MRT Line 3 (Metro Manila)

The Metro Rail Transit Line 3, also known as the MRT Line 3, MRT-3 or Metrostar Express, is a light rapid transit system line of Metro Manila, Philippines. Originally referred to as the Blue Line, MRT Line 3 was reclassified to be the Yellow Line in 2012. The line runs in an orbital north to south route following the alignment of Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA). Although it has some characteristics of light rail, such as the type of a tram-like rolling stock used, it is more akin to a rapid transit system owing to its total grade separation and high passenger throughput.[7]

| MRT Line 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

An MRTC 3000 class train at North Avenue station in July 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Native name | Filipino: Ikatlong Linya ng Sistema ng Kalakhang Riles Panlulan ng Maynila | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Status | Operational | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Metro Rail Transit Corporation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line number | 3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Metro Manila, Philippines | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Termini | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stations | 13[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Website | DOTr-MRT3 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Light rapid transit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| System | Manila Metro Rail Transit System | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Services | 1[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator(s) | Department of Transportation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Depot(s) | North Avenue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | MRTC 3000 class[1] MRTC 3100 class[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Daily ridership | 273,141 (2022)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 98,330,683 (2022)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | December 15, 1999 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Completed | July 20, 2000 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line length | 16.9 km (10.5 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Number of tracks | Double-track | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Character | Grade separated | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Loading gauge | 3,730 mm × 2,600 mm (12 ft 3 in × 8 ft 6 in)[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Minimum radius | Mainline: 370 m (1,210 ft) Depot: 25 m (82 ft) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrification | 750 V DC overhead lines | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 60 km/h (37 mph) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signalling | Alstom CITYFLO 250 fixed block[4][5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum incline | Mainline: 4% Depot spur line: 5%[6] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Average inter-station distance | 1.28 km (0.80 mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Envisioned in the 1970s and 1980s as part of various feasibility studies, the thirteen-station, 16.9-kilometer (10.5 mi) line was the second rapid transit line to be built in Metro Manila when it started full operations in 2000 under a 25-year concession agreement between its private owners and the Philippine government's Department of Transportation (DOTr).

The line is owned by the Metro Rail Transit Corporation (MRTC), a private company operating in partnership with the DOTr under a Build-Lease-Transfer agreement. Serving close to 550,000 passengers on a daily basis when MRTC's maintenance provider, Sumitomo Corporation of Japan, was handling the maintenance of the system, the line is the busiest among Metro Manila's three rapid transit lines, built with essential standards such as barrier-free access and the use of contact-less card tickets to better facilitate passenger access. Total ridership significantly exceeds its built maximum capacity of 350,000 passengers a day, with various solutions being proposed or implemented to alleviate chronic congestion in addition to the procurement of new rolling stock.

Since 2006, the system's private owners had been offering various capacity expansion proposals to the DOTC. In 2014, after the DOTC's handling of the line's maintenance for two years amid questions about the line's structural integrity owing to the poor maintenance and the pronouncements that the system, in general, was safe, experts from MTR HK were commissioned to review the system. MTR HK made the opinion that the rail system was compromised due to the DOTC's poor maintenance.[8][9][10] In response to this, the line underwent a comprehensive rehabilitation program funded by Japan's official development assistance from 2019 to 2021. This resulted in upgraded facilities, railway tracks, trains, and other systems.[11][12][13]

It is integrated with the public transit system in Metro Manila, and passengers also take various forms of road-based public transport, such as buses, to and from a station to reach their intended destination. Although the line is aimed at reducing traffic congestion and travel time along EDSA, the transportation system has only been partially successful due to the DOTC's inaction on the private sector's proposals to expand the capacity of the system to take up to 1.1 million passengers a day. Expanding the network's capacity to accommodate the rising number of passengers is currently set on tackling this problem.

Route

The lines run along the alignment of Epifanio de los Santos Avenue from North Avenue in Quezon City to the intersection of EDSA and Taft Avenue in Pasay. The rails are mostly elevated and erected either over or along the roads covered, with cut and underground sections between Buendia and Ayala stations, the only underground stations on the line. The rail line serves the cities that Circumferential Road 4 (Epifanio de los Santos Avenue) passes through: Pasay, Makati, Mandaluyong, San Juan and Quezon City. The line crosses South Luzon Expressway (SLEX) at Magallanes Interchange in Makati.

Early on during the construction of the line, a plan was drafted for a spur line which run from Buendia to Gil Puyat stations, built between Ayala and Buendia stations. The remaining evidence of this abandoned plan is an underground tunnel between Buendia and Ayala stations turning right, heading towards Ayala Avenue. The planned spur line was cancelled due to the Asian financial crisis in 1997, which resulted the spur line area to be abandoned since the line's opening in 1999. Although occasionally mentioned, there are currently no plans to revisit this abandoned plan.

Stations

The line has 13 stations along its 16.9-kilometer (10.5 mi) route,[1] spaced on average around 1.3 kilometers (0.81 mi) apart.[1] The southern terminus of the line is Taft Avenue at Pasay Rotonda, the intersection between Epifanio de los Santos Avenue and Taft Avenue, while the northern terminus is the North Avenue along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue in Barangay Bagong Pag-asa, Quezon City. Three stations serve as connecting stations with the lines operated by the Light Rail Manila Corporation (LRMC), Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA), and Philippine National Railways (PNR). The Magallanes station is near PNR's EDSA station, while Araneta Center–Cubao is indirectly connected to the LRT Line 2 station of the same, and Taft Avenue is connected via a covered walkway to the LRT Line 1 EDSA station. No stations are connected to other rapid transit lines within the paid areas, though that is set to change when the North Triangle Common Station, which has interchanges to LRT Line 1 and MRT Line 7, opens in 2023.

There are plans to temporarily close North Avenue to facilitate the construction of the North Triangle Common Station. This is to minimize the operational and safety risks to the overhead catenary wires above the turn back siding north of the North Avenue station. Should this closure proposal be approved, Quezon Avenue will be the temporary terminus of the line. The closure will take place for 30 days.[14]

| Name | Distance (km) | Connections | Location | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between stations |

Total | ||||

| North Triangle | — | — | Interchange with Interchange with

|

Quezon City | |

| North Avenue | — | 0.000 |

| ||

| Quezon Avenue | 1.200 | 1.200 |

| ||

| Kamuning | 1.000 | 2.200 |

| ||

| Araneta Center–Cubao | 1.900 | 4.100 |

| ||

| Santolan | 1.500 | 5.600 |

| ||

| Ortigas | 2.300 | 7.900 |

|

Mandaluyong | |

| Shaw Boulevard | 0.800 | 8.700 | none | ||

| Boni | 1.000 | 9.700 | none | ||

| Guadalupe | 0.800 | 10.500 |

|

Makati | |

| Buendia | 2.000 | 12.500 |

| ||

| Ayala | 0.950 | 13.450 |

| ||

| Magallanes | 1.200 | 14.650 | |||

| Taft Avenue | 2.050 | 16.700 |

|

Pasay | |

| Stations, lines, and/or other transport connections in italics are either under construction, proposed, unopened, or have been closed. | |||||

Operations

The line is open from 4:40 a.m. PHT (UTC+8) until 10:10 p.m. on a daily basis.[15] It operates almost every day of the year unless otherwise announced. Special schedules are announced via the public address system in every station and also in newspapers and other mass media. During Holy Week, a public holiday in the Philippines, the line is closed for annual maintenance, owing to fewer commuters and traffic around the metro, leaving the EDSA Carousel as an alternative mode of transport.[16] Normal operation resumes after Easter Sunday.[17] During the Christmas and year-end holidays, the operating hours of the line are shortened due to the low ridership of the line during the holidays.[18]

It has experimented with extended opening hours, the first of which included 24-hour operations beginning on June 1, 2009 (primarily aimed at serving call center agents and other workers in the business process outsourcing sector).[19] Citing low ridership figures and financial losses, this was suspended after two days, and operations were instead extended from 5:00 a.m. to 1:00 am.[20] Operations subsequently returned to the former schedule (5:30 a.m. until 11:00 p.m. on weekdays, and 5:30 a.m. until 10:00 pm during weekends and holidays) by April 2010, but services were again extended starting March 10, 2014, with trains running on a trial basis from 4:30 am to 11:30 pm in anticipation of major traffic buildup in light of several major road projects beginning in 2014.[21]

History

Early planning

In 1973, the Overseas Technical Cooperation Agency (OTCA; predecessor of the Japan International Cooperation Agency) presented a plan to construct five subway lines in Metro Manila. The study was known as the Urban Transport Study in the Manila Metropolitan Area. One of the five lines, Line 3, was planned as a 24.3-kilometer (15.1 mi) line along Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA), the region's busiest road corridor. The plan would have resolved the traffic problems of Metro Manila and would have taken 15 years to complete.[22]

Another study by JICA was presented in 1976 which included the five lines proposed in 1973. The study recommended heavy rail due to the rising population.[22]

During the construction of the first line of the Manila Light Rail Transit System in the early 1980s, Electrowatt Engineering Services of Zürich designed a comprehensive plan for metro service in Metro Manila. The plan—still used as the basis for planning new metro lines—consisted of a 150-kilometer (93 mi) network of rapid transit lines spanning all major corridors within 20 years.[23] The study integrated the previous 1973 OTCA study, the 1976 JICA study, and the 1977 Freeman Fox and Associates study, which was used as the basis for the LRT Line 1.[22]

Development and early delays

The project was restarted as a light rail project in 1989, originally known as the LRT-3 project. It was to be bid out as a build-operate-transfer project, with the Hong Kong-based EDSA LRT Corporation winning the public bidding for the line's construction in 1991 during the term of President Corazon Aquino.[24] However, construction could not commence, with the project stalled as the Philippine government conducted several investigations into alleged irregularities with the project's contract.[25] In 1995, the Supreme Court upheld the regularity of the project which paved the way for construction to finally begin during the term of President Fidel V. Ramos.[26] A consortium of local companies, led by Fil-Estate Management was later joined by Ayala Land, and 5 others, later formed the Metro Rail Transit Corporation (MRTC) in June 1995 and took over the EDSA LRT Corporation.[24]

Construction and opening

The MRTC was subsequently awarded a Build-Lease-Transfer contract by the DOTC, which meant that the latter would possess ownership of the system after the 25-year concession period. Meanwhile, the DOTC would assume all administrative functions, such as the regulation of fares and operations, leaving the MRTC responsibility over construction and maintenance of the system as well as the procurement of spare parts for trains. MRTC would later transfer the responsibility of maintaining the system to the DOTC in November 2010. In exchange, the DOTC would pay the MRTC monthly fees for a certain number of years to reimburse any incurred costs.[1]

Construction began on October 15, 1996, with a BLT agreement signed between the Philippine government and the MRTC.[24] An amended turnkey agreement was later signed on September 16, 1997, with Sumitomo Corporation and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. Sumitomo and Mitsubishi subcontracted EEI Corporation and AsiaKonstrukt for the civil works.[27] A separate agreement was signed with ČKD Dopravní Systémy (ČKD Tatra, now part of Siemens AG), the leading builder of trams and light rail vehicles for the Eastern Bloc, on rolling stock. MRTC also retained the services of ICF Kaiser Engineers and Constructors to provide program management and technical oversight of the services for the design, construction management, and commissioning.[1] MRTC would later sign a maintenance agreement with Sumitomo and Mitsubishi for the maintenance of the line on December 10 of the same year.[28]

During construction, the MRTC oversaw the design, construction, equipping, testing, and commissioning, while the DOTC oversaw technical supervision of the project activities covered by the BLT contract between the DOTC and MRTC. The DOTC also sought the services of SYSTRA, a French consultant firm, with regards to the technical competence, experience and track record in the construction and operations.[1]

On December 15, 1999, the initial section from North Avenue to Buendia was inaugurated by President Joseph Estrada,[29] with all remaining stations opening on July 20, 2000, a little over a month past the original deadline, due to DOTC's inclusion of additional work orders such as the Tramo overpass in Pasay leading to Ninoy Aquino International Airport.[30] However, ridership was initially far below expectations when the line was still partially open, with passengers complaining of the tickets' steep price and the general lack of connectivity of the stations with other modes of public transportation.[31] Passengers' complaints of high ticket prices pointed to the maximum fare of ₱34, which at the time was significantly higher than a comparable journey on those lines operated by the LRTA and the PNR or a similar bus ride along EDSA. Although the MRTC projected 300,000–400,000 passengers riding the system daily, in the first month of operation the system saw a ridership of only 40,000 passengers daily (the ridership improved quickly, however, when passengers experienced significantly faster and convenient travel along EDSA, which experience soon spread by word of mouth).[32] The system was also initially criticized as a white elephant, comparing it to the Manila Light Rail Transit System and the Metro Manila Skyway.[33] To alleviate passenger complaints, the MRTC later reduced passenger fares to ₱15, as per the request of then-President Joseph Estrada and a subsequent government subsidy.

Overcrowding and later decline

| Firm | From | Until | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sumitomo Corporation Mitsubishi Heavy Industries |

January 1, 2000 | October 19, 2012 | |

| PH Trams Comm Builders & Technology |

October 20, 2012 | September 3, 2013 | |

| Autre Porte Technique Global Inc. | September 4, 2013 | July 4, 2015 | |

| Schunk Bahn-und Industrietechnik Comm Builders & Technology |

July 5, 2015 | January 7, 2016 | |

| Busan Universal Rail, Inc. | January 8, 2016 | November 5, 2017 | |

| Department of Transportation Maintenance Transition Team |

November 6, 2017 | April 30, 2019 | |

| Sumitomo Corporation Mitsubishi Heavy Industries |

May 1, 2019 | present | |

MRTC projected a capacity breach in the system by 2002. By 2004, the line had the highest ridership of the three lines, with 400,000 passengers daily. By early 2012, the system was carrying around 550,000 to 600,000 commuters during weekdays and was often badly overcrowded during peak times of access during the day and night. The line operated beyond its original designed capacity from 2004 to 2019, and since 2022.[35] In 2011, Sumitomo, through TES Philippines, issued a warning about the overcrowding situation of the line, in which a failure to immediately upgrade the line's trains and systems would result in damage to the trains and systems.[36]

By October 2012, DOTC removed Sumitomo as the maintenance provider of the line due to the high costs of the contract. With the entry of the joint venture of Philippine Trans Rail Management and Services Corporation (PH Trams) and Comm Builders & Technology Philippines Corporation (CB&T) as the maintenance provider in 2012,[37] and APT Global in 2013,[38] it marked the start of the deterioration of the line due to poor maintenance by the aforementioned maintenance providers that DOTC appointed. In 2014, there were reported daily incidents and disruptions, and a derailment of one train coach on August 13 of that year.[39] The government of Benigno Aquino III had been planning to buy the line from the MRT Corporation (MRTC), the private concessionaire that built the line, and then bid it out to private bidders. The Aquino government accused the MRTC of neglecting and not improving the services of the line under its watch.[40]

In February 2016, the Philippine Senate released a report stating that DOTC Secretary Jun Abaya and other DOTC officials "may have violated" the Anti-Graft and Corrupt Practices Act in relation to questionable contracts with the subsequent maintenance providers.[41] In a Senate report where the line's condition was found to be in "poor maintenance" as per studies made by MTR HK, DOTC officials were reported to be involved in graft in relation to questionable contracts, especially those for the maintenance of the line.[42]

The DOTC tried to bid out a three-year maintenance contract in 2014 and 2015, but both biddings failed because no bidders submitted a bid.[43][44] Through a negotiated procurement,[45] the Busan joint venture, a joint venture of Busan Transportation Corporation, Edison Development & Construction, Tramat Mercantile Inc., TMICorp Inc., and Castan Corporation, was awarded a three-year maintenance contract by the DOTC. The contract started in January 2016 and was slated to end by January 2019.[46] In 2017, DOTC's succeeding agency, the Department of Transportation (DOTr) attributed the operation's disruptions of the rail system to the Busan joint venture, later known as Busan Universal Rail, Inc. (BURI), with DOTr Transport Undersecretary for Rails Cesar Chavez noting 98 service interruptions and 833 passenger unloadings (or average of twice daily) as well as train derailments in April–June 2017.[34] BURI insisted that the disruptions the railway line was experiencing is due to "inherent design and quality concerns" and not to poor maintenance or normal tear or wear. It said that glitches started occurring since 2000, a claim that MRTC dismissed when Sumitomo was maintaining the system.[47] The maintenance contract was terminated on November 6, 2017.[48]

Capacity expansion

Due to the high ridership of the line, a proposal under study by the DOTC and NEDA proposed to double the current capacity by acquiring additional light rail vehicles to accommodate over 520,000 passengers a day.[50]

In January 2014, the DOTC entered into a contract with CNR Dalian for the procurement of 48 light rail vehicles. The trains, commonly referred to as the Dalian trains, were delivered in batches from 2015 to 2017. The introduction of the new trains would have allowed the line to handle over 800,000 passengers.[51] The first train was scheduled to be in revenue service before April 2016[52][53] but delays in its 5,000-kilometer (3,100 mi) test run had delayed its deployment for revenue service.[54][55] Nevertheless, the trains entered revenue service on May 7, 2016.[56]

However, the trains became a subject of controversy, citing its incompatibility with the signalling system and weight limits on tracks. Later, it was revealed that several adjustments to the Dalian trains are required prior to revenue run deployment.[57] The train manufacturer CRRC Dalian has agreed to amend the train specifications to match the contract terms at no cost, and will do so in the soonest possible time.[58] Due to the trains undergoing the said adjustments, they were slowly introduced into regular operations, which led to the start of the gradual deployment on October 27, 2018.[59]

Aside from the procurement of the new trains, the capacity expansion project included the upgrading of the ancillary systems such as the power supply, overhead lines, the extension of the pocket track near Taft Avenue station and the modification of the turn back siding north of the North Avenue station.[60][61] The original plan also included the upgrading of the signalling system.[60] These upgrades, except for the upgrades to the Taft Avenue pocket track and the North Avenue turn back siding, would only be realized as part of the line's 2019–2021 rehabilitation.

Plans were also laid to increase the number of cars in each train set, from the current 3-car configuration to 4-car configuration, which also increases the number of passengers being accommodated for each trip, from 1,182 passengers to 1,576 passengers for each train set.[62] The first mention of this plan was in 2013, during the procurement of the new trains.[6] However, in January 2016, a railway expert warned that the power supply at that time was not capable of handling four-car train operations.[63] Despite this, four-car operations were first tested in a Dalian train in May 2016.[64] After the rehabilitation of the line which included the upgrading of the power supply, a dynamic test run for the use of four-car trains for regular operations was conducted in March 2022.[65] Regular four-car operations began in the same month, initially deploying two trains for daily operations, subsequently increased to four.[66][67] Although full conversion was initially planned to be achieved by 2023,[68] all trains reverted to the existing configuration a few months after the months-long free rides ended. Nevertheless, this plan is being pitched once again to increase the line's capacity to 500,000 passengers a day.[49]

Rehabilitation

As early as 2011, there were proposals to rehabilitate the line. An unsolicited proposal were made by Metro Pacific Investments in 2011 at a cost of ₱25.1 billion. Another proposal was presented in 2014 at a cost of ₱23.3 billion.[70] In 2017, in the wake of various daily service interruptions in the line, San Miguel Corporation expressed its interest to rehabilitate the line.[71] That same year, Metro Pacific submitted another ₱20 billion proposal to rehabilitate, operate and maintain the line.[72] These proposals however would be rejected by the government.

Following the termination of the maintenance contract with Busan Universal Rail, Inc., the DOTr announced on November 29, 2017, that a government-to-government agreement between the Philippines and Japan would be signed by the end of that year, paving the way for Sumitomo Corporation to return as the maintenance provider of the line. The three-year contract would cover the rehabilitation and maintenance of the line.[73] The ₱22 billion project, partly funded by a ₱18 billion loan from the Japan International Cooperation Agency,[11] was approved by the Investment Coordination Committee (ICC) board of the National Economic and Development Authority (NEDA) on August 17, 2018.[74] It intended to rehabilitate and upgrade the existing systems and trains, for the line to return to its original high-grade design. The project was part of the Build! Build! Build! infrastructure program.

On November 8, 2018, the loan agreement for the project was signed,[11] while the rehabilitation and maintenance contract was signed on December 28.[75] The project was initially slated to start by January 2019,[76] but the implementation of a re-enacted government budget for 2019 and finalization of documents caused repeated delays on when the project could start,[77][78] which only started on May 1, 2019.[12]

Under the 43-month contract, which was undertaken by Sumitomo, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Engineering (part of the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries group),[79] and TES Philippines, rehabilitation works were to be done within 26 months.[80] It covers the overhaul of all MRTC Class 3000 vehicles[lower-alpha 1], repairs on the escalators and elevators, rail replacement, upgrades on the signalling and communication systems, power supply, overhead systems, maintenance and station equipment.[81] After the rehabilitation, a 17-month maintenance contract will be undertaken by the Japanese firms.[79] The contract was originally slated to end by December 2022, or 43 months after the start of the rehabilitation,[75] but was moved to May 31, 2023.[49][79]

The rehabilitation was originally scheduled to be completed by July 2021. However, delays brought by the COVID-19 pandemic[82] delayed its completion to December 2021.[83] On February 28, 2022, Transportation Secretary Arthur Tugade announced that the rehabilitation was finished in December 2021.[84] On March 22, President Rodrigo Duterte and Secretary Tugade inaugurated the newly rehabilitated line at a completion ceremony held at Shaw Boulevard station.[13][79] As part of its completion, free rides were offered for three months.[85][86]

On May 26, 2023, a ₱6.9 billion loan was signed by the governments of Japan and the Philippines for the second phase of the project, covering the line's continued maintenance and its connection to the North Triangle Common Station with the lines that would interchange at that station.[87] Four days later, DOTr and Sumitomo signed a contract to extend the latter's maintenance in the railway line until July 2025.[88]

Station facilities, amenities, and services

With the exception of Buendia and Ayala stations, and the platform level of Taft Avenue and Boni stations, all stations are situated above ground, taking advantage of EDSA's topology.[89]

Station layout and accessibility

The stations have a standard layout, with a concourse level and a platform level.[60] The concourse is usually above the platform, with stairs, escalators and elevators leading down to the platform level. Station concourses contain ticket booths, which is separated from the platform level by fare gates.[24] Some stations, such as Araneta Center-Cubao, are connected at concourse level to nearby buildings, such as shopping malls, for easier accessibility. Most stations are also barrier-free inside and outside the station, and trains have spaces for passengers using wheelchairs.[24]

Stations either have island platforms, such as Taft Avenue, Buendia, Boni Avenue, and Shaw Boulevard stations, and side platforms, such as from Magallanes station to Ayala stations, Guadalupe, and from Ortigas to North Avenue stations. Due to the very high patronage of the line, before the pandemic, part of the platform corresponding to the first car of the train is cordoned off for the use of senior citizens, pregnant women, children who are below 4 feet (1.2 m) and age seven, and disabled passengers. Since 2021, the first two doors of the first car of the train has been allotted as a priority section for the aforementioned passengers.[90]

The station platforms have a standard length of 130 meters (426 ft 6 in),[60] designed to accommodate trains with four cars.[68] The stations are also designed to occupy the entire span of EDSA, allowing passengers to safely cross between one end of the road and the other.[24]

The line has a total of 46 escalators and 34 elevators across all 13 stations. Prior to the rehabilitation, only few escalators and elevators were operational. The escalators and elevators were rehabilitated as part of the rehabilitation of the line. The project started in June 2019 and was completed on August 20, 2020.[91]

In February 2012, the line allowed folding bicycles to be brought into trains provided that the wheels do not exceed more than 20 inches (51 cm) in diameter.[92]

Platform screen doors were also planned for each station, with the plans for the platform doors were laid out as early as 2013,[93] however, these plans were delayed until it was reconsidered in 2017.[94]

Shops and services

Inside the concourse of all stations are stalls or shops where people can buy food or drinks. Stalls vary by station, and some have fast food stalls. The number of stalls also varies by station, and stations tend to have a wide variety, especially in stations such as Ayala and Shaw Boulevard.

Stations such as Taft Avenue and North Avenue are connected to or are near shopping malls and/or other large shopping areas, where commuters are offered more shopping varieties.

Since November 19, 2001, in cooperation with the Philippine Daily Inquirer, passengers have been offered copies of the Inquirer Libre, a free, tabloid-size, Tagalog version of the Inquirer, which is available at all stations.[95] In 2014, Pilipino Mirror also started distributing free tabloid newspapers.

Safety and security

The line's safety was affirmed in a 2004 World Bank paper prepared by Halcrow, describing the overall state of metro rail transit operations in Manila as being "good".[96] However, since the DOTr took over maintenance of the train system in 2012, the safety and reliability of the system has been questioned, with experts calling it "an accident waiting to happen." While several incidents and accidents were reported between 2012 and 2014, they did not deter commuters from using the system.[97] The Philippine government, meanwhile, continues to assert that the system is safe overall despite those incidents and accidents.[98]

Although the line operated significantly above its designed capacity of between 360,000 and 380,000 passengers per day from 2004[10] to 2019 and government officials have admitted that capacity and system upgrades are overdue,[99] although the DOTr has never acted on the numerous capacity expansion proposals of the private owners. In the absence of major investment in improving system safety and reliability, DOTr has resorted to experimenting with and implementing other solutions to reduce strain on the system, including crowd management on station platforms[100] and the proposed implementation of peak-hour express train service.[101] However, some of these solutions, such as platform crowd management, are unpopular with passengers.[102]

For safety and security reasons, persons who are visibly intoxicated, insane and/or under the influence of controlled substances, persons carrying flammable materials and/or explosives, and persons carrying bulky objects or items over 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) tall and/or wide are prohibited from entering the line.[103] Products in tin cans are also prohibited on board, citing the possibility of home-made bombs being concealed inside the cans.[104]

In late 2000 and early 2001, in response to the Rizal Day bombings and the September 11 attacks, security was increased. Following a vandalism incident in May 2021,[105] the number of security personnel deployed across all stations was increased and a patrol car was deployed for added security.[106] After a bomb threat incident on September 8, 2023, DOTr formed an inter-agency task force to enhance security across all transportation sectors.[107] Units of the Philippine National Police[108] and security police provided by private companies can be found in all stations. All stations have a head guard. Some stations may also have a deployed K9 bomb-sniffing dog. The line also employs the use of closed-circuit television inside all stations to monitor suspicious activities.

Pets have been allowed to ride since July 12, 2021, but pets must be placed inside a carrier bag before boarding a train.[109]

Ridership

The original designed ridership of the line is 350,000, yet as the years passed, the number doubled from 450,000 daily passengers in 2006–2007 to 490,000 passengers in 2008 and up to 500,000 passengers from 2010 to 2012, with record numbers reaching as high as 620,000 from 2012 to 2013, before declining to 560,000 in 2014.[35] The high ridership of the line is due to the time consumed when commuting via EDSA, as well as the speed of the trains reaching up to 60 kilometers per hour (37 mph), and connectivity to Metro Manila's major transport hubs, railway lines, and central business districts, which results to a reduced commuting travel time and an increase in ridership. The daily ridership of the line can reach as much as 300,000 to 500,000 passengers from 2012 to 2016, despite poor maintenance and long lines, causing the government to launch bus services, known as MRT Buses, around its stations, to serve as alternatives for 900,000 to 1 million passengers. In addition to the rising daily ridership that continues to exceed the line's designed capacity, and as the government continues to implement the metro line's capacity expansion project, it aims to reach a ridership of 800,000 daily passengers as all of the new trains from China will be added to its current fleet.[51]

Ridership declined in 2015, with a daily average of 327,314 passengers, which is lower than the 2014 record of 464,871 daily passengers on average. The ridership increased slightly in 2016, with a daily average of 370,036 passengers, and the highest recorded daily ridership of 517,929 in December of that year. However, ridership started to decline by 2017 due to poor maintenance and daily breakdowns. Ridership continued to decline through 2018 and 2019, until a significant drop in ridership was recorded in 2020 due to capacity limitations brought by the COVID-19 pandemic, serving 70,000 to 150,000 passengers daily.[110] It previously served almost 40,000 passengers in June 2020,[111] and 150,000 passengers in January 2021.[112] Until February 2022, the line operated at a limited capacity before capacity limitations were removed by March 1, 2022.

Ridership slightly increased in 2021, servicing 136,935 daily passengers on average and 45,675,884 passengers throughout the same year, due to the increased capacity in November 2021.[113] After the completion of the rehabilitation project in 2022, the line offered free rides to commuters in three months. This, in turn, increased the ridership of the line.[114] By the end of the free rides, a total of 28,624,982 passengers rode the line. It also recorded a daily average of 318,055 passengers in the same period.[115] By the end of the year, the line carried 98,330,683 passengers, its highest since the 2019–2021 rehabilitation.[2]

Statistics

Data from the Department of Transportation (DOTr).[110]

| † | Highest recorded ridership |

| Year | Daily average | % change | Annual ridership | % change | Highest single-day ridership |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1999[lower-alpha 2] | 23,057 | 368,916 | 39,760 (December 23, 1999) | ||

| 2000 | 109,449 | 39,401,465 | 296,969 (December 22, 2000) | ||

| 2001 | 250,728 | 90,262,148 | 391,187 (December 14, 2001) | ||

| 2002 | 282,993 | 102,443,564 | 417,059 (July 1, 2002) | ||

| 2003 | 312,043 | 112,647,474 | 438,809 (December 19, 2003) | ||

| 2004 | 338,431 | 122,512,169 | 452,926 (December 16, 2004) | ||

| 2005 | 356,673 | 128,758,894 | 465,203 (September 7, 2005) | ||

| 2006 | 374,436 | 135,171,387 | 488,733 (December 15, 2006) | ||

| 2007 | 395,806 | 142,886,057 | 539,813 (December 21, 2007) | ||

| 2008 | 413,220 | 149,585,563 | 527,530 (October 15, 2008) | ||

| 2009 | 419,728 | 151,521,764 | 560,637 (September 15, 2009) | ||

| 2010 | 424,041 | 153,078,770 | 552,509 (October 15, 2010) | ||

| 2011 | 439,906 | 158,806,049 | 577,015 (October 14, 2011) | ||

| 2012 | 481,918 | 174,454,146 | 622,880 (August 17, 2012) † | ||

| 2013 | 487,696 † | 176,058,278 † | 621,913 (October 25, 2013) | ||

| 2014 | 464,871 | 167,818,336 | 614,807 (February 14, 2014) | ||

| 2015 | 327,314 | 118,160,484 | 455,164 (February 25, 2015) | ||

| 2016 | 370,036 | 133,952,890 | 517,929 (December 16, 2016) | ||

| 2017 | 388,233 | 140,152,161 | 506,001 (February 10, 2017) | ||

| 2018 | 289,654 | 104,275,362 | 390,325 (January 12, 2018) | ||

| 2019 | 270,794 | 96,932,972 | 359,447 (January 25, 2019) | ||

| 2020 | 121,839 | 31,799,959 | 324,803 (January 24, 2020) | ||

| 2021[113] | 136,935 | 45,675,884 | 223,739 (December 23, 2021) | ||

| 2022 | 273,141 | 98,330,683 | 389,784 (June 17, 2022) |

Fares and ticketing

The line, like all other lines in Metro Manila, uses a distance-based fare structure, with fares ranging from 13 to 28 pesos (29 to 63 U.S. cents), depending on the destination. Commuters who ride the line are charged ₱13 for the first two stations, ₱16 for 3–4 stations, ₱20 for 5–7 stations, ₱24 for 8–10 stations and ₱28 for 11 stations or the entire line. Children below 1.02 meters (3 ft 4 in) (the height of a fare gate) may ride for free.

Fares are free of charge every March 8 (International Women's Day; free rides exclusive for women),[116] June 12 (Independence Day),[117][118] and December 30 (Rizal Day) on limited time slots.[119]

The line, along with the LRT Line 2 and Philippine National Railways lines also offered free rides to students starting July 1, 2019,[120] but students must register to avail a student pass.[121] However, the free rides for students stopped in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic as distance learning was implemented as a mode of learning during the pandemic.[110] With the shift towards the return of physical face-to-face classes, a plan to return the free rides to students by August 2022 was announced;[122] however, free rides for students will only be limited to the LRT Line 2 due to more losses that the government will incur as a consequence of the free rides.[123] Instead, the line will offer a 20% fare discount for students that wish to avail.[124]

Types of tickets

Magnetic tickets (1999–2015)

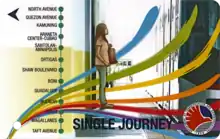

Two types of tickets exist: a single-journey (one-way) ticket whose cost is dependent on the destination, and a stored-value (multiple-use) ticket for 100 pesos. The 200-peso & 500-peso stored-value tickets were issued in the past, but have since been phased out. The single-journey ticket is valid only on the date of purchase. Meanwhile, the stored-value ticket is valid for three months from date of first use.[103]

The tickets come in several incarnations: these include tickets bearing the portraits of former presidents Joseph Estrada and Gloria Macapagal Arroyo,[125] which have since been phased out, and one bearing the logos of the DOTC and the MRTC. Ticket shortages are common: in 2005, the MRTC was forced to recycle tickets bearing Estrada's portrait to address critical ticket shortages, even resorting to borrowing stored-value tickets from the LRTA[126] and even cutting unusable tickets in half for use as manual passes. Shortages were also reported in 2012,[127] and the DOTC was working on procuring additional tickets in 2014.[128] Because of the ticket shortages, it had become common practice for regular passengers to purchase several stored-value tickets at a time, though ticket shortages still persist.[129]

Although it has partnered with private telecommunications companies in experimenting with RFID technology as an alternative ticketing system in the past,[130][131] these were phased out in 2009.[132]

Beep cards (2015–present)

Currently, inter-operable beep cards with similar-to-the-previous single-journey and stored-value ticket types are now issued, along with the deployment of brand-new ticketing machines that replaced the barely-used ticketing machines that has been in place since the line's inauguration. The beep, tap-and-go tickets, loadable up to ₱10,000, became available to use in all stations of the line on October 3, 2015.[133]

A shortage of the stored value cards was reported in 2022 due to the ongoing global chip shortage caused by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[134][135]

Fare adjustment

Adjusting passenger fares was ordered by President Joseph Estrada as a means to boost flagging ridership figures,[136] and the issue of fares both historically and in the present day continues to be a contentious political issue involving officials at even the highest levels of government.

Current fare levels were set on January 4, 2015, as a consequence of DOTr (formerly DOTC) having to increase fares for LRT Line 1 as per their concession agreement with MPIC-Ayala, with fare hikes delayed for several years despite inflation and rising operating costs.[137] Prior to the current fares levels, fares were set on July 15, 2000, under the orders of then President Estrada; this was intended to have the line become competitive against other modes of transport,[138] but had the effect of causing revenue shortfalls which the government shouldered. While originally set to last only until January 2001,[138] the new fare structure persisted due to strong public opposition against increasing fares,[139] especially as ridership increased significantly after lower fares were implemented.[136] In 2022, when the line waived its fares, ridership also increased.[140] These lower fares—which are only slightly more expensive than jeepney fares—ended up being financed through large government subsidies amounting to around ₱45 per passenger,[139][141] and which for both the MRT and LRT reached ₱75 billion for the 10-year period between 2004 and 2014.[142] Without subsidies, the cost of a single trip is estimated at ₱60,[141] and a ₱10 increase in fares would yield additional monthly revenues of ₱2–3 billion a month.[143]

Passenger fare subsidies are unpopular outside Metro Manila, with subsidy opponents claiming that their taxes are being used to subsidize Metro Manila commuters without any benefit to the countryside, and that the fare subsidies should be used for infrastructure improvements in the rest of the country.[144] In his 2013 State of the Nation Address, President Benigno Aquino III claimed that it would be unfair for non-Metro Manila residents to use their taxes to subsidize the LRT and MRT.[145] However, supporters of the subsidies claimed that the rest of the country benefits economically from efficient transportation in Metro Manila.[146]

In January 2023, a petition was filed for a ₱4–6 fare hike due to a major net loss incurred; in 2022, the incurred revenue was only ₱1.11 billion whereas the expenses amounted to roughly ₱8.97 billion, resulting in a loss of ₱7.86 billion. In the petition, the MRT-3 management said that fare revenues were never enough to compensate the MRTC to cover initial investment in the construction, operations, and maintenance of the line.[147]

Rolling stock

The line runs light rail vehicles (LRV) in a regular three-car configuration. Four-car trains began operating by March 2022, although most trains remain running in three cars.[66] The DOTr plans to convert all three-car trains to four-car trains by 2023.[68] Two train types run in the line, the latest being those purchased from CRRC Dalian, under the Aquino administration.

The line has a total of 121 light rail vehicles. 73 of which were made in the Czech Republic by ČKD (now part of Siemens AG)[1] and were purchased with export financing from the Czech government.[148] One ČKD train car was damaged following a derailment of a train in 2014. Another 48 were made by CRRC Dalian in China that were purchased at a cost of ₱3.8 billion. Trains have a capacity of 1,182 passengers,[1] expandable to 1,576,[149] which is a little bigger than the normal capacity of LRT Line 1 first generation rolling stock that has a capacity with the same configuration of 1,122 passengers, although trains came with air conditioning.[lower-alpha 3] Despite this, it is designed to carry in excess of 23,000 passengers per hour per direction (PPHPD), and is expandable to accommodate 48,000 passengers per hour per direction.[1]

The plans for new rolling stock has been an issue for the MRT during the Aquino administration under DOTC's leadership of then Secretary Joseph Emilio Abaya, with plans to acquire 52-second-hand LRVs offered from Madrid Metro in Spain with a budget of ₱8.43 billion,[150] along with a proposal from Inekon Trams in 2013.[151] However, undisclosed issues and train incompatibility issues regarding the project, the project was downgraded to 48 LRVs, with the contract having CRRC Dalian supply 48 new LRVs.

The deployment of the Dalian trainsets was delayed due to several factors, including weight limits on existing tracks and inconsistencies in production, which has since been corrected. On October 27, 2018, DOTr started the gradual deployment of the 2nd-generation trains.[59] Currently, none of the Dalian trains are in operation.[113]

The trains are designed to run at a maximum speed of 65 kilometers per hour (40 mph), but currently run at a maximum safe speed of 60 kilometers per hour (37 mph), though some areas are limited to a speed of 40 to 50 kilometers per hour (25 to 31 mph) like turnouts. Until 2014, all trains ran at the maximum speed until speed restrictions were implemented following a derailment incident of a train coach at Taft Avenue station on August 13 of that year, in which the maximum speed was restricted to 40 kilometers per hour (25 mph).[152] By 2017, it was subsequently downgraded to 30 kilometers per hour (19 mph).[153] After the completion of a rail replacement program, the operating speed was gradually increased from 30 kilometers per hour (19 mph), to 40 kilometers per hour (25 mph) on October 1, 2020,[154] to 50 kilometers per hour (31 mph) on November 3,[155] and to 60 kilometers per hour (37 mph) on December 7.[156]

Due to poor maintenance by the previous maintenance contractors, the line previously operated with 7–10-minute headways under the DOTr orders,[1] and the line's passenger volume operated at 15,000–18,000 passengers per hour per direction before the COVID-19 pandemic. With the enhancements and rehabilitation, the delays were gradually shortened, and the passenger volume is expected to increase to 19,000–25,000 passengers per hour per direction with the introduction of four-car trains and the lifting of capacity restrictions brought by the COVID-19 pandemic.[157]

In early 2018, the lack of spare parts for the trains decreased the number of usable trains to just 3 to 7 operational trains running during peak hours.[158][159] The Department of Transportation (DOTr) attributed this to the previous maintenance provider, Busan Universal Rail Inc. (BURI), for failing to provide enough spare parts for the trains.[160] However, by April 2018, after maintenance works were done, the usabale trains were increased to 14–16.[161]

Due to aging air conditioning units that have been in place since the line's inauguration and complaints of uncomfortable indoor temperatures from riders, the air-conditioning units for the first-generation trainsets were first replaced in 2008 during the line's first general overhaul in 2008 to 2009.[162] In 2017, the second replacement of the air conditioning units commenced, with new units ordered from Thermo King. The replacement of these units were finished on June 18, 2021, as part of the line's rehabilitation project.[163]

The Passenger Assist Railway Display System (PARDS), a passenger information system powered by LCD screens installed near the ceiling of the train that shows news, advertisements, current train location, arrivals and station layouts, are already installed inside the first-generation trains. PARDS is also installed on trains on LRT lines 1 and 2.[164]

Depot

The line maintains an underground depot in Quezon City near North Avenue station. Above the depot is TriNoma, a shopping mall owned by the Ayala Corporation. The depot occupies 84,444 square meters (908,950 sq ft; 8.4444 ha) of space and serves as the center of operations and maintenance. It is connected to the mainline through a spur line. The depot is capable of storing 81 light rail vehicles, with the option to expand to include 40 more vehicles as demand arises.[60] They are parked on nine sets of tracks, which converge onto the spur route and later on to the main network.[1] However, a lot of rail tracks for storage inside the depot owned by MRTC were taken by DOTC (now DOTr) to repair broken rails,[165] as DOTC's previous maintenance provider did not purchase spare rails. These rails have since been replaced during the rehabilitation done along the entire line by Sumitomo.

Other infrastructure

Signalling

The line uses the CITYFLO 250 fixed block signalling solution supplied by Alstom (formerly Bombardier Transportation),[4] designed for light rapid transit operations with on-board automatic train protection (ATP) system on trains.[166][167] Aside from the ATP system, the signalling system consists of train detection through track circuits, EBI Screen 900 centralized traffic control, and computer-based interlocking.[168][1]

Adtranz, later Bombardier Transportation, designed and supplied the original signalling system of the line, and maintained it from 2000 to 2012.[4][169] The firm owns the proprietary rights to supply new components for the system. Plans were laid to upgrade the signalling system were laid in 2015. That same year, Bombardier, through its Thai subsidiary Bombardier Transportation Signal (Thailand), was awarded the contract to upgrade the system's local control system. The upgrade replaced the MAN 900 system with the EBI Screen 900 system with modern computers and fiber optic technology.[170]

The previous maintenance providers failed to properly maintain the signalling system and used non-OEM parts to save costs. This in turn, caused many problems within the system which became among the top three reasons of service interruptions on the line.[4] Plans to upgrade the signalling system were restarted in 2018, when the Department of Transportation (DOTr) signed a memorandum of understanding (MoU) with Bombardier Transportation on February 9, 2018, for the procurement of the Original Equipment Manufacturer (OEM) of the signalling equipment and spare parts.[4] Included in the MoU was a two-year maintenance contract[4] that was later cancelled in May 2019 due to the rehabilitation program which included the maintenance of the signalling system by Sumitomo.[171]

The 2019–2021 upgrade included the replacement of copper cables with fiber optic cables,[172] installation of 71 new signal lights,[173] new interlocking equipment, new point machines, new track circuits (including tuning units which form part of the track circuits),[174] and other wayside equipment.[175] Works continued during the acquisition of Bombardier Transportation by Alstom in January 2021. The upgraded system was commissioned on October 24, 2021.[5]

Tracks

_2022-02-12.jpg.webp)

The standard gauge tracks consist of 54-kilogram-per-meter (36 lb/ft) rails designed to the UIC 54 rail profile,[1][6] which are welded together to form a long-welded rail.[69] Some rails located in the turnouts have fishplates bolted at the ends of the rail. These are laid on sections of the line with ballasted and concrete plinth sections.[60] Sections with track ballast are located on at-grade sections and the underground portion of the line (except Buendia station and the turnouts south of the station), while plinth sections are located at elevated sections of the line. The tracks on ballasted sections are supported by concrete sleepers.[60] The rehabilitation of the line led to the introduction of fiber-reinforced foam urethane (FFU) railway sleepers. FFU sleepers are found at the line's depot and the turnouts near Taft Avenue station.[176]

Plans to replace the rail tracks were laid in 2015. Replacement works in certain sections of the line were conducted in February and March of that year.[177][178] In January 2015, the joint venture of Jorgman, Daewoo, and MBTech Group was awarded the ₱61.5 million contract for the major replacement works. The joint venture supplied 7,296 pieces of 12-meter (39 ft) rails.[179]

However, the rails would later be worn out. A rail replacement program started on November 4, 2019, as part of a rehabilitation program.[69] 4,053 pieces of 18-meter (59 ft) rails assembled by the Nippon Steel Corporation in Fukuoka, Japan were used for the replacement program.[180] Rail replacement works were suspended during the enhanced community quarantine in Luzon, but works resumed in April 2020 and the replacement was fast-tracked.[181][182] The replacement program was slated to be completed by February 2021, but was completed five months early, in September 2020.[182] The turnouts near the Taft Avenue station were repaired in October and November 2020.[183][184] The rail replacement was intended to increase the operating speed from 30 kilometers per hour (19 mph) to 60 kilometers per hour (37 mph) and was achieved on December 7, 2020.[156]

Plans and proposals

Privatization

In November 2022, the Department of Transportation said that it is considering to privatize the operations and maintenance of the line to enhance efficiency, reduce operating costs, and keep fares affordable. The rail lines assets will remain owned by the government, similar to the LRT Line 1.[185] Such a plan was announced as early as 2017.[186]

Southern and western extension

In a feasibility study in 2009 and in 2015, launched by Japan International Cooperation Agency, along with the Department of Transportation, the Transport and Traffic Planners (TTPI) Inc.[187] and other Japanese and local railway officials, launched a plan to extend the present MRT line's southern end, by constructing a 2.2-kilometer (1.4 mi) at-grade and underground segment, from Taft Avenue station to the SM Mall of Asia complex.[188] Plans were also laid out to add another station, by traversing through Macapagal Boulevard and linking the line to the Parañaque Integrated Terminal Exchange, therefore adding another 3.1 kilometers (1.9 mi) to the main line. The study also included a planned 7.2-kilometer (4.5 mi) extension to the northern and western cities of Navotas, Southern Caloocan, and Malabon, which is also included to the planned merging project with the LRT Line 1, and connecting it to the North–South Commuter Railway Caloocan station.[188]

Due to the numerous problems surrounding the project, such as right-of-way and cost issues, the government decided to presumably scrap the extension plans, and look for alternatives instead, such as the planned Integrated Pasay Monorail project by the Pasay City LGU and SM Investments, starting from the Taft Avenue station to SM Mall of Asia.[189]

Line merge with LRT Line 1

Although Phase 1 of the line (Taft Avenue to North Avenue) has already been built, the route envisioned by the DOTC and the government, in general, was for it to traverse the entire length of EDSA (from Monumento to Taft Avenue), eventually meeting with the LRT 1 at Monumento in Caloocan (Phase 2) to create a seamless rail loop around Metro Manila. The expansion has been shelved by then President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo in favor of the LRT Line 1's extension from Monumento to a new common station that it will share with at North Avenue, thus closing the loop. However, this move of President Arroyo to take away Phase 2 had proven to be ill-advised as the ridership is very low at only about 30,000 passengers a day. The southern terminus of the MRT Line 7 (originally Line 4 along Quezon Avenue., but had since changed route several times), which will link Quezon City, Caloocan (north), and San Jose del Monte City, Bulacan will be sharing the same station.

The National Economic and Development Authority as well as then President Arroyo herself have said that the link at North Avenue is a national priority, since it would not only provide seamless service between the LRT Line 1 and MRT Line 3, but would also help decongest Metro Manila.[190] It is estimated that by 2010, when the extension is completed, some 684,000 commuters would use the line every day from the present 400,000, and traffic congestion on EDSA would be cut by as much as 50%.[191]

Proposals to fully unite LRT-1 and MRT-3 operations and systems have been pitched but has not been pursued so far. Feasibility tests for this proposition included LRT-1 trains visiting MRT 3 depot facilities and running them on the entire line. Even if the physical infrastructure connecting the two rail systems are in place and successfully tested,[192] commuters have to go down at the Roosevelt station of LRT Line 1 and walk over or take a tricycle or jeepney for the 1-kilometer (0.62 mi) distance to the Trinoma terminal of MRT Line 3.[193] In 2011, a year after the completion of the loop, the then-Department of Transportation and Communications, under Secretary Jose de Jesus, launched an auction for a temporary five-year operations and maintenance contract for the MRT-3 and LRT-1. The bidding was set by July 2011. Over 21 companies from around the world expressed interest to bid which included Metro Pacific Investments, Sumitomo Corporation, Siemens, DMCI Holdings, San Miguel Corporation, and others.[194] After de Jesus resigned from the DOTC,[195] his successor, Mar Roxas, halted the auction process and was later shelved.[196]

Transfer of operations from MRTC to LRTA

A new study for the Metro Manila Rail Network has been unveiled by DOTC Undersecretary for Public Information Dante Velasco that LRT 1, LRT 2, and MRT 3 will be placed under the management of the Light Rail Transit Authority (LRTA). This is due to maintenance cost issues for LRT 1's maintenance cost, which is approximately ₱35 million, along with LRT Line 2's ₱25 million and MRT Line 3's ₱54 million maintenance costs. Another reason for this study is for the unification of the lines. According to DOTC Undersecretary for Rails Glicerio Sicat, the transfer was set by the government in June 2011.[197] However, it is unlikely that the private owners, MRTC, will approve this plan.

On January 13, 2011, Light Rail Transit Authority Chief Rafael S. Rodriguez took over as officer-in-charge of the line in preparation for the integration of operations of the three lines,[198] but with the entry of a new leadership into the DOTC that year and in 2012, the transfer was deemed not likely to happen; however, in April 2012, a LRT 1 trainset made the first trial journey to the MRT 3 depot.[199]

On May 26, 2014, the line's general manager Al Vitangcol was sacked by Transportation and Communication Secretary Joseph Emilio Abaya, and was replaced by LRTA Administrator Honorito Chaneco as officer-in-charge. The move came after Vitangcol was accused by the ambassador of the Czech Republic of extortion and for awarding the maintenance contract in October 2012 to PH Trams, a company established by Vitangcol's uncle-in-law. Vitangcol was also involved in an attempt to extort $30 million from Inekon Group in exchange of 48 train vehicles in July 2012.[200]

North Triangle Common Station

On November 21, 2013, the NEDA board, chaired by President Benigno Aquino III, approved the construction of a common station within North Avenue between SM City North EDSA and TriNoma Mall. It is estimated to cost 1.4 billion pesos. It will feature head-to-head platforms for LRT 1 and MRT 3 trains with a 147.4-meter (484 ft) elevated walkalator to MRT 7.[201] SM Investments Corporation posted 200 million pesos for the naming rights of the common station.[202] This is inconsistent with the original plan of having seamless connectivity to Monumento and is also an unusual arrangement of having two train stations beside each other. However, the project was shelved indefinitely due to disputes over cost, engineering issues and naming rights.[203] The Supreme Court halted the construction of the project in August 2014 after SM Prime Holdings contested the new location near Trinoma.[204][205] An agreement was later reached under the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte on September 28, 2016, and the common station finally begun construction on September 29, 2017.[206] Partial operations of the station will begin in 2023.[207]

Incidents

During the testing period of the system, the MRT–3 has been prone to numerous disruptions and breakdowns due to technical problems in the overall systems and design since its opening in 1999, due to many factors, such as the humid conditions in the country, lack of accessibility to the stations, and incompatible problems in the rolling stock, causing major adjustments to the system.

However, problems began to arise in 2012, due to poor maintenance causing train glitches, lack of spare parts, and negligence. The system has faced numerous interruptions and accidents. This in turn has caused lower ridership, frequent unloading of passengers and passenger inconvenience.[208]

These are some of the notable incidents involving the railway line:

- On November 3, 2012, a MRTC 3000 class train from the Araneta Center-Cubao Station caught fire as it approached GMA-Kamuning Station, causing passengers to scramble to the exits, and having two women injured. The train caught fire due to electrical short-circuit technical failure.[209]

- On March 26, 2014, a southbound MRTC 3000 class train at Guadalupe Station suddenly stopped due to the train driver not observing the red light status at the Guadalupe Station and accelerated southbound without getting prior clearance from the Control Center, causing the automatic train protection system to trigger and activate the emergency brakes, resulting in eight injuries.[210]

- On August 13, 2014, a southbound MRTC 3000 class train heading to Taft Avenue station derailed and overshot to the streets. The train first stopped after leaving Magallanes station due to a technical problem. Later on, the train broke down altogether, so another train was used to push the stalled train. During this process, however, the first train became detached from the rails and overshot towards Taft Avenue. As a result, the train crashed through the buffer stop and concrete barriers and derailed onto Taft Avenue. At least 38 people were injured. The accident was blamed on two train drivers and two control personnel for failing to follow the proper coordination procedures and protocol.[211][212]

- On September 2, 2014, a MRTC 3000 class train continued with one of its doors left open after a train door failed to close at the Guadalupe station. The passengers were then evacuated after the train arrived at Boni station.[213]

- On November 14, 2017, an alighting passenger at the Ayala station suddenly fell down to the tracks. The passenger was caught between the first and second cars of the train, and her arm was cut off. Operations were disrupted but was resumed shortly.[214] The injured passenger was then brought to a nearby hospital and her arm was reconnected by surgeons the following day.[215] Following this incident, the government reconsidered the use of platform screen doors in stations to prevent such incident.[94]

- On November 16, 2017, at 11:30 am, at least 140 passengers were evacuated from a train car that detached from a MRTC 3000 class train between the railway lines of Buendia and Ayala Avenue Stations.[216]

- On August 7, 2018, an aircon leak caused the inside of a MRTC 3000 class train to flood, prompting passengers inside to open their umbrellas. The train was removed from service to fix the air conditioning unit and the train involved in the incident returned to service the following day.[217]

- On September 26, 2018, two maintenance vehicles collided between Buendia and Guadalupe stations while doing a routine track maintenance, injuring 7 people. This resulted in a one-hour delay of the deployment of trains, causing long lines at stations.[218]

- On September 6, 2019, an overhead catenary line section snapped at Guadalupe Station, causing a power supply glitch in the whole line affecting over 7,000 passengers. Partial operations were implemented from North Avenue Station to Shaw Boulevard Station. The situation normalized at 5:00 pm.[219] The incident was caused by a defective and old Protection and Control Unit (PTU) that was overdue for replacement, after an investigation was made. Train preparation and daily maintenance were among the factors that failed to prevent this incident.[220]

- On November 4, 2019, at 4:08 pm, a MRTC 3000 class train suddenly emitted smoke while on the northbound track of the line. Around 530 passengers were unloaded. Around two hours after the incident, the operation of the line was back to normal.[221] The fire was caused by a short-circuit in the traction motor.[222]

- On May 9, 2021, two men were arrested for illegally going down to the railway tracks at Quezon Avenue station to take a selfie.[223]

- On May 12, 2021, a MRTC 3000 class train car was vandalized by an unidentified culprit near Taft Avenue station. Investigations were conducted and initial reports state that the culprit had cut the perimeter fence near Taft Avenue station, which may have caused the vandalism.[105]

- On October 9, 2021, a MRTC 3000 class train car caught fire near the Guadalupe station. A provisional service was implemented between North Avenue and Shaw Boulevard station, and the site of the incident was declared fire out at 9:51 pm. As a result of the incident, 8 passengers sustained minor injuries.[224] Normal operations resumed the following day.[225]

- On November 21, 2021, a window in a MRTC 3000 class LRV was damaged due to a stoning incident, with one injury reported.[226] The suspect was later identified as a garbage collector and was subsequently arrested and charged.[227]

- On June 12, 2022, two persons fell to their deaths from the EDSA-Taft Avenue (Tramo) flyover, onto the MRT-3 tracks leading to Taft Avenue station, causing an hour-long interruption in services.[228]

Notes

- The overhauls were carried out during most of the entire duration of the contract (originally 43 months) and not the initial 26-month rehabilitation period.

- Data from December 16 to 31, 1999.

- The LRT Line 1 first-generation trains originally came with forced ventilation until the trains were refurbished with air conditioning from 2003 to 2004.

References

- "About". Metro Rail Transit. Retrieved March 5, 2022.

- Sarao, Zacarian (January 5, 2023). "MRT-3 ridership breaches 98 million mark in 2022". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Retrieved January 5, 2023.

- Japan International Cooperation Agency; Oriental Consultants Co., Ltd.; ALMEC Corporation; Katahira & Engineers International; Tonichi Engineering Consultants, Inc. (July 2013). APPENDICES (PDF). STUDY ON RAILWAY STRATEGY FOR ENHANCEMENT OF RAILWAY NETWORK SYSTEM IN METRO MANILA OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES - FINAL REPORT - LRT LINE 1 CAVITE EXTENSION PROJECT (Report). Vol. 1. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- Pateña, Aerol John (February 9, 2018). "Bombardier to supply parts, signalling system for MRT upgrade anew". Philippine News Agency. Retrieved January 12, 2022.

- "Alstom in the Philippines" (PDF). Alstom. November 2021. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- Department of Transportation and Communications (2013). Design and/or Supply and Delivery of Forty-Eight (48) Light Rail Vehicles with On-board Communication System (Radio, Public Address, Intercom), On-board ATP System and One (1) Unit Train Simulator (PDF) (Report). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2021.

- "Govt eyes June for start of MRT-LRT loop project". BusinessWorld. April 18, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2022 – via GMA News.

- Salazar, Irineo B. R. (January 31, 2016). "On a clear day you can see the MRT". The Society of Honor by Joe America. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- Mendez, Christina (August 11, 2015). "Poe's Senate panel to resume hearing on Line 3". The Philippine STAR. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- Amojelar, Darwin G. (August 14, 2014). "DERAILED | 5 things you should know about MRT3 and the mess it's in". InterAksyon. TV5 News and Information. Archived from the original on August 16, 2014. Retrieved August 17, 2014.

- Padin, Mary Grace (November 8, 2018). "Government, inks P18.8 billion JICA loan for MRT-3 rehabilitation". The Philippine Star. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- Magsino, Dona (May 1, 2019). "MRT3 rehab, maintenance starts". GMA News Online. Retrieved June 16, 2021.

- Grecia, Leandre (March 22, 2022). "DOTr marks the completion of the MRT-3 Rehabilitation Project". Top Gear Philippines. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- Ombay, Giselle (December 9, 2021). "DOTr: Mitigating measures will be placed in case EDSA-North Avenue station temporarily closes". GMA News. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- Luna, Franco (March 29, 2022). "MRT-3 deploys 4-car, 3-car train sets simultaneously". The Philippine Star. Retrieved March 29, 2022.

- Valmonte, Kaycee; Luna, Franco (April 14, 2022). "Tugade sorry for inconvenience brought by MRT-3 closure on last workday of Holy Week". The Philippine Star. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

- "MRT, LRT-2 to suspend operations during Holy Week holidays". ABS-CBN News. March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 13, 2023.

- Grecia, Leandre (December 21, 2021). "Here are the LRT-1, LRT-2, MRT-3 schedules for Christmas 2021". Top Gear Philippines. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- Olchondra, Riza T. (May 29, 2009). "MRT-3 rides to go 24 hours starting June 1". Philippine Daily Inquirer. Archived from the original on May 30, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.