Fort Capuzzo

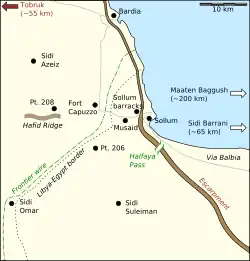

Fort Capuzzo (Italian: Ridotta Capuzzo) was a fort in the colony of Italian Libya, near the Libya–Egypt border, next to the Italian Frontier Wire. The Litoranea Balbo (Via Balbo) ran south from Bardia to Fort Capuzzo, 8 mi (13 km) inland, west of Sollum, then east across the Egyptian frontier to the port over the coastal escarpment. The fort was built during the Italian colonial repression of Senussi resistance in the Second Italo-Senussi War (1923–1931), as part of a barrier on the Libya–Egypt and Libya–Sudan borders.

| Fort Capuzzo/Ridotta Capuzzo | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War | |||||

Map showing Fort Capuzzo | |||||

| |||||

The Frontier Wire and a line of forts including Fort Capuzzo were used to stop the Senussi from moving freely across the border. The fort had four crenellated walls enclosing a yard. Living quarters had been built around the edges and provided the base for border guards and Italian army armoured car patrols. A track ran south from the fort, just west of the frontier wire and the border, to Sidi Omar, Fort Maddalena and Giarabub. The fort changed hands several times during the Western Desert campaign (1940–1943) of the Second World War.

Background

In 1922, Benito Mussolini continued the Riconquista of Libya in the Second Italo-Sanussi War (1921–1931).[1][2] The Frontier wire was built by the Italian army, under the command of General Rodolfo Graziani, in the winter of 1930–1931, as a means to repress Senussi resistance against the Italian colonisation. The frontier wire and fort system was used to hinder the movement of Senussi fighters and materials from Egypt.[3] The wire comprised four lines of 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) high stakes in concrete bases, laced with barbed wire, 320 km (200 mi) long, just inside the border from El Ramleh on the Gulf of Sollum, past Fort Capuzzo to Sidi Omar, then south, slightly to the west of the 25th meridian east, to the Libya–Egypt and Libya–Sudan borders.[4][2] Three large forts were built along the wire at Amseat (Fort Capuzzo), Scegga (Fort Maddalena) and Giarabub and six smaller ones at El Ramleh on the gulf of Sollum, at Sidi Omar, Sceferzen, Vescechet, Garn ul Grein and El Aamara.[3][lower-alpha 1] The wire was patrolled using armoured cars and aircraft from the forts, by the Italian army and border guards, who attacked anyone seen in the frontier zone.[5]

Second World War

1940

| First Action of Fort Capuzzo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of North African Campaign of the Second World War | |||||||

Rolls-Royce Armoured Car at the Frontier wire, 1940 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Francesco Argentino | |||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

7th Hussars 1st Royal Tank Regiment 4th Armoured Brigade No. 33 Squadron RAF No. 211 Squadron RAF |

2nd CC.NN. Division "28 Ottobre" Maletti Group | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 150 |

3,500 casualties 150 killed | ||||||

On 14 June 1940, four days after the Italian declaration of war on Britain, the 7th Hussars and elements of the 1st Royal Tank Regiment captured Fort Capuzzo. The Royal Air Force (RAF) contributed the Gladiator fighters of 33 Squadron and Blenheim bombers of 211 Squadron to the attack and the 11th Hussars took Fort Maddalena about 60 mi (97 km) further south.[6] The fort was not occupied long for lack of troops and equipment but demolition parties visited each night to destroy Italian ammunition and vehicles.[7] For the rest of June, the British patrolled to the north, south and west and began the Siege of Giarabub. The Italian 10th Army concentrated in the area from Bardia to Tobruk and brought forward the Maletti Group, a combined tank, infantry and artillery force, equipped with a company of Fiat M11/39 medium tanks, which were superior to their older L3/33 tankettes.[8]

The Italians reoccupied Fort Capuzzo and held it with part of the 2nd CC.NN. Division "28 Ottobre" (Lieutenant-General [Luogotenente Generale] Francesco Argentino). On 29 June, the Maletti Group repulsed British tanks with its artillery and then defeated a night attack.[8][9] During the frontier skirmishes from 11 June to 9 September, the British claimed to have inflicted 3,500 casualties for a loss of 150 men.[10] On 16 December, during Operation Compass (9 December 1940 – 9 February 1941) the 4th Armoured Brigade of the Western Desert Force captured Sidi Omar and the Italians withdrew from Sollum, Fort Capuzzo and the other frontier forts; Number 9 Field Supply Depot was established at the fort for the 7th Armoured Division.[11]

1941

On 10 April, after the Axis advance from El Agheila, small British mobile columns began to harass Afrika Korps units around Fort Capuzzo, which was captured by the Germans on 12 April. Attacks by Kampfgruppe Herf from 25 to 26 April, led the British columns to fall back.[12] During Operation Brevity (15–16 May) an operation to capture the area between Sollum and the fort and inflict casualties, the 22nd Guards Brigade Group and the 4th RTR was to capture the fort and then attack northwards. The operation began on 15 May and the fort was captured by the 1st Durham Light Infantry (1st DLI) and a squadron of Infantry tanks.[13]

A counter-attack by II Battalion, Panzer Regiment 5 (with eight operational tanks) inflicted many losses and forced the 1st DLI back to Musaid. The German force advanced from Fort Capuzzo on the following afternoon.[13] Three Italian battalions with artillery from the 102nd Motorised Division "Trento" took over the area between Sollum, Musaid and Fort Capuzzo. Late on 15 June, the 7th Royal Tank Regiment (7th RTR) attacked Fort Capuzzo during Operation Battleaxe (15–17 June) and scattered the defenders. The British tanks broke through but infantry were slow to follow up and the tanks were not able rapidly to exploit the success.[14]

Next day, the 22nd Guards Brigade consolidated at the fort and Panzer Regiment 8 attacked near Capuzzo, only to be repulsed by the 4th Armoured Brigade. German attempts to work round the British flank failed but reduced the tank regiments in the area to 21 runners. On 17 June, the danger of encirclement increased as German attacks reached Sidi Suleiman and the 22nd Guards Brigade was ordered to retreat at 11:00 a.m. The remnants of the armoured brigades covered the British withdrawal, eventually to the start line, assisted by the RAF.[14] On 22 November, the fort was captured by the 2nd New Zealand Division, during Operation Crusader (18 November – 30 December) which then advanced on Tobruk, apart from the 5th New Zealand Brigade which remained to capture the Sollum barracks.[15]

1942

Axis forces recaptured the fort around 22 June 1942, after the Battle of Gazala (26 May – 21 June 1942) capturing 500 long tons (510 t) of fuel and 930 long tons (940 t) of foodstuffs, despite demolitions since the British withdrawal from Gazala has begun on 14 June.[16] After the Second Battle of El Alamein (23 October – 11 November 1942) Fort Capuzzo changed hands for the last time. German rearguards retired from Sidi Barrani on 9 November; next day, the 22nd Armoured Brigade advanced on Fort Capuzzo from the south and by 11 November, the last Axis troops had withdrawn from the frontier, despite orders to hold the area from Halfaya to Sollum and Sidi Omar.[17]

Post war

After the Allied conquest in 1943, Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were ruled under the British Military Administration of Libya until Libyan independence in 1951, as a kingdom under Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi (King Idris of Libya). Fort Capuzzo and the frontier wire disappeared into obscurity.[18]

See also

Notes

- Soon after the frontier wire system was built, the colonial administration deported the people of the Jebel Akhdar to deny the rebels local support. More than 100,000 people were imprisoned in concentration camps at Suluq and El Agheila, where up to one third of the Cyrenaican population died in squalor. Omar Mukhtar was captured and killed in 1931, after which the resistance petered out, apart from the followers of Sheik Idris, Emir of Cyrenaica, who went into exile in Egypt.[2]

Footnotes

- Wright 1982, p. 42.

- Metz 1989.

- Christie 1999, p. 14.

- Cody 1956, p. 142.

- Wright 1982, p. 35.

- Playfair et al. 2004a, pp. 113, 118.

- Moorehead 2009, p. 13.

- Christie 1999, p. 49.

- Moorehead 2009, pp. 15–16.

- Playfair et al. 2004a, pp. 119, 187, 206.

- Playfair et al. 2004a, p. 278.

- Playfair et al. 2004b, pp. 36, 168, 204–205.

- Playfair et al. 2004b, pp. 159, 160–162.

- Playfair et al. 2004b, pp. 164, 168–170.

- Playfair et al. 2004c, p. 48.

- Playfair et al. 2004c, pp. 48, 281.

- Playfair et al. 2004d, pp. 93–95.

- B61 1966, p. 3.

Bibliography

- Christie, Howard R. (1999). Fallen Eagles: The Italian 10th Army in the Opening Campaign in the Western Desert, June 1940 – December 1940 (MA). Fort Leavenworth, KS: US Army Command and General Staff College. OCLC 465212715. A116763. Archived from the original on 16 February 2015. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Cody, J. F. (1956). "6 Sollum and Gazala". 28 Maori Battalion. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945. Wellington, NZ: War History Branch, Dept. of Internal Affairs. pp. 133–178. OCLC 4392594. Retrieved 8 March 2015.

- Libya–Egypt (United Arab Republic) Boundary (PDF). International Boundary Study. Washington, DC: United States Department of State Office of the Geographer. 15 January 1966. OCLC 42941644. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2015.

- Metz, H. C. (1989). Libya: A Country Study. Area Handbook Series (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Library of Congress, Federal Research Division. OCLC 473404917.

- Moorehead, A. (2009) [1944]. The Desert War: The Classic Trilogy on the North African Campaign 1940–43 (Aurum Press ed.). London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-1-84513-391-7.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004a) [1954]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. I (pbk. facs. repr.Naval & Military Press ed.). HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-065-8.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004b) [1956]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Germans come to the help of their Ally (1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. II (pbk. facs. repr. Naval & Military Press ed.). HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-066-5.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004c) [HMSO 1960]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: British Fortunes reach their Lowest Ebb (September 1941 to September 1942). History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. III. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 978-1-84574-067-2.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; et al. (2004d) [1966]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. Vol. IV (repr. facs. pbk. Naval & Military Press ed.). Uckfield: HMSO. ISBN 978-1-84574-068-9.

- Wright, J. L. (1982). Libya, A Modern History. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-2767-9.

Further reading

- Arielli, Nir (2015). "Colonial Soldiers in Italian Counter-Insurgency Operations in Libya, 1922–32". British Journal for Military History. I (2). ISSN 2057-0422. Archived from the original on 2018-12-02. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- Latimer, Jon (2001). Tobruk 1941: Rommel's Opening Move. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-0-275-98287-4.

- Paterson, Ian A. "History of the British 7th Armoured Division: Operation Brevity". Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 28 February 2015.

- Rodd, F. (1970) [1948]. British Military Administration of Occupied Territories in Africa during the Years 1941–1947 (2nd Greenwood Press, CT ed.). London: HMSO. OCLC 1056143039.