Government of Vichy France

The Government of Vichy France was the collaborationist ruling regime or government in Nazi-occupied France during the Second World War. Of contested legitimacy, it was headquartered in the town of Vichy in occupied France, but it initially took shape in Paris under Marshal Philippe Pétain as the successor to the French Third Republic in June 1940. The government remained in Vichy for four years, and fled into exile to Germany in September 1944 after the Allied invasion of France. It operated as a government-in-exile until April 1945, when the Sigmaringen enclave was taken by Free French forces. Pétain was brought back to France, by then under control of the Provisional French Republic, and put on trial for treason.

French State | |

|---|---|

| 1940–1944[1] | |

| Motto: "Travail, Famille, Patrie" ("Work, Family, Fatherland") | |

| Anthem: "La Marseillaise" (official) "Maréchal, nous voilà!" (unofficial)[2] ("Marshal, here we are!") | |

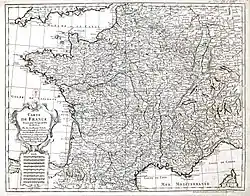

The French State in 1942:

| |

The gradual loss of all Vichy territory to Free France and the Allied powers | |

| Status |

|

| Capital | |

| Capital-in-exile | Sigmaringen |

| Common languages | French |

| Government | Provisional republic under a collaborationist authoritarian dictatorship |

| Chief of State | |

• 1940–1944 | Philippe Pétain |

| Prime Minister | |

• 1940–1942 | Philippe Pétain |

• 1940 (acting) | Pierre Laval |

• 1940–1941 (acting) | P.É. Flandin |

• 1941–1942 (acting) | François Darlan |

• 1942–1944 | Pierre Laval |

| Legislature | National Assembly |

| Historical era | World War II |

| 22 June 1940 | |

| 10 July 1940 | |

| 8 November 1942 | |

| 11 November 1942 | |

| Summer 1944 | |

| 9 August 1944[1] | |

• Capture of the Sigmaringen enclave | 22 April 1945 |

| Currency | French franc |

| |

| History of France |

|---|

|

| Topics |

| Timeline |

|

|

Background

A hero of World War I,[3] known for applying the lessons of the Second Battle of Champagne to minimize casualties in the Battle of Verdun, Pétain became commander of French forces in 1917.[3] He came to power in World War II as a reaction to the stunning defeat of France in early 1940. Pétain blamed a lack of men and material for the defeat,[4] but had himself participated in the egregious miscalculations that led to the Maginot Line, and the belief that the Ardennes were impenetrable.[5] Nonetheless, Pétain's cautious and defensive tactics at Verdun had won him acclaim from a devastated military, and poet Paul Valéry called him "the champion of France".[6]

He became Vice-Premier under Paul Reynaud in May 1940, when the only question was whether the French Army should surrender or the French government sue for an armistice.[6] After President Albert Lebrun appointed Pétain prime minister on 16 June, the government signed an armistice with Germany on 22 June 1940.

With France fallen to the Germans, the British judged the risk was too high of the French Navy falling into German hands, and a few days later, in the attack on Mers-el-Kébir on 3 July 1940, they sank one battleship and damaged five others, also killing 1,297 French servicemen. Pétain severed diplomatic relations with the United Kingdom on 8 July. The next day the National Assembly voted to revise the constitution, and the following day, 10 July, the National Assembly granted absolute power to Pétain, thus ending the French Third Republic.[7] In retaliation for the attack at Mers el Kébir, French aircraft raided Gibraltar on 18 July but did little damage.

Pétain established an authoritarian government at Vichy,[8][9] with central planning a key feature, as well as tight government control. French conventional wisdom, particularly in the administration of François Mitterrand, long held that the French government under Petain had merely sought to make the best of a bad situation. While Vichy policy towards the Germans was at least in part founded in concern for the 1.8 million French prisoners of war,[10] as President Jacques Chirac subsequently acknowledged, even Mussolini stood up to Hitler and in so doing saved the lives of thousands of Jews, many of them French. Antisemitism in France did not begin under Pétain, but it certainly became a key characteristic of his time in power as manifested in Vichy anti-Jewish legislation.

Third Republic

Until the invasion, the French Third Republic had been the government of France since the defeat of Napoleon III and the end of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. It was dissolved by the French Constitutional Law of 1940 which gave Pétain the power to write a new constitution. He interpreted this to mean that the previous constitution, outlined in the French Constitutional Laws of 1875, no longer constrained him.

In the wake of the Battle of France that culminated in the disaster at Dunkirk, the French government declared Paris an open city and relocated to Bordeaux on 10 June 1940 in order to avoid capture. On 22 June, France and Germany signed the Second Armistice at Compiègne. The Vichy government led by Pétain replaced the Third Republic. It administered the zone libre in the south of France until November 1942, when Germans and Italians occupied the zone under Case Anton following the Allied landings in North Africa under Operation Torch. Germany occupied northern France and the Atlantic coast, and the Italians, a small territory in the southeast.

Transition to the French State

At the time of the armistice the French and the Germans both thought Britain would come to terms any day, so it included only temporary arrangements. France agreed to its soldiers remaining prisoners of war until hostilities ceased. The terms of the armistice sketch out a "French State" (État français), whose sovereignty and authority in practice were limited to the zone libre, although in theory it administered all of France. The military administration of the occupied zone was in fact a Nazi dictatorship. However, the fiction of French independence was so important to Laval in particular that he agreed to requisition French workers for Germany to prevent the Germans from doing it unilaterally for the zone occupée alone.

The Vichy régime considered itself the legitimate government of France, but Charles de Gaulle, who had escaped to England, declared a government in exile in London, and broadcast appeals to French citizens to resist the occupying forces. Britain shortly thereafter recognized his Empire Defence Council as the legitimate French government. Under the terms of the armistice France was allowed a small army to defend itself and to administer its colonies. Most of these colonies simply recognized the shift in power, but their allegiance to Vichy shifted once the Allies invaded North Africa in Operation Torch. Britain however outraged the French by bombing their fleet because the British were unwilling to risk it falling into Axis hands.

Alsace-Lorraine, which France and Germany had long disputed, was simply annexed. When Allied forces landed in North Africa under Operation Torch, the Nazis annexed the free zone in Case Anton, Germany's response.

Pétain administration under Third Republic

Pétain government | |

|---|---|

| |

| Date formed | 16 June 1940 |

| Date dissolved | 10 July 1940 |

| People and organisations | |

| President of the Republic | Albert Lebrun |

| Head of government | Philippe Petain |

| Member party | SFIO |

| Status in legislature | Government of National Union 536/608 |

| History | |

| Incoming formation | Fall of France |

| Outgoing formation | Constitutional Law of 1940 |

| Predecessor | Paul Reynaud government |

| Successor | Laval 5/Vichy government • Empire Defense Council/Free France |

The Philippe Pétain administration was the last administration of the French Third Republic, succeeding on 16 June 1940 to Paul Reynaud's cabinet. It formed in the middle of the Battle of France debacle, when Nazi Germany invaded France at the beginning of the Second World War. It was led until 10 July 1940 by Philippe Pétain, and favored the armistice, unlike General de Gaulle, who favored fighting on in the Empire Defense Council[lower-alpha 1] It was followed by the fifth administration of Pierre Laval, the first administration of the Vichy France regime.

Formation

Paul Reynaud, who had been the French President of the Council since 22 March 1940, resigned early on the evening of 16 June, and President Albert Lebrun called for Pétain to form a new government.

Pétain recruited Adrien Marquet for Interior and Pierre Laval for Justice. Laval wanted an offer of Justice. On the advice of François Charles-Roux, the Secretary-General for Foreign Affairs, and with the support of Maxime Weygand and Lebrun, Pétain stood firm, which led Laval to withdraw, followed by Marquet in solidarity. After the armistice, Raphaël Alibert convinced Pétain of the need to rely on Laval, and the two rejoined the government.[12]

Pétain obtained the participation of the SFIO by bringing back Albert Rivière and André Février with the agreement of Léon Blum.

The following is a list of the French government ministers in the administration of Pétain under the Third Republic.

Composition

| Title | Office holder | Party |

|---|---|---|

| Président du Conseil | Philippe Pétain | SE |

| Vice-Presidents of the Council | Camille Chautemps (16 June – 12 July)[13] | RAD |

| Pierre Laval (starting 23 June 1940) | SE | |

| Ministers of State | ||

| Ministers of State | Camille Chautemps | RAD |

| Adrien Marquet (starting 23 June 1940) | SE | |

| Pierre Laval (starting 23 June 1940) | SE | |

| Ministers | ||

| Minister for Foreign Affairs | Paul Baudoin | SE |

| Minister of Finance and Commerce | Yves Bouthillier | SE |

| Minister of War | Louis Colson | SE |

| Ministre of National Defense | Maxime Weygand | SE |

| Guardian of the Seals, Minister of Justice | Charles Frémicourt | SE |

| Minister of National Education | Albert Rivaud | SE |

| Minister of the Interior | Charles Pomaret | USR |

| Adrien Marquet (starting 27 June 1940) | SE | |

| Minister of the Merchant and Military Marine | François Darlan | SE |

| Minister of Air | Bertrand Pujo | SE |

| Minister of Public Works and Information | Ludovic-Oscar Frossard | USR |

| Albert Chichery | RAD | |

| Minister of Transmissions | André Février (starting 23 juin 1940) | SFIO |

| Minister of the Colonies | Albert Rivière | SFIO |

| Minister of Labour and Public Health | André Février | SFIO |

| Charles Pomaret (starting 27 June 1940) | USR | |

| Minister for Veterans and the French Family | Jean Ybarnegaray | PSF |

| High Commissioner for French Propaganda | Jean Prouvost (starting 19 June 1940) | SE |

| Commissioners-General | ||

| Commissioner-General for Resupply | Joseph Frédéric Bernard (starting 18 June 1940) | SE |

| Commissionner-General for National Reconstruction | Aimé Doumenc (starting 26 June 1940) | SE |

| Under-Secretaries of State | ||

| Under-Secretary of State to the Office of the Council President | Raphaël Alibert | SE |

| Under-Secretary of State for Refugees | Robert Schuman | PDP |

End of administration

On 10 July 1940, the French National Assembly Assemblée nationale met in Vichy and voted to give absolute power to Pétain in the Constitutional Law of 1940, effectively dissolving itself, and ending the Third Republic. The Vichy regime began.

Vichy governments

Pétain and the French State

In the French State under Pétain, French authorities willingly enacted and enforced antisemitic laws, unprompted by Berlin. His collaborationist government helped send 75,721 Jewish refugees and French citizens to Nazi death camps.[14]

First Laval administration (1940)

Pierre Laval government | |

|---|---|

| Date formed | 16 July 1940 |

| Date dissolved | 13 December 1940 |

| People and organisations | |

| Head of State and President of the Council | Philippe Pétain |

| Vice-President of the Council | Pierre Laval |

| Member party | SFIO |

| History | |

| Incoming formation | Constitutional Law of 1940 |

| Predecessor | Pétain government |

| Successor | Flandin regime |

The fifth government formed by Pierre Laval was the first administration formed by Pétain under the Vichy regime after the vote of 10 July 1940 ceded full constituent powers to Pétain. The government ended on 13 December 1940 with Laval's dismissal. This administration was not recognized as legitimate by the Empire Defense Council of the government of Free France, which the British Government had quickly recognized as the legitimate government of France following De Gaulle's radio appeals to the French public.

Formation

The government of Philippe Pétain signed the armistice with Germany on 22 June 1940, put an end to the Third Republic on 10 July 1940 by a vote conveying full powers to Pétain and followed up with three Vichy Constitutional Acts on 11 July. Meanwhile, on 11 July General de Gaulle created the Empire Defense Council, which was recognized by the British Government as the legitimate successor of the Third Republic, which had allied itself with Great Britain in the war against the Nazis.

On 12 July 1940 Pétain named Pierre Laval, second Minister of State of the last government of the Third Republic under Philippe Pétain[15] as vice-president of the Council,[16] while Pétain remained simultaneously head of state and head of government. Constitutional Act #4 made Laval next in the line of succession should something happen to Pétain.[17] On 16 July, Pétain formed the first government of the Vichy régime and kept Pierre Laval on as vice-president of the Council.

Laval's administration more or less coincides with the arrival in France of Fritz Sauckel, tasked by Hitler with procuring qualified manpower. Until then, fewer than 100 000 French workers had voluntarily travelled to Germany to work[18] Refusal to send 150 000 skilled workers had been one of the causes of the fall of Darlan.[19] Sauckel demanded 250,000 additional workers before the end of July 1942.

Laval fell back on his favorite tactic of negotiating, stalling for time, and seeking reciprocation. He proposed the relève, in which a prisoner of war would be freed for every three workers sent to Germany, and announced it 22 June 1942, after the same day, in a letter to Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German minister of foreign affairs, Laval framing the relève policy as French participation, by providing workers, in the German war effort.[20]

"They give their blood. Give your labour to save Europe from Bolshevism". Nazi propaganda leaflet suggesting French workers travel to Germany to support the war effort on the eastern front (1943)[21]

The voluntary relève, was replaced by the Service du travail obligatoire (STO) which began in August 1942 throughout occupied Europe. To Sauckel, the relève had failed, since fewer than 60 000 French workers had gone to Germany by the end of August. He threatened to issue an ordonnance to requisition male and female manpower. This ordonnance would only have had effect in the occupied zone. Laval negotiated a French law covering both zones instead.[22] Laval put workplace inspection, the police and the gendarmerie at the service of forced impressments of labor, and tracking Service du travail obligatoire scofflaws.[23] Forced impressments of workers, guarded by gendarmes until they boarded a train, drew hostile reactions. On 13 October 1942 the Oullins incidents broke out in the suburbs of Lyon, where workers at the railway station went on strike.[24] Someone wrote "Laval assassin!" (Laval murderer) on the trains.[24] The government was forced to back away; on 1 December 1942 only 2,500 requisitioned workers had left the southern zone.[23] On 1 January 1943, Sauckel demanded, in addition to the 240,000 workers already sent to Germany, a new contingent of 250,000 men, before mid-March[25] To meet these objectives, German forces organised ineffectively brutal raids, which led Laval to propose to the Council of Ministers on 5 February 1943 legislation creating the STO, under which youth born in 1920-1922 were requisitioned for work service in Germany[26] Laval mitigated his legislation with many exceptions.[26]

In all, 600 000 men left between June 1942 and August 1943[27] despite what Sauckel denounced in a letter to Hitler as "pure and simple sabotage", after meeting more than seven hours on 6 August 1943 with Laval, who again attempted to minimize the number of requisitioned workers and refused to his demand for 50 000 workers for Germany before the end of 1943.[28]

On 15 September 1943, Reich minister for Armament and War Production Albert Speer reached an agreement with Laval minister Jean Bichelonne[29] — an agreement Laval was counting on to "block the deportation machine".[28] Many businesses working for Germany were removed from Sauckel's requisition.[29] Individuals were protected but the French economy as a whole was integrated into that of Germany. In November 1943, Sauckel demanded,[27] without much success, 900 000 additional workers.[29] On orders from Berlin, French workers stopped leaving for Germany on 7 June 1944, after Allied landings in Normandy.[30]

In the end, the STO caused thousands of young réfractaires to embrace the Resistance, which created the maquis.[31] In the eyes of the French, Laval took ownership of the measures imposed by Sauckel and became the French minister who sent French workers to Germany.[18]

Initial composition

- Head of the French State, President of the Council,[32] Philippe Pétain.

- Vice president of the Council in charge of Information (18 July 1940)[33] and secretary of state for foreign afairs from 28 octobre 1940 (dismissed 13 décembre 1940) : Pierre Laval

- Keeper of the Seals (Garde des Sceaux) and Minister Secretary of State for Justice (until January 1941): Raphaël Alibert

- Minister Secretary of State for Finance (until April 1942): Yves Bouthillier

- Minister Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs (until 28 October 1940), then Minister Secretary of State for the President of the Council (28 October 1940–2 January 1941):[34] Paul Baudouin

- Secretary of State for Food and Agriculture, then Minister of Agriculture (December 1940-April 1942): Pierre Caziot

- Minister Secretary of State for Industrial Production and Labour (until February 1941), then Minister of Labour (until April 1942): René Belin

- Minister Secretary of State for National Defence (dismissed from the Government as of September 1940): General Maxime Weygand (then Delegate General in North Africa and Commander-in-Chief of the French forces in North Africa until November 1941)

- Secretary of State for War (Army) (discharged from the government as of September 1940: General Louis Colson

- Secretary of State for Aviation (dismissed from the government as of September 1940: General Bertrand Pujo

- Secretary of State, then Minister of the Navy: Admiral François Darlan

- Minister Secretary of State for the Interior (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): Adrien Marquet

- Minister Secretary of State for Public Education and Fine Arts (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 because he was a former parliamentarian): Émile Mireaux

- Minister Secretary of State for Family and Youth (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): Jean Ybarnegaray

- Minister Secretary of State for Communications (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): François Piétri

- Minister Secretary of State for the Colonies (dismissed from the government as of September 1940 as a former parliamentarian): Henry Lémery

16 July 1940

The following joined on 16 July 1940:

- Secretary General for Justice: Georges Dayras

- Secretary General for Public Finance: Henri Deroy

- Secretary General to the Presidency of the Council: Jean Fernet

- Secretary General for Economic Affairs: Olivier Moreau-Néret

- Secretary General for Public Works and Transport: Maurice Schwartz (politician)

September 1940

The following joined in September 1940, replacing eight dismissed ministers:

- Minister of the Interior : Marcel Peyrouton

- Minister of War (September 1940) and Commander-in-Chief of the Land Forces (until November 1941): General Charles Huntziger

- Secretary of State for Aviation: General Jean Bergeret

- Secretary of State for Communications (until April 1942: Jean Berthelot

- Secretary of State for Public Education and Youth (until 13 December 1940: Georges Ripert

- Secretary of State for the Colonies (until April 1942: Admiral Charles Platon

- Secretary General for Youth: Georges Lamirand

18 November 1940

The following were appointed on 18 November 1940:

- Secretary General of the Head of State: Émile Laure

Transition 13 December 1940

Laval was sacked by Pétain on 13 December 1940. This came as a surprise to Laval. He was replaced by a triumvirate of Flandin, Darlan, and General Charles Huntziger. This caused friction with Hitler's representative Otto Abetz, who was furious about Vichy's insufficient collaboration, and closed the demarcation line in response.[35]

Flandin regime

Pierre Flandin government | |

|---|---|

Time cover, 4 February 1935 | |

| Date formed | 14 December 1940 |

| Date dissolved | 9 February 1941 |

| People and organisations | |

| Head of State and President of the Council | Philippe Pétain |

| Vice-President of the Council | Pierre-Étienne Flandin |

| Member party | SFIO |

| History | |

| Predecessor | Laval government |

| Successor | Darlan government |

The second government of Pierre-Étienne Flandin was the second government of the Vichy regime in France, formed by Philippe Pétain. It succeeded the first Pierre Laval government on 14 December 1940 and ended on 9 February 1941.

The Germans were unhappy after the sacking of Laval on 13 December, and suspicious of Flandin and whether he was sufficiently collaborationist. Darlan met with Hitler on 25 December and endured his anger, assuring Hitler that Vichy was still committed to collaboration. There followed several months of intrigue while Flandin was in power, during which Pétain even considered taking Laval back, however Laval was now no longer interested in anything other than supreme power. The impasse was lifted after the Germans had a change of heart with respect to Darlan, although not toward Flandin who they considered insufficiently collaborationist, and this led to Flandin's resignation on 9 February 1941, and Darlan's accession.[35]

Carryovers from Laval

The majority of ministers, secretaries, and delegates were carried over from the Laval government that ended 13 December 1940.

- Head of the French State, Council President: Philippe Pétain.

- Guardian of the Seals and Minister-Secretary of the State for Justice (until January 1941): Raphaël Alibert

- Minister of Finance (until April 1942): Yves Bouthillier

- Minister-Secretary of the State to the Council President's Office (28 October 1940 to 2 January 1941) and Minister of Information (December 1940 to 2 January 1941): Paul Baudouin

- Minister of Agriculture (December 1940 to April 1942): Pierre Caziot

- Minister of Industrial Production and Labour (until February 1941): René Belin

- Delegate General to North Africa and commander in chef of Vichy forces in North Africa (until November 1941): General Maxime Weygand

- Minister of the Marine: Admiral François Darlan

- Minister of the Interior: Marcel Peyrouton

- Minister of War (September 1940) and Commander in chief of ground forces (until November 1941): General Charles Huntziger

- Secretary of the State for Aviation: General Jean Bergeret

- Secretary of the State for Communications (until April 1942): Jean Berthelot

- Secretary of the State for the Colonies (until April 1942): Admiral Charles Platon

- Secretary General for Justice: Georges Dayras

- Secretary General for Public Finance: Henri Deroy

- Secretary General to the Office of Council President: Jean Fernet

- Secretary General for Youth: Georges Lamirand

- Secretary General of the Head of State: Émile Laure

- Secretary General for Economic Questions: Olivier Moreau-Néret

- Secretary General for Transport and Public Works: Maurice Schwarz

Named 13 December 1940

- Vice-President of the Council and Minister for Foreign Affairs: Pierre-Étienne Flandin

- Minister of National Education: Jacques Chevalier

- Secretary of State for Supplies: Jean Achard (politician)

- Secretary General for Public Instruction: Adolphe Terracher

Named 27 January 1941

- Keeper of the Seals and Minister Secretary of State for Justice (January 1941 - resigned March 1943): Joseph Barthélemy

Named 30 January 1941

- Secretary General for Procurement: Jacques Billiet

Resignation 9 February 1941

Flandin's short period in power was marked by intrigue and Hitler's suspicions about Vichy's level of collaboration with Germany. When it was clear that Darlan had more confidence in Berlin than Flandin did, Flandin resigned on 9 February 1941, leaving the way clear for Darlan.[35]

Darlan regime

François Darlan government | |

|---|---|

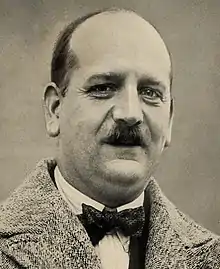

François Darlan, in an undated image. | |

| Date formed | 10 February 1941 |

| Date dissolved | 18 April 1942 |

| People and organisations | |

| Head of State and President of the Council | Philippe Pétain |

| Vice-President of the Council | François Darlan |

| Member party | SFIO |

| Status in legislature | none; full powers to Pétain |

| History | |

| Incoming formation | named by Pétain after Flandin quit |

| Outgoing formation | Laval accession demanded by Germany |

| Predecessor | Flandin regime |

| Successor | Laval government (1942–1944) |

After two years at the head of the Vichy government, Admiral Darlan was unpopular and had strengthened ties with Vichy forces, in an expanded collaboration with Germany which seemed to him the least bad solution, and had conceded a great deal, turning over the naval bases at Bizerte and Dakar, an air base in Aleppo in Syria, as well as vehicles, artillery and ammunition in North Africa and Tunisia, in addition to arming the Iraqis. In exchange Darlan wanted the Germans to reduce the constraints under the armistice, free French prisoners, and eliminate the ligne de démarcation. This irritated the Germans. On 9 March 1942, Hitler signed a decree giving France a chief of the SS and police leader (HSSPF) tasked with organizing the "Final Solution", following the Wannsee Conference with the French police. The Germans demanded the return of Laval to power, and broke off contact. The Americans intervened on 30 March to prevent another Laval administration.

Timeline

- 14 May 1941, arrest and detainment of 3,747 Jews in internment camps in the Green ticket roundup.

- 2 July 1942, Bousquet and Carl Oberg signed an agreement to collaborate in police matters.

- On 16 and 17 July 1942, Vichy police organised the Vel' d'Hiv Roundup.

- 19 August 1942, Allies launched Operation Jubilee on the beach at Dieppe to test German defenses.

- On 3 November 1942, General Erwin Rommel lost the battle of El-Alamein, halting the Italian-German advance towards the Suez Canal and began the retreat of the Afrika Korps towards Tunisia.

- On 8 November 1942, the Allies launched landings in Algeria and Morocco (Operation Torch).

- 11 November 1942, the Wehrmacht invaded the previously-unoccupied zone libre, and occupied Tunis and Bizerte, without fighting.

- 19 November 1942, the Army of Africa again took up the fight against the Germans in Tunisia, in Majaz al Bab.

- On 27 November 1942, the French fleet sank its ship in Toulon and the Armistice Army dissolved.

- On 7 December 1942, French West Africa joined the Allies.

- On 24 December 1942, Admiral François Darlan was assassinated in Algiers by a young monarchist, Fernand Bonnier de La Chapelle.

- February 1943 - German troops are surrounded at Stalingrad.

- 30 January 1943, Laval created the French Milice (militia).

- March 1943, French Guiana joined the Allies.

- 13 May 1943, Axis forces surrender in Tunisia.

- 24 May 1943, first Vichy Milice member is killed by the French Resistance.

- 31 May 1943, Vichy forces pinned in Alexandria joined the African Free French Naval Forces.

- 15 July 1943, French Antilles joined Free France.

- 5 October 1943, Corsica became the first region of Metropolitan France liberated by the French Liberation Army and the Italian Armed Forces of the Occupation.

- 1 January 1944, Joseph Darnand is named Secretary-General for Maintaining Order.

- 6 June 1944, Allies launch Operation Overlord in Normandy (D Day).

- 15 August 1944, Allies land in Provence and move from Normandy towards Paris, and the liberation of France accelerates.

- 17 August 1944, Pierre Laval, head of government and Minister for Foreign Affairs, held his last council meeting in Paris. The Germans wanted to maintain a "French government" in the hope of stabilizing the front in Eastern France and in case they could reconquer it.[36] The same day, in Vichy, Cecil von Renthe-Fink, the German minister-delegate, asked Pétain to travel to the northern zone, but he refused and asked for this instruction to be made in writing.[37]

- 18 August, von Renthe-Fink asks twice more.

- 19 August, at 11:30 am, von Renthe-Fink returned to the hôtel du Parc, résidence of the Maréchal, accompanied by General von Neubroon, who said he had "formal orders from Berlin".[37] Written instructions were given to Petain: "The government of the Reich orders the transfer of the head of state, even against his will".[37] When the maréchal refused again, the Germans threatened to have the Wehrmacht bomb Vichy.[37] After asking the Swiss ambassador, Walter Stucki, to witness the blackmail to which he was subjected, Pétain surrendered and ended the Laval administration.

- 20 August 1944, the Germans took Pétain, against his will,[38] from Vichy to the château de Morvillars near Belfort.[39][40]

Second Laval administration (1942-1944)

Pierre Laval government 1942–44 | |

|---|---|

| Date formed | 18 April 1942 |

| Date dissolved | 19 August 1944 |

| People and organisations | |

| Head of French State | Philippe Pétain |

| Head of government | Pierre Laval |

| Member party | SFIO |

| Status in legislature | none; full powers to Pétain |

| History | |

| Incoming formation | Petain accedes to German demands for Laval's return |

| Outgoing formation | dismissed by Petain under German orders |

| Predecessor | Darlan government |

| Successor | Sigmaringen enclave |

After two years at the head of the Vichy regime, François Darlan's government was unpopular, a victim of the fool's bargain he had made with the Germans. Darlan committed Vichy into further collaboration with Germany as the least bad solution for him, giving up much ground: handover of the naval bases at Bizerte and Dakar, an air base in Aleppo (Syria), vehicles, artillery and ammunition in North Africa, Tunisia, not to mention the delivery of arms to Iraq.

In exchange, Darlan asked the Germans for a quid pro quo (reduction of the constraints of the armistice: release of French prisoners, elimination of the demarcation line and fuel oil for the French fleet), which irritated them.

On 9 March 1942, Hitler signed the decree endowing France with a "Higher SS and police leader" (HSSPf) responsible for organizing the Final Solution after the Wannsee Conference with the French Police. The Germans then demanded that Pierre Laval return to power, and in the meantime they broke off all contact.

On 30 March 1942, the Americans intervened in Vichy against Laval's return to power.

Composition

- French Head of State, President of the Council:[41] Marshal Philippe Pétain.

- Head of Government, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of the Interior and Minister of Information : Pierre Laval

- Minister of War: Eugène Bridoux

- Minister of Finance and National Economy: Pierre Cathala

- Minister of Industrial Production: Jean Bichelonne

- Minister of Labour: Hubert Lagardelle

- Minister of Justice: Joseph Barthélemy

- Minister of the Navy: Gabriel Auphan

- Minister of Air: Jean-François Jannekeyn

- Minister of National Education: Abel Bonnard

- Minister of Agriculture: Jacques Le Roy Ladurie

- Minister of Supply : Max Bonnafous

- Minister of Colonies : Jules Brévié

- Minister of Family and Health : Raymond Grasset

- Minister of Communications: Robert Gibrat

- Minister of State: Lucien Romier

- General Delegate of the government in the occupied territories: Fernand de Brinon (de Brinon was later head of the Sigmaringen enclave)

- Secretary of State to the Head of Government: Fernand de Brinon

- Secretary General to the Police: René Bousquet

- Secretary General of the government: Jacques Guérard

- Secretary of State for Information: Paul Marion, until 5 January 1944

- Secretary General for Administration of the Ministry of the Interior: Georges Hilaire, until 15 March 1944

- Commissioner General for Sport : Joseph Pascot

- Secretary General for Health: Louis Aublant until 17 December 1943

- Secretary General for Supply: Jacques Billiet until 6 June 1942 and from 15 November 1943 to June 1944.

- Secretary General for Justice: Georges Dayras until 25 January 1944 and from 2 March 1944 to 20 August 1944

- Secretary General for Public Finance: Henri Deroy until 1 May 1943

- Secretary-General for Economic Affairs: Jean Filippi until 16 June 1942.

- Secretary General of Fine Arts: Louis Hautecœur until 1 January 1944

- Secretary General for Youth: Georges Lamirand until 24 March 1943

- Commissioner General of the Youth Works: Joseph de La Porte du Theil until 4 January 1944

- Secretary General of the Head of State: Émile Laure until 15 June 1942

- Secretary General to the Family : Philippe Renaudin

- Secretary-General for Foreign Affairs: Charles-Antoine Rochat

- Secretary General for Public Works and Transport: Maurice Schwartz

- Secretary General for Public Instruction: Adolphe Terracher until 2 January 1944

- Secretary General for Labour and Manpower: Jean Terray until June 1942

- Commissariat General for Jewish Questions: Xavier Vallat until 5 May 1942

Dissolution and transition

On 17 August 1944, Pierre Laval, head of government and minister of foreign affairs, held his last council of government with five ministers.[42] With permission from the Germans, he attempted to call back the prior National Assembly with the goal of giving it power[43] and thus impeding the communists and de Gaulle.[44] So he obtained the agreement of German ambassador Otto Abetz to bring Édouard Herriot, (President of the Chamber of Deputies) back to Paris.[44] But ultra-collaborationists Marcel Déat and Fernand de Brinon protested against this to the Germans, who changed their minds[45] and took Laval to Belfort[46] along with the remains of his government, "to assure its legitimate security", and arrested Herriot.[47]

Sigmaringen enclave

On 20 August 1944 Pierre Laval was taken to Belfort[48] by the Germans along with the remains of his government, "to assure its legitimate security". Vichy head of state Marshal Philippe Pétain was conducted against his will to Belfort on 20 August 1944. A governmental commission directed by Fernand de Brinon was proclaimed on 6 September.[49] On 7 September, they were taken ahead of the advancing Allied Forces out of France to the town of Sigmaringen, where they arrived on the 8th, where other Vichy officials were already present.[50]

Hitler requisitioned the Sigmaringen Castle for use by top officials. This was then occupied and used by the Vichy government-in-exile from September 1944 to April 1945. Pétain resided at the Castle, but refused to cooperate, and kept mostly to himself,[49] and ex-Prime Minister Pierre Laval also refused.[51] Despite the efforts of the collaborationists and the Germans, Pétain never recognized the Sigmaringen Commission.[52] The Germans, wanting to present a facade of legality, enlisted other Vichy officials such as Fernand de Brinon as president, along with Joseph Darnand, Jean Luchaire, Eugène Bridoux, and Marcel Déat.[53]

On 7 September 1944,[54] fleeing the advance of Allied troops into France, while Germany was in flames and the Vichy regime ceased to exist, a thousand French collaborators (including a hundred officials of the Vichy regime, a few hundred members of the French Militia, collaborationist party militants, and the editorial staff of the newspaper Je suis partout) but also waiting-game opportunists[lower-alpha 2] also went into exile in Sigmaringen.

The commission had its own radio station (Radio-patrie, Ici la France) and official press (La France, Le Petit Parisien), and hosted the embassies of the Axis powers: Germany, Italy and Japan. The population of the enclave was about 6,000, including known collaborationist journalists, the writers Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Lucien Rebatet, the actor Robert Le Vigan, and their families, as well as 500 soldiers, 700 French SS, prisoners of war and French civilian forced laborers.[55] Inadequate housing, insufficient food, promiscuity among the paramilitaries, and lack of hygiene facilitated the spread of numerous illnesses including flu and tuberculosis) and a high mortality rate among children, ailments that were treated as best they could by the only two French doctors, Doctor Destouches, alias Louis-Ferdinand Céline and Bernard Ménétrel.[54]

On 21 April 1945 General de Lattre ordered his forces to take Sigmaringen. The end came within days. By the 26th, Pétain was in the hands of French authorities in Switzerland,[56] and Laval had fled to Spain.[51] Brinon,[57] Luchaire, and Darnand were captured, tried, and executed by 1947. Other members escaped to Italy or Spain.

Transition

The liberation of France in 1944 dissolved the Vichy government. The Provisional Consultative Assembly requested representation, leading to the Provisional Government of the French Republic (French: Gouvernement provisoire de la République française, GPRF), also known as the French Committee of National Liberation. Past collaborators were discredited and Gaullism and communism became political forces.

De Gaulle led the GPRF 1944-1946 while negotiations took place for a new constitution, to be put to a referendum. De Gaulle advocated a presidential system of government, and criticized the reinstatement of what he pejoratively called "the parties system". He resigned in January 1946 and was replaced by Felix Gouin of the French Section of the Workers' International (Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière, SFIO). Only the French Communist Party (Parti communiste français, PCF) and the socialist SFIO supported the draft constitution, which envisaged a form of unicameralism. This constitution was rejected in the 5 May 1946 referendum.

French voters adopted the constitution of the Fourth Republic on 13 October 1946.

Other

After the fall of France on 25 June 1940 many French colonies were initially loyal to Vichy. But eventually the overseas empire helped liberate France; 300,000 North African Arabs fought in the ranks of the Free French.[58] French Somaliland, an exception, got a governor loyal to Vichy on 25 July. It surrendered to Free French forces on 26 December 1942.[59] The length and extent of each colony's collaboration with Vichy ran a gamut however; antisemitic measures met an enthusiastic reception in Algeria, for example.[60]

Operation Torch on 8 November landed Allied troops at Oran and Algiers (Operation Terminal) as well as at Casablanca in Morocco, to attack Vichy territories in North Africa—Morocco, Algeria and Tunisia—then take Axis forces in the Western Desert in their rear from the east.[61] Allied shipping had needed to supply troops in Africa via the Cape of Good Hope, so the Mediterranean ports were strategically valuable.

The Battle of Dakar against the Free French Forces in September 1940 followed the Fall of France. Authorities in West Africa declared allegiance to the Vichy regime, as did the colony of French Gabon in French Equatorial Africa (AEF). Gabon fell to Free France after the Battle of Gabon in November 1940, but West Africa remained under Vichy control until the Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942.

Jurisdiction and effectiveness

Collaboration with Germany

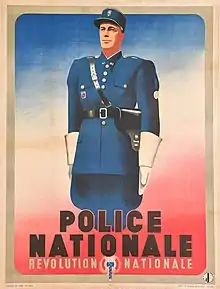

The German military administration cooperated closely with the Gestapo, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the intelligence service of the SS, and the Sicherheitspolizei (Sipo), its security police. It also drew support from the French authorities and police, who had to cooperate under the armistice, to round up Jews, anti-fascists and other dissidents, and from collaborationist auxiliaries like the Milice, the Franc-Gardes and the Groupe mobile de réserve. The Milice helped Klaus Barbie seize members of the resistance and minorities including Jews for detention.

The two main collaborationist political parties, the French Popular Party (PPF) and the National Popular Rally (RNP), each had 20,000 to 30,000 members. Collaborationists were fascists and Nazi sympathisers who collaborated for ideological reasons, unlike "collaborators", people who cooperated out of self-interest. A principal motivation and ideological foundation among collaborationists was anti-communism. Examples of these are PPF leader Jacques Doriot, writer Robert Brasillach and Marcel Déat (founder of the RNP).

Some Frenchmen also volunteered to fight for Germany or against Bolsheviks, such as the Legion of French Volunteers Against Bolshevism. Volunteers from this and other outfits later constituted the cadre of the 33rd Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Charlemagne (1st French).

Foreign relations

The French State was quickly recognized by the Allies, as well as by the Soviet Union, until 30 June 1941 and Operation Barbarossa. However France broke with the United Kingdom after the destruction of the French Fleet at Mers-el-Kebir. The United States took the position that Vichy should do nothing adverse to US interests that was not specifically required by the terms of the armistice. Canada maintained diplomatic relations with Vichy until the occupation of southern France in Case Anton by Germany and Italy in November 1942.[62]

In 1941, the Free French Forces fought with British troops against the Italians in Italian East Africa during the East African Campaign, and expanded operations north into Italian Libya. In February 1941, Free French Forces invaded Cyrenaica, led by Leclerc, and captured the Italian fort at the oasis of Kufra. In 1942, Leclerc's forces and soldiers from the British Long Range Desert Group captured parts of the province of Fezzan. At the end of 1942, Leclerc moved his forces into Tripolitania to join British Commonwealth and other FFF forces in the Run for Tunis.[63]

French India under Louis Bonvin announced after the fall of France that they would join the British and the French under Charles de Gaulle.[64]

Nearly 300,000 French Jews, 80% of those remaining, moved to the Italian zone of occupation to escape the Nazis.[65][66] The Italian Jewish banker Angelo Donati had convinced the Italian civil and military authorities to protect the Jews from French persecution.[67]

In January 1943 the Italians refused to cooperate with Nazi roundups of Jews living under their control and in March prevented them from deporting Jews from their zone.[68] German foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop complained to Mussolini that "Italian military circles ... lack a proper understanding of the Jewish question."[69] However, when the Italians signed the armistice with the Allies, German troops invaded the former Italian zone on 8 September 1943 and Alois Brunner, the SS official for Jewish affairs, formed units to search out Jews. Within five months, 5,000 Jews were caught and deported.[70]

Legitimacy

Given full constituent powers in the law of 10 July 1940, Pétain never promulgated a new constitution. A draft was written in 1941 and signed by Pétain in 1944, but never submitted nor ratified.[71][72]

The United States gave Vichy full diplomatic recognition, and sent Admiral William D. Leahy as ambassador.[73] President Roosevelt and Secretary of State Cordell Hull hoped to encourage elements in the Vichy government opposed to military collaboration with Germany. The Americans also wanted Vichy to resist German demands for its naval fleet or air bases in French-mandated Syria or to move war supplies through French territories in North Africa. Americans held that France should take no action not explicitly required by the terms of the armistice that could adversely affect Allied efforts in the war. The Americans ended relations with Vichy when Germany occupied the zone libre of France in late 1942.

The USSR maintained relations with Vichy until 30 June 1941, after the Nazis invaded Russia in Operation Barbarossa.

France for a long time took the position that the republic had been disbanded when power was turned over to Pétain, but officially admitted in 1995 complicity in the deportation of 76,000 Jews during WW II. President Jacques Chirac, speaking at the site of the Vélodrome d'Hiver, where 13,000 Jews were rounded up for deportation to death camps in July 1942, said: "France, on that day [16 July 1942], committed the irreparable. Breaking its word, it handed those who were under its protection over to their executioners", he said. Those responsible for the roundup were "450 policemen and gendarmes, French, under the authority of their leaders [who] obeyed the demands of the Nazis. .... the criminal folly of the occupiers was seconded by the French, by the French state".[74][75]

The police under Bousquet collaborated to the point where they themselves compiled the lists of Jewish residents, gave them yellow stars, and even requisitioned buses and SNCF trains to transport them to camps such as Drancy.

The French themselves distinguish between collaborators, and collaborationists, who agreed with Nazi ideology and actively worked to further their domestic policies, as opposed to the majority of collaborators who worked with the Nazis reluctantly, and in order to avoid consequences to themselves.

The international tribunal at Nuremberg called Vichy régime agreements with the Nazis for deportation of citizens and residents void ab initio due to their "immoral content".[76]

See also

- 7th Military Division (Vichy France)

- Army of the Levant

- Battle of the Netherlands

- Franc-Garde

- French prisoners of war in World War II

- Liberation of France

- Liberation of Paris

- Maurice Papon

- Milice

- Rene Bousquet

- Service du travail obligatoire

- The Holocaust in France

- Vichy 80

- Vichy French Air Force

- Vichy French Army

- Vichy French Navy

- Vichy Holocaust collaboration timeline

- Victor Emmanuel III of Italy

- Xavier Vallat

References

- Notes

- The Empire Defense Council was the government in exile of Free France, recognized by Winston Churchill after Pétain was given given full power to write a new constitution by the French National Assembly through the constitutional legislation of 11 July 1940,[11] on the web site of the law and economics faculty at Perpignan, mjp.univ-perp.fr, consulted 15 July 2006)

- "waiting-game opportunists": Attentistes in the original.

- Citations

- "Ordonnance du 9 août 1944 relative au rétablissement de la légalité républicaine sur le territoire continental – Version consolidée au 10 août 1944" [Law of 9 August 1944 Concerning the reestablishment of the legally constituted Republic on the mainland – consolidated version of 10 August 1944]. gouv.fr. Legifrance. 9 August 1944. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

Article 1: The form of the government of France is and remains the Republic. By law, it has not ceased to exist.

Article 2: The following are therefore null and void: all legislative or regulatory acts as well as all actions of any description whatsoever taken to execute them, promulgated in Metropolitan France after 16 June 1940 and until the restoration of the Provisional Government of the French Republic. This nullification is hereby expressly declared and must be noted.

Article 3. The following acts are hereby expressly nullified and held invalid: The so-called "Constitutional Law of 10 July 1940; as well as any laws called 'Constitutional Law'; - Dompnier, Nathalie (2001). "Entre La Marseillaise et Maréchal, nous voilà! quel hymne pour le régime de Vichy ?". In Chimènes, Myriam (ed.). La vie musicale sous Vichy. Histoire du temps présent (in French). Bruxelles: Éditions Complexe – IRPMF-CNRS, coll. p. 71. ISBN 978-2-87027-864-2.

- "Henri-Philippe Pétain". History.com. 29 October 2009.

- Wilfred Byron Shaw (1940). Quarterly Review: A Journal of University Perspectives, Volumes 47-48. University of Michigan Libraries. p. 7 – via Google Books.

- Clayton Donnell (30 October 2017). The Battle for the Maginot Line, 1940. Pen and Sword. p. 129. ISBN 978-1473877306 – via Google Books.

- "Pétain of Verdun, of Vichy, of History". The New York Times. 15 November 1964. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Loi constitutionnelle du 10 juillet 1940 (Constitutional Law of 10 July 1940). "Fait à Vichy, le 10 juillet 1940 Par le président de la République, Albert Lebrun"

- Brian Jenkins; Chris Millington (2015). France and Fascism: February 1934 and the Dynamics of Political Crisis. Routledge. p. 149. ISBN 978-1317507253.

- Kocher, Matthew Adam; Lawrence, Adria K.; Monteiro, Nuno P. (1 November 2018). "Nationalism, Collaboration, and Resistance: France under Nazi Occupation". International Security. 43 (2): 117–150. doi:10.1162/isec_a_00329. ISSN 0162-2889. S2CID 57561272.

- Christopher Lloyd (2013). "Enduring Captivity: French POW Narratives of World War II". Journal of War & Culture Studies. 6 (1): 24–39. doi:10.1179/1752627212Z.0000000003. S2CID 159723385.

- Texte des actes constitutionnels de Vichy

- Cointet 2011, p. 38

- "Anciens sénateurs IIIème République : CHAUTEMPS Camille" (in French).

- Paul Webster (17 February 2011). "The Vichy Policy on Jewish Deportation". BBC. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Cointet 2011, p. 38.

- Cointet 1993, p. 228-249.

- Kupferman 2006, p. 269.

- Cointet 1993, p. 378-380

- Kupferman 2006, p. 383–388.

- Kupferman 2006, p. 383-388.

- Agnès Bruno, Florence Saint-Cyr-Gherardi, Nathalie Le Baut, Séverine Champonnois, Propagande contre propagande en France, 1939-1945, Musées des pays de l'Ain, 2006, 105 p., p. 56

- Cointet 1993, p. 393-394

- Raphaël Spina, "Impacts du STO sur le travail des entreprises", in Christian Chevandier and Jean-Claude Daumas, Actes du colloque Travailler dans les entreprises sous l'occupation, Presses universitaires de Franche-Comté, 2007

- Kupferman 2006, p. 413–416.

- H. Roderick Kedward, STO et Maquis, in Jean-Pierre Azéma and François Bédarida (eds.), La France des années noires, v. II, éditions du Seuil, 1993

- Kupferman 2006, p. 467-468

- Cointet 1993, p. 433-434,

- Kupferman 2006, p. 479-480

- Kupferman 2006, p. 492

- Kupferman 2006, p. 514-515

- H. Roderick Kedward, STO et Maquis, in Jean-Pierre Azéma and François Bédarida (edd.), La France des années noires (France in the Dark Years), v. II, éditions du Seuil, 1993.

- Cotillon 2009, p. 2, 16.

- Devers 2007.

- "Ministres de Vichy issus de l'Ecole Polytechnique" [Vichy Ministers who are alumni of the Ecole Polytechnique]. Association X-Resistance. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Jackson 2001, p. 175.

- Jean-Paul Cointet, Sigmaringen, op. cit., p. 53

- Robert Aron, Grands dossiers de l'histoire contemporaine, op. cit., p. 41–42.

- « Philippe Pétain (1856-1951) » [archive], at cheminsdememoire.gouv.fr.

- Robert Aron, Grands dossiers de l'histoire contemporaine, éd. Librairie académique Perrin, Paris, 1962-1964 ; rééd. CAL, Paris, chap. « Pétain : sa carrière, son procès », p. 41–45.

- Eberhard Jäckel, La France dans l'Europe de Hitler (France in Hitler's Europe), op. cit., p. 494–499 ; author notes p. 498–499 : "The maréchal wanted to surround this scene with a maximum of publicity and give it the character of a violent arrest. On the other hand he wanted to avoid bloodshed, so Neubronn was informed during the night through the Swiss minister [Walter Stucki], of what awaited the Germans the next morning. The entrances to the hôtel du Parc would be locked and barricaded, but the Maréchal's guards would not resist; the Germans were asked to obtain the necessary tools to force open the doors and gates. And this was done."

- Cotillon 2009 "By the conjunction of events precipitating a concentration of presidential and governmental powers in the hands of a single one, as in the case of the last President of the Council of the Republic also becoming the first head of the new French State, the person of Pétain finds himself at the same time invested with new executive functions without having been dispossessed of his former governmental attributions." See in particular note 42, p. 16. It is noted that although Laval as head of government does not bear the title of President of the Council, Pétain continues to hold the title and exercise the powers attached to it. Cf. on this subject AN 2AG 539 CC 140 B and Marc-Olivier Baruch, op cit p.|334-335 and 610.

- André Brissaud (preface Robert Aron), La Dernière année de Vichy (1943-1944) (The Last Year of Vichy), Paris, Librairie Académique Perrin, 1965, 587 p. (ASIN B0014YAW8Q), p. 504-505. The ministers were Jean Bichelonne, Abel Bonnard, Maurice Gabolde, Raymond Grasset et Paul Marion.

- Robert O. Paxton (trans. Claude Bertrand, preface. Stanley Hoffmann), La France de Vichy – 1940-1944, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, collection Points-Histoire, 1997 (reprint November 1999) (1st ed. 1973), 475 p. (ISBN 978-2-02-039210-5), p. 382-383

- Kupferman 2006, p. 520–525.

- André Brissaud, La Dernière année de Vichy (1943-1944), op. cit., p. 491-492

- Eberhard Jäckel (trad. fr German by Denise Meunier, pref. Alfred Grosser), La France dans l'Europe de Hitler ([« Frankreich in Hitlers Europa – Die deutsche Frankreichpolitik im Zweiten Weltkrieg »] France in Hitler's Europe), Paris, Fayard, collec. "Les grandes études contemporaines", 1968 (1st ed. Deutsche Verlag-Anstalg GmbH, Stuttgart, 1966), 554 p. (ASIN B0045C48VG), p. 495.

- Kupferman 2006, p. 527–529.

- Jäckel-fr 1968, p. 495.

- Aron 1962, p. 40,45.

- Aron 1962, p. 41-45.

- Aron 1962, p. 81–82.

- Sautermeister 2013, p. 13.

- Rousso 1999, p. 51–59.

- Béglé 2014.

- Jackson 2001, p. 567–568.

- Aron 1962, p. 48–49.

- Cointet 2014, p. 426.

- Robert Gildea, France since 1945 (1996) p 17

- Knox 1982, p. 152; Thompson & Adloff 1968, p. 21.

- Michael Robert Marrus; Robert O. Paxton (1995). Vichy France and the Jews. Stanford University Press. p. 191. ISBN 0804724997 – via Google Books.

- Playfair, I. S. O.; Molony, C. J. C.; Flynn, F. C. & Gleave, T. P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1966]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Destruction of the Axis Forces in Africa. History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. IV. Uckfield: Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-068-8.

- Jackson & Kitson 2020, p. 82.

- Keegan, John. Six Armies in Normandy. New York: Penguin Books, 1994. p300

- Sailendra Nath Sen (2012). Chandernagore: From Bondage to Freedom, 1900-1955. Primus Books. p. 43. ISBN 978-9380607238 – via Google Books.

- Paul R. Bartrop; Michael Dickerman, eds. (2017). The Holocaust: An Encyclopedia and Document Collection [4 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 321. ISBN 978-1440840845 – via Google Books.

- Salvatore Orlando, La presenza ed il ruolo della IV Armata italiana in Francia meridionale prima e dopo l’8 settembre 1943, Ufficio Storico dello Stato Maggiore dell’Esercito Italiano, Roma (in Italian)

- From the French Shoah memorial : Angelo Donati's report on the steps taken by the Italians to save the Jews in Italian-occupied France

- Robert O. Paxton (2001). Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order 1940-1944. Columbia University Press. p. 183. ISBN 0231124694. Retrieved 9 June 2020 – via Google Books.

- Italy and the Jews – Timeline by Elizabeth D. Malissa

- Paldiel, Mordecai (2000). Saving the Jews. Schreiber. ISBN 9781887563550. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- Jackson 2011, p. 68.

- Beigbeder 2006, p. 140.

- Kerem Bilgé (12 June 2019). "Admiral Leahy: U.S. Ambassador to Vichy".

- "France opens WW2 Vichy regime files". BBC News. 28 December 2015. Archived from the original on 9 November 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- Chirac, Jacques (16 July 1995). "Allocution de M. Jacques CHIRAC Président de la République prononcée lors des cérémonies commémorant la grande rafle des 16 et 17 juillet 1942 (Paris)" [Speech by M. Jacques CHIRAC President of the Republic delivered during the ceremonies commemorating the great round-up of 16 and 17 July 1942] (PDF). Avec le Président Chirac (in French). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Trials of War Criminals Before the Nuernberg Military Tribunals Under Control Council Law No. 10, Nuremberg, October 1946-April, 1949. Vol. 2 The Farben Case. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1949. p. 692. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

Works cited

- Aron, Robert (1962). "Pétain : sa carrière, son procès" [Pétain: his career, his trial]. Grands dossiers de l'histoire contemporaine [Major issues in contemporary history] (in French). Paris: Librairie Académique Perrin. OCLC 1356008.

- Béglé, Jérôme (20 January 2014). "Rentrée littéraire - Avec Pierre Assouline, Sigmaringen, c'est la vie de château !" [Autumn publishing season launch - With Pierre Assouline, Sigmaringen, That's life in the castle]. Le Point (in French). Le Point Communications.

- Beigbeder, Yves (29 August 2006). Judging War Crimes and Torture: French Justice and International Criminal Tribunals and Commissions (1940-2005). Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff/Brill. p. 140. ISBN 978-90-474-1070-6. OCLC 1058436580. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Cointet, Jean-Paul (1993). Pierre Laval. Paris: Arthème Fayard. ISBN 978-2-213-02841-5. OCLC 243773564.

- Cointet, Jean-Paul (2014). Sigmaringen. Tempus (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03300-2.

- Cointet, Michèle; Cointet, Jean-Paul (2000). Dictionnaire historique de la France sous l'Occupation [Historical dictionary of France under the Occupation] (in French) (2nd ed.). Tallandier. ISBN 978-2235-02234-7. OCLC 43706422.

- Cointet, Michèle (2011). Nouvelle histoire de Vichy (1940-1945) [New History of Vichy] (in French). Paris: Fayard. p. 797. ISBN 978-2-213-63553-8. OCLC 760147069.

- Cotillon, Jérôme (2009). "Les entourages de Philippe Pétain, chef de l'État français, 1940-1942" [The entourage of Philippe Pétain, French Head of State, 1940-1942] (PDF). Histoire@Politique – Politique, Culture, Société (pdf) (in French). 8 (8): 81. doi:10.3917/hp.008.0081.

- Devers, Gilles (1 November 2007). "Vichy 28. Loi du 12 juillet 1940 : composition du gouvernement" [Law of 12 July 1940: Composition of government]. avocats.fr. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Jäckel, Eberhard (1968) [1st pub. 1966: Deutsche Verlag-Anstalg GmbH (in German) as "Frankreich in Hitlers Europa – Die deutsche Frankreichpolitik im Zweiten Weltkrieg"]. La France dans l'Europe de Hitler [France in Hitler's Europe - Germany's France foreign policy in the Second World War]. Les grandes études contemporaines (in French). Paris: Fayard.

- Jackson, Julian (2001). France: The Dark Years, 1940–1944. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-820706-1.

- Jackson, Julian (15 October 2011). "7. The Republic and Vichy". In Edward G. Berenson; Vincent Duclert; Christophe Prochasson (eds.). The French Republic: History, Values, Debates. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Cornell University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-0801-46064-7. OCLC 940719314. Retrieved 20 July 2020.

- Jackson, Peter; Kitson, Simon (25 March 2020) [1st pub. Routledge (2007)]. "4. The paradoxes of Vichy foreign policy, 1940–1942". In Adelman, Jonathan (ed.). Hitler and His Allies in World War Two. Taylor & Francis. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-429-60389-1. OCLC 1146584068.

- Knox, MacGregor (1982). Mussolini Unleashed, 1939–1941: Politics and Strategy in Fascist Italy's Last War. Cambridge University Press.

- Kupferman, Fred (2006) [1st pub: Balland (1987)]. Laval (in French) (2 ed.). Paris: Tallandier. ISBN 978-2-84734-254-3.

- Rousso, Henry (1999). Pétain et la fin de la collaboration : Sigmaringen, 1944-1945 [Pétain and the end of collaboration: Sigmaringen, 1944-1945] (in French). Paris: Éditions Complexe. ISBN 2-87027-138-7.

- Sautermeister, Christine (6 February 2013). Louis-Ferdinand Céline à Sigmaringen : réalité et fiction dans "D'un château l'autre. Ecriture. ISBN 978-2-35905-098-1. OCLC 944523109. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

De septembre 1944 jusque fin avril 1945, Sigmaringen constitue donc une enclave française. Le drapeau français est hissé devant le château. Deux ambassades et un consulat en cautionnent la légitimité : l'Allemagne, le Japon et l'Italie.

- Thompson, Virginia McLean; Adloff, Richard (1968). Djibouti and the Horn of Africa. Stanford University Press.

- Vergez-Chaignon, Bénédicte (2014). Pétain (in French). Paris: Perrin. ISBN 978-2-262-03885-4. OCLC 896479806.

Further reading

- Diamond, Hanna, and Simon Kitson, eds. Vichy, Resistance, Liberation: New Perspectives On Wartime France (Bloomsbury, 2005).

- Gordon, Bertram M. Historical Dictionary of World War II France: The Occupation, Vichy, and the Resistance, 1938-1946 (1998).

- Jackson, Julian. France: The Dark Years, 1940-1944 (Oxford UP, 2004).

- Paxton, Robert. Vichy France: Old Guard, New Order, 1940-1944 (Knopf, 1972). online

.svg.png.webp)