Psalm 127

Psalm 127 is the 127th psalm of the Book of Psalms, beginning in English in the King James Version: "Except the Lord build the house". In Latin, it is known by the incipit of its first 2 words, "Nisi Dominus".[1] It is one of 15 "Songs of Ascents" and the only one among them attributed to Solomon rather than David.

| Psalm 127 | |

|---|---|

| "Except the Lord build the house" | |

| Song of Ascents | |

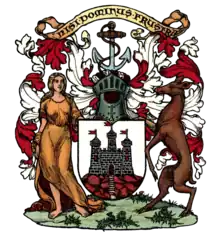

Arms of the city council of Edinburgh, with the Latin motto Nisi Dominus Frustra("Without the Lord, [all is] in vain") | |

| Other name |

|

| Language | Hebrew (original) |

In the slightly different numbering system used in the Greek Septuagint and the Latin Vulgate, this psalm is Psalm 126.

The text is divided into five verses. The first two express the notion that "without God, all is in vain", popularly summarized in Latin in the motto Nisi Dominus Frustra. The remaining three verses describe progeny as God's blessing.

The psalm forms a regular part of Jewish, Catholic, Lutheran, Anglican and other Protestant liturgies. The Vulgate text Nisi Dominus was set to music numerous times during the Renaissance and Baroque periods, often as part of vespers, including Claudio Monteverdi's ten-part setting as part of his 1610 Vespro della Beata Vergine, Marc-Antoine Charpentier, (3 sets), H 150, H 160, H 231, Handel's Nisi Dominus (1707) and two settings by Antonio Vivaldi. Composers such as Adam Gumpelzhaimer and Heinrich Schütz set the German "Wo Gott zum Haus".

Text

Hebrew Bible version

Following is the Hebrew text of Psalm 127:

| Verse | Hebrew |

|---|---|

| 1 | שִׁ֥יר הַֽמַּֽעֲל֗וֹת לִשְׁלֹ֫מֹ֥ה אִם־יְהֹוָ֚ה | לֹֽא־יִבְנֶ֬ה בַ֗יִת שָׁ֚וְא | עָֽמְל֣וּ בוֹנָ֣יו בּ֑וֹ אִם־יְהֹוָ֥ה לֹֽא־יִשְׁמָר־עִ֜֗יר שָׁ֚וְא | שָׁקַ֬ד שׁוֹמֵֽר |

| 2 | שָׁ֚וְא לָכֶ֨ם | מַשְׁכִּ֪ימֵי ק֡וּם מְאַֽחֲרֵי־שֶׁ֗בֶת אֹֽ֖כְלֵי לֶ֣חֶם הָֽעֲצָבִ֑ים כֵּ֚ן יִתֵּ֖ן לִֽידִיד֣וֹ שֵׁנָֽא |

| 3 | הִנֵּ֚ה נַֽחֲלַ֣ת יְהֹוָ֣ה בָּנִ֑ים שָֹ֜כָ֗ר פְּרִ֣י הַבָּֽטֶן |

| 4 | כְּחִצִּ֥ים בְּיַד־גִּבּ֑וֹר כֵּ֜֗ן בְּנֵ֣י הַנְּעוּרִֽים |

| 5 | אַשְׁרֵ֚י הַגֶּ֗בֶר אֲשֶׁ֚ר מִלֵּ֥א אֶת־אַשְׁפָּת֗וֹ מֵ֫הֶ֥ם לֹ֥א יֵבֹ֑שׁוּ כִּֽי־יְדַבְּר֖וּ אֶת־אֽוֹיְבִ֣ים בַּשָּֽׁעַר |

King James Version

- Except the LORD build the house, they labour in vain that build it: except the LORD keep the city, the watchman waketh but in vain.

- It is vain for you to rise up early, to sit up late, to eat the bread of sorrows: for so he giveth his beloved sleep.

- Lo, children are an heritage of the LORD: and the fruit of the womb is his reward.

- As arrows are in the hand of a mighty man; so are children of the youth.

- Happy is the man that hath his quiver full of them: they shall not be ashamed, but they shall speak with the enemies in the gate.

Authorship

According to Jewish tradition, Psalm 127 was written by David and dedicated to his son Solomon, who would build the First Temple.[2] According to Radak, verses 3–5, which reference "sons", express David's feelings about his son Solomon; according to Rashi, these verses refer to the students of a Torah scholar, who are called his "sons".[2]

The psalm's superscription calls it "of Solomon",[3] but Christian theologian Albert Barnes noted that "in the Syriac Version, the title is, "From the Psalms of the Ascent; spoken by David concerning Solomon; it was spoken also of Haggai and Zechariah, who urged the rebuilding of the Temple".[4] The Authorized Version describes the psalm as "a Song of degrees for Solomon",[5] and Wycliffe's translators recognised both options.[6] Isaac Gottlieb of Bar Ilan University suggests that the reference in verse 2 to "his beloved" (yedido) "recalls Solomon's other name, Yedidiah".[7]

Themes

Charles Spurgeon calls Psalm 127 "The Builder's Psalm", noting the similarity between the Hebrew words for sons (banim) and builders (bonim). He writes:

We are here taught that builders of houses and cities, systems and fortunes, empires and churches all labour in vain without the Lord; but under the divine favour they enjoy perfect rest. Sons, who are in the Hebrew called "builders", are set forth as building up families under the same divine blessing, to the great honour and happiness of their parents.[8]

Spurgeon also quotes the English preacher Henry Smith (1560–1591): "Well doth David call children 'arrows' [v. 4]; for if they be well bred, they shoot at their parents' enemies; and if they be evil bred, they shoot at their parents".[8]

The Midrash Tehillim interprets the opening verses of the psalm as referring to teachers and students of Torah. On the watchmen of the city mentioned in verse 1, Rabbi Hiyya, Rabbi Yosi, and Rabbi Ammi said, "The [true] watchmen of the city are the teachers of Scripture and instructors of Oral Law". On "the Lord gives" in verse 2, the Midrash explains that God "gives" life in the world to come to the wives of Torah scholars because they deprive themselves of sleep to support their husbands.[9]

Translation

The translation of the psalm offers difficulties, especially in verses 2 and 4. Jerome, in a letter to Marcella (dated 384 AD), laments that Origen's notes on this psalm were no longer extant, and discusses the various possible translations of לֶחֶם הָעֲצָבִים (KJV "bread of sorrows", after the panem doloris of Vulgata Clementina; Jerome's own translation was panem idolorum, "bread of idols", following the Septuagint (LXX), and of בְּנֵי הַנְּעוּרִֽים (KJV "children of the youth", translated in LXX as υἱοὶ τῶν ἐκτετιναγμένων "children of the outcast").[10]

There are two possible interpretations of the phrase כֵּן יִתֵּן לִֽידִידֹו שֵׁנָֽא (KJV: "for so he giveth his beloved sleep"): The word "sleep" may either be the direct object (as in KJV, following LXX and Vulgate), or an accusative used adverbially, "in sleep", i.e. "while they are asleep". The latter interpretation fits the context of the verse much better, contrasting the "beloved of the Lord" who receive success without effort, as it were "while they sleep" with the sorrowful and fruitless toil of those not so blessed, a sentiment paralleled by Proverbs 10:22 (KJV "The blessing of the LORD, it maketh rich, and he addeth no sorrow with it."). Keil and Delitzsch (1883) accept the reading of the accusative as adverbial, paraphrasing "God gives to His beloved in sleep, i.e., without restless self-activity, in a state of self-forgetful renunciation, and modest, calm surrender to Him".[11]

However, Alexander Kirkpatrick in the Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges (1906) argues that while the reading "So he giveth unto his beloved in sleep" fits the context, the natural translation of the Hebrew text is still the one given by the ancient translators, suggesting that the Hebrew text as transmitted has been corrupted (which would make the LXX and Vulgate readings not so much "mistranslations" as correct translations of an already corrupted reading).[12]

English translations have been reluctant to emend the translation, due to the long-standing association of this verse with sleep being the gift of God.[13] Abraham Cronbach (1933) refers to this as "one of those glorious mistranslations, a mistranslation which enabled Mrs. Browning to write one of the tenderest poems in the English language",[14] referring to Elizabeth Barrett Browning's poem The Sleep, which uses "He giveth his beloved Sleep" as the last line of each stanza.

Keil and Delitzsch (1883) take שֶׁבֶת, "to sit up", as confirmation for the assumption, also suggested by 1 Samuel 20:24, that the custom of the Hebrews before the Hellenistic period was to take their meals sitting up, and not reclining as was the Greco-Roman custom.[15]

Uses

Judaism

In Judaism, Psalm 127 is recited as part of the series of psalms read after the Shabbat afternoon service between Sukkot and Shabbat HaGadol.[16]

It is also recited as a prayer for protection of a newborn infant.[17]

Catholic Church

Since the early Middle ages, this psalm was traditionally recited or sung at the Office of None during the week, specifically from Tuesday until Saturday between Psalm 126 and Psalm 128, following the Rule of St. Benedict.[18] During the Liturgy of the Hours, Psalm 126 is recited at vespers on the third Wednesday of the four weekly liturgical cycle.

Protestantism

The pro-natalist Quiverfull movement invokes the less quoted latter part of the psalm, verses 3–5 concerning the blessings and advantages of numerous offspring, as one of the foundations for their stance and takes its name from the last verse ("Happy is the man that hath his quiver full of them [i.e. sons]").[19]

Musical settings

In Latin

The Vulgate text of the psalm, Nisi Dominus, has been set to music many times, often as part of vespers services. Settings from the classical period use the text of the Sixto-Clementine Vulgate of 1592, which groups Cum dederit dilectis suis somnum ("as he gives sleep to those in whom he delights") with verse 3 rather than verse 2 (as opposed to Jerome's text, and most modern translations, grouping the phrase with verse 2). Notable compositions include:[20]

- Orlando di Lasso, a capella motet for five voices, (published in 1562).[21]

- Hans Leo Hassler, a capella motet, published in Cantiones sacrae, 1591.

- Giovanni Matteo Asola, a capella setting published in 1599.

- Monteverdi's "Nisi Dominus" for a ten-part choir, part of Vespro della Beata Vergine (1610).

- Alessandro Grandi, motet with trombones and basso continuo, published in 1630

- Francesco Cavalli, setting for four parts and strings, published in Musiche Sacre Concernenti, Venice, (1656).

- Giovanni Giacomo Arrigoni, motet "Nisi Dominus", published in 1663

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier :

- "Nisi Dominus", grand motet for soloists, chorus, 2 treble instruments and continuo H.150 (? early 1670).

- "Nisi Dominus", grand motet for soloists, chorus and continuo H.160 - 160 a (? early 1670).

- "Nisi Dominus", motet for 3 voices, 2 treble instruments and continuo H.231 (date unknown).

- Biber, cantata for 2 voices, violin and b.c. (after 1676).

- Handel's "Nisi Dominus", believed to have been written for a vespers service in 1707

- Henry Desmarest, grand motet "Nisi Dominus" (17..).

- Jan Dismas Zelenka, motet "Nisi Dominus" ZWV 92, c. 1726.

- Michel-Richard Delalande, grand motet "Nisi Dominus" S42 (1729).

- Jean-Joseph Cassanéa de Mondonville, grand motet "Nisi Dominus aedificavit" (1743).

- Antonio Vivaldi, two settings, RV 608 for strings and solo voice, and RV 803 for strings and choir, discovered among the "Galuppi" sacred works in the Saxon State and University Library Dresden in 2006.[22]

In German

"Wo Gott zum Haus" is a German metrical and rhyming paraphrase of the psalm by Johann Kolross, set to music by Luther (printed 1597) and by Hans Leo Hassler (c. 1607). Adam Gumpelzhaimer used the first two lines for a canon, Wo Gott zum Haus nicht gibt sein Gunst / So arbeit jedermann umsonst ("Where God to the house does not give his blessing / There toils every man in vain"). Heinrich Schütz composed a metred paraphrase of the psalm, "Wo Gott zum Haus nicht gibt sein Gunst", SWV 232, for the Becker Psalter, published first in 1628; He set Wo der Herr nicht das Haus bauet, SWV 400, in 1650.

In English

- Florence Margaret Spencer Palmer (1900-1987) motet "Except the Lord Build the House"[23]

Nisi Dominus Frustra

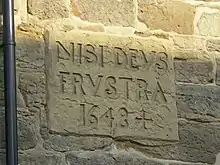

Nisi Dominus Frustra ("Without God, [it is] in vain") is a popular motto derived from the psalm's first verse, as an abbreviation of "Except the Lord build the house, they labour in vain that build it". It is often inscribed on buildings. It has been the motto in the coat of arms of the City of Edinburgh since 1647,[24] and was the motto of the former Metropolitan Borough of Chelsea.[25] It was similarly the motto of the King's Own Scottish Borderers,[24] and the motto of the Inglises of Cramond[26] shared with Bishop Charles Inglis and his descendants.

It has been adopted as the motto for numerous schools in Great Britain, including King Edward VI High School, Stafford,[27] Melbourn Village College, London,[28] and as the insignia of Glenlola Collegiate School in Northern Ireland.[29] Other schools with this motto are St Joseph's College, Dumfries, Villa Maria Academy (Malvern, Pennsylvania), Rickmansworth School (Nisi Dominus Aedificaverit), The Park School, Yeovil, Bukit Bintang Girls' School, Bukit Bintang Boys' Secondary School, St Thomas School, Kolkata, Kirkbie Kendal School, Richmond College, Galle, Mount Temple Comprehensive School, Dublin, Ireland, Durban Girls' College, Durban, South Africa, and Launceston Church Grammar School, Tasmania, Australia.[30]

The Aquitanian city of Agen takes as its motto the second verse of the psalm, "Nisi dominus custodierit civitatem frustra vigilat qui custodit eam": "Unless the Lord watches over the city, the guards stand watch in vain" (verse 1a, NIV version).

Edinburgh Napier University, established in 1964, has "secularized" the city's motto to "Nisi sapientia frustra" ("without knowledge/wisdom, all is in vain").

References

- Parallel Latin/English Psalter / Psalmus 126 (127) medievalist.net

- Abramowitz, Rabbi Jack (2019). "Sing a Song of Solomon". Orthodox Union. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- See for example Psalm 127:1 in the New International Version

- Barnes, Albert (1834). "Psalm 127: Barnes' Notes". Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- Psalms 127

- Noble, T. P. (2001), Psalm 127:1

- Gottlieb, Isaac B. (2010). "Mashal Le-Melekh: the Search for Solomon". Hebrew Studies. 51: 107–127. JSTOR 27913966.

- Spurgeon, Charles H. (2019). "Psalm 127 Bible Commentary". Christianity.com. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "Midrash Tehillim / Psalms 127" (PDF). matsati.com. October 2012. Retrieved February 28, 2019. (password: www.matsati.com)

- Ph. Schaff, H. Wace, The Principal Works of St. Jerome (1892), Letter xxxiv. To Marcella "The Hebrew phrase 'bread of sorrow' is rendered by the LXX. 'bread of idols'; by Aquila, 'bread of troubles'; by Symmachus, 'bread of misery'. Theodotion follows the LXX. So does Origen's Fifth Version. The Sixth renders 'bread of error.' In support of the LXX, the word used here is in Ps. cxv.4, translated 'idols.' Either the troubles of life are meant or else the tenets of heresy."

- "God gives to His beloved (Psalm 60:7; Deuteronomy 33:12) שׁנא (equals שׁנה), in sleep (an adverbial accusative like לילה בּּקר, ערב), i.e., without restless self-activity, in a state of self-forgetful renunciation, and modest, calm surrender to Him: 'God bestows His gifts during the night,' says a German proverb, and a Greek proverb even says: εὕδοντι κύρτος αἱρεῖ [the fish-trap catches while they sleep]. Bücher takes כּן in the sense of 'so equals without anything further', and כן certainly has this mean,ing sometimes (vid., introduction to Psalm 110:1-7), but not in this passage, where, as referring back, it stands at the head of the clause, and where what this mimic כן would import lies in the word שׁנא." Carl Friedrich Keil, Franz Delitzsch Commentary on the Old Testament (Biblischer Kommentar über das Alte Testament vol. 8, 1883), English edition by T. and T. Clark, Edinburgh (1892–94).

- "Most commentators however adopt the rendering, So he giveth unto his beloved in sleep. This rendering is certainly not the natural rendering of the Heb. text. Wellhausen condemns it as "quite inadmissible". It requires the supplement of an object to the verb, and שֵׁנָא must be taken as accus. of manner. If it were not for the exegetical difficulty, no one would hesitate to take 'sleep,' as the Ancient Versions take it, as the object of the verb 'giveth.' Some word however seems to be needed to correspond to the results of anxious toil, and though the Ancient Versions already had the present reading, the text may be corrupt. The anomalous form of the word for sleep (שנא for שנה) may point in this direction."

- Charles Ellicott, Commentary for English Readers (1897). Modern translations which do emend the passage include Brenton (1844), New American Standard Bible (1968), Complete Jewish Bible (1998), New English Translation (2005); Luther (1545) already has "denn seinen Freunden gibt er's schlafend" ("as to his friends he grants while [they are] asleep").

- Abraham Cronbach, Religion and Its Social Setting: Together with Other Essays (1933), p. 193.

- Carl Friedrich Keil, Franz Delitzsch Commentary on the Old Testament (Biblischer Kommentar über das Alte Testament vol. 8, 1883), English edition by T. and T. Clark, Edinburgh (1892–94).

- Scherman 2003, pp. 530, 538.

- "Protection". Daily Tehillim. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- Prosper Guéranger, Règle de saint Benoît, (Abbaye Saint-Pierre de Solesmes, réimpression 2007) p46.

- Kaufmann, Eric (2010). Shall the religious inherit the Earth? : demography and politics in the twenty-first century (2nd print. ed.). London: Profile Books. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-84668-144-8.

- See Psalm 127 at Choral Public Domain Library for a detailed list.

- Sacrae cantiones quinque vocum, Nuremberg, 1562), no. 15. Lasso's version predates the Vulgata Clementina, but his text already follows its reading Cum dederit dilectis suis somnum, ecce hæreditas Domini filii, merces fructus ventris. which is derived from revised editions of the Vulgate published in the first half of the 16th century, notably those by Stephanus.

- Stockigt, Janice B.; Talbot, Michael (March 2006). "Two More New Vivaldi Finds in Dresden". Eighteenth Century Music. 3 (1): 35–61. doi:10.1017/S1478570606000480.

- Evans, Robert; Humphreys, Maggie (1997-01-01). Dictionary of Composers for the Church in Great Britain and Ireland. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4411-3796-8.

- "Edinburgh's motto". The Scotsman. 9 December 2009. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "Book-plate for Chelsea Public Library, 1903". British Museum. 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "Connections with other Inglis families".

- "King Edward VI: A History". King Edward VI High School. 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- Beard, Mary (16 September 2011). "Nisi dominus frustra: Why ditch a motto?". The Times Literary Supplement. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "School History". Glenlola Collegiate School. Retrieved 28 February 2019.

- "Launceston Church Grammar School". Launceston Church Grammar School. Retrieved 2022-06-02.

Sources

- Scherman, Rabbi Nosson (2003). The Complete Artscroll Siddur (3rd ed.). Mesorah Publications. ISBN 9780899066509.

External links

- Pieces with text from Psalm 127: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Psalm 127: Free scores at the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Text of Psalm 127 according to the 1928 Psalter

- Psalms Chapter 127 text in Hebrew and English, mechon-mamre.org

- Unless the LORD build the house, they labor in vain who build. text and footnotes, usccb.org United States Conference of Catholic Bishops

- Psalm 127:1 introduction and text, biblestudytools.com

- Psalm 127 – God’s Work in Building Houses, Cities, and Families enduringword.com

- Psalm 127 / Refrain: The Lord shall keep watch over your going out and your coming in. Church of England

- Psalm 127 at biblegateway.com