Madonna and religion

American singer-songwriter and actress Madonna has incorporated in her works abundant references of religious themes of different religions and spiritual practices, including Christianity (she was raised Catholic), Hinduism, Buddhism, Sufism, and Kabbalah. Several theologians, sociologists of religion and other scholars have reviewed her, while professor Arthur Asa Berger stated that she has raised many questions about religion. Due to her prominent use, an academic described her as "perhaps the first artist of our time to routinely and successfully employ images from many spiritual cultures and multiple religious traditions".

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

Madonna's onstage representations of religions, provocative statements, behavior, among other things, attracted criticism of religious institutions from major religious groups, including the Vatican State/Catholic Church. A handful of clergies, however, reacted with sympathetic views. Various religious adherents staged protests against Madonna numerous times, while she was often accused of sacrilege, heresy, iconoclasm and blasphemy. Madonna herself, has claimed she believes in Jesus but not in institutional organizations.

While the phenomenon goes beyond Madonna, she received solid reviews discussing her religious forays with her ambiguous impact and influence in popular culture across several decades. She was credited with inspiring various scholars from different fields to seek new approaches for works and its religious meanings. Madonna was among the leading public figures often considered an important medium for popularizing ancient spiritual traditions in her generation such as Kabbalah studies or yoga. She became a noticeable trope for the word "icon", according to authors like semiotician Marcel Danesi, with her name appearing in reference works such as the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary or Diccionario panhispánico de dudas to illustrate its new usage in contemporary culture. Outside the religious world, views about Madonna's religious forays varying with different degrees as well, including moderate and conservative perspectives. Illustrating her polarization, some have referred to Madonna as "The Holy Mother of Pop", while Seventh-day Adventist magazine Sings of the Times recalls that some have adopted an alienated view of Madonna as the "Great Whore of Babylon".

Critical scope

The success of Madonna as an international pop star cannot be disconnected from the religious history she created through her relationship to a series of religious authorities—Catholic, Hindu, and Jewish—and who she incited to reply to her ostensible profanations.

—Diane Winston, professor of media and religion (2012).[1]

Shortly after her debut in the 1980s, various cultural analyses of her figure touched on Madonna's religious connotations. Various of them were categorized under her academic mini-subdiscipline, the Madonna studies, which flourished with other topics, according to observers such as Andi Zeisler, Douglas Kellner and Ricardo Baca.[2][3][4] Author and professor Thomas Ferraro notes this early stage, saying "Madonna's impact posed an expressly religious puzzle".[5] She also became a "favorite topic" for religious fundamentalists in her prime.[6] According to editors of Religion and Popular Culture (2016), her video "Like a Prayer" inspired "perhaps more than any other music video scholarly analysis of its religious meanings".[6] On the other hand, other religious studies scholars, like James R. Lewis, have explored Madonna's figure from perspectives that included astrology.[7]

It has also attracted media attention and headlines through the best part of career. In 2018, Cady Lang from Time, commented that there are few figures more closely associated with religion in pop culture than Madonna.[8] Her long-standing relationship with the Catholic Church was noted by publications including Huron Daily Tribune,[9] with Phoenix New Times describing it as a "synonymous with each other" in 2015.[10] Vanity Fair called it a "famously complicated relationship".[11] In 2010, Time magazine included Madonna's moments in their "Top 10 Vatican Pop-Culture Moments"; a rank that shows how the Roman Catholic Church mixed with contemporary culture.[12]

Madonna's religious profile

Madonna's religious background and public display have been extensively detailed.

Catholicism

Madonna is the original and ultimate marriage of celebrity and the Catholic imagination [...] she was the first major popstar to reference symbols that defined a Catholic upbringing

—From a 2018 BBC Culture article[13]

Madonna was born and raised Catholic. She adopted "Veronica" as her confirmation name, paying tribute to Saint Veronica.[14]

Agents like the American theologian Chester Gillis, have explained that Madonna was educated in a strict Catholic household.[15] It influenced and left a mark on both her life and career,[16] with scholar Arthur Asa Berger recalling "the importance of her Italian Catholic background".[17] In 1991, Christian author Graham Cray, wrote for Third Way that Madonna was the only lapsed Catholic in popular music who "has made a reaction against her Catholic background, in her driving force" and as a source of "motivation of her work".[16] Years later, however, French academic Georges-Claude Guilbert commented that "her resentment toward Catholicism is proportional to the marks it left on her", but he didn't feel it as "particularly original", because many writers and artists built entire careers on such ambivalent feelings.[14] To American philosopher Mark C. Taylor, "Madonna's ongoing involvement with Catholicism is exceedingly complex".[18]

Spiritual seeking

Madonna made a major turn in the mid-1990s during her pregnancy. She began practicing yoga and reading spiritual developments coming from Asia such as Hinduism and Buddhism. She also became a Kabbalah devotee.[19] However, she kept her Christian education, revealing that her daughter Lourdes, "will spend more time with the Bible than her television".[20] Religious professor Kathryn Lofton, said that her turn to Kabbalah "inspired articles emphasizing her new spiritual enthusiasm".[21] Erik Davis, considered her case "the biggest metaphysical blast" in a 1999 article for Spin, where he reviewed industry's artists that incorporated or practiced spiritual beliefs.[22] Commentators Craig Detweiler and Barry Taylor called it a "notable turn" in her life, impacted by motherhood, yoga, Kabbalah and Hindu mysticism.[23]

Madonna later adopted the name "Esther", a Biblical Hebrew name that means "star".[24] Shalom Goldman, a Middlebury College professor of religion, quotes Madonna as having claimed to have studied all the women of the Old Testament but she was most drawn to Esther because "she saved the Jews of Persia from annihilation".[25] Some considered the name's choice as a "manifestation of the divine shekhinah" which in Kabbalah denotes the feminine aspect of God's presence.[25] Rabbi Kerry M. Olitzky made the suggestion that Open Source Judaism was what allowed Madonna to develop an interest in Kabbalah without any interest in converting to Judaism.[26]

After her introduction to the Kabbalah studies, Madonna assisted for years to the Kabbalah Centre in Los Angeles,[24] introduced by her friend Sandra Bernhard.[27] The Centre attracted several Hollywood celebrities from Elizabeth Taylor to Britney Spears, but Madonna attracted "bigger headlines" according to Los Angeles Times investigative journalists Harriet Ryan and Kim Christensen.[28][27] In 2011, Reuters explored Madonna's crucial role for Centre's rise, with an insider stating: "Everything changed once Madonna began to study".[29] The centre was "widely associated with its famous member, Madonna" wrote Katherine Stewart.[30] In Jewish Mysticism and Kabbalah (2011), Madonna was described as their most important follower, as she drew "extraordinary publicity to the Kabbalah Centre and induced many people to explore its offering".[31] British author Harry Freedman also called her "the most prominent" Centre's devotee.[32] According to American scientist Peter Gleick, she also made famous their "Kabbalah water".[33]

Into the 2010s, it remained unclear if Madonna kept studying Kabbalah or if she still an active member of the centre. In 2017, a Vice contributor explained that many celebrities, stopped attend the centre or studying Kabbalah.[28] In 2011, British tabloid Daily Mirror and other media outlets, reported that Madonna considered joining Opus Dei, although Spanish newspaper El Confidencial reported it was a hoax.[34] In 2020, editor Pedro Marrero interprets that Madonna has been a spiritual woman who has always try sought God.[35] American director Mary Lambert describes that "Madonna is a very religious person in her own way".[36] Madonna herself, told Terry Wogan, in a 1991 interview, "I'm spiritual, religious".[37] By 2022, she declared that spends some of her time praying for others.[38] She reportedly prays before a stage show, and for what academic Akbar Ahmed called Madonna, the "pop philosopher of postmodernist culture" in the 1990s.[37]

Madonna's religious views, and authors interpretations

- "The God that I believe in, created the world... He/Her/They isn't a God to fear, it's a God to give thanks to"

- The idea that in any church you go, you see a man on a cross and everyone genuflects and prays to him [...] in a way it's paganism/idolatry because people are worshipping a thing"

Besides her spiritual seeking, Madonna has made several statements about religion, and specific denominations. "So many critics seem to love to discuss Madonna's obsession with religion", wrote Fosca D'Acierno in The Italian American Heritage (1998).[41] In this regard, Anne-Marie Korte from Utrecht University, wrote that "religion plays a major role in Madonna's statements and provocations".[42] Author Donald C. Miller, said "she has made very strong verbal and nonverbal statements".[43]

In 2015, in an interview with the Irish Independent, she stated: "I don't affiliate myself with any specific religious group. I connect to different ritualistic aspects of different belief systems, and I see the connecting thread between all religious beliefs".[25] In 2016, she stated that her use of Christian imagery "is just proof of her devotion to Catholicism".[45] She had also criticized their system, saying Catholicism "it's not what God and Christianity are all about".[46]

Canadian professor of religious studies, Aaron W. Hughes, in Defining Judaism: A Reader (2016), interprets that "for Madonna, religion in general and Judaism in particular are inherently divisive and this divisiveness is ultimately responsible for the problems we face".[47] Korte was critical, saying that "Madonna's interest in religion has never been theologically focused: it consists of a combinations of distrust towards institutional religion and an eclectic individual form of spirituality".[42] Catholic author Christopher West, believes that "her reflections on her religious upbringing echo the sentiments of a large swath of the population".[48]

In Fill These Hearts (2013), West quotes Madonna supporting Jesus as a divine being, who walked on the Earth, but she rejects "the religious behavior of any religious organization that does not encourage you to ask questions and your own explorations".[48] Similarly, Christian author Dan Kimball wrote in They Like Jesus but Not the Church (2009), that "Madonna doesn't find anything wrong with the teachings of Jesus" but doesn't believe that "all paths lead to God", citing the problem of religious war.[49]

Implementation in her works

Perhaps the first artist of our time and certainly the most successful to routinely employ facile images from many spiritual cultures and multiple religious traditions is the pop music star Madonna.

—Professor Andrew Tomasello as cited by scholars David Rothenberg and Benjamin Brand (2016).[51]

Religion has influenced Madonna's artistic path; she frequently incorporates religious iconography and themes of different denominations into her visuals and works.[18][52] Cath Martin of Christian Today, wrote she "blurred the lines between art and her own take on religion".[53] Due to her abundant usage, Conrad Ostwalt, a religious studies scholar at Appalachian State University, wrote in Secular Steeples (2012): "Perhaps the most interesting pop star whose work touches upon and implicates religious themes is Madonna".[54]

Catholic iconography has been Madonna's constant.[18] She is credited with even popularizing the cross in pop music as a decorative object, which she uses in her shows and videos.[55] Martin commented that her love affair with the cross "has spanned her music career".[53] As her career continued, she involved Kabbalistic motives in her work and reportedly refused to work on Friday night and Saturday, as a result in her observance of the Jewish Sabbath.[24][56] Religious Jewish symbols and Hebrew letters featured in some of her works, and Madonna was seen numerous times, with the red string around her wrist to ward off the evil eye,[57] a trendy practice among celebrities during Bush era.[28] Among her many other religious references, she included sufism themes.[50]

Madonna often received critics from the community for her provocative implementation of religious in her works. In 2023, she reflected her work as an "artist united people, gave them freedom of expression, unity. It was the mirror of Jesus' teachings", in her understanding.[58] She once also stated about her usage of crosses:

I like crosses. I'm sentimental about Jesus on the cross. Jesus was a Jew, and also I believe he was a catalyst, and I think he offended people because his message was to love your neighbor as yourself [...] He embraced all people, whether it was a beggar on the street or a prostitute, and he admonished a group of Jews who were not observing the prophets of the Torah. So he rattled a lot of people's cages.[25]

Critical observations

.jpg.webp)

A number of theologians noted the abundant use of female religious imagery by Madonna. She has played with female characters and roles from the Christian faith tradition.[42] In The Virgin in Art (2018), Kyra Belán, wrote that she in particular has appropriated of the Virgin Mary, perhaps more than other artist.[59] Feminist theologian Grietje Dresen, argues that Madonna seems to have incorporated very well her Roman Catholic education, in which the beauty, purity, and self-control of the 'immaculate' Virgin Mary are presented to girls as the standard of perfection.[42]

Madonna herself, addressed from her religious education: "I grew up with two images of women, the virgin and the whore".[16] Author and professor Thomas Ferraro, cites celebrities such Mario Puzo and Frank Sinatra as examples of an "Italian pagan" Catholic understanding of power, but he claims Madonna "gave it" a "long-awaited" and much "needed" female valence.[5] On the other hand, her mispronunciation for the astangi in Ray of Light earned criticism of Hindu priests in Benaras and also intrigued some Sanskrit scholars.[60]

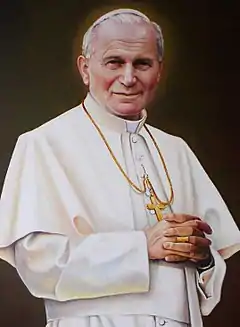

Religious leadership reactions

Madonna has received criticism from religious organizations and leaders of different denominations,[61][62] over the best part of her career. "Madonna has a particular distinction of enraging a variety of religious leaders", wrote Purchase College professor Steven C. Dubin.[63] Alone her 2006 onstage crucifixion, attracted criticism from Christian, Muslim and Jewish leaders.[64][65] About that event, San Francisco Examiner staffers, said "only Madonna could get Muslim, Jewish and Catholic leaders to agree on something".[66]

American philosopher Mark C. Taylor noted Madonna revived a similar longstanding religious criticism on rock and roll, that led representative of the religions charge Madonna as a demonic.[18] In escalated situations, organizations and leaders tried to censure or boycott Madonna.

Christianity

The Vatican State and Popes of her generation condemned numerous of Madonna's acts. During the late-twentieth century, the Catholic Church opposed to her Italian show of the Who's That Girl Tour in 1987, her advertisement with Pepsi in 1989, the Blond Ambition Tour in 1990 or for her first book Sex, in 1992.[67][11][68] Organizations related to the Church, such as the Episcopal Conference of Italy criticized Madonna, and tried to ban her concerts. A parish priest from the organization, denounced Madonna as "an infidel and sacrilegious".[69]

She continued to attract disapproval from Catholic Church in the early years of the 21st century. Vatican representatives questioned her forays with the Kabbalah.[70] With her Confessions Tour, Madonna garnered a major backlash for her segment when she appeared crucified on a giant cross in the countries where the tour was scheduled.[42] Ersilio Tonini speaking with the approval of Pope Benedict XVI, commented "she should be excommunicated".[71] In the 2010s, she was condemned with her Rebel Heart Tour by senior bishops like Patric Dunn from New Zealand, who commented, "There is no question in my mind that some of Madonna's material is highly offensive to Christianity and will be found just as offensive to the majority of people of religious faith", while Singaporean prelate William Goh commented, "There is no neutrality in faith".[71]

Italian Catholicism informs just about everything Madonna does, most often in ways that are not officially sanctioned.

—Thomas Ferraro, Feeling Italian: The Art of Ethnicity in America (2005)[5]

.jpg.webp)

Other leaders and groups from Christian denominations, such as the Baptist Church, have criticized her in addition to the Catholic Church.[73] Ghanaian religious leader Opoku Onyinah described thus "instead yielding to Christian principles, she decided to rebel against everything Christianity stands for".[74] Vsevolod Chaplin from the Russian Orthodox Church, says "I'm absolutely sure that this person needs spiritual assistance" further adding "It's definitely clear for me that all these attempts to use religious symbols also reflect her state of mind and state of soul".[75] American Baptist pastor Jerry Falwell and other conservative Christians leaders found Madonna's wearing religious symbols "trivializing" and "blasphemous" as well.[76] In The Extermination of Christianity: A Tyranny of Consensus (1993) by clerics Paul Schenck and Rob Schenck, her usage of Christian imagery is described as obviously designed to raise the ire of the religious community, twice molesting them by using them as a free promotion.[77]

Other denominations

Madonna attracted the displeasure of Hindu and Jews spiritual leaders.[60][78] Orthodox rabbis also concerned about Madonna, denouncing her for debasing Judaism's deepest mystical tradition,[79] while accusing her of breaking taboos in Kabbalah.[80] Professors of religious studies, Eugene V. Gallagher and Lydia Willsky-Ciollo explained in New Religion (2021), that the Jewish Kabbalah is typically exclusively men and rabbis by trade, but celebrities such as Madonna have taken up the practice under new guise; as a result, both Madonna and Kabbalah Centre attained some criticisms by this conduit.[81] Rabbi Yisrael (Israel) Deri, caretaker of Isaac Luria's tomb (founder of Kabbalah), commented "this kind of woman wreaks an enormous sin upon the Kabbalah".[80][82] Chief Rabbi of Safed (the birthplace of the Kabbalistic tradition), Shmuel Eliyahu in a open letter to Madonna, pointed out that her performances and public behavior were not in keeping with the values of the practice, "the enchanting wisdom you have so much respect for".[25] Rabbi Yitzchak Schochet strongly objected to Madonna's use of the Kabbalah, arguing that it tarnishes Judaism when people who do not observe Jewish law practice Jewish mysticism.[83] A prominent Jewish rabbi from London, also rebuked her practice of Kabbalah.[83]

Jewish leaders condemned a version of "Justify My Love" that incorporated a passage from the Book of Revelation.[63] Rabbi Abraham Cooper blasted the song as dangerous and was worried that fuel antisemitism.[63] Others panned her video "Die Another Day", in which she bound phylacteries to her arm, a Jewish custom usually reserved for men.[79] Madonna enrages Jewish leaders again with the song "Isaac" from her album Confessions on a Dance Floor.[82]

Sympathetic views

Perhaps Madonna's displays of religion and her belief that she 'reeks of Catholicism' is part of God's unfolding will for her to be Madonna, virgin, open and loving, and perhaps mother as well.

—Catholic priest Michael P. Sullivan, Sun-Sentinel (1994)[84]

A handful of religious leaders were sympathetic or neutral towards Madonna's acts, and her artistic representation with religion. Some in the Catholic Church supported it, as British author Lucy O'Brien documented with her onstage crucifixion in 2006.[85] According to Jesuit priest Carlos Novoa, writing for El Tiempo, her crucifixion "is not a mockery of the cross, but rather the complete opposite: an exaltation of the mystery of death".[85] Others like Georges-Claude Guilbert brought the example of Catholic priest Andrew Greeley who "embraced" and "defended" her in the late 1980s.[86][87] "My personal opinion is that Madonna is an artist and, like most artists, uses her experience and understanding of her culture in her work", Presbyterian minister Glenn Cardy said in 2016.[88] On the other hand, Sun Ho, a Singaporean Christian pastor and former singer, praised Madonna's music contribution in the field of dance music in 2006.[89]

In Seeker Churches (2000), author addressed the fact that "seeker church pastors tend to be more sympathetic in their analysis of Madonna's misguided quest for personal fulfillment", as pastor Lee Strobel suggests that Madonna's main problem is neither her "almost sacrilegious use of religious symbols" nor her "morally objectionable behavior", but instead that "she seeks fulfillment in all the wrong places".[90] John W. Frye, citing Strobel in Jesus the Pastor (2010), said his models of teaching move toward "compassion" as in What Jesus Would Say, Strobel "imagines Jesus speaking to Madonna".[91] According to Goldman, some traditional rabbis tolerated Madonna's brand of Kabbalism.[25]

Public reaction

Amid different interpretation of what religion is, Madonna's artistic representations of religion, and statements have the public reacted with varying degrees, even among devotees itself.

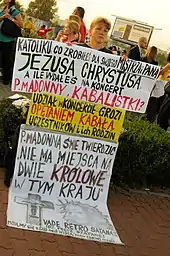

Religious community

.jpg.webp)

Christian community has been described as the religious sector most offended by Madonna.[92] According to Guilbert, in his 2002 Madonna biography, she has been punished by the religious right, such as televangelists and Puritans throughout the years.[73] That sentiment was described by American author Boyé Lafayette De Mente: "millions regarded" her as an anti-Christ because "she is frequently profaning religious symbols".[93] According to American journalist Christopher Andersen, at some stage of her career, she was "across the globe [...] being condemned as a heretic".[94] Catholic priest Andrew Greeley, in The Catholic Myth (1997), summed up that for her detractors, "it is because she has contaminated religion with sex that Madonna must be condemned".[95] According to Seventh-day Adventist magazine Sings of the Times, some have adopted an alienated view of Madonna as the Great Whore of Babylon.[96]

Madonna is virulently criticized by various kinds of Protestants as well as Catholics, and also by Jews [...] Madonna projects the eternal image of the Babylon prostitute.

—French academic Georges-Claude Guilbert, Madonna as Postmodern Myth (2002)[73]

Several Madonna concerts were condemned by prosecutors and religious adherents, including radical Orthodox believers who staged anti-Madonna protests.[68][97] Alone with her 1993 Girlie Show, Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, a Brazilian traditional Catholic activist reported protests and "rebuff" in countries such Germany and Argentina.[98] She angered many Polish religious adherents in various of her stops when she toured.[99] According to Evangelical Times during her Dutch stop of the Confessions Tour, police arrested a 63-year-old priest who admitted to making a hoax call in an attempt to disrupt the event. A bomb threat was also reported.[100]

In 2005, Reuters also informed: She "[...] has drawn frequent censure from ultra-Orthodox Jews who say her embrace of Kabbalah debases their religion".[80] Some of them deemed Madonna as a "depraved cultural icon".[101]

Several religious-targeted publications have written about Madonna's works and her persona. In the 1986 book What about Christian Rock?, authors compared how the religious press called Christian singer Sheila Walsh "sexy", while labeling "porn queen Madonna 'born again'".[102] They also commented on the nickname given to Amy Grant (the "Madonna of Christian Rock"), explaining that other publications picked it up, but when it appeared in the religious press, it offended many Christian readers.[102] "Like a Prayer" topped Religion News Service's 2013 ranking of the "10 'blasphemous' pop songs and music videos".[103] In 2015, Susan Wills of the Catholic website Aleteia stated that Saint Hildegard of Bingen's reputation and fan base "continue to grow eight centuries after her death" and asked, "Does anyone think that will be the case with Madonna?".[104] Susan, and David Mills from the same publication, reviewing her works in 2015, deemed them "so last century" or "so 1980s".[104][105]

| External image | |

|---|---|

After her 2006 Confessions Tour, professor and Catholic author Christine Whelan, wrote an article for Busted Halo (Paulist Fathers), in which ask their readers: "Do I have to go to confession for attending Madonna's Confessions tour?". She received answers from some of them.[108] In January 2023, Madonna sparked outrage among Christians after doing an all-female Last Supper photoshoot, and also for channeling Virgin Mary as Our Lady of Sorrows, on the first Vanity Fair's European "Icon issue".[106][107] The European Conservative headlined, that her photoshoots "Reveals Deep Occult Roots of the Entertainment Industry".[109]

Moderate views: Jock McGregor, a contributor to the evangelical organization L'Abri commented that "not all Christians have been hostile" towards Madonna. McGregor, himself, considered dedicating a few words to Madonna because she is "a significant and representative child of her times".[92] Anglican British writer, Karl Dallas commented at some point that "so far she has done little more than to use the talents God gave her, and challenged a few sensibilities with them".[92] Professor of religion Donna Freitas, and also a Christian adherent, gave a positive commentary to her crucifixion, interpreting "she is performing a woman's right to stand in Jesus's place".[97]

Theological, academic, layman and other responses

The latest atavistic discoverer of the pagan heart of Catholicism is Madonna.

—Social critic, Camille Paglia (1991)[110]

Simultaneous reactions were made by theologians, and other observers.

In Stealing My Religion: Not Just Any Cultural Appropriation (2022), her usage of Catholic aesthetics is understood as an appropriation "to promote her brand".[111] Academic Anne-Marie Korte, similarly states she uses Christian symbols and misuses them to attract attention while showing disrespect for Christian and for religion in general.[42] Commenting about her crucifixion performance in 2006, Lutheran theologian Margot Käßmann was critical, saying "to put oneself in the place of Jesus is an extraordinary manifestation of an inflated ego".[42]

Over years, others have made different interpretations, from a free speech support to more sympathetic views. English academic Katie B. Edwards proposes that "it might be argued that Madonna's use of religious symbols as entertainment is the reason she attracts the strong disapproval of religious institutions". However, she believes "the problem appears to lie more with Madonna's sexuality and the ways in which she uses it during her performances".[112] Media scholar John Fiske once felt and stated that her uses of religious iconography are neither religious nor sacrilegious.[113] Writing for Belfast Telegraph in 2008, Gail Walker brought the scandals that Catholic Church have rocked into comparative, to further express that her "musings on the simple icons of her culture seem more a positive recognition of the emotional power of Christianity than ridicule of it".[114]

In the late-twentieth century, American journalist Pete Hamill even considered her "a good Christian".[46] Behaviorally speaking, in Profiles of Female Genius (1994), editor asserts that "if nothing else, she is honest" with her reflection, making a comparison that "she may be offensive to the Church and appear sacrilegious to most people, but she is more honest than many women seen walking the streets of the world with crucifixes".[117] Journalists Andrew Breitbart and Mark Ebner called Madonna, the "Mother Superior of perpetual self-indulgence".[118] After the release of "Like a Prayer", some religious liberals defended Madonna as a martyr to free speech.[119] Other theologians defended her representations, including her 2006 stage crucifixion, calling a "contribution to feminist theology and liberation theology".[42] Less impressive has been Marcella Althaus-Reid, a contextual theology professor, adopting Madonna's song to refer on materialistic and divine concepts embodied within theological discourses saying: "We are all material theologians living in a material world".[120]

Outside Christian world, some Hindu scholars backed Madonna, including Vagish Shastri after the criticism she faced by religious organizations like World Vaisnava Association with her performance at MTV in 1998.[121]

Metaphor of cult following

.jpg.webp)

Parallel to religious followers' disagreement on Madonna, her figure was a trope for counter-analogous ways, touching the cult status contours. "A figure as disturbing as she is sacred", commented Olivier Bouchara from Vanity Fair France in 2023.[106] The editors of Cassell's queer companion (1995), state that "her remarkable influence [...] is testified by the fact she inspires either intense devotion or revulsion in practically everybody".[122] Broadly speaking, authors of Global Perspectives on Sports and Christianity (2017), explained that in the literature of fandoms, studiers use religious metaphors, as a fan club could be considered a modern and secularized version of a religious group.[123] In The Family, Civil Society, and the State (1998), an insider said "devotion to Madonna and the madonna must be seen as exertions of the same right".[124]

Madonna, star, queen and divinity, but also sometimes scapegoat [...] Goddess and priestess of her own cult, she upsets the adepts of more traditional cults: Christian, Muslims and Jews.

—Georges-Claude Guilbert, in Madonna as Postmodern Myth (2002)[42]

From that analogy, American journalist Ricardo Baca commented in 2008, that for some, Madonna is a "divine creation"—an otherworldly gift to the masses in the form of an incessantly morphing entity who's been steering [...] religious trends [...] for the last 25 years.[2] E. San Juan Jr. cited a biographer who reported in the early 1990s, "millions pray at the altar of Madonna, Our Lady of Perpetual Promotion".[125] In her 2019 novel Tuesday Mooney Talks to Ghosts: An Adventure, Kate Racculia refers to "the altar of Our Lady Madonna Louise of Ciccone", thus telling part of the story of "Dex".[126] Film director David Fincher once described his bond with the singer: "Madonna is my Vatican, she's my Sistine Chapel".[127] Writing for The Guardian in 2010, author Wendy Shanker called Madonna as her guru. She described herself as a fan and not fanatic.[128] In The Power of Madonna, character Sue Sylvester "looks up to Madonna more than any other person, concept, or deity".[129]

Other secularized nicknames were applied. Art historian Kyra Belán explains in The Virgin in Art (2018), that for some, Madonna is "The Holy Mother of Pop", and she adds she "still continuously reinventing and revealing herself in many mundane, divine, mysterious and Madonna-ish ways",[59] while Nick Levine, headlined her in a 2019 Vice's article, as the "Holy Mother of Modern Pop".[130] Professor Abigail Gardner commenting in 2016, said "she has been referred to as a modern pop goddess".[131] Back in 1998, Ann Powers also said she has been designated as a "secular goddess" by audience and pundits.[132] Indeed, La Vanguardia staffers, in the 2015 article, "Madonna: Our Lady of Pop", named her as the "first global goddess of pop".[133] In 2016, Bellevue University psychology professor, Cleveland Evans, called her the "high priestess of pop",[134] and Julián Ruiz in El Mundo called her "Our Lady".[135]

Cultural concerns and discussions

Saudi Arabia, on the other hand, saw no reason to go to war for Madonna, whom many Islamic clergymen regarded as a worse threat than Saddam.

—The New Leader (1995).[136]

.jpg.webp)

Due a solid popularity, Madonna's forays with religion imposed cultural concers over decades among the community. Authors Peter Levenda and Paul Krassner concurred that probably no person of the 1980s and 1990s in the American popular culture represents better the conflicting spiritual forces that Madonna.[137] "Some of the most important and interesting texts in recent U.S. culture which have overlapping concerns with liberations theologies are by Madonna", wrote religious scholar Mark D. Hulsether, in Bruce Forbes's Religion and Popular Culture in America.[138] Academic Akbar Ahmed commented that in the cases of Rushdie and Madonna, "numerous overlapping national, intellectual and cultural boundaries are being crossed".[139]

In 2002, H. T. Spence from Foundations Bible College, decried that although the world has written her up as being very philosophical and theological in her presentation, "she is the factual commentary that America has come to a cultural illiteracy".[140] Stephen Prothero, put Madonna in context of his interpretation in Religious Literacy (2009), that "many cannot recognize the phrase 'Hail, Mary', except as the name of a football play", and that many are "unaware that the pop singer Madonna was actually named after someone".[141] In Madonna as Postmodern Myth (2002), French academic Georges-Claude Guilbert captures and perceived a related feeling by saying, "today, America knows more about Madonna than about any passage of the Bible".[142] Sociologist Bryan Turner, reviewed Ahmed's words and his emphasis on Madonna saying:

Madonna [...] is the sign of postmodernism, which is a threat simultaneously to manhood and to truth. However, if Ahmed wants to defend Islam against the threat of a castrating Madonna, then the implication is that Islam is yet another grand narrative which requires protection from the sexual and cultural diversity represented by Madonna (and others) [...] Ahmed is probably right (in one sense): the threat to Islam is not the legacy of Jesus, but that of Madonna.[143]

Madonna also became one of the Hollywood celebrities that attracted concerns from authors about her spiritual forays. For example, British commentator Melanie Phillips, said that Madonna, Cherie Blair and Princess Diana represent the rise of what Christopher Partridge has termed "occulture".[144] Robert Wuthnow, a studier of sociology of religion, described in Creative Spirituality: The Way of the Artist (2003): "At worst, artists' spirituality is reduced to the commercial exploits of pop-singer Madonna or the cultic followings of the Grateful".[145] In Mediating Faiths (2016), Joy Kooi-Chin Tong wrote that Madonna, Microsoft and McDonald's, represented a "fierce competition" for religious leaders in Singapore to retain their followers' loyalty.[146] Following the release of "Justify My Love", there was a report of graffiti in at least three synagogues and a high school in Ventura County, California, using the phrase "synagogue of Satan" (Revelations 2:9).[147]

Israeli visits and role within Kabbalah studies

Madonna concerned Israelis and Palestines, during a massive infiltration of the Kabbalah into the public eye.

Madonna attended a Kabbalah lecture in Israel during the 2004 Jewish New Year. Her decision to visit Rachel's Tomb was criticized by pro-Palestinian activists, and some protests were made.[148] Agence France-Presse (AFP), informed that she raised questions over the nature of her faith.[57] Professor Goldman, commented she received an overwhelming amount of media and government attention, resulting in "unforeseen diplomatic consequences".[25] As a result, Egypt banned Madonna from visiting their country.[25] In an article for The Guardian, Chris McGreal described how Orthodox men chanted shabbos while others yelled at her to go home, accusing Madonna of desecrating their religion.[79] The Jewish agency International Society for Sephardic Progress requested to Yitzhak Kaduri —the maximun authority of Kabbalah in his time— refuse to bless the singer.[149] Kaduri flatly refused to see Madonna on her pilgrimage to Israel.[150]

The media were also divided. The Jerusalem Post described her as "an open philo-Semite who has done more than many Jews". Giving Madonna and her embrace of Kabbalah the benefit of the doubt, the Post staff declared: "Perhaps Madonna will lead some Jews and others astray and give a rich and sophisticated branch of Judaism a bad name. Perhaps, however, some of the many Jews and others who seek spirituality and community in other quarters, such as Eastern religions, will be inspired to explore what Judaism has to offer".[25] An English-language program in Safed, claimed "Madonna happened to be a vehicle for God".[25] American-born Israeli journalist Yossi Klein Halevi, wrote that for some Jews, "Madonna's endorsement of Jewish mysticisms helps make Judaism attractive to alienated young Jews".[151]

Her public role within the Kabbalah studies earned her some criticism. Scholars from the University of Northern Iowa criticized Madonna for turning the multi-thousand year old religious study into entertainment.[56] Kabbalah itself has also raised concerns; British commentator Melanie Phillips described Madonna as an icon of Western modernity and the world's most famous proponent of Kabbalah, which she argues is a "modern perversion" of a branch of Jewish mysticism.[144] Other Madonna's visits to Israel for her Kabbalah agenda were reported, but with no major concerns.[26] On the other hand, Rabbi Kerry M. Olitzky believes that her interest in one form of Jewish philosophy spilled over into advocacy for the land of Israel.[26] In 2009, Madonna wrote an article for Yedioth Ahronoth discussing Jewish faith.[152]

Madonna and dichotomy

The central dichotomy she inevitably invokes is that of the virgin and the whore [...] Indeed, many critics have taken her use of religious imagery to be a prime example of what Fredric Jameson calls "blank pastiche": the symbols are seen as detached from their traditional contexts and thus as ceasing to signify.

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

British academic Helen Weinreich-Haste once noted Madonna's mix of religion and sexuality, saying that "much has been written about her subversive effect on middle-class and Catholic values.[69] She is one of the world's first performers to "manipulate the juxtaposition of sexual and religious themes", said business theorist Jamie Anderson.[154] Donald C. Miller, considered is "something that set her apart from earlier female performers".[43]

In The Virgin in Art (2018), Kyra Belán felt that she "has successfully fused these antisexual archetypes and made them sexy, a feat not previously achieved by anyone else".[59] Author of Transgressive Corporeality (1995), said that Madonna created "a religion of the simulacrum" by mocking the traditional meaning of the symbols of Catholicism, and reducing them to vehicles for the evocation of sexual feeling.[155] Theologian Robert Goss was overall positive with Madonna's religious "rebellion", considering her even a "Christ icon", who "has dissolved the boundaries between queer culture and queer faith communities" (also known as gay religion).[156]

In Kabbalah and Modernity (2010), by professors of religious studies Boaz Huss, Kocku von Stuckrad and researcher Marco Pasi, it is stated that "from the beginning Madonna has presented herself as saint and virgin on the one hand, and as a sinner with inclination to promiscuity" and more that any other artist, Madonna plays with these roles and this way, most interpreters agree she is the "icon" of postmodern self-fashioning.[24] Semiotician Marcel Danesi commented that "perhaps no one has come to symbolize the sacred vs. profane dichotomy more than Madonna".[157]

She inscribed her own view of sin exploring her sexuality and religious themes and it influenced others. For example, professor Peter Gardella, wrote in Innocent Ecstasy (2016), that "her music helped others to reach the same goal". Gardella, further quotes a professor of gender studies as saying: "It was also Madonna, leading her own sexual revolution, who made me realize that sex was not a sing, nor was it a bad thing, in spite of what the Catholic Church and my family thought".[61] Miller, another supporter of these views, noted her early influence in a substantial number of teenage girls, as Madonna impacted not only their fashion, but their identities and influencing on their life goals and desires.[43]

Other Madonna's acts were analyzed. M.C. Bodden, an early modern English professor at Jesuit institution, Marquette University, explored the "Madonna prayer" in the film Truth or Dare.[158] Bodden suggested because that scene was replayed hundreds of times in different cities and countries, "Madonna has constituted a new identity for prayer", although it lacks of religiousness.[158] Bodden further describes it as a "floating signifier" that follows what Baudrillard calls "four orders".[158] Sociologist Bryan Turner, as is cited in Religious Commodifications in Asia: Marketing Gods (2007) illustrates:

[...] Popular culture constantly appropriates religious symbols and themes, and that these commercial developments are paradoxical, because they both contribute to the circulation of religious phenomena, but at the same time they challenge traditional, hierarchical forms of religious authority. Madonna in many ways is the principal example of these developments, since she is simultaneously an ironic and iconic figure.[159]

Impact in popular culture

- "Since Madonna's time in the media spotlight, we are several cultural cycles removed from the idea that traditional religious imagery points directly and unambiguously to the divine"

- "Madonna's use and manipulation of Christian symbolism unleashed a new trajectory of meanings and associations for those symbols quite outside the control and purview of institutional religious authority, much to the chagrin of religion leaders"

Scholars in Queer Religion (2011) and Media Events in a Global Age (2009), .[160][161]

American professor Arthur Asa Berger described that she has raised many questions about religion.[162] The advent of music video "Like a Prayer" marked alone, to inspire "leading" cultural studies theorists, musicologists, and philosophers, from Susan McClary to Mark C. Taylor to explore new ways of addressing works' religious meanings.[6]

Less impressed have been the authors who compared the influence of popular culture as a whole with a perceived decline of some religious ideologies, or particularly Catholicism, but put Madonna within the cultural industry. In Edward Said and the Religious Effects of Culture (2000), William David Hart, addressed Edward Said and Theodor W. Adorno perspectives of ideologies. He uses the singer, as many people know about her, but "have not a clue" about who the Sistine Madonna is.[163] Joel Martin in Screening The Sacred (2018), also said that religion has become a simple one topic, and not a particularly one. He perceives that critics, seem to assume that religion has declined in importance in the modern age of advanced capitalism, and the critical action is elsewhere—with Madonna, not the madonna—.[164] Graham Howes, a sociologist of religion, explored in The Art of the Sacred (2006), the "altered" meanings, describing "a strong case could be made for the dominant imagery of contemporary Western culture being neither primarily visual nor verbal but essentially audiovisual —the singer Madonna, rather than the madonna—.[165] In Changing Fashion (2007), authors discussed while mentioned Madonna, that in value systems of modern culture, "nothing is sacred, everything is marketable".[56]

Entertainment industry

In 1999, Erik Davis considered Madonna as "just the tip of the iceberg" in his description that "pop music has always percolated with weird religious energies".[22] For British-Australian sociologist Bryan Turner, popular religion became a component in the industry and Madonna "is the most spectacular illustration of this process", he said.[168] Australian music journalist Craig Mathieson, wrote for The Canberra Times that "it was Madonna who summed up the way pop music intertwines the secular and spiritual".[169]

Cady Lang from Time stated in 2018, her "obsession with her Catholic upbringing has undeniably shaped both the pop culture and fashion landscape".[170] "For the first time in mainstream culture", she brought religious symbolism into pop music, said Gail Walker from Belfast Telegraph.[114] Stewart Hoover, a scholar of religious studies, asserts that Madonna "pushed new boundaries in bringing traditional religious imagery into the popular music context".[171] Some perceived an influence on other entertainers; according to Nelson George, Blackout by Britney Spears "contains some direct Madonna references", with the CD booklet photo showing Spears sitting on a priest's lap.[172] In decrying Gaga's mimicry of Madonna, Bill Donohue president of the US Catholic League acknowledges that "religious" symbolism already has an autonomous, secular system of meaning in popular culture.[161] Catholic theologian Tom Beaudoin, whom described Madonna's "Like a Prayer" video as "irreverent spirituality",[173] argues in Virtual Faith (1998) that "pop music has become the amniotic fluid of contemporary society. It is the place where we work out our spirituality".[23]

Fashion

Lynn Neal, assistant professor of religious studies at Wake Forest University, wrote in Religion in Vogue (2019), that despite the criticism from the Christian community towards Madonna, others found her early rebellious stance to conservative religion and her juxtaposition of religious symbols with female sexuality "fashionable" and sought to emulate her style.[76] In Consumption and Spirituality (2013), academic Linda M. Scott and the other authors, credited Madonna with initiating the trend of using religious emblems typically worn as objects of beauty.[174] The Globe and Mail's Nathalie Atkinson was critical, granting Madonna a major role because religious iconography became "subversive" for the masses since the 1980s, while her style infiltrated high fashion.[175]

Madonna made a significant impact regarding the usage of crucifixes as a fashion item over years, with Christian writer Graham Cray describing in 1991, how "she has made the crucifix a fashion icon".[16] Vogue Italia's Laura Tortora, even thought Madonna was the first to wear crucifixes as fashion accessories.[176] Neal mentioned previous examples, but they generated little comment and controversy in either the secular or religious press.[177] Due to Madonna's popularity, Neal said "the most credit" for the popularity of cross jewelry could go to Madonna, further citing an industry insider, who said her cross "had a noticeable impact".[76] Academics have documented the cross-shaped jewelry inspired by Madonna, might be understood as "a religious symbol that has overtaken the culture".[178] Her massive appeal, and usage was controversial in her time; in 1985, minister Donald Wildmon called her "anti-Christian" and "antifamily" for wearing crucifixes as jewelry.[179] Others accused her as "a source of moral contagion" to children and families.[180] Revisiting the era, Stephanie Rosenbloom from The New York Times, wrote in her article Defining Me, Myself and Madonna (2005) how her commitment to Madonna, and not Roman Catholicism moved her to petition for a cross to her parents.[181] Writing for Vanity Fair in 2019, Osman Ahmed, commented positively saying "many of today's" jewelers look to the magpie mash-up of the New Romantics and Madonna in her Like a Virgin phase.[182]

In 2004, BBC informed that after Madonna's use of red string, other celebrities followed suit, such as Britney Spears and Courtney Love,[148] although other adopters were Michael Jackson, Demi Moore and Lindsay Lohan.[183] The red bracelet also saw a surge in sales, with Madonna having been an influence.[184]

Spiritual practices/traditions

Associate professors in Religion and Popular Culture: Rescripting the Sacred (2016), explained that she has been giving credit for opening up new ways to experience and express spirituality and religion.[6] In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Religion and Popular Music (2017) by Christopher Partridge and Marcus Moberg, Madonna is credited with ushering Indochic, and the resignifications of Hindu symbols like the bindi and henna, practices like yoga, meditation and the language Sanskrit as "fashionable and cool" in her generation.[60]

Madonna was among the leading celebrities in popularize the Kabbalah studies.[185][186][187] Karen Stollznow, an Australian writer commented that she made it "trendy" in Occident.[188] Author Alison Strobel commented that "Madonna had popularized it to the point where it was simple to find a place to go learn".[189] By 2015, American educator and theologian Robert E. Van Voorst remarked Internet searches for "Madonna" and "Kabbalah" returning more than 695,000 hits on February of that year, and which led him to conclude it "remains strong".[83]

Other publications have particularly explored Madonna's role for bringing yoga to the masses in her generation; from The New York Times to Diario Sur, placing her on frontline compared to others.[190][191] These sources have exemplified the previous stereotype associated with the subcultural group of hippies.[191] While they were not pleased, in 2004 the Yoga Journal cited a program from E! in which yoga was understood as part of a counterculture and did not officially become a trend followed by the masses until Madonna took it up.[192] In Women, Body, Illness (2003), Madonna is credited with popularizing Ashtanga Yoga as a way to blend spiritual awareness with body fitness.[193] However, yoga guru Sadhguru, was overall critical about textbooks and other sources giving credit to figures like Madonna, and not Shiva (Adiyogi).[194]

Meaning of "icon"

The term "iconography" would pass into high culture, and later in the twentieth century, into popular culture, where "icon" refers to a secular celebrity such as Madonna.

—Historians Asa Briggs and Peter Burke (2009).[51]

Madonna represented a meaningful road for the word "icon", of religious overtones, in popular culture usage. Universität Heidelberg professor of American literature, lumped Madonna with other three examples as "obvious" illustrations of "cultural icon", further citing Oxford English Dictionary's 2009 definition of "icon".[195] "Thus, if researchers, journalists, or everyday conversationalists were to call [...] Madonna a cultural icon, they may not be saying just that she is a striking image but that as a culture, we have invested her with a sacred status that any of her images carry", wrote author of Sexualities and Popular Culture (1998).[196]

In Language, Society, and New Media: Sociolinguistics by semiotician Marcel Danesi, is documented that the word "icon" is a "term of religious origin" and "arguably used for the first time in celebrity culture to describe the American pop singer Madonna".[197] The following description asserts that this word is "now used in reference to any widely known celebrity, male or female".[197] Madonna's name is even used as an illustration of its new meaning in reference works such as the Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary and Diccionario panhispánico de dudas.[198][199] Having mentioned the case of Madonna, Guy Babineau from Xtra Magazine stated in 2008: "I'm old enough to remember when people weren't called icons".[200]

Over years, while also mentioning Madonna and although some of them reacted no impressive, a number of scholars have illustrated how the word became more popular for cultural terms, instead of religion and art history, including Keyan Tomaselli and David H. T. Scott in Cultural Icons (2009),[201] and authors of Handbook of Research on Consumption, Media, and Popular Culture in the Global Age (2019), where the analogy between Madonna and the Virgin Mary were compared.[202]

Background and author interpretations

Danesi, said that calling Madonna an "icon" was also a result of the irony of her name.[197] "Her face matches her name [...] she really look like a madonna", wrote the interviewer of arguably her first-ever press article (1978), from The Charlotte Observer.[204]

Madonna "appeared as challenging twentieth-century image of an ancient icon", wrote Lucy O'Brien in Madonna: Like an Icon.[205] In a similar connotation, professor Abigail Gardner wrote in Rock On (2016), "she has appeared as a modern incarnation of an ancient icon".[131] Even, associate professor Diane Pecknold, in American Icons (2006), explored that "many contemporary observers contended that from the very beginning of her career, Madonna's main ambition was to become an icon and that pop music simply provided the most convenient avenue for attaining that goal".[206] For Madonna, as Rodrigo Fresán quotes, an icon is when people start to unrealistically identify with them or hate for "all the wrong reasons".[207] In the 1990s, scholar Camille Paglia called her an "important icon",[208] while Rolling Stone staffers, named her a "living icon".[209] In the mid-2010s, Naomi Fry copy chief of T: The New York Times Style Magazine deemed her the "most iconic of icons",[210] and Erica Russell from MTV commented that she has both defined and redefined what it means to be an icon.[211]

Depictions

"Religion appears in popular culture and popular culture appears in religion", according to the editors of The Columbia Documentary History of Religion in America Since 1945 (2005).[178] As reported medievalists Richard Utz and Jesse G. Swan, in The Year's Work in Medievalism, 2002, Madonna is mentioned in Supernatural Visions (1991), where she is described as "both the incorrigible Whore of Babylon and the simple sinner".[212] In 2014, a group of Christians released the book Madonna's new age end time Satanism: A revelation. One of its authors, Stacey Dames, a self-declared former Madonna's fan and blogger from The Christian Post, devoted a same-titled article in 2012. Some media outlets referred to the group as Christian fanatics and Dames was called a "Madonna-obsessed".[213][214] An assistant art professor from the University of Tampa, used Madonna and Elvis Presley in an Italian exhibition to show parallels between the Virgin Mary and Jesus respectively, and how popular culture "is becoming a religion for some people".[215]

Madonna was name-checked in some religious dialogues. Shaul Magid, a religious scholar, wrote in American Post-Judaism (2013), heard about rabbis in Reform and Conservative synagogues citing in their discourses Homer, Plato, Buddha, Muhammad, Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., the Dalai Lama and even Madonna.[216] "This is as if we tried to enter into a dialogue with Catholics, and for this purpose we invite the Pope and pop star Madonna", echoed German academic Christian Joppke from a religious Muslim leader, objecting to the participation of feminist Muslim critics at the first German Islam Conference in September 2006.[217]

Italian Ursuline nun, Sister Cristina made her musical debut in 2014, covering the song "Like a Virgin", as "a testimony of God's capacity to turn all things into something new".[218] In an interview with Catholic daily L'Avvenire, she further expressed that she made it "without any intention of being provocative or scandalous", as well as applying spiritual variety. SIR, a news agency run by Italian Bishops, commented about Madonna posting a photo with the nun as a sign of endorsing Sister's cover, but they interpreted the image saying that Sister Cristina needs to be "careful" since her choice of cover can easily be "manipulated".[219][218] She later gave a copy of her album to Pope Francis.[9]

See also

- "Illuminati" (Madonna song)

- Madonna and contemporary arts

References

- Winston 2012, p. 427

- Baca, Ricardo (November 5, 2008). "25 questionable things about Madonna". The Denver Post. Archived from the original on February 10, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2022.

- Zeisler 2008, p. online

- Benstock & Ferriss 1994, p. 163

- Ferraro 2005, pp. 152–153

- Santana & Erickson 2016, pp. 90–92

- Lewis 2003, p. 712

- Lang, Cady (May 4, 2018). "15 Times Catholicism Inspired Iconic Fashion Moments". Time. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- "In Philadelphia, Madonna gives 'Popey-wopey' her blessing". Huron Daily Tribune. Associated Press. September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Keil, Jason (October 19, 2015). "Madonna's Love/Hate Relationship With Catholicism". Phoenix New Times. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Bryant, Kenzie (May 6, 2018). "How Madonna Interpreted Catholicism at the Met Gala". Vanity Fair. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Romero, Frances (October 20, 2010). "Top 10 Vatican Pop-Culture Moments: Madonna, Over and Over". Time. Retrieved September 14, 2022.

- Smith Galer, Sophia (May 3, 2018). "Is it okay to hijack Catholic style?". BBC. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Guilbert 2015, p. 92

- Gillis 2009, pp. 108–109

- Cray, Graham (July–August 1991). "Post-modernist Madonna". ThirdWay. pp. 8–10. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Berger, Arthur Asa (2018). Perspectives on Everyday Life. Palgrave Pivot. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-99795-7_27. ISBN 978-3-319-99794-0. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- Taylor 1993, pp. 191–192

- Morgan 2015, p. online

- MTV News Staff (January 6, 1997). "Madonna Doles Out Mothering Tips". MTV. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- Lofton 2017, p. 134

- Davis, Erik (January 1999). "The God Squad". Spin. Vol. 15, no. 1. p. 86. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Detweiler & Taylor 2003, p. 130

- Huss, Pasi & von Stuckrad 2010, p. 293

- Goldman 2019, pp. 158–163

- Olitzky 2013, p. 38

- Ryan, Harriet; Christensen, Kim (October 18, 2011). "Celebrities gave Kabbalah Centre cachet, and spurred its growth". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- Marthe, Emalie (May 21, 2017). "Why Celebrities Stopped Following Kabbalah". Vice. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- Molloy, Tim (December 14, 2016). "The Kabbalah Center: how crucial was Madonna to its rise?". Reuters. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Stewart 2012, p. online

- Greenspahn 2011, p. 180

- Freedman 2019, p. xi

- Gleick 2010, p. 133

- Religion Confidencial (April 12, 2012). "La historia de la falsa visita de Madonna a un centro del Opus Dei en Londres. El 'Daily Mirror' publicó un bulo el lunes". El Confidencial. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- Marrero, Pedro (August 24, 2020). "Madonna's Relationship with Kabbalah — inside Her Religious Views over the Years". AmoMama. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- O'Brien 2018, p. 192

- Ahmed 2004, p. 217

- Power, Shannon (October 13, 2022). "Madonna Spends 50% of Her Day 'Praying for People'". Newsweek. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- "Madonna gets her wrist inked with a Kabbalah symbol". Geo TV. March 14, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- Bentley, Cara (June 29, 2019). "Madonna says she wants to challenge the Pope on Jesus' view on abortion". Premier Christian. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- D'Acierno & Leonard 1998, p. 495

- Buikema et al. 2009, pp. 117–130

- Miller 2018, p. 202

- Walls, Jeannette (November 6, 2006). "Has Madonna become a Jew for Jesus?". Today. Retrieved March 4, 2023.

- Ong, Czarina (December 14, 2016). "Madonna Talks About Catholic Church Excommunication, Says She Wanted to Become a Nun". Christian Today. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Sexton 1993, pp. 235–236

- Hughes 2016, p. 7

- West 2013, p. 17

- Kimball 2009, p. online

- Nair-Venugopal 2012, p. online

- Brand & Rothenberg 2016, p. 293

- Laderman & León 2003, p. 403

- Martin, Cath (December 5, 2014). "Madonna on prayer: It 'isn't a religious thing'". Christian Today. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Ostwalt 2012, p. 252

- Andersen & Gray 2008, p. 106

- Lynch & Strauss 2007, p. online

- "The Kabbalah of Madonna - ancient Jewish mysticism or New Age mumbo-jumbo?". The Namibian. Agence France-Presse. August 13, 2004. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Iftikhar, Asyia (January 23, 2023). "Madonna calls out Catholic Church over 'hypocritical' attacks". PinkNews. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

- Belán 2018, p. online

- Partridge & Moberg 2017, p. online

- Gardella 2016, p. 163

- "Madonna supported by Jewish, Hindu communities". The Hindu. August 29, 2009. Retrieved October 24, 2022.

- Dubin 2013, p. 83

- "Religious leaders slam Madonna stage crucifixion". The Globe and Mail. August 4, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Donohue, Bill (August 4, 2006). "Madonna's Toilet Fetish Proves Revealing". Catholic League. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Examiner Staff (August 4, 2006). "Scoop! Madonna goes retro, angers religious leaders". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Morrison 2009, p. 42

- "Madonna ignores plea to tone down act". The Sydney Morning Herald. September 13, 2006. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Weinreich-Haste 1993, p. 174

- Worden, Mark (August 4, 2006). "Religious Groups Blast Madonna". Billboard. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Guardian music (March 4, 2016). "Madonna is 'highly offensive to Christianity', says New Zealand bishop". The Guardian. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Whiteley 2013, pp. 187–188

- Guilbert 2015, p. 163

- Onyinah 2022, p. 32

- Knobel, Beth (September 12, 2006). Faber, Judy (ed.). "Madonna Makes Russian Debut". CBS News. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Neal 2019, p. 111

- Schenck & Schenck 1993, p. 91

- Abanes 2009, p. online

- McGreal, Chris (September 20, 2004). "Madonna in mystical mode dismays Orthodox Jews". The Guardian. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- "Jewish mystics to Madonna: Lay off our sage!". Today. Reuters. October 9, 2005. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Gallagher & Willsky-Ciollo 2021, pp. 416–417

- Silverman, Stephen M. (October 10, 2005). "Madonna's Song Enrages Jewish Leaders". People. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Van Voorst 2016, p. 216

- Sullivan, Michael P. (October 30, 1994). "Madonna's use of symbols may be divinely inspired". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- O'Brien 2018, p. 447

- Guilbert 2015, p. 166

- Forbes & Mahan 2005, p. 77

- Klimecki, Lawrence (March 18, 2016). "Madonna, the Archbishop, and the Duty of the Art Patron". Catholic Church in Singapore. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Lay, Belmont (February 24, 2016). "In 2006, Sun Ho said she loves Madonna". Mothership. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Sargeant 2000, p. 90

- Frye 2010, pp. 89–90

- McGregor, Jock (2008). "Madonna: Icon of Postmodernity" (PDF). L'Abri. pp. 1–8. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 7, 2010. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- Lafayette De Mente 2005, p. 71

- Andersen 2015, p. 252

- Greeley 1997, p. 282

- Peckham, Kym (June 1, 2017). "The Scarleth Woman of Revelation". Signs of the Times. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- Block, Melissa (August 16, 2008). "Madonna's Cross Raises Thorny Questions". National Public Radio (NPR). Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- Corrêa de Oliveira, Plinio (November–December 1993). ""Madonna" Is Rebuffed in Argentina". Tradition, Family, Property (TFP). pp. 9–10. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- MTV News Staff (July 19, 2012). "Madonna Avoids Another "'MDNA' Tour" Controversy by Agreeing To Show Clip Honoring Polish War Veterans". MTV. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- ET staff writer (September 30, 2006). "Madonna". Evangelical Times. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- "Para los rabinos, Madonna es un "depravado ícono cultural"" (in Spanish). Infobae. August 10, 2004. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- Peters, Peters & Merrill 1986, p. 92

- Pellot, Brian (November 1, 2013). "From Madonna to Lady Gaga: 10 of the most 'blasphemous' pop songs and music videos". Religion News Service. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Wills, Susan E. (October 2, 2015). "Madonna's Demons, the President's PSA and Other Grammy Oddities". Aleteia. pp. 1–2. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Mills, David (August 25, 2015). "Madonna: Stripper Nuns Don't Make You Interesting". Aleteia. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Bossinakis, Charisa (January 18, 2023). "Madonna sparks outrage with Christians after doing Last Supper photoshoot". UNILAD. Retrieved January 19, 2023.

- Cromos (January 25, 2023). "Madonna posa como la Virgen María y causa polémica". El Espectador (in Spanish). Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- Whelan, Christine B. (August 4, 2006). "Have I Sinned?". Busted Halo. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- Bentz, Jan (February 9, 2023). "Madonna's Photo Shoot Reveals Deep Occult Roots of the Entertainment Industry". The European Conservative. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- Ivins, Molly (September–October 1991). "I Am the Cosmos". Mother Jones. Vol. 16, no. 5. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Bucar 2022, p. 15

- Edwards 2015, p. 122

- Fiske 2006, p. online

- Walker, Gail (August 19, 2008). "Why we're all still so hung up on Madonna". Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Smith, Liz (May 25, 2006). "Madonna's 'Confessions' concert: good, if over the top". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on June 18, 2006. Retrieved May 15, 2022.

- Bellafante, Ginia (November 23, 2006). "A tribute to Madonna's current and former selves". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 23, 2021. Retrieved September 23, 2021.

- Landrum 1994, p. 275

- Breitbart & Ebner 2004, pp. 117–118

- Judge 2010, p. 104

- Greenough 2017, p. online

- "Some Hindu Scholars Back Madonna". Associated Press. September 28, 1998. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Stewart & Hamer 1995, p. 158

- Adogame, Watson & Parker 2017, p. online

- Wolfe 1998, p. 122

- E. San Juan Jr. 2002, p. 86

- Racculia 2019, p. 323

- Andrews 2022, p. online

- Shanker, Wendy (May 10, 2010). "Madonna is my guru". The Guardian. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Wilson 2011, p. 318

- Levine, Nick (June 13, 2019). "The Guide to Getting Into Madonna, Holy Mother of Modern Pop". Vice. Retrieved September 23, 2022.

- Gardner 2016, p. online

- Powers, Ann (March 1, 1998). "Pop View; New Tune for the Material Girl: I'm Neither". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 4, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- Ramos, Rafael (April 1, 2015). "Madonna: Nuestra Señora del pop". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- Evans, Cleveland (August 16, 2016). "'Madonna' as a name is never in vogue". Omaha World-Herald. Archived from the original on July 18, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2022.

- Ruiz, Julián [in Spanish] (November 19, 2013). "Santa Madonna, 'ora pro nobis'". El Mundo (in Spanish). Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- "Report". The New Leader. Vol. 78. 1995. p. 10. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- Levenda & Krassner 2011, p. online

- Forbes & Mahan 2005, p. 75

- Ahmed 2004, p. 220

- Spence 2002, p. 106

- Prothero 2009, p. online

- Guilbert 2015, p. 89

- Turner 2002, pp. 14–15

- Phillips 2011, pp. 1, 3

- Wuthnow 2003, p. 6

- Redden 2016, p. 159

- Merkl 2019, p. online

- "Madonna attends Kabbalah lecture". BBC. September 16, 2004. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- "Jewish agency calls upon prominent rabbi to reject blessing pop star Madonna". Cision. April 22, 2004. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- Martin et al. 2008, p. online

- Halevi, Yossi Klein (September 24, 2004). "Madonna and the Kabbalah Cult". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Murray, Robin (July 30, 2009). "Madonna Writes Of Jewish Faith". Clash. Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- McClary 2017, p. 228

- Anderson, Jamie; Kupp, Martin (December 1, 2006). "Entrepreneurs on a dancefloor" (PDF). London Business School. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 7, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- MacDonald 1995, p. 134

- Goss 2007, pp. 178–179

- Danesi 2010, p. 141

- Bodden 2011, p. online

- Kitiarsa 2007, p. 32

- Couldry, Hepp & Krotz 2009, p. online

- Boisvert & Johnson 2011, pp. 219–220

- Berger 2002, p. 108

- Hart 2000, p. 37

- Martin 2018, p. online

- Howes 2006, p. 65

- Haris, Ruqaiya (October 27, 2021). "Lil Nas X and the New Era of Religious Symbolism in Music". Another Magazine. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- George, Tom (July 7, 2022). "The rise of the blasphemy bop". Vice. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- Turner & Khondker 2010, p. 74

- Mathieson, Craig (January 29, 2016). "Album Reviews". The Canberra Times. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Lang, Cady (2018). "Let Madonna Take You to Church With Her Crazy Surprise Met Gala Performance". Time. Archived from the original on June 23, 2022. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- Hoover 2006, p. 50

- George & Carr 2008, p. online

- Ward 2019, p. online

- Rinallo, Scott & Maclaran 2013, p. 10

- Atkinson, Nathalie (April 6, 2018). "Exploring the Catholic influence on fashion, from Madonna's Like a Prayer to the runway". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- Tortora, Laura (August 1, 2018). "Madonna's Most Iconic Looks". Vogue Italia. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Neal 2019, pp. 90–91

- Harvey & Goff 2005, p. 321

- Schwichtenberg 1993, p. 23

- Cross 2007, p. 83

- Rosenbloom, Stephanie (November 13, 2005). "Defining Me, Myself and Madonna". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 18, 2022. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Ahmed, Osman (January 16, 2019). "The Storied History of Jewellery and Religion". Vanity Fair. Retrieved September 10, 2022.

- Moore 2015, p. 28

- Lynch & Strauss 2007, p. 1

- Sickels 2013, p. 376

- Arjana 2020, p. online

- Wilkinson, Rachel (April 5, 2007). "K Is for Kabbalah". The Independent. Archived from the original on August 30, 2008. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- Stollznow 2014, p. online

- Strobel 2011, pp. 108–109

- "60 Times Changed Our Culture". The New York Times. August 16, 2018. Archived from the original on July 22, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- Miñana, Fernando (October 19, 2015). "La invasión del yoga". Diario Sur (in Spanish). Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- "Media Sutra: Yogatainment". Yoga Journal. No. 183. September–October 2004. p. 159. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Moss & Dyck 2003, p. 178

- "Recognizing the Adiyogi". Isha Foundation. January 9, 2017. Retrieved September 12, 2022.

- Leypoldt, Günter. "Introduction: Cultural Icons: Charismatic Heroes, Representative Lives" (PDF). Universität Heidelberg. p. 5. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- Holmberg 1998, p. 33

- Danesi 2020, p. 91

- "icon". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- "icono o ícono". Diccionario panhispánico de dudas (in Spanish). Royal Spanish Academy. 2005. Archived from the original on June 4, 2020. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- Babineau, Guy (October 22, 2008). "Why we love Madonna". Xtra Magazine. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- Tomaselli & Scott 2009, pp. 17–18, 61

- Ozlen 2019, p. online

- Wortman, Ana. "Construcción imaginaria de la desigualdad social" (PDF) (in Spanish). Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO). p. 73. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- Menconi, David (June 7, 2015). "Madonna before she was Madonna – dancing at American Dance Festival". The Charlotte Observer. Archived from the original on July 24, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2022.

- O'Brien 2018, p. online

- Hall & Hall 2006, p. 445

- Fresán, Rodrigo (September 3, 2000). "¿Quien es esa mujer?" (in Spanish). Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- Thorpe, Vanessa; Melville-James, Anna (August 8, 1998). "'She wanted the world to know who she was, and it does'". The Independent. Archived from the original on June 20, 2022. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- Rolling Stone Press 1997, p. 16

- Fry, Naomi (March 3, 2016). "'Madonnaland,' by Alina Simone". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 3, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- Russell, Erica (April 24, 2019). "Why Madonna's Legacy of Reinvention is More Relevant Than Ever". MTV. Archived from the original on October 22, 2019. Retrieved July 10, 2022.

- Swan & Utz 2003, p. 14

- Scherstuhl, Alan (March 17, 2012). "So Madonna Is a Satanist, According to This Detailed and Hilarious Christian Post Article". SF Weekly. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- "Madonna, una agente de Satán para unos fanáticos cristianos" (in Spanish). Los 40. October 19, 2014. Retrieved September 24, 2022.

- Pilarczyk, Jamie (September 21, 2010). "Assistant Art Professor Takes Elvis, Madonna to Italy". University of Tampa. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Magid 2013, p. online

- Joppke 2009, p. 132

- EFE (October 21, 2014). Vincent, Peter (ed.). "Singing nun Sister Cristina maintains habit with cover of Madonna's Like a Virgin". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

- Agnew, Paddy (October 24, 2014). "Madonna 'endorses' Singing Nun on release of 'Like a Virgin' cover". The Irish Times. Retrieved September 11, 2022.

Book sources

- Abanes, Richard (2009). Religions of the Stars: What Hollywood Believes and How It Affects You. Baker Books. ISBN 978-1441204455.

- Adogame, Afe; Watson, Nick J.; Parker, Andrew (2017). Global Perspectives on Sports and Christianity. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317573463.

- Ahmed, Akbar S. (2004). Postmodernism and Islam: Predicament and Promise. Psychology Press. ISBN 0415348560.

- Andersen, Robin; Gray, Jonathan Alan (2008). Battleground: The Media. Vol. 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313341670.

- Andersen, Christopher (2015). The Good Son: JFK Jr. and the Mother He Loved. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1476775579.

- Andrews, Marc (2022). Madonna Song by Song. Fonthill Media. ISBN 9781781558447.

- Arjana, Sophia Rose (2020). Buying Buddha, Selling Rumi: Orientalism and the Mystical Marketplace. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1786077721.

- Benstock, Shari; Ferriss, Suzanne (1994). On Fashion. Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0813520339.

- Berger, Arthur Asa (2002). The Art of the Seductress. ISBN 0-595-23077-6.

- Boisvert, Donald L.; Johnson, Jay Emerson (2011). Queer Religion. Vol. 2. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0313353598.

- Belán, Kyra (2018). The Virgin in Art. Parkstone International. ISBN 978-1683255925.

- Bodden, M. C. (2011). Language as the Site of Revolt in Medieval and Early Modern England: Speaking as a Woman. Springer. ISBN 978-0230337657.

- Brand, Benjamin; Rothenberg, David J. (2016). Music and Culture in the Middle Ages and Beyond: Liturgy, Sources, Symbolism. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107158375.

- Breitbart, Andrew; Ebner, Mark (2004). Hollywood, Interrupted: Insanity Chic in Babylon -- The Case Against Celebrity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0471450510.

- Briggs, Asa; Burke, Peter (2009). A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet. Polity. ISBN 978-0745644943.

- Bucar, Liz (2022). Stealing My Religion: Not Just Any Cultural Appropriation. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674287266.

- Buikema, Rosemarie; Liedeke, Plate; van der Tuin, Iris; Thiele, Kathrin (2009). Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-134-00641-0.

- Couldry, Nick; Hepp, Andreas; Krotz, Friedrich (2009). Media Events in a Global Age. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135278540.

- Cross, Mary (2007). Madonna: A Biography. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0313338113.

- Danesi, Marcel (2010). Geeks, Goths, and Gangstas. Canadian Scholars Press. ISBN 978-1551303727.

- Danesi, Marcel (2020). Language, Society, and New Media. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1000048766.

- D'Acierno, Pellegrino; Leonard, George J. (1998). The Italian American Heritage. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 0815303807.

- Detweiler, Craig; Taylor, Barry (2003). A Matrix of Meanings: Finding God in Pop Culture. Baker Academic. ISBN 080102417X.

- Dubin, Steven C. (2013). Arresting Images: Impolitic Art and Uncivil Actions. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135214678.

- Edwards, Katie B. (2015). Rethinking Biblical Literacy. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567521088.

- E. San Juan Jr. (2002). Racism and Cultural Studies: Critiques of Multiculturalist Ideology and the Politics of Difference. Duke University Press. ISBN 0822383705.

- Ferraro, Thomas J. (2005). Feeling Italian: The Art of Ethnicity in America. NYU Press. ISBN 0814728391.

- Fiske, John (2006). Reading the Popular. Routledge. ISBN 1134897855.

- Forbes, Bruce David; Mahan, Jeffrey H. (2005). Religion and Popular Culture in America: Revised Edition. University of California Press. ISBN 0520246896.