Modi script

Modi (Marathi: मोडी, Mōḍī, Marathi pronunciation: [moːɖiː])[3] is a script used to write the Marathi language, which is the primary language spoken in the state of Maharashtra, India. There are multiple theories concerning its origin.[4] The Modi script was used alongside the Devanagari script to write Marathi until the 20th century when the Balbodh style of the Devanagari script was promoted as the standard writing system for Marathi.[5]

| Mōḍī मोडी / 𑘦𑘻𑘚𑘲 | |

|---|---|

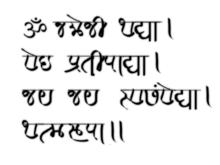

A verse from the Dnyaneshwari in the Mōḍī script | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 1200 or c. 1600–c. R1950[1][2] (Two different origin theories) |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | Primary Marathi Sometimes Konkani, Hindi, Gujarati, Kannada, Telugu and Sanskrit[1][2] |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Gujarati, Kaithi, Devanagari, Nandinagari |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Modi (324), Modi, Moḍī |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Modi |

| U+11600–U+1165F Final Accepted Script Proposal | |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

Etymology

The name "Modi" may be derived from the Marathi verb moḍaṇe (Marathi: मोडणे), which means "to bend or break". Modi is believed to be derived from broken Devanagari characters, which lends support to that particular etymology.[2]

It is not to be confused with the name Modi.

Origin theories

Hemāḍpant origin theory

Hemāḍpant was a minister during the reign of Mahadeva[6] (ruled 1261–1271) and the initial years of the reign of Rāmachandra (ruled 1271 to 1309)[7] of the Yadava Dynasty.[8][9][10]

Creation subtheory

Hemāḍpant created the Modi script.[9]

Refinement subtheory

The Modi script already existed in the 13th century; it was refined and introduced as an official script for Marathi by Hemāḍpant.[1]

History

There are various styles of the Modi script associated with a particular era. Many changes occurred in each era [2][6]

Proto-Modi

The proto-Modi, or ādyakālīn (आद्यकालीन) style appeared in the 12th century.

Yādav Era

The Yādav Era style, or yādavkālīn (यादव कालीन), emerged as a distinct style in the 13th century during the Yādav Dynasty.

Bahamanī Era

The Bahamanī Era style, or bahamanīkālīn (बहमनी कालीन), appeared in the 14th–16th centuries during the years of the Bahmani Sultanate.

Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Era

In Chatrapati Shiavji Maharaj Era, or shivakālīn (शिव कालीन), which was during the 17th century, the Chitnisi style of the Modi script developed.

Peshwa Era

In the Peshwa Era, or peshvekālīn (पेशवे कालीन), various Modi styles proliferated during the time of the Maratha Empire and lasted until 1818. The distinct styles of Modi used during this period were Chitnisi, Bilavalkari, Mahadevapanti, and Ranadi. Even though all of these were quite popular, Chitnisi was the most prominent and frequently used script for Modi writing.

British Colonial Era

The British colonial era, or the ānglakālīn (आंग्ल कालीन), was the final stage of the Modi script's development. It is associated with British rule and was used from 1818 to 1952. On 25 July 1917, the Bombay Presidency decided to replace the Modi script with the Balbodh style of Devnagari as the primary script of administration for the sake of convenience and uniformity with the other areas of the presidency. The Modi script continued to be taught in schools until several decades later and continued to be used as an alternate script to Balbodhi. The script was still widely used up until the 1940s by the people of older generations for personal and financial puropses.

Post-independence Era

The use of Modi has diminished since the independence of India. Now the Balbodh style of Devnagari is the primary script used to write Marathi.[11][12] However, some linguists in Pune have recently begun trying to revive the script.[13]

Description

Overview

The Modi script derives from the Nāgari family of scripts and is a modification of the Balbodh style of the Devanagari script intended for continuous writing. Although Modi is based upon Devanagari, it differs considerably from it in terms of letter forms, rendering behaviours, and orthography. The shapes of some consonants, vowels, and vowel signs are similar. The differences are visible in the behaviours of these characters in certain circumstances, such as consonant-vowel combinations and consonant conjuncts, which are standard features of Modi orthography. The Modi script has 46 distinctive letters, of which 36 are consonants and 10 vowels.[2]

Cursive features

The Modi script has several characteristics that facilitate writing, minimising having to lift the pen from the paper for dipping in ink while moving from one character to the next. Some characters are "broken" versions of their Devanagari counterparts, and many characters are more circular in shape. These characteristics make Modi a sort of cursive style of writing Marathi. The Modi script does not have the short 'i' (इ) and long 'ū' (ऊ) of Devanagari.[2] The cursive nature of the script also allowed scribes to easily make multiple copies of a document if required.[13]

Features of the letters

Numerous modifications are made to the Modi script in writing as "shortcuts", reflecting its history as a quasi-shorthand form of Devanagari.

The consonants fall into three broad categories: 1) Those that always retain their isolated form and attach their dependent vowel forms in a way common to most Indic scripts; 2) Those that take on a "contextual" form and change their form only in the presence of a dependent vowel immediately after, in which case those vowel forms are attached to the contextual form of the consonant in a uniform way as done with the consonants in Category 1 and with most other Indic alphabets; and 3) Those that form ligatures in the presence of vowel following the consonants. The ligatures are generally determined by the shape of the consonant and the presence of a loop on the right.

Regarding conjuncts, as in Devanagari, ksha and tra have special conjuncts, while other consonants typically occupy half forms or contextual forms. The letter ra is special, as it can take different visual positions as the first consonant in a conjunct cluster depending on whether it is palatalized or not. As the second consonant in a cluster, however, it functions almost identically as in Devanagari.

Alternative forms of the letter ra are also used to make multisyllabic clusters involving it. This is seen in kara, tara, sara, and a few others as a subjoined ra to the bottom right of a letter, and in joining at the end of other syllables, it is seen with a curved head. Following dependent vowel signs like -aa and punctuation marks like dandas, the ra also joins underneath, and any additional vowel marks are written directly on top of the subjoined ra.

Modi also has an empty circle that indicates abbreviations, which also may have been borrowed by Goykanadi, used for writing Konkani, which is closely related to Marathi.

Head stroke

The head stroke in Modi is unlike Devanagari in that it is typically written before the letters are, in order to produce a "ruled page" for writing Modi in lines. Thus, there are no word boundaries that can be visibly seen, since the head stroke does not break between words.

Usage

The Modi script was frequently used as a shorthand script for swift writing in business and administration. Modi was used primarily by administrative people as well as businessmen in keeping their accounts and writing Hundis (credit notes). Modi was also used to encrypt the message since not all people were well-versed in reading this script.[13]

Printing and typing

Printing

Before printing in Marathi was possible, the Modi script was used for writing prose and Balbodh was used for writing poetry. When printing in Marathi became possible, choosing between Modi and Balbodh was a problem. William Carey published the first book on Marathi grammar in 1805 using Balbodh since printing in the Modi script was not available to him in Serampore, Bengal. At the time Marathi books were generally written in Balbodh. However, subsequent editions of William Carey's book on Marathi grammar, starting in 1810, were written in the Modi script.[14][15] Using offset printing machines (previously Lithography) printing was in vogue.

Typing

Most Modi fonts are clip fonts. Some well-known Modi clip fonts include kotem1, developed by Ashok Kothare; Hemadree, developed by Somesh Bartakke; ModiGhate, developed by Sameer Ghate; and Modi Khilari, developed by Rajesh Khilari. Of these fonts, Hemadree and Modi Khilar' are the ones currently available.[16][17] Some other fonts for Modi use Devanagari Unicode Block to render Modi characters. The Modi script was included in Unicode for the first time in version 7.0.[2][18] This inclusion has recently led to the development of Unicode fonts for Modi, such as MarathiCursive and Noto Sans Modi. Also, a Unicode keyboard layout for Modi, named 'Modi (KaGaPa Phonetic)', has been recently added in the XKB keyboard stack,[19] which is mainly used in Linux based operating systems. The character mapping of this keyboard layout is similar to the existing Marathi (KaGaPa Phonetic) layout, but uses Modi's dedicated Unicode block for typing.

Documents in the Modi script

Most documents in Modi are handwritten. The oldest document in the Modi script is from 1389 and is preserved at the Bhārat Itihās Sanshodhan Mandal (BISM) in Pune.[6] The majority of documents and correspondence from before Shivaji Raje Bhonsle's times are written in the Modi script.[13]

Unicode

The Modi alphabet (U+11600–U+1165F) was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0.

| Modi[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1160x | 𑘀 | 𑘁 | 𑘂 | 𑘃 | 𑘄 | 𑘅 | 𑘆 | 𑘇 | 𑘈 | 𑘉 | 𑘊 | 𑘋 | 𑘌 | 𑘍 | 𑘎 | 𑘏 |

| U+1161x | 𑘐 | 𑘑 | 𑘒 | 𑘓 | 𑘔 | 𑘕 | 𑘖 | 𑘗 | 𑘘 | 𑘙 | 𑘚 | 𑘛 | 𑘜 | 𑘝 | 𑘞 | 𑘟 |

| U+1162x | 𑘠 | 𑘡 | 𑘢 | 𑘣 | 𑘤 | 𑘥 | 𑘦 | 𑘧 | 𑘨 | 𑘩 | 𑘪 | 𑘫 | 𑘬 | 𑘭 | 𑘮 | 𑘯 |

| U+1163x | 𑘰 | 𑘱 | 𑘲 | 𑘳 | 𑘴 | 𑘵 | 𑘶 | 𑘷 | 𑘸 | 𑘹 | 𑘺 | 𑘻 | 𑘼 | 𑘽 | 𑘾 | 𑘿 |

| U+1164x | 𑙀 | 𑙁 | 𑙂 | 𑙃 | 𑙄 | |||||||||||

| U+1165x | 𑙐 | 𑙑 | 𑙒 | 𑙓 | 𑙔 | 𑙕 | 𑙖 | 𑙗 | 𑙘 | 𑙙 | ||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Sample Text

Modi

𑘦𑘰𑘖𑘰 𑘦𑘨𑘰𑘙𑘲𑘓𑘲 𑘤𑘻𑘩𑘳 𑘎𑘼𑘝𑘳𑘎𑘹𑙁 𑘢𑘨𑘲 𑘀𑘦𑘿𑘨𑘲𑘝𑘰𑘝𑘹𑘮𑘲 𑘢𑘺𑘕𑘰𑘭𑘲 𑘕𑘲𑘽𑘎𑘹𑙁 𑘋𑘭𑘲 𑘀𑘎𑘿𑘬𑘨𑘹 𑘨𑘭𑘲𑘎𑘹𑙁 𑘦𑘹𑘯𑘪𑘲𑘡𑙂

Devanagari (Balbodh)

माझा मराठीची बोलू कौतुके। परि अमृतातेहि पैजासी जिंके। ऐसी अक्षरे रसिके। मेळवीन।।

-संत ज्ञानेश्वर

Roman (IAST)

mājhā marāṭhīcī bolū kautuke| pari amṛtātehi paijāsī jiṃke| aisī akṣare rasike| mel̤avīna||

-saṃta jñāneśvara

References

- Bhimraoji, Rajendra (28 February 2014). "Reviving the Modi Script" (PDF). Typoday. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 December 2014.

- Pandey, Anshuman (5 November 2011). "N4034: Proposal to Encode the Modi Script in ISO/IEC 10646" (PDF). ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2.

- Sahitya, Akademi (1992). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature Volume V. Sahitya Akademi New Delhi. p. 3898. ISBN 81-260-1221-8.

- "Krishnaji Mhatre – A life dedicated to Modi". Mumbai Mirror. 24 October 2017. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Sohoni, Pushkar (May 2017). "Marathi of a Single Type: The demise of the Modi script". Modern Asian Studies. 51 (3): 662–685. doi:10.1017/S0026749X15000542. ISSN 0026-749X. S2CID 148081127.

- Kulkarni, Sadanand A; Borde, Prashant L; Manza, Ramesh R; Yannawar, Pravin L (2014). "Offline Handwritten MODI Character Recognition Using HU, Zernike Moments and Zoning". arXiv:1406.6140 [cs.CV].

- Eternal Garden: Mysticism, History, and Politics at a South Asian Sufi Center by Carl W. Ernst p.107

- Mokashi, Digambar Balkrishna (1 July 1987). Palkhi: An Indian Pilgrimage. SUNY Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-88706-461-2.

- Mann, Gurinder Singh (1 March 2001). The Making of Sikh Scripture. Oxford University Press US. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-513024-3.

- "Modi Lipi Alphabets". September 2008. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013.

- Chhatrapati, Shahu; Sangave, Vilas Adinath; Khane, B. D. (1997). Rajarshi Shahu Chhatrapati papers. Vol. 7. Shahu Research Institute. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014.

- "History Of Modi Lipi". Modi Lipi. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013.

- "Band of researchers, enthusiasts strive to keep Modi script alive". The Times of India. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014.

- Rao, Goparaju Sambasiva (1994). Language Change: Lexical Diffusion and Literacy. Academic Foundation. pp. 48 and 49. ISBN 9788171880577. Archived from the original on 7 December 2014.

- Carey, William (1805). A Grammar of the Marathi Language. Serampore: Serampore Mission Press. ISBN 9781108056311.

- "other docs - Google site managed by Vishal Telangre". googlesite.vishaltelangre.com. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- "Download free MoDi Khilari 1 Regular font". www.dafontfree.net. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- BabelStone: What's new in Unicode 7.0

- "Added in(modi-kagapa) (93ea944c) · Commits · xkbdesc / xkeyboard-config". GitLab. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

External links

- MarathiCursiveG — free Modi Unicode font

- Modi at Omniglot

- Modi at Ancient Scripts

- Website about the Modi script