History of Albania

During classical antiquity, Albania was home to several Illyrian tribes such as the Ardiaei, Albanoi, Amantini, Enchele, Taulantii and many others, but also Thracian and Greek tribes, as well as several Greek colonies established on the Illyrian coast. In the 3rd century BC, the area was annexed by Rome and became part of the Roman provinces of Dalmatia, Macedonia and Moesia Superior. Afterwards, the territory remained under Roman and Byzantine control until the Slavic migrations of the 7th century. It was integrated into the Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century.

| History of Albania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

In the Middle Ages, the Principality of Arbër and a Sicilian union known as the medieval Kingdom of Albania were established. Some areas became part of the Venetian and later Serbian Empire. Between the mid-14th and the late 15th centuries, most of modern-day Albania was dominated by Albanian principalities, when the Albanian principalities fell to the rapid invasion of the Ottoman Empire. Albania remained under Ottoman control as part of the province of Rumelia until 1912; with some interruptions during the 18th and 19th century with the establishment of autonomy minded Albanian lords. The first independent Albanian state was founded by the Albanian Declaration of Independence following a short occupation by the Kingdom of Serbia. The formation of an Albanian national consciousness dates to the later 19th century and is part of the larger phenomenon of the rise of nationalism under the Ottoman Empire.

A short-lived monarchical state known as the Principality of Albania (1914–1925) was succeeded by an even shorter-lived first Albanian Republic (1925–1928). Another monarchy, the Kingdom of Albania (1928–1939), replaced the republic. The country endured occupation by Italy just prior to World War II (1939–1945). After the Armistice of Cassibile between Italy and the Allies, Albania was occupied by Nazi Germany. Following the collapse of the Axis powers, Albania became a one-party communist state, the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, which for most of its duration was dominated by dictator Enver Hoxha (died 1985). Hoxha's political heir Ramiz Alia oversaw the disintegration of the "Hoxhaist" state during the wider collapse of the Eastern Bloc in the later 1980s.

The communist regime collapsed in 1990, and the former communist Party of Labour of Albania was routed in elections in March 1992, amid economic collapse and social unrest. The unstable economic situation led to an Albanian diaspora, mostly to Italy, Greece, Switzerland, Germany and North America during the 1990s. The crisis peaked in the Albanian Turmoil of 1997. An amelioration of the economic and political conditions in the early years of the 21st century enabled Albania to become a full member of NATO in 2009. The country is applying to join the European Union.

Prehistory

Mesolithic & Neolithic

The first traces of human presence in Albania, dating to the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic eras, were found in the village of Xarrë, near Sarandë and Dajti near Tirana.[1] The objects found in a cave near Xarrë include flint and jasper objects and fossilized animal bones, while those found at Mount Dajt comprise bone and stone tools similar to those of the Aurignacian culture. The Paleolithic finds of Albania show great similarities with objects of the same era found at Crvena Stijena in Montenegro and north-western Greece.[1] There are several archaeological sites in Albania that carry artifacts dating from the Neolithic era, and they are dated between 6,000 and the end of the EBA. The most important are found in Maliq, Gruemirë, Dushman (Dukagjin), on the Erzen river (close to Shijak), near Durrës, Ziçisht, Nepravishtë, Finiq, and Butrint.[2]

Bronze Age

The next period in the prehistory of Albania coincides with the Indo-Europeanization of the Balkans, which involved Pontic steppe migrations which brought the Indo-European languages in the region and the formation of the Paleo-Balkan peoples as the result of fusion between the Indo-European-speaking population and the Neolithic population. In Albania, consecutive movements from the northern parts of the region which became known as Illyria in the Iron Age had a significant impact in the formation of the new post-Indo-European migration population. The ancestral groups to Iron Age Illyrians are usually identified in Albania towards the end of the EBA with movements from north of Albania and are linked to the construction of tumuli burial grounds of patrilineally organized clans.[3] Some of the first tumuli date to 26th century BCE. These burial mounds belong to the southern expression of the Adriatic-Ljubljana culture (related to Cetina culture) which moved southwards along the Adriatic from the northern Balkans. The same community built similar mounds in Montenegro (Rakića Kuće) and northern Albania (Shtoj).[4]

In the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age a number of possible population movements occurred in the territories of modern Albania, for example the settlement of the Bryges in areas of southern Albania-northwestern Greece[5] and Illyrian tribes into central Albania.[6] The latter derived from early an Indo-European presence in the western Balkan Peninsula. The movement of the Byrgian tribes can be assumed to coincide with the beginning Iron Age in the Balkans during the early 1st millennium BC.[7]

Antiquity

Illyrians

The Illyrians were a group of tribes who inhabited the western Balkans during the classical times. The territory the tribes covered came to be known as Illyria to Greek and Roman authors, corresponding roughly to the area between the Adriatic Sea in the west, the Drava river in the north, the Morava river in the east and the mouth of Vjosë river in the south.[8][9] The first account of the Illyrian peoples comes from the Coastal Passage contained in a periplus, an ancient Greek text of the middle of the 4th century BC.[10]

Several Illyrian tribes that resided in the region of Albania were the Ardiaei, Taulantii and Albanoi[11] in central Albania,[12] the Parthini, the Abri and the Caviii in the north, the Enchelei in the east,[13] the Bylliones in the south and several others. In the westernmost parts of the territory of Albania, along with the Illyrian tribes, lived the Bryges,[14] a Phrygian people, and in the south[15][16] lived the Greek tribe of the Chaonians.[14][17][18]

In the 4th century BC, the Illyrian king Bardylis united several Illyrian tribes and engaged in conflicts with Macedon to the south-east, but was defeated. Bardyllis was succeeded by Grabos II,[19] then by Bardylis II,[20] and then by Cleitus the Illyrian,[20] who was defeated by Alexander the Great.

Around 230 BC, the Ardiaei briefly attained military might under the reign of king Agron. Agron extended his rule over other neighbouring tribes as well.[21] He raided parts of Epirus, Epidamnus, and the islands of Corcyra and Pharos. His state stretched from Narona in Dalmatia south to the river Aoos and Corcyra. During his reign, the Ardiaean Kingdom reached the height of its power. The army and fleet made it a major regional power in the Balkans and the southern Adriatic. The king regained control of the Adriatic with his warships (lembi), a domination once enjoyed by the Liburnians. None of his neighbours were nearly as powerful. Agron divorced his (first) wife.

Agron suddenly died, c. 231 BC, after his triumph over the Aetolians. Agron's (second) wife was Queen Teuta, who acted as regent after Agron's death. According to Polybius, she ruled "by women's reasoning".[22] Teuta started to address the neighbouring states malevolently, supporting the piratical raids of her subjects. After capturing Dyrrhachium and Phoenice, Teuta's forces extended their operations further southward into the Ionian Sea, defeating the combined Achaean and Aetolian fleet in the Battle of Paxos and capturing the island of Corcyra. Later on, in 229 BC, she clashed with the Romans and initiated the Illyrian Wars. These wars, which were spread out over 60 years, eventually resulted in defeat for the Illyrians by 168 BC and the end of Illyrian independence when King Gentius was defeated by a Roman army after heavy clashes with Rome and Roman allied cities such as Apollonia and Dyrrhachium under Anicius Gallus. After his defeat, the Romans split the region into three administrative divisions,[23] called meris.[24]

Greeks and Romans

Beginning in the 7th century BC, Greek colonies were established on the Illyrian coast. The most important were Apollonia, Aulon (modern-day Vlorë), Epidamnos (modern-day Durrës), and Lissus (modern-day Lezhë). The city of Buthrotum (modern-day Butrint), a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is probably more significant today than it was when Julius Caesar used it as a provisions depot for his troops during his campaigns in the 1st century BC. At that time, it was considered an unimportant outpost, overshadowed by Apollonia and Epidamnos.[25]

The lands comprising modern-day Albania were incorporated into the Roman Empire as part of the province of Illyricum above the river Drin, and Roman Macedonia (specifically as Epirus Nova) below it. The western part of the Via Egnatia ran inside modern Albania, ending at Dyrrachium. Illyricum was later divided into the provinces of Dalmatia and Pannonia.

The Roman province of Illyricum or[26][27] Illyris Romana or Illyris Barbara or Illyria Barbara replaced most of the region of Illyria. It stretched from the Drilon River in modern Albania to Istria (Croatia) in the west and to the Sava River (Bosnia and Herzegovina) in the north. Salona (near modern Split in Croatia) functioned as its capital. The regions which it included changed through the centuries though a great part of ancient Illyria remained part of Illyricum.

South Illyria became Epirus Nova, part of the Roman province of Macedonia. In 357 AD the region was part of the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum one of four large praetorian prefectures into which the Late Roman Empire was divided. By 395 AD dioceses in which the region was divided were the Diocese of Dacia (as Pravealitana), and the Diocese of Macedonia (as Epirus Nova). Most of the region of modern Albania corresponds to the Epirus Nova.

Christianization

Christianity came to Epirus nova, then part of the Roman province of Macedonia.[28] Since the 3rd and 4th century AD, Christianity had become the established religion in Byzantium, supplanting pagan polytheism and eclipsing for the most part the humanistic world outlook and institutions inherited from the Greek and Roman civilizations. The Durrës Amphitheatre (Albanian: Amfiteatri i Durrësit) is a historic monument from the time period located in Durrës, Albania, that was used to preach Christianity to civilians during that time.

When the Roman Empire was divided into eastern and western halves in AD 395, Illyria east of the Drinus River (Drina between Bosnia and Serbia), including the lands form Albania, were administered by the Eastern Empire but were ecclesiastically dependent on Rome. Though the country was in the fold of Byzantium, Christians in the region remained under the jurisdiction of the Pope until 732. In that year the iconoclast Byzantine emperor Leo III, angered by archbishops of the region because they had supported Rome in the Iconoclastic Controversy, detached the church of the province from the Roman pope and placed it under the patriarch of Constantinople.

When the Christian church split in 1054 between Eastern Orthodoxy and Catholicism, the region of southern Albania retained its ties to Constantinople, while the north reverted to the jurisdiction of Rome. This split marked the first significant religious fragmentation of the country. After the formation of the Slav principality of Dioclia (modern Montenegro), the metropolitan see of Bar was created in 1089, and dioceses in northern Albania (Shkodër, Ulcinj) became its suffragans. Starting in 1019, Albanian dioceses of the Byzantine rite were suffragans of the independent Archdiocese of Ohrid until Dyrrachion and Nicopolis, were re-established as metropolitan sees. Thereafter, only the dioceses in inner Albania (Elbasan, Krujë) remained attached to Ohrid. In the 13th century during the Venetian occupation, the Latin Archdiocese of Durrës was founded.

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

After the region fell to the Romans in 168 BC it became part of Epirus nova that was, in turn, part of the Roman province of Macedonia. When the Roman Empire was divided into East and West in 395, the territories of modern Albania became part of the Byzantine Empire. Beginning in the first decades of Byzantine rule (until 461), the region suffered devastating raids by Visigoths, Huns, and Ostrogoths. In the 6th and 7th centuries, the Slavic invasion of Europe forced Albanians and Vlachs to pull back into the mountainous regions and adopt nomadic lifestyle, or flee into Byzantine Greece.[29]

In general, the invaders destroyed or weakened Roman and Byzantine cultural centres in the lands that would become Albania.[30]

In the late 11th and 12th centuries, the region played a crucial part in the Byzantine–Norman wars; Dyrrhachium was the westernmost terminus of the Via Egnatia, the main overland route to Constantinople, and was one of the main targets of the Normans (cf. Battle of Dyrrhachium (1081)). Towards the end of the 12th century, as Byzantine central authority weakened and rebellions and regionalist secessionism became more common, the region of Arbanon became an autonomous principality ruled by its own hereditary princes. In 1258, the Sicilians took possession of the island of Corfu and the Albanian coast, from Dyrrhachium to Valona and Buthrotum and as far inland as Berat. This foothold, reformed in 1272 as the "Kingdom of Albania", was intended by the dynamic Sicilian ruler, Charles of Anjou, to become the launchpad for an overland invasion of the Byzantine Empire. The Byzantines, however, managed to recover most of Albania by 1274, leaving only Valona and Dyrrhachium in Charles' hands. Finally, when Charles launched his much-delayed advance, it was stopped at the Siege of Berat in 1280–1281. Albania would remain largely part of the Byzantine empire until the Byzantine civil war of 1341–1347 when it fell shortly to the hands of the Serbian ruler Stephen Dushan. During this time, the territory became Albanian majority as the Black Death wiped out much of its Greek population.[29]

In the mid-9th century, most of eastern Albania became part of the Bulgarian Empire. The area, known as Kutmichevitsa, became an important Bulgarian cultural center in the 10th century with many thriving towns such as Devol, Glavinitsa (Ballsh) and Belgrad (Berat). When the Byzantines managed to conquer the First Bulgarian Empire the fortresses in eastern Albania were some of the last Bulgarian strongholds to submit to the Byzantines. Later the region was recovered by the Second Bulgarian Empire.

In the Middle Ages, the name Arberia began to be increasingly applied to the region now comprising the nation of Albania. The first undisputed mention of Albanians in the historical record is attested in a Byzantine source for the first time in 1079–1080, in a work titled History by Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates, who referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrhachium. A later reference to Albanians from the same Attaliates, regarding the participation of Albanians in a rebellion around 1078, is undisputed.[31]

Principality of Arbër

.png.webp)

In 1190, the Principality of Arbër (Arbanon) was founded by archon Progon in the region of Krujë. Progon was succeeded by Gjin Progoni and then Dhimitër Progoni. Arbanon extended over the modern districts of central Albania, with its capital located at Krujë.

The principality of Arbanon was established in 1190 by the native archon Progon in the region surrounding Kruja, to the east and northeast of Venetian territories.[32] Progon was succeeded by his sons Gjin and then Demetrius (Dhimitër), who managed to retain a considerable degree of autonomy from the Byzantine Empire.[33] In 1204, Arbanon attained full, though temporary, political independence, taking advantage of the weakening of Constantinople following its pillage during the Fourth Crusade.[34] However, Arbanon lost its large autonomy ca. 1216, when the ruler of Epirus, Michael I Komnenos Doukas, started an invasion northward into Albania and Macedonia, taking Kruja and ending the independence of the principality of Arbanon following the death of Dhimitër.[35] After the death of Demetrius, the last ruler of the Progon family, the same year, Arbanon was successively controlled subsequently by the Despotate of Epirus, the Bulgarian Empire and, from 1235, by the Empire of Nicaea.[36]

During the conflicts between Michael II Komnenos Doukas of Epirus and Emperor John III Doukas Vatatzes, Golem (ruler of Arbanon at the time) and Theodore Petraliphas, who were initially Michael's allies, defected to John III in 1252.[37] He is last mentioned in the sources among other local leaders, in a meeting with George Akropolites in Durrës in 1256. Arbanon was a beneficiary of the Via Egnatia trade road, which brought wealth and benefits from the more developed Byzantine civilization.[38]

High Middle Ages

After the fall of the Principality of Arber in territories captured by the Despotate of Epirus, the Kingdom of Albania was established by Charles of Anjou. He took the title of King of Albania in February 1272. The kingdom extended from the region of Durrës (then known as Dyrrhachium) south along the coast to Butrint. After the failure of the Eighth Crusade, Charles of Anjou returned his attention to Albania. He began contacting local Albanian leaders through local catholic clergy. Two local Catholic priests, namely John from Durrës and Nicola from Arbanon, acted as negotiators between Charles of Anjou and the local noblemen. During 1271 they made several trips between Albania and Italy eventually succeeding in their mission.[39]

On 21 February 1272, a delegation of Albanian noblemen and citizens from Durrës made their way to Charles' court. Charles signed a treaty with them and was proclaimed King of Albania "by common consent of the bishops, counts, barons, soldiers and citizens" promising to protect them and to honor the privileges they had from Byzantine Empire.[40] The treaty declared the union between the Kingdom of Albania (Latin: Regnum Albanie) with the Kingdom of Sicily under King Charles of Anjou (Carolus I, dei gratia rex Siciliae et Albaniae).[39] He appointed Gazzo Chinardo as his Vicar-General and hoped to take up his expedition against Constantinople again. Throughout 1272 and 1273 he sent huge provisions to the towns of Durrës and Vlorë. This alarmed the Byzantine Emperor, Michael VIII Palaiologos, who began sending letters to local Albanian nobles, trying to convince them to stop their support for Charles of Anjou and to switch sides. However, the Albanian nobles placed their trust on Charles, who praised them for their loyalty. Throughout its existence the Kingdom saw armed conflict with the Byzantine empire. The kingdom was reduced to a small area in Durrës. Even before the city of Durrës was captured, it was landlocked by Karl Thopia's principality. Declaring himself as Angevin descendant, with the capture of Durrës in 1368 Karl Thopia created the Princedom of Albania. During its existence Catholicism saw rapid spread among the population which affected the society as well as the architecture of the Kingdom. A Western type of feudalism was introduced and it replaced the Byzantine Pronoia.

Principalities and League of Lezhë

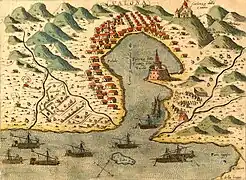

In 1371, the Serbian Empire was dissolved and several Albanian principalities were formed including the Principality of Kastrioti, Principality of Albania and Despotate of Arta as the major ones. In the late 14th and the early 15th century the Ottoman Empire conquered parts of south and central Albania. The Albanians regained control of their territories in 1444 when the League of Lezhë was established, under the rule of George Kastrioti Skanderbeg, the Albanian national hero. The League was a military alliance of feudal lords in Albania forged in Lezhë on 2 March 1444, initiated and organised under Venetian patronage[41] with Skanderbeg as leader of the regional Albanian and Serbian chieftains united against the Ottoman Empire.[42] The main members of the league were the Arianiti, Balšić, Dukagjini, Muzaka, Spani, Thopia and Crnojevići. For 25 years, from 1443 to 1468, Skanderbeg's 10,000-man army marched through Ottoman territory winning against consistently larger and better supplied Ottoman forces.[43] Threatened by Ottoman advances in their homeland, Hungary, and later Naples and Venice – their former enemies – provided the financial backbone and support for Skanderbeg's army.[44] By 1450 it had certainly ceased to function as originally intended, and only the core of the alliance under Skanderbeg and Araniti Comino continued to fight on.[45] After Skanderbeg's death in 1468, the sultan "easily subdued Albania," but Skanderbeg's death did not end the struggle for independence,[46] and fighting continued until the Ottoman siege of Shkodra in 1478–79, a siege ending when the Republic of Venice ceded Shkodra to the Ottomans in the peace treaty of 1479.

Ottoman Era

Early Ottoman period

Ottoman supremacy in the west Balkan region began in 1385 with their success in the Battle of Savra. Following that battle, the Ottoman Empire in 1415 established the Sanjak of Albania[47] covering the conquered parts of Albania, which included territory stretching from the Mat River in the north to Chameria in the south. In 1419, Gjirokastra became the administrative centre of the Sanjak of Albania.[48]

The northern Albanian nobility, although tributary of the Ottoman Empire they still had autonomy to rule over their lands, but the southern part which was put under the direct rule of the Ottoman Empire, prompted by the replacement of large parts of the local nobility with Ottoman landowners, centralized governance and the Ottoman taxation system, the population and the nobles, led principally by Gjergj Arianiti, revolted against the Ottomans.

During the early phases of the revolt, many land (timar) holders were killed or expelled. As the revolt spread, the nobles, whose holdings had been annexed by the Ottomans, returned to join the revolt and attempted to form alliances with the Holy Roman Empire. While the leaders of the revolt were successful in defeating successive Ottoman campaigns, they failed to capture many of the important towns in the Sanjak of Albania. Major combatants included members of the Dukagjini, Zenebishi, Thopia, Kastrioti and Arianiti families. In the initial phase, the rebels were successful in capturing some major towns such as Dagnum. Protracted sieges such as that of Gjirokastër, the capital of the Sanjak, gave the Ottoman army time to assemble large forces from other parts of the empire and to subdue the main revolt by the end of 1436. Because the rebel leaders acted autonomously without a central leadership, their lack of coordination of the revolt contributed greatly to their final defeat.[49] Ottoman forces conducted a number of massacres in the aftermath of the revolt.

Ottoman-Albanian Wars

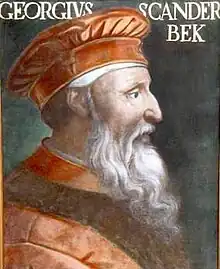

Many Albanians had been recruited into the Janissary corps, including the feudal heir George Kastrioti who was renamed Skanderbeg (Iskandar Bey) by his Turkish officers at Edirne. After the Ottoman defeat in the Battle of Niš at the hands of the Hungarians, Skanderbeg deserted in November 1443 and began a rebellion against the Ottoman Empire.[50]

After his desertion, Skanderbeg re-converted to Christianity and declared war against the Ottoman Empire,[50] which he led from 1443 to 1468. Skanderbeg summoned the Albanian princes to the Venetian-controlled town of Lezhë where they formed the League of Lezhë.[51] Gibbon reports that the "Albanians, a martial race, were unanimous to live and die with their hereditary prince", and that "in the assembly of the states of Epirus, Skanderbeg was elected general of the Turkish war and each of the allies engaged to furnish his respective proportion of men and money".[52] Under a red flag bearing Skanderbeg's heraldic emblem, an Albanian force held off Ottoman campaigns for twenty-five years and overcame a number of the major sieges: Siege of Krujë (1450), Second Siege of Krujë (1466–67), Third Siege of Krujë (1467) against forces led by the Ottoman sultans Murad II and Mehmed II. For 25 years Skanderbeg's army of around 10,000 men marched through Ottoman territory winning against consistently larger and better supplied Ottoman forces.[43]

Throughout his rebellion, Skanderbeg defeated the Ottomans in a number of battles, including Torvioll, Oranik, Otonetë, Modric, Ohrid and Mokra; with his most brilliant being in Albulena. However, Skanderbeg did not receive any of the help which had been promised to him by the popes or the Italian states, Venice, Naples and Milan. He died in 1468, leaving no clear successor. After his death the rebellion continued, but without its former success. The loyalties and alliances created and nurtured by Skanderbeg faltered and fell apart and the Ottomans reconquered the territory of Albania, culminating with the siege of Shkodra in 1479. However, some territories in Northern Albania remained under Venetian control. Shortly after the fall of the castles of northern Albania, many Albanians fled to neighbouring Italy, giving rise to the Arbëreshë communities still living in that country.

Skanderbeg's long struggle to keep Albania free became highly significant to the Albanian people, as it strengthened their solidarity, made them more conscious of their national identity, and served later as a great source of inspiration in their struggle for national unity, freedom and independence.[53]

Late Ottoman period

Upon the Ottomans return in 1479, a large number of Albanians fled to Italy, Egypt and other parts of the Ottoman Empire and Europe and maintained their Arbëresh identity. Many Albanians won fame and fortune as soldiers, administrators, and merchants in far-flung parts of the Empire. As the centuries passed, however, Ottoman rulers lost the capacity to command the loyalty of local pashas, which threatened stability in the region. The Ottoman rulers of the 19th century struggled to shore up central authority, introducing reforms aimed at harnessing unruly pashas and checking the spread of nationalist ideas. Albania would be a part of the Ottoman Empire until the early 20th century.

The Ottoman period that followed was characterized by a change in the landscape through a gradual modification of the settlements with the introduction of bazaars, military garrisons and mosques in many Albanian regions. Part of the Albanian population gradually converted to Islam, with many joining the Sufi Order of the Bektashi. Converting from Christianity to Islam brought considerable advantages, including access to Ottoman trade networks, bureaucratic positions and the army. As a result, many Albanians came to serve in the elite Janissary and the administrative Devşirme system. Among these were important historical figures, including Iljaz Hoxha, Hamza Kastrioti, Koca Davud Pasha, Zağanos Pasha, Köprülü Mehmed Pasha (head of the Köprülü family of Grand Viziers), the Bushati family, Sulejman Pasha, Edhem Pasha, Nezim Frakulla, Haxhi Shekreti, Hasan Zyko Kamberi, Ali Pasha of Gucia, Muhammad Ali ruler of Egypt,[54] Ali Pasha of Tepelena rose to become one of the most powerful Muslim Albanian rulers in western Rumelia. His diplomatic and administrative skills, his interest in modernist ideas and concepts, his popular religiousness, his religious neutrality, his win over the bands terrorizing the area, his ferocity and harshness in imposing law and order, and his looting practices towards persons and communities in order to increase his proceeds cause both the admiration and the criticism of his contemporaries. His court was in Ioannina, but the territory he governed incorporated most of Epirus and the western parts of Thessaly and Greek Macedonia in Northern Greece.

Many Albanians gained prominent positions in the Ottoman government, Albanians highly active during the Ottoman era and leaders such as Ali Pasha of Tepelena might have aided Husein Gradaščević. The Albanians proved generally faithful to Ottoman rule following the end of the resistance led by Skanderbeg, and accepted Islam more easily than their neighbors.[55]

Semi-independent Albanian Pashaliks

A period of semi-independence started during the mid 18th century. As Ottoman power began to decline in the 18th century, the central authority of the empire in Albania gave way to the local authority of autonomy-minded lords. The most successful of those lords were three generations of pashas of the Bushati family, who dominated most of northern Albania from 1757 to 1831, and Ali Pasha Tepelena of Janina (now Ioánnina, Greece), a brigand-turned-despot who ruled over southern Albania and northern Greece from 1788 to 1822.

Those pashas created separate states within the Ottoman state until they were overthrown by the sultan.[56][57]

Modern

National Renaissance

In the 1870s, the Sublime Porte's reforms aimed at checking the Ottoman Empire's disintegration had failed. The image of the "Turkish yoke" had become fixed in the nationalist mythologies and psyches of the empire's Balkan peoples and their march toward independence quickened. The Albanians, because of the higher degree of Islamic influence, their internal social divisions, and the fear that they would lose their Albanian-speaking territories to the emerging Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria, and Greece, were the last of the Balkan peoples to desire division from the Ottoman Empire.[58] With the rise of the Albanian National Awakening, Albanians regained a sense of statehood and engaged in military resistance against the Ottoman Empire as well as instigating a massive literary revival. Albanian émigrés in Bulgaria, Egypt, Italy, Romania and the United States supported the writing and distribution of Albanian textbooks and writings.

League of Prizren

In the second quarter of the 19th century, after the fall of the Albanian pashaliks and the Massacre of the Albanian Beys, an Albanian National Awakening took place and many revolts against the Ottoman Empire were organized. These revolts included the Albanian Revolts of 1833–1839, the Revolt of 1843–44, and the Revolt of 1847. A culmination of the Albanian National Awakening was the League of Prizren. The league was formed at a meeting of 47 Ottoman beys in Prizren on 18 June 1878. An initial position of the league was presented in a document known as Kararname. Through this document Albanian leaders emphasized their intention to preserve and maintain the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans by supporting the porte, and "to struggle in arms to defend the wholeness of the territories of Albania". In this early period, the League participated in battles against Montenegro and successfully wrestled control over Plav and Gusinje after brutal warfare with Montenegrin troops. In August 1878, the Congress of Berlin ordered a commission to determine the border between the Ottoman Empire and Montenegro. Finally, the Great Powers blockaded Ulcinj by sea and pressured the Ottoman authorities to bring the Albanians under control. Albanian diplomatic and military efforts were successful in wresting control of Epirus, however some lands were still ceded to Greece by 1881.

The League's founding figure Abdyl Frashëri influenced the League to demand autonomy and wage open war against the Ottomans. Faced with growing international pressure "to pacify" the refractory Albanians, the sultan dispatched a large army under Dervish Turgut Pasha to suppress the League of Prizren and deliver Ulcinj to Montenegro. The League of Prizren's leaders and their families were arrested and deported. Frashëri, who originally received a death sentence, was imprisoned until 1885 and exiled until his death seven years later. A similar league was established in 1899 in Peja by former League member Haxhi Zeka. The league ended its activity in 1900 after an armed conflict with the Ottoman forces. Zeka was assassinated by a Serbian agent Adem Zajmi in 1902.

Independence

The initial sparks of the First Balkan war in 1912 were ignited by the Albanian uprising between 1908 and 1910, which had the aim of opposing the Young Turk policies of consolidation of the Ottoman Empire.[59] Following the eventual weakening of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans, Serbia, Greece, and Bulgaria declared war, seizing the remaining Ottoman territory in Europe. The territory of Albania was occupied by Serbia in the north and Greece in the south, leaving only a patch of land around the southern coastal city of Vlora. The unsuccessful uprising of 1910, 1911 and the successful and final Albanian revolt in 1912, as well as the Serbian and Greek occupation and attempts to incorporate the land into their respective countries, led to a proclamation of independence by Ismail Qemali in Vlorë on 28 November 1912. The same day, Ismail Qemali waved the national flag of Albania, from the balcony of the Assembly of Vlorë, in the presence of hundreds of Albanians. This flag was sewn after Skanderbeg's principality flag, which had been used more than 500 years earlier.

Albanian independence was recognized by the Conference of London on 29 July 1913.[60][61] The Conference of London then delineated the border between Albania and its neighbors, leaving more than half of ethnic Albanians outside Albania. This population was largely divided between Montenegro and Serbia in the north and east (including what is now Kosovo and North Macedonia), and Greece in the south. A substantial number of Albanians thus came under Serbian rule.[62]

At the same time, an uprising in the country's south by local Greeks led to the formation of the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus in the southern provinces (1914).[63] The republic proved short-lived as Albania collapsed with the onset of World War I. Greece held the area between 1914 and 1916, and unsuccessfully tried to annex it in March 1916;[63] however in 1917 the Greeks were driven from the area by Italy, which took over most of Albania.[64] The Paris Peace Conference of 1919 awarded the area to Greece. However the area definitively reverted to Albanian control in November 1921, following Greece's defeat in the Greco-Turkish War.[65]

Principality of Albania

.svg.png.webp)

In supporting the independence of Albania, the Great Powers were assisted by Aubrey Herbert, a British MP who passionately advocated the Albanian cause in London. As a result, Herbert was offered the crown of Albania, but was dissuaded by the British Prime Minister, H. H. Asquith, from accepting. Instead the offer went to William of Wied, a German prince who accepted and became sovereign of the new Principality of Albania.[66]

The Principality was established on 21 February 1914. The Great Powers selected Prince William of Wied, a nephew of Queen Elisabeth of Romania to become the sovereign of the newly independent Albania. A formal offer was made by 18 Albanian delegates representing the 18 districts of Albania on 21 February 1914, an offer which he accepted. Outside of Albania William was styled prince, but in Albania he was referred to as Mbret (King) so as not to seem inferior to the King of Montenegro. This is the period when Albanian religions gained independence. The ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople recognized the autocephaly of the Albanian Orthodox Church after a meeting of the country's Albanian Orthodox congregations in Berat in August 1922. The most energetic reformers in Albania came from the Orthodox population who wanted to see Albania move quickly away from its Turkish-ruled past, during which Christians made up the underclass. Albania's conservative Sunni Muslim community broke its last ties with Constantinople in 1923, formally declaring that there had been no caliph since Muhammad himself and that Muslim Albanians pledged primary allegiance to their native country. The Muslims also banned polygamy and allowed women to choose whether or not they wanted to wear a veil. Upon termination of Albania from Turkey in 1912, as in all other fields, the customs administration continued its operation under legislation approved specifically for the procedure. After the new laws were issued for the operation of customs, its duty was 11% of the value of goods imported and 1% on the value of those exported.

The security was to be provided by a Gendarmerie commanded by Dutch officers. William left Albania on 3 September 1914 following a pan-Islamic revolt initiated by Essad Pasha Toptani and later headed by Haxhi Qamili, the latter the military commander of the "Muslim State of Central Albania" centered in Tirana. William never renounced his claim to the throne.[67]

World War I

World War I interrupted all government activities in Albania, while the country was split in a number of regional governments.[58] Political chaos engulfed Albania after the outbreak of World War I. The Albanian people split along religious and tribal lines after the prince's departure. Muslims demanded a Muslim prince and looked to Turkey as the protector of the privileges they had enjoyed. Other Albanians looked to Italy for support. Still others, including many beys and clan chiefs, recognized no superior authority.[68]

Prince William left Albania on 3 September 1914, as a result of the Peasant Revolt initiated by Essad Pasha and later taken over by Haxhi Qamili.[69] William subsequently joined the German army and served on the Eastern Front, but never renounced his claim to the throne.

In the country's south, the local Greek population revolted against the incorporation of the area into the new Albanian state and declared the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus at 28 February.[70][71]

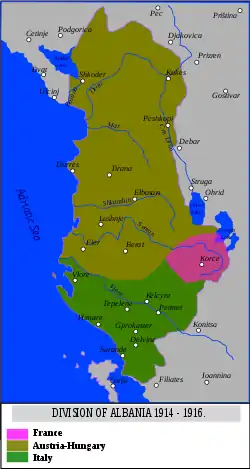

In late 1914, Greece occupied the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus, including Korçë and Gjirokastër. Italy occupied Vlorë, and Serbia and Montenegro occupied parts of northern Albania until a Central Powers offensive scattered the Serbian army, which was evacuated by the French to Thessaloniki. Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian forces then occupied about two-thirds of the country (Bulgarian occupation of Albania).

Under the secret Treaty of London signed in April 1915, Triple Entente powers promised Italy that it would gain Vlorë (Valona) and nearby lands and a protectorate over Albania in exchange for entering the war against Austria-Hungary. Serbia and Montenegro were promised much of northern Albania, and Greece was promised much of the country's southern half. The treaty left a tiny Albanian state that would be represented by Italy in its relations with the other major powers.

In September 1918, Entente forces broke through the Central Powers' lines north of Thessaloniki and within days Austro-Hungarian forces began to withdraw from Albania. On 2 October 1918 the city of Durrës was shelled on the orders of Louis Franchet d'Espèrey, during the Battle of Durazzo: according to d'Espèrey, the Port of Durrës, if not destroyed, would have served the evacuation of the Bulgarian and German armies, involved in World War I.[72]

When the war ended on 11 November 1918, Italy's army had occupied most of Albania; Serbia held much of the country's northern mountains; Greece occupied a sliver of land within Albania's 1913 borders; and French forces occupied Korçë and Shkodër as well as other regions with sizable Albanian populations.

Projects of partition in 1919–1920

Albanian soldiers during the Vlora war,1920.

After World War I, Albania was still under the occupation of Serbian and Italian forces. It was a rebellion of the respective populations of Northern and Southern Albania that pushed back the Serbs and Italians behind the recognized borders of Albania.

Albania's political confusion continued in the wake of World War I. The country lacked a single recognized government, and Albanians feared, with justification, that Italy, Yugoslavia, and Greece would succeed in extinguishing Albania's independence and carve up the country. Italian forces controlled Albanian political activity in the areas they occupied. The Serbs, who largely dictated Yugoslavia's foreign policy after World War I, strove to take over northern Albania, and the Greeks sought to control southern Albania.

A delegation sent by a postwar Albanian National Assembly that met at Durrës in December 1918 defended Albanian interests at the Paris Peace Conference, but the conference denied Albania official representation. The National Assembly, anxious to keep Albania intact, expressed willingness to accept Italian protection and even an Italian prince as a ruler so long as it would mean Albania did not lose territory. Serbian troops conducted actions in Albanian-populated border areas, while Albanian guerrillas operated in both Serbia and Montenegro.

In January 1920, at the Paris Peace Conference, negotiators from France, Britain, and Greece agreed to allow Albania to fall under Yugoslav, Italian, and Greek spheres of influence as a diplomatic expedient aimed at finding a compromising solution to the territorial conflicts between Italy and Yugoslavia.

Members of a second Albanian National Assembly held at Lushnjë in January 1920 rejected the partition plan and warned that Albanians would take up arms to defend their country's independence and territorial integrity.[73] The Lushnjë National Assembly appointed a four-man regency to rule the country. A bicameral parliament was also created, in which an elected lower chamber, the Chamber of Deputies (with one deputy for every 12,000 people in Albania and one for the Albanian community in the United States), appointed members of its own ranks to an upper chamber, the Senate. In February 1920, the government moved to Tirana, which became Albania's capital.

One month later, in March 1920, U.S. President Woodrow Wilson intervened to block the Paris agreement. The United States underscored its support for Albania's independence by recognizing an official Albanian representative to Washington, and in December the League of Nations recognized Albania's sovereignty by admitting it as a full member. The country's borders, however, remained unsettled following the Vlora War in which all territory (except Saseno island) under Italian control in Albania was relinquished to the Albanian state.

Albania achieved a degree of statehood after the First World War, in part because of the diplomatic intercession of the United States government. The country suffered from a debilitating lack of economic and social development, however, and its first years of independence were fraught with political instability. Unable to survive a predatory environment without a foreign protector, Albania became the object of tensions between Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which both sought to dominate the country.[74]

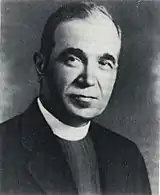

Zogu Government

Interwar Albanian governments appeared and disappeared in rapid succession. Between July and December 1921 alone, the premiership changed hands five times. The Popular Party's head, Xhafer Ypi, formed a government in December 1921 with Fan S. Noli as foreign minister and Ahmed Bey Zogu as internal affairs minister, but Noli resigned soon after Zogu resorted to repression in an attempt to disarm the lowland Albanians despite the fact that bearing arms was a traditional custom.

When the government's enemies attacked Tirana in early 1922, Zogu stayed in the capital and, with the support of the British ambassador, repulsed the assault. He took over the premiership later in the year and turned his back on the Popular Party by announcing his engagement to the daughter of Shefqet Verlaci, the Progressive Party leader.

Zogu's protégés organized themselves into the Government Party. Noli and other Western-oriented leaders formed the Opposition Party of Democrats, which attracted all of Zogu's many personal enemies, ideological opponents, and people left unrewarded by his political machine. Ideologically, the Democrats included a broad sweep of people who advocated everything from conservative Islam to Noli's dreams of rapid modernization.

Opposition to Zogu was formidable. Orthodox peasants in Albania's southern lowlands loathed Zogu because he supported the Muslim landowners' efforts to block land reform; Shkodër's citizens felt shortchanged because their city did not become Albania's capital, and nationalists were dissatisfied because Zogu's government did not press Albania's claims to Kosovo or speak up more energetically for the rights of the ethnic Albanian minorities in present-day Yugoslavia and Greece.

Zogu's party handily won elections for a National Assembly in early 1924. Zogu soon stepped aside, however, handing over the premiership to Verlaci in the wake of a financial scandal and an assassination attempt by a young radical that left Zogu wounded. The opposition withdrew from the assembly after the leader of a nationalist youth organization, Avni Rustemi, was murdered in the street outside the parliament building.[75]

June Revolution

.jpg.webp)

Noli's supporters blamed the Rustemi murder on Zogu's Mati clansmen, who continued to practice blood vengeance. After the walkout, discontent mounted, and in June 1924 a peasant-backed insurgency had won control of Tirana. Because few people were willing to risk their lives in its defense, the government's fall was remarkably simple and entailed practically little violence. According to US estimates, 20 people were killed and 35 were injured in the northern theatre, while 6 people were killed and 15 were injured in the southern theater. In fact, only Zogu and his meagre group put up any resistance at all. However, fundamental concerns remained unanswered, and Noli's power grab was unstable to say the least.[76] A far more unified group than Noli's was required to execute a new order; it also required crucial political and financial backing from overseas, as well as talented lawmakers prepared to make the necessary sacrifices and concessions. Noli formed his own administration, a small cabinet, on 16 June 1924, with representatives from all factions involved in the June rebellion, including the army, beys, liberals, progressives, and the Shkodra lobby. The Kosovo Committee was not a part of the government. The government cabinet consisted of:

- Fan Noli – Prime Minister

- Sulejman Delvina- Minister of Foreign Affairs

- Luigj Gurakuqi – Minister of Finance

- Stavro Vinjau – Minister of Education

- Kasëm Qafëzezi – Minister of War

- Rexhep Shala – Minister of Interior

- Qazim Koculi – Minister of Agriculture

- Xhemal Bushati – Minister without portfolio

Fan Noli, an idealist, rejected demands for new elections on the grounds that Albania needed a "paternal" government. On 19 June, Noli's coalition administration proposed a twenty-point reform program that, if completed, would have resulted in a country-wide revolution. Jacques calls the program "too radical," Austin calls it "a really ambitious program, ....had it been implemented, it would have led to a revolutionary change of country," and Fischer writes, "Every Western Democrat would be proud of Noli's program, but the Prime Minister lacked two crucial elements, without which no one could carry out such a long series of radical reforms: financial support and support from the governmental cabinet."[77]

Noli went on to say that once normalcy was restored, a national election would be held with secret and direct voting to decide the people's support. Noli planned to rule by decree for ten to twelve months, believing that the country's past elections did not reflect the desires of the Albanian people. Noli subsequently stated that his party "had the majority when we put the agrarian reforms on our programme. When it came to putting them in place, we were in the minority." The takeover of wealthy owners' property, particularly in central Albania, would be the principal source of additional land for the peasants. Each farmer was to receive 4–6 hectares of land for a household of up to 10 individuals. Families with more than 10 members would receive eight hectares of land.

Scaling back the bureaucracy, strengthening local government, assisting peasants, throwing Albania open to foreign investment, and improving the country's bleak transportation, public health, and education facilities filled out the Noli government's overly ambitious agenda. Noli encountered resistance to his program from people who had helped him oust Zogu, and he never attracted the foreign aid necessary to carry out his reform plans. Noli criticized the League of Nations for failing to settle the threat facing Albania on its land borders.

Under Fan Noli, the government set up a special tribunal that passed death sentences, in absentia, on Zogu, Verlaci, and others and confiscated their property.

In Yugoslavia Zogu recruited a mercenary army, and Belgrade furnished the Albanian leader with weapons, about 1,000 Yugoslav army regulars, and Russian White Emigres to mount an invasion that the Serbs hoped would bring them disputed areas along the border. After Noli decided to establish diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union, a bitter enemy of the Serbian ruling family, Belgrade began making wild allegations that Albania was about to embrace Bolshevism.

On 13 December 1924, Zogu's Yugoslav-backed army crossed into Albanian territory. By Christmas Eve, Zogu had reclaimed the capital, and Noli and his government had fled to Italy. The Noli government lasted just 6 months and a week.

First Republic

After defeating Fan Noli's government, Ahmet Zogu recalled the parliament, in order to find a solution for the uncrowned principality of Albania. The parliament quickly adopted a new constitution, proclaimed the first republic, and granted Zogu dictatorial powers that allowed him to appoint and dismiss ministers, veto legislation, and name all major administrative personnel and a third of the Senate. The Constitution provided for a parliamentary republic with a powerful president serving as head of state and government.

On 31 January, Zogu was elected president for a seven-year term. Opposition parties and civil liberties disappeared; opponents of the regime were murdered; and the press suffered strict censorship. Zogu ruled Albania using four military governors responsible to him alone. He appointed clan chieftains as reserve army officers who were kept on call to protect the regime against domestic or foreign threats.

Zogu, however, quickly turned his back on Belgrade and looked instead to Benito Mussolini's Italy for patronage.[74] Under Zogu, Albania joined the Italian coalition against Yugoslavia of Kingdom of Italy, Hungary, and Bulgaria in 1924–1927. After the United Kingdom's and France's political intervention in 1927 with the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the alliance crumbled.

Zogu maintained good relations with Benito Mussolini's fascist regime in Italy and supported Italy's foreign policy. He would be the first and only Albanian to hold the title of president until 1991.

Kingdom of Albania

In 1928, Zogu I secured the Parliament's consent to its own dissolution. Afterwards, Albania was declared a monarchy with Zogu I first as the Prime Minister, then as the President and at last as the King of Albania.[74] International recognition arrived forthwith. The new formed constitution abolished the Albanian Senate and created a unicameral parliament, but King Zog retained the dictatorial powers he had enjoyed as president. Zogu I remained a conservative, but initiated reforms. For example, in an attempt at social modernisation the custom of adding one's region to one's name was dropped. He also made donations of land to international organisations for the building of schools and hospitals.[78]

Soon after his incoronation, Zog broke off his engagement to Shefqet Verlaci's daughter, and Verlaci withdrew his support for the king and began plotting against him. Zog had accumulated a great number of enemies over the years, and the Albanian tradition of blood vengeance required them to try to kill him. Zog surrounded himself with guards and rarely appeared in public.[79] The king's loyalists disarmed all of Albania's tribes except for his own Mati tribesmen and their allies, the Dibra.[80] Nevertheless, on a visit to Vienna in 1931, Zog and his bodyguards fought a gun battle with would-be assassins Aziz Çami and Ndok Gjeloshi on the Opera House steps.[62]

Zog remained sensitive to steadily mounting disillusion with Italy's domination of Albania. The Albanian army, though always less than 15,000-strong, sapped the country's funds, and the Italians' monopoly on training the armed forces rankled public opinion. As a counterweight, Zog kept British officers in the Gendarmerie despite strong Italian pressure to remove them. In 1931, Zog openly stood up to the Italians, refusing to renew the 1926 First Treaty of Tirana.

Financial crisis

In 1932 and 1933, Albania could not make the interest payments on its loans from the Society for the Economic Development of Albania. In response, Rome turned up the pressure, demanding that Tirana name Italians to direct the Gendarmerie; join Italy in a customs union; grant Italy control of the country's sugar, telegraph, and electrical monopolies; teach the Italian language in all Albanian schools; and admit Italian colonists. Zog refused. Instead, he ordered the national budget slashed by 30 percent, dismissed the Italian military advisers, and nationalized Italian-run Roman Catholic schools in the northern part of the country. In 1934, Albania had signed trade agreements with Yugoslavia and Greece, and Mussolini had suspended all payments to Tirana. An Italian attempt to intimidate the Albanians by sending a fleet of warships to Albania failed because the Albanians only allowed the forces to land unarmed. Mussolini then attempted to buy off the Albanians. In 1935 he presented the Albanian government 3 million gold francs as a gift.[81]

Zog's success in defeating two local rebellions convinced Mussolini that the Italians had to reach a new agreement with the Albanian king. A government of young men led by Mehdi Frasheri, an enlightened Bektashi administrator, won a commitment from Italy to fulfill financial promises that Mussolini had made to Albania and to grant new loans for harbor improvements at Durrës and other projects that kept the Albanian government afloat. Soon Italians began taking positions in Albania's civil service, and Italian settlers were allowed into the country. Mussolini's forces overthrew King Zog when Italy invaded Albania in 1939.[74]

World War II

Starting in 1928, but especially during the Great Depression, the government of King Zog, which brought law and order to the country, began to increase the Italian influence more and more. Despite some significant resistance, especially at Durrës, Italy invaded Albania on 7 April 1939 and took control of the country, with the Italian Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini proclaiming Italy's figurehead King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy as King of Albania. The nation thus became one of the first to be occupied by the Axis Powers in World War II.[82]

As Hitler began his aggression against other European countries, Mussolini decided to occupy Albania as a means of competing with Hitler's territorial gains. Mussolini and the Italian Fascists saw Albania as a historical part of the Roman Empire, and the occupation was intended to fulfill Mussolini's dream of creating an Italian Empire. During the Italian occupation, Albania's population was subject to a policy of forced Italianization by the kingdom's Italian governors, in which the use of the Albanian language was discouraged in schools while the Italian language was promoted. At the same time, the colonization of Albania by Italians was encouraged.

Mussolini, in October 1940, used his Albanian base to launch an attack on Greece, which led to the defeat of the Italian forces and the Greek occupation of Southern Albania in what was seen by the Greeks as the liberation of Northern Epirus. While preparing for the Invasion of Russia, Hitler decided to attack Greece in December 1940 to prevent a British attack on his southern flank.[83]

Italian penetration

The Italian invasion of Albania in April 1939 was the conclusion of centuries of Italian interest in the country and twenty years of direct, if unsuccessful, economic and political participation in Albania, primarily under Benito Mussolini. The Straits of Otranto, which cross the Adriatic Sea and connect Albania and southern Italy by forty miles, have always operated as a bridge rather than a barrier, offering escape, cultural exchange, and an easy invasion path. Before World War I Italy and Austria-Hungary had been instrumental in the creation of an independent Albanian state. At the outbreak of war, Italy had seized the chance to occupy the southern half of Albania, to avoid it being captured by the Austro-Hungarians. That success did not last long, as post-war domestic problems, Albanian resistance, and pressure from United States President Woodrow Wilson, forced Italy to pull out in 1920.[84]

When Mussolini took power in Italy he turned with renewed interest to Albania. Italy began penetration of Albania's economy in 1925, when Albania agreed to allow it to exploit its mineral resources.[85] That was followed by the First Treaty of Tirana in 1926 and the Second Treaty of Tirana in 1927, whereby Italy and Albania entered into a defensive alliance.[85] The Albanian government and economy were subsidised by Italian loans, the Albanian army was trained by Italian military instructors, and Italian colonial settlement was encouraged. Despite strong Italian influence, Zog refused to completely give in to Italian pressure.[86] In 1931 he openly stood up to the Italians, refusing to renew the 1926 Treaty of Tirana. After Albania signed trade agreements with Yugoslavia and Greece in 1934, Mussolini made a failed attempt to intimidate the Albanians by sending a fleet of warships to Albania.[87]

As Nazi Germany annexed Austria and moved against Czechoslovakia, Italy saw itself becoming a second-rate member of the Axis.[88] The imminent birth of an Albanian royal child meanwhile threatened to give Zog a lasting dynasty. After Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia (15 March 1939) without notifying Mussolini in advance, the Italian dictator decided to proceed with his own annexation of Albania. Italy's King Victor Emmanuel III criticized the plan to take Albania as an unnecessary risk. Rome, however, delivered Tirana an ultimatum on 25 March 1939, demanding that it accede to Italy's occupation of Albania. Zog refused to accept money in exchange for countenancing a full Italian takeover and colonization of Albania.

Italian invasion

On 7 April Mussolini's troops invaded Albania. The operation was led by General Alfredo Guzzoni. The invasion force was divided into three groups, which were to land successively. The most important was the first group, which was divided in four columns, each assigned to a landing area at a harbor and an inland target on which to advance. Despite some stubborn resistance by some patriots, especially at Durrës, the Italians made short work of the Albanians.[88] Durrës was captured on 7 April, Tirana the following day, Shkodër and Gjirokastër on 9 April, and almost the entire country by 10 April.

Unwilling to become an Italian puppet, King Zog, his wife, Queen Geraldine Apponyi, and their infant son Leka fled to Greece and eventually to London. On 12 April, the Albanian parliament voted to depose Zog and unite the nation with Italy "in personal union" by offering the Albanian crown to Victor Emmanuel III.[89]

The parliament elected Albania's largest landowner, Shefqet Bej Verlaci, as Prime Minister. Verlaci additionally served as head of state for five days until Victor Emmanuel III formally accepted the Albanian crown in a ceremony at the Quirinale palace in Rome. Victor Emmanuel III appointed Francesco Jacomoni di San Savino, a former ambassador to Albania, to represent him in Albania as "Lieutenant-General of the King" (effectively a viceroy).

Albania under Italy

.svg.png.webp)

While Victor Emmanuel ruled as king, Shefqet Bej Verlaci served as the Prime Minister. Shefqet Verlaci controlled the day-to-day activities of the new Italian protectorate. On 3 December 1941, Shefqet Bej Verlaci was replaced as Prime Minister and Head of State by Mustafa Merlika Kruja.[90]

From the start, Albanian foreign affairs, customs, as well as natural resources came under direct control of Italy. The puppet Albanian Fascist Party became the ruling party of the country and the Fascists allowed Italian citizens to settle in Albania and to own land so that they could gradually transform it into Italian soil.

In October 1940, during the Greco-Italian War, Albania served as a staging-area for Italian dictator Benito Mussolini's unsuccessful invasion of Greece. Mussolini planned to invade Greece and other countries like Yugoslavia in the area to give Italy territorial control of most of the Mediterranean Sea coastline, as part of the Fascists objective of creating the objective of Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea") in which Italy would dominate the Mediterranean.

But, soon after the Italian invasion, the Greeks counter-attacked and a sizeable portion of Albania was in Greek hands (including the cities of Gjirokastër and Korçë). In April 1941, after Greece capitulated to the German forces, the Greek territorial gains in southern Albania returned to Italian command. Under Italian command came also large areas of Greece after the successful German invasion of Greece.

After the fall of Yugoslavia and Greece in April 1941, the Italian Fascists added to the territory of the Kingdom of Albania most of the Albanian-inhabited areas that had been previously given to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Albanian fascists claimed in May 1941 that nearly all the Albanian populated territories were united to Albania (see map). Even areas of northern Greece (Chameria) were administered by Albanians.[91] But this was even a consequence of borders that Italy and Germany agreed on when dividing their spheres of influence. Some small portions of territories with Albanian majority remained outside the new borders and contact between the two parts was practically impossible: the Albanian population under the Bulgarian rule was heavily oppressed.

Albania under Germany

After the surrender of the Italian Army in September 1943, Albania was occupied by the Germans.

With the collapse of the Mussolini government in line with the Allied invasion of Italy, Germany occupied Albania in September 1943, dropping paratroopers into Tirana before the Albanian guerrillas could take the capital. The German Army soon drove the guerrillas into the hills and to the south. The Nazi German government subsequently announced it would recognize the independence of a neutral Albania and set about organizing a new government, police and armed forces.

The Germans did not exert heavy-handed control over Albania's administration. Rather, they sought to gain popular support by backing causes popular with Albanians, especially the annexation of Kosovo. Many Balli Kombëtar units cooperated with the Germans against the communists and several Balli Kombëtar leaders held positions in the German-sponsored regime. Albanian collaborators, especially the Skanderbeg SS Division, also expelled and killed Serbs living in Kosovo. In December 1943, a third resistance organization, an anticommunist, anti-German royalist group known as Legaliteti, took shape in Albania's northern mountains. Led by Abaz Kupi, it largely consisted of Geg guerrillas, supplied mainly with weapons from the allies, who withdrew their support for the NLM after the communists renounced Albania's claims on Kosovo. The capital Tirana was liberated by the partisans on 17 November 1944 after a 20-day battle. The communist partizans entirely liberated Albania from German occupation on 29 November 1944, pursuing the German army until Višegrad, Bosnia (then Yugoslavia) in collaboration with the Yugoslav communist forces.

The Albanian partisans also liberated Kosovo, part of Montenegro, and southern Bosnia and Herzegovina. By November 1944, they had thrown out the Germans, being with Yugoslavia the only European nations to do so without any assistance from the allies. Enver Hoxha became the leader of the country by virtue of his position as Secretary General of the Albanian Communist Party. After having taken over power of the country, the Albanian communists launched a tremendous terror campaign, shooting intellectuals and arresting thousands of innocent people. Some died due to suffering torture.[92]

Albania was one of the only European country occupied by the Axis powers that ended World War II with a larger Jewish population than before the war.[93][94][95][96] Some 1,200 Jewish residents and refugees from other Balkan countries were hidden by Albanian families during World War II, according to official records.[97]

Albanian resistance in World War II

The National Liberation War of the Albanian people started with the Italian invasion in Albania on 7 April 1939 and ended on 28 November 1944. During the antifascist national liberation war, the Albanian people fought against Italy and Germany, which occupied the country. In the 1939–1941 period, the antifascist resistance was led by the National Front nationalist groups and later by the Communist Party.

Communist resistance

In October 1941, the small Albanian communist groups established in Tirana an Albanian Communist Party of 130 members under the leadership of Hoxha and an eleven-man Central Committee. The Albanian communists supported the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact, and did not participate in the antifascist struggle until Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. The party at first had little mass appeal, and even its youth organization netted recruits. In mid-1942, however, party leaders increased their popularity by calling the young peoples to fight for the liberation of their country, that was occupied by Fascist Italy.

This propaganda increased the number of new recruits by many young peoples eager for freedom. In September 1942, the party organized a popular front organization, the National Liberation Movement (NLM), from a number of resistance groups, including several that were strongly anticommunist. During the war, the NLM's communist-dominated partisans, in the form of the National Liberation Army, did not heed warnings from the Italian occupiers that there would be reprisals for guerrilla attacks. Partisan leaders, on the contrary, counted on using the lust for revenge such reprisals would elicit to win recruits.

The communists turned the so-called war of liberation into a civil war, especially after the discovery of the Dalmazzo-Kelcyra protocol, signed by the Balli Kombëtar. With the intention of organizing a partisan resistance, they called a general conference in Pezë on 16 September 1942 where the Albanian National Liberation Front was set up. The Front included nationalist groups, but it was dominated by communist partisans.

In December 1942, more Albanian nationalist groups were organized. Albanians fought against the Italians while, during Nazi German occupation, Balli Kombëtar allied itself with the Germans and clashed with Albanian communists, which continued their fight against Germans and Balli Kombëtar at the same time.

Nationalist resistance

A nationalist resistance to the Italian occupiers emerged in November 1942. Ali Këlcyra and Midhat Frashëri formed the Western-oriented Balli Kombëtar (National Front).[98] Balli Kombëtar was a movement that recruited supporters from both the large landowners and peasantry. It opposed King Zog's return and called for the creation of a republic and the introduction of some economic and social reforms. The Balli Kombëtar's leaders acted conservatively, however, fearing that the occupiers would carry out reprisals against them or confiscate the landowners' estates.

Communist revolution in Albania (1944)

The communist partisans regrouped and gained control of southern Albania in January 1944. In May they called a congress of members of the National Liberation Front (NLF), as the movement was by then called, at Përmet, which chose an Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation to act as Albania's administration and legislature. Hoxha became the chairman of the council's executive committee and the National Liberation Army's supreme commander.

The communist partisans defeated the last Balli Kombëtar forces in southern Albania by mid-summer 1944 and encountered only scattered resistance from the Balli Kombëtar and Legality when they entered central and northern Albania by the end of July. The British military mission urged the remnants of the nationalists not to oppose the communists' advance, and the Allies evacuated Kupi to Italy. Before the end of November, the main German troops had withdrawn from Tirana, and the communists took control of the capital by fighting what was left of the German army. A provisional government the communists had formed at Berat in October administered Albania with Enver Hoxha as prime minister.

Consequences of the war

The NLF's strong links with Yugoslavia's communists, who also enjoyed British military and diplomatic support, guaranteed that Belgrade would play a key role in Albania's postwar order. The Allies never recognized an Albanian government in exile or King Zog, nor did they ever raise the question of Albania or its borders at any of the major wartime conferences.

No reliable statistics on Albania's wartime losses exist, but the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration reported about 30,000 Albanian war dead, 200 destroyed villages, 18,000 destroyed houses, and about 100,000 people left homeless. Albanian official statistics claim somewhat higher losses. Furthermore, thousands of Chams (Tsams, Albanians living in Northern Greece) were driven out of Greece with the justification that they had collaborated with the Nazis.

Second Republic

Communism

A collection of communists moved quickly after the Second World War to subdue all potential political enemies in Albania, break the country's landowners and minuscule middle class, and isolate Albania from western powers in order to establish the People's Republic of Albania. In 1945, the communists had liquidated, discredited, or driven into exile most of the country's interwar elite. The Internal Affairs Minister, Koçi Xoxe, a pro-Yugoslav erstwhile tinsmith, presided over the trial and the execution of thousands of opposition politicians, clan chiefs, and members of former Albanian governments who were condemned as "war criminals."

Thousands of their family members were imprisoned for years in work camps and jails and later exiled for decades to miserable state farms built on reclaimed marshlands. The communists' consolidation of control also produced a shift in political power in Albania from the northern Ghegs to the southern Tosks. Most communist leaders were middle-class Tosks, Vlachs and Orthodox, and the party drew most of its recruits from Tosk-inhabited areas, while the Ghegs, with their centuries-old tradition of opposing authority, distrusted the new Albanian rulers and their alien Marxist doctrines.

In December 1945, Albanians elected a new People's Assembly, but only candidates from the Democratic Front (previously the National Liberation Movement then the National Liberation Front) appeared on the electoral lists, and the communists used propaganda and terror tactics to gag the opposition. Official ballot tallies showed that 92% of the electorate voted and that 93% of the voters chose the Democratic Front ticket. The assembly convened in January 1946, annulled the monarchy, and transformed Albania into a "people's republic."

The new leaders inherited an Albania plagued by many evils: widespread poverty, overwhelming illiteracy, gjakmarrje ("blood feuds"), epidemics of disease and blatant subjugation of women. In an attempt to eradicate these ills, the Communists have devised a programme of radical modernization. The first important measure was a rapid and uncompromising agrarian reform, which dismantled the large estates and distributed the plots to the peasants. This reform destroyed the powerful bey class. The government has also decided to nationalize industry, banks and all commercial and foreign properties. Shortly after the agrarian reform, the Albanian government began to collectivise agriculture, a process that will continue until 1967. In rural areas, the communist regime suppressed the centuries-old blood feud and patriarchal structure of the family and clans, thus destroying the semi-feudal Bajraktars class. The traditional role of women, confinement to the home and farm, changed dramatically when they achieved legal equality with men and became active participants in all areas of society.[99]

Enver Hoxha and Mehmet Shehu emerged as communist leaders in Albania, and are recognized by most western nations. They began to concentrate primarily on securing and maintaining their power base by killing all their political adversaries, and secondarily on preserving Albania's independence and reshaping the country according to the precepts of Stalinism so they could remain in power and develop the nation's economy. Political executions were common with between 5,000 and 25,000 killed in total under the communist regime.[100][101][102] According to the Albanian Association of Former Political Prisoners, 6,000 people were executed by the Stalinist regime from 1945 to 1991.[103] Albania became an ally of the Soviet Union, but this came to an end after 1956 over the advent of de-Stalinization, causing the Soviet-Albanian split. A strong political alliance with China followed, leading to several billion dollars in aid, which was curtailed after 1974, causing the Sino-Albanian split. China cut off aid in 1978 when Albania attacked its policies after the death of Chinese leader Mao Zedong. Large-scale purges of officials occurred during the 1970s.

During the period of socialist construction of Albania, the country saw rapid economic growth. For the first time, Albania was beginning to produce the major part of its own commodities domestically, which in some areas were able to compete in foreign markets. During the period of 1960 to 1970, the average annual rate of increase of Albania's national income was 29 percent higher than the world average and 56 percent higher than the European average. Also during this period, because of the monopolised socialist economy, Albania was the only country in the world that imposed no imposts or taxes on its people whatsoever.[104]

Enver Hoxha, who ruled Albania for four decades, died on 11 April 1985. Soon after Hoxha's death, voices for change emerged in the Albanian society and the government began to seek closer ties with the West in order to improve economic conditions. Eventually the new regime of Ramiz Alia introduced some liberalisation, and granting the freedom to travel abroad in 1990. The new government made efforts to improve ties with the outside world. The elections of March 1991 kept the former Communists in power, but a general strike and urban opposition led to the formation of a coalition cabinet that included non-Communists.[105]

In 1967, the authorities conducted a violent campaign to extinguish religious practice in Albania, claiming that religion had divided the Albanian nation and kept it mired in backwardness.[106] Student agitators combed the countryside, forcing Albanians to quit practicing their faith. Despite complaints, even by APL members, all churches, mosques, monasteries, and other religious institutions had been closed or converted into warehouses, gymnasiums, and workshops by year's end. A special decree abrogated the charters by which the country's main religious communities had operated.

Albania and Yugoslavia

Until Yugoslavia's expulsion from the Cominform in 1948, Albania acted like a Yugoslav satellite and the President of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz Tito aimed to use his choke hold on the Albanian party to incorporate the entire country into Yugoslavia.[107] After Germany's withdrawal from Kosovo in late 1944, Yugoslavia's communist partisans took possession of the province and committed retaliatory massacres against Albanians. Before the second World War, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia had supported transferring Kosovo to Albania, but Yugoslavia's postwar communist regime insisted on preserving the country's prewar borders.

In repudiating the 1943 Mukaj agreement under pressure from the Yugoslavs, Albania's communists had consented to restore Kosovo to Yugoslavia after the war. In January 1945, the two governments signed a treaty reincorporating Kosovo into Yugoslavia as an autonomous province. Shortly thereafter, Yugoslavia became the first country to recognize Albania's provisional government.

Relations between Albania and Yugoslavia declined, however, when the Albanians began complaining that the Yugoslavs were paying too little for Albanian raw materials and exploiting Albania through the joint stock companies. In addition, the Albanians sought investment funds to develop light industries and an oil refinery, while the Yugoslavs wanted the Albanians to concentrate on agriculture and raw-material extraction. The head of Albania's Economic Planning Commission and one of Hoxha's allies, Nako Spiru, became the leading critic of Yugoslavia's efforts to exert economic control over Albania. Tito distrusted Hoxha and the other intellectuals in the Albanian party and, through Xoxe and his loyalists, attempted to unseat them.

In 1947, Yugoslavia's leaders engineered an all-out offensive against anti-Yugoslav Albanian communists, including Hoxha and Spiru. In May, Tirana announced the arrest, trial, and conviction of nine People's Assembly members, all known for opposing Yugoslavia, on charges of antistate activities. A month later, the Communist Party of Yugoslavia's Central Committee accused Hoxha of following "independent" policies and turning the Albanian people against Yugoslavia.

Albania and the Soviet Union