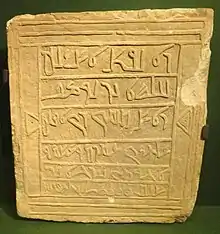

Nabataean script

The Nabataean script is an abjad (consonantal alphabet) that was used to write Nabataean Aramaic and Nabataean Arabic from the second century BC onwards.[2][3] Important inscriptions are found in Petra (now in Jordan), the Sinai Peninsula (now part of Egypt), and other archaeological sites including Abdah (in Israel) and Mada'in Saleh in Saudi Arabia.

| Nabataean script | |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | 2nd century BC to 4th century AD |

| Direction | right-to-left script |

| Languages | Nabataean Aramaic Nabataean Arabic |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Arabic script |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Nbat (159), Nabataean |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Nabataean |

| U+10880–U+108AF Final Accepted Script Proposal | |

Nabataean is only known through inscriptions and, more recently, a small number of papyri.[4] It was first deciphered in 1840 by Eduard Friedrich Ferdinand Beer.[4] 6,000 – 7,000 Nabataean inscriptions have been published, of which more than 95% are extremely short inscriptions or graffiti, and the vast majority are undated, post-Nabataean or from outside the core Nabataean territory.[4] A majority of inscriptions considered Nabataean were found in Sinai,[4] and another 4,000 – 7,000 such Sinaitic inscriptions remain unpublished.[5] Prior to the publication of Nabataean papyri, the only substantial corpus of detailed Nabataean text were the 38 funerary inscriptions from Hegra (Mada'in Salih), published by Julius Euting in 1885.[4]

History

The alphabet is descended from the Aramaic alphabet. In turn, a cursive form of Nabataean developed into the Arabic alphabet from the 4th century,[3] which is why Nabataean's letterforms are intermediate between the more northerly Semitic scripts (such as the Aramaic-derived Hebrew) and those of Arabic.

Comparison with related scripts

As compared to other Aramaic-derived scripts, Nabataean developed more loops and ligatures, likely to increase speed of writing. The ligatures seem to have not been standardized and varied across places and time. There were no spaces between words. Numerals in Nabataean script were built from characters of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 10, 20, and 100.

| Nabataean | Name | Arabic alphabet |

Syriac alphabet |

Hebrew alphabet |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ʾĀlap̄/ʾAlif | ا | ܐ | א | |

| Beth/Ba | ب | ܒ | ב | |

| Gamal/Jim | ج | ܓ | ג | |

| Dalath/Dal | ﺩ | ܕ | ד | |

| Heh | ه | ܗ | ה | |

| Waw | ﻭ | ܘ | ו | |

| Zain | ﺯ | ܙ | ז | |

| Ha/Heth | ح | ܚ | ח | |

| Teth | ط | ܛ | ט | |

| Yodh/Ya | ي | ܝ | י | |

| Kaph | ك | ܟ | כ | |

| Lamadh/Lam | ل | ܠ | ל | |

| Mim | م | ܡ | מ | |

| Nun | ن | ܢ | נ | |

| Simkath | ܣ | ס | ||

| 'E/Ain | ع | ܥ | ע | |

| Pe/Fa | ف | ܦ | פ | |

| Ṣāḏē/Ṣad | ص | ܨ | צ | |

| Qoph | ﻕ | ܩ | ק | |

| Resh/Ra | ﺭ | ܪ | ר | |

| Šin/Sin | س | ܫ | ש | |

| Taw/Ta | ﺕ | ܬ | ת |

- Note that the Syriac and Arabic alphabets are always cursive and that some of their letters look different in medial or initial position.

- See Aramaic alphabet § Letters for a more detailed comparison of letterforms.

Corpuses of inscriptions in Nabataean script

- Julius Euting, Nabatäische Inschriften aus Arabien, Berlin, 1885 (online).

- Euting, Julius (1891). Sinaïtische Inschriften (in German). G. Reimer. ISBN 978-3-11-108880-8.

- Corpus Inscriptionum Semiticarum, 1902 Pars 2, Tomus 1, Fasc 3: Inscriptiones Aramaicae

- Michael E. Stone, 1992. Rock Inscriptions and Graffiti Project: Catalogue of Inscriptions

- Roche, Marie-Jeanne (2019). Inscriptions nabatéennes datées de la fin du IIe siècle avant notre ère au milieu du IVe siècle (in French). Leuven. ISBN 978-90-429-3882-3. OCLC 1229107538.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

Petra inscriptions as of 1902

Petra inscriptions as of 1902 Sinai Peninsula inscriptions as of 1902

Sinai Peninsula inscriptions as of 1902 Wadi Mukattab inscriptions as of 1902

Wadi Mukattab inscriptions as of 1902

Unicode

The Nabataean alphabet (U+10880–U+108AF) was added to the Unicode Standard in June 2014 with the release of version 7.0.

| Nabataean[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1088x | 𐢀 | 𐢁 | 𐢂 | 𐢃 | 𐢄 | 𐢅 | 𐢆 | 𐢇 | 𐢈 | 𐢉 | 𐢊 | 𐢋 | 𐢌 | 𐢍 | 𐢎 | 𐢏 |

| U+1089x | 𐢐 | 𐢑 | 𐢒 | 𐢓 | 𐢔 | 𐢕 | 𐢖 | 𐢗 | 𐢘 | 𐢙 | 𐢚 | 𐢛 | 𐢜 | 𐢝 | 𐢞 | |

| U+108Ax | 𐢧 | 𐢨 | 𐢩 | 𐢪 | 𐢫 | 𐢬 | 𐢭 | 𐢮 | 𐢯 | |||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

References

- Himelfarb, Elizabeth J. "First Alphabet Found in Egypt", Archaeology 53, Issue 1 (Jan./Feb. 2000): 21.

- Everson, Michael (2010-12-09). "N3969: Proposal for encoding the Nabataean script in the SMP of the UCS" (PDF). Working Group Document, ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2.

- Omniglot.

- Healey, John F. (2011). "On Stone and Papyrus: reflections on Nabataean epigraphy". Palestine Exploration Quarterly. Informa UK Limited. 143 (3): 163–165. doi:10.1179/003103211x13092562976054. ISSN 0031-0328. S2CID 162206051.

Sinai, for example, is a major source of Nabataean inscriptions: the corpus of M. E. Stone contains 3,851 Nabataean items! But most were written by individuals who had no connection with Nabataea itself during the period of the Nabataean kingdom or its immediate aftermath and they may not normally have spoken Aramaic. The texts have generally been thought to have been written long after Nabataea as such disappeared.

- Larison, Kristine M. (2020). ""Prolific Writing": Retracing a Desert Palimpsest in the South Sinai". In A. Hoffmann (ed.). Exodus: Border Crossings in Jewish, Christian and Islamic Texts and Images. Judaism, Christianity, and Islam – Tension, Transmission, Transformation. De Gruyter. pp. 77–92. doi:10.1515/9783110618549-005. ISBN 978-3-11-061854-9. S2CID 214051677.

- Yaʻaḳov Meshorer, "Nabataean coins", Ahva Co-op Press, 1975; 114.

- https://en.numista.com/catalogue/pieces69784.html Numista