Pollard script

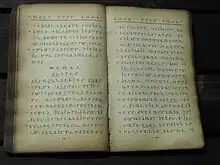

The Pollard script, also known as Pollard Miao (Chinese: 柏格理苗文; pinyin: Bó Gélǐ Miáo-wén) or Miao, is an abugida loosely based on the Latin alphabet and invented by Methodist missionary Sam Pollard. Pollard invented the script for use with A-Hmao, one of several Miao languages spoken in southeast Asia. The script underwent a series of revisions until 1936, when a translation of the New Testament was published using it.

| Pollard Pollard Miao | |

|---|---|

| |

| Script type | |

| Creator | Sam Pollard |

Time period | ca. 1936 to the present |

| Direction | left-to-right |

| Languages | A-Hmao, Lipo, Sichuan Miao, Nasu |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | Canadian Aboriginal syllabics

|

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Plrd (282), Miao (Pollard) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Miao |

| U+16F00–U+16F9F | |

Pollard credited the basic idea of the script to the Cree syllabics designed by James Evans in 1838–1841: “While working out the problem, we remembered the case of the syllabics used by a Methodist missionary among the Indians of North America, and resolved to do as he had done.” He also gave credit to a Chinese pastor: “Stephen Lee assisted me very ably in this matter, and at last we arrived at a system.”[1]

The introduction of Christian materials in the script that Pollard invented had a great impact among the Miao people. Part of the reason was that they had a legend about how their ancestors had possessed a script but lost it. According to the legend, the script would be brought back some day. When the script was introduced, many Miao came from far away to see and learn it.[2][3] Changing politics in China led to the use of several competing scripts, most of which were romanizations. The Pollard script remains popular among Hmong people in China, although Hmong outside China tend to use one of the alternative scripts. A revision of the script was completed in 1988, which remains in use.

As with most other abugidas, the Pollard letters represent consonants, whereas vowels are indicated by diacritics. Uniquely, however, the position of this diacritic is varied to represent tone. For example, in Western Hmong, placing the vowel diacritic above the consonant letter indicates that the syllable has a high tone, whereas placing it at the bottom right indicates a low tone.

Alphabets

The script was originally developed for A-Hmao, and adopted early for Lipo. In 1949 Pollard adapted it for a group of Miao in Szechuan, creating a distinct alphabet.[4] There is also a Nasu alphabet using Pollard script.

Consonants

| 𖼀 | 𖼁 | 𖼂 | 𖼃 | 𖼄 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PA | BA | YI PA | PLA | MA |

| 𖼅 | 𖼆 | 𖼇 | 𖼈 | 𖼉 |

| MHA | ARCHAIC MA | FA | VA | VFA |

| 𖼊 | 𖼋 | 𖼌 | 𖼍 | 𖼎 |

| TA | DA | YI TTA | YI TA | TTA |

| 𖼏 | 𖼐 | 𖼑 | 𖼒 | 𖼓 |

| DDA | NA | NHA | YI NNA | ARCHAIC NA |

| 𖼔 | 𖼕 | 𖼖 | 𖼗 | 𖼘 |

| NNA | NNHA | LA | LYA | LHA |

| 𖼙 | 𖼚 | 𖼛 | 𖼜 | 𖼝 |

| LHYA | TLHA | DLHA | TLHYA | DLHYA |

| 𖼞 | 𖼟 | 𖼠 | 𖼡 | 𖼢 |

| KA | GA | YI KA | QA | QGA |

| 𖼣 | 𖼤 | 𖼥 | 𖼦 | 𖼧 |

| NGA | NGHA | ARCHAIC NGA | HA | XA |

| 𖼨 | 𖼩 | 𖼪 | 𖼫 | 𖼬 |

| GHA | GHHA | TSSA | DZZA | NYA |

| 𖼭 | 𖼮 | 𖼯 | 𖼰 | 𖼱 |

| NYHA | TSHA | DZHA | YI TSHA | YI DZHA |

| 𖼲 | 𖼳 | 𖼴 | 𖼵 | 𖼶 |

| REFORMED TSHA | SHA | SSA | ZHA | ZSHA |

| 𖼷 | 𖼸 | 𖼹 | 𖼺 | 𖼻 |

| TSA | DZA | YI TSA | SA | ZA |

| 𖼼 | 𖼽 | 𖼾 | 𖼿 | 𖽀 |

| ZSA | ZZA | ZZSA | ZZA | ZZYA |

| 𖽁 | 𖽂 | 𖽃 | 𖽄 | 𖽅 |

| ZZSYA | WA | AH | HHA | BRI |

| 𖽆 | 𖽇 | 𖽈 | 𖽉 | 𖽊 |

| SYI | DZYI | TE | TSE | RTE |

Vowels and finals

| 𖽔 | 𖽕 | 𖽖 | 𖽗 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | AA | AHH | AN |

| 𖽘 | 𖽙 | 𖽚 | 𖽛 |

| ANG | O | OO | WO |

| 𖽜 | 𖽝 | 𖽞 | 𖽟 |

| W | E | EN | ENG |

| 𖽠 | 𖽡 | 𖽢 | 𖽣 |

| OEY | I | IA | IAN |

| 𖽤 | 𖽥 | 𖽦 | 𖽧 |

| IANG | IO | IE | II |

| 𖽨 | 𖽩 | 𖽪 | 𖽫 |

| IU | ING | U | UA |

| 𖽬 | 𖽭 | 𖽮 | 𖽯 |

| UAN | UANG | UU | UEI |

| 𖽰 | 𖽱 | 𖽲 | 𖽳 |

| UNG | Y | YI | AE |

| 𖽴 | 𖽵 | 𖽶 | 𖽷 |

| AEE | ERR | ROUNDED ERR | ER |

| 𖽸 | 𖽹 | 𖽺 | 𖽻 |

| ROUNDED ER | AI | EI | AU |

| 𖽼 | 𖽽 | 𖽾 | 𖽿 |

| OU | N | NG | UOG |

| 𖾀 | 𖾁 | 𖾂 | 𖾃 |

| YUI | OG | OER | VW |

| 𖾄 | 𖾅 | 𖾆 | 𖾇 |

| IG | EA | IONG | UI |

Positioning tone marks

| 𖾏 | 𖾐 | 𖾑 | 𖾒 |

|---|---|---|---|

| RIGHT | TOP RIGHT | ABOVE | BELOW |

Baseline tone marks

| 𖾓 | 𖾔 | 𖾕 | 𖾖 | 𖾗 | 𖾘 | 𖾙 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TONE-2 | TONE-3 | TONE-4 | TONE-5 | TONE-6 | TONE-7 | TONE-8 |

Archaic baseline tone marks

| 𖾚 | 𖾛 | 𖾜 | 𖾝 | 𖾞 | 𖾟 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REFORMED TONE-1 | REFORMED TONE-2 | REFORMED TONE-4 | REFORMED TONE-5 | REFORMED TONE-6 | REFORMED TONE-8 |

Unicode

The Pollard script was first proposed for inclusion in Unicode by John Jenkins in 1997.[5] It took many years to reach a final proposal in 2010.[6]

It was added to the Unicode Standard in January, 2012 with the release of version 6.1.

The Unicode block for Pollard script, called Miao, is U+16F00–U+16F9F:

| Miao[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+16F0x | 𖼀 | 𖼁 | 𖼂 | 𖼃 | 𖼄 | 𖼅 | 𖼆 | 𖼇 | 𖼈 | 𖼉 | 𖼊 | 𖼋 | 𖼌 | 𖼍 | 𖼎 | 𖼏 |

| U+16F1x | 𖼐 | 𖼑 | 𖼒 | 𖼓 | 𖼔 | 𖼕 | 𖼖 | 𖼗 | 𖼘 | 𖼙 | 𖼚 | 𖼛 | 𖼜 | 𖼝 | 𖼞 | 𖼟 |

| U+16F2x | 𖼠 | 𖼡 | 𖼢 | 𖼣 | 𖼤 | 𖼥 | 𖼦 | 𖼧 | 𖼨 | 𖼩 | 𖼪 | 𖼫 | 𖼬 | 𖼭 | 𖼮 | 𖼯 |

| U+16F3x | 𖼰 | 𖼱 | 𖼲 | 𖼳 | 𖼴 | 𖼵 | 𖼶 | 𖼷 | 𖼸 | 𖼹 | 𖼺 | 𖼻 | 𖼼 | 𖼽 | 𖼾 | 𖼿 |

| U+16F4x | 𖽀 | 𖽁 | 𖽂 | 𖽃 | 𖽄 | 𖽅 | 𖽆 | 𖽇 | 𖽈 | 𖽉 | 𖽊 | 𖽏 | ||||

| U+16F5x | 𖽐 | 𖽑 | 𖽒 | 𖽓 | 𖽔 | 𖽕 | 𖽖 | 𖽗 | 𖽘 | 𖽙 | 𖽚 | 𖽛 | 𖽜 | 𖽝 | 𖽞 | 𖽟 |

| U+16F6x | 𖽠 | 𖽡 | 𖽢 | 𖽣 | 𖽤 | 𖽥 | 𖽦 | 𖽧 | 𖽨 | 𖽩 | 𖽪 | 𖽫 | 𖽬 | 𖽭 | 𖽮 | 𖽯 |

| U+16F7x | 𖽰 | 𖽱 | 𖽲 | 𖽳 | 𖽴 | 𖽵 | 𖽶 | 𖽷 | 𖽸 | 𖽹 | 𖽺 | 𖽻 | 𖽼 | 𖽽 | 𖽾 | 𖽿 |

| U+16F8x | 𖾀 | 𖾁 | 𖾂 | 𖾃 | 𖾄 | 𖾅 | 𖾆 | 𖾇 | 𖾏 | |||||||

| U+16F9x | 𖾐 | 𖾑 | 𖾒 | 𖾓 | 𖾔 | 𖾕 | 𖾖 | 𖾗 | 𖾘 | 𖾙 | 𖾚 | 𖾛 | 𖾜 | 𖾝 | 𖾞 | 𖾟 |

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Published sources

- Enwall, Joakim (1994). A Myth Become Reality: History and Development of the Miao Written Language, two volumes. ISBN 9789171534231.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Pollard, Samuel (December 1909). "Gathering up the Fragments". The United Methodist Magazine. 2: 531–35.

- Wen, You (1938). "Lun Pollard Script". Xinan Bianjiang. 1: 43–53.

- Wen, You (1951), Guizhou Leishan xin chu canshi chukao. Huaxi wenwu Reprinted in Wen You (1985). Wen You lunji. Beijing: Zhongyang minzu xueyuan keyanchu.

References

- Pollard, Samuel (1919), Story of the Miao, London: Henry Hooks, p. 174

- Enwall 1994

- Tapp, N. (2011). "The Impact of Missionary Christianity Upon Marginalized Ethnic Minorities: The Case of the Hmong". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 20: 70–95. doi:10.1017/S0022463400019858. hdl:1885/22258.. Republished in Storch, Tanya, ed. (2006). Religions and Missionaries around the Pacific, 1500–1900. The Pacific World: Lands, Peoples and History of the Pacific, 1500–1900. Vol. 17. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 289–314. ISBN 9780754606673. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Duffy, John M. (2007). Writing from these roots: literacy in a Hmong-American community. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3095-3.

- Jenkins, John H. (21 May 1997). "L2/97-104: Proposal to add Pollard to Unicode/ISO-IEC 10646" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "N3789: Final proposal for encoding the Miao script in the SMP of the UCS" (PDF). 26 March 2010. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

External links

- "Description of the Pollard script". Omniglot. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- Edwin Dingle. "Across China on Foot". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved July 29, 2005. Dingle describes how Sam Pollard used positioning of vowel marks relative to consonants to indicate tones.

- "Miao Unicode, Open source font for users of the Miao script".

- Preliminary proposal for additions for Hei Yi to Miao block