Free France

Free France (French: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general Charles de Gaulle, Free France was established as a government-in-exile in London in June 1940 after the Fall of France during World War II and fought the Axis as an Allied nation with its Free French Forces (Forces françaises libres). Free France also supported the resistance in Nazi-occupied France, known as the French Forces of the Interior, and gained strategic footholds in several French colonies in Africa.

Free France | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940–1944 | |||||||||

| Anthem: "La Marseillaise" (official) "The Song of the Partisan" (unofficial) | |||||||||

See map legend for color descriptions; sky blue = colonies under the control of Free France after Operation Torch | |||||||||

| Status | Government-in-exile (until November 1942) Provisional government over unoccupied and liberated territories (after November 1942) | ||||||||

| Capital | Paris (de jure) London (de facto) (until November 1942) Brazzaville Algiers (de facto) (after November 1942) | ||||||||

| Common languages | French | ||||||||

| Religion | Secular State | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | French | ||||||||

| Leader | |||||||||

• 1940–1944 | Charles de Gaulle | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||

| 18 June 1940 | |||||||||

| 11 July 1940 | |||||||||

| 24 September 1941 | |||||||||

| 3 June 1943 | |||||||||

| 8 February 1944 | |||||||||

| 3 June 1944 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

Following the defeat of the Third Republic by Nazi Germany, Marshal Philippe Pétain led efforts to negotiate an armistice and established a German puppet state known as Vichy France. Opposed to the idea of an armistice, de Gaulle fled to Britain, and from there broadcast the Appeal of 18 June (Appel du 18 juin) exhorting the French people to resist the Nazis and join the Free French Forces. On 27 October 1940, the Empire Defense Council (Conseil de défense de l'Empire)—later the French National Committee (Comité national français or CNF)—formed to govern French territories in central Africa, Asia, and Oceania that had heeded the 18 June call.

Initially, with the exception of French possessions in the Pacific, India, and Equatorial Africa,[note 1] all the territories of the French colonial empire rejected de Gaulle's appeal and reaffirmed their loyalty to Marshall Pétain and the Vichy government.[1] It was only progressively, often with the decisive military intervention of the Allies, that Free France took over more Vichy possessions, securing the majority of colonies by November 1942.

The Free French fought both Axis and Vichy troops and served in almost every major campaign, from the Middle East to Indochina and North Africa. The Free French Navy operated as an auxiliary force to the Royal Navy and, in the North Atlantic, to the Royal Canadian Navy.[2] Free French units also served in the Royal Air Force, Soviet Air Force, and British SAS, before larger commands were established directly under the control of the government-in-exile. On 13 July 1942, "Free France" was officially renamed Fighting France (France combattante) to mark the struggle against the Axis both externally and within occupied France.

From a legal perspective, exile officially ended after the reconquest of North Africa since it allowed the Free French government to relocate from London to Algiers.[note 2] From there, the French Committee of National Liberation (Comité français de Libération nationale, CFLN) was formed as the provisional government of all French. The government returned to Paris following its liberation by the 2nd Armoured Free French Division and Resistance forces on 25 August 1944, ushering in the Provisional Government of the French Republic (gouvernement provisoire de la République française or GPRF). The provisional government ruled France until the end of the war and afterwards to 1946, when the Fourth Republic was established, thus ending the series of interim regimes that had succeeded the Third Republic after its fall in 1940.

On 1 August 1943, L'Armée d'Afrique formally united with the Free French Forces to form the French Liberation Army. By mid-1944, the forces of this army numbered more than 400,000, and they participated in the Normandy landings and the invasion of southern France, eventually leading the drive on Paris. Soon they were fighting in Alsace, the Alps and Brittany. By the end of the war, they were 1,300,000 strong—the fourth-largest Allied army in Europe—and took part in the Allied advance through France and invasion of Germany. The Free French government re-established a provisional republic after the liberation, preparing the ground for the Fourth Republic in 1946.

Definition

Historically, an individual became "Free French" by enlisting in the military units organised by the CFN or by employment by the civilian arm of the Committee. On 1 August 1943 after the merger of CFN and representatives of the former Vichy regime in North Africa to form the CFLN earlier in June, the FFF and the Army of Africa (constituting a major part of the Vichy regular forces allowed by the 1940 armistice) were merged to form the French Liberation Army, Armée française de la Libération, and all subsequent enlistments were in this combined force.

In many sources, Free French describes any French individual or unit that fought against Axis forces after the June 1940 armistice. Postwar, to settle disputes over the Free French heritage, the French government issued an official definition of the term. Under this "ministerial instruction of July 1953" (instruction ministérielle du 29 juillet 1953), only those who served with the Allies after the Franco-German armistice in 1940 and before 1 August 1943 may correctly be called "Free French".[3]

History

Prelude

On 10 May 1940, Nazi Germany invaded France and the Low Countries, rapidly defeating the Dutch and Belgians, while armoured units attacking through the Ardennes cut off the Franco-British strike force in Belgium. By the end of May, the British and French northern armies were trapped in a series of pockets, including Dunkirk, Calais, Boulogne, Saint-Valery-en-Caux and Lille. The Dunkirk evacuation was only made possible by the resistance of these troops, particularly the French army divisions at Lille.[4]

From 27 May to 4 June, over 200,000 members of the British Expeditionary Force and 140,000 French troops were evacuated from Dunkirk.[5] Neither side viewed this as the end of the battle; French evacuees were quickly returned to France and many fought in the June battles. After being evacuated from Dunkirk, Alan Brooke landed in Cherbourg on 2 June to reform the BEF, along with the 1st Canadian Division, the only remaining fully equipped formation in Britain. Contrary to what is often assumed, French morale was higher in June than May and they easily repulsed an attack in the south by Fascist Italy. A defensive line was re-established along the Somme but much of the armour was lost in Northern France; they were also crippled by shortages of aircraft, the vast majority incurred when airfields were over-run, rather than air combat.[6]

On 1 June, Charles de Gaulle was promoted to brigadier general; on 5 June, Prime Minister Paul Reynaud appointed him Under Secretary of State for Defence, a junior post in the French cabinet.[7] De Gaulle was known for his willingness to challenge accepted ideas; in 1912, he asked to be posted to Pétain's regiment, whose maxim 'Firepower kills' was then in stark contrast to the prevailing orthodoxy.[8] He was also a long-time advocate of the modern armoured warfare ideas applied by the Wehrmacht, and commanded the 4th Armoured Division at the Battle of Montcornet.[9] However, he was not personally popular; significantly, none of his immediate military subordinates joined him in 1940.[10]

The new French commander Maxime Weygand was 73 years old and like Pétain, an Anglophobe who viewed Dunkirk as another example of Britain's unreliability as an ally; de Gaulle later recounted he 'gave up hope' when the Germans renewed their attack on 8 June and demanded an immediate Armistice.[11] De Gaulle was one of a small group of government ministers who favoured continued resistance and Reynaud sent him to London in order to negotiate the proposed union between France and Britain. When this plan collapsed, he resigned on 16 June and Pétain became President of the Council.[12] De Gaulle flew to Bordeaux on 17th but returned to London the same day when he realised Pétain had already agreed an armistice with the Axis Powers.[9]

De Gaulle rallies the Free French

On 18 June 1940, General de Gaulle spoke to the French people via BBC radio, urging French soldiers, sailors and airmen to join in the fight against the Nazis:

- "France is not alone! She is not alone! She has a great empire behind her! Together with the British Empire, she can form a bloc that controls the seas and continue the struggle. She may, like England, draw upon the limitless industrial resources of the United States".[9]

Some members of the British Cabinet had reservations about de Gaulle's speech, fearing that such a broadcast could provoke the Pétain government into handing the French fleet over to the Nazis,[13] but British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, despite his own concerns, agreed to the broadcast.

In France, de Gaulle's "Appeal of 18 June" (Appel du 18 juin) was not widely heard that day but, together with his BBC broadcasts[14] in subsequent days and his later communications, came to be widely remembered throughout France and its colonial empire as the voice of national honour and freedom.

Armistice

On 19 June, de Gaulle again broadcast to the French nation saying that in France, "all forms of authority had disappeared" and since its government had "fallen under the bondage of the enemy and all our institutions have ceased to function", that it was "the clear duty" of all French servicemen to fight on.[15]

This would form the essential legal basis of de Gaulle's government in exile, that the armistice soon to be signed with the Nazis was not merely dishonourable but illegal, and that in signing it, the French government would itself be committing treason.[15] On the other hand, if Vichy was the legal French government as some such as Julian T. Jackson have argued, de Gaulle and his followers were revolutionaries, unlike the Dutch, Belgian, and other governments in exile in London.[16] A third option might be that neither considered that a fully free, legitimate, sovereign, and independent successor state to the Third Republic existed following the Armistice, as both Free France and Vichy France refrained from making that implicit claim by studiously avoiding using the word "republic" when referring to themselves. In Vichy's case, underlying reasons were compounded by ideals of a Révolution nationale stamping out France's republican heritage.

On 22 June 1940, Marshal Pétain signed an armistice with Germany, followed by a similar one with Italy on 24 June; both of these came into force on 25 June.[17] After a parliamentary vote on 10 July, Pétain became the leader of the newly established authoritarian regime known as Vichy France, the town of Vichy being the seat of government. De Gaulle was tried in absentia in Vichy France and sentenced to death for treason.[18] He, on the other hand, regarded himself as the last remaining member of the legitimate Reynaud government and considered Pétain's assumption of power to be an unconstitutional coup d'état.

Beginnings of the Free French forces

Despite de Gaulle's call to continue the struggle, few French forces initially pledged their support. By the end of July 1940, only about 7,000 soldiers had joined the Free French Army in England.[20][21] Three-quarters of French servicemen in Britain requested repatriation.[22]

France was bitterly divided by the conflict. Frenchmen everywhere were forced to choose sides, and often deeply resented those who had made a different choice.[23] One French admiral, René-Émile Godfroy, voiced the opinion of many of those who decided not to join the Free French forces, when in June 1940, he explained to the exasperated British why he would not order his ships from their Alexandria harbour to join de Gaulle:

- "For us Frenchmen, the fact is that a government still exists in France, a government supported by a Parliament established in non-occupied territory and which in consequence cannot be considered irregular or deposed. The establishment elsewhere of another government, and all support for this other government would clearly be rebellion."[23]

Equally, few Frenchmen believed that Britain could stand alone. In June 1940, Pétain and his generals told Churchill that "in three weeks, England will have her neck wrung like a chicken".[24] Of France's far-flung empire, only the French domains of St Helena (on 23 June at the initiative of Georges Colin, honorary consul of the domains[25]) and the Franco-British ruled New Hebrides condominium in the Pacific (on 20 July) answered de Gaulle's call to arms. It was not until late August that Free France would gain significant support in French Equatorial Africa.[26]

Unlike the troops at Dunkirk or naval forces at sea, relatively few members of the French Air Force had the means or opportunity to escape. Like all military personnel trapped on the mainland, they were functionally subject to the Pétain government: "French authorities made it clear that those who acted on their own initiative would be classed as deserters, and guards were placed to thwart efforts to get on board ships."[27] In the summer of 1940, around a dozen pilots made it to England and volunteered for the RAF to help fight the Luftwaffe.[28][29] Many more, however, made their way through long and circuitous routes to French territories overseas, eventually regrouping as the Free French Air Force.[30]

The French Navy was better able to immediately respond to de Gaulle's call to arms. Most units initially stayed loyal to Vichy, but about 3,600 sailors operating 50 ships around the world joined with the Royal Navy and formed the nucleus of the Free French Naval Forces (FFNF; in French: FNFL).[21] France's surrender found her only aircraft carrier, Béarn, en route from the United States loaded with a precious cargo of American fighter and bomber aircraft. Unwilling to return to occupied France, but likewise reluctant to join de Gaulle, Béarn instead sought harbour in Martinique, her crew showing little inclination to side with the British in their continued fight against the Nazis. Already obsolete at the start of the war, she would remain in Martinique for the next four years, her aircraft rusting in the tropical climate.[31]

Many of the men in the French colonies felt a special need to defend France, their distant "motherland", eventually making up two-thirds of de Gaulle's Free French Forces.

Composition

The Free French forces included men from the French Pacific Islands. Mainly coming from Tahiti, there were 550 volunteers in April 1941. They would serve through the North African campaign (including the Battle of Bir Hakeim), the Italian Campaign and much of the Liberation of France. In November 1944, 275 remaining volunteers were repatriated and replaced with men of French Forces of the Interior to deal better with the cold weather.[32]

The Free French forces also included 5,000 non-French Europeans, mainly serving in units of the Foreign Legion. There were also escaped Spanish Republicans, veterans of the Spanish Civil War. In August 1944, they numbered 350 men.[33]

The ethnic composition of divisions varied. The main common difference, before the period of August to November 1944, was armoured divisions and armour and support elements within infantry divisions were constituted of mainly white French soldiers and infantry elements of infantry divisions were mainly made up of colonial soldiers. Nearly all NCOs and officers were white French. Both the 2e Division Blindée and 1er Division Blindée were made up of around 75% Europeans and 25% Mahgrebians, which is why the 2e Division Blindée was selected for the Liberation of Paris.[34] The 5e Division Blindée was almost entirely made up of white Frenchmen.

Records for the Italian campaign show that both the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division and 2nd Moroccan Infantry Division were made up of 60% Mahgrebians and 40% Europeans, while the 4th Moroccan Infantry Division was made up of 65% Mahgrebians and 35% Europeans.[35] The three North African divisions had one brigade of North African soldiers in each division replaced with a brigade of French Forces of the Interior in January 1945.[36] Both the 1st Free French Division and 9th Colonial Infantry Division contained a strong contingent of Tirailleurs Sénégalais brigades. The 1st Free French Division also contained a mixed brigade of French Troupes de marine and the Pacific island volunteers.[32] It also included the Foreign Legion Brigades. In late September and early October 1944, both the Tirailleurs Sénégalais brigades and Pacific Islanders were replaced by brigades of troops recruited from mainland France.[37] This was also when many new Infantry divisions (12 overall) began to be recruited from mainland France, including the 10th Infantry Division and many Alpine Infantry Divisions. The 3rd Armoured Division was also created in May 1945 but saw no combat in the war.

The Free French units in the Royal Air Force, Soviet Air Force, and British SAS were mainly composed of men from metropolitan France.

Before the addition of the assemblies of Northern Africa and the loss of the runaways who fled France and went to Spain in the spring of 1943 (10,000 according to Jean-Noël Vincent's calculations), a report by the major state general of the Free French Forces in London from October 30, 1942 records 61,670 combatants in the Army, of which 20,200 were from colonies and 20,000 were from the Levant's special troops (non-Free French forces).[38]

In May 1943, citing the Joint Planning Staff, Jean-Louis Crémieux-Brilhac alludes to 79,600 men who constitute ground forces, including 21,500 men from special Syro-Lebanese troops, 2,000 men of color supervised by Free French Forces in northern Palestine, and 650 soldiers assigned to the general headquarters in London.[39]

According to the tally of Henri Écochard, an ex-Free French Forces serviceman, there were at least 54,500 soldiers.[40]

In 2009, in his work on the Free French Forces, Jean-François Muracciole, a French historian specializing in Free France, reevaluated his count with that of Henri Écochard, while considering that Écochard's list had greatly underestimated the number of colonial combatants. According to Muracciole, between the creation of the Free French forces in the Summer 1940 and the merger with the Army of Africa in summer 1943, 73,300 men fought for Free France. This included 39,300 French (from metropolitan France and colonial settlers), 30,000 colonial soldiers (mostly from sub-Saharan Africa) and 3,800 foreigners. They were divided up as follows:[41][42]

Army: 50,000;

Naval: 12,500;

Aviation: 3,200;

Communications in France: 5,700;

Free French Forces committees: 1,900.

General Leclerc's second armored division included two units of female volunteers: The Rochambeau Group with the Army (dozens of women) and the Woman Service of the Naval Fleet with the Navy (9 women). Their role consisted of administering first aid to the first line of injured soldiers (often to stop bleeding) before evacuating them by stretcher to ambulances and then driving these ambulances under enemy fire to care centers several kilometers behind the lines.[43]

The following anecdote by Pierre Clostermann[44] suggests the spirit of the times in the Free French Forces; a commander reproaches one of Clostermann's comrades for having yellow shoes and a yellow sweater under his uniform, to which the comrade responds: "My Commander, I am a civilian who voluntarily came to fight the war that the soldiers don't want to fight!"

Cross of Lorraine

The argent rhomboid field is defaced with a gules Lorraine cross, the emblem of the Free French.

Capitaine de corvette Thierry d'Argenlieu[45] suggested the adoption of the Cross of Lorraine as a symbol of the Free French. This was chosen to recall the perseverance of Joan of Arc, patron saint of France, whose symbol it had been, the province where she was born, and now partially annexed into Alsace-Lorraine by Nazi Germany, and as a response to the symbol of national-socialism, the Nazi swastika.[46]

In his general order No. 2 of 3 July 1940, Vice admiral Émile Muselier, two days after assuming the post of chief of the naval and air forces of the Free French, created the naval jack displaying the French colours with a red cross of Lorraine, and a cockade, which also featured the cross of Lorraine. Modern ships that share the same name as ships of the FNFL—such as Rubis and Triomphant—are entitled to fly the Free French naval jack as a mark of honour.

A monument on Lyle Hill in Greenock, in the shape of the Cross of Lorraine combined with an anchor, was raised by subscription as a memorial to the Free French naval vessels which sailed from the Firth of Clyde to take part in the Battle of the Atlantic. It has plaques commemorating the loss of the Flower-class corvettes Alyssa and Mimosa, and of the submarine Surcouf.[47] Locally, it is also associated with the memory of the loss of the destroyer Maillé Brézé which blew up at the Tail of the Bank.

Mers El Kébir and the fate of the French Navy

After the fall of France, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill feared that, in German or Italian hands, the ships of the French Navy would pose a grave threat to the Allies. He therefore insisted that French warships either join the Allies or else adopt neutrality in a British, French, or neutral port. Churchill was determined that French warships would not be in a position to support a German invasion of Britain, though he feared that a direct attack on the French Navy might cause the Vichy regime to actively ally itself with the Nazis.[22]

On 3 July 1940, Admiral Marcel-Bruno Gensoul was provided an ultimatum by the British:

It is impossible for us, your comrades up to now, to allow your fine ships to fall into the power of the German enemy. We are determined to fight on until the end, and if we win, as we think we shall, we shall never forget that France was our Ally, that our interests are the same as hers, and that our common enemy is Germany. Should we conquer we solemnly declare that we shall restore the greatness and territory of France. For this purpose we must make sure that the best ships of the French Navy are not used against us by the common foe. In these circumstances, His Majesty's Government have instructed me to demand that the French Fleet now at Mers el Kebir and Oran shall act in accordance with one of the following alternatives;

(a) Sail with us and continue the fight until victory against the Germans.

(b) Sail with reduced crews under our control to a British port. The reduced crews would be repatriated at the earliest moment.

If either of these courses is adopted by you we will restore your ships to France at the conclusion of the war or pay full compensation if they are damaged meanwhile.

(c) Alternatively if you feel bound to stipulate that your ships should not be used against the Germans lest they break the Armistice, then sail them with us with reduced crews to some French port in the West Indies—Martinique for instance—where they can be demilitarised to our satisfaction, or perhaps be entrusted to the United States and remain safe until the end of the war, the crews being repatriated.

If you refuse these fair offers, I must with profound regret, require you to sink your ships within 6 hours.

Finally, failing the above, I have the orders from His Majesty's Government to use whatever force may be necessary to prevent your ships from falling into German hands.[48]

Gensoul's orders allowed him to accept internment in the West Indies,[49] but after a discussion lasting ten hours, he rejected all offers, and British warships commanded by Admiral James Somerville attacked French ships during the attack on Mers-el-Kébir in Algeria, sinking or crippling three battleships.[22] Because the Vichy government only said that there had been no alternatives offered, the attack caused great bitterness in France, particularly in the Navy (over 1,000 French sailors were killed), and helped to reinforce the ancient stereotype of perfide Albion. Such actions discouraged many French soldiers from joining the Free French forces.[23]

Despite this, some French warships and sailors did remain on the Allied side or join the FNFL later, such as the mine-laying submarine Rubis, whose crew voted almost unanimously to fight alongside Britain,[50] the destroyer Le Triomphant, and the then-largest submarine in the world, Surcouf. The first loss of the FNFL occurred on 7 November 1940, when the patrol boat Poulmic struck a mine in the English Channel.[51]

Most ships that had remained on the Vichy side and were not scuttled with the main French fleet in Toulon, mostly those in the colonies that had remained loyal to Vichy until the end of the regime through the Case Anton Axis invasion and occupation of the zone libre and Tunisia, changed sides then.

In November 1940, around 1,700 officers and men of the French Navy took advantage of the British offer of repatriation to France, and were transported home on a hospital ship travelling under the International Red Cross. This did not stop the Germans from torpedoing the ship, and 400 men were drowned.[52]

The FNFL, commanded first by Admiral Emile Muselier and then by Philippe Auboyneau and Georges Thierry d'Argenlieu, played a role in the liberation of French colonies throughout the world including Operation Torch in French north Africa, escorting convoys during the Battle of the Atlantic, in supporting the French Resistance in non-Free French territories, in Operation Neptune in Normandy and Operation Dragoon in Provence for the liberation of mainland France, and in the Pacific War.

In total during the war, around 50 major ships and a few dozen minor and auxiliary ships were part of the Free French navy. It also included half a dozen battalions of naval infantry and commandos, as well as naval aviation squadrons, one aboard HMS Indomitable and one squadron of anti-submarine Catalinas. The French merchant marine siding with the Allies counted over 170 ships.

Struggle for control of the French colonies

With metropolitan France firmly under Germany's thumb and the Allies too weak to challenge this, de Gaulle turned his attention to France's vast overseas empire.

African campaign and the Empire Defence Council

De Gaulle was optimistic that France's colonies in western and central Africa, which had strong trading links with British territories, might be sympathetic to the Free French.[53] Pierre Boisson, the governor-general of French Equatorial Africa, was a staunch supporter of the Vichy regime, unlike Félix Éboué, the governor of French Chad, a subsection of the overall colony. Boisson was soon promoted to "High Commissioner of Colonies" and transferred to Dakar, leaving Éboué with more direct authority over Chad. On 26 August, with the help of his top military official, Éboué pledged his colony's allegiance to Free France.[54] By the end of August, all of French Equatorial Africa (including the League of Nations mandate French Cameroun) had joined Free France, with the exception of French Gabon.[55][56]

With these colonies came vital manpower—a large number of African colonial troops, who would form the nucleus of de Gaulle's army. From July to November 1940, the FFF would engage in fighting with troops loyal to Vichy France in Africa, with success and failure on both sides.

In September 1940 an Anglo French naval force fought the Battle of Dakar, also known as Operation Menace, an unsuccessful attempt to capture the strategic port of Dakar in French West Africa. The local authorities were not impressed by the Allied show of strength, and had the better of the naval bombardment which followed, leading to a humiliating withdrawal by the Allied ships. So strong was de Gaulle's sense of failure that he even considered suicide.[57]

There was better news in November 1940 when the FFF achieved victory at the Battle of Gabon (or Battle of Libreville) under the very skilled General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque (General Leclerc).[58] De Gaulle personally surveyed the situation in Chad, the first African colony to join Free France, located on the southern border of Libya, and the battle resulted in free French forces taking Libreville, Gabon.[59]

By the end of November 1940 French Equatorial Africa was wholly under the control of Free France, but the failures at Dakar had led French West Africa to declare allegiance to Vichy, to which they would remain loyal until the fall of the regime in November 1942.

On 27 October 1940 the Empire Defence Council was established to organise and administer the imperial possessions under Free French rule, and as an alternative provisional French government. It was constituted of high-ranking officers and the governors of the free colonies, notably governor Félix Éboué of Chad. Its creation was announced by the Brazzaville Manifesto that day. La France libre was what de Gaulle claimed to represent, or rather, as he put it simply, "La France"; Vichy France was a "pseudo government", an illegal entity.[60]

In 1941–1942, the African FFF slowly grew in strength and even expanded operations north into Italian Libya. In February 1941, Free French Forces invaded Cyrenaica, again led by Leclerc, capturing the Italian fort at the oasis of Kufra.[58] In 1942, Leclerc's forces and soldiers from the British Long Range Desert Group captured parts of the province of Fezzan.[58] At the end of 1942, Leclerc moved his forces into Tripolitania to join British Commonwealth and other FFF forces in the Run for Tunis.[58]

Asia and the Pacific

France also had possessions in Asia and the Pacific, and these far-flung colonies would experience similar problems of divided loyalties. French India and the French South Pacific colonies of New Caledonia, French Polynesia and the New Hebrides joined Free France in the summer 1940, drawing official American interest.[55] These South Pacific colonies would later provide vital Allied bases in the Pacific Ocean during the war with Japan.

French Indochina was invaded by Japan in September 1940, although for most of the war the colony remained under nominal Vichy control. On 9 March 1945, the Japanese launched a coup and took full control of Indochina by the beginning of May. Japanese rule in Indochina lasted until the successful August Revolution which was led by communist-dominated Viet Minh, and the entry of British and Chinese forces.

From June 1940 until February 1943, the concession of Guangzhouwan (Kouang-Tchéou-Wan or Fort-Boyard), in South China, remained under the administration of Free France. The Republic of China, after the fall of Paris in 1940, recognised the London-exiled Free French government as Guangzhouwan's legitimate authority and established diplomatic relations with them, something facilitated by the fact that the colony was surrounded by the Republic of China's territory and was not in physical contact with French Indochina. In February 1943 the Imperial Japanese Army invaded and occupied the leased territory.[61]

North America

In North America, Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (near Newfoundland) joined the Free French after an "invasion" on 24 December 1941 by Rear Admiral Emile Muselier and the forces he was able to load onto three corvettes and a submarine of the FNFL. The action at Saint-Pierre and Miquelon created a serious diplomatic incident with the United States, despite this being the first French possession in the Americas to join the Allies,[62] which doctrinally objected to the use of military means by colonial powers in the western hemisphere and recognised Vichy as the official French government.

Mainly because of this and of the often very frosty relations between Free France and the USA (with President Roosevelt's profound distrust of de Gaulle playing a key part in that, with him being firmly convinced that the general's aim was to create a South-American style junta and become the dictator of France[63]), other French possessions in the New World were among the last to defect from Vichy to the Allies (with Martinique holding out until July 1943).

Syria and East Africa

In 1941, the FFF fought alongside British Empire troops against the Italians in Italian East Africa during the East African Campaign.

In June 1941, during the Syria-Lebanon campaign (Operation Exporter), Free French Forces fighting alongside British Commonwealth forces faced substantial numbers of troops loyal to Vichy France—this time in the Levant. De Gaulle had assured Churchill that the French units in Syria would rise to the call of Free France, but this was not the case.[64] After bitter fighting, with around 1,000 dead on each side (including Vichy and Free French Foreign Legionnaires fratricide when the 13th Demi-Brigade (D.B.L.E.) clashed with the 6th Foreign Infantry Regiment near Damascus). General Henri Dentz and his Vichy Army of the Levant were eventually defeated by the largely British allied forces in July 1941.[64]

The British did not themselves occupy Syria; rather, the Free French General Georges Catroux was appointed High Commissioner of the Levant, and from this point, Free France would control both Syria and Lebanon until they became independent in 1946 and 1943 respectively. However, despite this success, the numbers of the FFF did not grow as much as had been wished for. Of nearly 38,000 Vichy French prisoners of war, just 5,668 men volunteered to join the forces of General de Gaulle; the remainder chose to be repatriated to France.[65]

Despite this bleak picture, by the end of 1941, the United States had entered the war, and the Soviet Union had also joined the Allied side, stopping the Germans outside Moscow in the first major reverse for the Nazis. Gradually the tide of war began to shift, and with it the perception that Hitler could at last be beaten. Support for Free France began to grow, though the Vichy French forces would continue to resist Allied armies—and the Free French—when attacked by them until the end of 1942.[66]

Creation of the French National Committee (CNF)

Reflecting the growing strength of Free France was the foundation of the French National Committee (French: Comité national français, CNF) in September 1941 and the official name change from France Libre to France combattante in July 1942.

The United States granted Lend-Lease support to the CNF on 24 November.

Madagascar

In June 1942, the British attacked the strategically important colony of French Madagascar, hoping to prevent its falling into Japanese hands and especially the use of Diego-Suarez's harbour as a base for the Imperial Japanese Navy. Once again the Allied landings faced resistance from Vichy forces, led by Governor-General Armand Léon Annet. On 5 November 1942, Annet, at last, surrendered. As in Syria, only a minority of the captured Vichy soldiers chose to join the Free French.[67] After the battle, Free French general Paul Legentilhomme was appointed High Commissioner for Madagascar.

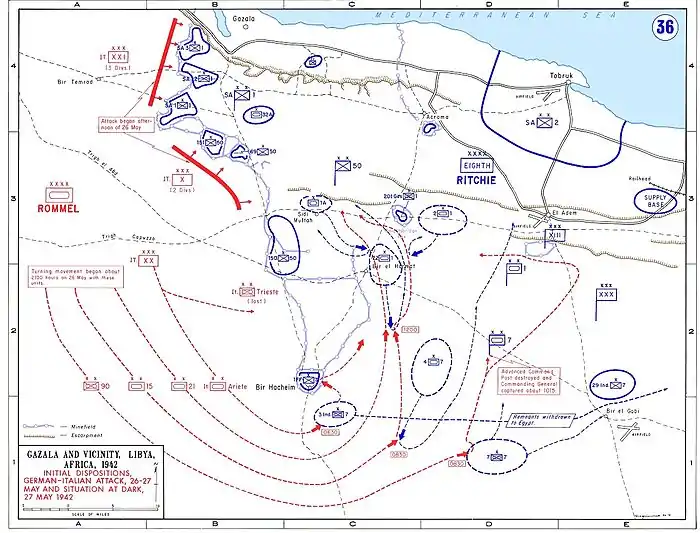

Battle of Bir Hakeim

Throughout 1942 in North Africa, British Empire forces fought a desperate land campaign against the Germans and Italians to prevent the loss of Egypt and the vital Suez canal. Here, fighting in the harsh Libyan desert, Free French soldiers distinguished themselves. General Marie Pierre Koenig and his unit—the 1st Free French Infantry Brigade—resisted the Afrika Korps at the Battle of Bir Hakeim in June 1942, although they were eventually obliged to withdraw, as Allied forces retreated to El Alamein, their lowest ebb in the North African campaign.[68] Koenig defended Bir Hakeim from 26 May to 11 June against superior German and Italian forces led by Generaloberst Erwin Rommel, proving that the FFF could be taken seriously by the Allies as a fighting force. British General Claude Auchinleck said on 12 June 1942, of the battle: "The United Nations need to be filled with admiration and gratitude, in respect of these French troops and their brave General Koenig".[69] Even Hitler was impressed, announcing to the journalist Lutz Koch, recently returned from Bir Hakeim:

You hear, Gentlemen? It is a new evidence that I have always been right! The French are, after us, the best soldiers! Even with its current birthrate, France will always be able to mobilise a hundred divisions! After this war, we will have to find allies able to contain a country which is capable of military exploits that astonish the world like they are doing right now in Bir-Hakeim![70]

Generalmajor Friedrich von Mellenthin wrote in his mémoirs Panzer Battles,

[I]n the whole course of the desert war, we never encountered a more heroic and well-sustained defence.[71][72]

First successes

From 23 October to 4 November 1942, Allied forces under general Bernard Montgomery, including the FFI, won the Second battle of El Alamein, driving Rommel's Afrika Korps out of Egypt and back into Libya. This was the first major success of a Western Allied army against the Axis powers, and marked a key turning point in the war.

Operation Torch

Soon afterwards in November 1942, the Allies launched Operation Torch in the west, an invasion of Vichy-controlled French North Africa. An Anglo-American force of 63,000 men landed in French Morocco and Algeria.[73] The long-term goal was to clear German and Italian troops from North Africa, enhance naval control of the Mediterranean, and prepare an invasion of Italy in 1943. The Allies had hoped that Vichy forces would offer only token resistance to the Allies, but instead they fought hard, incurring heavy casualties.[74] As a French foreign legionnaire put it after seeing his comrades die in an American bombing raid: "Ever since the fall of France, we had dreamed of deliverance, but we did not want it that way".[74]

After 8 November 1942 putsch by the French resistance that prevented the 19th Corps from responding effectively to the allied landings around Algiers the same day, most Vichy figures were arrested (including General Alphonse Juin, chief commander in North Africa, and Vichy admiral François Darlan). However, Darlan was released and U.S. General Dwight D. Eisenhower finally accepted his self-nomination as high commissioner of North Africa and French West Africa, a move that enraged de Gaulle, who refused to recognise his status.

Henri Giraud, a general who had escaped from military captivity in Germany in April 1942, had negotiated with the Americans for leadership in the invasion. He arrived in Algiers on 10 November, and agreed to subordinate himself to Admiral Darlan as the commander of the French African army.[75]

Later that day Darlan ordered a ceasefire and Vichy French forces began, en masse, to join the Free French cause. Initially at least the effectiveness of these new recruits was hampered by a scarcity of weaponry and, among some of the officer class, a lack of conviction in their new cause.[74]

After the signing of the cease-fire, the Germans lost faith in the Vichy regime, and on 11 November 1942 German and Italian forces occupied Vichy France (Case Anton), violating the 1940 armistice, and triggering the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon on 27 November 1942. In response, the Vichy Army of Africa joined the Allied side. They fought in Tunisia for six months until April 1943, when they joined the campaign in Italy as part of the French Expeditionary Corps in Italy (FEC).

Admiral Darlan was assassinated on 24 December 1942 in Algiers by the young monarchist Bonnier de La Chapelle. Although de la Chapelle had been a member of the resistance group led by Henri d'Astier de La Vigerie, it is believed he was acting as an individual.

On 28 December, after a prolonged blockade, the Vichy forces in French Somaliland were ousted.

After these successes, Guadeloupe and Martinique in the West Indies—as well as French Guiana on the northern coast of South America—finally joined Free France in the first months of 1943. In November 1943, the French forces received enough military equipment through Lend-Lease to re-equip eight divisions and allow the return of borrowed British equipment.

Creation of the French Committee of National Liberation (CFLN)

The Vichy forces in North Africa had been under Darlan's command and had surrendered on his orders. The Allies recognised his self-nomination as High Commissioner of France (French military and civilian commander-in-chief, Commandement en chef français civil et militaire) for North and West Africa. He ordered them to cease resisting and co-operate with the Allies, which they did. By the time the Tunisia Campaign was fought, the ex-Vichy French forces in North Africa had been merged with the FFF.[76][77]

After Admiral Darlan's assassination, Giraud became his de facto successor in French Africa with Allied support. This occurred through a series of consultations between Giraud and de Gaulle. The latter wanted to pursue a political position in France and agreed to have Giraud as commander in chief, as the more qualified military person of the two. It is questionable that he ordered that many French resistance leaders who had helped Eisenhower's troops be arrested, without any protest by Roosevelt's representative, Robert Murphy.

Later, the Americans sent Jean Monnet to counsel Giraud and to press him into repeal the Vichy laws. The Cremieux decree, which granted French citizenship to Jews in Algeria and which had been repealed by Vichy, was immediately restored by General de Gaulle. Democratic rule was restored in French Algeria, and the Communists and Jews liberated from the concentration camps.[78]

Giraud took part in the Casablanca conference in January 1943 with Roosevelt, Churchill and de Gaulle. The Allies discussed their general strategy for the war, and recognised joint leadership of North Africa by Giraud and de Gaulle. Henri Giraud and Charles de Gaulle then became co-presidents of the French Committee of National Liberation (Comité Français de Libération Nationale, CFLN), which unified the territories controlled by them and was officially founded on 3 June 1943.

The CFLN set up a temporary French government in Algiers, raised more troops and re-organised, re-trained and re-equipped the Free French military, in co-operation with Allied forces in preparation of future operations against Italy and the German Atlantic wall.

Eastern Front

The Normandie-Niemen Regiment, founded at the suggestion of Charles de Gaulle, was a fighter regiment of the Free French Air Force that served on the Eastern Front of the European Theatre of World War II with the 1st Air Army. The regiment is notable for being the only air combat unit from an Allied western country to participate on the Eastern Front during World War II (except brief interventions from RAF and USAAF units) and the only one to fight together with the Soviets until the end of the war in Europe.

The unit was the GC3 (Groupe de Chasse 3 or 3rd Fighter Group) in the Free French Air Force, first commanded by Jean Tulasne. The unit originated in mid-1943 during World War II. Initially the groupe comprised a group of French fighter pilots sent to aid Soviet forces at the suggestion of Charles de Gaulle, leader of the Free French Forces, who felt it important that French servicemen serve on all fronts in the war. The regiment fought in three campaigns on behalf of the Soviet Union between 22 March 1943, and 9 May 1945, during which time it destroyed 273 enemy aircraft and received numerous orders, citations and decorations from both France and the Soviet Union, including the French Légion d'Honneur and the Soviet Order of the Red Banner. Joseph Stalin awarded the unit the name Niemen for its participation in the Battle of the Niemen River.

Tunisia, Italy and Corsica

The Free French forces participated in the Tunisian Campaign. Together with British and Commonwealth forces, the FFF advanced from the south while the formerly Vichy-loyal Army of Africa advanced from the west together with the Americans. The fighting in Tunisia ended with the Axis forces surrendering to the Allies in July 1943.

During the campaign in Italy during 1943–1944, a total of between 70,000[20] and 130,000 Free French soldiers fought on the Allied side. The French Expeditionary Corps consisted of 60% colonial soldiers, mostly Moroccans and 40% Europeans, mostly Pied-Noirs.[35] They took part in the fighting on the Winter Line and Gustav Line, distinguishing themselves at Monte Cassino in Operation Diadem.[79][80] In what came to be known as the Marocchinate in one of the worst mass atrocities committed by Allied troops during the war, the Moroccan Goumiers, raped and killed Italians civilians on a massive scale during those operations, often under the indifferent eye of their French officers, if not their encouragement.[81] Acts of violence by French troops against civilians continued even after the liberation of Rome.[82] French Marshal Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, claimed that such cases were isolated events exploited by German propaganda to smear allies, particularly French troops.[83]

In September 1943, the liberation of Corsica from Italian occupation began, after the Italian armistice, with the landing of elements of the reconstituted French I Corps (Operation Vesuvius).

Forces Françaises Combattantes and National Council of the Resistance

The French Resistance gradually grew in strength. General de Gaulle set a plan to bring together the fragmented groups under his leadership. He changed the name of his movement to "Fighting French Forces" (Forces Françaises Combattantes) and sent Jean Moulin back to France as his formal link to the irregulars throughout the occupied country to co-ordinate the eight major Résistance groups into one organisation. Moulin got their agreement to form the "National Council of the Resistance" (Conseil National de la Résistance). Moulin was eventually captured, and died under brutal torture by the Gestapo.

De Gaulle's influence had also grown in France, and in 1942 one resistance leader called him "the only possible leader for the France that fights".[84] Other Gaullists, those who could not leave France (that is, the overwhelming majority of them), remained in the territories ruled by Vichy and the Axis occupation forces, building networks of propagandists, spies and saboteurs to harass and discomfit the enemy.

Later, the Resistance was more formally referred to as the "French Forces of the Interior" (Forces Françaises de l'Intérieur, or FFI). From October 1944 – March 1945, many FFI units were amalgamated into the French Army to regularise the units.

Liberation of France

The liberation of continental France began on D-Day, 6 June 1944, with the invasion of Normandy, the amphibious assault aimed at establishing a bridgehead for the forces of Operation Overlord. At first hampered by very stiff German resistance and the bocage terrain of Normandy, the Allies broke out of Normandy at Avranches on 25–31 July 1944. Combined with the landings in Provence of Operation Dragoon on 14 August 1944, the threat of being caught in a pincer movement led to a very rapid German retreat, and by September 1944 most of France had been liberated.

Normandy and Provence landings

Opening a "Second Front" was a top priority for the Allies, and especially for the Soviets to relieve their burden on the Eastern Front. While Italy had been knocked out of the war in the Italian campaign in September 1943, the easily defensible terrain of the narrow peninsula required only a relatively limited number of German troops to protect and occupy their new puppet state in northern Italy. However, as the Dieppe raid had shown, assaulting the Atlantic Wall was not an endeavour to be taken lightly. It required extensive preparations such as the construction of artificial ports (Operation Mulberry) and an underwater pipeline across the English Channel (Operation Pluto), intensive bombardment of railways and German logistics in France (the Transportation Plan), and the wide-ranging military deception such as creating entire dummy armies like FUSAG (Operation Bodyguard) to make the Germans believe the invasion would take place where the Channel was at its narrowest.

By the time of the Normandy Invasion, the Free French forces numbered around 500,000 strong.[85] 900 Free French paratroopers landed as part of the British Special Air Service's (SAS) SAS Brigade; the 2e Division Blindée (2nd Armoured Division or 2e DB)—under General Leclerc—landed at Utah Beach in Normandy on 1 August 1944 together with other follow-on Free French forces, and eventually led the drive toward Paris.

In the battle for Caen, bitter fighting led to the almost total destruction of the city, and stalemated the Allies. They had more success in the western American sector of the front, where after the Operation Cobra breakthrough in late July they caught 50,000 Germans in the Falaise pocket.

The invasion was preceded by weeks of intense resistance activity. Coordinated with the massive bombardments of the Transportation Plan and supported by the SOE and the OSS, partisans systematically sabotaged railway lines, destroyed bridges, cut German supply lines, and provided general intelligence to the allied forces. The constant harassment took its toll on the German troops. Large remote areas were no-go zones for them and free zones for the maquisards so-called after the maquis shrubland that provided ideal terrain for guerrilla warfare. For instance, a large number of German units were required to clear the maquis du Vercors, which they eventually succeeded with, but this and numerous other actions behind German lines contributed to a much faster advance following the Provence landings than the Allied leadership had anticipated.

The main part of French Expeditionary Corps in Italy which had been fighting there was withdrawn from the Italian front, and added to the French First Army—under General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny—and joined the US 7th Army to form the US 6th Army Group. That was the force that conducted Operation Dragoon (also known as Operation Anvil), the Allied invasion of southern France. The objective of the French 2nd Corps was to capture ports at Toulon (France's largest naval port) and Marseilles (France's largest commercial port) in order to secure a vital supply line for the incoming troops. Most of the German troops there were second-line, consisting mainly of static and occupation units with a large number of Osttruppen volunteers, and with a single armoured division, the 11. Panzer-Division. The Allies sustained only relatively light casualties during the amphibious assault, and were soon in an all-out pursuit of a German army in full retreat along the Rhône valley and the Route Napoleon. Within 12 days the French forces were able to secure both ports, destroying two German Divisions in the process. Then on 12 September, French forces were able to connect to General George Patton's Third Army. Toulon and Marseille were soon providing supplies not only to the 6th Army Group but also to General Omar Bradley's 12th Army Group, which included Patton's Army. For its part, troops from de Lattre's French First Army were the first Allied troops to reach the Rhine.

While on the right flank the French liberation army was covering Alsace-Lorraine (and the Alpine front against German-occupied Italy), the centre was made up of US forces in the south (12th Army Group) and British and Commonwealth forces in the north (21st Army Group). On the left flank, Canadian forces cleared the Channel coast, taking Antwerp on 4 September 1944.

Liberation of Paris

After the failed 20 July plot against him, Hitler had given orders to have Paris destroyed should it fall to the Allies, similarly to the planned destruction of Warsaw.

Mindful of this and other strategic considerations, General Dwight D. Eisenhower was planning to by-pass the city. At this time, Parisians started a general strike on 15 August 1944 that escalated into a full-scale uprising of the FFI a few days later. As the Allied forces waited near Paris, de Gaulle and his Free French government put General Eisenhower under pressure. De Gaulle was furious about the delay and was unwilling to allow the people of Paris to be slaughtered as had happened in the Polish capital of Warsaw during the Warsaw uprising. De Gaulle ordered General Leclerc to attack single-handedly without the aid of Allied forces. Eventually, Eisenhower agreed to detach the 4th US Infantry Division in support of the French attack.

The Allied High Command (SHAEF) requested the Free French force in question to be all-white, if possible, but this was very difficult because of the large numbers of black West Africans in their ranks.[34] General Leclerc sent a small advance party to enter Paris, with the message that the 2e DB (composed of 10,500 French, 3,600 Maghrebis[86][87] and about 350 Spaniards[33] in the 9th company of the 3rd Battalion of the Régiment de Marche du Tchad made up mainly of Spanish Republican exiles[88]) would be there the following day. This party was commanded by Captain Raymond Dronne, and was given the honour to be the first Allied unit to enter Paris ahead of the 2e Division Blindée. The 1er Bataillon de Fusiliers-Marins Commandos formed from the Free French Navy Fusiliers-Marins that had landed on Sword Beach were also amongst the first of the Free French forces to enter Paris.

The military governor of the city, Dietrich von Choltitz, surrendered on 25 August, ignoring Hitler's orders to destroy the city and fight to the last man.[89] Jubilant crowds greeted the Liberation of Paris. French forces and de Gaulle conducted a now iconic parade through the city.

Provisional republic and the war against Germany and Japan

Re-establishment of a provisional French Republic and its government (GPRF)

The Provisional Government of the French Republic (gouvernement provisoire de la République Française or GPRF) was officially created by the CNFL and succeeded it on 3 June 1944, the day before de Gaulle arrived in London from Algiers on Churchill's invitation, and three days before D-Day. Its creation marked the re-establishment of France as a republic, and the official end of Free France. Among its most immediate concerns were to ensure that France did not come under allied military administration, preserving the sovereignty of France and freeing Allied troops for fighting on the front.

After the liberation of Paris on 25 August 1944, it moved back to the capital, establishing a new "national unanimity" government on 9 September 1944, including Gaullists, nationalists, socialists, communists and anarchists, and uniting the politically divided Resistance. Among its foreign policy goals was to secure a French occupation zone in Germany and a permanent UNSC seat. This was assured through a large military contribution on the western front.

Several alleged Vichy loyalists involved in the Milice (a paramilitary militia)—which was established by Sturmbannführer Joseph Darnand who hunted the Resistance with the Gestapo—were made prisoners in a post-liberation purge known as the épuration légale (legal purge or cleansing). Some were executed without trial, in "wild cleansings" (épuration sauvage). Women accused of "horizontal collaboration" because of alleged sexual relationships with Germans during the occupation were arrested and had their heads shaved, were publicly exhibited and some were allowed to be mauled by mobs.

On 17 August, Pierre Laval was taken to Belfort by the Germans. On 20 August, under German military escort, Pétain was forcibly moved to Belfort, and on 7 September to the Sigmaringen enclave in southern Germany, where 1,000 of his followers (including Louis-Ferdinand Céline) joined him. There they established a government in exile, challenging the legitimacy of de Gaulle's GPRF. As a sign of protest over his forced move, Pétain refused to take office, and was eventually replaced by Fernand de Brinon. The Vichy regime's exile ended when Free French forces reached the town and captured its members on 22 April 1945, the same day that the 3rd Algerian Infantry Division took Stuttgart. Laval, Vichy's prime minister in 1942–1944, was executed for treason. Pétain, "Chief of the French State" and hero of Verdun, was also condemned to death but his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment.

As the wartime government of France in 1944–1945, its main purposes were to handle the aftermath of the occupation of France and continue to wage war against Germany as a major Ally. It also made several important reforms and political decisions, such as granting women the right to vote, founding the École nationale d'administration, and laying the grounds of social security in France, and lasted until the establishment of the IVth Republic on 14 October 1946, preparing its new constitution.

Campaigns in France and Germany 1944–1945

.jpg.webp)

By September 1944, the Free French forces stood at 560,000 (including 176,500 White French from North Africa, 63,000 metropolitan French, 233,000 Maghrebis and 80,000 from Black Africa).[90][91] The GPRF set about raising new troops to participate in the advance to the Rhine and the invasion of Germany, using the FFI as military cadres and manpower pools of experienced fighters to allow a very large and rapid expansion of the French Liberation Army. It was well equipped and well supplied despite the economic disruption brought by the occupation thanks to Lend-Lease, and their number rose to 1 million by the end of the year. French forces were fighting in Alsace-Lorraine, the Alps, and besieging the heavily fortified French Atlantic coast submarine bases that remained Hitler-mandated stay-behind "fortresses" in ports along the Atlantic coast like La Rochelle and Saint-Nazaire until the German capitulation in May 1945.

Also in September 1944, the Allies having outrun their logistic tail (the "Red Ball Express"), the front stabilised along Belgium's northern and eastern borders and in Lorraine. From then on it moved at a slower pace, first to the Siegfried Line and then in the early months of 1945 to the Rhine in increments. For instance, the Ist Corps seized the Belfort Gap in a coup de main offensive in November 1944, their German opponents believing they had entrenched for the winter.

The French 2nd Armoured Division, tip of the spear of the Free French forces that had participated in the Normandy Campaign and liberated Paris, went on to liberate Strasbourg on 23 November 1944, thus fulfilling the Oath of Kufra made by its commanding officer General Leclerc almost four years earlier. The unit under his command, barely above company size when it had captured the Italian fort, had grown into a full-strength armoured division.

The spearhead of the Free French First Army that had landed in Provence was the Ist Corps. Its leading unit, the French 1st Armoured Division, was the first Western Allied unit to reach the Rhône (25 August 1944), the Rhine (19 November 1944) and the Danube (21 April 1945). On 22 April 1945, it captured Sigmaringen in Baden-Württemberg, where the last Vichy regime exiles, including Marshal Pétain, were hosted by the Germans in one of the ancestral castles of the Hohenzollern dynasty.

They participated in stopping Operation Nordwind, the very last German major offensive on the western front in January 1945, and in collapsing the Colmar Pocket in January–February 1945, capturing and destroying most of the German XIXth Army. Operations by the First Army in April 1945 encircled and captured the German XVIII SS Corps in the Black Forest, and cleared and occupied south-western Germany. At the end of the war, the motto of the French First Army was Rhin et Danube, referring to the two great German rivers that it had reached and crossed during its combat operations.

In May 1945, by the end of the war in Europe, the Free French forces comprised 1,300,000 personnel, and included around forty divisions making it the fourth largest Allied army in Europe behind the Soviet Union, the US and Britain.[92] The GPRF sent an expeditionary force to the Pacific to retake French Indochina from the Japanese, but Japan surrendered and Viet Minh took advantage by the successful August Revolution before they could arrive in theatre.

At that time, General Alphonse Juin was the chief of staff of the French army, but it was General François Sevez who represented France at Reims on 7 May, while General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny led the French delegation at Berlin on V-E day, as he was the commander of the French First Army. At the Yalta Conference, Germany had been divided into Soviet, American and British occupation zones, but France was then given an occupation zone in Germany, as well as in Austria and in the city of Berlin. It was not only the role that France played in the war which was recognised, but its important strategic position and significance in the Cold War as a major democratic, capitalist nation of Western Europe in holding back the influence of communism on the continent.

Approximately 58,000 men were killed fighting in the Free French forces between 1940 and 1945.[93]

World War II victory

A point of strong disagreement between de Gaulle and the Big Three (Roosevelt, Stalin and Churchill), was that the President of the Provisional Government of the French Republic (GPRF), established on 3 June 1944, was not recognised as the legitimate representative of France. Even though de Gaulle had been recognised as the leader of Free France by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill back on 28 June 1940, his GPRF presidency had not resulted from democratic elections. However, two months after the liberation of Paris and one month after the new "unanimity government", the Big Three recognised the GPRF on 23 October 1944.[94][95]

In his liberation of Paris speech, de Gaulle argued "It will not be enough that, with the help of our dear and admirable Allies, we have got rid of him [the Germans] from our home for us to be satisfied after what happened. We want to enter his territory as it should be, as victors", clearly showing his ambition that France be considered one of the World War II victors just like the Big Three. This perspective was not shared by the western Allies, as was demonstrated in the German Instrument of Surrender's First Act.[96] The French occupation zones in Germany and in West Berlin cemented this ambition.

Legacy

The Free French Memorial on Lyle Hill in Greenock, in western Scotland, in the shape of the Cross of Lorraine combined with an anchor, was raised by subscription as a memorial to sailors on the Free French Naval Forces vessels that sailed from the Firth of Clyde to take part in the Battle of the Atlantic.

The memorial is also associated, locally, with the memory of the French destroyer Maillé Brézé (1931) which sank at the Tail of the Bank.[97]

To this day, General de Gaulle's Appeal of 18 June 1940 remains one of the most famous speeches in French history.[98][99]

See also

- France during the Second World War

- Free French Air Force

- Bureau Central de Renseignements et d'Action, the intelligence service

- Normandie-Niemen, free French squadron fighting on the Eastern Front with the USSR's Red Air Force

- Maquis (World War II)

- List of networks and movements of the French Resistance

- France Forever

- Jacques de Sieyes[100]

- Roger E. Brunschwig

- Chant des Partisans

- Military history of France during World War II

- French colonial empire

- List of French possessions and colonies

- Danish collaborator trials

Notes

- August–September 1940

- Because French Algeria was long considered part of Metropolitan France by the 1940s, the Free French government once operating there considered itself to be physically seated within France proper, to the same extent as if it were located in European France, and not a government-in-exile.

References

Citations

- French India, New Caledonia/New Hebrides and French Polynesia, were totally dependent economically and for their communication on British and Australian goodwill and support for Vichy was not a realistic option. Jean-Marc Regnault and Ismet Kurtovitch, "Les ralliements du Pacifique en 1940. Entre légende gaulliste, enjeux stratégiques mondiaux et rivalités Londres/Vichy", Revue d'histoire moderne et contemporaine, vol. 49, No. 4 (Oct. – Dec., 2002), p. 84–86

- Stacey 2007, p. 373.

- "VRID Mémorial – Un site utilisant WordPress". www.vrid-memorial.com. Retrieved 6 June 2023.

- Horne, Alistair (1969). To Lose a Battle; France, 1940 (2007 ed.). Penguin. p. 604. ISBN 978-0141030654.

- Taylor, p.58

- Alexander, Martin (2007). "After Dunkirk: The French Army's Performance Against 'Case Red', 25 May to 25 June 1940". War in History. 14 (2): 226–227. doi:10.1177/0968344507075873. ISSN 1477-0385. S2CID 153751513.

- Jackson, Julian (2018). A Certain Idea of France: The Life of Charles de Gaulle. Allen Lane. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-1846143519.

- Horne, Alistair (1962). The Price of Glory; Verdun 1916 (1993 ed.). Penguin. p. 150. ISBN 978-0140170412.

- Munholland 2007, p. 10.

- Jackson, p. 110

- Jackson, p. 112

- Shlaim, Avi (July 1974). "Prelude to Downfall: The British Offer of Union to France, June 1940". Journal of Contemporary History. 3. 9 (3): 27–63. doi:10.1177/002200947400900302. JSTOR 260024. S2CID 159722519.

- "A Mesmerising Oratory", The Guardian, 29 April 2007.

- de Gaulle, Charles (28 April 2007). "The flame of French resistance". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 31 August 2013. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- Munholland 2007, p. 11.

- Jackson 2001, p. 31, 134–135.

- P. M. H. Bell, France and Britain 1900–1940: Entente & Estrangement, London, New York, 1996, p. 249

- Axelrod & Kingston, p. 373.

- bbm.org Archived 27 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 2012

- Pierre Goubert (20 November 1991). The Course of French History. Psychology Press. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-415-06671-6. Archived from the original on 27 May 2013. Retrieved 6 March 2011.

- Axelrod & Kingston, p. 362.

- Hastings, Max, p.80

- Hastings, Max, p.126

- Yapp, Peter, p. 235. The Travellers' Dictionary of Quotation. Retrieved October 2012

- "Le Domaine français de Sainte-Hélène" (in French). 13 November 2009. Retrieved 6 July 2019.

- Jennings, Eric T. Free French Africa in World War II. p. 66.

- Bennett, p. 16.

- History Learning Site Archived 3 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved October 2012

- Bennett, p. 13.

- Bennett, pp. 13–18.

- Hastings, Max, p. 74

- "Le bataillon d'infanterie de marine et du Pacifique". Museum of the Order of the Liberation. Archived from the original on 29 August 2018. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- Pierre Milza. Exils et migration: Italiens et Espagnols en France, 1938–1946, L'Harmattan, 1994, p. 590

- "Liberation of Paris: The hidden truth". The Independent. 31 January 2007. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2007.

- Paul Gaujac. Le Corps expéditionnaire français en Italie. Histoire et collections, 2003. p. 31

- Brahim Senouci, Préface de Stéphane Hessel. Algérie, une mémoire à vif: Ou le caméléon albinos. L'Harmattan, 2008, page 84

- Gilles Aubagnac. "Le retrait des troupes noires de la 1re Armée". Revue historique des armées, no 2, 1993, p. 34-46.

- Muracciole (2009), pp. 34–35.

- Crémieux-Brilhac (1996), p. 548.

- "Liste des volontaires des Forces françaises libres d'Henri Écochard". Archived from the original on 16 June 2011. Retrieved 5 December 2020..

- Muracciole (2009), p. 36.

- Voir les différentes évaluations des FFL Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- "Les Filles de la DB". www.marinettes-et-rochambelles.com. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- Pierre Clostermann, Une vie pas comme les autres, éd. Flammarion, 2005.

- www.france-libre.net, Le site de la France-Libre, "Les origines des FNFL, par l'amiral Thierry d'Argenlieu" Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine (in French)

- "The Cross of Lorraine from charles-de-gaulle.org". Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "War Memorials". Inverclyde Council. 9 August 2017. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Jordan, John and Robert Dumas (2009), French Battleships 1922–1956, p 77.

- Kappes, Irwin J. (2003) Mers-el-Kebir: A Battle Between Friends Archived 12 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Military History Online

- Hastings, Max, p.125

- (in French) Paul Vibert Archived 12 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine on ordredelaliberation.fr

- Hastings, Max, p. 125-126

- Munholland 2007, p. 14.

- Bimberg, Edward L. (2002). Tricolor Over the Sahara: The Desert Battles of the Free French, 1940–1942. Contributions in military studies (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 23–26. ISBN 9780313316548.

- Munholland 2007, p. 15.

- Jackson 2001, p. 391.

- Munholland 2007, p. 17.

- Keegan, John. Six Armies in Normandy. New York: Penguin Books, 1994. p300

- "The Second World War in the French Overseas Empire". Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2007.

- Munholland 2007, p. 19.

- Olson, James S., ed. (1991), Historical Dictionary of European Imperialism, Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, pp. 349–350

- Martin Thomas, "Deferring to Vichy in the Western Hemisphere: The St. Pierre and Miquelon Affair of 1941", International History Review (1997) 19#4 pp 809–835.online Archived 4 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- When the US wanted to take over France Archived 27 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Annie Lacroix-Riz, in Le Monde diplomatique, May 2003 (English, French, etc.)

- Taylor, p.93

- Mollo, p.144

- Hastings, Max, p. 81.

- Hastings, Max, p. 403.

- Hastings, Max, p.136

- Charles de Gaulle, Mémoires de guerre, édition La Pléiade, p. 260.

- Koch, Lutz, Rommel, (1950) ASIN B008DHD4LY

- Mellenthin, F. W. von (1971). Panzer battles : a study of the employment of armor in the Second World War. New York: Ballantine. p. 79. ISBN 0-345-32158-8. OCLC 14816982.

- Forczyk, Robert (2017). Case Red: The Collapse of France, 1940. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. p. 417. ISBN 978-1-4728-2442-4. OCLC 1002657539.

- Hastings, Max, p.375

- Hastings, Max, p.376

- Martin Thomas, "The Discarded Leader: General Henri Giraud and the Foundation of the French Committee of National Liberation", French History (1996) 10#12 pp. 86–111.

- Arthur L. Funk, "Negotiating the 'Deal with Darlan,'" Journal of Contemporary History (1973) 8#2 pp. 81–117. JSTOR 259995

- Arthur L. Funk, The Politics of Torch (1974)

- Extraits de l'entretien d'Annie Rey-Goldzeiguer [1, avec Christian Makarian et Dominique Simonnet, publié dans l'Express du 14 mars 2002 Archived 1 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, on the LDH website (in French)

- W. Clark, Mark (1950). Calculated Risk. Harper & Brothers. p. 348.

- "General Mark W. Clark". Monte Cassino Belvédère. Retrieved 29 March 2021.

- "The Anglo-Americans again pointed out that the behavior of the French troops caused the most serious difficulties: they were continuously receiving complaints about robberies and homicides, the authenticity of which could not be put in doubt" [...] For the essential, the American archives confirmed the accusations made by the Italian government [...] "The most extraordinary and painful aspect of this issue is the attitude of the French officers. Far from intervening to stop those crimes, they abused the civilian population which were trying to oppose such acts", Tommaso Baris Le corps expéditionnaire français en Italie. Violences des « libérateurs » durant l'été 1944, Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire Numéro 2007/1 (no 93), pp 47―61.

- Tommaso Baris: "Despite the Anglo-American command's request, acts of violence by French troops continued, even after the liberation of Rome"

- De Tassigny, Jean de Lattre (1985). Reconquérir: 1944-1945. Textes du maréchal Lattre de Tassigny réunis et présentés par Jean-Luc Barre [Reconquer: 1944-1945. Texts by Marshal Lattre de Tassigny collected and presented by Jean-Luc Barre] (in French). Éditions Plon. pp. 32–33.

- deRochemont, Richard (24 August 1942). "The French Underground". Life. p. 86. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- Axelrod, Alan; Kingston, Jack A. (2007). Encyclopedia of World War II, Volume 1. Facts on File Inc. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-8160-6022-1.

- Olivier Forcade, Du capitaine de Hauteclocque au Général Leclerc, Vingtième Siècle, Revue d'histoire, Année 1998, Volume 58, Numéro 58, pp. 144–146

- "Aspect méconnu de la composition de la 2e DB: en avril 1944, celle-ci comporte sur un effectif total de 14 490, une proportion de 25% de soldats nord-africains : 3 600", Christine Levisse-Touzé, Du capitaine de Hautecloque au général Leclerc?, Editions Complexe, 2000, p.243

- Mesquida, Evelyn (2011). La Nueve, 24 août 1944 : ces Républicains espagnols qui ont libéré Paris. Le Cherche Midi, 2011. ISBN 978-2-7491-2046-1.

- Hastings, Max, 557

- Muracciole (1996), p. 67.

- Benjamin Stora, " L'Armée d'Afrique : les oubliés de la libération ", TDC, no 692, 15 mars 1995, Paris, CNDP, 1995.

- Talbot, C. Imlay; Duffy Toft, Monica (24 January 2007). The Fog of Peace and War Planning: Military and Strategic Planning Under Uncertainty. Routledge, 2007. p. 227. ISBN 9781134210886.

- Sumner and Vauvillier 1998, p. 38

- 1940–1944 : La France Libre et la France Combattante pt. 2 Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in French). Charles de Gaulle foundation official website.

- 1940–1944 : La France Libre et la France Combattante pt. 1 Archived 16 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in French). Charles de Gaulle foundation official website.

- "France Excluded from the German Capitulation Signing by the Western Allies" Archived 29 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Reims Academy.

- Robert Jeffrey (6 November 2014). Scotland's Cruel Sea: Heroism and Disaster off the Scottish Coast. Black & White Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-84502-887-9.

- "Sarkozy Marks Anniversary of General de Gaulle's BBC Broadcast". BBC. 17 June 2010. Archived from the original on 19 October 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "Representations of the Second World War: Ideological Currents in French History (core.ac.uk)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 September 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- "AIDE IN U.S. LEAVES TO MEET DE GAULLE; Count de Sieyes Will Discuss How 'Free France' May Best Be Served Here". The New York Times. 20 February 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

Sources and further reading

- Axelrod, Alan; Kingston, Jack A. (2007). Encyclopedia of World War II. Vol. 1. Facts on File. ISBN 9780816060221.

- Bennett, G. H. (2011). The RAF's French Foreign Legion: De Gaulle, the British and the Re-emergence of French Airpower 1940-45. London; New York: Continuum. ISBN 9781441189783.

- Crémieux-Brilhac, Jean-Louis (1996). La France libre (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 2-07-073032-8.

- Gordon, Bertram M. Historical Dictionary of World War II France: The Occupation, Vichy, and the Resistance, 1938-1946 (1998)

- Hastings, Max (2011). All Hell Let Loose, The World at War 1939–45. London: Harper Press.

- Holland, James. Normandy '44: D-Day and the Epic 77-Day Battle for France (2019) 720pp

- Jackson, Julian (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820706-1. OCLC 1179786074.

- Mollo, Andrew (1981). The Armed Forces of World War II. Crown. ISBN 0-517-54478-4.

- Munholland, Kim (2007) [1970]. Arms, Men and Governments: The War Policies of Canada, 1939–1945. Queens Printer for Canada.

- Muracciole, Jean-François (1996). Histoire de la France libre. Que sais-je (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 978-2-13-047520-0.

- Muracciole, Jean-François (2009). Les Français libres. Histoires D'aujourd'hui (in French). Paris: Tallandier. ISBN 978-2-84-734596-4.

- Stacey, C.P. (2007) [2005]. Rock of Contention: Free French and Americans at War in New Caledonia, 1940–1945. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-84545-300-8.

- Sumner, Ian; Vauvillier, François (1998). The French Army 1939–45: Free French, Fighting French and the Army of Liberation. Men-at-arms Series No. 318. Vol. 2. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1855327078.

- Taylor, A. J. P. The Second World War – an Illustrated History, Hamish Hamilton, London, 1975.

External links

- Composition and situation of the Free French Force in combat

- Bibliography about 1st Free French Division

- FFF fighting units (France-Libre.net)

- Flags and Ensigns of Free France

- France-Libre.net (Free French Forces foundation)

- Fights of the population in Gers in the regular army from Nov.8, 1942 to Aug.31, 1944 (1992– O.N.A.C.- S.D. GERS translated in English)

- First Free French Division

.svg.png.webp)

_Cross_of_Lorraine.svg.png.webp)