Mandrillus

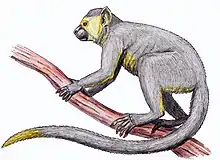

Mandrillus is a genus of large Old World monkeys distributed throughout central and southern Africa, consisting of two species: M. sphinx and M. leucophaeus, the mandrill and drill, respectively.[4] Mandrillus, originally placed under the genus Papio as a type of baboon, is closely related to the genus Cercocebus.[5] They are characterised by their large builds, elongated snouts with furrows on each side, and stub tails. Both species occupy the west central region of Africa and live primarily on the ground.[6][7] They are frugivores, consuming both meat and plants, with a preference for plants.[5] M. sphinx is classified as vulnerable and M. leucophaeus as endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[8][9]

| Mandrillus | |

|---|---|

| |

| A mandrill in captivity | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Cercopithecidae |

| Tribe: | Papionini |

| Genus: | Mandrillus Ritgen, 1824 |

| Type species | |

| Simia sphinx[1][2] | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms[3] | |

| |

Taxonomy

Mandrillus is a genus within the tribe Papionini, which in turn is under the subfamily Cercopithecinae. This subfamily is classified under the family of Old World monkeys (Cercopithecidae) within the infraorder Simiiformes.[4] The Papionini tribe contains six other genera: baboons (Papio), macaques (Macaca), crested mangabeys (Lophocebus), white-eyelid mangabeys (Cercocebus), the highland mangabey (Rungwecebus) and Theropithecus.[10][11]

Originally, both species were considered part of the Papio genus, as forest baboons, due to superficial similarities such as size and appearance, particularly in facial features.[12] However, studies conducted analysing anatomical and genetic differences between the current Mandrillus and Papio genera showed more differences than similarities resulting in the current taxonomic ranking.[13][14] Furthermore, the studies showed Mandrillus are more closely related to the white eyed mangabeys, and diverged relatively recently (4 million years ago) from this genus.[5]

Species

| Common name | Scientific name and subspecies | Range | Size and ecology | IUCN status and estimated population |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drill

|

M. leucophaeus (F. Cuvier, 1807) Two subspecies

|

Western Africa |

Size: 61–77 cm (24–30 in) long, plus 5–8 cm (2–3 in) tail[15] Habitat: Forest, savanna, and rocky areas[9] Diet: Omnivorous, primarily fruit and seeds[9] |

EN

|

| Mandrill

|

M. sphinx (Linnaeus, 1758) |

Western Africa |

Size: 55–95 cm (22–37 in) long, plus 7–10 cm (3–4 in) tail[16] Habitat: Forest[8] Diet: Fruit, seeds, fungi, roots, insects, snails, worms, frogs, and lizards, as well as snakes and small vertebrates[17] |

VU

|

Anatomy

Both species of Mandrillus develop extremely large muzzles, prominent nasal ridges and paranasal swelling (swelling in the area adjacent to the nostrils). The size and colour of the paranasal swellings correlate to male dominance and rank, while the size of nasal ridges is a way of attracting mates.[18] Mandrillus teeth consist of two incisors, two premolars, one canine and three molars in each half of the upper and lower jaw, totalling 32 teeth.[5] Furthermore Mandrillus display larger premolars and extended canines; these dental traits are better adapted to crushing hard objects. This is due to a large part of their diet consisting of hard, dry nuts and seeds that require greater crushing power and the use of their teeth in ripping apart rotting wood to search for insects and other invertebrates.[19]

Within the shoulder and upper arm structures of the Mandrillus monkeys a deep scapular, broad deltoid plane, narrow stable elbow region and other skeletal features indicate the use of the forelimbs for climbing and foraging.[20] This is used by the monkeys to climb trees when searching for ripe fruit and in the aggressive foraging of the forest floor in search of food.[19] Mandrillus monkeys have developed an extremely broad and robust ilium, and a rounded tibial shaft. The development of these features can be attributed to the climbing of trees and quadrupedal locomotion. The largest toe is separated from the remaining toes for increased grasping power when climbing trees.[5]

Sexual dimorphism

Both species of Mandrillus demonstrate a great degree of sexual dimorphism in weight, anatomy and physical appearance. The mandrill displays the most extreme sexual dimorphism for weight among all primates, with a male-female weight ratio of 3.2 – 3.4 at eight to ten years of age.[21] Similarly, drills are one of the most sexually dimorphic primates for body weight, with a male growing up to 32 kg while a female grows to 12 kg. Sexual dimorphism is also displayed in the growth of the craniofacial bones of both species.[22] The males of each species have longer muzzles, much larger paranasal swellings and longer canines than their female counterparts. In a study of wild drills, female muzzles only grew up to 70% the length of the male muzzles.[5][22] Furthermore, males have brightly coloured, saturated rumps unlike their female counterparts.[5] Both species also display the greatest visual sexual dimorphism within monkeys. On a scale based on rating the differences in physical features between genders, the mandrill obtained 32 whilst the drill obtained 24.5.[5] These ratings are based on features such as the saturation and colour of the rump (and face for mandrills), the paranasal swelling, the fatted rump and fur colouring.[5]

Distribution and habitat

Mandrillus monkeys have a very localised biographical region located in West central Africa. The two species are often considered allopatric,[18][5] they occupy non-overlapping regions, and their regions are divided by a physical barrier, the Sanaga river in Cameroon. Mandrillus leucophaeus occupy the area above the river in North western Cameroon and southwestern Nigeria up until the Cross River, and Bioko Island (Equatorial Guinea) which lies off the coast.[18][5] The mandrill occupies the area below the river line in Cameroon, Río Muni, Gabon and Congo.[18] The Mandrillus species occupy multiple sections of the Guinean forests of West Africa, including Cross–Sanaga–Bioko coastal forests and Cameroonian Highlands forests.[23][18] The forests the monkeys occupy have a humid, tropical climate and rugged terrain. Deforestation has reduced the habitat of both Mandrillus species, reducing the distribution of each species, especially the drill.[5]

Behaviour

Diet

Both Mandrillus species are frugivores, consuming both plants and insects with a preference for fruits and nuts. Mandrillus species spend a large amount of their time foraging through the forest in search of food.[24] In a study conducted in Cameroon, approximately 84% of the faecal matter of mandrills consisted of fruit.[5] Similarly, a study done on drills in southwest Cameroon showed that the mean weight of fruit and seed in faecal matter was equal to or greater than 80%.[25] Seasonal changes can be seen within Mandrillus diet, during peak fruit season (September to March) their diet consisted mostly of fruit, pulp and seeds whilst during the fruit scarce season (June to August) there was a great increase in the consumption of insects, woody tissue and especially nuts.[26][5] There was also an increase in the variation of the diet during the fruit-scarce season.[26][27] Important fruit include but are not limited to, the fruit of the bush mango (Irvingia gabonensis), African Corkwood tree (Musanga cecropioides), Grewia coriacea, Sacoglottis gabonensis and Xylopia aethiopica. Invertebrates consumed include crickets, ants, caterpillars and termites. Rarely, Mandrillus monkeys will eat larger animals, such as rats and gazelles when presented with the opportunity.[24][5][27]

Social systems

The species of the genus exhibit great similarities in their social systems. Both generally form smaller groups, however the size of these groups is unclear. A study done on drills in southwest Cameroon found a mean group size of 52.3[27] while another more recent report stated a figure of 25–40 on these smaller groups.[28] A study of mandrills done at Campo reserve in Cameroon found small groups contain 14 - 95 individuals.[5] These smaller groups, with stable social structures, often join to form larger "supergroups" of hundreds of individuals.[28] Some of the largest mandrill "supergroups" reported contained up to 845 individuals whilst some of the largest drill "supergroups" reported contained 400 individuals.[24][5] There has been reports of solitary male Mandrillus monkeys, however this occurs very rarely.[5]

The social structures and social hierarchy of Mandrillus "supergroups" and groups is highly contentious. There are multiple older (1970s-1990s) sources referencing single male units, which contained a male and multiple female monkeys, as the smallest and most common stable social structure. However this has been disproved with the discovery of less colourful male Mandrillus and further observations of behaviour.[5][29][27][30] Mandrillus leucophaeus social structures are unknown, due to low populations, and secluded habitats with dense forestry.[28] On the other hand, Mandrillus sphinx has had a variety of studies on social structure done in largely captive and semi-free ranging settings, with few studies on wild mandrills. The current studies on mandrills are inconclusive, and present different results. Various semi-free ranging studies conducted report a matrilineal social structure with a stable infant and female mandrill "supergroup". Male Mandrillus monkeys would disperse from this group when old enough and join other groups only during mating season.[29][5] Further studies, also done in semi-free ranging settings, conclude that dominant females are central to group cohesion and connectivity (how close they remained).[5][29] Conversely, a study on wild mandrills published in 2015 reported that a stable adult, male mandrill population of 5 - 6 was present year round in "supergroups".[31] This aligned with the social structures reported in other research papers done on wild mandrills, where stable multi-male and multi-female groups were found.[32][31][27] This difference in social structures between Mandrillus groups has been attributed to limitations in observing wild mandrills, differing habitats, and differing sample sizes.[29]

Male dominance and rank have been linked to the colouration and colour extension of the rumps, greater saturation and colour extension correlated to higher-ranking males. Males of higher ranking are more likely to associate with females, especially those with sexual skin swelling, and more likely to successfully mount females.[28][5] Dominant, adult males practice mate guarding on adult females during times of maximal skin swelling; with their high competitive ability they are more likely to successfully reproduce.[28] Due to the tropical habitat, mating season coincides with the dry season (May to October) and birth season coincides with the wet season (November to April).[5]

Communication

.jpg.webp)

The Mandrillus genus uses both visual and vocal forms of communication, which are extremely similar or identical across both species. Both species have three identical long-range vocal communications: two-phase grunts, roars and "crowling".[5] The two-phased grunt is a low, two-syllable continuous sound used exclusively by adult males during calm group progression and mate guarding.[33] Roars are single low, single syllable sounds used exclusively by males in the same context as two-phase grunts. Crowling is used by infants and females during group movement or foraging to call together the dispersed group.[33][5][34]

They also use numerous short-range vocal sounds for various purposes. The "yak" and grinding of teeth are used during tense situations. The grunt is used in aggressive situations and screams are used to escape or while experiencing fear. The growl is used to convey mild alarm, the K-alarm is used to convey intense alarm and the "girney" is used for appeasement.[33] Both species use various facial expressions to communicate with each other. The silent baring of teeth is a positive visual signal conveying peaceful intentions, and it is often combined with a shaking head.[35] Staring open-mouthed is a display of aggression, frowning with bare teeth is used to encourage submission, staring with bare teeth can communicate aggression or fear, pouting signals submission and a relaxed open mouth encourages playing.[5]

Conservation status

The current conservation status of Mandrillus sphinx is vulnerable and that for Mandrillus leucophaeus is endangered.[9][8] The greatest threats to the conservation of this genus are the severe loss and degradation of their habitat, and hunting.[36][37] The loss of habitat is an ongoing threat that can be attributed to the expansion of human settlements as well as the clearing of forests for chipping factories and agriculture. Hunting and poaching of Mandrillus monkeys for meat or to protect crops is also major, ongoing threat to the population despite the implementation of hunting restrictions and sanctuaries.[8][9] The drill population in Cameroon, which encompasses 80% of the drill's original habitat, has been fragmented into smaller, isolated populations with largest residing in Korup national park.[36] The mandrill population in south Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea are at great risk due to extensive forest loss. The majority of the mandrill population remains in Gabon and faces major threats from railroad construction and logging companies.[5] As of 2020, the mandrill population is in decline while the drill population is not able to be accurately determined.[8][9]

References

- Allen, Glover M. (1939). "A Checklist of African Mammals". Bulletin of the Museum of Comparative Zoölogy at Harvard College. 83: 157.

- Melville, R. V. (1982). "Opinion 1199. Papio Erxleben, 1777, and Mandrillus Ritgen, 1824 (Mammalia, Primates): Designation of Type Species". The Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature. 39 (1): 15–18.

- Groves, C. P. (2005). "Mandrillus". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 165. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- "ITIS Standard Report Page: Mandrillus". www.itis.gov. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Dixson, Alan F. The Mandrill : a Case of Extreme Sexual Selection. Cambridge. ISBN 978-1-316-33534-5. OCLC 941030864.

- "Drill | primate". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- "Mandrill | primate". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-18.

- Abernethy, K.; Maisels, F. (2019). "Mandrillus sphinx". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T12754A17952325. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T12754A17952325.en.

- Gadsby, E. L.; Cronin, D. T.; Astaras, C.; Imong, I. (2020). "Mandrillus leucophaeus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T12753A17952490. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T12753A17952490.en.

- "ASM Mammal Diversity Database". American Society of Mammalogists. Retrieved 2020-05-26.

- Seamons, G.R. (July 2006). "Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd edition)". Reference Reviews. 20 (5): 41–42. doi:10.1108/09504120610673024. ISSN 0950-4125.

- Strasser, Elizabeth; Delson, Eric (1987-01-01). "Cladistic analysis of cercopithecid relationships". Journal of Human Evolution. 16 (1): 81–99. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(87)90061-3. ISSN 0047-2484.

- Science, American Association for the Advancement of (1999-02-12). "When Is a Mandrill Not a Baboon?". Science. 283 (5404): 931. doi:10.1126/science.283.5404.931a. ISSN 0036-8075. S2CID 81792789.

- Disotell, Todd R. (1994). "Generic level relationships of the Papionini (Cercopithecoidea)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 94 (1): 47–57. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330940105. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 8042705.

- Briercheck, Ken (2023). "Mandrillus leucophaeus". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on July 18, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- Kingdon 2015, p. 129

- Ingmarsson, Lisa (2023). "Mandrillus sphinx". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan. Archived from the original on May 15, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- Lehman, S., & Fleagle, J. (2006). Primate Biogeography Progress and Prospects . Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Fleagle, John G.; McGraw, W. Scott (2002-03-01). "Skeletal and dental morphology of African papionins: unmasking a cryptic clade". Journal of Human Evolution. 42 (3): 267–292. doi:10.1006/jhev.2001.0526. ISSN 0047-2484. PMID 11846531.

- Fleagle, John G.; McGraw, W. Scott (1999-02-02). "Skeletal and dental morphology supports diphyletic origin of baboons and mandrills". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 96 (3): 1157–1161. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.3.1157. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 15367. PMID 9927710.

- Setchell, Joanna M.; Lee, Phyllis C.; Wickings, E. Jean; Dixson, Alan F. (2001). "Growth and ontogeny of sexual size dimorphism in the mandrill (Mandrillus sphinx)". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 115 (4): 349–360. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1091. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 11471133.

- Elton, Sarah; Morgan, Bethan J. (2006-04-01). "Muzzle size, paranasal swelling size and body mass in Mandrillus leucophaeus" (PDF). Primates. 47 (2): 151–157. doi:10.1007/s10329-005-0164-6. ISSN 1610-7365. PMID 16317498. S2CID 13602724.

- "Western Africa: Coastal parts of Cameroon, Equator | Ecoregions | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- Nsi Akoue, Gontran; Mbading-Mbading, Wilfried; Willaume, Eric; Souza, Alain; Mbatchi, Bertrand; Charpentier, Marie J. E. (September 2017). Tregenza, T. (ed.). "Seasonal and individual predictors of diet in a free-ranging population of mandrills". Ethology. 123 (9): 600–613. doi:10.1111/eth.12633.

- Astaras, C.; Waltert, M. (December 2010). "What does seed handling by the drill tell us about the ecological services of terrestrial cercopithecines in African forests?: Terrestrial forest primates' role in forest dynamics". Animal Conservation. 13 (6): 568–578. doi:10.1111/j.1469-1795.2010.00378.x. S2CID 82430448.

- Hongo, Shun; Nakashima, Yoshihiro; Akomo-Okoue, Etienne François; Mindonga-Nguelet, Fred Loïque (February 2018). "Seasonal change in diet and habitat use in wild mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx)". International Journal of Primatology. 39 (1): 27–48. doi:10.1007/s10764-017-0007-5. hdl:2433/230380. ISSN 0164-0291. S2CID 32935826.

- Astaras, Christos; Mühlenberg, Michael; Waltert, Matthias (March 2008). "Note on drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus) ecology and conservation status in Korup National Park, Southwest Cameroon". American Journal of Primatology. 70 (3): 306–310. doi:10.1002/ajp.20489. PMID 17922527. S2CID 21284777.

- Marty, Jill S.; Higham, James P.; Gadsby, Elizabeth L.; Ross, Caroline (December 2009). "Dominance, coloration, and social and sexual behavior in male drills Mandrillus leucophaeus". International Journal of Primatology. 30 (6): 807–823. doi:10.1007/s10764-009-9382-x. ISSN 0164-0291. S2CID 38938846.

- Bret, Céline; Sueur, Cédric; Ngoubangoye, Barthélémy; Verrier, Delphine; Deneubourg, Jean-Louis; Petit, Odile (2013-12-10). Engelhardt, Antje (ed.). "Social structure of a semi-free ranging group of mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx): a social network analysis". PLOS ONE. 8 (12): e83015. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0083015. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3858359. PMID 24340074.

- Hongo, Shun (2014-10-01). "New evidence from observations of progressions of mandrills (Mandrillus sphinx): a multilevel or non-nested society?". Primates. 55 (4): 473–481. doi:10.1007/s10329-014-0438-y. hdl:2433/200186. ISSN 1610-7365. PMID 25091875. S2CID 15104161.

- Brockmeyer, Timo; Kappeler, Peter M.; Willaume, Eric; Benoit, Laure; Mboumba, Sylvère; Charpentier, Marie J.E. (October 2015). "Social organization and space use of a wild mandrill ( Mandrillus sphinx ) group: Mandrill Social Organization and Space Use". American Journal of Primatology. 77 (10): 1036–1048. doi:10.1002/ajp.22439. PMID 26235675. S2CID 38327403.

- Harrison, Michael J. S. (October 1988). "The mandrill in Gabon's rain forest—ecology, distribution and status". Oryx. 22 (4): 218–228. doi:10.1017/S0030605300022365. ISSN 0030-6053.

- Kudo, Hiroko (July 1987). "The study of vocal communication of wild mandrills in Cameroon in relation to their social structure". Primates. 28 (3): 289–308. doi:10.1007/bf02381013. ISSN 0032-8332. S2CID 1507136.

- Astaras, Christos. (2009). Ecology and status of the drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus) in Korup National Park, Southwest Cameroon : implications for conservation (1. ed.). Göttingen: Optimus Mostafa. ISBN 978-3-941274-19-8. OCLC 434519864.

- Bout, N.; Thierry, B. (December 2005). "Peaceful Meaning for the Silent Bared-Teeth Displays of Mandrills". International Journal of Primatology. 26 (6): 1215–1228. doi:10.1007/s10764-005-8850-1. ISSN 0164-0291. S2CID 31905432.

- Morgan, Bethan J.; Abwe, Ekwoge E.; Dixson, Alan F.; Astaras, Christos (2013-04-01). "The Distribution, Status, and Conservation Outlook of the Drill (Mandrillus leucophaeus) in Cameroon". International Journal of Primatology. 34 (2): 281–302. doi:10.1007/s10764-013-9661-4. ISSN 1573-8604. S2CID 14417124.

- Olney, P. J. S. (1994). Creative Conservation : Interactive management of wild and captive animals. Mace, G. M., Feistner, A. T. C. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. ISBN 978-94-011-0721-1. OCLC 840308626.

Sources

- Kingdon, Jonathan (2015). The Kingdon Field Guide to African Mammals (Second ed.). Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4729-2531-2.

.jpg.webp)