa Rica and Guatemala lives in valleys.[16]

Trade winds have a significant effect upon the climate of Central America. Temperatures in Central America are highest just prior to the summer wet season, and are lowest during the winter dry season, when trade winds contribute to a cooler climate. The highest temperatures occur in April, due to higher levels of sunlight, lower cloud cover and a decrease in trade winds.[17]

Biodiversity

Central American forests

.jpg.webp) Belize

Belize Montecristo National Park, El Salvador

Montecristo National Park, El Salvador Maderas forest, Nicaragua

Maderas forest, Nicaragua Texiguat Wildlife Refuge Honduras

Texiguat Wildlife Refuge Honduras Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, Costa Rica.

Monteverde Cloud Forest Reserve, Costa Rica. Parque Internacional la Amistad, Panama

Parque Internacional la Amistad, Panama Petén–Veracruz moist forests, Guatemala

Petén–Veracruz moist forests, Guatemala

Central America is part of the Mesoamerican biodiversity hotspot, boasting 7% of the world's biodiversity.[18] The Pacific Flyway is a major north–south flyway for migratory birds in the Americas, extending from Alaska to Tierra del Fuego. Due to the funnel-like shape of its land mass, migratory birds can be seen in very high concentrations in Central America, especially in the spring and autumn. As a bridge between North America and South America, Central America has many species from the Nearctic and the Neotropical realms. However the southern countries (Costa Rica and Panama) of the region have more biodiversity than the northern countries (Guatemala and Belize), meanwhile the central countries (Honduras, Nicaragua and El Salvador) have the least biodiversity.[18] The table below shows recent statistics:

| Country | Amphibian species |

Bird species |

Mammal species |

Reptile species |

Total terrestrial vertebrate species |

Vascular plants species |

Biodiversity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize[19] | 46 | 544 | 147 | 140 | 877 | 2894 | 3771 |

| Costa Rica[20] | 183 | 838 | 232 | 258 | 1511 | 12119 | 13630 |

| El Salvador[21] | 30 | 434 | 137 | 106 | 707 | 2911 | 3618 |

| Guatemala[22] | 133 | 684 | 193 | 236 | 1246 | 8681 | 9927 |

| Honduras[23] | 101 | 699 | 201 | 213 | 1214 | 5680 | 6894 |

| Nicaragua[24] | 61 | 632 | 181 | 178 | 1052 | 7590 | 8642 |

| Panama[25] | 182 | 904 | 241 | 242 | 1569 | 9915 | 11484 |

Over 300 species of the region's flora and fauna are threatened, 107 of which are classified as critically endangered. The underlying problems are deforestation, which is estimated by FAO at 1.2% per year in Central America and Mexico combined, fragmentation of rainforests and the fact that 80% of the vegetation in Central America has already been converted to agriculture.[26]

Efforts to protect fauna and flora in the region are made by creating ecoregions and nature reserves. 36% of Belize's land territory falls under some form of official protected status, giving Belize one of the most extensive systems of terrestrial protected areas in the Americas. In addition, 13% of Belize's marine territory are also protected.[27] A large coral reef extends from Mexico to Honduras: the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef System. The Belize Barrier Reef is part of this. The Belize Barrier Reef is home to a large diversity of plants and animals, and is one of the most diverse ecosystems of the world. It is home to 70 hard coral species, 36 soft coral species, 500 species of fish and hundreds of invertebrate species. So far only about 10% of the species in the Belize barrier reef have been discovered.[28]

National flowers of Central America

Lycaste skinneri, Guatemala

Lycaste skinneri, Guatemala.jpg.webp) Izote flower, El Salvador

Izote flower, El Salvador.jpg.webp) Rhyncholaelia digbyana, Honduras

Rhyncholaelia digbyana, Honduras Plumeria, Nicaragua

Plumeria, Nicaragua Guarianthe skinneri, Costa Rica

Guarianthe skinneri, Costa Rica Peristeria elata, Panama

Peristeria elata, Panama Prosthechea cochleata, Belize

Prosthechea cochleata, Belize

National trees of Central America

Enterolobium cyclocarpum Costa Rica

Enterolobium cyclocarpum Costa Rica Tabebuia rosea El Salvador

Tabebuia rosea El Salvador Sterculia apetala Panama

Sterculia apetala Panama Pinus oocarpa Honduras

Pinus oocarpa Honduras Calycophyllum candidissimum Nicaragua

Calycophyllum candidissimum Nicaragua Swietenia macrophylla Belize

Swietenia macrophylla Belize Ceiba Guatemala

Ceiba Guatemala

From 2001 to 2010, 5,376 square kilometers (2,076 sq mi) of forest were lost in the region. In 2010 Belize had 63% of remaining forest cover, Costa Rica 46%, Panama 45%, Honduras 41%, Guatemala 37%, Nicaragua 29%, and El Salvador 21%. Most of the loss occurred in the moist forest biome, with 12,201 square kilometers (4,711 sq mi). Woody vegetation loss was partially set off by a gain in the coniferous forest biome with 4,730 square kilometers (1,830 sq mi), and a gain in the dry forest biome at 2,054 square kilometers (793 sq mi). Mangroves and deserts contributed only 1% to the loss in forest vegetation. The bulk of the deforestation was located at the Caribbean slopes of Nicaragua with a loss of 8,574 square kilometers (3,310 sq mi) of forest in the period from 2001 to 2010. The most significant regrowth of 3,050 square kilometers (1,180 sq mi) of forest was seen in the coniferous woody vegetation of Honduras.[29]

Montane forests

The Central American pine-oak forests ecoregion, in the tropical and subtropical coniferous forests biome, is found in Central America and southern Mexico. The Central American pine-oak forests occupy an area of 111,400 square kilometers (43,000 sq mi),[30] extending along the mountainous spine of Central America, extending from the Sierra Madre de Chiapas in Mexico's Chiapas state through the highlands of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras to central Nicaragua. The pine-oak forests lie between 600–1,800 metres (2,000–5,900 ft) elevation,[30] and are surrounded at lower elevations by tropical moist forests and tropical dry forests. Higher elevations above 1,800 metres (5,900 ft) are usually covered with Central American montane forests. The Central American pine-oak forests are composed of many species characteristic of temperate North America including oak, pine, fir, and cypress.

Laurel forest is the most common type of Central American temperate evergreen cloud forest, found in almost all Central American countries, normally more than 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) above sea level. Tree species include evergreen oaks, members of the laurel family, species of Weinmannia and Magnolia, and Drimys granadensis.[31] The cloud forest of Sierra de las Minas, Guatemala, is the largest in Central America. In some areas of southeastern Honduras there are cloud forests, the largest located near the border with Nicaragua. In Nicaragua, cloud forests are situated near the border with Honduras, but many were cleared to grow coffee. There are still some temperate evergreen hills in the north. The only cloud forest in the Pacific coastal zone of Central America is on the Mombacho volcano in Nicaragua. In Costa Rica, there are laurel forests in the Cordillera de Tilarán and Volcán Arenal, called Monteverde, also in the Cordillera de Talamanca.

The Central American montane forests are an ecoregion of the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome, as defined by the World Wildlife Fund.[32] These forests are of the moist deciduous and the semi-evergreen seasonal subtype of tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests and receive high overall rainfall with a warm summer wet season and a cooler winter dry season. Central American montane forests consist of forest patches located at altitudes ranging from 1,800–4,000 metres (5,900–13,100 ft), on the summits and slopes of the highest mountains in Central America ranging from Southern Mexico, through Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras, to northern Nicaragua. The entire ecoregion covers an area of 13,200 square kilometers (5,100 sq mi) and has a temperate climate with relatively high precipitation levels.[32]

Fauna

Legendary National Birds of Central America

Resplendent quetzal, Guatemala

Resplendent quetzal, Guatemala Turquoise-browed motmot, El Salvador and Nicaragua

Turquoise-browed motmot, El Salvador and Nicaragua Keel-billed toucan, Belize

Keel-billed toucan, Belize Scarlet macaw, Honduras

Scarlet macaw, Honduras Clay-colored thrush, Costa Rica

Clay-colored thrush, Costa Rica Harpy eagle, Panama

Harpy eagle, Panama

Ecoregions are not only established to protect the forests themselves but also because they are habitats for an incomparably rich and often endemic fauna. Almost half of the bird population of the Talamancan montane forests in Costa Rica and Panama are endemic to this region. Several birds are listed as threatened, most notably the resplendent quetzal (Pharomacrus mocinno), three-wattled bellbird (Procnias tricarunculata), bare-necked umbrellabird (Cephalopterus glabricollis), and black guan (Chamaepetes unicolor). Many of the amphibians are endemic and depend on the existence of forest. The golden toad that once inhabited a small region in the Monteverde Reserve, which is part of the Talamancan montane forests, has not been seen alive since 1989 and is listed as extinct by IUCN. The exact causes for its extinction are unknown. Global warming may have played a role, because the development of that frog is typical for this area may have been compromised. Seven small mammals are endemic to the Costa Rica-Chiriqui highlands within the Talamancan montane forest region. Jaguars, cougars, spider monkeys, as well as tapirs, and anteaters live in the woods of Central America.[31] The Central American red brocket is a brocket deer found in Central America's tropical forest.

Geology

- Central American Geology

Coatepeque Caldera, El Salvador

Coatepeque Caldera, El Salvador.jpg.webp) Lake Atitlán, Guatemala

Lake Atitlán, Guatemala Mombacho, Nicaragua

Mombacho, Nicaragua Arenal Volcano, Costa Rica

Arenal Volcano, Costa Rica

Central America is geologically very active, with volcanic eruptions and earthquakes occurring frequently, and tsunamis occurring occasionally. Many thousands of people have died as a result of these natural disasters.

Most of Central America rests atop the Caribbean Plate. This tectonic plate converges with the Cocos, Nazca, and North American plates to form the Middle America Trench, a major subduction zone. The Middle America Trench is situated some 60–160 kilometers (37–99 mi) off the Pacific coast of Central America and runs roughly parallel to it. Many large earthquakes have occurred as a result of seismic activity at the Middle America Trench.[33] For example, subduction of the Cocos Plate beneath the North American Plate at the Middle America Trench is believed to have caused the 1985 Mexico City earthquake that killed as many as 40,000 people. Seismic activity at the Middle America Trench is also responsible for earthquakes in 1902, 1942, 1956, 1982, 1992, January 2001, February 2001, 2007, 2012, 2014, and many other earthquakes throughout Central America.

The Middle America Trench is not the only source of seismic activity in Central America. The Motagua Fault is an onshore continuation of the Cayman Trough which forms part of the tectonic boundary between the North American Plate and the Caribbean Plate. This transform fault cuts right across Guatemala and then continues offshore until it merges with the Middle America Trench along the Pacific coast of Mexico, near Acapulco. Seismic activity at the Motagua Fault has been responsible for earthquakes in 1717, 1773, 1902, 1976, 1980, and 2009.

Another onshore continuation of the Cayman Trough is the Chixoy-Polochic Fault, which runs parallel to, and roughly 80 kilometers (50 mi) to the north, of the Motagua Fault. Though less active than the Motagua Fault, seismic activity at the Chixoy-Polochic Fault is still thought to be capable of producing very large earthquakes, such as the 1816 earthquake of Guatemala.[34]

Managua, the capital of Nicaragua, was devastated by earthquakes in 1931 and 1972.

Volcanic eruptions are also common in Central America. In 1968 the Arenal Volcano, in Costa Rica, erupted killing 87 people as the 3 villages of Tabacon, Pueblo Nuevo and San Luis were buried under pyroclastic flows and debris. Fertile soils from weathered volcanic lava have made it possible to sustain dense populations in the agriculturally productive highland areas.

Demographics

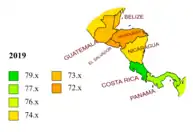

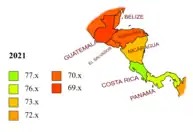

Life expectancy

List of countries by life expectancy at birth for 2021, according to the World Bank Group.[35][36][37] List of Central American countries is expanded by Mexico and Colombia.

| Countries & territories |

2021 | Historical data | COVID-19 impact | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Male | Female | Gender gap |

2000 | 2000 →2014 |

2014 | 2014 →2019 |

2019 | 2019 →2020 |

2020 | 2020 →2021 |

2021 | 2019 →2021 |

2014 →2021 | |

| 77.02 | 74.42 | 79.81 | 5.39 | 77.59 | 1.19 | 78.77 | 0.65 | 79.43 | −0.15 | 79.28 | −2.25 | 77.02 | −2.40 | −1.75 | |

| 76.22 | 73.05 | 79.59 | 6.54 | 74.00 | 3.25 | 77.25 | 0.56 | 77.81 | −1.15 | 76.66 | −0.43 | 76.22 | −1.59 | −1.03 | |

| 73.84 | 70.84 | 76.80 | 5.97 | 67.23 | 5.58 | 72.81 | 1.24 | 74.05 | −2.26 | 71.80 | 2.04 | 73.84 | −0.22 | 1.03 | |

| 72.83 | 69.40 | 76.44 | 7.04 | 71.32 | 4.72 | 76.04 | 0.71 | 76.75 | −1.98 | 74.77 | −1.94 | 72.83 | −3.92 | −3.21 | |

| World | 71.33 | 68.89 | 73.95 | 5.06 | 67.70 | 4.18 | 71.88 | 1.10 | 72.98 | −0.74 | 72.24 | −0.92 | 71.33 | −1.65 | −0.55 |

| 70.75 | 66.08 | 75.15 | 9.07 | 69.86 | 1.88 | 71.75 | 0.81 | 72.56 | −1.50 | 71.06 | −0.31 | 70.75 | −1.81 | −1.00 | |

| 70.47 | 67.12 | 74.33 | 7.21 | 68.56 | 4.75 | 73.31 | 0.62 | 73.93 | −1.08 | 72.85 | −2.38 | 70.47 | −3.46 | −2.84 | |

| 70.21 | 66.06 | 74.86 | 8.81 | 73.57 | 1.23 | 74.80 | −0.59 | 74.20 | −4.07 | 70.13 | 0.08 | 70.21 | −3.99 | −4.58 | |

| 70.12 | 67.89 | 72.53 | 4.64 | 68.66 | 3.60 | 72.26 | 0.62 | 72.88 | −1.42 | 71.46 | −1.34 | 70.12 | −2.76 | −2.14 | |

| 69.24 | 66.00 | 72.65 | 6.65 | 67.45 | 4.52 | 71.96 | 1.17 | 73.13 | −1.33 | 71.80 | −2.56 | 69.24 | −3.89 | −2.73 | |

Capital cities of Central America

The population of Central America is estimated at 50,956,791 as of 2021.[38][39] With an area of 523,780 square kilometers (202,230 sq mi),[40] it has a population density of 97.3 per square kilometre (252 per square mile). Human Development Index values are from the estimates for 2017.[41]

| Country | Area (km2)[42] |

Population (2021 est.)[38][39] |

Population density (per km2) |

Capital | Official language |

Human Development Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | 22,966 | 400,031 | 17 | Belmopan | English | 0.708 High |

| Costa Rica | 51,100 | 5,153,957 | 101 | San José | Spanish | 0.794 High |

| El Salvador | 21,041 | 6,314,167 | 300 | San Salvador | Spanish | 0.674 Medium |

| Guatemala | 108,889 | 17,608,483 | 162 | Guatemala City | Spanish | 0.650 Medium |

| Honduras | 112,090 | 10,278,345 | 92 | Tegucigalpa | Spanish | 0.617 Medium |

| Nicaragua | 130,370 | 6,850,540 | 53 | Managua | Spanish | 0.658 Medium |

| Panama | 75,420 | 4,351,267 | 58 | Panama City | Spanish | 0.789 High |

| Total | 521,876 | 50,956,790 | - | - | - | 0.699 |

| City | Country | Population | Census Year | % of National Population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Guatemala City | Guatemala | 5,700,000 | 2010 | 26% |

| San Salvador | El Salvador | 2,415,217 | 2009 | 39% |

| Managua | Nicaragua | 2,045,000 | 2012 | 34% |

| Tegucigalpa | Honduras | 1,819,000 | 2010 | 24% |

| San Pedro Sula | Honduras | 1,600,000 | 2010 | 21%+4 |

| Panama City | Panama | 1,400,000 | 2010 | 37% |

| San José | Costa Rica | 1,275,000 | 2013 | 30% |

Languages

The official language majority in all Central American countries is Spanish, except in Belize, where the official language is English. Mayan languages constitute a language family consisting of about 26 related languages. Guatemala formally recognized 21 of these in 1996. Xinca, Miskito, and Garifuna are also present in Central America.

| Rank | Countries | Population | % Spanish | % Mayan languages | % English | % Xinca | % Garifuna |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Guatemala | 17,284,000 | 64.7% | 34.3% | 0.0% | 0.7% | 0.3% |

| 2 | Honduras | 8,447,000 | 97.1% | 2.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.9% |

| 3 | El Salvador | 6,108,000 | 99.0% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 4 | Nicaragua | 6,028,000 | 87.4% | 7.1% | 5.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 5 | Costa Rica | 4,726,000 | 97.2% | 1.8% | 1.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 6 | Panamá | 3,652,000 | 86.8% | 0.0% | 4.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 7 | Belize | 408,867 | 34.1% | 8.9% | 57.0% | 0.0% | 2.0% |

Ethnic groups

This region of the continent is very rich in terms of ethnic groups. The majority of the population is mestizo, with sizable Mayan and African descendent populations present, along with numerous other indigenous groups such as the Miskito people. The immigration of Arabs, Jews, Chinese, Europeans and others brought additional groups to the area.

| Country | Population1 | % Amerindian | % White | % Mestizo/Mixed | % Black | % Other |

| Belize | 324,528 | 6.3% | 5.0% | 49.6% | 32.0% | 4.1% |

| Costa Rica | 4,301,712 | 4.0% | 82.3% | 15.7% | 1.3% | 0.7% |

| El Salvador | 6,340,889 | 1.0% | 12.0% | 86.0% | 0.0% | 1.0% |

| Guatemala | 15,700,000 | 42.0% | 4.0% | 53.0% | 0.2% | 0.8% |

| Honduras | 8,143,564 | 6.0% | 5.5% | 82.0% | 6.0% | 0.5% |

| Nicaragua | 5,815,500 | 5.0% | 17.0% | 69.0% | 9.0% | 0.0% |

| Panama | 3,474,562 | 6.0% | 10.0% | 65.0% | 14.0% | 5.0% |

| Total | 42,682,190 | 10.04% | 17.04% | 59.77% | 9.77% | 2.91% |

Religious groups

Cathedrals of Central America

Immaculate Conception Cathedral, Managua Nicaragua

Immaculate Conception Cathedral, Managua Nicaragua San Salvador Cathedral El Salvador

San Salvador Cathedral El Salvador Cathedral of Guatemala City Guatemala

Cathedral of Guatemala City Guatemala Metropolitan Cathedral of San José Costa Rica

Metropolitan Cathedral of San José Costa Rica

Tegucigalpa Cathedral Honduras

Tegucigalpa Cathedral Honduras Holy Redeemer Cathedral Belize

Holy Redeemer Cathedral Belize

The predominant religion in Central America is Christianity (95.6%).[43] Beginning with the Spanish colonization of Central America in the 16th century, Roman Catholicism became the most popular religion in the region until the first half of the 20th century. Since the 1960s, there has been an increase in other Christian groups, particularly Protestantism, as well as other religious organizations, and individuals identifying themselves as having no religion.[44]

| Country | Roman Catholicism (2020) | Protestantism (2020) | Other Christian (2020) | Non Affiliated (2020) | Other (2020) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | 47.4% | 34.5% | 7.1% | 6.8% | 3.2% |

| Costa Rica | 72.5% | 19.5% | 2.4% | 4.5% | 1.1% |

| El Salvador | 55.8% | 35.3% | 3.6% | 5.0% | 0.3% |

| Guatemala | 55.4% | 25.9% | 14.3% | 4.0% | 0.4% |

| Honduras | 64.9% | 29.1% | 2.2% | 3.1% | 0.7% |

| Nicaragua | 58.3% | 36.7% | 1.4% | 3.4% | 0.1% |

| Panama | 66.1% | 23.9% | 1.8% | 4.2% | 3.0% |

Source: Jason Mandrik, Operation World Statistics (2020).

- Protestantism in Central America also include Independent Christian, most of total Protestants in this region (+80%) are Evangelicals, the rest follow traditional beliefs.

- Other Christian include Other Traditional Churches (Orthodox, Episcopalian, etc.) and contemporary churches (Mormons, Adventists, Scientology, etc.), also include Non-denominational Christian who are the most numerous group, specially in Guatemala.

Culture

Central American art

Guatemalan textiles

Guatemalan textiles Mola (art form), Panama

Mola (art form), Panama El Salvador La Plama art form

El Salvador La Plama art form

National dishes of Central America

Baleada Honduras

Baleada Honduras Pupusa El Salvador

Pupusa El Salvador Sancocho Panama

Sancocho Panama Gallo pinto Costa Rica

Gallo pinto Costa Rica Nacatamal Nicaragua

Nacatamal Nicaragua Rice and beans Belize

Rice and beans Belize Pepián Guatemala

Pepián Guatemala

Sport

- Central American Games

- Central American and Caribbean Games

- 1926 Central American and Caribbean Games – the first time this event occurred

- Central American Football Union

- Surfing

Politics

Leaders of Central America

_(cropped).png.webp) Alejandro Giammattei Guatemala

Alejandro Giammattei Guatemala.jpg.webp) Nayib Bukele El Salvador

Nayib Bukele El Salvador.jpg.webp) Xiomara Castro Honduras

Xiomara Castro Honduras.jpg.webp) Daniel Ortega Nicaragua

Daniel Ortega Nicaragua.jpg.webp) Rodrigo Chaves Robles Costa Rica

Rodrigo Chaves Robles Costa Rica.jpg.webp) Laurentino Cortizo Panama

Laurentino Cortizo Panama_(cropped).jpg.webp) Johnny Briceño Belize

Johnny Briceño Belize

Integration

Coat of arms

| |

| Motto: "Peace, Development, Liberty and Democracy" | |

| Anthem: La Granadera | |

| Countries |

|

| Area | |

• Total | 523,780[1] km2 (202,230 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | 52,176,283[1] |

• Density | 99.6/km2 (258.0/sq mi) |

Central America is currently undergoing a process of political, economic and cultural transformation that started in 1907 with the creation of the Central American Court of Justice.

In 1951 the integration process continued with the signature of the San Salvador Treaty, which created the ODECA, the Organization of Central American States. However, the unity of the ODECA was limited by conflicts between several member states.

In 1991, the integration agenda was further advanced by the creation of the Central American Integration System (Sistema para la Integración Centroamericana, or SICA). SICA provides a clear legal basis to avoid disputes between the member states. SICA membership includes the 7 nations of Central America plus the Dominican Republic, a state that is traditionally considered part of the Caribbean.

On 6 December 2008, SICA announced an agreement to pursue a common currency and common passport for the member nations.[45] No timeline for implementation was discussed.

Central America already has several supranational institutions such as the Central American Parliament, the Central American Bank for Economic Integration and the Central American Common Market.

On 22 July 2011, President Mauricio Funes of El Salvador became the first president pro tempore to SICA. El Salvador also became the headquarters of SICA with the inauguration of a new building.[46]

Foreign relations

Until recently, all Central American countries maintained diplomatic relations with Taiwan instead of China. President Óscar Arias of Costa Rica, however, established diplomatic relations with China in 2007, severing formal diplomatic ties with Taiwan.[47] After breaking off relations with the Republic of China in 2017, Panama established diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China. In August 2018, El Salvador also severed ties with Taiwan to formally start recognizing the People's Republic of China as sole China, a move many considered lacked transparency due to its abruptness and reports of the Chinese government's desires to invest in the department of La Union while also promising to fund the ruling party's reelection campaign.[48] The President of El Salvador, Nayib Bukele, broke diplomatic relations with Taiwan and established ties with China. On 9 December 2021, Nicaragua resumed relations with the PRC.[49]

Parliament

The Central American Parliament (aka PARLACEN) is a political and parliamentary body of SICA. The parliament started around 1980, and its primary goal was to resolve conflicts in Nicaragua, Guatemala, and El Salvador. Although the group was disbanded in 1986, ideas of unity of Central Americans still remained, so a treaty was signed in 1987 to create the Central American Parliament and other political bodies. Its original members were Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Honduras. The parliament is the political organ of Central America, and is part of SICA. New members have since then joined including Panama and the Dominican Republic.

Costa Rica is not a member State of the Central American Parliament and its adhesion remains as a very unpopular topic at all levels of the Costa Rican society due to existing strong political criticism towards the regional parliament, since it is regarded by Costa Ricans as a menace to democratic accountability and effectiveness of integration efforts. Excessively high salaries for its members, legal immunity of jurisdiction from any member State, corruption, lack of a binding nature and effectiveness of the regional parliament's decisions, high operative costs and immediate membership of Central American Presidents once they leave their office and presidential terms, are the most common reasons invoked by Costa Ricans against the Central American Parliament.

Economy

Signed in 2004, the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) is an agreement between the United States, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and the Dominican Republic. The treaty is aimed at promoting free trade among its members.

Guatemala has the largest economy in the region.[50][51] Its main exports are coffee, sugar, bananas, petroleum, clothing, and cardamom. Of its 10.29 billion dollar annual exports,[52] 40.2% go to the United States, 11.1% to neighboring El Salvador, 8% to Honduras, 5.5% to Mexico, 4.7% to Nicaragua, and 4.3% to Costa Rica.[53]

The region is particularly attractive for companies (especially clothing companies) because of its geographical proximity to the United States, very low wages and considerable tax advantages. In addition, the decline in the prices of coffee and other export products and the structural adjustment measures promoted by the international financial institutions have partly ruined agriculture, favouring the emergence of maquiladoras. This sector accounts for 42 per cent of total exports from El Salvador, 55 per cent from Guatemala, and 65 per cent from Honduras. However, its contribution to the economies of these countries is disputed; raw materials are imported, jobs are precarious and low-paid, and tax exemptions weaken public finances.[54]

They are also criticised for the working conditions of employees: insults and physical violence, abusive dismissals (especially of pregnant workers), working hours, non-payment of overtime. According to Lucrecia Bautista, coordinator of the maquilas sector of the audit firm Coverco, labour law regulations are regularly violated in maquilas and there is no political will to enforce their application. In the case of infringements, the labour inspectorate shows remarkable leniency. It is a question of not discouraging investors. Trade unionists are subject to pressure, and sometimes to kidnapping or murder. In some cases, business leaders have used the services of the maras. Finally, black lists containing the names of trade unionists or political activists are circulating in employers' circles.[54]

Economic growth in Central America is projected to slow slightly in 2014–15, as country-specific domestic factors offset the positive effects from stronger economic activity in the United States.[55]

| Country | GDP (nominal)[50][lower-alpha 3] | GDP (nominal) per capita[56][57] | GDP (PPP)[51][lower-alpha 3] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belize | 1,552 | $4,602 | 2,914 |

| Costa Rica | 44,313 | $10,432 | 57,955 |

| El Salvador | 24,421 | $3,875 | 46,050 |

| Guatemala | 50,303 | $3,512 | 78,012 |

| Honduras | 18,320 | $2,323 | 37,408 |

| Nicaragua | 7,695 | $1,839 | 19,827 |

| Panama | 34,517 | $10,838 | 55,124 |

Tourism

Central American coast

Playa Blanca Guatemala

Playa Blanca Guatemala Jiquilisco Bay, El Salvador

Jiquilisco Bay, El Salvador Roatán, Honduras

Roatán, Honduras Pink Pearl Island Nicaragua

Pink Pearl Island Nicaragua Tamarindo, Costa Rica

Tamarindo, Costa Rica Cayos Zapatilla, Panama

Cayos Zapatilla, Panama Corozal Beach, Belize

Corozal Beach, Belize

Tourism in Belize has grown considerably in more recent times, and it is now the second largest industry in the nation. Belizean Prime Minister Dean Barrow has stated his intention to use tourism to combat poverty throughout the country.[58] The growth in tourism has positively affected the agricultural, commercial, and finance industries, as well as the construction industry. The results for Belize's tourism-driven economy have been significant, with the nation welcoming almost one million tourists in a calendar year for the first time in its history in 2012.[59] Belize is also the only country in Central America with English as its official language, making this country a comfortable destination for English-speaking tourists.[60]

Costa Rica is the most visited nation in Central America.[61] Tourism in Costa Rica is one of the fastest growing economic sectors of the country,[62] having become the largest source of foreign revenue by 1995.[63] Since 1999, tourism has earned more foreign exchange than bananas, pineapples and coffee exports combined.[64] The tourism boom began in 1987,[63] with the number of visitors up from 329,000 in 1988, through 1.03 million in 1999, to a historical record of 2.43 million foreign visitors and $1.92-billion in revenue in 2013.[61] In 2012 tourism contributed with 12.5% of the country's GDP and it was responsible for 11.7% of direct and indirect employment.[65]

Tourism in Nicaragua has grown considerably recently, and it is now the second largest industry in the nation. Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega has stated his intention to use tourism to combat poverty throughout the country.[66] The growth in tourism has positively affected the agricultural, commercial, and finance industries, as well as the construction industry. The results for Nicaragua's tourism-driven economy have been significant, with the nation welcoming one million tourists in a calendar year for the first time in its history in 2010.[67]

Transport

Roads

The Inter-American Highway is the Central American section of the Pan-American Highway, and spans 5,470 kilometers (3,400 mi) between Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, and Panama City, Panama. Because of the 87-kilometer (54 mi) break in the highway known as the Darién Gap, it is not possible to cross between Central America and South America in an automobile.

Waterways

Ports and harbors

Airports

Railways

Education

See also

Notes

References

- "Central America Population". World Population Review. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- "Central America". central-america.org. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

Central America is located between North and South America and consists of multiple countries. Central America is not a continent but a subcontinent since it lies within the continent America. It borders on the northwest to the Pacific Ocean and in the northeast to the Caribbean Sea. The countries that belong to the subcontinent of Central America are El Salvador, Costa Rica, Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Mexico and Panama.

- "Spain accepts Mexican independence". HISTORY. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- Ribeiro, Pedro Freire (1995). Raízes do pensamento político da América Espanhola, 1780–1826. Niterói, RJ: Editora da Universidade Federal Fluminense. ISBN 85-228-0146-0. OCLC 35578070.

- "A Guide to the United States'History of Recognition, Diplomatic, and Consumer Relations, by Country, since 1776: Belize". Office of The Historian. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- Demographic Diversity and Change in the Central American Isthmus. Pebley, Anne R. and Luis Rosero-Bixby, eds., Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 1997. Also available in print form.

- América Insular ¿Qué es? ¿Cómo se divide? ¿Qué países pertenecen? (in Spanish)

- United Nations Statistics Division (2017). "Standard country or area codes for statistical use (M49)". New York City: United Nations Statistics Division. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- Augelli, JP (1962). "The Rimland-Mainland concept of culture areas in Middle America". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 52 (2): 119–29. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1962.tb00400.x. JSTOR 2561309.

- Hoopes, John W. and Oscar Fonseca Z. (2003). Goldwork and Chibchan Identity:Endogenous Change and Diffuse Unity in the Isthmo-Colombian Area (PDF). Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 978-0-8263-1000-2. Archived from the original (Online text reproduction) on 25 February 2009.

- Jones, Grant D. (1998). The Conquest of the Last Maya Kingdom. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. xix. ISBN 978-0804735223. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- Livingstone, Grace (2013). America's Backyard: The United States and Latin America from the Monroe Doctrine to the War on Terror. Zed Books Ltd. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-84813-611-3.

- Argueta, O; Huhn, S; Kurtenbach, S; Peetz, P (2011). "Blocked democracies in Central America" (PDF). GIGA Focus International Edition (5): 1–8. ISSN 1862-3581. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2013. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- "Extreme poverty increases in Nicaragua in 2013, study finds". American Free Press. 13 November 2014. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- "Central America". Merriam-Webster's collegiate dictionary. Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- IBP, Inc. (2015). Central American Countries Mineral Industry Handbook Volume 1 Strategic Information and Regulations. Lulu.com. pp. 7, 8. ISBN 978-1-329-09114-6.

- Taylor, MA; Alfaro, EJ (2005). "Central America and the Caribbean, Climate of". In Oliver, JE (ed.). Encyclopedia of world climatology. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series (1st ed.). New York: Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 183–9. doi:10.1007/1-4020-3266-8_37. ISBN 978-1-4020-3264-6.

- "Central America" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Butler, RA (2006). "Belize forest information and data". Tropical rainforests: deforestation rates tables and charts. Menlo Park, California: Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Butler, RA (2006). "Costa Rica forest information and data". Tropical rainforests: deforestation rates tables and charts. Menlo Park, California: Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Butler, RA (2006). "El Salvador forest information and data". Tropical rainforests: deforestation rates tables and charts. Menlo Park, California: Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Butler, RA (2006). "Guatemala forest information and data". Tropical rainforests: deforestation rates tables and charts. Menlo Park, California: Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Butler, RA (2006). "Honduras forest information and data". Tropical rainforests: deforestation rates tables and charts. Menlo Park, California: Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Butler, RA (2006). "Nicaragua forest information and data". Tropical rainforests: deforestation rates tables and charts. Menlo Park, California: Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Butler, RA (2006). "Panama forest information and data". Tropical rainforests: deforestation rates tables and charts. Menlo Park, California: Mongabay.com. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Harvey, CA; Komar, O; Chazdon, R; Ferguson, BG (2008). "Integrating agricultural landscapes with biodiversity conservation in the Mesoamerican hotspot". Conservation Biology. 22 (1): 8–15. doi:10.1111/j.1523-1739.2007.00863.x. PMID 18254848.

- Ramos, A (2 July 2010). "Belize protected areas 26% – not 40-odd percent". Amandala. Belize City. Archived from the original on 14 May 2011. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Belize Barrier Reef case study Archived 5 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Westminster.edu. Retrieved on 21 October 2011.

- Redo, DJ; Grau, HR; Aide, TM; Clark, ML (2012). "Asymmetric forest transition driven by the interaction of socioeconomic development and environmental heterogeneity in Central America". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (23): 8839–44. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8839R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201664109. PMC 3384153. PMID 22615408.

- "Central American pine-oak forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 4 November 2012.

- "Talamancan montane forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Central American montane forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- Astiz, L; Kanamori, H; Eissler, H (1987). "Source characteristics of earthquakes in the Michoacan seismic gap in Mexico" (PDF). Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 77 (4): 1326–46. Bibcode:1987BuSSA..77.1326A. doi:10.1785/BSSA0770041326. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 January 2015.

- White, RA (1985). "The Guatemala earthquake of 1816 on the Chixoy-Polochic fault". Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America. 75 (2): 455–73.

- "Life expectancy at birth, total". The World Bank Group. 29 June 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- "Life expectancy at birth, male". The World Bank Group. 29 June 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- "Life expectancy at birth, female". The World Bank Group. 29 June 2023. Retrieved 6 July 2023.

- "World Population Prospects 2022". population.un.org. United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX). population.un.org ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- IBP, Inc (2009). Central America Economic Integration and Cooperation Handbook Volume 1 Strategic Information, Organizations and Programs. Lulu.com. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-4387-4280-9.

- "2018 HDI Statistical Update". 14 September 2018. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 14 October 2018.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2019). "The world factbook". Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 1 June 2007.

- "Christianity in its Global Context" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2016.

- Holland, CL (November 2005). Ethnic and religious diversity in Central America: a historical perspective (PDF). 2005 Annual Meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. pp. 1–34. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Central American leaders agree on common currency". France 24. Retrieved 5 March 2018.

- British Embassy San Salvador (10 June 2013). "Extra-Regional Observer of Central American Integration System". Strengthening UK relationships with El Salvador. London: Government Digital Service. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Taiwan cuts ties with Costa Rica over recognition for China". The New York Times. 7 June 2007. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Ramzy, Austin (24 August 2018). "White House Criticizes China over el Salvador Recognition". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 January 2022.

- "Nicaragua cuts ties with Taiwan and pivots to China". the Guardian. 10 December 2021.

- International Monetary Fund (2012). "Report for selected countries and subjects". World economic outlook database, April 2012. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- International Monetary Fund (2012). "Gross domestic product based on purchasing-power-parity (PPP) valuation of country GDP". World economic outlook database, April 2012. Washington, D.C.: International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2014). "World exports by country". The world factbook. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Central Intelligence Agency (2014). "Export partners of Guatemala". The world factbook. Washington, D.C.: Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007.

- "Las "maquilas" no admiten sindicalistas | El Dipló". Archived from the original on 7 April 2011.

- International Monetary Fund (2014). World economic outlook October 2014: legacies, clouds, uncertainties (PDF). ISBN 978-1-4843-8066-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Data mostly refers to IMF staff estimates for the year 2013, made in April 2014. World Economic Outlook Database-April 2014, International Monetary Fund. Accessed on 9 April 2014.

- Data refers mostly to the year 2012. World Development Indicators database, World Bank. Database updated on 18 December 2013. Accessed on 18 December 2013.

- Cuellar, M (1 March 2013). "Foreign direct investments and tourism up". Channel 5 Belize. Belize: Great Belize Productions Ltd. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "2012: a remarkable year for Belize's tourism industry". The San Pedro Sun. San Pedro, Belize. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- "Belize | Tours & Activities – Project Expedition". Project Expedition. Retrieved 30 June 2016.

- Rodríguez, A (16 January 2014). "Costa Rica registró la llegada de más de 2,4 millones de turistas en 2013" [Costa Rica registered the arrival of more than 2.4 million tourists in 2013]. La Nación (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Rojas, JE (29 December 2004). "Turismo, principal motor de la economía durante el 2004" [Tourism, the principal engine of the economy in 2004]. La Nación (in Spanish). San José, Costa Rica. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- Inman, C (1997). "Impacts on developing countries of changing production and consumption patterns in developed countries: the case of ecotourism in Costa Rica" (PDF). Alajuela, Costa Rica: INCAE Business School. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 January 2010. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- Departamento de Estadísticas ICT (2006). "Anuário estadísticas de demanda 2006" (PDF) (in Spanish). Intituto Costarricense de Turismo. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- Jennifer Blanke and Thea Chiesa, ed. (2013). "Travel & tourism competitiveness report 2013" (PDF). World Economic Forum, Geneva, Switzerland. Retrieved 14 April 2013.

- Carroll, R (6 January 2007). "Ortega banks on tourism to beat poverty". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- "Nicaragua exceeds one mn foreign tourists for first time". Sify. Archived from the original on 17 October 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2019.

Further reading

- Berger, Mark T. Under northern eyes: Latin American studies and US hegemony in the Americas, 1898–1990. (Indiana UP, 1995).

- Biekart, Kees. "Assessing the 'arrival of Democracy' in Central America." (2014): 117–126. online

- Bowman, Kirk, Fabrice Lehoucq, and James Mahoney. "Measuring political democracy: Case expertise, data adequacy, and Central America." Comparative Political Studies 38.8 (2005): 939–970. online

- Craig, Kern William. "Public Policy in Central America: An Empirical Analysis." Public Administration Research 2.2 (2013): 105+ online.

- Dym, Jordana. From sovereign villages to national states: city, state, and federation in Central America, 1759–1839 (UNM Press, 2006).

- von Feigenblatt, Otto Federico. "Costa Rica's Neo-Realist Foreign Policy: Lifting the Veil Hiding the Discursive Co-Optation of Human Rights, Human Security, and Cosmopolitan Official Rhetoric." International Journal of Arts & Sciences Conference, (2009). online

- Krenn, Michael L. The Chains of Interdependence: US Policy Toward Central America, 1945–1954 (ME Sharpe, 1996).

- Kruijt, Dirk. Guerrillas: war and peace in Central America (2013).

- LaFeber, Walter. Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America (WW Norton & Company, 1993).

- Leonard, Thomas M. "Central America and the United States: Overlooked foreign policy objectives." The Americas (1993): 1–30 online.

- Oliva, Karen, and Chad Rector. "Unbalanced Regional Political Integration Is Unstable: Evidence from the Federal Republic of Central America (1823–1838)." Available at SSRN 2429123 (2014) online.

- Pearcy, Thomas L. We answer only to God: Politics and the Military in Panama, 1903–1947 (University of New Mexico Press, 1998).

- Pérez, Orlando J. Historical Dictionary of El Salvador (Rowman & Littlefield, 2016).

- Perez-Brignoli, Hector. A brief history of Central America (Univ of California Press, 1989).

- Sola, Mauricio. U.S. Intervention and Regime Change in Nicaragua (U of Nebraska Press, 2005).

- Topik, Steven C., and Allen Wells, eds. The second conquest of Latin America: coffee, henequen, and oil during the export boom, 1850–1930 (U of Texas Press, 2010).

External links

- American Heritage Dictionaries, Central America (archived 14 March 2007)

- Central America. Columbia Gazetteer of the World Online. 2006. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Hernández, Consuelo (2009). Reconstruyendo a Centroamérica a través de la poesía. Voces y perspectivas en la poesia latinoamericana del siglo XX. Madrid: Visor.

.jpg.webp)