Jamaican Patois

Jamaican Patois (/ˈpætwɑː/; locally rendered Patwah and called Jamaican Creole by linguists) is an English-based creole language with West African, Taino, Irish, Spanish, Hindi, Portuguese, Chinese and German influences, spoken primarily in Jamaica and among the Jamaican diaspora. Words or slang from Jamaican Patois will be heard in other Caribbean countries, the United Kingdom and Toronto, Canada.[5] The majority of non-English words in Patois derived from the West African Akan language.[5] It is spoken by the majority of Jamaicans as a native language.

| Jamaican Patois | |

|---|---|

| Patwa, Jamiekan / Jamiekan Kriyuol,[1] Jumiekan / Jumiekan Kryuol / Jumieka Taak / Jumieka taak / Jumiekan languij[2][3] | |

| Native to | Jamaica |

Native speakers | 3.2 million (2000–2001)[4] |

English creole

| |

| Dialects | |

| Official status | |

| Regulated by | not regulated |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | jam |

| Glottolog | jama1262 |

| Linguasphere | 52-ABB-am |

Patois developed in the 17th century when enslaved people from West and Central Africa were exposed to, learned, and nativized the vernacular and dialectal forms of English spoken by the slaveholders: British English, Scots, and Hiberno-English. Jamaican Creole exhibits a gradation between more conservative creole forms that are not significantly mutually intelligible with English,[6] and forms virtually identical to Standard English.[7]

Jamaicans refer to their language as Patois, a term also used as a lower-case noun as a catch-all description of pidgins, creoles, dialects, and vernaculars worldwide. Creoles, including Jamaican Patois, are often stigmatized as low-prestige languages even when spoken as the mother tongue by the majority of the local population.[8] Jamaican pronunciation and vocabulary are significantly different from English despite heavy use of English words or derivatives.[9]

Significant Jamaican Patois-speaking communities exist among Jamaican expatriates and non Jamaican [7]in South Florida, New York City, Toronto, Hartford, Washington, D.C., Nicaragua, Costa Rica, the Cayman Islands,[10] and Panama, as well as London,[11] Birmingham, Manchester, and Nottingham. The Cayman Islands in particular have a very large Jamaican Patois-speaking community, with 16.4% of the population conversing in the language.[12] A mutually intelligible variety is found in San Andrés y Providencia Islands, Colombia, brought to the island by descendants of Jamaican Maroons (escaped slaves) in the 18th century. Mesolectal forms are similar to very basilectal Belizean Kriol.

Jamaican Patois exists mainly as a spoken language and is also heavily used for musical purposes, especially in reggae and dancehall as well as other genres. Although standard British English is used for most writing in Jamaica, Jamaican Patois has gained ground as a literary language for almost a hundred years. Claude McKay published his book of Jamaican poems Songs of Jamaica in 1912. Patois and English are frequently used for stylistic contrast (codeswitching) in new forms of Internet writing.[13]

Phonology

Accounts of basilectal Jamaican Patois (that is, its most divergent rural varieties) suggest around 21 phonemic consonants[14] with an additional phoneme (/h/) in the Western dialect.[15] There are between nine and sixteen vowels.[16] Some vowels are capable of nasalization and others can be lengthened.[15]

| Labial | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal2 | Velar | Glottal | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | ||||||||

| Stop | p | b | t | d | tʃ | dʒ | c | ɟ | k | ɡ | ||

| Fricative | f | v | s | z | ʃ | (h)1 | ||||||

| Approximant /Lateral |

ɹ | j | w | |||||||||

| l | ||||||||||||

- ^1 The status of /h/ as a phoneme is dialectal: in western varieties, it is a full phoneme and there are minimal pairs (/hiit/ 'hit' and /iit/ 'eat'); in central and eastern varieties, vowel-initial words take an initial [h] after vowel-final words, preventing the two vowels from falling together, so that the words for 'hand' and 'and' (both underlyingly /an/) may be pronounced [han] or [an].[18]

- ^2 The palatal stops [c], [ɟ][note 1] and [ɲ] are considered phonemic by some accounts[19] and phonetic by others.[20] For the latter interpretation, their appearance is included in the larger phenomenon of phonetic palatalization.

Examples of palatalization include:[21]

- /kiuu/ → [ciuː] → [cuː] ('a quarter quart (of rum)')

- /ɡiaad/ → [ɟiaːd] → [ɟaːd] ('guard')

- /piaa + piaa/ → [pʲiãːpʲiãː] → [pʲãːpʲãː] ('weak')

Voiced stops are implosive whenever in the onset of prominent syllables (especially word-initially) so that /biit/ ('beat') is pronounced [ɓiːt] and /ɡuud/ ('good') as [ɠuːd].[14]

Before a syllabic /l/, the contrast between alveolar and velar consonants has been historically neutralized with alveolar consonants becoming velar so that the word for 'bottle' is /bakl̩/ and the word for 'idle' is /aiɡl̩/.[22]

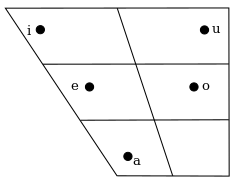

Jamaican Patois exhibits two types of vowel harmony; peripheral vowel harmony, wherein only sequences of peripheral vowels (that is, /i/, /u/, and /a/) can occur within a syllable; and back harmony, wherein /i/ and /u/ cannot occur within a syllable together (that is, /uu/ and /ii/ are allowed but * /ui/ and * /iu/ are not).[23] These two phenomena account for three long vowels and four diphthongs:[24]

| Vowel | Example | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| /ii/ | /biini/ | 'tiny' |

| /aa/ | /baaba/ | 'barber' |

| /uu/ | /buut/ | 'booth' |

| /ia/ | /biak/ | 'bake' |

| /ai/ | /baik/ | 'bike' |

| /ua/ | /buat/ | 'boat' |

| /au/ | /taun/ | 'town' |

Sociolinguistic variation

Jamaican Patois features a creole continuum (or a linguistic continuum):[25][26][27] the variety of the language closest to the lexifier language (the acrolect) cannot be distinguished systematically from intermediate varieties (collectively referred to as the mesolect) or even from the most divergent rural varieties (collectively referred to as the basilect).[28] This situation came about with contact between speakers of a number of Niger–Congo languages and various dialects of English, the latter of which were all perceived as prestigious and the use of which carried socio-economic benefits.[29] The span of a speaker's command of the continuum generally corresponds to social context.[30]

Grammar

The tense/aspect system of Jamaican Patois is fundamentally unlike that of English. There are no morphologically marked past participles; instead, two different participle words exist: en and a. These are not verbs, but rather invariant particles that cannot stand alone (like the English to be). Their function also differs from those of English.

According to Bailey (1966), the progressive category is marked by /a~da~de/. Alleyne (1980) claims that /a~da/ marks the progressive and that the habitual aspect is unmarked but by its accompaniment with words such as "always", "usually", etc. (i.e. is absent as a grammatical category). Mufwene (1984) and Gibson and Levy (1984) propose a past-only habitual category marked by /juusta/ as in /weɹ wi juusta liv iz not az kual az iiɹ/ ('where we used to live is not as cold as here').[31]

For the present tense, an uninflected verb combining with an iterative adverb marks habitual meaning as in /tam aawez nua wen kieti tel pan im/ ('Tom always knows when Katy tells/has told about him').[32]

- en is a tense indicator

- a is an aspect marker

- (a) go is used to indicate the future

- Mi run (/mi ɹon/)

- I run (habitually); I ran

- Mi a run or Mi de run, (/mi a ɹon/ or /mi de ɹon/)

- I am running

- A run mi did a run, (/a ɹon mi dida ɹon/ or /a ɹon mi ben(w)en a ɹon/)

- I was running

- Mi did run (/mi did ɹon/ or /mi ben(w)en ɹon/)

- I have run; I had run

- Mi a go run (/mi a ɡo ɹon/)

- I am going to run; I will go on a run

As in other Caribbean Creoles (that is, Guyanese Creole and San Andrés-Providencia Creole; Sranan Tongo is excluded) /fi/ has a number of functions, including:[33]

- Directional, dative, or benefactive preposition

- Dem a fight fi wi (/dem a fait fi wi/) ('They are fighting for us')[34]

- Genitive preposition (that is, marker of possession)

- Dat a fi mi book (/dat a fi mi buk/) ('that's my book')

- Modal auxiliary expressing obligation or futurity

- Him fi kom up ya (/im fi kom op ja/) ('he ought to come up here')

- Pre-infinitive complementizer

Pronominal system

The pronominal system of Standard English has a four-way distinction of person, number, gender and case. Some varieties of Jamaican Patois do not have the gender or case distinction, but all varieties distinguish between the second person singular and plural (you).[36]

- I, me = /mi/

- you, you (singular) = /ju/

- he, him = /im/ (pronounced [ĩ] in the basilect varieties)

- she, her = /ʃi/ or /im/ (no gender distinction in basilect varieties)

- we, us, our = /wi/

- you (plural) = /unu/

- they, them, their = /dem/

Copula

- the Jamaican Patois equative verb is also a

- e.g. /mi a di tiitʃa/ ('I am the teacher')

- Jamaican Patois has a separate locative verb deh

- e.g. /wi de a london/ or /wi de inna london/ ('we are in London')

- with true adjectives in Jamaican Patois, no copula is needed

- e.g. /mi haadbak nau/ ('I am old now')

This is akin to Spanish in that both have two distinct forms of the verb "to be" – ser and estar – in which ser is equative and estar is locative. Other languages, such as Portuguese and Italian, make a similar distinction. (See Romance Copula.)

Negation

- /no/ is used as a present tense negator:

- /if kau no did nua au im tɹuatual tan im udn tʃaans pieɹsiid/ ('If the cow knew that his throat wasn't capable of swallowing a pear seed, he wouldn't have swallowed it')[37]

- /kiaan/ is used in the same way as English can't

- /it a puaɹ tiŋ dat kiaan maʃ ant/ ('It is a poor thing that can't mash an ant')[38]

- /neva/ is a negative past participle.[39]

- /dʒan neva tiif di moni/ ('John did not steal the money')

Orthography

Patois has long been written with various respellings compared to English so that, for example, the word "there" might be written ⟨de⟩, ⟨deh⟩, or ⟨dere⟩, and the word "three" as ⟨tree⟩, ⟨tri⟩, or ⟨trii⟩. Standard English spelling is often used and a nonstandard spelling sometimes becomes widespread even though it is neither phonetic nor standard (e.g. ⟨pickney⟩ for /pikni/, 'child').

In 2002, the Jamaican Language Unit was set up at the University of the West Indies at Mona to begin standardizing the language, with the aim of supporting non-English-speaking Jamaicans according to their constitutional guarantees of equal rights, as services of the state are normally provided in English, which a significant portion of the population cannot speak fluently. The vast majority of such persons are speakers of Jamaican Patois. It was argued that failure to provide services of the state in a language in such general use or discriminatory treatment by officers of the state based on the inability of a citizen to use English violates the rights of citizens. The proposal was made that freedom from discrimination on the ground of language be inserted into the Charter of Rights.[40] They standardized the Jamaican alphabet as follows:[41]

| Letter | Patois | English |

|---|---|---|

| i | sik | sick |

| e | bel | bell |

| a | ban | band |

| o | kot | cut |

| u | kuk | cook |

| Letter | Patois | English |

|---|---|---|

| ii | tii | tea |

| aa | baal | ball |

| uu | shuut | shoot |

| Letter | Patois | English |

|---|---|---|

| ie | kiek | cake |

| uo | gruo | grow |

| ai | bait | bite |

| ou | kou | cow |

Nasal vowels are written with -hn, as in kyaahn (can't) and iihn (isn't it?)

| Letter | Patois | English |

|---|---|---|

| b | biek | bake |

| d | daag | dog |

| ch | choch | church |

| f | fuud | food |

| g | guot | goat |

| h | hen | hen |

| j | joj | judge |

| k | kait | kite |

| l | liin | lean |

| m | man | man |

| n | nais | nice |

| ng | sing | sing |

| p | piil | peel |

| r | ron | run |

| s | sik | sick |

| sh | shout | shout |

| t | tuu | two |

| v | vuot | vote |

| w | wail | wild |

| y | yong | young |

| z | zuu | zoo |

| zh | vorzhan | version |

h is written according to local pronunciation, so that hen (hen) and en (end) are distinguished in writing for speakers of western Jamaican, but not for those of central Jamaican.

Vocabulary

Jamaican Patois contains many loanwords, most of which are African in origin, primarily from Twi (a dialect of Akan).[42]

Many loanwords come from English, but some are also borrowed from Spanish, Portuguese, Hindi, Arawak and African languages, as well as Scottish and Irish dialects.

Examples from African languages include /se/ meaning that (in the sense of "he told me that..." = /im tel mi se/), taken from Ashanti Twi, and Duppy meaning ghost, taken from the Twi word dupon ('cotton tree root'), because of the African belief of malicious spirits originating in the roots of trees (in Jamaica and Ghana, particularly the cotton tree known in both places as "Odom").[43] The pronoun /unu/, used for the plural form of you, is taken from the Igbo language. Red eboe describes a fair-skinned black person because of the reported account of fair skin among the Igbo in the mid-1700s.[44] De meaning to be (at a location) comes from Yoruba.[45] From the Ashanti-Akan, comes the term Obeah which means witchcraft, from the Ashanti Twi word Ɔbayi which also means "witchcraft".[42]

Words from Hindi include ganja (marijuana).[46] Pickney or pickiney meaning child, taken from an earlier form (piccaninny) was ultimately borrowed from the Portuguese pequenino (the diminutive of pequeno, small) or Spanish pequeño ('small').[47]

There are many words referring to popular produce and food items—ackee, callaloo, guinep, bammy, roti, dal, kamranga. See Jamaican cuisine.

Jamaican Patois has its own rich variety of swearwords. One of the strongest is bloodclaat (along with related forms raasclaat, bomboclaat, pussyclaat and others—compare with bloody in Australian English and British English, which is also considered a profanity).[48]

Homosexual men may be referred to with the pejorative term /biips/,[49] fish [50] or battyboys.

Example phrases

- Mi almos lik 'im (/mi aalmuos lik im/) – I almost hit him[51]

- 'im kyaant biit mi, 'im jus lucky dat 'im won (/im caan biit mi, im dʒos loki dat im won/) – He can't beat me, he just got lucky that he won.[52]

- Seen /siin/ – Affirmative particle[53]

- /papiˈʃuo/ – Foolish exhibition, a person who makes a foolish exhibition of him or herself, or an exclamation of surprise.[54]

- /uman/ – Woman[55]

- /bwoi/ – Boy[56]

Literature and film

A rich body of literature has developed in Jamaican Patois. Notable among early authors and works are Thomas MacDermot's All Jamaica Library and Claude McKay's Songs of Jamaica (1909), and, more recently, dub poets Linton Kwesi Johnson and Mikey Smith. Subsequently, the life-work of Louise Bennett or Miss Lou (1919–2006) is particularly notable for her use of the rich colorful patois, despite being shunned by traditional literary groups. "The Jamaican Poetry League excluded her from its meetings, and editors failed to include her in anthologies."[57] Nonetheless, she argued forcefully for the recognition of Jamaican as a full language, with the same pedigree as the dialect from which Standard English had sprung:

Dah language weh yuh proud a,

Weh yuh honour an respec –

Po Mas Charlie, yuh no know se

Dat it spring from dialec!

— Bans a Killin

After the 1960s, the status of Jamaican Patois rose as a number of respected linguistic studies were published, by Frederic Cassidy (1961, 1967), Bailey (1966) and others.[58] Subsequently, it has gradually become mainstream to codemix or write complete pieces in Jamaican Patois; proponents include Kamau Brathwaite, who also analyses the position of Creole poetry in his History of the Voice: The Development of Nation Language in Anglophone Caribbean Poetry (1984). However, Standard English remains the more prestigious literary medium in Jamaican literature. Canadian-Caribbean science-fiction novelist Nalo Hopkinson often writes in Trinidadian and sometimes Jamaican Patois. Jean D'Costa penned a series of popular children's novels, including Sprat Morrison (1972; 1990), Escape to Last Man Peak (1976), and Voice in the Wind (1978), which draw liberally from Jamaican Patois for dialogue, while presenting narrative prose in Standard English.[59] Marlon James employs Patois in his novels including A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014). In his science fiction novel Kaya Abaniah and the Father of the Forest (2015), British-Trinidadian author Wayne Gerard Trotman presents dialogue in Trinidadian Creole, Jamaican Patois, and French while employing Standard English for narrative prose.

Jamaican Patois is also presented in some films and other media, for example, the character Tia Dalma's speech from Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man's Chest, and a few scenes in Meet Joe Black in which Brad Pitt's character converses with a Jamaican woman (Lois Kelly Miller). In addition, early Jamaican films like The Harder They Come (1972), Rockers (1978), and many of the films produced by Palm Pictures in the mid-1990s (e.g. Dancehall Queen and Third World Cop) have most of their dialogue in Jamaican Patois; some of these films have even been subtitled in English. It was also used in the second season of Marvel's Luke Cage but the accents were described as "awful" by Jamaican Americans.[60]

Bible

In December 2011, it was reported that the Bible was being translated into Jamaican Patois. The Gospel of Luke has already appeared as Jiizas: di Buk We Luuk Rait bout Im. While the Rev. Courtney Stewart, managing the translation as General Secretary of the West Indies Bible Society, believes this will help elevate the status of Jamaican Patois, others think that such a move would undermine efforts at promoting the use of English. The Patois New Testament was launched in Britain (where the Jamaican diaspora is significant) in October 2012 as "Di Jamiekan Nyuu Testiment", and with print and audio versions in Jamaica in December 2012.[61][62][63]

|

|

The system of spelling used in Di Jamiekan Nyuu Testiment is the phonetic Cassidy Writing system adopted by the Jamaica Language Unit of the University of the West Indies, and while most Jamaicans use the informal "Miss Lou" writing system, the Cassidy Writing system is an effort at standardizing Patois in its written form.[66]

Notes

- Also transcribed as [kʲ] and [ɡʲ].

References

Citations

- Di Jamiekan Nyuu Testiment – The Jamaican New Testament, published by: The Bible Society of the West Indies, 2012

- Chang, Larry. "Jumieka Languij: Aatagrafi / Jamaican Language: Orthography". LanguiJumieka.

Chang, Larry. "Jumieka Languij: Bout / Jamaican Language: About". LanguiJumieka. - Larry Chang: Biesik Jumiekan. Introduction to Jamaican Language, published by: Gnosophia Publishers, 2014.

- Jamaican Patois at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

- Cassidy, F. G. "Multiple etymologies in Jamaican Creole". Am Speech, 1966, 41:211–215.

- Brown-Blake 2008, p. 32.

- DeCamp (1961:82)

- Velupillai 2015, pp. 481.

- Brown-Blake 2008, p. ?.

- "What does it mean to be Jamaican in Cayman? | Loop Jamaica".

- Sebba, Mark (1993), London Jamaican, London: Longman.

- Labor force and employment eso.ky

- Hinrichs, Lars (2006), Codeswitching on the Web: English and Jamaican Creole in E-Mail Communication. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- Devonish & Harry (2004:456)

- Velupillai 2015, p. 483.

- Harry (2006:127)

- Harry (2006:126–127)

- Harry (2006:126)

- such as Cassidy & Le Page (1980:xxxix)

- such as Harry (2006)

- Devonish & Harry (2004:458)

- Cassidy (1971:40)

- Harry (2006:128–129)

- Harry (2006:128)

- Rickford (1987:?)

- Meade (2001:19)

- Patrick (1999:6)

- Irvine-Sobers GA (2018). The acrolect in Jamaica: The architecture of phonological variation (PDF). Studies in Caribbean Languages. Berlin: Language Science Press. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1306618. ISBN 978-3-96110-114-6.

- Irvine (2004:42)

- DeCamp (1977:29)

- Gibson (1988:199)

- Mufwene (1983:218) cited in Gibson (1988:200)

- Winford (1985:589)

- Bailey (1966:32)

- Patrick (1995:244)

- Patrick (2007:?)

- Lawton (1984:126) translates this as "If the cow didn't know that his throat was capable of swallowing a pear seed, he wouldn't have swallowed it."

- Lawton (1984:125)

- Irvine (2004:43–44)

- "The Jamaican Language Unit, The University of West Indies at Mona". Archived from the original on 2020-11-06. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- ""Handout: Spelling Jamaican the Jamaican way"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-09. Retrieved 2012-12-26.

- Williams, Joseph J. (1932). Voodoos and Obeahs:Phrases of West Indian Witchcraft. Library of Alexandria. p. 90. ISBN 1-4655-1695-6.

- Williams, Joseph J. (1934). Psychic Phenomena of Jamaica. The Dial Press. p. 156. ISBN 1-4655-1450-3.

- Cassidy, Frederic Gomes; Robert Brock Le Page (2002). A Dictionary of Jamaican English (2nd ed.). University of the West Indies Press. p. 168. ISBN 976-640-127-6. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- McWhorter, John H. (2000). The Missing Spanish Creoles: Recovering the Birth of Plantation Contact Languages. University of California Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-520-21999-6. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- "Ganja planta". Jamaican Patwah.

- "pickney". Lexico. May 14, 2022. Archived from the original on May 14, 2022. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- "Definitions of "Bloodclaat" (Vulgar)". Jamaican Patwah.

- Patrick (1995:234)

- "Fish | Patois Definition on Jamaican Patwah".

- Patrick (1995:248)

- Hancock (1985:237)

- Patrick (1995:253)

- Hancock (1985:190)

- Cassidy & Le Page (1980:lxii)

- Devonish & Harry (2004:467)

- Ramazani, Ellmann & O'Clair (2003:15)

- Alison Donnell, Sarah Lawson Welsh (eds), The Routledge Reader in Caribbean Literature, Routledge, 2003, Introduction, p. 9.

- Bridget Jones (1994). "Duppies and other Revenants: with particular reference to the use of the supernatural in Jean D'Costa's work". In Vera Mihailovich-Dickman (ed.). "Return" in Post-colonial Writing: A Cultural Labyrinth. Rodopi. pp. 23–32. ISBN 9051836481.

- Domise, Andray (27 June 2018). "Luke Cage's Portrayal of Jamaicans was Atrocious". Vice. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

- Pigott, Robert (25 December 2011). "Jamaica's patois Bible: The word of God in creole". BBC News. Retrieved 28 September 2018.

- "Jamaican patois Bible released "Nyuu Testiment"". Colorado Springs Gazette. The Associated Press. 8 December 2012. Archived from the original on December 11, 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

For patois expert Hubert Devonish, a linguist who is coordinator of the Jamaican Language Unit at the University of the West Indies, the Bible translation is a big step toward getting the state to eventually embrace the creole language created by slaves.

- Di Jamiekan Nyuu Testiment (Jamaican Diglot New Testament with KJV) Archived 2020-12-11 at the Wayback Machine, British & Foreign Bible Society. Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- "Matyu 6 Di Jamiekan Nyuu Testiment". bible.com. Bible Society of the West Indies. 2012. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- Matthew 6:9–13

- Forrester, Clive (Mar 24, 2020). "Writing Ms. Lou Right: Language, Identity, and the Official Jamaican Orthography". www.cliveforrester.com. Retrieved May 14, 2022.

General sources

- Alleyne, Mervyn C. (1980). Comparative Afro-American: An Historical Comparative Study of English-based Afro-American Dialects of the New World. Koroma.

- Bailey, Beryl L (1966). Jamaican Creole Syntax. Cambridge University Press.

- Brown-Blake, Celia (2008). "The right to linguistic non-discrimination and Creole language situations". Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages. 23: 32–74. doi:10.1075/jpcl.23.1.03bro.

- Cassidy, Frederic (1971). Jamaica Talk: Three Hundred Years of English Language in Jamaica. London: MacMillan Caribbean.

- Cassidy, Frederic; Le Page, R. B. (1980). Dictionary of Jamaican English. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- DeCamp, David (1961), "Social and geographic factors in Jamaican dialects", in Le Page, R. B. (ed.), Creole Language Studies, London: Macmillan, pp. 61–84

- DeCamp, David (1977), "The Development of Pidgin and Creole Studies", in Valdman, A. (ed.), Pidgin and Creole Linguistics, Bloomington: Indiana University Press

- Devonish, H.; Harry, Otelamate G. (2004), "Jamaican phonology", in Kortman, B.; Shneider E. W. (eds.), A Handbook of Varieties of English, phonology, vol. 1, Berlin: Mouton De Gruyter, pp. 441–471

- Gibson, Kean (1988), "The Habitual Category in Guyanese and Jamaican Creoles", American Speech, 63 (3): 195–202, doi:10.2307/454817, JSTOR 454817

- Hancock, Ian (1985), "More on Poppy Show", American Speech, 60 (2): 189–192, doi:10.2307/455318, JSTOR 455318

- Harry, Otelemate G. (2006), "Jamaican Creole", Journal of the International Phonetic Association, 36 (1): 125–131, doi:10.1017/S002510030600243X

- Ramazani, Jahan; Ellmann, Richard; O'Clair, Robert, eds. (2003). The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry. Vol. 2: Contemporary Poetry (3rd ed.). Norton. ISBN 0-393-97792-7.

- Irvine, Alison (2004), "A Good Command of the English Language: Phonological Variation in the Jamaican Acrolect", Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, 19 (1): 41–76, doi:10.1075/jpcl.19.1.03irv

- Lawton, David (1984), "Grammar of the English-Based Jamaican Proverb", American Speech, 59 (2): 123–130, doi:10.2307/455246, JSTOR 455246

- Mufwene, Salikoko S. (1 January 1983). "Observations on Time Reference in Jamaican and Guyanese Creoles". English World-Wide. A Journal of Varieties of English. 4 (2): 199–229. doi:10.1075/eww.4.2.04muf. ISSN 0172-8865.

- Meade, R.R. (2001). Acquisition of Jamaican Phonology. Dordrecht: Holland Institute of Linguistics.

- Patrick, Peter L. (1995), "Recent Jamaican Words in Sociolinguistic Context", American Speech, 70 (3): 227–264, doi:10.2307/455899, JSTOR 455899

- Patrick, Peter L. (1999). Urban Jamaican Creole: Variation in the Mesolect. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins.

- Patrick, Peter L. (2007), "Jamaican Patwa (English Creole)", Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages, Battlebridge Publications, 24 (1)

- Rickford, John R. (1987). Dimensions of a Creole Continuum: History, Texts, Linguistic Analysis of Guyanese. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Velupillai, Viveka (2015), Pidgins, Creoles & Mixed Languages, John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 9789027252715

- Winford, Donald (1985), "The Syntax of Fi Complements in Caribbean English Creole", Language, 61 (3): 588–624, doi:10.2307/414387, JSTOR 414387