Itasca State Park

Itasca State Park (pronounced eye-ta-ska) is a state park of Minnesota, United States, and contains the headwaters of the Mississippi River. The park spans 32,690 acres (132.3 km2) of northern Minnesota, and is located about 21 miles (34 km) north of Park Rapids, Minnesota and 25 miles (40 km) from Bagley, Minnesota. The park is part of Minnesota's Pine Moraines and Outwash Plains Ecological Subsection and is contained within Clearwater, Hubbard, and Becker counties.[2]

| Itasca State Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category IV (habitat/species management area) | |

The headwaters of the Mississippi River in Itasca State Park | |

Location of Itasca State Park in Minnesota  Itasca State Park (the United States) | |

| Location | Minnesota, United States |

| Coordinates | 47°14′23″N 95°12′27″W |

| Area | 32,690 acres (132.3 km2) |

| Elevation | 1,558 ft (475 m)[1] |

| Established | 1891 |

| Governing body | Minnesota Department of Natural Resources |

Itasca State Park was established by the Minnesota Legislature on April 20, 1891, making it the first of Minnesota's state parks and second oldest in the United States, behind Niagara Falls State Park. Henry Schoolcraft determined Lake Itasca as the river's source in 1832. It was named as a National Natural Landmark in 1965, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. About 500,000 people visit Itasca State Park annually.

History

Approximately 7–8,000 years ago, Native American hunters pursued wild animals for food in the Itasca State Park region. These early people ambushed bison, deer, and moose at watering sites and killed them with stone–tipped spears.[3] The bison kill site along Wilderness Drive in the park gives visitors historical insight about this period.

A few thousand years later, a group of people of the Woodland Period arrived at Lake Itasca. They lived in larger, more permanent settlements and made a variety of stone, wood, and bone tools. Burial mounds from this era can be seen today at the Itasca Indian Cemetery.

In 1832 Anishinaabe guide Ozawindib led explorer Henry Schoolcraft to the source of the Mississippi River at Lake Itasca. It was on this journey that Schoolcraft, with the help of an educated missionary companion, created the name Itasca from the Latin words for "truth" and "head" (veritas caput).[4] In the late 19th century, Jacob V. Brower, historian, anthropologist and land surveyor, came to the park region to settle the dispute of the actual location of the Mississippi's headwaters. Brower saw this region being quickly transformed by logging, and was determined to protect some of the pine forests for future generations. It was Brower's tireless efforts to save the remaining pine forest surrounding Lake Itasca that led the state legislature to establish Itasca as a Minnesota State Park on April 20, 1891, by a margin of only one vote.[3] Through his conservation work and the continuing efforts of others throughout the decades, the grounds of Itasca had been maintained.

Established in 1909, Itasca Biological Station and Labs (IBSL) is one of the oldest and largest continuously operated inland field training centers in the United States.[5] This site serves as a research facility and a site for summer-session undergraduate field biology courses for the University of Minnesota College of Biological Sciences. Each year new College of Biological Sciences students attend the "Nature of Life" orientation program which is held by the lake, allowing the study of a diverse, undisturbed environment from the organismal level to that of an entire ecosystem.[6]

Landscape

Lake Itasca, the official source of the Mississippi River and a scenic area of northern Minnesota, has remained relatively unchanged from its natural state. Most of the area has a heavy growth of timber that includes virgin red pine, which is also Minnesota's state tree. Some of the red pine in Itasca are over 200 years old.[7]

The Itasca terrain is sometimes referred to as "knob and kettle."[3] The knobs are mounds of debris deposited directly by the ice near the edge of glaciers or by melt–water streams flowing on or under the glacier's surface. The kettles are depressions, usually filled with water, formed by dormant ice masses buried or partially buried under glacial debris that later melted. The retreat of the ice around 10,000 years ago left behind 157 lakes of varying size that cover 3,000 acres (12 km2) of Itasca State Park. The glaciers deposited a moraine, a combination of silt, clay, sand, and gravel that covers the landscape to a depth of around 680 feet (210 m).[8] The park also integrates 27,500 acres (111 km2) of upland and 1,500 acres (6.1 km2) of swamp.

Biology and ecology

Plant life

The Itasca area's old-growth pine forests are almost as famous as the Mississippi headwaters. The area is currently one of the few places in state that has preserved these ancient pines from destruction. These pine forests were the main concern of Brower when he pushed to preserve the area as a state park. Logging operations in the late 19th and early 20th centuries depleted the large pine forests found in the park. Logging ended around 1920.[9]

Pine restoration has been attempted dating back to 1902, but with limited success.[2] Fire suppression in the area has eliminated wildfires in the park since the 1920s. Fire is necessary to the regeneration of white, red, and jack pines in the area because it opens the forest floor and canopy for new trees to grow. An overpopulation of white-tailed deer also stunt the regeneration efforts of these pines, as deer browse young pine seedling and prevent them from maturing into trees.[9]

A combination of jack pine and northern pin oak dominated the park before European settlement. Among the numerous varieties of trees Itasca accommodates are quaking aspen, bigtooth aspen, paper birch, red pine, white pine, as well as a mix of northern hardwoods. Current vegetation of the park now include: eastern white pine, red pine, aspen–birch, mixed hardwoods, jack pine barrens, and conifer bog. Logged areas of white and red pine are now home to a combination of aspen and birch trees, with aspen being the most dominant species of tree in the park today. The four principal forest communities in this locale remain to be aspen–birch, red pine, white pine, and northern hardwoods.[9]

The park is home to fourteen plants placed on the state endangered species list; these consist of ram's–head lady's slipper (Cypripedium arietinum), olivaceous spike–rush (Eleocharis olivacea), bog adder's–mouth (Malaxis paludosa), slender naiad (Najas gracillma), and sheathed pondweed (Potamogeton vaginatus).[4]

Fauna

Three terrestrial biomes, coniferous forest, deciduous forest, and prairie all intersect in the Itasca region and allow habitat for numerous vegetation and animals.[2] Itasca is home to over 200 bird species encompassing: bald eagles, loons, grebes, cormorants, herons, ducks, owls, hummingbirds, woodpeckers, chickadees, nuthatches, kinglets, vireos, tanagers, finches, and warblers. Residing among the many trails in the park are over 60 types of mammals including beaver, porcupine, black bear, and timber wolves.[9]

The white-tailed deer overpopulation has caused problems within the park. According to 1998 statistics it was estimated that the density of deer is around 15 to 17 per square mile compared with the 4–10 per square mile in similar areas in Wisconsin. The cause of the deer boom was the addition of man-made open spaces and a deer protection zone put in place from the early 20th century until the 1940s. Annual deer hunts have been held since 1940 in an effort to curb white tail deer population.[9]

The caddisfly Chilostigma itascae is only known to live in Nicollet Creek in the park.[10]

National Natural Landmark designation

Under the name of Itasca Natural Area, the area was designated a National Natural Landmark by the National Park Service under the Historic Sites Act.[11] It received this designation in November 1965 from the United States Secretary of the Interior, giving it recognition as an outstanding example of the nation's natural history.[12] The designation describes its significance:

The area contains some of the finest remaining stands of virgin red pine, spruce-balsam fir, and maple-basswood-aspen forest, supporting 141 bird and 53 mammal species, including bald eagles. [11]

Climate

Itasca State Park lies in northern Minnesota; a location that can be affected by three major air masses. An Arctic air stream extends south from Canada during the winter months; Pacific air that follows strong west winds move over the area and during the summer month a tropical air stream flows north from the Gulf of Mexico. These various air masses have a strong effect on the climate of the area around Itasca State Park.[9]

The winter climate produces extremely cold temperatures, with an average minimum temperature for Itasca being −4 °F (−20 °C).[13] This cold weather is accompanied with snowfall amounts averaging around 54.6 inches (139 cm) annually. A combination of the Arctic air with heavy snowfall and wind can create severe blizzard conditions in the area.[9]

In the summer, the Pacific and tropical winds from the Gulf create warm to hot temperatures, with the highs during July averaging 78.4 °F (25.8 °C).[13] However a clash of cool, dry polar air from Canada and the moisture from the southern tropical Gulf air can lead to showers and thunderstorms. The average annual rainfall in the Itasca area is 27 inches (69 cm).[13] It has a relatively short growing season, with the first frost usually occurring in late September to early October and the first frost-free days not occurring until mid-May or early June.[9]

| Climate data for Itasca State Park (1991–2020 normals, extremes 1911–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 62 (17) |

63 (17) |

81 (27) |

96 (36) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

105 (41) |

101 (38) |

99 (37) |

92 (33) |

74 (23) |

59 (15) |

105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 16.9 (−8.4) |

22.8 (−5.1) |

35.9 (2.2) |

51.0 (10.6) |

65.0 (18.3) |

74.3 (23.5) |

78.8 (26.0) |

77.4 (25.2) |

68.1 (20.1) |

52.1 (11.2) |

34.8 (1.6) |

22.2 (−5.4) |

49.9 (9.9) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 6.3 (−14.3) |

10.6 (−11.9) |

24.0 (−4.4) |

38.5 (3.6) |

52.2 (11.2) |

62.4 (16.9) |

66.9 (19.4) |

65.1 (18.4) |

56.2 (13.4) |

42.3 (5.7) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

13.7 (−10.2) |

38.7 (3.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | −4.3 (−20.2) |

−1.6 (−18.7) |

12.1 (−11.1) |

26.0 (−3.3) |

39.4 (4.1) |

50.6 (10.3) |

54.9 (12.7) |

52.7 (11.5) |

44.3 (6.8) |

32.5 (0.3) |

18.6 (−7.4) |

5.1 (−14.9) |

27.5 (−2.5) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −51 (−46) |

−52 (−47) |

−44 (−42) |

−17 (−27) |

11 (−12) |

24 (−4) |

32 (0) |

26 (−3) |

16 (−9) |

−14 (−26) |

−30 (−34) |

−47 (−44) |

−52 (−47) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 0.75 (19) |

0.72 (18) |

1.22 (31) |

2.00 (51) |

3.18 (81) |

4.57 (116) |

3.53 (90) |

3.23 (82) |

3.08 (78) |

2.85 (72) |

1.32 (34) |

1.12 (28) |

27.57 (700) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 9.6 (24) |

8.0 (20) |

7.8 (20) |

6.2 (16) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

1.0 (2.5) |

9.1 (23) |

9.8 (25) |

51.6 (131) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 8.8 | 7.6 | 7.5 | 8.8 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 12.8 | 10.9 | 11.9 | 11.3 | 8.8 | 10.0 | 125.6 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.5 | 5.9 | 3.9 | 1.9 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 4.1 | 8.2 | 31.6 |

| Source: NOAA[14][15] | |||||||||||||

Recreation

Itasca State Park's recreational activities cover all four seasons of the year. Within the restored log building headquarters is a 31-bed youth hostel operated by Hostelling International USA, open to travelers of all ages.[16]

Spring reels in the fishermen for the May fishing openers of walleye, northern pike, bass, and panfish. The park is in full bloom including a vast array of wildflowers. Birding is also a popular spring activity as the varying species return from migration.

Lake Itasca is a popular location for summer activities in Minnesota, with 496,651 visitors in 2006.[4] Fishing, canoeing, boating, and kayaking equipment are always accessible. On land recreation consists of biking via the Heartland Trail, horseback riding, and hiking. A 9.6-mile (15.4 km) section of the North Country National Scenic Trail passes through the park's southern tier and includes three backcountry campsites. Numerous historical sites are available to view. The headwaters of the Mississippi River are one of the most visited sites featured at the park. Tourists can visit the new Mary Gibbs Visitor Center and the exhibits at the Jacob V. Brower Visitor Center. The park also offers a 100-foot (30 m) climb up the historic Aiton Heights Fire Tower.

Fall unveils the beautiful array of colors amidst the variety of trees throughout the park. This is another recommended season to bike, hike, or even take a leisurely walk through the designated trails. The park offers 33 miles (53 km) worth of hiking trails.[9]

Winter lures in the ice fishermen, who gather on Lake Itasca. Snowmobilers can travel hundreds of miles of groomed snowmobile trails, while the skiers use 30 miles (48 km) of cross country skiing trails (both novice and skilled level) that are maintained regularly.

Park facilities

Scattered around the boundaries of Itasca State Park stand a variety of historical and tourist attractions. Constructed over a 37-year period from 1905 to 1942, development was undertaken by two Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) camps as well as two Works Progress Administration (WPA) camps. Architects for this later development were from the Minnesota Central Design Office of the National Park Service with Edward W. Barber and V.C. Martin serving as principal architects for the park buildings.[7] Log construction was generally used because timber was easily available in the area.

Rustic style design

Itasca's rustic style design is the largest collection of log–constructed buildings in the state park system. It provides a uniform appearance to the park, setting it apart from all others. Douglas Lodge, built in 1905, is the oldest surviving building and the first to be constructed in the Rustic Style.[17] This structure is located along the south shore of Lake Itasca and was built using peeled logs harvested from the surrounding forests. Funded by State legislature in 1903, it became the first building to house the park's visitors. Originally, it was called "Itasca Park Lodge" or "State House", but was later named after Minnesota Attorney General Wallace B. Douglas, a prominent figure in the battle to save the timber in Itasca State Park at the start of the 20th century.[17] At the time, very few governments were setting aside land for conservation, which shows the significance of this encounter. Douglas Lodge has provided tourist facilities since 1911 and remains functional today after undergoing renovations in the years following its grand opening. The Lodge is used as a hotel for guests to stay in, and the main lobby for the "Douglas Lodge Cabins" around it. There is also a restaurant famous for wild rice soup.

The Clubhouse, assembled in 1911, overlooks Lake Itasca. The interior contains ten dormitories placed around a two–story Rustic Style lobby. The Clubhouse contains a very large fireplace, couches, and a very great staircase. Over the years, the Clubhouse encountered few problems in the maintenance department other than minor deterioration in the lower logs, which were replaced in 1984. Today, guests may stay in the ten rooms.

The Old Timer's Cabin is also found on the shores of Lake Itasca, located north of the Clubhouse. This was the first CCC–constructed building to appear in the park. The CCC originally referred to the Old Timer's Cabin as the "Honeymooner's Cabin" because of its small size and relative isolation .[17]

Forest Inn is one of the largest creations by the CCC in the state park system, standing 144 by 50 feet (44 by 15 m). It took a crew of 200 CCC members to produce the finished product, complete with both split stone and log components. The stone used in the walkways were scrap pieces from the quarries and stone works of the St. Cloud area and the logs used on the cabin came from the pine and balsam fir within the park vicinity.[17]

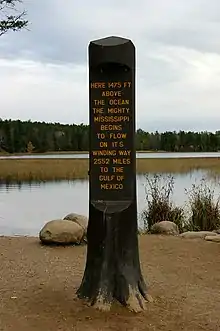

Mississippi headwaters

The headwaters of the Mississippi River are clearly defined by a 44-foot-long (13 m) long outlet dam at the north end of Lake Itasca.[17] This setup allows tourists to wade in shallow water or cross over it by way of the bridge constructed of logs. In 1903 a 24-year-old park commissioner named Mary Gibbs played a significant role in saving the tall pine forests and shoreline of the Mississippi River Headwaters by resisting efforts to log the area. In honor of her efforts, the Mary Gibbs Visitor Center, which encloses a restaurant, gift shop, various displays and exhibits of the park's features, and an outdoor plaza now exists. Visitors can walk across the rocks connecting the sides of the Mississippi. There is also a bridge, for those who don't want to get wet.

Archaeological and cemetery sites

Itasca State Park currently contains more than 30 known archaeological and cemetery sites. The study of archaeological remains in the Itasca area was started by Jacob V. Brower in the late 19th century. Survey work on archaeological remains place human activity in the Itasca area as early as 8,000 years ago. Human activity spans over several historical periods, from Early Eastern Archaic, through the Archaic and Woodland periods.[9]

The Itasca Bison Kill Site is the oldest archaeological site within Itasca State Park. The site dates back to the Early Eastern Archaic period. The discovery took place in 1937 during the construction of the Wilderness Drive. It is located near the southwestern shore of Lake Itasca by Nicollet Creek. An initial finding of the remains of human made artifacts prompted the University of Minnesota to conduct an extensive excavation of the area in 1964 and 1965. Excavation of the area revealed a large of amount of bones from an extinct species of Bison hence the name of the site. Human tools, such as knives, spears and scrapers were discovered in the vicinity.[9]

The Itasca State Park Site was discovered and excavated by Jacob Brower in the late 19th century. The site consists of ten burial mounds, dating back approximately 800 years, along the northeastern shore of Lake Itasca. An effort was made in the late 1980s to rebury American Indian remains that had been removed. This act was in collaboration with a statewide effort to rebury the several thousand remains that had been excavated.[9]

Several other major sites exist in Itasca, including the Headwaters Site, which is located along the northeast shore of Lake Itasca, and a village site discovered by Jacob Brower in the late 19th century. Significant portions of this site have been converted into trails, parking lots and visitor service facilities. Archaeological remains have also been discovered at the Headwater's West Terrace Site along the west bank of the Mississippi near Lake Itasca, the Bear Paw Campground Site which lies adjacent to Lake Itasca, as well as Pioneer Cemetery which is located on the eastern shore of Lake Itasca and contains the remains of early European pioneers.[9]

Footnotes

- "Itasca State Park". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. January 11, 1980. Retrieved February 25, 2011.

- Snow, Kristin. Management of Pine Regeneration in Itasca State Park. Minnesota, 1999.

- Itasca State Park, Visit Bemidji, http://www.visitbemidji.com/itasca_state_park.html Archived June 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Itasca. 2007. 22 April 2007 <http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/itasca/narrative.html Archived 2013-06-28 at the Wayback Machine>

- The Wildest Classroom in Minnesota, Itasca Biological Station and Laboratories, http://cbs.umn.edu/itasca/.

- "Itasca Biological Station and Laboratories | College of Biological Sciences". Archived from the original on April 10, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- Itasca State Park, Minnesota Historical Society, http://www.mnhs.org/places/nationalregister/stateparks/Itasca.html.

- Anita Cholewa and David Biesboer, Common Plants of Itasca State Park, Minnesota: Bell Museum of Natural History,2005

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Itasca State Park Management Plan. Minnesota, 1998.

- Henderson, Carrol L. (January–February 2008). "Minnesota Profile: Headwaters Chilostigman Caddisfly". Minnesota Conservation Volunteer. 71 (416): 72–73. Archived from the original on March 25, 2009.

- "Itasca Natural Area". NNL Guide-Minnesota. National Park Service. Retrieved September 15, 2012.

- "Overview, National Natural Landmarks". Nature & Science. National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 21, 2008. Retrieved September 26, 2008.

- "Climatography of the United States". National Climatic Data Center. 1971–2000. Retrieved May 3, 2007.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- "Station: Itasca UNIV of MINN, MN". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved June 23, 2021.

- "Youth Hostel Lake Itasca Minnesota Budget Backpacker Cheap Hotel". www.hiusa.org. Archived from the original on June 17, 2010.

- Itasca State Park, Minnesota Historical Society, http://www.mnhs.org/places/nationalregister/stateparks/ItascaRes.html.

References

- Cholewa, Anita and David Biesboer. Common Plants of Itasca State Park. Minnesota: Bell Museum of Natural History, 2005

- Itasca. 2007. Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. 18 April 2007.

- Itasca State Park. 2001. Minnesota Historical Society. 19 April 2007. <http://www.mnhs.org/places/nationalregister/stateparks/Itasca.html>

- Itasca State Park. 2004. Visit Bemidji. 18 April 2007 <http://www.visitbemidji.com/itasca_state_park.html Archived June 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine>.

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, Itasca. 2007. 22 April 2007 <https://web.archive.org/web/20130628172241/http://www.dnr.state.mn.us/state_parks/itasca/narrative.html

- Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. Itasca State Park Management Plan. Minnesota, 1998.

- Snow, Kristin. Management of Pine Regeneration in Itasca State Park. Minnesota, 1999.

- "The Wildest Classroom in Minnesota." Itasca Biological Station and Laboratories. 26 March 2007. Regents of the University of Minnesota. 7 May 2007.<http://cbs.umn.edu/itasca/>.

- Welcome to Itasca Lakes Country. Itasca Area Lakes Tourism Association. 19 April 2007. <http://www.itascaarea.com/>