Perry

Perry or pear cider is an alcoholic beverage made from fermented pears, traditionally in England, particularly Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire, parts of South Wales and France, especially Normandy and Anjou, Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Production

Fruit

Perry pears are thought to be descended from wild hybrids, known as wildings, between the cultivated pear Pyrus communis subsp. communis and the now-rare wild pear Pyrus communis subsp. pyraster.[1] The cultivated pear P. communis was brought to northern Europe by the Romans. In the fourth century CE Saint Jerome referred to perry as piracium.[2] Wild pear hybrids were, over time, selected locally for desirable qualities and by the 1800s, many regional varieties had been identified.[3]

.jpg.webp)

The majority of perry pear varieties in the UK originate from the counties of Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, and Worcestershire in the west of England; perry from these counties made from traditional recipes now forms a European Union Protected Geographical Indication. Of these perry pear varieties, most originate in parishes around May Hill on the Gloucestershire/Herefordshire border.[4] The standard reference work on perry pears was published in 1963 by the Long Ashton Research Station; since then, many varieties have become critically endangered or lost. Over 100 varieties, known by over 200 local names, were in Gloucestershire alone.[5] These local pears are particularly known for their picturesque names, such as the various "Huffcap" varieties ('Hendre Huffcap', 'Red Huffcap', 'Black Huffcap', all having an elliptical shape), those named for the effects of their product ('Merrylegs', 'Mumblehead'), pears commemorating an individual ('Stinking Bishop', named for the man who first grew it, or 'Judge Amphlett', named for Assizes court judge Richard Amphlett), or those named for the place they grew ('Hartpury Green', 'Bosbury Scarlet', 'Bartestree Squash'). The perry makers of Normandy grew their own distinctive varieties such as Plant de Blanc, Antricotin and Fausset; the perry of Domfront, which has been recognised with AOC status since 2002 and PDO status since 2006, must be made with a minimum of 40% Plant de Blanc.[6]

Pear cultivars used for perry-making tend to be small in size, turbinate or pyriform in shape, and too astringent for culinary use.[7] Specific perry pear cultivars are regularly used to make single-variety perries; this was formerly the usual practice in traditional perry making, meaning that in the past, each parish would have produced its own characteristic and distinctive perries due to the very restricted distribution of many varieties.[8] Blended perries, made from the juices of several varieties, were traditionally disregarded as they tended to throw a haze, though in modern commercial production, this is overcome with filtration and use of a centrifuge.

Good perry pears should have higher concentrations of tannins, acids, and other phenolic compounds.[3] Some of the pears considered to produce consistently excellent perry include the 'Barland', 'Brandy', 'Thorn,' and 'Yellow Huffcap' cultivars.[7] Compared to cider apples, perry pears have fewer volatile components and consequently fewer aromatics in the finished product.[9] Their tannin profile is very different from that of cider apples, with a predominance of astringent over bitter flavours. They do, however, contain a high concentration of deca-2,4-dienoate, a group of esters that affords them their prominent pear aroma.[9] Another important attribute of perry pears that distinguishes them from cider apples is their relatively higher content ratio of sorbitol to other sugars, such as fructose. Because sorbitol is not readily fermented by yeast, it is not converted to ethanol, so perry tends to have more residual sugar than cider produced from the fermentation of apples.[10] In addition to producing a sweeter beverage, sorbitol also contributes to increased body and a softer mouthfeel in the finished perry.[9] Compared to apples, pear pressing is made more difficult by the additional presence of specialized cells known as sclereids, which have thick cell walls that provide extra support and strength to the pear tissue.[11] Because of this inherent perry pear attribute, the addition of enzymes and pressing aids is a commonly used practice for improving perry production.[2]

| Type | Acidity % | Tannin % | Cultivars |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sweet | <0.3 | < 0.1 | Barnet, Red Pear |

| Medium Bittersharp | 0.3 - 0.45 | 0.1 - 0.2 | 'Blakeney Red', 'Gin' |

| Bittersharp | > 0.45 | < 0.2 | 'Butt', 'Barland' |

| Medium sharp | 0.3 - 0.45 | < 0.1 | 'Brandy', 'Hendre Huffcap' |

| Sharp | > 0.45 | < 0.1% | 'Yellow Huffcap' |

Orchard management and harvesting

.jpg.webp)

While cultivation of pears has been to some extent modernised, they remain a difficult crop to grow. Perry pear trees can live to a great age, and can be fully productive for 250 years. Pear trees, both domestic and perry varieties, grow incredibly slowly, taking up to, if not over, a decade before they bear enough fruit for harvest.[10] They also grow to a considerable height and can have very large canopies; the largest recorded, a tree at Holme Lacy, which still partly survives, covered three-quarters of an acre and yielded a crop of 5–7 tons in 1790.[14] Given the long maturing period of pear trees, they can be difficult to manage against diseases. Their size makes it difficult to apply pesticides, which makes preventing fire blight, a disease caused by the bacterium Erwinia amylovora that pears are even more susceptible to than cider apples, quite challenging.[2] These difficulties, along with demand for perry pears having (until recently) taken a decline, have prompted a national collection of perry pear cultivars to be gathered, housed, and cared for at the Three Counties Agricultural Showground at Malvern in Worcestershire, to maintain genetic resources,[9] which has now become the National Perry Pear Centre at Hartpury.[15] Similar germplasm repositories can be found at the National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Corvallis, Oregon.[16]

Also, key differences between cider and perry production exist in the harvesting and growing processes. Perry trees famously take more time to mature than cider trees. While cider trees may come to bear fruit in three to five years, traditionally managed perry trees typically take much longer, so much so that people say that one plants "pears for your heirs".[17]

Even when fully grown, pear trees bear less fruit than apples, which is one reason that perry is less common than cider.[18] When time to harvest comes, pears should be picked before they are ripe and then left to ripen indoors, while apples should be allowed to ripen on the tree.[19] Both apples and pears suffer from fire blight, which can devastate entire orchards, but pears are also susceptible to pear psylla (also known as Psylla pyri).[18] These insects kill the entire pear tree and are very resistant to insecticides, making them a severe problem for pear orchards.[20] Another added complication is that while apples are often harvested mechanically, pears must be harvested by hand, greatly increasing the time and cost of harvesting.[21]

Perry-making technique

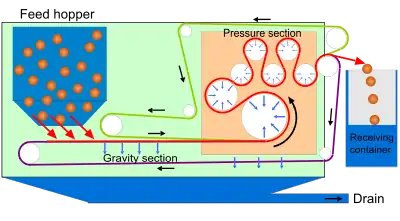

Traditional perry making is broadly similar to traditional cider making, in that the fruit is picked, crushed, and pressed to extract the juice, which is then fermented using the wild yeasts found on the fruit's skin. Traditional perry making employed querns and a rack and cloth press, in which the pulp is wrapped in cloth before being squeezed with a press.[22] Modern perry production can use a belt press, which is much more efficient for pressing fruit.[22] It works by sending the fruit down a conveyor belt, on which it is then pressed by rollers.[22] The principal differences between perry and cider production are that pears must be left for a period to mature after picking, and the pomace must be left to stand after initial crushing to lose tannins, a process analogous to wine maceration. [23] Additionally, because of the variation in hardness of the fruit, determining if a pear is ready for pressing than an apple can be more difficult.[24] Also, key chemical compositional differences occur between apples and pears; these factors play a crucial role in prefermentation and fermentation decisions for perry production.

Compared to most apples, pears tend to have more sugar and total phenolic compounds. The main sugars in perry pears are glucose (192 –284 mg/L), xylose (140–176 mg/g), and galacturonic acid (108–118 mg/g). Types of sugar that are present in the juice play an important role in yeast activity and determine the success of fermentation. Unlike the juice of apples, pear juice contains significant quantities of unfermentable sugar alcohols, particularly sorbitol.[25] The presence of sorbitol can give perry a residual sweetness, in addition to a mild laxative effect.[26] Pear juices contain rather low levels of amino acids, sources of nitrogen such as aspargine, aspartic acid and glutamic acid.[27]

After initial fermentation, many perries go through malolactic fermentation. On average, compared to apples, pears have higher levels of titrable acidity, most of it being citric acid. In environments with high levels of malic acid, such as grape must in winemaking, malolactic fermentation bacteria convert malic acid to lactic acid, reducing the perception of acidity and increasing complexity of flavour. However, if high levels of citric acid are present, as in pear pomace, malolactic fermentation bacteria catabolise citric acid to acetic acid and oxaloacetic acid, instead of lactic acid.[28] This results in a floral, citrus-like aroma in the final product, lacking the diacethyl odour typical for most products that have undergone a malolactic fermentation.

History

The earliest known reference to fermented alcoholic drinks being made from pears is found in Pliny.[29] Perry making seems to have become well established in what is today France following the collapse of the Roman empire; references to perry making in England do not appear before the Norman conquest. In the medieval period, France retained its association with pear growing, and the majority of pears consumed in England were in fact imported from France.[5]

By the 16th and 17th centuries, however, perry making had become well established in the west of England, where the climate and soil were especially suitable for pear cultivation. In the three counties of Worcestershire, Gloucestershire, and Herefordshire in particular, as well as in Monmouthshire across the Welsh border, perry pears grew well in conditions where cider apple trees would not. Smaller amounts were also produced in other cider-producing areas, such as Somerset. Perry may have grown in popularity after the English Civil War, when the large numbers of soldiers billeted in the Three Counties became acquainted with it,[30] and reached a zenith of popularity during the 18th century, when intermittent conflicts with France made the importing of wine difficult.[31] Many farms and estates had their own orchards, and many varieties of pears developed that were unique to particular parishes or villages.

Whereas perry in England remained an overwhelmingly dry, still drink served from the cask, Normandy perry (poiré) developed a bottle-fermented, sparkling style with a good deal of sweetness.[32]

Modern commercial perries

The production of traditional perry began to decline during the 20th century, in part due to changing farming practices– perry pears could be difficult and labour-intensive to crop, and orchards took many years to mature. The industry was, however, to a certain degree revived by modern commercial perry-making techniques, developed by Francis Showering of the firm Showerings of Shepton Mallet, Somerset, in the creation of their sparkling branded perry Babycham.[5] Babycham, the first mass-produced branded perry, was developed by Showering from application of the Long Ashton Institute's research, and was formerly produced from authentic perry pears, though today it is produced from concentrate, the firm's pear orchards having now been dug up.[14] Aimed at the female drinker at a time when wine was not commonly available in UK pubs, Babycham was sold in miniature Champagne-style bottles; the drink was for many years a strong seller and made a fortune for the Showering family.[33] A competing brand of commercial perry, Lambrini, is manufactured in Liverpool by Halewood International. The Irish drinks company Cantrell and Cochrane, Plc, more famous for its Magners and Bulmers ciders, launched a similar light perry, Ritz, in 1986.

Like commercial lager and commercial cider, commercial perry is highly standardised, and today often contains large quantities of cereal adjuncts such as corn syrup or invert sugar. It is also generally of lower strength, and sweeter, than traditional perry, and is artificially carbonated to give a sparkling finish. Unlike traditional perry, its manufacture guarantees a consistent product; the nature of perry pears means producing traditional perry in commercial quantities is very difficult. Traditional perry was overwhelmingly a drink made on farms for home consumption, or to sell in small quantities either at the farm gate or to local inns.

Decline and revival of traditional perry

Both English perry making and the orchards that supplied it suffered a catastrophic decline in the second half of the 20th century as a result of changing tastes and agricultural practices (in South Gloucestershire alone, an estimated 90% of orchards were lost in the last 75 years).[34] Many pear orchards were also lost to fire blight in the 1970s and 1980s. Along with the clearing of orchards, the decline of day labouring on farms meant that the manpower that was once devoted to harvest perry pears – as well as its traditional consumers – disappeared. It also lost popularity due to makers turning to dessert or general-purpose pears in its manufacture rather than perry pears, resulting in a thin and tasteless product.[5] In the UK, before 2007, the small amounts of traditional perry still produced were mainly consumed by people living in farming communities.

However, perry (often marketed under the name "pear cider", see below) has increased in popularity in very recent times, with around 2.5 million British consumers purchasing it in one year.[35] In addition, various organisations have been actively seeking out old perry pear trees and orchards and rediscovering lost varieties, many of which now exist only as single trees on isolated farms. For example, the Welsh Cider Society rediscovered the old Monmouthshire varieties 'Burgundy' and the 'Potato Pear', as well as a number of further types unrecorded up to that point.[36]

Naming controversy

Pear cider has been used as an alternative name for alcoholic drinks containing pear juice, in preference to the term perry.[37] The term has been dated to 1995, when Brothers Cider found that nobody at Glastonbury Festival understood what perry was; they began telling customers that it was 'like cider, but made from pears'.[38]

In the UK the new name has caused controversy. The Campaign for Real Ale (CAMRA) defines perry and pear cider as different drinks, stating that 'pear cider' as made by the large industrial cidermakers is a pear-flavoured drink, or more specifically a cider-style drink flavoured with pear concentrate, whereas 'perry' should be made by traditional methods from perry pears only.[39] The National Association of Cider Makers maintain that the terms perry and pear cider are interchangeable, and its rules specify that perry or pear cider may contain no more than 25% apple juice.[40][37][41]

See also

- Plum jerkum, a similar plum cider from Worcestershire

- Umeshu

- Framboise

- Poire Williams, a fruit brandy produced by distilling perry

References

- Cook, Gabe (25 September 2017). "The Ciderologist Speaks: In Praise of Perry".

- Merwin, Ian A.; Valois, Sarah; Padilla-Zakour, Olga I. (15 April 2008). Horticultural Reviews. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 365–415. doi:10.1002/9780470380147.ch6. ISBN 9780470380147.

- "Perry | Washington State University". cider.wsu.edu. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Gloucestershire Orchard Group, Pears Archived 25 August 2010 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 08-12-2009

- Pears and Perry Making in the UK Archived 18 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8 December 2009

- Le Poire Domfront, accessed 23-05-2018

- Postman, Joseph (April 2002). "Register of New Fruit and Nut Varieties: List 41" (PDF). HortScience. 37: 261–262.

- Luckwill and Billard (1963) Perry Pears: Produced as a Memorial to Professor B. T. P. Barker. Bristol: National Fruit and Cider Institute, p.27

- Jarvis, B. (1996). "Cider, perry, fruit wines and other alcoholic fruit beverages". Fruit Processing. Springer, Boston, MA. pp. 97–134. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-2103-7_5. ISBN 9781461358756.

- "Raise A Glass To Perry, Craft Cider's Pear Cousin". NPR.org. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- "Olympus FluoView Resource Center: Confocal Gallery - Pear Fruit Sclereids". fluoview.magnet.fsu.edu. Archived from the original on 18 May 2018. Retrieved 29 April 2018.

- Hort. Science, vol 9, october 1974, page 423

- HortScience, Vol. 37(2):251-272

- Oliver, T. The Three Counties & Welsh Marches Perry Presidium Protocol Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "National Perry Pear Centre - Conserving a part of our orchard heritage". National Perry Pear Centre. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "NCGR Corvallis Distribution Policies : USDA ARS". www.ars.usda.gov. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Ripe, Cherry (2009). "Perry" (PDF). Gastronomica. 9 (4): 58–61. doi:10.1525/gfc.2009.9.4.58. JSTOR 10.1525/gfc.2009.9.4.58.

- Robinson, Terrence. "High Density Pears: Profitable Not Just for You and your Heirs" (PDF). shaponline.org. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Hiller, Val (November 1997). "Harvesting Apples and Pears" (PDF). wsu.edu. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- "Pear psylla". jenny.tfrec.wsu.edu. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- Verma, M. K. (1 January 2014). Pear Production Technology. pp. 249–255. ISBN 9789383168095.

- Buglass, Alan J. (2011). Handbook of Alcoholic Beverages: Technical, Analytical and Nutritional Aspects. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-0-470-51202-9.

- Grafton, G. Perry Making Archived 7 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 8 December 2009

- "The Cider Workshop | Production | What's different about perry?". www.ciderworkshop.com. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Buglass, A. J. (2011). Cider and Perry. CH11: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 231–265.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Jolicoeur, C (2013). The New Cider Maker's Handbook. p. 155.

- Buglass, A. J. (2011). Cider and Perry. CH11: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. p. 237.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Yoshimi, Shimazu; Uehara, Mikio; Watanabe, Masazumi (1985). "Transformation of Citric Acid to Acetic Acid, Acetoin and Diacetyl by Wine Making Lactic Acid Bacteria". Agricultural and Biological Chemistry. 49 (7): 2147–2157. doi:10.1080/00021369.1985.10867041.

- "section XVI", Pliny's Natural History, vol. book XV, archived from the original on 1 January 2017, retrieved 28 October 2011

- Wilson, C. A. Liquid Nourishment: Potable foods and stimulating drinks, Edinburgh University Press, 1993, p.94

- Keeping It Real Archived 17 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Horticultural Society

- Normandy, World Perry Capital Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Welsh Perry & Cider Society, accessed 8 December 2009

- Prancing to the tune of Babycham, Daily Telegraph

- South Gloucestershire Council – Orchards Archived 4 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- "From perry to pear cider". BBC news magazine. 28 August 2009.

- Welsh Cider Society, accessed 8 December 2009 Archived 1 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Huddleston, Nigel (24 April 2008). "Pear Perception". Morning Advertiser. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- "From perry to pear cider". 28 August 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2022.

- "FAQs". CAMRA. Archived from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 25 July 2013.

- Pear cider ruling gives perry a timely boost, The Grocer, 19-05-2007

- "NACM Code of Practice". Archived from the original on 6 April 2010. Retrieved 9 December 2009.

External links

- Apple Cider and Perry Producers in UK

- Real Perry on the ukcider Wiki

- Out of the Pear Orchard and Into the Glass from National Public Radio

- Overview of making perry at home Archived 26 February 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- The Three Counties Cider and Perry Association

- The Holme Lacy Perry Pear Archived 22 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine, that in 1790 was recorded as producing 5–7 tons of fruit