Alcoholic beverage

An alcoholic beverage (also called an adult beverage, alcoholic drink, strong drink, or simply a drink) is a drink that contains ethanol, a type of alcohol that acts as a drug and is produced by fermentation of grains, fruits, or other sources of sugar.[2] The consumption of alcoholic drinks, often referred to as "drinking", plays an important social role in many cultures. Most countries have laws regulating the production, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages,[3] and the temperance movement advocates against the consumption of alcoholic beverages.[4] Regulations may require the labeling of the percentage alcohol content (as ABV or proof) and the use of a warning label. Some countries ban such activities entirely, but alcoholic drinks are legal in most parts of the world. The global alcoholic drink industry exceeded $1 trillion in 2018.[1]

Alcohol is a depressant, which in low doses causes euphoria, reduces anxiety, and increases sociability. In higher doses, it causes drunkenness, stupor, unconsciousness, or death. Long-term use can lead to an alcohol use disorder, an increased risk of developing several types of cancer, cardiovascular disease, and physical dependence.

According to the World Health Organization, alcohol is the highest risk-group carcinogen, and no quantity of its consumption can be considered safe.[5] According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dietary guidelines on alcohol, it is not recommended to start consuming alcohol for any reason; for those who drink, "drinking less is better for health than drinking more", and growing research indicates that even moderate drinking has no positive health benefits overall.[6] A systemic metanalysis of 107 cohort studies concluded low daily alcohol intake gives neither harm nor benefit; however, increased consumption, even at relatively low levels of daily intake (>2 beverages for women and >3 beverages for men), does increase health and mortality risks.[7]

Alcohol is one of the most widely used recreational drugs in the world, and about 33% of all humans currently drink alcohol.[8] In 2015, among Americans, 86% of adults had consumed alcohol at some point, with 70% drinking it in the last year and 56% in the last month.[9] Alcoholic drinks are typically divided into three classes—beers, wines, and spirits—and typically their alcohol content is between 3% and 50%.

Discovery of late Stone Age jugs suggest that intentionally fermented drinks existed at least as early as the Neolithic period (c. 10,000 BC).[10] Several other animals are affected by alcohol similarly to humans and, once they consume it, will consume it again if given the opportunity, though humans are the only species known to produce alcoholic drinks intentionally.[11]

Fermented drinks

Beer

Beer is a beverage fermented from grain mash. It is typically made from barley or a blend of several grains and flavored with hops. Most beer is naturally carbonated as part of the fermentation process. If the fermented mash is distilled, then the drink becomes a spirit. Beer is the most consumed alcoholic beverage in the world.[12]

Cider

Cider or cyder (/ˈsaɪdər/ SY-dər) is a fermented alcoholic drink made from any fruit juice; apple juice (traditional and most common), peaches, pears ("Perry" cider) or other fruit. Cider alcohol content varies from 1.2% ABV to 8.5% or more in traditional English ciders. In some regions, cider may be called "apple wine".[13]

Fermented tea

Fermented tea (also known as post-fermented tea or dark tea) is a class of tea that has undergone microbial fermentation, from several months to many years. The tea leaves and the liquor made from them become darker with oxidation. Thus, the various kinds of fermented teas produced across China are also referred to as dark tea, not be confused with black tea. The most famous fermented tea is kombucha which is often homebrewed, pu-erh, produced in Yunnan Province,[14][15] and the Anhua dark tea produced in Anhua County of Hunan Province. The majority of kombucha on the market are under 0.5% ABV.

Fermented water

Fermented water is an ethanol-based water solution with approximately 15-17% ABV without sweet reserve. Fermented water is exclusively fermented with white sugar, yeast, and water. Fermented water is clarified after the fermentation to produce a colorless or off-white liquid with no discernible taste other than that of ethanol.

Fermented sugar water

Fermented sugar water is fermented water with added refined sugar.

Mead

Mead (/miːd/) is an alcoholic drink made by fermenting honey with water, sometimes with various fruits, spices, grains, or hops. The alcoholic content of mead may range from as low as 3% ABV to more than 20%. The defining characteristic of mead is that the majority of the drink's fermentable sugar is derived from honey. Mead can also be referred to as "honeywine."

Pulque

Pulque is the Mesoamerican fermented drink made from the "honey water" of maguey, Agave americana. Pulque can be distilled to produce tequila or mescal Mezcal.[16]

Wine

Wine is a fermented beverage most commonly produced from grapes. Wine involves a longer fermentation process than beer and often a long aging process (months or years), resulting in an alcohol content of 9%–16% ABV.

Sparkling wines such French Champagne, Catalan Cava or Italian Prosecco are also made from grapes, with a secondary fermentation.

Fruit wines are made from fruits other than grapes, such as plums, cherries, or apples.

Distilled beverages

Distilled beverages (also called liquors or spirit drinks) are alcoholic drinks produced by distilling (i.e., concentrating by distillation) ethanol produced by means of fermenting grain, fruit, or vegetables.[17] Unsweetened, distilled, alcoholic drinks that have an alcohol content of at least 20% ABV are called spirits.[18] For the most common distilled drinks, such as whiskey and vodka, the alcohol content is around 40%. The term hard liquor is used in North America to distinguish distilled drinks from undistilled ones (implicitly weaker). Vodka, gin, baijiu, shōchū, soju, tequila, whiskey, brandy and rum are examples of distilled drinks. Distilling concentrates the alcohol and eliminates some of the congeners. Freeze distillation concentrates ethanol along with methanol and fusel alcohols (fermentation by-products partially removed by distillation) in applejack.

Fortified wine is wine, such as port or sherry, to which a distilled beverage (usually brandy) has been added.[19] Fortified wine is distinguished from spirits made from wine in that spirits are produced by means of distillation, while fortified wine is wine that has had a spirit added to it. Many different styles of fortified wine have been developed, including port, sherry, madeira, marsala, commandaria, and the aromatized wine vermouth.[20]

Rectified spirit

Rectified spirit, also called "neutral grain spirit", is alcohol which has been purified by means of "rectification" (i.e. repeated distillation). The term neutral refers to the spirit's lack of flavor that would have been present if the mash ingredients had been distilled to a lower level of alcoholic purity. Rectified spirit also lacks any flavoring added to it after distillation (as is done, for example, with gin). Other kinds of spirits, such as whiskey, are distilled to a lower alcohol percentage to preserve the flavor of the mash.

Rectified spirit is a clear, colorless, flammable liquid that may contain as much as 95% ABV. It is often used for medicinal purposes. It may be a grain spirit or it may be made from other plants. It is used in mixed drinks, liqueurs, and tinctures, and also as a household solvent.

Congeners

In the alcoholic drinks industry, congeners are substances produced during fermentation. These substances include small amounts of chemicals such as occasionally desired other alcohols, like propanol and 3-methyl-1-butanol, but also compounds that are never desired such as acetone, acetaldehyde and glycols. Congeners are responsible for most of the taste and aroma of distilled alcoholic drinks, and contribute to the taste of non-distilled drinks.[21] It has been suggested that these substances contribute to the symptoms of a hangover.[22] Tannins are congeners found in wine in the presence of phenolic compounds. Wine tannins add bitterness, have a drying sensation, taste herbaceous, and are often described as astringent. Wine tannins adds balance, complexity, structure and makes a wine last longer, so they play an important role in the aging of wine.[23]

Amount of use

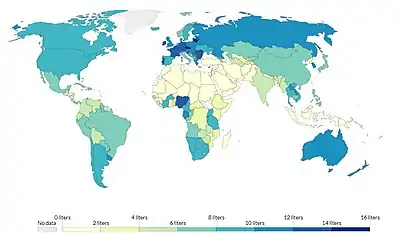

The average number of people who drink as of 2016 was 39% for males and 25% for females (2.4 billion people in total).[8] Females on average drink 0.7 drinks per day while males drink 1.7 drinks per day.[8] The rates of drinking varies significantly in different areas of the world.[8]

Reasons for use

Apéritifs and digestifs

An apéritif is any alcoholic beverage usually served before a meal to stimulate the appetite,[25] while a digestif is any alcoholic beverage served after a meal for the stated purpose of improving digestion. Fortified wine, liqueurs, and dry champagne are common apéritifs. Because apéritifs are served before dining, they are usually dry rather than sweet. One example is Cinzano, a brand of vermouth. Digestifs include brandy, fortified wines and herb-infused spirits (Drambuie).

Caloric content

The USDA uses a figure of 6.93 kilocalories (29.0 kJ) per gram of alcohol (5.47 kcal or 22.9 kJ per ml) for calculating food energy.[26] For distilled spirits, a standard serving in the United States is 44 ml (1.5 US fl oz), which at 40% ethanol (80 proof), would be 14 grams and 98 calories. For other than distilled spirits, many alcoholic drinks contain carbohydrates, which adds to the calories per serving.

Alcoholic drinks are considered empty calorie foods because other than food energy they contribute no essential nutrients. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, based on NHANES 2013–2014 surveys, women in the US ages 20 and up consume on average 6.8 grams/day and men consume on average 15.5 grams/day.[27]

Alcohol is known to potentiate the insulin response of the human body to glucose, which, in essence, "instructs" the body to convert consumed carbohydrates into fat and to suppress carbohydrate and fat oxidation.[28][29] Ethanol is directly processed in the liver to acetyl CoA, the same intermediate product as in glucose metabolism. Because ethanol is mostly metabolized and consumed by the liver, chronic excessive use can lead to fatty liver. This leads to a chronic inflammation of the liver and eventually alcoholic liver disease.

Flavoring

Pure ethanol tastes bitter to humans; some people also describe it as sweet.[30] However, ethanol is also a moderately good solvent for many fatty substances and essential oils. This facilitates the use of flavoring and coloring compounds in alcoholic drinks as a taste mask, especially in distilled drinks. Some flavors may be naturally present in the beverage's raw material. Beer and wine may also be flavored before fermentation, and spirits may be flavored before, during, or after distillation. Sometimes flavor is obtained by allowing the beverage to stand for months or years in oak barrels, usually made of American or French oak. A few brands of spirits may also have fruit or herbs inserted into the bottle at the time of bottling.

Wine is important in cuisine not just for its value as an accompanying beverage, but as a flavor agent, primarily in stocks and braising, since its acidity lends balance to rich savory or sweet dishes.[31] Wine sauce is an example of a culinary sauce that uses wine as a primary ingredient.[32] Natural wines may exhibit a broad range of alcohol content, from below 9% to above 16% ABV, with most wines being in the 12.5–14.5% range.[33] Fortified wines (usually with brandy) may contain 20% alcohol or more.

Alcohol measurement

Alcohol concentration

| Fruit juices | < 0.1% |

| Cider, wine coolers | 4%–8% |

| Beers | typically 5% (range is from 3–15%) |

| Wines | typically 13.5% (range is from 8%–17%) |

| Sakes | 15–16% |

| Fortified wines | 15–22% |

| Spirits | typically 30%-40% (range is from 15% to, in some rare cases, up to 98%) |

The concentration of alcohol in a beverage is usually stated as the percentage of alcohol by volume (ABV, the number of milliliters (ml) of pure ethanol in 100 ml of beverage) or as proof. In the United States, proof is twice the percentage of alcohol by volume at 60 degrees Fahrenheit (e.g. 80 proof = 40% ABV). Degrees proof were formerly used in the United Kingdom, where 100 degrees proof was equivalent to 57.1% ABV. Historically, this was the most dilute spirit that would sustain the combustion of gunpowder.

Ordinary distillation cannot produce alcohol of more than 95.6% by weight, which is about 97.2% ABV (194.4 proof) because at that point alcohol is an azeotrope with water. A spirit which contains a very high level of alcohol and does not contain any added flavoring is commonly called a neutral spirit. Generally, any distilled alcoholic beverage of 170 US proof or higher is considered to be a neutral spirit.[35]

Most yeasts cannot reproduce when the concentration of alcohol is higher than about 18%, so that is the practical limit for the strength of fermented drinks such as wine, beer, and sake. However, some strains of yeast have been developed that can reproduce in solutions of up to 25% ABV.[36]

Serving measures

Shot sizes

Shot sizes vary significantly from country to country. In the United Kingdom, serving size in licensed premises is regulated under the Weights and Measures Act (1985). A single serving size of spirits (gin, whisky, rum, and vodka) are sold in 25 ml or 35 ml quantities or multiples thereof.[37] Beer is typically served in pints (568 ml), but is also served in half-pints or third-pints. In Israel, a single serving size of spirits is about twice as much, 50 or 60 mL.

The shape of a glass can have a significant effect on how much one pours. A Cornell University study of students and bartenders' pouring showed both groups pour more into short, wide glasses than into tall, slender glasses.[38] Aiming to pour one shot of alcohol (1.5 ounces or 44.3 ml), students on average poured 45.5 ml & 59.6 ml (30% more) respectively into the tall and short glasses. The bartenders scored similarly, on average pouring 20.5% more into the short glasses. More experienced bartenders were more accurate, pouring 10.3% less alcohol than less experienced bartenders. Practice reduced the tendency of both groups to over pour for tall, slender glasses but not for short, wide glasses. These misperceptions are attributed to two perceptual biases: (1) Estimating that tall, slender glasses have more volume than shorter, wider glasses; and (2) Over focusing on the height of the liquid and disregarding the width.

Standard drinks

There is no single standard, but a standard drink of 10g alcohol, which is used in the WHO AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test)'s questionnaire form example,[39] have been adopted by more countries than any other amount.[40] 10 grams is equivalent to 12.7 millilitres.

A standard drink is a notional drink that contains a specified amount of pure alcohol. The standard drink is used in many countries to quantify alcohol intake. It is usually expressed as a measure of beer, wine, or spirits. One standard drink always contains the same amount of alcohol regardless of serving size or the type of alcoholic beverage. The standard drink varies significantly from country to country. For example, it is 7.62 ml (6 grams) of alcohol in Austria, but in Japan it is 25 ml (19.75 grams).

- In the United Kingdom, there is a system of units of alcohol which serves as a guideline for alcohol consumption. A single unit of alcohol is defined as 10 ml. The number of units present in a typical drink is sometimes printed on bottles. The system is intended as an aid to people who are regulating the amount of alcohol they drink; it is not used to determine serving sizes.

- In the United States, the standard drink contains 0.6 US fluid ounces (18 ml) of alcohol. This is approximately the amount of alcohol in a 12-US-fluid-ounce (350 ml) glass of beer, a 5-US-fluid-ounce (150 ml) glass of wine, or a 1.5-US-fluid-ounce (44 ml) glass of a 40% ABV (80 US proof) spirit.

Laws

Alcohol laws regulate the manufacture, packaging, labelling, distribution, sale, consumption, blood alcohol content of motor vehicle drivers, open containers, and transportation of alcoholic drinks. Such laws generally seek to reduce the adverse health and social impacts of alcohol consumption. In particular, alcohol laws set the legal drinking age, which usually varies between 15 and 21 years old, sometimes depending upon the type of alcoholic drink (e.g., beer vs wine vs hard liquor or distillates). Some countries do not have a legal drinking or purchasing age, but most countries set the minimum age at 18 years.[3]

Some countries, such as the U.S., have the drinking age higher than the legal age of majority (18), at age 21 in all 50 states. Such laws may take the form of permitting distribution only to licensed stores, monopoly stores, or pubs and they are often combined with taxation, which serves to reduce the demand for alcohol (by raising its price) and it is a form of revenue for governments. These laws also often limit the hours or days (e.g., "blue laws") on which alcohol may be sold or served, as can also be seen in the "last call" ritual in US and Canadian bars, where bartenders and servers ask patrons to place their last orders for alcohol, due to serving hour cutoff laws. In some countries, alcohol cannot be sold to a person who is already intoxicated. Alcohol laws in many countries prohibit drunk driving.

In some jurisdictions, alcoholic drinks are totally prohibited for reasons of religion (e.g., Islamic countries with sharia law) or for reasons of local option, public health, and morals (e.g., Prohibition in the United States from 1920 to 1933). In jurisdictions which enforce sharia law, the consumption of alcoholic drinks is an illegal offense,[41] although such laws may exempt non-Muslims.[42]

Alcohol and health

Light and moderate alcohol consumption increases cancer risk in individuals, especially with respect to squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, oropharyngeal cancer, and breast cancer.[43][44]

Some nations have introduced alcohol packaging warning messages that inform consumers about alcohol and cancer, as well as foetal alcohol syndrome.[45] The addition of warning labels on alcoholic beverages is historically supported by organizations of the temperance movement, such as the Woman's Christian Temperance Union, as well as by medical organisations, such as the Irish Cancer Society.[46][47]

History

- 10,000–5000 BC: Discovery of late Stone Age jugs suggests that intentionally fermented drinks existed at least as early as the Neolithic period.[48]

- 7000–5600 BC: Examination and analysis of ancient pottery jars from the neolithic village of Jiahu in the Henan province of northern China revealed residue left behind by the alcoholic drinks they had once contained. According to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, chemical analysis of the residue confirmed that a fermented drink made of grape and hawthorn fruit wine, honey mead and rice beer was being produced in 7000–5600 BC (McGovern et al., 2005; McGovern 2009).[49][50] The results of this analysis were published in December 2004.[51]

- 9th–10th centuries AD: Medieval Muslim chemists such as Jābir ibn Ḥayyān (Latin: Geber, ninth century) and Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (Latin: Rhazes, c. 865–925) experimented extensively with the distillation of various substances. The distillation of wine is attested in Arabic works attributed to al-Kindī (c. 801–873 CE) and to al-Fārābī (c. 872–950), and in the 28th book of al-Zahrāwī's (Latin: Abulcasis, 936–1013) Kitāb al-Taṣrīf (later translated into Latin as Liber servatoris).[52]

- 12th century: The process of distillation spread from the Middle East to Italy,[53] where distilled alcoholic drinks were recorded in the mid-12th century.[54] In China, archaeological evidence indicates that the true distillation of alcohol began during the 12th century Jin or Southern Song dynasties.[55] A still has been found at an archaeological site in Qinglong, Hebei, dating to the 12th century.[55]

- 14th century: In India, the true distillation of alcohol was introduced from the Middle East, and was in wide use in the Delhi Sultanate by the 14th century.[53] By the early 14th century, distilled alcoholic drinks had spread throughout the European continent.[54]

See also

References

- "Worldwide Alcohol Consumption Declines -1.6%". International Wines and Spirits Record (ISWR). 2019-05-30. Archived from the original on 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- Cook, Christopher C. H. (4 May 2006). Alcohol, Addiction and Christian Ethics. Cambridge University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-139-45497-1.

'Drunkenness', at least in popular usage, he considered to be equivalent to 'intoxication'. Intoxication in turn, again according to popular usage, was understood as referring to 'the aggravated symptoms of alcoholic poisoning'. While recognising that intemperance was, in fact, 'indicative of sensual indulgence in general', he stated that in 'popular usage' it had gradually become narrowed in meaning to 'indulgence of the appetite for Strong Drink' or 'indulgence in some alcoholic drink'.

- "Minimum Legal Age Limits". IARD.org. International Alliance for Responsible Drinking. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- Henry, Yeomans (18 June 2014). Alcohol and Moral Regulation: Public Attitudes, Spirited Measures and Victorian Hangovers. Policy Press. p. 244. ISBN 978-1-4473-0994-9.

- "No level of alcohol consumption is safe for our health". www.who.int. Archived from the original on 2023-01-12. Retrieved 2023-01-12.

- "Dietary Guidelines for Alcohol - Facts about Moderate Drinking". www.cdc.gov. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 25 July 2022.

- Bisognano, John (April 5, 2023). "Daily Alcohol Intake and Risk of All-Cause Mortality". American College of Cardiology.

- Griswold, Max G.; Fullman, Nancy; Hawley, Caitlin; Arian, Nicholas; Zimsen, Stephanie R M.; Tymeson, Hayley D.; Venkateswaran, Vidhya; Tapp, Austin Douglas; Forouzanfar, Mohammad H.; Salama, Joseph S.; Abate, Kalkidan Hassen; Abate, Degu; Abay, Solomon M.; Abbafati, Cristiana; Abdulkader, Rizwan Suliankatchi; Abebe, Zegeye; Aboyans, Victor; Abrar, Mohammed Mehdi; Acharya, Pawan; Adetokunboh, Olatunji O.; Adhikari, Tara Ballav; Adsuar, Jose C.; Afarideh, Mohsen; Agardh, Emilie Elisabet; Agarwal, Gina; Aghayan, Sargis Aghasi; Agrawal, Sutapa; Ahmed, Muktar Beshir; Akibu, Mohammed; et al. (August 2018). "Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016". The Lancet. 392 (10152): 1015–35. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31310-2. PMC 6148333. PMID 30146330.

- "Alcohol Facts and Statistics". National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. National Institute of Health. August 2018. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Charles H, Patrick; Durham, NC (1952). Alcohol, Culture, and Society. Duke University Press (reprint edition by AMS Press, New York, 1970). pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-404-04906-5.

- Zielinski, Sarah (16 September 2011). "The Alcoholics of the Animal World". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on 22 August 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

- Nelson, Max (2005). The Barbarian's Beverage: A History of Beer in Ancient Europe. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-415-31121-2. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 21 September 2010.

- Martin Dworkin, Stanley Falkow (2006). The Prokaryotes: Proteobacteria: alpha and beta subclasses. Springer. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-387-25495-1. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

- Mo, Haizhen, Yang Zhu, and Zongmao Chen. "Microbial fermented tea–a potential source of natural food preservatives." Trends in food science & technology 19.3 (2008): 124-130.

- Lv, Hai-peng, et al. "Processing and chemical constituents of Pu-erh tea: A review." Food Research International 53.2 (2013): 608-618.

- Super, "Alcoholic Beverages", pp. 45–46.

- "Distilled spirit/distilled liquor". Britannica.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- Lichine, Alexis. Alexis Lichine's New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th edition) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 707–709.

- Lichine, Alexis (1987). Alexis Lichine's New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 236. ISBN 978-0-394-56262-9.

- Robinson, J., ed. (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3rd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 978-0-19-860990-2.

- Understanding Congeners in Wine Archived 2013-06-13 at the Wayback Machine, Wines & Vines. Accessed 2011-4-20

- Whisky hangover 'worse than vodka, a study suggests' Archived 2023-01-23 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News. Accessed 2009-12-19

- "The 5 Basic Wine Characteristics". Wine Folly. 2012-07-23. Archived from the original on 2015-03-15. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Alcohol consumption per person". Our World in Data. Archived from the original on 16 March 2020. Retrieved 15 February 2020.

- Caton, S.J.; Ball, M; Ahern, A; Hetherington, M.M. (2004). "Dose-dependent effects of alcohol on appetite and food intake". Physiology & Behavior. 81 (1): 51–58. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2003.12.017. PMID 15059684. S2CID 22424908.

- "Composition of Foods Raw, Processed, Prepared USDA National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 26 Documentation and User Guide" (PDF). USDA. August 2013. p. 14. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-09-25. Retrieved 2014-02-03.

- "What We Eat in America, NHANES 2013-2014" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-24. Retrieved 2021-09-29.

- Robert Metz; et al. (1969). "Potentiation of the Plasma Insulin Response to Glucose by Prior Administration of Alcohol" (PDF). Diabetes. 18 (8): 517–22. doi:10.2337/diab.18.8.517. PMID 4897290. S2CID 32072796. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-02-22. Retrieved 2014-02-11.

- Shelmet, JJ; Reichard, GA; Skutches, CL; Hoeldtke, RD; Owen, OE; Boden, G (1988). "Ethanol Causes Acute Inhibition of Carbohydrate, Fat, and Protein Oxidation and Insulin Resistance". J. Clin. Invest. 81 (4): 1137–45. doi:10.1172/JCI113428. PMC 329642. PMID 3280601.

- Scinska, A; Koros, E; Habrat, B; Kukwa, A; Kostowski, W; Bienkowski, P (2000). "Bitter and sweet components of ethanol taste in humans". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 60 (2): 199–206. doi:10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00149-0. PMID 10940547.

- "6 Secrets of Cooking with Wine". Archived from the original on 2017-03-22. Retrieved 2017-04-12.

- Parker, Robert M. (2008). Parker's Wine Buyer's Guide, 7th Edition. Simon and Schuster. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-4391-3997-4.

- Jancis Robinson (2006). The Oxford Companion to Wine (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860990-2. See alcoholic strength at p. 10.

- "Find the Alcohol Contents of Beer, Wine, and Liquor". Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- Lichine, Alexis. Alexis Lichine's New Encyclopedia of Wines & Spirits (5th edition) (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987), 365.

- Stewart, Graham G. "Biographical Review: Seduced by Yeast". Journal of the American Society of Brewing Chemists (2015): 1–21. American Society of Brewing Chemists. 21 Jan. 2015. Web. 14 May 2017.

- "fifedirect – Licensing & Regulations – Calling Time on Short Measures!". Fifefire.gov.uk. 2008-07-29. Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2010-02-11.

- Wansink, Brian; van Ittersum, Koert (2005). "Shape of glass and amount of alcohol poured: comparative study of effect of practice and concentration". BMJ. 331 (7531): 1512–14. doi:10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1512. PMC 1322248. PMID 16373735.

- "AUDIT The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (Second Edition)" (pdf). WHO. 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-20. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- Kalinowski, A.; Humphreys, K. (2016-04-13). "Governmental standard drink definitions and low‐risk alcohol consumption guidelines in 37 countries". Addiction. 111 (7): 1293–8. doi:10.1111/add.13341. PMID 27073140.

- Williams, Lizzie. Nigeria: The Bradt Travel Guide. p. 101.

- Alcohol and Temperance in Modern History p. 329 David M. Fahey, Ian R. Tyrrell (2003)

- Cheryl Platzman Weinstock (8 November 2017). "Alcohol Consumption Increases Risk of Breast and Other Cancers, Doctors Say". Scientific American. Archived from the original on 28 November 2020. Retrieved 13 November 2018.

The ASCO statement, published in the Journal of Clinical Oncology, cautions that while the greatest risks are seen with heavy long-term use, even low alcohol consumption (defined as less than one drink per day) or moderate consumption (up to two drinks per day for men, and one drink per day for women because they absorb and metabolize it differently) can increase cancer risk. Among women, light drinkers have a four percent increased risk of breast cancer, while moderate drinkers have a 23 percent increased risk of the disease.

- LoConte, Noelle K.; Brewster, Abenaa M.; Kaur, Judith S.; Merrill, Janette K.; Alberg, Anthony J. (7 November 2017). "Alcohol and Cancer: A Statement of the American Society of Clinical Oncology". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 36 (1): 83–93. doi:10.1200/JCO.2017.76.1155. PMID 29112463.

Clearly, the greatest cancer risks are concentrated in the heavy and moderate drinker categories. Nevertheless, some cancer risk persists even at low levels of consumption. A meta-analysis that focused solely on cancer risks associated with drinking one drink or fewer per day observed that this level of alcohol consumption was still associated with some elevated risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus (sRR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.09 to 1.56), oropharyngeal cancer (sRR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.29), and breast cancer (sRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.08), but no discernable associations were seen for cancers of the colorectum, larynx, and liver.

- "Cancer warning labels to be included on alcohol in Ireland, minister confirms". Belfast Telegraph. 26 September 2018. Archived from the original on 11 April 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- Chandler, Ellen (2012). "FASD - Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder". White Ribbon Signal. 117 (2): 2.

- Finn, Christina. "Irish Cancer Society urges minister not to drop proposed cancer warning labels on alcohol products". TheJournal.ie. Archived from the original on 2023-02-20. Retrieved 2023-02-20.

- Patrick, Clarence Hodges (1952). Alcohol, Culture, and Society. Durham, NC: Duke University Press (reprint edition by AMS Press, New York, 1970). pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-404-04906-5.

- Chrzan, Janet (2013). Alcohol: Social Drinking in Cultural Context. Routledge. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-415-89249-0.

- McGovern, P.E.; Zhang, J.; Tang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Hall, G.R.; Moreau, R.A.; Nunez, A.; Butrym, E.D.; Richards, M.P.; Wang, C.-S.; Cheng, G.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, C. (2004). "Fermented beverages of pre- and proto-historic China". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (51): 17593–98. Bibcode:2004PNAS..10117593M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. PMC 539767. PMID 15590771.

- Roach, John. "Cheers! Eight ancient drinks uncorked by science". Nbc News. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 9 June 2013.

- al-Hassan, Ahmad Y. (2009). "Alcohol and the Distillation of Wine in Arabic Sources from the 8th Century". Studies in al-Kimya': Critical Issues in Latin and Arabic Alchemy and Chemistry. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag. pp. 283–298. (same content also available on the author's website Archived 2015-12-29 at the Wayback Machine); cf. Berthelot, Marcellin; Houdas, Octave V. (1893). La Chimie au Moyen Âge. Vol. I–III. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. vol. I, pp. 141, 143.

- Irfan Habib (2011), Economic History of Medieval India, 1200–1500, p. 55, Pearson Education

- Forbes, Robert James (1970). A Short History of the Art of Distillation: From the Beginnings up to the Death of Cellier Blumenthal. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-00617-1. Archived from the original on 23 January 2023. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- Haw, Stephen G. (2006). "Wine, women and poison". Marco Polo in China. Routledge. pp. 147–48. ISBN 978-1-134-27542-7. Retrieved 2016-07-10.

The earliest possible period seems to be the Eastern Han dynasty... the most likely period for the beginning of true distillation of spirits for drinking in China is during the Jin and Southern Song dynasties

External links

- "Even a Little Alcohol Can Harm Your Health" (The New York Times; 2023-01-13) at Archive.Today – Related JAMA Study (archive)

- "What Is a Standard Drink?" (NIH / National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2023) at Archive.Today (archive)

- "About 37 percent of college students could now be considered alcoholics", (Daily Emerald; 2018-11-05) (archive)