Joshua 20

Joshua 20 is the twentieth chapter of the Book of Joshua in the Hebrew Bible or in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1] According to Jewish tradition the book was attributed to the Joshua, with additions by the high priests Eleazar and Phinehas,[2][3] but modern scholars view it as part of the Deuteronomistic History, which spans the books of Deuteronomy to 2 Kings, attributed to nationalistic and devotedly Yahwistic writers during the time of the reformer Judean king Josiah in 7th century BCE.[3][4] This chapter records the designation of the cities of refuge,[5] a part of a section comprising Joshua 13:1–21:45 about the Israelites allotting the land of Canaan.[6]

| Joshua 20 | |

|---|---|

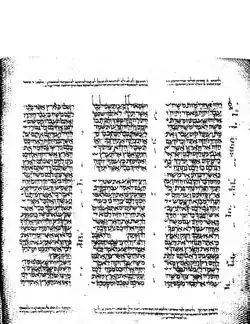

The pages containing the Book of Joshua in Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | Book of Joshua |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 1 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 6 |

Text

This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 9 verses.

Textual witnesses

Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[7]

Extant ancient manuscripts of a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint (originally was made in the last few centuries BCE) include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century) and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[8][lower-alpha 1]

Old Testament references

Analysis

The narrative of Israelites allotting the land of Canaan comprising verses 13:1 to 21:45 of the Book of Joshua and has the following outline:[11]

- A. Preparations for Distributing the Land (13:1–14:15)

- B. The Allotment for Judah (15:1–63)

- C. The Allotment for Joseph (16:1–17:18)

- D. Land Distribution at Shiloh (18:1–19:51)

- E. Levitical Distribution and Conclusion (20:1–21:45)

- 1. Cities of Refuge (20:1–9)

- a. Regulations for Cities of Refuge (20:1–6)

- b. Designation of Cities of Refuge (20:7–9)

- 2. Levitical Cities (21:1–42)

- a. Approach to Joshua and Eleazar (21:1–3)

- b. Initial Summary (21:4–8)

- c. Priestly Kohathite Allotment (21:9–19)

- d. Non-Priestly Kohathite Allotment (21:20–26)

- e. Gershonite Allotment (21:27–33)

- f. Merarite Allotment (21:34–40)

- g. Levitical Summary (21:41–42)

- 3. Summary of Divine Faithfulness (21:43–45)

- 1. Cities of Refuge (20:1–9)

Regulations for Cities of Refuge (20:1–6)

The instructions regarding cities of refuge are given in Numbers 35:9–28 and Deuteronomy 4:41–43; 19:1–10 and now are implemented into practice. The main topic is the 'accidental homicide' to a form of justice deriving from familial relations in a tribal context.[12] An 'avenger of blood' was appointed by the familial group to exact 'blood for blood' in cases of homicide for the protection of the family group.[12] The Hebrew word for 'avenger' can also be translated as 'redeemer' (Ruth 2:20).[12] The perpetrator of an accidental homicide, as exemplified in Numbers 35:22–23 and Deuteronomy 19:5, is permitted to escape to designated cities for asylum until the person's guilt or innocence is determined: first, by the elders at the gates of the city, which may simply be a formal request for sanctuary (verse 4), then followed by a trial before the ‘ê-ḏāh, , or 'congregation', that is, the whole people constituted as a religious assembly (verse 6; cf. Numbers 35:12).[12] One criterion for deciding intentionality is whether 'there had been previous enmity between the parties' (verse 5b, cf. Deuteronomy 19:4b, Num 35:23b).[12] The provision that the refugee must remain in that city of refuge until the death of the high priest at that period of time (verse 6b) may be intended to set a time-limit on the stalemate produced by a verdict of innocent, which nevertheless cannot revoke the principle right of blood vengeance (Numbers 35:27c).[12]

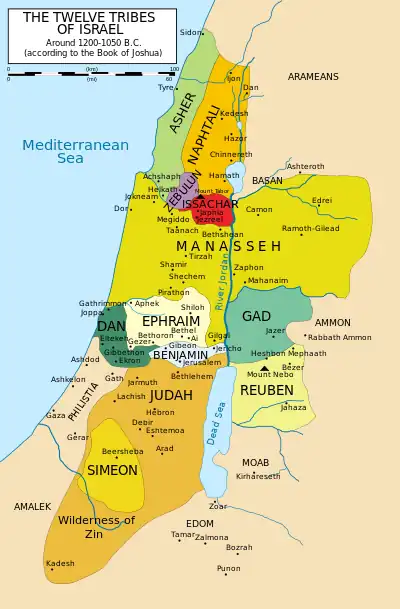

Designation of Cities of Refuge (20:7–9)

The designated cities of refuge, from north to south, relative to the Jordan River were:[13]

| West of Jordan | East of Jordan |

|---|---|

| 1. Kedesh, in Naphtali. | 1. Golan, in Bashan (East Manasseh) |

| 2. Shechem, in Mount Ephraim | 2. Ramoth-Gilead, in Gad. |

| 3. Hebron, in Judah | 3. Bezer, in Reuben |

All the cities of refuge are also levitical cities (cf. Joshua 21),[12] could be for some reasons:[14][15]

- The cases might be more impartially examined and justly determined by the Levites who presumably better in understanding and following the law of God, without being biased by any group interest

- The Levites might be better to counsel revengeful persons to restrain any harsh actions and to provide worship services for the refugee who for the time being might not go up to the house of the Lord.[14]

The cities were all upon mountains, so they might be seen from afar by those who fled there, and seated at a convenient distance one from another, for the benefit of the several tribes,[14] approximately within half a day reach from any part of most of the country.[16]

Verse 9

- These were the cities appointed for all the children of Israel and for the stranger who dwelt among them, that whoever killed a person accidentally might flee there, and not die by the hand of the avenger of blood until he stood before the congregation.[17]

- "The stranger“: The existence of a class of “naturalized foreigners” in Israel was known to comprise:[13]

- The “mixed multitude” that came out of Egypt (Exodus 12:38)

- The remains of the Canaanites who were never 'wholly extirpated'

- Captives taken in war

- Fugitives, hired servants, merchants

The census of these in Solomon’s time gave a return of 153,600 males (2 Chronicles 2:17), which was nearly equal to about a tenth of the whole population.[13]

Notes

- The whole book of Joshua is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[9]

References

- Halley 1965, p. 164.

- Talmud, Baba Bathra 14b–15a)

- Gilad, Elon. Who Really Wrote the Biblical Books of Kings and the Prophets? Haaretz, June 25, 2015. Summary: The paean to King Josiah and exalted descriptions of the ancient Israelite empires beg the thought that he and his scribes lie behind the Deuteronomistic History.

- Coogan 2007, p. 314 Hebrew Bible.

- Coogan 2007, p. 344 Hebrew Bible.

- McConville 2007, p. 158.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. - Joshua 20, Berean Study Bible

- Firth 2021, pp. 29–30.

- McConville 2007, p. 172.

- Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Joshua 20. Accessed 28 April 2019.

- Benson, Joseph. Commentary on the Old and New Testaments: Joshua 20, accessed 9 July 2019

- Exell, Joseph S.; Spence-Jones, Henry Donald Maurice (Editors). On "Joshua 20". In: The Pulpit Commentary. 23 volumes. First publication: 1890. Accessed 24 April 2019.

- Matthew Henry, Concise Commentary on the Whole Bible. "Joshua 20". Accessed on 13 July 2018.

- Joshua 20:9 NKJV

Sources

- Beal, Lissa M. Wray (2019). Longman, Tremper, III; McKnight, Scot (eds.). Joshua. The Story of God Bible Commentary. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 978-0310490838.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: editors list (link) - Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195288810.

- Firth, David G. (2021). Joshua: Evangelical Biblical Theology Commentary. Evangelical Biblical Theology Commentary (EBTC) (illustrated ed.). Lexham Press. ISBN 9781683594406.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Harstad, Adolph L. (2004). Joshua. Concordia Publishing House. ISBN 978-0570063193.

- Hayes, Christine (2015). Introduction to the Bible. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300188271.

- Hubbard, Robert L (2009). Joshua. The NIV Application Commentary. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310209348.

- McConville, Gordon (2007). "9. Joshua". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 158–176. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Rösel, Hartmut N. (2011). Joshua. Historical commentary on the Old Testament. Vol. 6 (illustrated ed.). Peeters. ISBN 978-9042925922.

- Webb, Barry G. (2012). The Book of Judges. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802826282.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

- Jewish translations:

- Yehoshua - Joshua - Chapter 20 (Judaica Press). Hebrew text and English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Joshua chapter 20. Bible Gateway