Struthiomimus

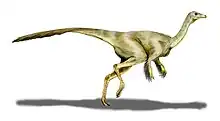

Struthiomimus, meaning "ostrich-mimic" (from the Greek στρούθειος/stroutheios, or "of the ostrich", and μῖμος/mimos, meaning "mimic" or "imitator"), is a genus of ornithomimid dinosaurs from the late Cretaceous of North America. Ornithomimids were long-legged, bipedal, ostrich-like dinosaurs with toothless beaks. The type species, Struthiomimus altus, is one of the more common, smaller dinosaurs found in Dinosaur Provincial Park; their overall abundance—in addition to their toothless beak—suggests that these animals were mainly herbivorous or (more likely) omnivorous, rather than purely carnivorous, if at all. Similar to the modern extant ostriches, emus, and rheas (among other birds), ornithomimid dinosaurs likely lived as opportunistic omnivores, supplementing a largely plant-based diet with a variety of small mammals, reptiles, amphibians, insects, invertebrates, and anything else they could fit into their mouth, as they foraged.[1]

| Struthiomimus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous, | |

|---|---|

| |

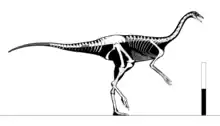

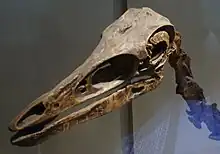

| Cast of an S. altus skeleton, Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | †Ornithomimosauria |

| Family: | †Ornithomimidae |

| Genus: | †Struthiomimus Osborn, 1917 |

| Species: | †S. altus |

| Binomial name | |

| †Struthiomimus altus (Lambe, 1902) | |

History of discovery

In 1901, Lawrence Lambe found some incomplete remains, holotype CMN 930, and named them Ornithomimus altus, placing them in the same genus as material earlier described by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1890. The specific name altus is from Latin, meaning "lofty" or "noble". However, in 1914, a nearly complete skeleton (AMNH 5339) was discovered by Barnum Brown at the Red Deer River site in Alberta, prompting O. altus to be described as the type genus of a new subgenus, Struthiomimus, by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1917.[2] Dale Russell made Struthiomimus a full genus in 1972, at the same time referring several other specimens to it: AMNH 5375, AMNH 5385, AMNH 5421, CMN 8897, CMN 8902 and ROM 1790, all partial skeletons.[3] The type species, S. altus, is known from several skeletons and skulls,[4] In 1916 Osborn also renamed Ornithomimus tenuis Marsh 1890 into Struthiomimus tenuis.[2] This is today considered a nomen dubium. In 2016, ROM 1790 was made the holotype of a new genus and species, Rativates evadens.[5]

In subsequent years William Arthur Parks named four other species of Struthiomimus: Struthiomimus brevetertius Parks 1926,[6] Struthiomimus samueli Parks 1928,[7] Struthiomimus currellii Parks 1933 and Struthiomimus ingens Parks 1933.[8] These are today seen as either belonging to Dromiceiomimus or to Ornithomimus.

In 1997 Donald Glut mentioned the name Struthiomimus lonzeensis.[9] This was probably a lapsus calami, a mistake for Ornithomimus lonzeensis (Dollo 1903) Kuhn 1965. Struthiomimus altus comes from the Late Campanian (Judithian age) Oldman Formation.[10]

A possible second species of Struthiomimus is known from the early Maastrichtian (Edmontonian age) Horseshoe Canyon Formation. Because dinosaur fauna show rapid turnover, it is likely that these younger Struthiomimus specimens represent a species distinct from S. altus, though no new name has been given to them.[10][11]

Additional Struthiomimus specimens from the lower Lance Formation and equivalents are larger (similar to Gallimimus in size) and tend to have straighter and more elongate hand claws, similar to those seen in Ornithomimus. One relatively complete Lance Formation specimen, BHI 1266, was originally referred to Ornithomimus sedens (named by Marsh in 1892[12]) and later classified as Struthiomimus sedens.[13] One 2015 paper by van der Reest et al. listed BHI 1266 as Ornithomimus sp.,[14] while another paper the same year considered the specimen Struthiomimus sp. pending a re-evaluation of both genera.[10]

Description

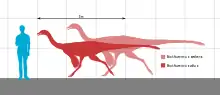

The size of S. altus is estimated as about 4.3 metres (14 ft 1 in) long and 1.4 m (4 ft 7 in) tall at the hips, with a weight of around 150 kilograms (330 lb).[15] A larger specimen of S. altus is estimated to weigh about 233.8 kilograms (515 lb).[16] The specimens belonging to "S." sedens measured 4.8 metres (16 ft) long and weighed 350 kilograms (770 lb).[17] Struthiomimus had a build and skeletal structure typical of ornithomimids, differing from closely related genera like Ornithomimus and Gallimimus in proportions and anatomical details.[18]

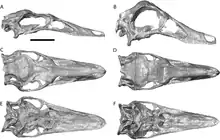

As with other ornithomimids, they had small slender heads on long necks (which made up about 40% of the length of the body in front of the hips).[4] Their eyes were large and their jaws were toothless. Their vertebral columns consisted of ten neck vertebrae, thirteen back vertebrae, six hip vertebrae, and about thirty-five tail vertebrae.[19] Their tails were relatively stiff and probably used for balance.[2] They had long slender arms and hands, with immobile forearm bones and limited opposability between the first finger and the other two.[20] As in other ornithomimids but unusually among theropods, the three fingers were roughly the same length, and the claws were only slightly curved; Henry Fairfield Osborn, describing a skeleton of S. altus in 1917, compared the arm to that of a sloth.[2] These might have been adaptations to support wing feathers.[21] It is likely it had feathers all over its body. Struthiomimus differed from close relatives only in subtle aspects of anatomy. The edge of the upper beak was concave in Struthiomimus, unlike Ornithomimus, which had straight beak edges.[11] Struthiomimus had longer hands relative to the humerus than other ornithomimids, with particularly long claws.[4] Their forelimbs were more robust than Ornithomimus.[11]

Classification

Struthiomimus is a member of the family Ornithomimidae, a group which also includes Anserimimus, Archaeornithomimus, Dromiceiomimus, Gallimimus, Ornithomimus, and Sinornithomimus.

Just as the fossil remains of Struthiomimus were incorrectly assigned to Ornithomimus, the larger group that Struthiomimus belongs to, the Ornithomimosauria, also underwent many changes over the years. For example, O.C. Marsh initially included Struthiomimus in the Ornithopoda, a large clade of dinosaurs not closely related to theropods.[22] Five years later, Marsh classified Struthiomimus in the Ceratosauria.[23][24] In 1891, Baur placed the genus within Iguanodontia.[25] As late as 1993, Struthiomimus was referred to Oviraptorosauria.[26] However, by the 1990s, there were numerous studies that placed Struthiomimus within Coelurosauria.[27][28][29][30]

Recognizing the difference between ornithomimids and other theropods, Rinchen Barsbold placed ornithomimids within their own infraorder, Ornithomimosauria, in 1976.[31] The constituency of Ornithomimidae and Ornithomimosauria varied with different authors. Paul Sereno, for example, used Ornithomimidae to include all ornithomimosaurians in 1998, but subsequently changed to a more exclusive definition (advanced ornithomimosaurs) within Ornithomimosauria,[32] a classification scheme that was adopted by other authors at the beginning of the current century.

The cladogram follows the 2011 analysis by Xu et al.:[33]

| Ornithomimidae |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

In a 2001 study conducted by Bruce Rothschild and other paleontologists, fifty foot bones referred to Struthiomimus were examined for signs of stress fracture, but none were found.[34]

Struthiomimus was one of the first theropods envisioned from the outset as having a horizontal posture. Osborn in 1916 let the animal intentionally be depicted with an elevated tail.[2] This newer view created an image much more reminiscent of modern flightless birds, such as the ostrich to which this dinosaur's name refers, but would only much later be accepted for all theropods.

Diet

There has been much discussion about the feeding habits of Struthiomimus. Because of its straight-edged beak, Struthiomimus may have been an omnivore. Some theories suggest that it may have been a shore-dweller and may have been a filter feeder.[19] Some paleontologists noted that it was more likely to be a carnivore because it is classified within the otherwise carnivorous theropod group.[3][35] This theory has never been discounted, but Osborn, who described and named the dinosaur, proposed that it probably ate buds and shoots from trees, shrubs and other plants,[18] using its forelimbs to grasp branches and its long neck to enable it accurately to select particular items. This herbivorous diet is further supported by the unusual structure of its hands. The second and third fingers were of equal length, could not function independently, and were probably bound together by skin as a single unit. The structure of the shoulder girdle did not allow a high elevation of the arm nor was optimised for a low reach. The hand could not be fully flexed for a grasping motion or spread for raking. This indicates that the hand was used as a "hook" or "clamp", for bringing branches or fern fronds at shoulder height within reach.[20] However, these adaptations might have been used for wing feather support instead.[21]

Speed

The legs (hind limbs) of Struthiomimus were long, powerful and seemingly well-suited to rapid running, much like an ostrich. The supposed speed of Struthiomimus was, in fact, its main defense from predators (although it may also have been able to lash out with its hind claws when cornered), such as the dromaeosaurids (e.g. Saurornitholestes and Dromaeosaurus) and tyrannosaurs (e.g. Daspletosaurus and Gorgosaurus), which lived at the same time. It is estimated to have been able to run at speeds between 50 and 80 km/h (31.1 and 49.7 mph).[36]

Paleoecology

Fossil remains of S. altus are only known definitively from the Oldman Formation, dated to between 78 and 77 million years ago during the Campanian stage of the late Cretaceous period.[10] A younger species (which has not yet been named), which apparently differed from S. altus in having longer, more slender hands, is known from several specimens found in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation and lower Lance Formation, between 69 and 67.5 million years ago (early Maastrichtian).[10]

See also

References

- Barrett, Paul M (2005). "The diet of ostrich dinosaurs (Theropoda: Ornithomimosauria)". Palaeontology. 48 (2): 347–358. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2005.00448.x.

- Osborn, Henry Fairfield (1917). "Skeletal adaptations of Ornitholestes, Struthiomimus, Tyrannosaurus" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 35: 733–771.

- Russell D (1972). "Ostrich dinosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of Western Canada". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 9 (4): 375–402. Bibcode:1972CaJES...9..375R. doi:10.1139/e72-031.

- Currie, Philip J. (2005). "Theropods, Including Birds". In Currie, Phillip J.; Koppelhus, Eva (eds.). Dinosaur Provincial Park: A Spectacular Ancient Ecosystem Revealed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 367–397. ISBN 978-0-253-34595-0.

- McFeeters, Bradley; Ryan, Michael J.; Schröder-Adams, Claudia; Cullen, Thomas M. (2016). "A new ornithomimid theropod from the Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36 (6): e1221415. doi:10.1080/02724634.2016.1221415. S2CID 89242374.

- Parks, W.A. (1926). "Struthiomimus brevetertius - A new species of dinosaur from the Edmonton Formation of Alberta". Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. Series 3. 20 (4): 65–70.

- Parks, W.A. (1928). "Struthiomimus samueli, a new species of Ornithomimidae from the Belly River Formation of Alberta". University of Toronto Studies, Geology Series. 26: 1–24.

- Parks, W.A. (1933). "New species of dinosaurs and turtles from the Upper Cretaceous formations of Alberta". University of Toronto Studies, Geological Series. 34: 1–33.

- Glut, D., 1997, Dinosaurs - The Encyclopedia. McFarland Press, Jefferson, NC. 1076 pp

- Claessens, L.; Loewen, Mark A. (2015). "A redescription of Ornithomimus velox Marsh, 1890 (Dinosauria, Theropoda)". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 36: e1034593. doi:10.1080/02724634.2015.1034593. S2CID 85861590.

- Longrich, N (2008). "A new, large ornithomimid from the Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation of Alberta, Canada: Implications for the study of dissociated dinosaur remains". Palaeontology. 51 (4): 983–997. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2008.00791.x.

- Marsh, O.C. (1892). "Notice of new reptiles from the Laramie Formation". American Journal of Science. Series 3. 43 (257): 449–453. Bibcode:1892AmJS...43..449M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-43.257.449. S2CID 131291138.

- Farlow, J.O., 2001, "Acrocanthosaurus and the maker of Comanchean large-theropod footprints", In: Tanke, Carpenter, Skrepnick and Currie (eds). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life: New Research Inspired by the Paleontology of Philip J. Currie. pp. 408-427

- Aaron, J.; van der Reest, Alexander P. Wolfe; Currie, Philip J. (2016). "[2015] A densely feathered ornithomimid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Upper Cretaceous Dinosaur Park Formation, Alberta, Canada". Cretaceous Research. 58: 108–117. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.10.004.

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988). "Ornithomimus altus". Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 387–389. ISBN 978-0-671-61946-6.

- Chinzorig, Tsogtbaatar; Cullen, Thomas; Phillips, George; Rolke, Richard; Zanno, Lindsay E. (2022-10-19). "Large-bodied ornithomimosaurs inhabited Appalachia during the Late Cretaceous of North America". PLOS One. 17 (10). e0266648. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0266648.

- Paul, Gregory S. (2010). The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988). "Genus Ornithomimus". Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 384–394. ISBN 978-0-671-61946-6.

- Makovicky, Peter J.; Kobayashi, Yoshitsugu; Currie, Philip J. (2004). "Ornithomimosauria". In Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 137–150. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- Nicholls, Elizabeth L.; Russell, Anthony P. (1985). "Structure and function of the pectoral girdle and forelimb of Struthiomimus altus (Theropoda: Ornithomimidae)". Palaeontology. 28: 643–677.

- Zelenitsky, D. K.; Therrien, F.; Erickson, G. M.; Debuhr, C. L.; Kobayashi, Y.; Eberth, D. A.; Hadfield, F. (2012). "Feathered Non-Avian Dinosaurs from North America Provide Insight into Wing Origins". Science. 338 (6106): 510–514. Bibcode:2012Sci...338..510Z. doi:10.1126/science.1225376. PMID 23112330. S2CID 2057698.

- Marsh, O. C. (1890). "Additional characters of the Ceratopsidae, with notice of new Cretaceous dinosaurs". American Journal of Science. 39 (233): 418–426. Bibcode:1890AmJS...39..418M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-39.233.418. S2CID 130812960.

- Marsh, O. C. (1895). "On the affinities and classification of the dinosaurian reptiles". American Journal of Science. 50 (300): 483–498. Bibcode:1895AmJS...50..483M. doi:10.2475/ajs.s3-50.300.483. S2CID 130517438.

- O. C. Marsh. 1896. The dinosaurs of North America. United States Geological Survey, 16th Annual Report, 1894-95 55:133-244

- Baur, G. (1891). "Remarks on the reptiles generally called Dinosauria". The American Naturalist. 25 (293): 434–454. doi:10.1086/275329. S2CID 84575190.

- Russell, D. A.; Dong, Z.-M. (1993). "The affinities of a new Theropod from the Alxa Desert, Inner Mongolia, People's Republic of China". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 30 (10–11): 2107–2127. Bibcode:1993CaJES..30.2107R. doi:10.1139/e93-183.

- J. A. Gauthier and K. Padian. 1985. Phylogenetic, functional, and aerodynamic analyses of the origin of birds and their flight. In M. K. Hecht, J. H. Ostrom, G. Viohl, and P. Wellnhofer (eds.), The Beginnings of Birds: Proceedings of the International Conference Archaeopteryx, Eichstätt 1984. Freunde des Jura-Museums Eichstätt, Eichstätt 185-197

- F. E. Novas. 1992. The evolution of carnivorous dinosaurs. In J. L. Sanz and A. D. Buscalioni (eds.), The Dinosaurs and Their Environment Biotic: Proceedings of the Second Year of Paleontology in Cuenca. Institute "Juan Valdez", Cuenca, Argentina 126-163

- Sereno, P. C.; Wilson, J. A.; Larsson, H. C. E.; Dutheil, D. B.; Sues, H.-D. (1994). "Early Cretaceous dinosaurs from the Sahara". Science. 266 (5183): 267–271. Bibcode:1994Sci...266..267S. doi:10.1126/science.266.5183.267. PMID 17771449. S2CID 36090994.

- Makovicky, P. J.; Kobayashi, Y.; Currie, P. J. (2004). "Ornithomimosauria". In Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 137–150. doi:10.1525/california/9780520242098.003.0008. ISBN 9780520242098.

- R. Barsbold. 1976. K evolyutsii i sistematike pozdnemezozoyskikh khishchnykh dinozavrov [The evolution and systematics of late Mesozoic carnivorous dinosaurs]. In N. N. Kramarenko, B. Luvsandansan, Y. I. Voronin, R. Barsbold, A. K. Rozhdestvensky, B. A. Trofimov & V. Y. Reshetov (eds.), Paleontology and Biostratigraphy of Mongolia. The Joint Soviet-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition, 3:68-75 Transactions

- Sereno, P.C. (1998). "A rationale for phylogenetic definitions, with application to the higher-level taxonomy of Dinosauria". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Abhandlungen. 210 (1): 41–83. doi:10.1127/njgpa/210/1998/41.

- Li Xu, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, Junchang Lü, Yuong-Nam Lee, Yongqing Liu, Kohei Tanaka, Xingliao Zhang, Songhai Jia and Jiming Zhang (2011). "A new ornithomimid dinosaur with North American affinities from the Late Cretaceous Qiupa Formation in Henan Province of China". Cretaceous Research. 32 (2): 213–222. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2010.12.004.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rothschild, B., Tanke, D. H., and Ford, T. L., 2001, Theropod stress fractures and tendon avulsions as a clue to activity: In: Mesozoic Vertebrate Life, edited by Tanke, D. H., and Carpenter, K., Indiana University Press, p. 331-336.

- Osmólska H, Roniewicz E & Barsbold R (1972). "A new dinosaur, Gallimimus bullatus n. gen.,n. sp. (Ornithomimidae) from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia". Paleontol. Polonica. 27: 103–143.

- Paul, regarding his comparative speed estimates, notes that "... just how swift is swift? In hard, precise measure, this can be a real can of worms; for just how fast living animals run is not well known." (Paul, G.S. 1988. Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. New York: Simon & Schuster.)

Further reading

- Russell, D. A. (1969). "A new specimen of Stenonychosaurus from the Oldman Formation (Cretaceous) of Alberta". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 6 (4): 595–612. Bibcode:1969CaJES...6..595R. doi:10.1139/e69-059.

- Cranfield, I. (2004). The Illustrated Directory of Dinosaurs and other Prehistoric Creatures (pp. 30–33). Greenwich Editions. ISBN 0-86288-662-7.

- Reisdorf, A.G.; Wuttke, M. (2012). "Re-evaluating Moodie's Opisthotonic-Posture Hypothesis in fossil vertebrates. Part I: Reptiles - The taphonomy of the bipedal dinosaurs Compsognathus longipes and Juravenator starki from the Solnhofen Archipelago (Jurassic, Germany)". Palaeobiodiversity and Palaeoenvironments. 92: 119–168. doi:10.1007/s12549-011-0068-y. S2CID 129785393.

External links

Media related to Struthiomimus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Struthiomimus at Wikimedia Commons

.jpg.webp)