Port of Piraeus

The Port of Piraeus (Greek: Λιμάνι του Πειραιά) is the chief sea port located in Piraeus, and on the Saronic Gulf on the western coasts of the Aegean Sea, the largest port in Greece and one of the largest in Europe.[6]

Port of Piraeus

| |

|---|---|

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | |

| Country | Greece |

| Location | Piraeus |

| Coordinates | 37°56′31″N 23°38′10″E |

| UN/LOCODE | GRPIR[1] |

| Details | |

| Operated by | Piraeus Port Authority (Athex: PPA) |

| Owned by | COSCO (67%) HRADF (7.14%)[2] Non-institutional investors (25.86%) |

| Type of harbour | Natural/artificial |

| Size | 3,900 hectares (39 km2) |

| Employees | 991[3] (2020) |

| Chairman & CEO | Fu Chengqiu |

| Statistics | |

| Annual container volume | |

| Passenger traffic | |

| Annual revenue | (PPA figures) |

| Net income | (PPA figures)[5] |

| Website Official website | |

The Chinese state-owned COSCO Shipping operate the port.

History

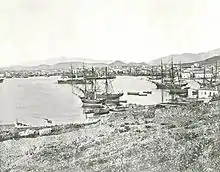

The Port of Piraeus served as the port of Athens since ancient times.[7][8]

Early Antiquity

Until the 3rd millennium BC, Piraeus was a rocky island connected to the mainland by a low-lying stretch of land that was flooded with sea water most of the year. It was then that the area was increasingly silted and flooding ceased, thus permanently connecting Piraeus to Attica and forming its ports, the main port of Cantharus and the two smaller of Zea and Munichia. In 493 BC, Themistocles initiated the fortifications of Piraeus and later advised the Athenians to take advantage of its natural harbours' strategic potential. In 483 BC, the Athenian fleet left the older harbour of Phaleron and it was transferred to Piraeus, distinguishing itself at the battle of Salamis between the Greek city-states and the Persians in 480 BC. In the following years Themistocles initiated the construction of the port and created the ship sheds (neosoikoi), while the Themistoclean Walls were completed in 471 BC, turning Piraeus into a great military and commercial harbour, which served as the permanent navy base for the mighty Athenian fleet.

Late Antiquity and Middle Ages

In the late 4th century BC Piraeus went into a long period of decline; the harbours were only occasionally used for the Byzantine fleet and the town was mostly deserted throughout the Ottoman occupation of Greece.

Present

In 2002 the Piraeus Port Authority (PPA) and the Greek government signed a concession agreement. The Greek government leased the port zone lands, buildings and facilities of Piraeus Port to PPA for 40 years. In 2008 the duration of the concession agreement was modified from 40 to 50 years. With this modification the lease is ending in 2052.[9]: 42 Since the Greek government-debt crisis started in late 2009 the Greek government planned to privatize several state-owned assets. These assets are believed to be worth around 50 billion euros. One of these assets is the Piraeus Port Authority (PPA).[10] The port is a major employer in the region.[11]

Ownership

The Piraeus Port Authority (PPA) is majority owned by China COSCO Shipping[12] (the successor of China Ocean Shipping (Group) Company (COSCO)), the 3rd largest container ship company in the world. In 2003 the port had its IPO, after which the port was majority owned by the Greek state (74.5%), while the rest was held by investors.[13]

In 2009, Greece leased the land of dock 2 and what would become dock 3 (both container berths) to COSCO's subsidiary COSCO Pacific for 35 years.[14] COSCO paid 100 million Euros each year as part of this arrangement.

"The port's geographic advantages and the quality services offered by us, have helped deliver rapid progress, in a crisis era" said Fu Chengqiu, managing director of Piraeus Container Terminal in 2012. With COSCO's investment, the port had broken their 2006 record of 1.5 million TEUs handled by 2011, with dock 2 (COSCO) handling 1.18 million TEUs and Dock 1 (Greek) handling 500,000 TEUs. In 2009 the financial crisis had brought the TEU volume down to 450,000 for the whole port.

In 2014 The Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF), the Greek government's privatization agency, sought to sell a majority stake of the port to finance debt. In 2016, COSCO bought 51% of the port from the HRADF for 280.5 million Euros.[15] As per an escrow, COSCO will pay 88 million more Euros for an additional 16% stake by 2021, contingent on COSCO making certain investments in the port, including passenger and cruise expansions, dredging, and expansion of the car terminal.[16]

As of 2020, the Port of Piraeus is majority owned by COSCO with 67% of shares (16% in escrow shares).[16] The HRADF has 7.14% of shares.[13] The rest (25.86%) is held by non-institutional investors.[13] In October 2021, the HRADF transferred the 16% escrow shares to COSCO. COSCO paid 88 million euros for it, and 11.87 million euros in accrued interest as well as a letter of guarantee of 29 million euros.[17]

Under COSCO ownership

In October 2009 Greece leased docks 2 and 3 from PPA to the China Ocean Shipping (Group) Company (in short: COSCO) for a 35-year-period. For its presence at the port COSCO is paying 100 million euros every year.[10] Terminal 1 is operated by PPA S.A. and has a capacity of nearly 1 million TEUs. Terminal 2's capacity is 3 million TEUs and is run by Piraeus Container Terminal PCT S.A., a subsidiary of COSCO. In 2013, PCT finished the construction of Terminal 3 with a capacity of roughly 2.7 million TEU. The total port capacity is 6.7 m TEUs. COSCO's involvement was accompanied by protest. According to trade unionists of PPA, the arrival of COSCO led to reductions in salary and social benefits, exclusion of union members and increased pressures on time and performance at the expense of worker safety.[18] According to an interview in 2012 with Harilaos N. Psaraftis, a professor of maritime transport in Athens, in some cases the salaries of workers were $181,000 a year with overtime before the 20% general pay-cuts imposed on public employees. Due to union safety rules a team of nine people was required to work a gantry crane. COSCO pays around $23,300 and only requires four people at a crane.[18]

Economic performance of container handling has greatly improved since 2009. Before COSCO took over, the port's container handling record was at 1.5 million TEUs. These figures rose to 3.692 million containers in 2017.[19] As a result, revenue and profits soared. In 2017 the Athens stock exchange listed company (OLP) almost doubled its pre-tax profits from 11 to 21.2 million euros.[20]

The port is also used by Chinese naval vessels assigned to escort merchant vessels against pirate activities along the Somali coast and in the Gulf of Aden since 2008.[21]

Labour relations

In 2012, the Greek government passed a law reducing the pay of all government jobs by 35 to 40 percent.[22] At the time, Piraeus Port Authority (PPA) (the company legally allowed to operate the port) was considered a public company because it was majority held by the Greek State. Consequently, the port was subject to the wage reduction.

In 2014 the Greek government sought to sell equity of the port as part of an agreement with the EU to recover from debt. This was met with criticism and resistance by the port's local union as well as a significant part of the Greek population.[22] The Dockworker's union went on strike several times.[23][24][25] The push to sell the port stalled while the controlling federal political party changed, but that was short lived.[22] Negotiations between the Greek government and COSCO soon resumed while the resistance to foreign control of the port started to decline. The port is sometimes known as the gateway to Europe due to its location relative to Europe, Asia, and northern Africa. As such, the union wanted to keep the port under Greek control.[22] However, at that point the privatization efforts of the government were inevitable as Greece struggled to raise money to finance debt.

The Greek government went ahead with the decision to sell 51 percent of the PPA to COSCO in 2016, and hand over another 16 percent by 2021. Chinese state news agencies report that the negotiation was easy for COSCO because it had already invested more than 300 million Euros into upgrading the container terminals since 2009, and promised to keep investing. COSCO's container terminals had set records for the port at this time. A dockworker, Constantinos Tsourakis, said at the time "This is not a concession, it’s a giveaway of property belonging to the Greek people. Why should China be masters of the game at Piraeus and not the Greek state?"

COSCO and the union reached an agreement early on that established work environment concerns, including safety, working hours, and a gantry crane staffing dispute.[22] The 35/40 percent government mandated pay reduction ceased to apply as soon as COSCO owned 51 percent, because PPA was no longer a public company. One of the union's expectations of the investment was that COSCO would up the wages to match what they were before the reduction. However, the wages have been stagnant (as of 2017) since the 2012 reductions.[22] This hasn't sat well with the union, which is currently in negotiations regarding pay. COSCO maintains that they did not reduce the pay of any workers. The union Gen. Secretary, Giorgios Gogos, agrees with that assessment, but says the expectation of COSCO to remove the 35/40 percent reduction remains a problem. He also points out that the 51 percent stake (which will increase to 67 percent in 2021) means that the 100 million dollars that the COSCO subsidiary pays each year to the PPA for use of dock 2 and 3 ends up back in COSCO's hands, not those of the Greek government or people, as originally intended.[22]

The Dockworker's Union represents 350 workers in Piraeus and is a member of the General Confederation of Greek Workers (Greek) and a founding member of the International Dockworkers Council (International).[26]

Statistics

With about 18.6 million passengers Piraeus was the busiest passenger port in Europe in 2014.[27] Since its privatization in 2009 the port's container handling has grown rapidly. Piraeus handled 5.65 million TEUs in 2019[28] According to Lloyd's list for top 100 container ports in 2015 Piraeus ranked 8th in Europe and 3rd the Mediterranean sea.[29] The port of Piraeus was expected to become the busiest port of the Mediterranean in terms of container traffic by 2019.[30] Piraeus handled 4.9 million TEUs in 2018, an increase of 19,4% compared with 2017 climbing to the number two position of all Mediterranean ports. [31] As of April 2016 the port ranks 39th globally in terms of container capacity.[32] In 2007 the Port of Piraeus handled 20,121,916 tonnes of cargo and 1,373,138 TEUs, making it the busiest cargo port in Greece and the largest container port in the country and the East Mediterranean Sea Basin.[33][34]

| Year | 2007 |

|---|---|

| RoRo* | 1,108,928 |

| Bulk cargo* | 606,454 |

| General cargo* | 6,278,635 |

| Containers* | 12,127,899 |

| Total* | 20,121,916 |

- * figures in tonnes

Terminals

Container terminal

The container part of the port is made up of three terminals:

- Terminal 1 with a total capacity of 1,1 million TEUs

- Terminal 2 with a total capacity of 3 million TEUs

- Terminal 3, completed in 2016 with a total capacity of roughly 2,7 million TEUs

As of 2021 the total capacity is hence now standing at 8,3m TEUs.[35][36]

Cargo terminal

The cargo terminal has a storage area of 180,000 m2 and an annual traffic capacity of 25,000,000 tonnes.

Automobile terminal

The Port of Piraeus has two car terminals of approximately 190,000 m2, storage capacity of 12,000 cars and a transshipment capacity of 670,000 units per year.[37]

In 2017 the automobile terminal handled 430,000 automobiles, 100,000 for the local market and 330,000 transhipments.[38]

Passenger terminal

The Port of Piraeus is the largest passenger port in Europe and one of the largest passenger ports in the world. It has a total quay length of 2.8 km and draft of up to 11 m. Vehicle traffic reaches 2.5m while in 2017, passenger traffic reached 15.5m.[38]

Total cruise traffic in 2019 was 1,098,091 passengers, compared with 961,632 in 2018, a 14.2% increase. Ferry Shipping News attributes this significant increase to "PPA SA’s outward focus and dedication to cruise attraction policy coupled with increased demand for cruises in the eastern Mediterranean".[39]

About a third of cruise sailings in Piraeus are home ported in Piraeus. In 2018, there were 524 ship arrivals, while there were 622 in 2019.[39]

Piraeus Cruise Port has 11 vessel berths, with a total quay length of 2,800 meters. It can dock vessels with a draft of 11 meters. Each berth has environmental/waste services available. PPA operates three cruise terminals, "A", "B", and "C" . Its security is International Ship and Port Facility Security Code (ISPS) compliant.[40]

Terminal A is the main terminal and is open 24 hours. It is within walking distance of the center of the Municipality of Piraeus. It can handle 1,200 passengers an hour. Two medium-sized ships can check in simultaneously. Terminal B was built in 2013 which can handle mega cruise ships, with a draft up to 11 meters. It has the same amenities as Terminal A; however, there is space for 120 tour buses, and it can handle 1500 passengers an hour. Terminal C is the smallest. It was built in 2003, but expanded in 2016. It can handle 700 passengers an hour, and features customs and a check in/departure hall. Free shuttle bus service is offered to bring passengers to the other terminals (to exit/enter the port).[40]

For the 2004 Athens Olympic Games, 13 cruise ships were docked in Piraeus to serve as floating hotels.[41]

Piraeus consistently ranks in the top 10 cruise destinations in Europe and the Mediterranean. Piraeus has been the top cruise destination in Greece for the tenth consecutive year, beating Santorini, Mykonos, Rhodes, and Crete.[42] In 2019 the port was awarded "Best Cruise Port in the Eastern Mediterranean Region" by MedCruise.

| Years | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic passengers | 11,713,269 | 11,159,274 | 11,484,763 | 11,668,647 | 11,572,678 |

| Ferry passengers | 8,397,292 | 8,393,053 | 7,977,880 | 7,636,426 | 8,395,492 |

| Foreign passengers | 823,339 | 757,552 | 925,782 | 1,202,190 | 1,554,747 |

| Total traffic | 20,933,900 | 20,255,879 | 20,388,425 | 20,507,263 | 21,522,917 |

Ferry destinations

A plethora of destinations in Greece can be reached by ferry from the harbour, including islands in the Saronic islands, the Cyclades, Crete, the islands on the Northern Aegean Sea and the Dodecanese, among others. A full list can be seen here.

Transportation links

Piraeus metro station is located next to the port (37°56′53″N 23°38′35″E) and is an interchange station between Line 1 and Line 3. Is also the southern terminus of Athens Metro Line 1. North of the metro station is the Suburban Railway Station of the Athens Suburban Railway (Proastikos) to Acharnes Junction and other regional destinations as well as Intercity Connections via transfer to Athens Central Railway Station.[43]

Free shuttle buses inside the port run from across the Metro Line 1 Terminal Station, around the north side of the port to the ships sailing for Crete, the Eastern Aegean and the Dodecanese. A direct Airport Express bus route X96 runs 24/7 between the port and Athens International Airport. Other public buses connect Piraeus with various other areas such as southern coastal zone and central Athens.

Environment

Piraeus Port Authority's (PPA) 2013 environmental flyer calls itself the "Green Port of the Mediterranean Sea".[44] The port is a member of EcoPorts.[45] It is also ISO 14001 Certified by Lloyd's Register and Bureau Veritas.[45] PPA states on its website that it has disposal services for all types of ship-generated waste.[46] The port conducts water quality tests and works with nearby schools.[47]

The port has partnered with the University of Piraeus and Cardiff University to implement a sea water quality monitoring program. Bi-annually, the water and sediment throughout the whole port area is sampled and tested.[47] Some parameters measured include pH, Turbidity, Salinity, Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD), Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD), E-Coli, Total Coliforms, TDS, and Heavy Metals.[44]

For air quality monitoring, the port partnered with the National Technical University of Athens School of Chemical Engineers. An air quality monitoring station was installed to take measurements of BTEX, CO, NOx, SO2, O

3, and PM2.5 and PM10, 24 hours a day. PPA has also collaborated with the Agricultural University of Athens to enhance the greenery around the port for aesthetic purposes, as well as to remove pollutants from the air.[47] The purposes of the monitoring initiatives so far has just been for data collection.

In 2004 for the Athens Olympic Games, a permanent sewage network was built for the cruise ships that were docked in Piraeus as floating hotels.[46] The sewage travels to the Wastewater Treatment Plant of Athens.[46] This development allows all cruise ships to be able to discharge sewage at the port.

PPA is a member of EcoPorts. As part of EcoPorts, the port has been continuously Port Environmental Review System (PERS) certified since 2004.[48] PERS is a standard for port environmental management. One of the requirements of EcoPorts is an environmental management system.[49] The port has an oil and Hazardous and Noxious Substances (HNS) contingency plan.[50] In 2016, PPA was independently tested to make sure pollution levels were within legal limits, which they were.

The port is currently looking into LNG as a bunker fuel, as well as cold ironing for the cruise terminals.[51] It is also conducting a CO2 footprint assessment. A green roof was installed on the top of one of the new container terminal buildings.[47]

References

- "UNLOCODE (GR) - GREECE". service.unece.org. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- MarketScreener. "PIRAEUS PORT AUTHORITY : Shareholders Board Members Managers and Company Profile - GRS470003013 - MarketScreener". www.marketscreener.com.

- ANNUAL_FINANCIAL_REPORT_2020.pdf Piraeus Port Authority S.A. p24

- "Port of Piraeus holds". Metaforespress. 2021-01-19. Retrieved 2021-01-19.

- "The financial results for the year 2019 of PPA S.A. were presented to the Hellenic Fund and Asset Management Association". Piraeus Port Authority. 2020-05-19. Retrieved 2020-05-21.

- "Greece to offer concessions but won't privatise 10 ports". Seatrade Maritime News. 2019.

- Στρατηγική - Όραμα (in Greek). Piraeus Port Authority S.A. Archived from the original on 2010-11-27. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- Hellander, Paul (2008). Greece. Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-1-74104-656-4.

- "PPA: Annual Financial Report 2016". 2017-02-16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-18. Retrieved 2017-02-17.

- Fu Jing (2012-06-19). "COSCO eyeing further Piraeus port investment". chinadaily.com.cn. Retrieved 2012-11-21.

- Fu Jing (2018-06-19). "China bought most of Greece's main port and now it wants to make it the biggest in Europe". CNBC. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- "Greek President Hopes For More Investments Following Piraeus Port Authority Deal | Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide". 2016-04-26. Archived from the original on 2016-04-26. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Shareholders". www.olp.gr. Archived from the original on 2017-02-24. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- 1Wright, Robert; Hope, Kerin; Kwong, Robin (5 June 2008). "Cosco set to control Greek port". Financial Times. Retrieved 14 December 2020.

- "China's Cosco acquires 51 pct stake in Greece's Piraeus Port". Reuters. 2016-08-10. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Presentation of P.P.A SA". www.olp.gr. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Greece completes transfer of 16% stake in Piraeus port to COSCO". Reuters. 2021-10-07. Retrieved 2021-10-08.

- Liz Alderman (2012-10-10). "Under Chinese, a Greek Port Thrives". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-11-21.

- "Αύξηση 6,4% στη διακίνηση κοντέινερ από ΟΛΠ το 2017, του Νίκου Χ. Ρουσάνογλου - Kathimerini". www.kathimerini.gr.

- "Piraeus Port Authority posts record profits - Kathimerini". www.ekathimerini.com.

- Liz Alderman (2015-10-10). "Chinese military ships arrive in Piraeus port". GB Times. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- Gogos, Giorgos (2020-04-03). "Forced Privatization of The Greek Port of Piraeus, One Year Later" (Interview by Dimitri Lascaris). Youtube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-15.

- "Workers protest as Greece sells Piraeus Port to China COSCO". Reuters. 2016-04-08. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Greek Port Workers Strike Again Over Privatization". The Maritime Executive. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- Ship; bunker.com. "Greek Dock Workers Walk Out, Protest Over Piraeus and Thessaloniki Port Privatisation". Ship & Bunker. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Ιστορικά Στοιχεία, Ένωση Μονίμων & Δοκίμων Λιμενεργατών Ο.Λ.Π." www.dockers.gr. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "World Container Traffic Data 2015" (PDF). International Association of Ports and Harbors (IAPH). 2016-06-10. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-06-15. Retrieved 2016-04-09.

- "Greece's Piraeus becomes top container-handling port in Mediterranean - Xinhua | English.news.cn". Archived from the original on May 24, 2022.

- "Lloyd's List". Lloyd's List.

- "Die Zeit: O Πειραιάς μεγαλύτερο λιμάνι της Μεσογείου ως το 2019 - Kathimerini". www.kathimerini.gr.

- Glass, David. "Piraeus becomes second largest port in the Med". www.seatrade-maritime.com.

- "Greek president hopes for more investments following Piraeus Port Authority deal". Hellenic Shipping News. 11 April 2016. Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- OLP (2011-10-05). "PPA Statistics 2007-2010". Archived from the original on 2012-11-23. Retrieved 2012-11-22.

- "(Container Terminal)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-27. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- "olp.gr - Container Terminal". www.olp.gr. Retrieved 2021-11-09.

- Ose, Mixanikos. "MixanikosOse: Ας γνωρίσουμε το Ικόνιο (δηλαδή το εμπορικό Λιμάνι του Πειραιά - έδρα της COSCO στην χώρα μας)". mixanikosose.blogspot.com.

- "Car Terminal". Olp.gr. Archived from the original on 2009-06-03. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- "Παρουσιάσεις Ο.Λ.Π. ΑΕ". www.olp.gr. Archived from the original on 2018-08-16. Retrieved 2018-08-16.

- "Port of Piraeus in Focus". Ferry Shipping News. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Cruise Terminal Presentation 2017" (PDF). Piraeus Port Authority. 2 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Solomonidis, Christos. "Port of Piraeus - Olympic Games 2004". Rogan Associates.

- ANA. "Cruise Ship Arrivals in Greece up Almost 15% in 2019". The National Herald. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- 2012 Network Statement, Athens: OSE, 2012, p. 3.3, archived from the original (pdf) on 2013-03-10

- "Piraeus Port, The Green Port of the Mediterranean Sea" (PDF). Piraeus Port Authority.

- ""EcoPorts Port" Status - Environmental Management Standard PERS". www.olp.gr. Archived from the original on 2020-02-25. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Ship-generated Waste Management Plan". www.olp.gr. Archived from the original on 2020-01-28. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Environmental Quality Monitoring Programs". www.olp.gr. Archived from the original on 2020-02-25. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- Ullyett, Richard (2019-02-24). "Piraeus Port Authority details environmental plan". PortSEurope. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "The port of Piraeus pioneer in the principles of environmental sustainability | Hellenic Shipping News Worldwide". www.hellenicshippingnews.com. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- "Environmental Report" (PDF). Piraeus Port Authority. Retrieved 2020-04-14.

- "Home". elemedproject. Retrieved 2021-11-09.