Louis IV of France

Louis IV (September 920/921[1] – 10 September 954[2]), called d'Outremer or Transmarinus (both meaning "from overseas"), reigned as King of West Francia from 936 to 954. A member of the Carolingian dynasty, he was the only son of king Charles the Simple and his second wife Eadgifu of Wessex, daughter of King Edward the Elder of Wessex.[3] His reign is mostly known thanks to the Annals of Flodoard and the later Historiae of Richerus.

| Louis IV | |

|---|---|

| |

| King of West Francia | |

| Reign | 936–954 |

| Coronation | 936 in Laon |

| Predecessor | Rudolph |

| Successor | Lothair |

| Born | September 920 / September 921 Laon |

| Died | 10 September 954 (aged 33-34) Reims |

| Burial | Saint-Remi Abbey, Reims, France |

| Spouses | Gerberga of Saxony |

| Issue Detail | Lothair, King of West Francia Charles, Duke of Lower Lorraine Matilda, Queen of Burgundy |

| House | Carolingian |

| Father | Charles the Simple |

| Mother | Eadgifu of Wessex |

Childhood

Louis was born to King Charles III and his 2nd wife Eadgifu, in the heartlands of West Francia's Carolingian lands between Laon and Reims in 920 or 921.[4] He was descended both from Charlemagne and King Alfred the Great. From his father's first marriage with Frederuna (d. 917) he had six older half-sisters.

After the dethronement and capture of Charles the Simple in 923, following his defeat at the Battle of Soissons, queen Eadgifu and her infant son took refuge in Wessex (for this he received the nickname of d'Outremer) at the court of her father King Edward, and after Edward's death, of her brother King Æthelstan. Young Louis was raised in the Anglo-Saxon court until his teens. During this time he enjoyed legendary stories about Edmund the Martyr (king of East Anglia), an ancestor of his maternal family who had heroically fought against the Vikings.[5]

Louis became the heir to the western branch of the Carolingian dynasty after the death of his captive father in 929, and in 936, at the age of 15, was recalled from Wessex by the powerful Hugh the Great, margrave of Neustria, to succeed the Robertian King Rudolph who had died.[6]

Once he took the throne, Louis wanted to free himself from the tutelage of Hugh the Great, who, with his title of duke of the Franks was the second most powerful man after the King. In 939, the young monarch attempted to conquer Lotharingia; however, the expedition was a failure and his brother-in-law, King Otto I of East Francia counterattacked and besieged the city of Reims in 940. In 945, following the death of William I Longsword, duke of Normandy, Louis tried to conquer his lands, but was captured by the Normans and handed over to Hugh the Great.[7]

The Synod of Ingelheim in 948 allowed the excommunication of Hugh the Great[8] and released Louis from his long tutelage. From 950 Louis gradually imposed his rule in the northeast of the kingdom, building many alliances (especially with the counts of Vermandois) and under the protection of the Ottonian kingdom of East Francia.

Assumption of crown

In spring of 936 Hugh the Great sent an embassy to Wessex inviting Louis to "come and take the head of the kingdom" (Flodoard). King Æthelstan, his uncle, after forcing the embassy to swear that the future king will have the homage of all his vassals, permitted him the return home with his mother Eadgifu, some bishops and faithful servants.[9] After a few hours of sea journey, Louis received the homage of Hugh and some Frankish nobles on the beach of Boulogne, who kissed his hands. Chronicler Richerus gives us an anecdote about this first encounter:

- Then the Duke hastily brought a horse decorated with the royal insignia. By the time he wanted to put the King in the saddle, the horse ran in all directions; but Louis, an agile young man, jumped suddenly, without stirrups, and tamed the animal. This pleased all those presented and caused recognition from all.[10]

Louis and his court then began the trip to Laon where the coronation ceremony was to take place. Louis IV was crowned king by Archbishop Artald of Reims on Sunday, 19 June 936,[11] probably at the Abbey of Notre-Dame and Saint-Jean in Laon,[12][13] perhaps at the request of the King since it was a symbolic Carolingian town and he was probably born there.

The chronicler Flodoard records the events as follows:

| Brittones a transmarinis regionibus, Alstani regis praesidio, revertentes terram suam repetunt. Hugo comes trans mare mittit pro accersiendo ad apicem regni suscipiendum Ludowico, Karoli filio, quem rex Alstanus avunculus ipsius, accepto prius jurejurando a Francorum legatis, in Franciam cum quibusdam episcopis et aliis fidelibus suis dirigit, cui Hugo et cetero Francorum proceres obviam profecti, mox navim egresso, in ipsis littoreis harenis apud Bononiam, sese committunt, ut erant utrinque depactum. Indeque ab ipsis Laudunum deductus ac regali benedictione didatus ungitur atque coronatur a domno Artoldo archiepiscopo, praesentibus regni principibus cum episcopis xx et amplius.[14] | "The Bretons, returning from the lands across the sea with the support of King Athelstan, came back to their country. Duke Hugh sent across the sea to summon Louis, son of Charles, to be received as king, and King Athelstan, his uncle, first taking oaths from the legates of the Franks, sent him to the Frankish kingdom with some of his bishops, and other followers. Hugh and the other nobles of the Franks went to meet him and committed themselves to him[;] immediately he disembarked on the sands of Boulogne, as had been agreed on both sides. From there he was conducted by them to Laon, and, endowed with the royal benediction, he was anointed and crowned by the lord Archbishop Artold, in the presence of the chief men of his kingdom, with 20 bishops."[15] |

During the ritual, Hugh the Great acted as squire bearing the King's arms. Almost nothing is known about the coronation ceremony of Louis IV. It seems certain that the King would wear the crown and sceptre of his predecessor. He must have promised before the bishops of France to respect the privileges of the Church. Maybe he received the ring (a religious symbol), the sword and the stick of Saint Remigius (referring to the baptism of Clovis I). Finally, the new King (perhaps like his ancestor Charles the Bald) used a blue silk coat called Orbis Terrarum with cosmic allusions (referring to the Vulgate) and the purple robe with precious stones and gold incrustations also used by Odo in 888) and his own son Lothair during his coronation in 954.[16][17]

Historians have wondered why the powerful Hugh the Great called the young Carolingian prince to throne instead of taking it himself, as his father had done fifteen years earlier. First, he had many rivals, especially Hugh, Duke of Burgundy (King Rudolph's brother) and Herbert II, Count of Vermandois who probably would have challenged his election. But above all, it seems that he was shocked by the early death of his father. Richerus explains that Hugh the Great remembered his father who had died for his "pretentions" and this was the cause of his short and turbulent reign. It was then that "the Gauls, anxious to appear free to elect their King, assembled under the leadership of Hugh to deliberate about the choice of a new King".[10] According to Richerus, Hugh the Great delivered the following speech:

- King Charles died miserably. If my father and us, we hurt your Majesty by some of our actions, we must use all our efforts to erase the trace. Although following your unanimous desire my father committed a great crime reigning, since only one had the right to rule and was alive, he deserved to be imprisoned. This, believe me, wasn't the will of God. Also I never had to take the place of my father.[10]

Hugh the Great knew that the Robertian dynasty had not achieved much; his uncle Odo had died after a few years of reign, abandoned by the nobles. Hugh's father, Robert I, was killed during the battle of Soissons after only months of reign and his brother-in-law Rudolph couldn't stop the troubles that multiplied in the Kingdom during his reign. Finally, Hugh didn't have a legitimate male heir: his first wife Judith (daughter of Count Roger of Maine and Princess Rothilde) died in 925 after eleven years of childless union; in 926 he married Princess Eadhild of Wessex, sister of Queen Eadgifu, who also didn't bear him any children.[18] In addition, the marriage with Eadhild, actively promoted by Eadgifu, was made in order to sever an eventual dangerous link between families of Hugh and Count Heribert II of Vermandois.[19]

Regency of Hugh the Great

Having arrived on the continent, Louis IV was a young man of fifteen, who spoke neither Latin nor Old French, but probably spoke Old English. He knew nothing about his new kingdom. Hugh the Great, after negotiating with the most powerful nobles of the Kingdom – (William I Longsword of Normandy, Herbert II of Vermandois and Arnulf of Flanders) – was appointed guardian of the new king.[20]

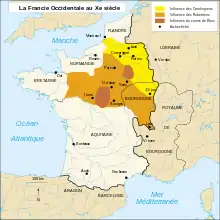

The young king quickly became a puppet of Hugh the Great, who had reigned de facto since the death of his father Robert in 923. Territorially, Louis IV was quite helpless since he possessed few lands around the ancient Carolingian domains (Compiègne, Quierzy, Verberie, Ver-lès-Chartres and Ponthion), and some abbeys (Saint-Jean in Laon, Saint-Corneille in Compiègne, Corbie and Fleury-sur-Loire) and collected the revenues from the province of Reims. We know that king had the power to appoint the suffragants of the Archbishopric of Reims. During this time Laon became the centre of the small Carolingian heartland, compared with the possessions in the Loire Valley of the Robertians.[20]

Hugh the Great's power came from the extraordinary title of dux Francorum (duke of the Franks)[21] that Louis IV repeatedly confirmed in 936, 943 and 954; and his rule over the Marches of Neustria, where he reigned as princeps (territorial prince). This title was for the first time formalized by the Royal Chancery.[22][23]

Thus the royal edicts of the second half of 936 confirm the pervasiveness of Hugh the Great: it is said that Duke of the Franks "in all but reigned over us".[24]

Hugh also denied the rights to the principality of Burgundy that Hugh the Black thought he had acquired after the death of his brother King Rudolph.[25]

From the beginning of 937 Louis IV, called by some "The King of the Duke" (le roi du duc)[26] tried to halt the virtual regency of the Duke of the Franks; in the contemporary charters, Hugh the Great appears only as "count" as if the ducal title was taken from him by the king. But Louis IV hesitated about this move, because the ducal title was already given to Hugh the Great by Charles the Simple in 914. But a serious misconduct probably took place at that time, because Louis IV removed the title from him.[27] For his part, Hugh the Great continued to claim to be the duke of the Franks. In a letter from 938 the pope called him duke of the Franks, three years later (941) he presided a meeting in Paris during which he raised personally, in the manner of a king, his viscounts to the rank of counts. Finally, Hugh the Great had the decisive respect of the entire episcopate of France.[28]

Difficulties during the early years, 938–945

Louis IV and his supporters, 938–939

The rivalries between the nobility appeared as the only hope for the Louis IV to free himself from the regency of Hugh the Great. In 937 Louis IV began to rely more on his Chancellor Artald, Archbishop of Reims, Hugh the Black and William I Longsword, all enemies of Hugh the Great. He also received the homage of other important nobles like Alan II, Duke of Brittany (who also spent part of his life in England) and Sunyer, Count of Barcelona.[29] Nevertheless, the support for the young king was still limited, until the Pope clearly favored him after he forced the French nobles to renew their homage to the king in 942.[28] The King's power in the south was symbolic since the death of the last Count of the Spanish March in 878.[30]

Hugh the Great's response to the King's alliances approximating Herbert II of Vermandois, a very present ruler in minor France:[31] it possessed a tower, called château Gaillot in the city of Laon.[32] The following year, the King seized the tower but Herbert II conquered the fortresses of Reims. Flodoard related the events as follows:

- But Louis, called by the archbishop Artaud returned and besieged Laon where a new citadel was built by Herbert. He undermines and overthrows many machines walls and finally took it with great difficulty.[33]

War over Lotharingia

Louis IV then looked to the Lotharingia, the land of his ancestors and began attempts to conquer it. In 939 Gilbert, Duke of Lotharingia rebelled against King Otto I of East Francia and offered the crown to Louis IV, who received homage of the Lotharingian aristocracy in Verdun on his way to Aachen. On 2 October 939, Gilbert drowned in Rhine while escaping from the forces of Otto I after the defeat at the Battle of Andernach. Louis IV used this opportunity to strengthen his domain over Lotharingia by marrying Giselbert's widow, Gerberga of Saxony (end 939), without the consent of her brother King Otto I. The wedding did not stop Otto I who, after alliance with Hugh the Great, Herbert II of Vermandois and William I Longsword, resumed his invasion of Lotharingia and advanced towards Reims.[34]

Crisis of the royal power, 940–941

In 940 the East Frankish invaders finally conquered the city of Reims, where archbishop Artald was expelled and replaced by Hugh of Vermandois, younger son of Herbert II, who also seized the patrimony of Saint-Remi. About this, Flodoard wrote:

- These are the same Franks who want this King, who crossed the sea at their request, the same ones who sworn loyalty to him and lied to God and that King?[33]

Flodoard also publishes at the end of his Annals the testimony of a girl from Reims (the Visions of Flothilde) who predicted the expulsion of Artald from Reims. Flothilde mentioned that the saints are alarmed about the disloyalty of the nobles against the King. This testimony was widely believed, especially among the population of Reims, who believed that the internal order and peace come from the oaths of loyalty to the King, while Artald was blamed of having forsaken divine service.[35] Contemporary Christian tradition affirmed that Saint Martin attended the coronation of 936. Now the two royal patron saints, Saint Remi and Saint Denis, seem to have turned back to the King's rule. To soften the anger of the saints, in the middle of the siege of Reims by Hugh the Great and William I Longsword, Louis IV went to Saint Remi Basilica and promised to the saint to pay him a pound of silver every year.[36]

In the meanwhile, Hugh the Great and his vassals had sworn allegiance to Otto I, who moved to the Carolingian Palace of Attigny before his unsuccessful siege of Laon. In 941 the royal army, which tried to oppose Otto's invasion, was defeated and Artald was forced to submit to the rebels. Now Louis IV was surrendered in the only property that remained in his hands: the city of Laon. Otto I believed that the power Louis IV was sufficiently diminished and proposed a reconciliation with the Duke of the Franks and the Count of Vermandois. From that point on, Otto I was the new arbitrator in the West Francia.[34]

Intervention in Normandy, 943–946

On 17 December 942 William I Longsword was ambushed and killed by men of Arnulf I, Count of Flanders at Picquigny and on 23 February 943 Herbert II, Count of Vermandois died of natural causes.[37] The heir of Duchy of Normandy was Richard I, the ten-year-old son of William born from his Breton concubine, while Herbert II left as heirs four adult sons.

Louis IV took advantage of the internal disorder in the Duchy of Normandy and entered Rouen, where he received the homage from part of the Norman aristocracy and offered his protection to the young Richard I with the help of Hugh the Great.[38] The regency of Normandy was entrusted to the faithful Herluin, Count of Montreuil (who was also a vassal of Hugh the Great), while Richard I was imprisoned first in Laon and then in Château de Coucy. In Vermandois, the King also took measures to diminish the power of Herbert II's sons by dividing their lands between them: Eudes (as Count of Amiens), Herbert III (as Count of Château-Thierry), Robert (as Count of Meaux) and Albert (as Count of Saint-Quentin). Albert of Vermandois took the side of the King and paid homage to him, while the Abbey of Saint-Crépin in Soissons was finally given to Renaud of Roucy.[39] In 943, during the homage given to the King, Hugh the Great recovered the ducatus Franciae (Duchy of France) title and the rule over Burgundy.[40]

During the summer of 945 Louis IV went to Normandy after being called by his faithful Herluin, who was a victim of a serious revolt. While the two were riding, they were ambushed near Bayeux.[41] Herluin was killed, but Louis IV managed to escape to Rouen; where he was finally captured by the Normans. The kidnappers demanded from Queen Gerberga that she send her two sons Lothair and Charles as hostages in exchange for the release of her husband. The Queen only sent her youngest son Charles, with Bishop Guy of Soissons taking the place of Lothair, the eldest son and heir.[42] Like his father, Louis IV was kept in captivity, then sent to Hugh the Great. On his orders, the king was placed under the custody of Theobald I, Count of Blois for several months.[43] The ambush and capture of the King were probably ordered by Hugh the Great, who wanted to permanently end his attempts of political independence.[44] Ultimately, probably by the pressure of the Frankish nobles and Kings Otto I and Edmund I of England, Hugh the Great decided to release Louis IV.[43]

Hugh was the only one who would decide if Louis IV could be restored or deposed. In return for the release of the King, he demanded the surrender of Laon,[45] which was entrusted to his vassal Thibaud.[43] The Carolingian kinship was in the abyss, because it no longer held or controlled anything.

In June 946, a royal charter called optimistically the "eleventh year of the reign of Louis when he had recovered the Francia". This charter is the first official text who identified only the Western Frankish kingdom (sometimes called West Francia by some historians).[46] This statement is consistent with the fact that the title of King of the Franks, used since 911 by Charles the Simple[46] was thereafter continuously claimed by the Kings of the Western Kingdom after the Treaty of Verdun, including the non-Carolingians ones. Among the Kings of the East, sometimes called Germanic Kings, this claim was occasional and disappeared completely after the 11th century.[47]

Ottonian hegemony, 946–954

Trial of Hugh the Great, 948–949

Otto I was not satisfied with the growing power of Hugh the Great who, although not accepted by the whole kingdom, respected the division of powers. In 946 Otto I and Conrad I of Burgundy raised an army and tried to take Laon and then Senlis.[48] They invaded Reims with a large army, according to Flodoard. Archbishop Hugh of Vermandois escaped and Artald was restored. "Robert, Archbishop of Trier and Frederick, Archbishop of Mainz take everyone by the hand" (Flodoard). A few months later, Louis IV joined the fight against Hugh the Great and his allies at the Battle of Rouen. In the spring of 947, Louis and his wife Gerberga spent the Easter holidays in Aachen at the court of Otto I, asking him for help in their war against Hugh the Great.[49]

Between late 947 and late 948, four imperial synods were held by Otto I between Meuse and Rhine to settle the fate of the Archbishopric of Reims and Hugh the Great.[50] In Synod of Ingelheim (June 948) participated the apostolic legate, thirty German and Burgundian bishops and finally Artald and his suffragants of Laon among the Frankish clerics. Louis IV presented his claims against Hugh the Great at the synod. The surviving final acts determined: "Anybody had the right to undermine the royal power or treacherously revolted against their King. We therefore decide that Hugh was the invasor and abductor of Louis, and he will be struck with the sword of the excommunication unless he presents himself and give a satisfaction to us for his perversity".[51]

But the Duke of the Franks, not paying attention to the sentence, devastated Soissons, Reims and profaned dozens of churches. In the meanwhile, his vassal and relative Theobald I, Count of Blois (nicknamed "the Trickster") who had married Luitgarde of Vermandois, daughter of Herbert II of Vermandois and widow of William I Longsword, had built a fortress in Montaigu in Laon to humiliate the king, and seized the lordship of Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique in Reims. The Synod of Trier (September 948) decided to excommunicate him for his actions. Guy I, Count of Soissons, who ordained Hugh of Vermandois, must repent, while Thibaud of Amiens and Yves of Senlis, who both consecrated Hugh, were excommunicated. The King, with the help of Arnold, deposed Thibaud from the seat of Amiens and placed the faithful Raimbaud in his place (949).[52]

Return of the balance

The last step in the emancipation of Louis IV shows that his reign wasn't entirely negative. In 949 he entered Laon, where by command of Hugh the Great, Theobald I of Blois surrendered to him the fortress he had built a few months earlier.[53] The King recovered, at the expense of Herbert II's vassals, the château of Corbeny which his father had given to Saint-Remi of Reims and also authorized archbishop Artald to mint coins in his city.[54]

In 950 Louis IV and Hugh the Great finally reconciled. After the death of Hugh the Black in 952, Hugh the Great captured his half of Burgundy. Louis IV, now allied with Arnulf I of Flanders and Adalbert I, Count of Vermandois, exercised real authority only north of the river Loire. He also rewarded Liétald II of Mâcon and Charles Constantine of Vienne for their loyalty. For a long time Louis IV and his son Lothair were the last kings to venture south of the river Loire.

In 951 Louis IV fell seriously ill during a stay in Auvergne and decided to associate to the throne his eldest son and heir, the ten-year-old Lothair.[55] During his stay, he received homage of Bishop Étienne II, brother of the viscount of Clermont. Louis IV recovered from his disease thanks to the care of his wife Gerberga, who during the reign of her husband had a key role. The royal couple had seven children, of whom only three survived infancy: Lothair, the eldest son and future King – that Flodoard cites not to be confused with the son of Louis the Pious: Lotharius puer, filius Ludowici (infant Lothair, son of Louis)–, Mathilde – who in 964 married King Conrad I of Burgundy – and Charles – who was invested as Duke of Lower Lorraine by his cousin Emperor Otto II in 977–.[56]

During the 950s, the royal power network was entrenched by construction of several palaces in the towns that were recovered by the King. Under Louis IV (and also during the reign of his son), there is a geographical tightening of royal lands around Compiègne, Laon and Reims which eventually gave Laon an incontestable primacy. Thus, through the charters issued by the Royal Chancery, can be followed the stays of Louis IV. The King spent mostly of his time in the palaces of Reims (21% of the charters), Laon (15%), Compiègne and Soissons (2% for each of them).[57]

Flodoard records in 951 that Queen Eadgifu (Ottogeba regina mater Ludowici regis), who since her return with her son to France retired to the Abbey of Notre Dame in Laon (abbatiam sanctæ Mariæ...Lauduni), where she became the Abbess, was abducted from there by Herbert III of Vermandois, Count of Château-Thierry (Heriberti...Adalberti fratris), who married her shortly after; the King, furious about this (rex Ludowicus iratus) confiscated the Abbey of Notre Dame from his mother and donated it to his wife Gerberga (Gerbergæ uxori suæ).[58][59]

Death of Louis IV and the Legend of the Wolf

In the early 950s, Queen Gerberga developed an increased eschatological fear, and began to consult Adso of Montier-en-Der; being highly educated, she commissioned to him the De ortu et tempore antichristi (The birth and era of the Antichrist). Adso reassured the Queen that the arrival of the Antichrist would not take place before the end of the Kingdoms of France and Germany, the two Imperia fundamentals of the universe. In consequence, the Frankish King could continue his reign without fear, because Heaven was the door of legitimacy.[60]

At the end of the summer of 954, Louis IV went riding with his companions on the road from Laon to Reims. As he crossed the forest of Voas (near to his palace in Corbeny), he saw a wolf and attempted to capture it. Flodoard, from whom these details are known, said that the King fell from his horse. Urgently carried to Reims, he eventually died from his injuries on 10 September. For the Reims canons, the wolf whom the king tried to hunt wasn't an animal but a fantastic creature, a divine supernatural intervention.

Flodoard recalled indeed that in 938 Louis IV had captured Corbeny in extreme brutality and without respecting the donations to the monks made by his father. Thus God could punish the King and his descendants with the curse of the wolf as a "plague". The later events are disturbing. According to Flodoard Louis reportedly died from tuberculosis (then called pesta elephantis); in 986 his son Lothair died by a "plague"[61] after he besieged Verdun, and finally his grandson Louis V died in 987 from injuries received when falling from his horse while hunting, a few months after he besieged Reims for the trial of archbishop Adalberon.[62]

Dynastic memorial and burial

Gerberga, a dynamic and devoted wife, supported the burial of her late husband at the Abbey of Saint-Remi.[63] Unusually for the Carolingians, she took care of the dynastic memorial (mémoire dynastique) of Louis IV. The Queen, from Ottonian descent, was constantly at the side of her husband, supporting him and being active in the defence of Laon (941) and of Reims (946), accompanied him on the military expeditions to Aquitaine (944) and Burgundy (949), and was also active during his period of imprisonment in 945-946.[64] By France and Germany, the role of queens was different: the memorial mostly was a task of males. Written shortly after 956, perhaps by Adso of Montier-en-Der (according to Karl Ferdinand Werner) the Life of Clotilde[65] proposes to Queen Gerberga to build a church destined to be burial place of members of the Carolingian dynasty: the Abbey of Saint-Remi; moreover in a charter dated 955, King Lothair, following the desires of his mother, confirmed the immunity of Saint-Remi as the place of coronations and royal necropolis.

The tomb of Louis IV was later destroyed during the French Revolution. At that time, the two tombs of Louis IV and his son Lothair were in the centre of the Abbey, the side of the Epistle reserved to Louis IV and the side of the gospel to Lothair. Both remains were moved in the middle of the 18th century and transported to the right and left of the mausoleum of Carloman I first under the first arch of the collateral nave towards the sacristy of Saint-Remi Abbey. The statues placed on the original graves were left there. Both statues were painted and the golden Fleur-de-lis on each of the Kings' capes was easily visible. A graphic description of the tombs was made by Bernard de Montfaucon.[66][67] Louis IV was shown seated on a throne with a double-dossier. He was depicted as full-bearded, wearing a bonnet and dressed with a chlamys and also was holding a sceptre who ended with a pine cone. The throne of Louis IV was similar to a bench placed on a pedestal of the same material. The seat had a back that was above the royal head he was home with a gable roof, three arches decorated the underside of the roof. The base on which rested his feet was decorated at the corners with figures of children or lions.[68]

Children

Louis IV and Gerberga had seven children:[69]

- Lothair (end 941 – 2 March 986), successor of his father.

- Mathilde (end 943 – 27 January 992), married in 964 to King Conrad I of Burgundy.[70]

- Charles (January 945 – Rouen, before 953). Guillaume de Jumièges records that a son of Louis IV hostage of the Normans after 13 July 945 to secure the release of his father,[71] although it's unknown whether this son was Charles, who would have been a baby at the time, normally too young to have been used as a hostage according to then current practice.

- Daughter (947 / early 948 – died young). Flodoard records that Chonradus...dux baptised filiam Ludowici regis in the middle of his passage dealing with 948.[72] She must have been born in the previous year, or very early in the same year, if the timing of the birth of King Louis's son Louis is correctly dated to the end of 948.

- Louis (December 948 – before 10 September 954). The Genealogica Arnulfi Comitis names (in order) Hlotharium Karolum Ludovicum et Mathildim as children of Hludovicum ex regina Gerberga. Flodoard records the birth of regi Ludowico filius...patris ei nomen imponens at the end of his passage concerning 948.[73]

- Charles (summer 953 – 12 June 991), invested as Duke of Lower Lorraine by Emperor Otto II in May 977 at Diedenhofen.

- Henry (summer 953 – died shortly after his baptism). Flodoard records the birth of twins to Gerberga regina in 953 unus Karolus, later Heinricus, sed Henricus mox post baptismum defunctus est.[74]

Succession

Immediately after Louis IV died, his widow Gerberga was forced to obtain the approval of Hugh the Great for the coronation of her son Lothair, which took place on 12 November 954 at the Abbey of Saint-Remi in Reims.[75]

The regency of the Kingdom was held firstly by Hugh the Great, and after his death in 956 by Gerberga's brother Bruno the Great, Archbishop of Cologne and Duke of Lotharingia until 965, marking the Ottonian influence over France during all the second half of the 10th century.[64] Thus, the end of Louis IV's reign and the beginning of the rule of Lothair, wasn't the "dark century of iron and lead [...] but rather [...] the last century of the Carolingian Europe".[76]

Louis IV's youngest surviving son Charles, known as Charles of Lower Lorraine, settled on an island in the Zenne river in the primitive pagus of Brabant, where he erected a castrum in the town called Bruoc Sella or Broek Zele, which later became Brussels.

Notes

- The precise date of birth of Louis IV is unknown. The Annals of Flodoard indicate that he was fifteen in 936 and that he was born in the region of Laon-Reims.

- Anselm de Gibours (1726). Histoire généalogique et chronologique de la maison royale de France [Genealogical and chronological history of the royal house of France] (in French). Vol. 1 (3rd ed.). Paris: La compagnie des libraires. p. 36.

- Donald A. Bullough, Carolingian Renewal: Sources and Heritage, (Manchester University Press, 1991), 286

- Hartley, C. (2003). A Historical Dictionary of British Women. Routledge history online. Taylor & Francis Books Limited. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-85743-228-2. Retrieved 2 August 2018.

The daughter of King Edward the Elder, Eadgifu became the second wife of the beleaguered Carolingian King of West Frankia, Charles the Simple. In September 920 or 921 she gave birth to Louis, the future Louis IV, called 'd'Outremer' on ...

- Poly 1990, p. 296.

- "Louis IV, King of the Franks", The British Museum

- Crouch, David. The Normans (Hambledon Continuum, London & New York, 2007), p. 16

- Bradbury, Jim.The Capetians: Kings of France, 987-1328 (Hambledon Continuum, London & New York, 2007), p. 40

- Sot 1988, p. 724.

- Sot 1988, p. 727

- Pierre Riche, The Carolingians, Transl. Michael Idomir Allen, (University of Pennsylvania Press, 1993), 256.

- Michel Bur: La Champagne médiévale, 2005, p. 657.

- The chroniclers Aimon de Fleury recorded in his Gestis francorum that Louis IV was crowned in the Abbey of Saint-Vincent in Laon.

- Flodoard, Annales 936, ed. P. Lauer.

- Dorothy Whitelock (tr.), English Historical Documents c. 500–1042. 2nd ed. London, 1979. p. 344.

- Isaïa 2009, p. 131.

- Pinoteau 1992, pp. 76-80.

- Depreux 2002, pp. 136-137.

- Sarah Foot: Dynastic Strategies: The West Saxon Royal Family in Europe. In: David Rollason, Conrad Leyser, Hannah Williams: England and the Continent in the Tenth Century: Studies in Honour of Wilhelm Levison (1876–1947). Brepols, 2010, p. 246.

- Theis 1990, p. 169.

- Title held by Charles Martel and Pepin the Short when they were mayors of the Palace for the last Merovingian kings.

- Guillot, Sassier 2003, p. 170.

- Theis 1990, p. 170.

- It's understood that the duke of the Franks is now the first person in the kingdom after the king. Charter of Louis IV, n° 4, 26 December 936. Guillot, Sassier 2003, p. 170.

- In fact, in the kingdom of the Franks during the 9th century, there can be only one duke. If Hugh the Great proclaimed himself duke of all the Franks and over all the kingdoms (Burgundy and Aquitaine included) this means that he doesn't recognize the legitimacy of Hugh the Black as duke of Burgundy. This quarrel ended in 936-937 when the two enemies agreed to share Burgundy.

- Quote of Laurent Theis. C. Bonnet, Les Carolingiens (741-987), Paris, Colin, 2001, p. 214.

- Guillot, Sassier 2003, pp. 170-171

- Guillot, Sassier 2003, p. 171.

- In fact, until the 10th century, the Catalan nobles go to the royal palace in Laon to confirm privileges for their churches and ensure their loyalty to the King. And Wilfred, brother of the Count of Barcelona, received a charter from Louis IV renewing his rights in the Abbey of Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa (937).

- Theis 1990, pp. 155-157.

- The minor France is the region between Loire and Meuse.

- Theis 1990, p. 171.

- Theis 1990, p. 172.

- Theis 1990, pp. 171-172.

- Isaïa 2009, p. 49.

- Isaïa 2009, p. 317.

- According to contemporary sources (Dudon of Saint-Quentin and Flodoard of Reims), the murder was an act of revenge of the Count of Flanders who had just lost in favor of William I the city of Montreuil because the count of the Normans had approached King Louis IV to the detriment of Arnold and his lord Otto I of Germany. Dudon of Saint-Quentin: De Moribus et actis primorum Normanniae ducum, ed. Jules Lair, Caen, 1865, p. 84.

- Riché 1999, p. 287.

- Theis 1990, p. 173.

- Guillot, Sassier 2003, p. 172.

- The Normans had never accepted the regency of Herluin. Dudo of Saint-Quentin, op. cit., p. 90.

- It seems that Richard I was returned to the Normans at the same time. Dudon of Saint-Quentin, op. cit., p. 92.

- Sassier 1987, p. 116.

- Theis 1990, p. 174

- Richer de Reims: Gallica Histoire de son temps Book II, p. 203 Archived 27 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine.

- Hervé Pinoteau: La symbolique royale française, ve ‑ xviiie siècles, PSR, p. 115.

- Hervé Pinoteau: La symbolique royale française, ve ‑ xviiie siècles, PSR, p. 159.

- Sassier 1987, p. 117.

- Régine Le Jan: Femmes, pouvoir et société dans le haut Moyen Âge, 2001, p. 35.

- Theis 1990, pp. 174-175.

- Theis 1990, p. 176.

- Theis 1990, p. 177, 200.

- Sassier 1987, p. 118.

- Flodoard: Histoire de l'Église de Reims, pp. 548-549.

- Isaïa 2009, pp. 190-191.

- Flodoard: Histoire de l'Église de Reims, p. 550.

- Renoux 1992, p. 181, 191.

- Flodoard: Annals, Monumenta Germaniæ Historica Scriptorum III, p. 401.

- Jean nDunba: West Francia: The Kingdom. In: Timothy Reuter. The New Cambridge Medieval History III. Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 384.

- Sassier 2002, pp. 188-189.

- Richer de Reims: Histoire de son temps – La mort de Lothaire, Book III, p. 137.

- Poly 1990, pp. 292-294.

- Jim Bradbury, The Capetians: Kings of France 987-1328, (Hambledon Continuum, 2007), 41.

- Isaïa 2009, p. 271

- Michel Rouche: Clovis, histoire et mémoire online, 1997, p. 147.

- Bernard de Montfaucon: Les monuments de la monarchie française, vol. I, p. 346.

- Prosper Tarbé: Les sépultures de l'église Saint-Remi de Reims, 1842.

- Christian Settipani: La Préhistoire des Capétiens, ed. Patrick Van Kerrebrouck, 1993, p. 327.

- Christian Settipani: La Préhistoire des Capétiens, éd. Patrick Van Kerrebrouck, 1993, p. 330.

- Burgundy and Provence, 879-1032, Constance Brittain Bourchard, The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 3, C.900-c.1024, ed. Rosamond McKitterick and Timothy Reuter, (Cambridge University Press, 1999), 342.

- Willelmi Gemmetencis Historiæ (Du Chesne, 1619), Book IV, chap. VIII, p. 243.

- Flodoard: Annals, Monumenta Germaniæ Historica Scriptorum III, p. 397.

- Flodoard: Annals, Monumenta Germaniæ Historica Scriptorum III, p. 398.

- Flodoard: Annals, Monumenta Germaniæ Historica Scriptorum III, p. 402.

- Guillot, Sassier 2003, p. 173.

- Riché 1999, p. 279.

References

Books

- Flodoard: Annales, ed. Philippe Lauer, Les Annales de Flodoard. Collection des textes pour servir à l'étude et à l'enseignement de l'histoire 39. Paris, Picard, 1905.

- Geneviève Bührer-Thierry: Pouvoirs, Église et société. France, Bourgogne et Germanie (888-XIIe siècle), Paris, CNED, 2008.

- Philippe Depreux: Charlemagne et les Carolingiens, Paris, Tallandier, 2002.

- Jean-Philippe Genet: Les îles Britanniques au Moyen Âge, Paris, Hachette, 2005

- Marie-Céline Isaïa: Pouvoirs, Église et société. France, Bourgogne et Germanie (888-1120), Paris, Atlande, 2009.

- Robert Delort: La France de l'an Mil, Paris, Seuil, 1990.

- Olivier Guillot, Yves Sassier: Pouvoirs et institutions dans la France médiévale, vol. 1: Des origines à l'époque féodale, Paris, Colin, 2003.

- Dominique Iogna-Prat: Religion et culture autour de l'an Mil, Paris, Picard, 1990.

- Michel Parisse: Le Roi de France et son royaume autour de l'an mil, Paris, Picard, 1992.

- Pierre Riché: Les Carolingiens, une famille qui fit l'Europe, Paris, Hachette, 1999

- Yves Sassier: Royauté et idéologie au Moyen Âge, Paris, Colin, 2002.

- Laurent Theis: L'Héritage des Charles, De la mort de Charlemagne aux environs de l'an mil, Paris, Seuil, 1990.

- Yves Sassier: Hugues Capet: Naissance d'une dynastie, Fayard, coll. "Biographies historiques", 14 January 1987, 364 p. online.

Articles

- Xavier Barral i Altet: "Le paysage architectural de l'an Mil", La France de l'an Mil, Paris, Seuil, 1990, pp. 169–183.

- Alexandre Bruel: "Études sur la chronologie des rois de France et de Bourgogne", Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes, n° 141, 1880.

- André Chédeville: "Le paysage urbain vers l'an Mil", Le Roi et son royaume en l'an Mil, Paris, Picard, 1990, pp. 157–163.

- Robert Delort: "France, Occident, monde à la charnière de l'an Mil", La France de l'an Mil, Paris, Seuil, 1990, pp. 7–26.

- Guy Lanoë: "Les ordines de couronnement (930-1050) : retour au manuscrit", Le Roi de France et son royaume autour de l'an mil, Paris, Picard, 1992, pp. 65–72.

- Anne Lombard-Jourdan: "L'Invention du "roi fondateur" à Paris au xiie siècle", Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes, n° 155, 1997, pp. 485–542 online.

- Hervé Pinoteau: "Les insignes du roi vers l'an mil", Le Roi de France et son royaume autour de l'an mil, Paris, Picard, 1992, pp. 73–88.

- Jean-Pierre Poly: "Le capétien thaumaturge : genèse populaire d'un miracle royal", La France de l'an Mil, Paris, Seuil, 1990, pp. 282–308.

- Annie Renoux: "Palais capétiens et normands à la fin du xe siècle et au début du xie siècle", Le Roi de France et son royaume autour de l'an mil, Paris, Picard, 1992, pp. 179–191.

- Laurent Ripart: "Le royaume de Bourgogne de 888 au début du xiie siècle", Pouvoirs, Église et société (888-début du xiie siècle), Paris, CNED, 2008, pp. 72–98.

- Michel Sot: "Hérédité royale et pouvoir sacré avant 987", Annales ESC, n° 43, 1988, pp. 705–733 online.

- Michel Sot: "Les élévations royales de 888 à 987 dans l'historiographie du xe siècle", Religion et culture autour de l'an Mil, Paris, Picard, 1992, pp. 145–150.