Mapusaurus

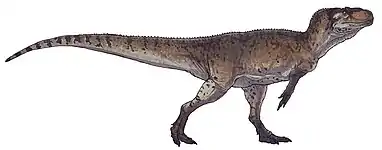

Mapusaurus (lit. 'Earth lizard') was a giant carcharodontosaurid carnosaurian dinosaur from the early Late Cretaceous (early Turonian stage), approximately 93.9 to 89.6 million years ago, of what is now Argentina.

| Mapusaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous (early Turonian), ~ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skeletons of an adult and a juvenile (left) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Carcharodontosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Carcharodontosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Giganotosaurini |

| Genus: | †Mapusaurus Coria & Currie, 2006 |

| Type species | |

| †Mapusaurus roseae Coria & Currie, 2006 | |

Discovery

Mapusaurus was excavated between 1997 and 2001, by the Argentinian-Canadian Dinosaur Project, from an exposure of the Huincul Formation (Rio Limay Subgroup, Cenomanian) at Cañadón del Gato. It was described and named by paleontologists Rodolfo Coria and Phil Currie in 2006.[1]

The name Mapusaurus is derived from the Mapuche word Mapu, meaning 'of the Land' or 'of the Earth' and the Greek sauros, meaning 'lizard'. The type species, Mapusaurus roseae, is named for both the rose-colored rocks, in which the fossils were found and for Rose Letwin, who sponsored the expeditions which recovered these fossils.

The designated holotype for the genus and type species, Mapusaurus roseae, is an isolated right nasal (MCF-PVPH-108.1, Museo Carmen Funes, Paleontología de Vertebrados, Plaza Huincul, Neuquén). Twelve paratypes have been designated, based on additional isolated skeletal elements. Taken together, the many individual elements recovered from the Mapusaurus bone bed represent most of the skeleton.[1]

Description

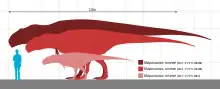

Mapusaurus was a large theropod, but slightly smaller in size than its close relative Giganotosaurus, measuring up to 11–12.2 m (36–40 ft) long and weighing over 5 metric tons (5.5 short tons) at maximum.[1][2][3]

It has been determined that Mapusaurus was diagnosed on autapomorphies, or unique traits, in regions of the skeleton that Giganotosaurus does not preserve. Mapusaurus only differs from Giganotosaurus in lacking a second opening on the middle quadrate, and in some details of the topology of the nasal rugosities.[4]

Paleobiology

The fossil remains of Mapusaurus were discovered in a bone bed containing at least seven to possibly up to nine individuals of various growth stages.[1][5][6] Coria and Currie speculated that this may represent a long term, possibly coincidental accumulation of carcasses (some sort of predator trap) and may provide clues about Mapusaurus behavior.[1] Other known theropod bone beds and fossil graveyards include those of Deinonychus and other dromaeosaurids around the planet, the Allosaurus-dominated Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry of Utah, an Albertosaurus bone bed from Alberta, a Daspletosaurus bone bed from Montana, a potential Teratophoneus bone bed from Utah, and even a Tyrannosaurus bone bed from Montana, as well.

Paleontologist Rodolfo Coria, of the Museo Carmen Funes, contrary to his published article, repeated in a press-conference earlier suggestions that this congregation of fossil bones may indicate that Mapusaurus like Giganotosaurus also hunted in groups and worked together to take down large prey, such as the immense sauropod Argentinosaurus.[7] If so, this would be the first substantive evidence of gregarious behavior by large theropods other than Tyrannosaurus, although whether they might have hunted in organized packs (as wolves and lions do) or simply attacked in a mob, is unknown. The authors interpreted the depositional environment of the Huincul Formation at the Cañadón del Gato locality as a freshwater paleochannel deposit, "laid down by an ephemeral or seasonal stream in a region with arid or semi-arid climate".[1] This bone bed is especially interesting, in light of the overall scarcity of fossilized bone within the Huincul Formation. An ontogenetic study by Canale et al. (2014)[6] found that Mapusaurus displayed heterochrony, an evolutionary condition in which the animals may retain an ancestral characteristic during one stage of their life, but lose it as they develop. In Mapusaurus, the maxillary fenestrae are present in younger individuals, but gradually disappear as they mature.

Classification

Cladistic analysis carried out by Coria and Currie definitively showed that Mapusaurus is nested within the clade Carcharodontosauridae. The authors noted that the structure of the femur suggests a closer relationship with Giganotosaurus than either taxon shares with Carcharodontosaurus. They created a new monophyletic taxon based on this relationship, the subfamily Giganotosaurinae, defined as all carcharodontosaurids closer to Giganotosaurus and Mapusaurus than to Carcharodontosaurus. They tentatively included the genus Tyrannotitan in this new subfamily, pending publication of more detailed descriptions of the known specimens of that form.[1]

The following cladogram after Novas et al., 2013, shows the placement of Mapusaurus within Carcharodontosauridae.[8]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In 2022, a new carcharodontosaurid called Meraxes was described, prompting a second organization scheme. Canale et al. recovered Meraxes as the earliest diverging member of the tribe Giganotosaurini. This is the updated cladogram.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

As previously mentioned, the Huincul Formation is thought to represent an arid environment with ephemeral or seasonal streams. The age of this formation is estimated at 97 to 93.5 MYA.[9] The dinosaur record is considered sparse here. Mapusaurus shared its environment with the sauropods Argentinosaurus (one of the largest sauropods, if not the largest), Choconsaurus, Chucarosaurus and Cathartesaura. Another carcharodontosaurid known as Meraxes was found in the same formation, but in older rocks than Mapusaurus, so they likely were not coevals.[10] The abelisaurid theropods Skorpiovenator and Ilokelesia also lived in the region.[11]

Fossilized pollen indicates a wide variety of plants was present in the Huincul Formation. A study of the El Zampal section of the formation found hornworts, liverworts, ferns, Selaginellales, possible Noeggerathiales, gymnosperms (including gnetophytes and conifers), and angiosperms (flowering plants), in addition to several pollen grains of unknown affinities.[12] The Huincul Formation is among the richest Patagonian vertebrate associations, preserving fish including dipnoans and gar, chelid turtles, squamates, sphenodonts, neosuchian crocodilians, and a wide variety of dinosaurs.[13][14] Vertebrates are most commonly found in the lower, and therefore older, part of the formation.[15]

References

- Coria, R. A.; Currie, P. J. (2006). "A new carcharodontosaurid (Dinosauria, Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous of Argentina" (PDF). Geodiversitas. 28 (1): 71–118. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.624.2450. ISSN 1280-9659.

- Paul, Gregory S (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. p. 98.

- Holtz, Thomas R. (2021). "Theropod guild structure and the tyrannosaurid niche assimilation hypothesis: implications for predatory dinosaur macroecology and ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 58 (9): 778−795. doi:10.1139/cjes-2020-0174. hdl:1903/28566.

- Carrano, Matthew T.; Benson, Roger B. J.; Sampson, Scott D. (June 1, 2012). "The phylogeny of Tetanurae (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 10 (2): 211–300. Bibcode:2012JSPal..10..211C. doi:10.1080/14772019.2011.630927. ISSN 1477-2019. S2CID 85354215.

- Eddy, Drew R.; Clarke, Julia A. (March 21, 2011). "New Information on the Cranial Anatomy of Acrocanthosaurus atokensis and Its Implications for the Phylogeny of Allosauroidea (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". PLOS ONE. 6 (3): e17932. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...617932E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0017932. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3061882. PMID 21445312.

- Canale, Juan Ignacio; Novas, Fernando Emilio; Salgado, Leonardo; Coria, Rodolfo Aníbal (December 1, 2015). "Cranial ontogenetic variation in Mapusaurus roseae (Dinosauria: Theropoda) and the probable role of heterochrony in carcharodontosaurid evolution". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 89 (4): 983–993. doi:10.1007/s12542-014-0251-3. ISSN 0031-0220. S2CID 133485236.

- "Details Revealed About Huge Dinosaurs". ABC News US. Associated Press. 2006.

- Novas, Fernando E. (2013). "Evolution of the carnivorous dinosaurs during the Cretaceous: The evidence from Patagonia". Cretaceous Research. 45: 174–215. Bibcode:2013CrRes..45..174N. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2013.04.001.

- Huincul Formation at Fossilworks.org

- Canale, J.I.; Apesteguía, S.; Gallina, P.A.; Mitchell, J.; Smith, N.D.; Cullen, T.M.; Shinya, A.; Haluza, A.; Gianechini, F.A.; Makovicky, P.J. (July 7, 2022). "New giant carnivorous dinosaur reveals convergent evolutionary trends in theropod arm reduction". Current Biology. 32 (14): 3195–3202.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2022.05.057. PMID 35803271.

- Sánchez, Maria Lidia; Heredia, Susana; Calvo, Jorge O. (2006). "Paleoambientes sedimentarios del Cretácico Superior de la Formación Plottier (Grupo Neuquén), Departamento Confluencia, Neuquén" [Sedimentary paleoenvironments in the Upper Cretaceous Plottier Formation (Neuquen Group), Confluencia, Neuquén]. Revista de la Asociación Geológica Argentina. 61 (1): 3–18 – via ResearchGate.

- Vallati, P. (2001). "Middle cretaceous microflora from the Huincul Formation ("Dinosaurian Beds") in the Neuquén Basin, Patagonia, Argentina". Palynology. 25 (1): 179–197. Bibcode:2001Paly...25..179V. doi:10.2113/0250179.

- Motta, M.J.; Aranciaga Rolando, A.M.; Rozadilla, S.; Agnolín, F.E.; Chimento, N.R.; Egli, F.B.; Novas, F.E. (2016). "New theropod fauna from the upper cretaceous (Huincul Formation) of Northwestern Patagonia, Argentina". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 71: 231–253.

- Motta, M.J.; Brissón Egli, F.; Aranciaga Rolando, A.M.; Rozadilla, S.; Gentil, A. R.; Lio, G.; Cerroni, M.; Garcia Marsà, J.; Agnolín, F. L.; D'Angelo, J. S.; Álvarez-Herrera, G. P.; Alsina, C.H.; Novas, F.E. (2019). "New vertebrate remains from the Huincul Formation (Cenomanian–Turonian;Upper Cretaceous) in Río Negro, Argentina". Publicación Electrónica de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina. 19 (1): R26. doi:10.5710/PEAPA.15.04.2019.295. hdl:11336/161858. S2CID 127726069. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 14, 2019.

- Bellardini, F.; Filippi, L.S. (2018). "New evidence of saurischian dinosaurs from the upper member of the Huincul Formation (Cenomanian) of Neuquén Province, Patagonia, Argentina". Reunión de Comunicaciones de la Asociación Paleontológica Argentina: 10.

External links

- Meat-Eating Dinosaur Was Bigger Than T. Rex. National Geographic News

- "What were the longest/heaviest predatory dinosaurs?". Mike Taylor. The Dinosaur FAQ. August 27, 2002. (Named as Unnamed Argentinian Carcharodontosaurine)

- "[And the Largest Theropod is... http://dml.cmnh.org/2003Jul/msg00355.html]". The Dinosaur Mailing List Archives. Retrieved March 21, 2010 (Named as Undescribed Carcharodontosaurine)

.jpg.webp)