Operation Torch

Operation Torch (8 November 1942 – 16 November 1942) was an Allied invasion of French North Africa during the Second World War.[5] Torch was a compromise operation that met the British objective of securing victory in North Africa while allowing American armed forces the opportunity to engage in the fight against Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy on a limited scale.[6] It was the first mass involvement of US troops in the European–North African Theatre, and saw the first major airborne assault carried out by the United States.

| Operation Torch | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the North African campaign of the Second World war | |||||||||

Landings during the operation | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

Ground forces: 107,000 troops 35,000 in Morocco 39,000 near Algiers 33,000 near Oran Naval activity: 108 aircraft 350 warships 500 transports Total: 850 |

Ground forces: 125,000 troops 210 tanks 500 aircraft many shore batteries and artillery pieces Naval activity: 1 battleship (partially armed) 10 other warships 11 submarines Germany: 14 submarines Italy: 14 submarines[2] | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

United States: 526 dead United Kingdom: 574 dead All Other Allies: 756 total wounded[3] 1 escort carrier (HMS Avenger) sunk with loss of 516 men 4 destroyers lost 2 sloops lost 6 troopships lost 1 minesweeper lost 1 auxiliary anti-aircraft ship lost |

Vichy France: 1,346+ dead 1,997 wounded several shore batteries destroyed all artillery pieces captured 1 light cruiser lost 5 destroyers lost 6 submarines lost 2 flotilla leaders lost Germany: 8 submarines lost by 17 November Italy: 2 submarines lost by 17 November[4] | ||||||||

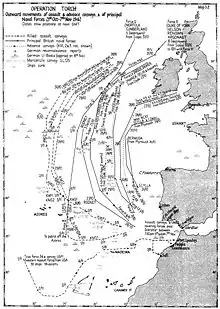

While the French colonies were formally aligned with Germany via Vichy France, the loyalties of the population were mixed. Reports indicated that they might support the Allies. American General Dwight D. Eisenhower, supreme commander of the Allied forces in Mediterranean Theater of Operations, planned a three-pronged attack on Casablanca (Western), Oran (Center) and Algiers (Eastern), then a rapid move on Tunis to catch Axis forces (Afrika Korps) in North Africa from the west in conjunction with Allied advances from Egypt.

Operation Torch's Western Task Force encountered unexpected resistance and bad weather, but Casablanca, the principal French Atlantic naval base, was captured after a short siege. The Center Task Force suffered some damage to its ships when trying to land in shallow water but the French ships were sunk or driven off; Oran surrendered after bombardment by British battleships. The French Resistance had successfully attempted a coup in Algiers and, even through the late alert raised in the Vichy forces, the Eastern Task Force met less opposition and were able to push inland and compel surrender on the first day.

The success of Torch caused Admiral François Darlan, commander of the Vichy French forces, who was in Algiers, to order co-operation with the Allies, in return for being installed as High Commissioner, with many other Vichy officials keeping their jobs. Darlan was assassinated soon afterwards, and the Free French gradually came to dominate the government.

Background

The Allies planned an Anglo-American invasion of French North Africa, the territories of Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia, nominally in the hands of the Vichy French government. With British forces advancing from Egypt, this would eventually allow the Allies to carry out a pincer operation against Axis forces in North Africa. The Vichy French had around 125,000 soldiers in the territories as well as coastal artillery, 210 operational but out-of-date tanks and about 500 aircraft, half of which were Dewoitine D.520 fighters—equal to many British and U.S. fighters.[7] These forces included 60,000 troops in Morocco, 15,000 in Tunisia, and 50,000 in Algeria, with coastal artillery, and a small number of tanks and aircraft.[8] In addition, there were 10 or so warships and 11 submarines at Casablanca.

Political situation on the ground

The Allies believed that the Vichy French Armistice Army would not fight, partly because of information supplied by the American Consul Robert Daniel Murphy in Algiers. The French were former members of the Allies and the American troops were instructed not to fire unless they were fired upon.[9] However, they harbored suspicions that the Vichy French Navy would bear a grudge over the actions of the British in June 1940 to prevent French ships being taken by the Germans; the attack on the French Navy in harbour at Mers-el-Kébir, near Oran, killed almost 1,300 French sailors.

An assessment of the sympathies of the French forces in North Africa was essential, and plans were made to secure their cooperation, rather than resistance. German support for the Vichy French came in the shape of air support. Several Luftwaffe bomber wings undertook anti-shipping strikes against Allied ports in Algiers and along the North African coast.

Operational command

The operation was originally scheduled to be led by General Joseph Stilwell, but he was reassigned after the Arcadia Conference revealed his vitriolic Anglophobia and skepticism over the operation.[10] Lt. General Dwight D. Eisenhower was given command of the operation, and he set up his headquarters in Gibraltar. The Allied Naval Commander of the Expeditionary Force was Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham; his deputy was Vice-Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, who planned the amphibious landings.

Strategic debate among the Allies

Senior U.S. commanders remained strongly opposed to the landings and after the western Allied Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) met in London on 30 July 1942, General George Marshall and Admiral Ernest King declined to approve the plan. Marshall and other U.S. generals advocated the invasion of northern Europe later that year, which the British rejected.[11][12] After Prime Minister Winston Churchill pressed for a landing in French North Africa in 1942, Marshall suggested instead to President Franklin D. Roosevelt that the U.S. abandon the Germany first strategy and take the offensive in the Pacific. Roosevelt said it would do nothing to help the Soviets.[13] With Marshall unable to persuade the British to change their minds,[14] President Roosevelt gave a direct order that Torch was to have precedence over other operations and was to take place at the earliest possible date, one of only two direct orders he gave to military commanders during the war.

In conducting their planning, Allied military strategists needed to consider the political situation on the ground in North Africa, which was complex, as well as external diplomatic political aspects. The Americans had recognized Pétain and the Vichy government in 1940, whereas the British did not and had recognized General Charles de Gaulle's French National Committee as a government-in-exile instead, and agreed to fund them. North Africa was part of France's colonial empire and nominally in support of Vichy, but that support was far from universal among the population.[15]

Political events on the ground contributed to, and in some cases were even primary over, military aspects. The French population in North Africa were divided into three groups:[15]

- Gaullists – De Gaulle was the rallying point for the French National Committee[lower-alpha 1] This comprised French refugees who escaped metropolitan France rather than succumb to the German occupation, or those who stayed and joined the French Resistance. One acolyte, General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, organized a fighting force and conducted raids in 1943 along a 1,600 miles (2,600 km) path from Lake Chad to Tripoli and joined with General Bernard Montgomery's British Eighth Army on 25 January 1943.[15]

- French Liberation Movement – some Frenchmen living in North Africa and operating in secret under German surveillance organized an underground "French Liberation Movement", whose aim was to liberate France. General Henri Giraud, recently escaped from Germany, later became its leader. The personal clash between de Gaulle and Giraud prevented the Free French Forces and the French Liberation Movement groups from unifying during the North African campaign (Torch).[15]

- Loyal pro-Vichy French – there were those who remained loyal to Marshal Philippe Pétain and believed collaboration with the Axis powers was the best method of ensuring the future of France. François Darlan was Pétain's designated successor.[15]

American strategy in planning the attack had to take into account these complexities on the ground. The planners assumed that if the leaders were given Allied military support they would take steps to liberate themselves, and the U.S. embarked on detailed negotiations under American Consul General Robert Murphy in Rabat with the French Liberation Movement. Since Britain was already diplomatically and financially committed to de Gaulle, it was clear that negotiations with the French Liberation Movement would have to be conducted by the Americans, and the invasion as well. Because of divided loyalties among the groups on the ground their support was uncertain, and due to the need to maintain secrecy, detailed plans could not be shared with the French.[15]

Allied plans

Planners identified Oran, Algiers and Casablanca as key targets. Ideally there would also be a landing at Tunis to secure Tunisia and facilitate the rapid interdiction of supplies traveling via Tripoli to Erwin Rommel's Afrika Korps forces in Italian Libya. However, Tunis was much too close to the Axis airfields in Sicily and Sardinia for any hope of success. A compromise would be to land at Bône in eastern Algeria, some 300 miles (480 km) closer to Tunis than Algiers. Limited resources dictated that the Allies could only make three landings and Eisenhower—who believed that any plan must include landings at Oran and Algiers—had two main options: either the western option, to land at Casablanca, Oran and Algiers and then make as rapid a move as possible to Tunis some 500 miles (800 km) east of Algiers once the Vichy opposition was suppressed; or the eastern option, to land at Oran, Algiers and Bône and then advance overland to Casablanca some 500 miles (800 km) west of Oran. He favored the eastern option because of the advantages it gave to an early capture of Tunis and also because the Atlantic swells off Casablanca presented considerably greater risks to an amphibious landing there than would be encountered in the Mediterranean.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff, however, were concerned that should Operation Torch precipitate Spain to abandon neutrality and join the Axis, the Straits of Gibraltar could be closed cutting the entire Allied force's lines of communication. They therefore chose the Casablanca option as the less risky since the forces in Algeria and Tunisia could be supplied overland from Casablanca (albeit with considerable difficulty) in the event of closure of the straits.[16]

Marshall's opposition to Torch delayed the landings by almost a month, and his opposition to landings in Algeria led British military leaders to question his strategic ability; the Royal Navy controlled the Strait of Gibraltar, and Spain was unlikely to intervene as Francisco Franco was hedging his bets. The Morocco landings ruled out the early occupation of Tunisia. Marshall did convince the Allies to abandon the planned invasions of Madeira and Tangier in preparation for the landings, which he maintained would lose the element of surprise and draw large Spanish military contingents in Spanish Morocco and the Canary Islands into the war. However, Harry Hopkins convinced President Franklin D. Roosevelt to agree to the general plan.[17] Eisenhower told Patton that the past six weeks were the most trying of his life.[18] In Eisenhower's acceptance of landings in Algeria and Morocco, he pointed out that the decision removed the early capture of Tunis from the probable to only the remotely possible because of the extra time it would afford the Axis to move forces into Tunisia.[19]

Intelligence gathering

In July 1941, Mieczysław Słowikowski (using the codename "Rygor"—Polish for "Rigor") set up "Agency Africa", one of the Second World War's most successful intelligence organizations.[20] His Polish allies in these endeavors included Lt. Col. Gwido Langer and Major Maksymilian Ciężki. The information gathered by the Agency was used by the Americans and British in planning the amphibious November 1942 Operation Torch[21][22] landings in North Africa.

Preliminary contact with Vichy French

To gauge the feeling of the Vichy French forces, Murphy was appointed to the American consulate in Algeria. His covert mission was to determine the mood of the French forces and to make contact with elements that might support an Allied invasion. He succeeded in contacting several French officers, including General Charles Mast, the French commander-in-chief in Algiers.

These officers were willing to support the Allies but asked for a clandestine conference with a senior Allied General in Algeria. Major General Mark W. Clark—one of Eisenhower's senior commanders—was dispatched to Cherchell in Algeria aboard the British submarine HMS Seraph and met with these Vichy French officers on 21 October 1942.

With help from the Resistance, the Allies also succeeded in slipping French General Henri Giraud out of Vichy France on HMS Seraph—passing itself off as an American submarine[23]—to Gibraltar, where Eisenhower had his headquarters, intending to offer him the post of commander in chief of French forces in North Africa after the invasion. However, Giraud would take no position lower than commander in chief of all the invading forces, a job already given to Eisenhower.[24] When he was refused, he decided to remain "a spectator in this affair".[25]

Battle

The Allies organised three amphibious task forces to simultaneously seize the key ports and airports in Morocco and Algeria, targeting Casablanca, Oran and Algiers. Successful completion of these operations was to be followed by an eastwards advance into Tunisia.

A Western Task Force (aimed at Casablanca) was composed of American units, with Major General George S. Patton in command and Rear Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt heading the naval operations. This Western Task Force consisted of the U.S. 3rd and 9th Infantry Divisions, and two battalions from the U.S. 2nd Armored Division—35,000 troops in a convoy of over 100 ships. They were transported directly from the United States in the first of a new series of UG convoys providing logistic support for the North African campaign.[26]

The Center Task Force, aimed at Oran, included the U.S. 2nd Battalion 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, the U.S. 1st Infantry Division, and the U.S. 1st Armored Division—a total of 18,500 troops. They sailed from the United Kingdom and were commanded by Major General Lloyd Fredendall, the naval forces being commanded by Commodore Thomas Troubridge.

Torch was, for propaganda purposes, a landing by U.S. forces, supported by British warships and aircraft, under the belief that this would be more palatable to French public opinion, than an Anglo-American invasion. For the same reason, Churchill suggested that British soldiers might wear U.S. Army uniforms, and No.6 Commando did so.[27] (Fleet Air Arm aircraft did carry US "star" roundels during the operation,[28] and two British destroyers flew the Stars and Stripes.[27]) In reality, the Eastern Task Force—aimed at Algiers—was commanded by Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson and consisted of a brigade from the British 78th and the U.S. 34th Infantry Divisions, along with two British commando units (No. 1 and No. 6 Commandos), together with the RAF Regiment providing 5 squadrons of infantry and 5 Light anti-aircraft flights, totalling 20,000 troops. During the landing phase, ground forces were to be commanded by U.S. Major General Charles W. Ryder, Commanding General (CG) of the 34th Division and naval forces were commanded by Royal Navy Vice-Admiral Sir Harold Burrough.

U-boats, operating in the eastern Atlantic area crossed by the invasion convoys, had been drawn away to attack trade convoy SL 125.[29] Aerial operations were split into two commands, with Royal Air Force aircraft under Air Marshal Sir William Welsh operating east of Cape Tenez in Algeria, and all United States Army Air Forces aircraft under Major General Jimmy Doolittle, who was under the direct command of Major General Patton, operating west of Cape Tenez. P-40s of the 33rd Fighter Group were launched from U.S. Navy escort carriers and landed at Port Lyautey on 10 November. Additional air support was provided by the carrier USS Ranger, whose squadrons intercepted Vichy aircraft and bombed hostile ships.

Casablanca

.jpg.webp)

The Western Task Force landed before daybreak on 8 November 1942, at three points in Morocco: Safi (Operation Blackstone), Fedala (Operation Brushwood, the largest landing with 19,000 men), and Mehdiya-Port Lyautey (Operation Goalpost). Because it was hoped that the French would not resist, there were no preliminary bombardments. This proved to be a costly error as French defenses took a toll on American landing forces. On the night of 7 November, pro-Allied General Antoine Béthouart attempted a coup d'etat against the French command in Morocco, so that he could surrender to the Allies the next day. His forces surrounded the villa of General Charles Noguès, the Vichy-loyal high commissioner. However, Noguès telephoned loyal forces, who stopped the coup. In addition, the coup attempt alerted Noguès to the impending Allied invasion, and he immediately bolstered French coastal defenses.

At Fedala, a small port with a large beach close to Casablanca, weather disrupted the landings. The landing beaches again came under French fire after daybreak. Patton landed at 08:00, and the beachheads were secured later in the day. The Americans surrounded the port of Casablanca by 10 November, and the city surrendered an hour before the final assault was due to take place. Casablanca was the principal French Atlantic naval base after German occupation of the European coast. The Naval Battle of Casablanca resulted from a sortie of French cruisers, destroyers, and submarines opposing the landings. A cruiser, six destroyers, and six submarines were destroyed by American gunfire and aircraft. The incomplete French battleship Jean Bart—which was docked and immobile—fired on the landing force with her one working gun turret until disabled by the 16-inch calibre American naval gunfire of USS Massachusetts, the first such heavy-calibre shells fired by the U.S. Navy anywhere in World War II. Many of her one ton shells didn't explode, linked to poor detonators, and aircraft bombers sank the Jean Bart.[30] Two U.S. destroyers were damaged.

At Safi, the objective being capturing the port facilities to land the Western Task Force's medium tanks, the landings were mostly successful.[31] The landings were begun without covering fire, in the hope that the French would not resist at all. However, once French coastal batteries opened fire, Allied warships returned fire. By the time the 3rd Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment arrived, French snipers had pinned the assault troops (most of whom were in combat for the first time) on Safi's beaches. Most of the landings occurred behind schedule. Carrier aircraft destroyed a French truck convoy bringing reinforcements to the beach defenses. Safi surrendered on the afternoon of 8 November. By 10 November, the remaining defenders were pinned down, and the bulk of Harmon's forces raced to join the siege of Casablanca.

At Port-Lyautey, the landing troops were uncertain of their position, and the second wave was delayed. This gave the French defenders time to organize resistance, and the remaining landings were conducted under artillery bombardment. A former French pilot of the port on board a US destroyer led her up the shallow river to take over the artillery battery, clearing the way to the air-base. With the assistance of carrier air support, the troops pushed ahead, and the objectives were captured.

Oran

The Center Task Force was split between three beaches, two west of Oran and one east. Landings at the westernmost beach were delayed because of a French convoy which appeared while the minesweepers were clearing a path. Some delay and confusion, and damage to landing ships, was caused by the unexpected shallowness of water and sandbars; although periscope observations had been carried out, no reconnaissance parties had landed on the beaches to determine the local maritime conditions. This helped inform subsequent amphibious assaults—such as Operation Overlord—in which considerable weight was given to pre-invasion reconnaissance.

The U.S. 1st Ranger Battalion landed east of Oran and quickly captured the shore battery at Arzew. An attempt was made to land U.S. infantry at the harbour directly, in order to quickly prevent destruction of the port facilities and scuttling of ships. Operation Reservist failed, as the two Banff-class sloops were destroyed by crossfire from the French vessels there. The Vichy French naval fleet broke from the harbor and attacked the Allied invasion fleet but its ships were all sunk or driven ashore.[32] The commander of Reservist, Captain Frederick Thornton Peters, was awarded the Victoria Cross for valour in pushing the attack through Oran harbour in the face of point blank fire.[lower-alpha 2][33] French batteries and the invasion fleet exchanged fire throughout 8–9 November, with French troops defending Oran and the surrounding area stubbornly; bombardment by the British battleships brought about Oran's surrender on 10 November.

Airborne landings

Torch was the first major airborne assault carried out by the United States. The 2nd Battalion, 509th Parachute Infantry Regiment, aboard 39 C-47 Dakotas, flew all the way from Cornwall in England, over Spain, to drop near Oran and capture airfields at Tafraoui and La Sénia, respectively 15 miles (24 km) and 5 miles (8 km) south of Oran.[34] The operation was marked by communicational and navigational problems owing to the anti-aircraft and beacon ship HMS Alynbank broadcasting on the wrong frequency.[35] Poor weather over Spain and the extreme range caused the formation to scatter and forced 30 of the 37 air transports to land in the dry salt lake to the west of the objective.[36] Of the other aircraft, one pilot became disoriented and landed his plane in Gibraltar. Two others landed in French Morocco and three in Spanish Morocco, where another Dakota dropped its paratroopers by mistake. A total of 67 American troops were interned by Franco's forces until February 1943. Tafraoui and La Sénia were eventually captured but the role played by the airborne forces in Operation Torch was minimal.[35][37]

Algiers

Resistance and coup

As agreed at Cherchell, in the early hours of 8 November, the 400 mainly Jewish French Resistance fighters of the Géo Gras Group staged a coup in the city of Algiers.[38] Starting at midnight, the force under the command of Henri d'Astier de la Vigerie and José Aboulker seized key targets, including the telephone exchange, radio station, governor's house and the headquarters of the 19th Corps.

Robert Murphy took some men and then drove to the residence of General Alphonse Juin, the senior French Army officer in North Africa. While they surrounded his house (making Juin a hostage) Murphy attempted to persuade him to side with the Allies. Juin was treated to a surprise: Admiral François Darlan—the commander of all French forces—was also in Algiers on a private visit. Juin insisted on contacting Darlan and Murphy was unable to persuade either to side with the Allies. In the early morning, the local Gendarmerie arrived and released Juin and Darlan.

Invasion

On 8 November 1942, the invasion commenced with landings on three beaches—two west of Algiers and one east. The landing forces were under the overall command of Major-General Charles W. Ryder, commanding general of the U.S. 34th Infantry Division. The 11th Brigade Group from the British 78th Infantry Division landed on the right hand beach; the US 168th Regimental Combat Team, from the 34th Infantry Division, supported by 6 Commando and most of 1 Commando, landed on the middle beach; and the US 39th Regimental Combat Team, from the US 9th Infantry Division, supported by the remaining 5 troops from 1 Commando, landed on the left hand beach. The 36th Brigade Group from the British 78th Infantry Division stood by in floating reserve.[39] Though some landings went to the wrong beaches, this was immaterial because of the lack of French opposition. All the coastal batteries had been neutralized by the French Resistance and one French commander defected to the Allies. The only fighting took place in the port of Algiers, where in Operation Terminal, two British destroyers attempted to land a party of US Army Rangers directly onto the dock, to prevent the French destroying the port facilities and scuttling their ships. Heavy artillery fire prevented one destroyer from landing but the other was able to disembark 250 Rangers before it too was driven back to sea.[32] The US troops pushed quickly inland and General Juin surrendered the city to the Allies at 18:00.

Aftermath

Political results

It quickly became clear that Giraud lacked the authority to take command of the French forces. He preferred to wait in Gibraltar for the results of the landing. However, Darlan in Algiers had such authority. Eisenhower, with the support of Roosevelt and Churchill, made an agreement with Darlan, recognizing him as French "High Commissioner" in North Africa. In return, Darlan ordered all French forces in North Africa to cease resistance to the Allies and to cooperate instead. The deal was made on 10 November, and French resistance ceased almost at once. The French troops in North Africa who were not already captured submitted to and eventually joined the Allied forces.[40] Men from French North Africa would see much combat under the Allied banner as part of the French Expeditionary Corps (consisting of 112,000 troops in April 1944) in the Italian campaign, where Maghrebis (mostly Moroccans) made up over 60% of the unit's soldiers.[41]

When Adolf Hitler learned of Darlan's deal with the Allies, he immediately ordered the occupation of Vichy France and sent Wehrmacht troops to Tunisia. The American press protested, immediately dubbing it the "Darlan Deal", pointing out that Roosevelt had made a brazen bargain with Hitler's puppets in France. If a main goal of Torch had originally been the liberation of North Africa, hours later that had been jettisoned in favor of safe passage through North Africa. Giraud ended up taking over the post when Darlan was assassinated six weeks later.[42]

The Eisenhower/Darlan agreement meant that the officials appointed by the Vichy regime would remain in power in North Africa. No role was provided for Free France, which was supposed to be France's government-in-exile and had taken charge in other French colonies. That deeply offended Charles de Gaulle, the head of Free France. It also offended much of the British and American public, who regarded all Vichy French as Nazi collaborators and Darlan as one of the worst. Eisenhower insisted, however, that he had no real choice if his forces were to move on against the Axis in Tunisia, rather than fight the French in Algeria and Morocco.

Though de Gaulle had no official power in Vichy North Africa, much of its population now publicly declared Free French allegiance, putting pressure on Darlan. On 24 December, Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle, a French resistance fighter and anti-fascist monarchist, assassinated Darlan. (Bonnier de La Chapelle was arrested on the spot and executed two days later.)

Giraud succeeded Darlan but, like him, replaced few of the Vichy officials. He even ordered the arrest of the leaders of the Algiers coup of 8 November, with no opposition from Murphy.

The French North African government gradually became active in the Allied war effort. The limited French troops in Tunisia did not resist German troops arriving by air; Admiral Esteva, the commander, obeyed orders to that effect from Vichy. The Germans took the airfields there and brought in more troops. The French troops withdrew to the west and, within a few days, began to skirmish against the Germans, encouraged by small American and British detachments who had reached the area. While that was of minimal military effect, it committed the French to the Allied side. Later, all French forces were withdrawn from action and properly reequipped by the Allies.

Giraud supported that but also preferred to maintain the old Vichy administration in North Africa. Under pressure from the Allies and de Gaulle's supporters, the French régime shifted, with Vichy officials gradually replaced and its more offensive decrees rescinded. In June 1943, Giraud and de Gaulle agreed to form the French Committee of National Liberation (CFLN), with members from both the North African government and from de Gaulle's French National Committee. In November 1943, de Gaulle became head of the CFLN and de jure head of government of France and was recognized by the U.S. and Britain.

In another political outcome of Torch (and at Darlan's orders), the previously-Vichyite government of French West Africa joined the Allies.

Toulon

One of the terms of the Second Armistice at Compiègne agreed to by the Germans was that the "zone libre" of southern France would remain free of German occupation and governed by Vichy. The lack of determined resistance by the Vichy French to the Allied invasions of North Africa and the new policies of de Gaulle in North Africa convinced the Germans that France could not be trusted. Moreover, the Anglo-American presence in French North Africa invalidated the only real rationale for not occupying the whole of France since it was the only practical means to deny the Allies use of the French colonies. The Germans and the Italians immediately occupied southern France, and the German Army moved to seize the French fleet in the port of Toulon from 10 November. The naval strength of the Axis in the Mediterranean would have been greatly increased if the Germans had succeeded in seizing the French ships, but every important ship was scuttled at dock by the French Navy before the Germans could take them.

Tunisia

After the German and Italian occupation of Vichy France and their failed attempt to capture the French fleet at Toulon (Operation Lila), the French Armée d'Afrique sided with the Allies, providing a third corps (XIX Corps) for Anderson. Elsewhere, French warships, such as the battleship Richelieu, rejoined the Allies.

On 9 November, Axis forces started to build up in French Tunisia, unopposed by the local French forces under General Barré. Wracked with indecision, Barré moved his troops into the hills and formed a defensive line from Teboursouk through Medjez el Bab and ordered that anyone trying to pass through the line would be shot. On 19 November, the German commander, Walter Nehring, demanded passage for his troops across the bridge at Medjez and was refused. The Germans attacked the poorly-equipped French units twice and were driven back. The French had suffered many casualties and lacking artillery and armour, Barré was forced to withdraw.[43]

After consolidating in Algeria, the Allies began the Tunisia Campaign. Elements of the First Army (Lieutenant-General Kenneth Anderson), came to within 40 mi (64 km) of Tunis before a counterattack at Djedeida thrust them back. In January 1943, German and Italian troops under Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, retreating westward from Libya, reached Tunisia.

The Eighth Army (Lieutenant-General Bernard Montgomery) advancing from the east, stopped around Tripoli while the port was repaired to disembark reinforcements and build up the Allied advantage. In the west, the forces of the First Army came under attack at the end of January, were forced back from the Faïd Pass and suffered a reversal at the Battle of Sidi Bou Zid on 14–15 February. Axis forces pushed on to Sbeitla and then fought the Battle of Kasserine Pass on 19 February, where the US II Corps retreated in disarray until Allied reinforcements halted the Axis advance on 22 February. Fredendall was sacked and replaced by George Patton.

General Sir Harold Alexander arrived in Tunisia in late February to take charge of the new 18th Army Group headquarters, which had been created to command the Eighth Army and the Allied forces already fighting in Tunisia. The Axis forces attacked eastward at the Battle of Medenine on 6 March but were easily repulsed by the Eighth Army. Rommel advised Hitler to allow a full retreat to a defensible line but was denied and on 9 March, Rommel left Tunisia to be replaced by Jürgen von Arnim, who had to spread his forces over 100 mi (160 km) of northern Tunisia.

The setbacks at Kasserine forced the Allies to consolidate their forces, develop their lines of communication and administration before another offensive. The First and Eighth Armies attacked again in April. Hard fighting followed but the Allies cut off the Germans and Italians from support by naval and air forces between Tunisia and Sicily. On 6 May, as the culmination of Operation Vulcan, the British took Tunis and American forces reached Bizerte. By 13 May, the Axis forces in Tunisia had surrendered, opening the way for the Allied invasion of Sicily in July.

Later influence

Despite Operation Torch's role in the war and logistical success, it has been largely overlooked in many popular histories of the war and in general cultural influence.[44] The Economist speculated that this was because French forces were the initial enemies of the landing, making for a difficult fit into the war's overall narrative in general histories.[44]

The operation was America's first armed deployment in the Arab world since the Barbary Wars and, according to The Economist, laid the foundations for America's postwar Middle East policy.[44]

Orders of battle

Western Task Force – Morocco

Vice Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, USN[45]

![]() US I Armored Corps

US I Armored Corps

Major General George S. Patton, USA

- Northern Attack Group (Mehedia)

- Brig. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott (9,099 officers and enlisted)

- 60th Infantry Regiment (Reinforced) of 9th Infantry Division

- 1st Battalion of 66th Armored Regiment of 2nd Armored Division

- 1st Battalion of 540th Engineers

- Center Attack Group (Fedhala)

- Maj. Gen. J. W. Anderson (18,783 officers and enlisted)

- Southern Attack Group (Safi)

- Maj. Gen. Ernest N. Harmon (6,423 officers and enlisted)

- 47th Regimental Combat Team of 9th Infantry Division

- 3rd and elements of 2nd Battalion of 67th Armored Regiment of 2nd Armored Division

![]() French Army in Morocco

French Army in Morocco

- Fez Division (Maj. Gen. Maurice-Marie Salbert)

- 4th Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- 5th Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- 11th Algerian Rifle Regiment

- 1st Foreign Cavalry Regiment

- Meknès Division (Maj. Gen. Andre-Marie-François Dody)

- 7th Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- 8th Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- 3rd Moroccan Spahis Regiment

- Casablanca Division (Brig. Gen. Antoine Béthouart)

- 1st Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- 6th Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- Colonial Moroccan Infantry Regiment

- 1st Hunters of Africa Regiment

- Marrakech Division (Brig. Gen. Henry Jules Jean Maurice Martin)

- 2nd Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- 2nd Foreign infantry Regiment

- 4th Moroccan Spahis Regiment

Central Task Force – Oran

Commodore Thomas Hope Troubridge, RN[46]

![]() US II Corps

US II Corps

Major General Lloyd R. Fredendall, USA

Approx. 39,000 officers and enlisted

- 1st Infantry "Big Red One" Division (Maj. Gen. Terry Allen)

- 1st Armored Division (Maj. Gen. Orlando Ward)

- Combat Command B

- 6th Armored Infantry Regiment

- 1st Ranger Battalion

![]() French Army in Algeria

French Army in Algeria

- Algiers Division (Maj. Gen. Charles Mast)

- 1st Algerian Rifle Regiment

- 9th Algerian Rifle Regiment

- 3rd Zouaves Regiment

- 2nd Hunters of Africa Regiment

- 1st Algerian Spahis Regiment

- Oran Division (Maj. Gen. Robert Boissau)

- 2nd Algerian Rifle Regiment

- 6th Algerian Rifle Regiment

- 15th Senegalese Rifle Regiment

- 1st Foreign Regiment

- Moroccan Division

- 7th Moroccan Rifle Regiment

- 3rd Algerian Rifle Regiment

- 4th Tunisian Rifle Regiment

- 3rd Foreign Rifle Regiment

Eastern Task Force – Algiers

Rear Admiral Sir Harold Burrough, RN[47]

Allied Landing Forces

Major General Charles W. Ryder, USA[lower-alpha 3]

Approx. 33,000 officers and enlisted

British (approx. 23,000)

British (approx. 23,000)

- 78th Infantry Division (Maj. Gen. Vyvyan Evelegh)

- No. 1 Commando

- No. 6 Commando

- 5 squadrons of RAF Regiment

.svg.png.webp) United States (approx. 10,000)

United States (approx. 10,000)

See also

- List of British military equipment of World War II

- List of French military equipment of World War II

- List of World War II Battles

- Mieczysław Zygfryd Słowikowski

- RMS Mooltan Troopship

- North African campaign timeline

- Operation Flagpole (World War II)

- Operation Husky

- Operation Kingpin (World War II)

- 17th Armored Engineer Battalion

- Marching Regiment of the Foreign Legion

- Atlantic Theater aircraft carrier operations during World War II#Allied Invasion of North Africa (1942)

- US Naval Bases North Africa

Notes

- also known as the "Free French", later, per de Gaulle's appellation, the "Fighting French").

- The award was posthumously as he was killed in an aircraft crash returning to the UK

- CG, US 34th Infantry Division

Citations

- Opération Torch – Les débarquements alliés en Afrique du Nord

- I sommergibili dell'Asse e l'Operazione Torch.

- Atkinson 2002, p. 159.

- Granito and Emo. Navi militari perdute, Italian Navy Historical Branch, pp. 61–62.

- Walker, David A. (1987). "OSS and Operation Torch". Journal of Contemporary History. 22 (4): 667–79. doi:10.1177/002200948702200406. ISSN 0022-0094. JSTOR 260815. S2CID 159522532. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 28 September 2020.

- Willmott 1984.

- Watson 2007, p. 50.

- ""The Stamford Historical Society Presents: Operation Torch and the Invasion of North Africa"". Archived from the original on 4 September 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2015.

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 126, 141–42.

- Roberts, Andrew (2009). Masters and Commanders: The Military Geniuses Who Led the West to Victory in World War II (1 ed.). London: Penguin Books. pp. 82–84. ISBN 978-0-141-02926-9 – via Archive Foundation.

- Husen (1999). Zabecki, David T.; Schuster, Carl O.; Rose, Paul J.; Van, William H. (eds.). World War II in Europe : an encyclopedia. Garland Pub. p. 1270. ISBN 9780824070298. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Mackenzie, S.P. (2014). The Second World War in Europe: Second Edition. Routledge. pp. 54–55. ISBN 978-1317864714. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Ward, Geoffrey C.; Burns, Ken (2014). "The Common Cause: 1939–1944". The Roosevelts: An Intimate History. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 402. ISBN 978-0385353069. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Routledge Handbook of US Military and Diplomatic History. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. 2013. p. 135. ISBN 9781135071028.

- United States Military Academy. Department of Military Art and Engineering (1947). The War in North Africa Part 2 – The Allied Invasion. West Point, NY: Department of Military Art and Engineering, United States Military Academy. pp. 4–5. Archived from the original on 3 February 2023. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- Eisenhower 1948, pp. 88–89.

- Roberts, Andrew (2009). Masters and Commanders: The Military Geniuses Who Led the West to Victory in World War II (1 ed.). London: Penguin Books. pp. 84–86. ISBN 978-0-141-02926-9 – via Archive Foundation.

- Smith, Jean Edward (2012). Eisenhower in War and Peace. New York: Random House. pp. 214–15. ISBN 9780679644293.

- Eisenhower 1948, p. 90.

- Stirling, Tessa; et al. (2005). Intelligence Co-operation between Poland and Great Britain during World War II. Vol. I: The Report of the Anglo-Polish Historical Committee. London: Vallentine Mitchell.

- Churchill 1951b, p. 643.

- Slowikowski, Rygor (1988). In the Secret Service: The Lightning of the Torch. London: The Windrush Press. p. 285.

- Churchill 1951a, p. 544.

- Groom 2006, p. 354.

- Atkinson 2002, p. 66.

- Hague 2000, pp. 179–80.

- Mangold, Peter (2012). Britain and the Defeated French: From Occupation to Liberation, 1940–1944. London: I.B. Tauris. p. 159.

- Brown 1968, p. 93.

- Edwards 1999, p. 115.

- Dumas, Robert (2001). Le cuirassé Jean Bart 1939–1970 [The Battleship Jean Bart 1939–1970] (in French). Rennes: Marine Éditions. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-2-909675-75-6.

- Howe 1993, pp. 97, 102.

- Rohwer & Hummelchen 1992, p. 175

- "Frederick Thornton Peters – the Canadian Virtual War Memorial – Veterans Affairs Canada". 20 February 2019.

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 146–47, map 19.

- Lane Herder, Brian (2017). Operation Torch 1942: The invasion of French North Africa. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 42. ISBN 9781472820556.

- Playfair et al. 2004, p. 149.

- Haskew, Michael E. (2017). The Airborne in World War II: An Illustrated History of America's. McMillan. p. 44. ISBN 9781250124470.

- Documentary film presenting the dominant role of Jewish resistance fighters in Algiers

- Playfair et al. 2004, pp. 126, 140–41, map 18.

- Eisenhower 1948, pp. 99–105, 107–10.

- Gaujac, Paul (2003). Le Corps expéditionnaire français en Italie (in French). Histoire et collections. p. 31.

- Satloff, Robert (9 October 2017). "Operation Torch and the Birth of American Middle East Policy, 75 Years On". Washington D.C.: Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Watson 2007, p. 60.

- R.B.S. (9 November 2017). "Remembering Operation Torch on its 75th anniversary". The Economist. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- Morison 1947, pp. 36–39.

- Morison 1947, p. 223.

- Morison 1947, p. 190.

Bibliography

- Allen, Bruce (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Stackpole Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6.

- Anderson, Charles R. (1993). Algeria-French Morocco 8 November 1942 – 11 November 1942. WWII Campaigns. Washington: United States Army Center of Military History. ISBN 0-16-038105-3. CMH Pub 72-11. Archived from the original on 5 April 2009. Retrieved 9 June 2010.

- Atkinson, Rick (2002). An Army at Dawn. Henry Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6288-2 – via Archive Foundation.

- Breuer, William B. (1985). Operation Torch: The Allied Gamble to Invade North Africa. New York: St.Martins Press.

- Brown, J. D. (1968). Carrier Operations in World War II: The Royal Navy. London: Ian Allan.

- Churchill, Winston (1951a). The Second World War, Vol 3: The Hinge of Fate.

- Churchill, Winston Spencer (1951b). The Second World War, Vol 5: Closing the Ring. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston.

- Danan, Professeur Yves Maxime (2019). République Française Capitale Alger, 1940–1944 Souvenirs. Paris: L'Harmattan.

- Eisenhower, Dwight D. (1948). Crusade in Europe. London: William Heinemann. OCLC 559866864 – via Archive Foundation.

- Edwards, Bernard (1999). Dönitz and the Wolf Packs. Brockhampton Press. ISBN 1-86019-927-5 – via Archive Foundation.

- Funk, Arthur L. (1974). The Politics of Torch. University Press of Kansas.

- Groom, Winston (3 April 2006). 1942: The Year That Tried Men's Souls. New York: Grove Press. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-8021-4250-4.

- Hague, Arnold (2000). The Allied Convoy System 1939–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-019-3.

- Howe, George F. (1993) [1957]. North West Africa: Seizing the Initiative in the West. The United States Army in World War II. Washington, D.C.: United States Army Center of Military History. LCCN 57060021. CMH Pub 6-1. Archived from the original on 28 May 2015. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

- Meyer, Leo J. (2000) [1960]. "Chapter 7: The Decision to Invade North Africa (Torch)". In Roberts Greenfield, Kent (ed.). Command Decisions. United States Army Center of Military History. CMH Pub 70-7. Archived from the original on 30 December 2007. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1947). Operations in North African Waters. History of United States Naval Operations in World War II. Vol. II. Boston: Little, Brown and Co. ISBN 0-7858-1303-9.

- Moses, Sam (November 2006). At All Costs; How a Crippled Ship and Two American Merchant Mariners Turned the Tide of World War II. Random House.

- O'Hara, Vincent P. (2015). Torch: North African and the Allied Path to Victory. Annapolis: Naval Institute.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; Molony, Brigadier C. J. C.; Flynn R.N., Captain F. C. & Gleave, Group Captain T. P. (2004) [1st HMSO 1966]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV. Uckfield, UK: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-068-8.

- Rohwer, J.; Hummelchen, G. (1992). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-105-X.

- Watson, Bruce Allen (2007) [1999]. Exit Rommel: The Tunisian Campaign, 1942–43. Stackpole Military History Series. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-3381-6. OCLC 40595324.

- Willmott, H.P. (1984). June, 1944. Poole, Dorset: Blandford Press. ISBN 0-7137-1446-8 – via Archive Foundation.

External links

- The Decision to Invade North Africa (TORCH) Archived 15 May 2010 at the Wayback Machine part of Command Decisions Archived 30 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine a publication of the United States Army Center of Military History

- Algeria-French Morocco Archived 5 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine a book in the U.S. Army Campaigns of World War II series of the United States Army Center of Military History

External links

- A detailed history of 8 November 1942

- Combined Ops

- History and photos of the operations of the USS Ranger and its Air Group during Operation Torch

- (North African Jewish Resistance to Nazis and the Holocaust)

- The accord Franco-Américan of Messelmoun (in French)

- Royal Engineers Museum Royal Engineers and Second World War (Operation Torch)

- Report of the Commander-in-Chief Allied Forces to the Combined Chief of Staff on Operations in North Africa

- Operation Torch: Allied Invasion of North Africa Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine article by Williamson Murray

- Eisenhower's report on operation Torch

- Operation TORCH Motion Pictures from the National Archives

- Operation Torch

- Operation Torch World War II

.svg.png.webp)