History of Ukraine

Prehistoric Ukraine, as a part of the Pontic steppe in Eastern Europe, played an important role in Eurasian cultural events, including the spread of the Chalcolithic and Bronze Ages, Indo-European migrations, and the domestication of the horse.[1][2][3]

| History of Ukraine |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

A part of Scythia in antiquity, Ukraine was largely settled by Greuthungi, Getae, Goths, and Huns in the Migration Period, while southern parts of Ukraine were previously colonized by Greeks and then Romans. In the Early Middle Ages it was also a site of early Slavic expansion. The hinterland entered into written history with the establishment of the medieval state of Kievan Rus', which emerged as a powerful nation but disintegrated during the High Middle Ages, and was destroyed by the Mongol Empire in the 13th century.

During the 14th and 15th centuries, present-day Ukrainian territories came under the rule of four external powers: the Golden Horde, the Crimean Khanate, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. The latter two would then merge into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth following the Union of Krewo and Union of Lublin. Meanwhile, the Ottoman Empire emerged as a major regional power in and around the Black Sea, through protectorates like the Crimean Khanate, as well as directly-administered territory.

After a 1648 rebellion of the Cossacks against the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky agreed to the Treaty of Pereyaslav in January 1654. The exact nature of the relationship established by this treaty between the Cossack Hetmanate and Russia remains a matter of scholarly controversy.[4] The agreement precipitated the Russo-Polish War of 1654–67 and the failed Treaty of Hadiach, which would have formed a Polish–Lithuanian–Ruthenian Commonwealth. In consequence, by the Treaty of Perpetual Peace, signed in 1686, the eastern portion of Ukraine (east of the Dnieper River) was to come under Russian rule,[5] 146,000 rubles were to be paid to Poland as compensation for the loss of right-bank Ukraine,[6] and the parties agreed not to sign a separate treaty with the Ottoman Empire.[6] The treaty was strongly opposed in Poland and was not ratified by the Polish–Lithuanian Sejm until 1710.[6][7] The legal legitimacy of its ratification has been disputed.[8] According to Jacek Staszewski, the treaty was not confirmed by a resolution of the Sejm until its 1764 session.[9]

During the Great Northern War, Hetman Ivan Mazepa allied with Charles XII of Sweden in 1708. However, the Great Frost of 1709 greatly weakened the Swedish army. Following the Battle of Poltava later in 1709, there was a diminishment in Hetmanate power, culminating with the disestablishment of the Cossack Hetmanate in the 1760s and the destruction of the Zaporozhian Sich in the 1770s. Following the Partitions of Poland (1772–1795) and the Russian conquest of the Crimean Khanate, the Russian Empire and Habsburg Austria were in control of all the territories that constitute present-day Ukraine for over a hundred years. Ukrainian nationalism developed in the 19th century.

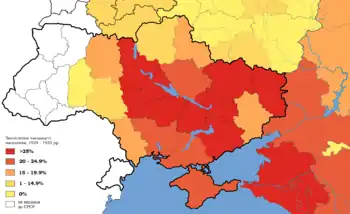

A chaotic period of warfare ensued after the Russian Revolutions of 1917, as well as a simultaneous war in the former Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria following the dissolution of the Habsburg monarchy after World War I. The Soviet–Ukrainian War (1917–1921) followed, in which the Bolshevik Red Army established control in late 1919.[10] The Ukrainian Bolsheviks, who had defeated the national government in Kyiv, established the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which on 30 December 1922 became one of the founding republics of the Soviet Union. Initial Soviet policy on the Ukrainian language and Ukrainian culture made Ukrainian the official language of administration and schools. Policy in the 1930s turned to Russification. In 1932 and 1933, millions of people in Ukraine, mostly peasants, starved to death in a devastating famine, known as the Holodomor. It is estimated that 6 to 8 million people died from hunger in the Soviet Union during this period, of whom 4 to 5 million were Ukrainians.[11]

After the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany invaded Poland in September 1939, the Ukrainian SSR's territory expanded westward. Axis armies occupied Ukraine from 1941 to 1944. During World War II, elements of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army fought for Ukrainian independence against both Germany and the Soviet Union, while other elements collaborated with the Nazis, assisting them in carrying out the Holocaust in Ukraine and their oppression of Poles. In 1953, Nikita Khrushchev, a Russian, succeeded as head of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and enabled a Ukrainian revival, and in 1954 the republic expanded to the south with the transfer of Crimea from Russia. Nevertheless, political repressions against poets, historians and other intellectuals continued, as in all other parts of the USSR.

Ukraine became independent again when the Soviet Union dissolved in 1991. This started a period of transition to a market economy, in which Ukraine suffered an eight-year recession.[12] Subsequently however, the economy experienced a high increase in GDP growth until it plunged during the Great Recession.[13]

A prolonged political crisis began on 21 November 2013, when president Viktor Yanukovych suspended preparations for the implementation of an association agreement with the European Union, instead choosing to seek closer ties with Russia. This decision resulted in the Euromaidan protests and later, the Revolution of Dignity. Yanukovych was then impeached by the Ukrainian parliament in February 2014. On 20 February, the Russo-Ukrainian War began when Russian forces entered Crimea. Soon after, pro-Russian unrest enveloped the largely Russophone eastern and southern regions of Ukraine, from where Yanukovych had drawn most of his support. A referendum in the largely ethnic Russian Ukrainian autonomous region of Crimea was held and Crimea was de facto annexed by Russia on 18 March 2014. The War in Donbas began in Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts of Ukraine involving pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian Ukrainians and Russian mercenaries. The war stalled until 24 February 2022, when Russia launched a major invasion of much of the country.

Prehistory

Paleolithic period

Settlement in Ukraine by members of the genus Homo has been documented into distant Paleolithic prehistory. The Neanderthals are associated with the Molodova archaeological sites (45,000–43,000 BC), which include a mammoth bone dwelling.[14][15] The earliest documented evidence of modern humans are found in Gravettian settlements dating to 32,000 BC in the Buran-Kaya cave site of the Crimean Mountains.[16][17]

Neolithic and Bronze Age

In the late Neolithic times, the Cucuteni-Trypillian Culture flourished from about 4,500–3,000 BC.[18] The Copper Age people of the Cucuteni-Trypillian Culture resided in the western part, and the Sredny Stog Culture further east, succeeded by the early Bronze Age Yamna ("Kurgan") culture of the Pontic steppes, and by the Catacomb culture in the 3rd millennium BC.

Iron Age and classical antiquity

Scythian settlement, Greek colonization, and Roman domination

During the Iron Age, these peoples were followed by the Dacians as well as nomadic peoples like the Cimmerians (archaeological Novocherkassk culture), Scythians and Sarmatians. The Scythian kingdom existed here from 750 to 250 BC.[19] In the Scythian campaign of Darius the Great in 513 BC, the Achaemenid Persian army subjugated several Thracian peoples, and virtually all other regions along the European part of the Black Sea, such as parts of nowadays Bulgaria, Romania, Ukraine, and Russia, before it returned to Asia Minor.[20][21] Greeks colonized Crimea and other coastal areas of Ukraine in the 7th or 6th century BC during the Archaic period.[22] The culturally Greek Bosporan Kingdom thrived until it was invaded and occupied by the Goths and Huns in the 4th century AD.[23] From 62 to 68 AD the Roman Empire briefly annexed the kingdom under Emperor Nero when he deposed the Bosporan king Tiberius Julius Cotys I.[24] Afterwards the Bosporan Kingdom was made into a Roman client state with a Roman military presence during the middle of the 1st century AD.[25][26]

Arrival of the Goths and Huns

In the 3rd century AD, the Goths migrated into the lands of modern Ukraine around 250–375 AD, which they called Oium, corresponding to the archaeological Chernyakhov culture.[27] The Ostrogoths stayed in the area but came under the sway of the Huns from the 370s. North of the Ostrogothic kingdom was the Kyiv culture, flourishing from the 2nd–5th centuries, when it was also overrun by the Huns. After they helped defeat the Huns at the battle of Nedao in 454, the Ostrogoths were allowed by the Romans to settle in Pannonia. Along with other ancient Greek colonies founded in the 6th century BC on the northeastern shore of the Black Sea, the colonies of Tyras, Olbia, and Hermonassa continued as Roman and Byzantine (Eastern Roman) cities until the 6th century AD. Gothic influence waned by the end of the 5th century AD, when the Eastern Roman Empire reaffirmed its control and influence over the region.[28] The Hunnic king Gordas ruled the Bosporan kingdom in the early 6th century AD and maintained good relations with Eastern Roman emperor Justinian I, but the latter invaded and occupied the country once Gordas was killed in a revolt in 527 AD.[29] As late as the 12th century AD the Eastern Roman emperors claimed dominion over the territory of Cimmerian Bosporos.[30]

Early Slavs

With the power vacuum created with the end of Hunnic and Gothic rule, Early Slavs, in the aftermath of the Kyiv culture, began to expand over much of the territory that is now Ukraine during the 5th century, and beyond to the Balkans from the 6th century. Although the origins of the Early Slavs are not known for certain, many theories suggest they may have originated near Polesia.[31]

In the 5th and 6th centuries, the Antes Union (a tribal federation) is generally regarded to have been located in the territory of what is now Ukraine. The Antes were the ancestors of Ukrainians: White Croats, Severians, Polans, Drevlyans, Dulebes, Ulichians, and Tiverians. Migrations from Ukraine throughout the Balkans established many South Slavic nations. Northern migrations, reaching almost to Lake Ilmen, led to the emergence of the Ilmen Slavs, Krivichs, and Radimichs, the groups ancestral to the Russians. After a Pannonian Avar raid in 602 and the collapse of the Antes Union, most of these peoples survived as separate tribes until the beginning of the second millennium.[32]

Middle Ages

Early Middle Ages

In the 7th century, the territory of modern Ukraine was the core of the state of the Bulgars (often referred to as Old Great Bulgaria) with its capital city of Phanagoria. At the end of the 7th century, most Bulgar tribes migrated in several directions and the remains of their state were absorbed by the Khazars, a semi-nomadic people from Central Asia.[27]

The Khazars founded the Khazar kingdom near the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus. The kingdom included western Kazakhstan and parts of Crimea, eastern Ukraine, southern Russia and Azerbaijan. The Khazars dominated enough of the Pontic–Caspian steppe such that there was a Pax Khazarica in terms of trade, which allowed long distance trade to occur in safety, including groups like the Radhanite Jews who traded as far as China to Tabriz, as well as the trade networks that surrounded Volga Bulgaria. This attracted other traders such as the Vikings in the Viking Age who would found Kievan Rus'.

Kievan Rus'

It is uncertain how the state of Kievan Rus' came to be, but the Varangian nobleman Oleh the Wise is generally credited with having established a principality at the city of Kyiv somewhere around the year 880.[lower-alpha 1] Kyiv had already been established, but its origins are nebulous as well. According to archaeologists and historians such as Petro Tolochko (2007), Slavic settlement existed from the end of the 5th century in the area that later developed into the city.[34] Kyiv may have paid tribute to the Khazars before Oleh conquered it.[35][36] Tolochko and other scholars also theorise that 'Kyiv was not the center of any particular tribe but the intertribal center of a vast realm'; critical analysis of the Primary Chronicle, De Administrando Imperio and other sources suggests it may have been a cosmopolitan urban home to Slavic and non-Slavic groups, such as Scandinavian Varangians and Finno-Ugric peoples.[37] Slavic peoples that were reportedly native to Ukraine included Polans (or Polianians), Drevlyans, Severians, Ulichs, Tiverians, White Croats and Dulebes, but their precise identity and interrelationships are difficult to establish and verify, as the sources are vague, contradictory and at times inaccurate.[38]

.jpg.webp)

In the 10th and 11th century, Kyiv became one of the richest commercial centres of Europe, and the Kievan Rus' empire around it steadily expanded.[39] Initially a benefactor of the worship of Slavic deities such as Perun, Volodimer I converted to Orthodox Christianity in the 980s, tying the realm into a political and ecclesiastical alliance with the Byzantine Empire.[39] The reign of Yaroslav the Wise (r. 1019–1054) is generally regarded its zenith; Kievan Rus' was the most prosperous and powerful empire within Christendom.[39] Kievan Rus' was never a fully centralized state, but rather a loose aggregation of principalities ruled by members of the Rurik dynasty.[40] In the Late Middle Ages, it became known in the rest of Europe as Ruthenia (the Latin name for Rus'), especially for western principalities of Rus' after the Mongol invasion.

Christianisation

While Christianity had made headway into the territory of modern Ukraine before the first ecumenical council, the Council of Nicaea (325) (particularly along the Black Sea coast, with the clearest evidence being the Christianization of the Crimean Goths) and, in western Ukraine during the time of the Empire of Great Moravia, the formal governmental acceptance of Christianity in Rus' occurred in 988. The major promoter of the Christianization of Kievan Rus' was the Grand-Duke Vladimir the Great whose grandmother, Princess Olga, was a Christian. Later the Kievan ruler, Yaroslav I promulgated the Russkaya Pravda (Truth of Rus') which continued through the Lithuanian period of Rus'.

In 1322, Pope John XXII established a diocese in Caffa (modern day Feodosia), which broke apart the Diocese of Khanbaliq (modern day Beijing), the only Catholic presence in the Mongol lands. For a few centuries it was the main see over an area from the Balkans to Sarai.[41]

Disintegration of Kievan Rus' and Mongol invasion

Conflict among the various principalities of Rus', in spite of the efforts of Grand Prince Vladimir Monomakh, led to decline, beginning in the 12th century. In Rus' propria, the Kyiv region, the nascent Rus' principalities of Halych and Volhynia extended their rule. In the north, the name of Moscow appeared in the historical record in the Principality of Suzdal, which gave rise to the nation of Russia. In the north-west, the Principality of Polotsk increasingly asserted the autonomy of Belarus. Kyiv was sacked by the Principality of Vladimir (1169) in the power struggle between princes and later by Cuman and Mongol raiders in the 12th and 13th centuries, respectively. Subsequently, all principalities of present-day Ukraine acknowledged dependence upon the Mongols (1239–1240). In 1240, the Mongols sacked Kyiv, and many people fled to other countries.

Galicia-Volhynia

A successor state to the Kievan Rus' on part of the territory of today's Ukraine was the Principality of Galicia-Volhynia. Previously, Vladimir the Great had established the cities of Halych and Volodymyr as regional capitals. The region was inhabited by the Dulebe, Tiverian and White Croat tribes. Initially both Volhynia and Galicia were separate principalities, ruled by descendants of Yaroslav the Wise (Galicia by Rostislavich dynasty, and Volhynia initially by Igorevich and eventually by Iziaslavich dynasty).[42] During the rule Yaroslav Osmomysl (1153-1187) Galicia extended to the Black Sea.[42] Rulers of both principalites were trying to extend the rule over another. It was finally achieved by Roman the Great (1197-1205), who not only united both Galicia and Volhynia, but also extended his rule to Kyiv for a short period of time.

His death was followed by a period of turmoil that lasted until his son Daniel regained the throne in 1238. Daniel managed to rebuild his father's state, including Kiev. Daniel paid tribute to the Mongol khan, who appointed him baskak, responsible for collecting tribute from the Rus princes. In 1253 he was crowned by a papal delegation "King of Rus'" (Latin: rex Russiae); previously, the rulers of Rus' were termed "Grand Dukes" or "Princes."

Late Middle Ages

From the 13th century, the many parts of the coast of present-day Ukraine were dominated by the Republic of Genoa, which created numerous colonies around the Black Sea, most of them situated in today's Odesa Oblast. The Genoese colonies were well fortified, and there were garrisons in the fortresses and were used by the Genoese republic mainly for the purpose of dominating trade in the Black Sea. Genoa's dominance in the region would last until the 15th century.[43][44][45]

During the 14th century, Poland and Lithuania fought wars against the Mongol invaders, and eventually most of Ukraine passed to the rule of Poland and Lithuania. More particularly, Red Ruthenia, and part of Volhynia and Podolia became part of Poland. King of Poland adopted the tile of "lord and heir of Ruthenia" (Latin: Russiae dominus et Heres[46]). Lithuania took control of Polotsk, Volhynia, Chernihiv, and Kyiv following Battle of Blue Waters (1362/63), and the rulers of Lithuania then adopted the title of ruler of Rus'.

After the downfall of Kyivan Rus' and Galicia–Volhynia, their political, cultural and religious life continued under Lithuanian control.[47] Ruthenian aristocrats, for example, the Olelkovich, joined the governing class of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as members of the grand duke's privy council, senior military leaders, and administrators.[47] Despite Lithuanian being the native language of the ruling class, the main written languages within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania were Latin, Old Church Slavonic, as well as Ruthenian, with East Slavonic Chancery being replaced by Polish in the early modern period.[48]

Eventually, Poland took control of the southwestern region. Following the union between Poland and Lithuania, Poles, Germans, Lithuanians and Jews migrated to the region, forcing Ukrainians out of positions of power they shared with Lithuanians, with more Ukrainians being forced into Central Ukraine as a result of Polish migration, polonization, and other forms of oppression against Ukraine and Ukrainians, all of which started to fully take form.

In 1490, due to increased oppression of Ukrainians at the hands of the Polish, a series of successful rebellions was led by Ukrainian Petro Mukha, joined by other Ukrainians, such as early Cossacks and Hutsuls, in addition to Moldavians (Romanians). Known as Mukha's Rebellion, this series of battles was supported by the Moldavian prince Stephen the Great, and it is one of the earliest known uprisings of Ukrainians against Polish oppression. These rebellions saw the capture of several cities of Pokuttya, and reached as far west as Lviv, but without capturing the latter.[49]

The 15th-century decline of the Golden Horde enabled the foundation of the Crimean Khanate, which occupied present-day Black Sea shores and southern steppes of Ukraine. Until the late 18th century, the Crimean Khanate maintained a massive slave trade with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East,[50] exporting about 2 million slaves from Russia and Ukraine over the period 1500–1700.[51] It remained a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire until 1774, when it was finally dissolved by the Russian Empire in 1783.

Early modern period

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

After the Union of Lublin in 1569 and the formation of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth Ukraine fell under the Polish administration, becoming part of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. The period immediately following the creation of the Commonwealth saw a huge revitalisation in colonisation efforts. Many new cities and villages were founded & links between different Ukrainian regions, such as Halych Land and Volhynia were greatly extended.[52]

New schools spread the ideas of the Renaissance; Polish peasants arrived in great numbers and quickly became mixed with the local population; during this time, most Ukrainian nobles became polonised and converted to Catholicism, and while most Ruthenian-speaking peasants remained within the Eastern Orthodox Church, social tension rose. Some of the polonized mobility would heavily shape Polish culture, for eample, Stanisław Orzechowski.

Ruthenian peasants who fled efforts to force them into serfdom came to be known as Cossacks and earned a reputation for their fierce martial spirit. Some Cossacks were enlisted by the Commonwealth as soldiers to protect the southeastern borders of Commonwealth from Tatars or took part in campaigns abroad (like Petro Konashevych-Sahaidachny in the battle of Khotyn 1621). Cossack units were also active in wars between the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Tsardom of Russia. Despite the Cossack's military usefulness, the Commonwealth, dominated by its nobility, refused to grant them any significant autonomy, instead attempting to turn most of the Cossack population into serfs. This led to an increasing number of Cossack rebellions aimed at the Commonwealth.

| Voivodeship | Square kilometers | Population (est.) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Galicia | 45,000 | 446,000 | |

| Volhynia | 42,000 | 294,000 | |

| Podilia | 19,000 | 98,000 | |

| Bratslav | 35,000 | 311,000 | |

| Kyiv | 117,000 | 234,000 | |

| Belz (two regions) | Kholm | 19,000 | 133,000 |

| Pidliassia | 10,000 | 233,000 | |

Cossack era

%252C_cartographer.jpg.webp)

The 1648 Ukrainian Cossack (Kozak) rebellion or Khmelnytsky Uprising, which started an era known as the Ruin (in Polish history as the Deluge), undermined the foundations and stability of the Commonwealth. The nascent Cossack state, the Cossack Hetmanate,[54] usually viewed as precursor of Ukraine,[54] found itself in a three-sided military and diplomatic rivalry with the Ottoman Turks, who controlled the Tatars to the south, the Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania, and the Tsardom of Russia to the East.

The Zaporozhian Host, in order to leave the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, sought a treaty of protection with Russia in 1654.[54] This agreement was known as the Pereiaslav Agreement.[54] Commonwealth authorities then sought compromise with the Ukrainian Cossack state by signing the Treaty of Hadiach in 1658, but—after thirteen years of incessant warfare—the agreement was later superseded by the 1667 Polish–Russian Truce of Andrusovo, which divided Ukrainian territory between the Commonwealth and Russia. Under Russia, the Cossacks initially retained official autonomy in the Hetmanate.[54] For a time, they also maintained a semi-independent republic in Zaporizhzhia and a colony on the Russian frontier in Sloboda Ukraine.

In 1686, the Metropolitanate of Kyiv was annexed by the Moscow Patriarchate through the Synodal Letter of the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Dionysius IV.

Russian Empire and Austria-Hungary

During subsequent decades, Tsarist rule over central Ukraine gradually replaced 'protection'. Sporadic Cossack uprisings were now aimed at the Russian authorities, but eventually petered out by the late 18th century, following the destruction of entire Cossack hosts. After the Partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and 1795, the extreme west of Ukraine fell under the control of the Austrians, with the rest becoming a part of the Russian Empire. As a result of the Russo-Turkish Wars, the Ottoman Empire's control receded from south-central Ukraine, while the rule of Hungary over the Transcarpathian region continued. Ukrainian writers and intellectuals were inspired by the nationalistic spirit stirring other European peoples existing under other imperial governments and became determined to revive the Ukrainian linguistic and cultural traditions and re-establish a Ukrainian nation-state, a movement that became known as Ukrainophilism.

Russia, fearing separatism, imposed strict limits on attempts to elevate the Ukrainian language and culture, even banning its use and study: in 1863, the Valuev Circular banned the use of Ukrainian in religious and educational literature, in 1876, the Ems Ukaz outlawed Ukrainian-language publications outright, as well as the import of texts published abroad in Ukrainian, the use of Ukrainian in theatrical productions and public readings, the use of Ukrainian in schools.[55] The Russophile policies of Russification and Panslavism led to an exodus of a number of Ukrainian intellectuals into Western Ukraine. However, many Ukrainians accepted their fate in the Russian Empire and some were able to achieve great success there.

The fate of the Ukrainians was far different under the Austrian Empire where they found themselves in the pawn position of the Russian–Austrian power struggle for Central and Southern Europe. Unlike in Russia, most of the elite that ruled Galicia were of Austrian or Polish descent, with the Ruthenians being almost exclusively kept in peasantry. During the 19th century, Russophilia was a common occurrence among the Slavic population, but the mass exodus of Ukrainian intellectuals escaping from Russian repression in Eastern Ukraine, as well as the intervention of Austrian authorities, caused the movement to be replaced by Ukrainophilia, which would then cross over into the Russian Empire. With the start of World War I, all those supporting Russia were rounded up by Austrian forces and held in a concentration camp at Talerhof where many died.

Modern history

17th and 18th-century Ukraine

Ukraine emerges as the concept of a nation, and the Ukrainians as a nationality, with the Ukrainian National Revival in the mid-18th century, in the wake of the peasant revolt of 1768/1769 and the eventual partition of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Galicia fell to the Austrian Empire, and the rest of Ukraine to the Russian Empire.

While right-bank Ukraine belonged to the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth until late 1793, left-bank Ukraine had been incorporated into Tsardom of Russia in 1667 (under the Treaty of Andrusovo). In 1672, Podolia was occupied by the Turkish Ottoman Empire, while Kyiv and Braclav came under the control of Hetman Petro Doroshenko until 1681, when they were also captured by the Turks, but in 1699 the Treaty of Karlowitz returned those lands to the Commonwealth.

Most of Ukraine fell to the Russian Empire under the reign of Catherine the Great; the Crimean Khanate was annexed by Russia in 1783, following the Emigration of Christians from Crimea in 1778, and in 1793 right-bank Ukraine was annexed by Russia in the Second Partition of Poland.[56]

Ukrainian writers and intellectuals were inspired by the nationalistic spirit stirring other European peoples existing under other imperial governments. Russia, fearing separatism, imposed strict limits on attempts to elevate the Ukrainian language and culture, even banning its use and study. The Russophile policies of Russification and Panslavism led to an exodus of a number some Ukrainian intellectuals into Western Ukraine, while others embraced a Pan-Slavic or Russian identity.

19th century

Ukraine under the reign of Alexander I (1801–1825) saw Russian presence only involving the imperial army and its bureaucracy, but by the reign of Nicholas I (1825–1855), Russia had by then established a centralized administration in Ukraine. After suppressing the November Uprising of 1830, the tsarist regime instituted Russification policies on the Right Bank.[57]

The 2.4 million Ukrainians under the Habsburg Empire lived in eastern Galicia and consisted mainly of the peasantry (95%) with the remainder being priestly families. The Galician nobility were majoritively Poles or Polonized Ukrainians. Development here lagged behind Russian-ruled Ukraine and was one of the poorest regions in Europe.[57]

The rise in national consciousness arose in the 19th century, with representation of the intelligentsia declining among the nobles and increasing towards commoners and peasants, they saw a process of nation-building to improve national rights and social justice but was uncovered soon after by the tsarist authorities. After the 1848 revolutions, Ukrainians established the Supreme Ruthenian Council, demanding autonomy, they also opened the first Ukrainian-language newspaper (Zoria halytska). The 1861 emancipation greatly impacted Ukrainians as 42% of them were serfs. During the late 19th century, heavy taxes, rapid population growth and lack of land impoverished the peasantry. However the steppe regions managed to produce 20% of world production of wheat and 80% of the empire's sugar. Later, industrialization arrived with the first railway track constructed in 1866. Ukraine's economy by now was integrated into the imperial system and it saw much urban development.[57]

20th century

.jpg.webp)

Russian Revolution and War of Independence

Historian Paul Kubicek says:

- Between 1917 and 1920, several entities that aspired to be independent Ukrainian states came into existence. This period, however, was extremely chaotic, characterized by revolution, international and civil war, and lack of strong central authority. Many factions competed for power in the area that is today’s Ukraine, and not all groups desired a separate Ukrainian state. Ultimately, Ukrainian independence was short-lived, as most Ukrainian lands were incorporated into the Soviet Union and the remainder, in western Ukraine, was divided among Poland, Czechoslovakia, and Romania.[58]

Canadian scholar Orest Subtelny says:

- In 1919 total chaos engulfed Ukraine. Indeed, in the modern history of Europe no country experienced such complete anarchy, bitter civil strife, and total collapse of authority as did Ukraine at this time. Six different armies-– those of the Ukrainians, the Bolsheviks, the Whites, the Entente [French], the Poles and the anarchists – operated on its territory. Kyiv changed hands five times in less than a year. Cities and regions were cut off from each other by the numerous fronts. Communications with the outside world broke down almost completely. The starving cities emptied as people moved into the countryside in their search for food.[59]

The Ukrainian War of Independence of 1917 to 1921 produced the Makhnovshchina, Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (in 1919 merged from the Ukrainian People's Republic and West Ukrainian People's Republic) which was quickly subsumed in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet famine of 1930–33, now known as the Holodomor, left millions dead in the Soviet Union, the majority of them Ukrainians not only in Ukraine but also in Kuban and former Don Cossack lands.[60][61]

Second World War

The Second World War began in September 1939, when Hitler and Stalin invaded Poland, the Soviet Union taking most of Eastern Poland. Nazi Germany with its allies invaded the Soviet Union in 1941. Between 4.5 and 6 million Ukrainians fought in the Soviet Army against the Nazis.[62] Some Ukrainians initially regarded the Wehrmacht soldiers as liberators from Soviet rule, while others formed a partisan movement. Some elements of the Ukrainian nationalist underground formed a Ukrainian Insurgent Army that fought both Soviet forces and the Nazis. Others collaborated with the Germans. The pro-Polish trend in the Ukrainian national movement, declaring loyalty to the Second Polish Republic and in return demanding autonomy for Ukrainians (e.g. Ukrainian National Democratic Alliance), became marginalized, mainly due to its rejection by the Polish side, where supporters of forced assimilation of Ukrainians into Polish culture dominated.[63] Some 1.5 million Jews were murdered by the Nazis during their occupation.[64] In Volhynia, Ukrainian fighters committed a massacre against up to 100,000 Polish civilians.[65] Residual small groups of the UPA-partizans acted near the Polish and Soviet border as long as to the 1950s.[66] Galicia, Volhynia, South Bessarabia, Northern Bukovina, and Carpathian Ruthenia that were annexed as a result of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact in 1939 were added to the Ukrainian SSR.

After World War II, some amendments to the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR were accepted, which allowed it to act as a separate subject of international law in some cases and to a certain extent, remaining a part of the Soviet Union at the same time. In particular, these amendments allowed the Ukrainian SSR to become one of the founding members of the United Nations (UN) together with the Soviet Union and the Byelorussian SSR. This was part of a deal with the United States to ensure a degree of balance in the General Assembly, which, the USSR opined, was unbalanced in favor of the Western Bloc. In its capacity as a member of the UN, the Ukrainian SSR was an elected member of the United Nations Security Council in 1948–1949 and 1984–1985. The Crimean Oblast was transferred from the RSFSR to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954.[67]

Independence

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine became an independent state, formalised with a referendum in December 1991. On 21 January 1990, over 300,000 Ukrainians[68] organized a human chain for Ukrainian independence between Kyiv and Lviv. Ukraine officially declared itself an independent country on 24 August 1991, when the communist Supreme Soviet (parliament) of Ukraine proclaimed that Ukraine would no longer follow the laws of USSR and only the laws of the Ukrainian SSR, de facto declaring Ukraine's independence from the Soviet Union. On 1 December, voters approved a referendum formalizing independence from the Soviet Union. Over 90% of Ukrainian citizens voted for independence, with majorities in every region, including 56% in Crimea. The Soviet Union formally ceased to exist on 26 December, when the presidents of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia (the founding members of the USSR) met in Białowieża Forest to formally dissolve the Union in accordance with the Soviet Constitution. With this, Ukraine's independence was formalized de jure and recognized by the international community.

Also on 1 December 1991, Ukrainian voters in their first presidential election elected Leonid Kravchuk.[69] During his presidency, the Ukrainian economy shrank by more than 10% per year (in 1994 by more than 20%).[69] The presidency (1994–2005) of the 2nd President of Ukraine, Leonid Kuchma, was surrounded by numerous corruption scandals and the lessening of media freedoms, including the Cassette Scandal.[69][70] During Kuchma's presidency, the economy recovered, with GDP growth at around 10% a year in his last years in office.[69]

Orange Revolution and Euromaidan

In 2004, Kuchma announced that he would not run for re-election. Two major candidates emerged in the 2004 presidential election. Viktor Yanukovych,[71] the incumbent Prime Minister, supported by both Kuchma and by the Russian Federation, wanted closer ties with Russia. The main opposition candidate, Viktor Yushchenko, called for Ukraine to turn its attention westward and aim to eventually join the EU. In the runoff election, Yanukovych officially won by a narrow margin, but Yushchenko and his supporters alleged that vote rigging and intimidation cost him many votes, especially in eastern Ukraine. A political crisis erupted after the opposition started massive street protests in Kyiv and other cities ("Orange Revolution"), and the Supreme Court of Ukraine ordered the election results null and void. A second runoff found Viktor Yushchenko the winner. Five days later, Yanukovych resigned from office and his cabinet was dismissed on 5 January 2005.

During the Yushchenko term, relations between Russia and Ukraine often appeared strained as Yushchenko looked towards improved relations with the European Union and less toward Russia.[72] In 2005, a highly publicized dispute over natural gas prices with Russia caused shortages in many European countries that were reliant on Ukraine as a transit country.[73] A compromise was reached in January 2006.[73]

By the time of the presidential election of 2010, Yushchenko and Yulia Tymoshenko — allies during the Orange Revolution[74] — had become bitter enemies.[69] Tymoshenko ran for president against both Yushchenko and Viktor Yanukovych, creating a three-way race. Yushchenko, whose popularity had plummeted,[72] persisted in running, and many pro-Orange voters stayed home.[75] In the second round of the election, Yanukovych won the run-off ballot with 48% to Tymoshenko's 45%.[76]

During his presidency (2010–2014), Yanukovych and his Party of Regions were accused of trying to create a "controlled democracy" in Ukraine and of trying to destroy the main opposition party Bloc Yulia Tymoshenko, but both have denied these charges.[77] One frequently cited example of Yanukovych's attempts to centralise power was the 2011 sentencing of Yulia Tymoshenko, which has been condemned by Western governments as potentially being politically motivated.[78]

In November 2013, President Yanukovych did not sign the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement and instead pursued closer ties with Russia.[79][80] This move sparked protests on the streets of Kyiv and, ultimately, the Revolution of Dignity. Protesters set up camps in Kyiv's Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square),[81] and in December 2013 and January 2014 protesters started taking over various government buildings, first in Kyiv, and later in Western Ukraine.[82] Battles between protesters and police resulted in about 80 deaths in February 2014.[83][84]

Following the violence, the Ukrainian parliament on 22 February voted to remove Yanukovych from power (on the grounds that his whereabouts were unknown and he thus could not fulfil his duties), and to free Yulia Tymoshenko from prison. On the same day, Yanukovych supporter Volodymyr Rybak resigned as speaker of the Parliament, and was replaced by Tymoshenko loyalist Oleksandr Turchynov, who was subsequently installed as interim President.[85] Yanukovych had fled Kyiv, and subsequently gave a press conference in the Russian city of Rostov-on-Don.[86]

Western Integration

On 1 January 2016, Ukraine joined the DCFTA with the EU. Ukrainian citizens were granted visa-free travel to the Schengen Area for up to 90 days during any 180-day period on 11 June 2017, and the Association Agreement formally came into effect on 1 September 2017.[87] Significant achievements in the foreign policy arena include support for anti-Russian sanctions, obtaining a visa-free regime with the countries of the European Union, and better recognition of the need to overcome extremely difficult tasks within the country. However, the old local authorities did not want any changes; they were cleansed of anti-Maidan activists (lustration), but only in part. The fight against corruption was launched, but was limited to sentences of petty officials and electronic declarations, and the newly established NABU and NACP were marked by scandals in their work. Judicial reform was combined with the appointment of old, compromised judges. The investigation of crimes against Maidan residents was delayed. In order to counteract the massive global Russian anti-Ukrainian propaganda of the "information war", the Ministry of Information Policy was created, which for 5 years did not show effective work, except for the ban on Kaspersky Lab, Dr.Web, 1С, Mail.ru, Yandex and Russian social networks VKontakte or Odnoklassniki and propaganda media. In 2017, the president signed the law "On Education", which met with opposition from national minorities, and quarreled with the Government of Hungary.

On May 19, 2018, Poroshenko signed a Decree which put into effect the decision of the National Security and Defense Council on the final termination of Ukraine's participation in the statutory bodies of the Commonwealth of Independent States.[88][89] As of February 2019, Ukraine minimized its participation in the Commonwealth of Independent States to a critical minimum and effectively completed its withdrawal. The Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine did not ratify the accession, i.e. Ukraine has never been a member of the CIS.[90]

On January 6, 2019, in Fener, a delegation of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine with the participation of President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko received a Tomos on autocephaly. The Tomos was presented to the head of the OCU, Metropolitan Epiphanius, during a joint liturgy with the Ecumenical Patriarch.[91] The next day, Tomos was brought to Ukraine for a demonstration at St. Sophia Cathedral. On January 9, all members of the Synod of the Constantinople Orthodox Church signed the Tomos during the scheduled meeting of the Synod.

On February 21, 2019, the Constitution of Ukraine was amended, with the norms on the strategic course of Ukraine for membership in the European Union and NATO being enshrined in the preamble of the Basic Law, three articles and transitional provisions.[92]

On 21 April 2019, Volodymyr Zelenskyy was elected president in the second round of the presidential election. Early parliamentary elections on July 21 allowed the newly formed pro-presidential Servant of the People party to win an absolute majority of seats for the first time in the history of independent Ukraine (248). Dmytro Razumkov, the party's chairman, was elected speaker of parliament. The majority was able to form a government on August 29 on its own, without forming coalitions, and approved Oleksii Honcharuk as prime minister.[93] On March 4, 2020, due to a 1.5% drop in GDP (instead of a 4.5% increase at the time of the election), the Verkhovna Rada fired Honcharuk's government and Denys Shmyhal[94] became the new Prime Minister.[95]

On July 28, 2020, in Lublin, Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine created the Lublin Triangle initiative, which aims to create further cooperation between the three historical countries of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and further Ukraine's integration and accession to the EU and NATO.[96]

On May 17, 2021, the Association Trio was formed by signing a joint memorandum between the Foreign Ministers of Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. Association Trio is tripartite format for the enhanced cooperation, coordination, and dialogue between the three countries (that have signed the Association Agreement with the EU) with the European Union on issues of common interest related to European integration, enhancing cooperation within the framework of the Eastern Partnership, and committing to the prospect of joining the European Union.[97]

At the June 2021 Brussels Summit, NATO leaders reiterated the decision taken at the 2008 Bucharest Summit that Ukraine would become a member of the Alliance with the Membership Action Plan (MAP) as an integral part of the process and Ukraine's right to determine its own future and foreign policy without outside interference.[98]

Ukraine was originally preparing to formally apply for EU membership in 2024, but instead signed an application for membership in February 2022.[99]

Russo-Ukrainian War

In March 2014, the Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation occurred. Though official results of a referendum on Crimean reunification with Russia were reported as showing a large majority in favor of the proposition, the vote was organized under Russian military occupation and was denounced by the European Union and the United States as illegal.[100]

The Crimean crisis was followed by pro-Russian unrest in east Ukraine and south Ukraine.[101] In April 2014 Ukrainian separatists self-proclaimed the Donetsk People's Republic and Lugansk People's Republic and held referendums on 11 May 2014; the separatists claimed nearly 90% voted in favor of independence.[102][101] Later in April 2014, fighting between the Ukrainian army and pro-Ukrainian volunteer battalions on one side, and forces supporting the Donetsk and Lugansk People's Republics on the other side, escalated into the war in Donbas.[101][103] By December 2014, more than 6,400 people had died in this conflict, and according to United Nations figures it led to over half a million people becoming internally displaced within Ukraine and two hundred thousand refugees to flee to (mostly) Russia and other neighboring countries.[104][105][106][107] During the same period, political (including adoption of the law on lustration and the law on decommunization) and economic reforms started.[108] On 25 May 2014, Petro Poroshenko was elected president[109] in the first round of the presidential election. By the second half of 2015, independent observers noted that reforms in Ukraine had considerably slowed down, corruption did not subside, and the economy of Ukraine was still in a deep crisis.[108][110][111][112] By December 2015, more than 9,100 people had died (largely civilians) in the war in Donbas,[113] according to United Nations figures.[114]

On February 2, 2021, a presidential decree banned the television broadcasting of the pro-Russian TV channels 112 Ukraine, NewsOne and ZIK.[115][116] The decision of the National Security and Defense Council and the Presidential Decree of February 19, 2021 imposed sanctions on 8 individuals and 19 legal entities, including Putin's pro-Russian politician and Putin's godfather Viktor Medvedchuk and his wife Oksana Marchenko.[117][118]

The Kerch Strait incident occurred on 25 November 2018 when the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) coast guard fired upon and captured three Ukrainian Navy vessels attempting to pass from the Black Sea into the Sea of Azov through the Kerch Strait on their way to the port of Mariupol.[119][120]

Throughout 2021, Russian forces built up along the Russia-Ukraine Border, in occupied Crimea and Donbas, and in Belarus.[121] On February 24, 2022, Russian forces invaded Ukraine.[122] Russia quickly occupied much of the east and south of the country, but failed to advance past the city of Mykolaiv towards Odesa, and were forced to retreat from the north after failing to occupy Kyiv, Chernihiv, Sumy, and Kharkiv.[123] After failing to gain further territories and being driven out of Kharkiv Oblast by a fast-paced Ukrainian counteroffensive,[124] Russia officially annexed the Donetsk People's Republic and the Luhansk People's Republic, along with most of the Kherson and Zaporizhzhia Oblasts on 30 September.[125]

On the eve of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the country was the poorest in Europe,[126] a handicap whose cause was attributed to high corruption levels[127] and the slow pace of economic liberalization and institutional reform.[128][129][130][131] Russia's invasion of the country damaged Ukraine's economy and future prospects of improvement to such an extent, that the GDP of the country was projected to shrink by as much as 35% in its first year alone after the invasion.[132]

National historiography

The scholarly study of Ukraine's history emerged from romantic impulses in the late 19th century when German Romanticism spread to Eastern Europe. The outstanding leaders were Volodymyr Antonovych (1834–1908), based in Kyiv, and his student Mykhailo Hrushevsky (1866–1934).[133] For the first time full-scale scholarly studies based on archival sources, modern research techniques, and modern historical theories became possible. However, the demands of government officials—Tsarist, to a lesser degree Austro-Hungarian and Polish, and later Soviet—made it difficult to disseminate ideas that ran counter to the central government. Therefore, exile schools of historians emerged in central Europe and Canada after 1920.

Strikingly different interpretations of the medieval state of Kyivan Rus appear in the four schools of historiography within Ukraine: Russophile, Sovietophile, Eastern Slavic, and Ukrainophile. In the Soviet Union, there was a radical break after 1921, led by Mikhail Pokrovsky. Until 1934, history was generally not regarded as chauvinistic, but was rewritten in the style of Marxist historiography. National "pasts" were rewritten as social and national liberation for non-Russians, and social liberation for Russians, in a process that ended in 1917. Under Stalin, the state and its official historiography were given a distinct Russian character and a certain Russocentrism. Imperial history was rewritten such that non-Russian love caused an emulation and deference to "join" the Russian people by becoming part of the (tsarist) Russian state, and in return, Russian state interests were driven by altruism and concern for neighboring people.[134] Russophile and Sovietophile schools have become marginalized in independent Ukraine, with the Ukrainophile school being dominant in the early 21st century. The Ukrainophile school promotes an identity that is mutually exclusive of Russia. It has come to dominate the nation's educational system, security forces, and national symbols and monuments, although it has been dismissed as nationalist by Western historians. The East Slavic school, an eclectic compromise between Ukrainophiles and Russophilism, has a weaker ideological and symbolic base, although it is preferred by Ukraine's centrist former elites.[135]

Many historians in recent years have sought alternatives to national histories, and Ukrainian history invited approaches that looked beyond a national paradigm. Multiethnic history recognises the numerous peoples in Ukraine; transnational history portrays Ukraine as a border zone for various empires; and area studies categorises Ukraine as part of East-Central Europe or, less often, as part of Eurasia. Serhii Plokhy argues that looking beyond the country's national history has made possible a richer understanding of Ukraine, its people, and the surrounding regions.[136] since 2015, there has been renewed interest in integrating a "territorial-civic" and "linguistic-ethnic" history of Ukraine. For example, the history of the Crimean Tatars and the more distant history of the Crimea peninsula is now integrated into Ukrainian school history. This is part of the constitutionally mandated "people of Ukraine" rather than "Ukrainian people". Slowly, the histories of Poles and Jews are also slowly being reintegrated. However, due to the current political climate caused by territorial sovereignty breaches by Russia, the role of Russians as "co-host" has been greatly minimized, and there are still unresolved difficult issues of the past, for example, the role of Ukrainians during the Holodomor.[137]

After 1991, historical memory was a powerful tool in the political mobilization and legitimation of the post-Soviet Ukrainian state, as well as the division of selectively used memory along the lines of the political division of Ukrainian society. Ukraine did not experience the restorationist paradigm typical of some other post-Soviet nations, for example the three Baltic countries —Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, although the multifaceted history of independence, the Orthodox Church in Ukraine, Soviet-era repressions, mass famine, and World War II collaboration were used to provide a different constitutive frame for developing Ukrainian nationhood. The politics of identity (which includes the production of history textbooks and the authorization of commemorative practices) has remained fragmented and tailored to reflect the ideological anxieties and concerns of individual regions of Ukraine.[138]

Canadian historiography on Ukraine

In Soviet Ukraine, twentieth-century historians were strictly limited in the range of models and topics they could cover, with Moscow insisting on an official Marxist approach. However, émigré Ukrainians in Canada developed an independent scholarship that ignored Marxism, and shared the Western tendencies in historiography.[139] George W. Simpson and Orest Subtelny were leaders promoting Ukrainian studies in Canadian academe.[140] The lack of independence in Ukraine meant that traditional historiographical emphases on diplomacy and politics were handicapped. The flourishing of social history after 1960 opened many new approaches for researchers in Canada; Subtelny used the modernization model. Later historiographical trends were quickly adapted to the Ukrainian evidence, with special focus on Ukrainian nationalism. The new cultural history, post-colonial studies, and the "linguistic turn" augmenting, if not replacing social history, allowed for multiple angles of approach. By 1991, historians in Canada had freely explored a wide range of approaches regarding the emergence of a national identity. After independence, a high priority in Canada was assisting in the freeing of Ukrainian scholarship from Soviet-Marxist orthodoxy—which downplayed Ukrainian nationalism and insisted that true Ukrainians were always trying to reunite with Russia. Independence from Moscow meant freedom from an orthodoxy that was never well suited to Ukrainian developments. Scholars in Ukraine welcomed the "national paradigm" that Canadian historians had helped develop. Since 1991, the study of Ukrainian nation-building became an increasingly global and collaborative enterprise, with scholars from Ukraine studying and working in Canada, and with conferences on related topics attracting scholars from around the world.[141]

See also

Notes

- 'Regardless of the uncertainties surrounding the origin of Rus', with Helgi/Oleh (reigned 878–912) we have a known historical figure credited with building the foundations of a Kievan state. (...) With Oleh's invasion of Kiev and the assassination of Askol'd and Dir in 882, the consolidation of the East Slavic and Finnic tribes under the authority of the Varangian Rus' had begun.'[33]

References

- Matossian Shaping World History p. 43

- "What We Theorize – When and Where Did Domestication Occur". International Museum of the Horse. Retrieved 12 December 2010.(Citation does not exist anymore)

- "Horsey-aeology, Binary Black Holes, Tracking Red Tides, Fish Re-evolution, Walk Like a Man, Fact or Fiction". Quirks and Quarks Podcast with Bob Macdonald. CBC Radio. 7 March 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2010.(Link does not exist anymore)

- Kroll, Piotr (2008). Od ugody hadziackiej do Cudnowa. Kozaczyzna między Rzecząpospolitą a Moskwą w latach 1658-1660. doi:10.31338/uw.9788323518808. ISBN 9788323518808.

- Riasanovsky, Nicholas V. (1963). A History of Russia. Oxford University Press. p. 199.

- Jerzy Jan Lerski; Piotr Wróbel; Richard J. Kozicki (1996). Historical dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0.

- Norman Davies (1982). God's Playground, a History of Poland: The origins to 1795. Columbia University Press. p. 406. ISBN 978-0-231-05351-8.

- Eugeniusz Romer, O wschodniej granicy Polski z przed 1772 r., w: Księga Pamiątkowa ku czci Oswalda Balzera, t. II, Lwów 1925, s. [355].

- Jacek Staszewski, August II Mocny, Wrocław 1998, p. 100.

- Riasanovsky (1963), p. 537.

- "Ukraine – The famine of 1932–33". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- "Macroeconomic Indicators". National Bank of Ukraine. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007.

- Inozmi, "Ukraine – macroeconomic economic situation" Archived 22 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine. June 2009.

- Gray, Richard (18 December 2011). "Neanderthals built homes with mammoth bones". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 21 December 2011.

- "Molodova I and V (Ukraine)". Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- Prat, Sandrine; Péan, Stéphane C.; Crépin, Laurent; Drucker, Dorothée G.; Puaud, Simon J.; Valladas, Hélène; Lázničková-Galetová, Martina; van der Plicht, Johannes; et al. (17 June 2011). "The Oldest Anatomically Modern Humans from Far Southeast Europe: Direct Dating, Culture and Behavior". PLOS ONE. plosone. 6 (6): e20834. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620834P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020834. PMC 3117838. PMID 21698105.

- Carpenter, Jennifer (20 June 2011). "Early human fossils unearthed in Ukraine". BBC. Retrieved 21 June 2011.

- "Trypillian Civilization 5,508 – 2,750 BC". The Trypillia-USA-Project. Archived from the original on 12 December 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- "Scythian". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- Joseph Roisman,Ian Worthington. "A companion to Ancient Macedonia" John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 978-1-4443-5163-7 pp 135–138, pp 343–345

- The Oxford Classical Dictionary by Simon Hornblower and Antony Spawforth,ISBN 0-19-860641-9,"page 1515,"The Thracians were subdued by the Persians by 516"

- Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (1959). A history of Greece to 322 B.C. Clarendon Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-19-814260-7. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- Mitchiner, Michael (1978). The Ancient & Classical World, 600 B.C.-A.D. 650. Hawkins Publications. p. 69. ISBN 978-0-904173-16-1.

- Bunson, Matthew (1995). A dictionary of the Roman Empire. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 116. ISBN 0195102339.

- "Ancient period - History - About Chersonesos, Sevastopol". www.chersonesos.org. Archived from the original on 12 August 2004.

- Migliorati, Guido (2003). Cassio Dione e l'impero romano da Nerva ad Anotonino Pio: alla luce dei nuovi documenti (in Italian). Vita e Pensiero. p. 6. ISBN 88-343-1065-9.

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). A History of Ukraine. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 27. ISBN 0-8020-0830-5.

- Frolova, N. (1999). "The Question of Continuity in the Late Classical Bosporus On the Basis of Numismatic Data". Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia. 5 (3): 179–205. doi:10.1163/157005799X00188. ISSN 0929-077X.

- Lawler, Jennifer (2015). Encyclopedia of the Byzantine Empire. McFarland. p. 137. ISBN 978-1-4766-0929-4.

- Gautier, Paul. "Le dossier d’un haut fonctionnaire byzantin d’Alexis Ier Comnène, Manuel Stra-boromanos". Revue des études byzantines, Paris, Vol.23, 1965. pp. 178, 190

- Barford, P. M. (2001). The early Slavs : culture and society in early medieval Eastern Europe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 32. ISBN 0-8014-3977-9. OCLC 47054689.

- М. Грушевський – "Історія України". Том І, розділ IV, Велике слов'янське розселення: Історія Антів, їх походи, війна з Словянами, боротьба з Аварами, останні звістки, про Антів

- Magocsi 2010, p. 65–66.

- Tolochko P. P., Ivakin G. Y., Vermenych Y.V. Kyiv. in Encyclopedia of Ukrainian History (Енциклопедія історії України). — Kyiv: Naukova Dumka, 2007. — vol. 4. — P. 201-218.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 30.

- Magocsi 2010, p. 59.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 31–32, 47.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 30–32, 47, 57.

- "Kiëv; Rusland §2. Het Rijk van Kiëv". Encarta Encyclopedie Winkler Prins (in Dutch). Microsoft Corporation/Het Spectrum. 2002.

- Plokhy 2006, p. 13.

- Khvalkov, Evgeny (2017). The colonies of Genoa in the Black Sea region : evolution and transformation. New York, NY. p. 69. ISBN 978-1-351-62306-3. OCLC 994262849.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Magocsi 2010, p. 123.

- "Генуэзские колонии в Одесской области - Бизнес-портал Измаила". 5 February 2018. Archived from the original on 5 February 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- "О СОПЕРНИЧЕСТВЕ ВЕНЕЦИИ С ГЕНУЕЮ В XIV-м ВЕКЕ". www.vostlit.info. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- "Эпиграфические памятники Каффы | Старый музей" (in Russian). 26 March 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- Voloshchuk, Myroslav. Chwalba, Andrzej; Zamorski, Krzysztof (eds.). The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth: History, Memory, Legacy.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - "History". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com.

- Millar, Robert (21 July 2010). Authority and Identity: A Sociolinguistic History of Europe before the Modern Age. Springer. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-230-28203-2.

- "Mukha rebellion". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com.

- Brian Glyn Williams (2013). "The Sultan's Raiders: The Military Role of the Crimean Tatars in the Ottoman Empire" (PDF). The Jamestown Foundation. p. 27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 October 2013.

- Darjusz Kołodziejczyk, as reported by Mikhail Kizilov (2007). "Slaves, Money Lenders, and Prisoner Guards:The Jews and the Trade in Slaves and Captivesin the Crimean Khanate". The Journal of Jewish Studies. 58 (2): 189–210. doi:10.18647/2730/JJS-2007.

- Yakovenko, N. Ukrainian nobility from the end of 14th century to the mid of 17th century. Ed.2. Krytyka. Kyiv 2008. ISBN 966-8978-14-5.

- A. Jabłonowski, Źródła Dziejowe (Warsaw, 1889) xix: 73

- Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation by Serhy Yekelchyk, Oxford University Press (2007), ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3

- "Документи про заборону української мови". 19 August 2016. Archived from the original on 19 August 2016. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- Orest Subtelny; Ukraine: A History; University of Toronto Press; 2000. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0. pp 117-145-146-148

- "History of Ukraine". www.encyclopediaofukraine.com. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- Paul Kubicek, The History of Ukraine (2008) p 79

- Orest Subtelny (2000). Ukraine: A History. U of Toronto Press. p. 359. ISBN 9780802083906.

- "The famine of 1932–33" Archived 5 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica. Quote: "The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33 – a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians... Its deliberate nature is underscored by the fact that no physical basis for famine existed in Ukraine... Soviet authorities set requisition quotas for Ukraine at an impossibly high level. Brigades of special agents were dispatched to Ukraine to assist in procurement, and homes were routinely searched and foodstuffs confiscated... The rural population was left with insufficient food to feed itself."

- Anne Applebaum. Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine (2017) Archived 27 February 2022 at the Wayback Machine.

- Rosenfeld, Alvin H., ed. (2013). Resurgent Antisemitism. Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253008909.

- Pietrzak, Michał (2018). "Wprowadzenie". In Borecki, Paweł (ed.). O ustroju, prawie i polityce II Rzeczypospolitej. Pisma wybrane (in Polish). Wolters Kluwer. p. 9.

- "Opinion | The messy, bloody history that led Ukraine into the impeachment inquiry". NBC News. 28 September 2019.

- "Mariusz Zajączkowski: 1943 Volhynia massacre". Archived from the original on 13 April 2014. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- "Ukrainian Insurgent Army: Myths and facts - Oct. 12, 2012". KyivPost. 12 October 2012.

- Crimea profile – Overview, BBC News

- Subtelny, Orest (2000). Ukraine: A History. University of Toronto Press. p. 576. ISBN 0-8020-8390-0.

- Ukraine country profile – Overview Archived 25 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News

- Adrian Karatnycky, "Ukraine's Orange Revolution," Foreign Affairs, Vol. 84, No. 2 (Mar. – Apr. 2005), pp. 35–52 in JSTOR Archived 6 December 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- "Yanukovych is president". UaWarExplained.com. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Profile: Viktor Yushchenko Archived 23 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News

- Ukraine country profile – Overview 2012 Archived 9 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News

- "The Orange Revolution". UaWarExplained.com. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Ukraine's New President: Is the Orange Revolution Over?, Time.com (11 February 2010)

- "The Orange Revolution". UaWarExplained.com. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Ukraine right-wing politics: is the genie out of the bottle? Archived 14 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, openDemocracy.net (3 January 2011)

Ukraine viewpoint: Novelist Andrey Kurkov Archived 11 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (13 January 2011)

Ukraine ex-PM Tymoshenko charged with misusing funds Archived 1 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (20 December 2010)

The Party of Regions monopolises power in Ukraine Archived 3 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Centre for Eastern Studies (29 September 2010)

Ukraine launches battle against corruption Archived 21 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (18 January 2011)

Ukrainians' long wait for prosperity Archived 21 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (18 October 2010)

Ukraine:Journalists Face Uncertain Future Archived 5 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting (27 October 2010)

"Our Ukraine comes to defense of Tymoshenko, Lutsenko, Didenko, Makarenko in statement". Interfax-Ukraine. 25 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 June 2012. - "U.S. Government Statement of Concern about Arrest of Former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 8 February 2016. US Embassy, Kyiv, (24 September 2011)

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-14459446 Archived 21 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine BBC News, (24 September 2011) - Why is Ukraine in turmoil? Archived 18 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (21 February 2014)

- "Ukraine 'still wants to sign EU deal' | News | al Jazeera".

- Ukraine crisis: Police storm main Kyiv 'Maidan' protest camp Archived 1 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (19 February 2014)

- Ukraine protests timeline Archived 3 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (21 February 2014)

- Sandford Daniel (19 February 2014). "Ukraine crisis: Renewed Kyiv assault on protesters". BBC News. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- "Ukraine crisis: Yanukovych announces 'peace deal'". BBC News. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Profile: Olexander Turchynov". BBC News. 23 February 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- Taylor, Charles (28 February 2014). "Profile: Ukraine's ousted President Viktor Yanukovych". BBC News. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- "European Commission - EU-Ukraine Association Agreement fully enters into force". europa.eu. (Press release)

- "Україна остаточно вийшла з СНД". espreso.tv. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- "Президент підписав Указ про остаточне припинення участі України у статутних органах СНД — Офіційне інтернет-представництво Президента України". Офіційне інтернет-представництво Президента України (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- Лащенко, Олександр (26 November 2020). "Україні не потрібно виходити із СНД – вона ніколи не була і не є зараз членом цієї структури". Радіо Свобода.

- "Οικουμενικό Πατριαρχείο" (in Greek). Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- "The law amending the Constitution on the course of accession to the EU and NATO has entered into force | European integration portal". eu-ua.org (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- Kitsoft. "Кабінет Міністрів України — Новим Прем'єр-міністром України став Олексій Гончарук". www.kmu.gov.ua (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Гончарука звільнили з посади прем'єра й відставили весь уряд". BBC News Україна (in Ukrainian). 4 March 2020. Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Денис Шмигаль – новий прем'єр України". Українська правда (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 6 July 2020.

- "Lithuania, Poland and Ukraine Inaugurate 'Lublin Triangle'". Jamestown.

- "Україна, Грузія та Молдова створили новий формат співпраці для спільного руху в ЄС". www.eurointegration.com.ua.

- "Brussels Summit Communiqué issued by the Heads of State and Government participating in the meeting of the North Atlantic Council in Brussels 14 June 2021". NATO.

- "У 2024 році Україна подасть заявку на вступ до ЄС". www.ukrinform.ua. 29 January 2019.

- "Crimea referendum: Voters 'back Russia union'". BBC News. 10 March 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2014.

- Ukraine crisis timeline Archived 3 June 2014 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News

- Putin Tells Separatists In Ukraine To Postpone May 11 Referendum Archived 19 March 2015 at the Wayback Machine, NPR (7 May 2014)

"Ukraine rebels hold referendums in Donetsk and Luhansk". BBC News. 11 May 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

"Russian Roulette (Dispatch Thirty-Eight)". Vice News. 13 May 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2014. - Ukraine underplays role of far right in conflict Archived 2 June 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (13 December 2014)

- Fergal Keane reports from Mariupol on Ukraine's 'frozen conflict' Archived 23 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (12 December 2014)

- Half a million displaced in eastern Ukraine as winter looms, warns UN refugee agency Archived 11 November 2016 at the Wayback Machine, United Nations (5 December 2014)

- Ukraine conflict: Refugee numbers soar as war rages Archived 8 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine, BBC News (5 August 2014)

- UN Says At Least 6,400 Killed In Ukraine's Conflict Since April 2014 Archived 23 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, RFE/RL (1 June 2015)

- "Ukraine Reform Monitor: August 2015". Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. August 2015. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- "Petro Poroshenko becomes President of Ukraine". UaWarExplained.com. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Bershidsky, Leonid (6 November 2015). "Ukraine Is in Danger of Becoming a Failed State". Bloomberg News. Archived from the original on 10 November 2015. Retrieved 8 November 2015.

- Kuzio, Taras (25 August 2015). "Money Still Rules Ukraine". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- Minakov, Mikhail; Stavniichuk, Maryna (16 February 2016). "Ukraine's constitution: reform or crisis?". OpenDemocracy. Archived from the original on 17 February 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Separate districts of Donbas and Luhansk regions (ORDLO)". UaWarExplained.com. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- At Least 9,115 Killed in Ukraine Conflict, U.N. Says Archived 24 July 2016 at the Wayback Machine, New York Times (9 December 2015)

Kyiv, Separatists Accuse Each Other Of Violating Holiday Cease-Fire Archived 26 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Radio Free Europe (24 December 2015) - "УКАЗ ПРЕЗИДЕНТА УКРАЇНИ №43/2021". Офіційне інтернет-представництво Президента України (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "Зеленський "вимкнув" 112, ZIK і NewsOne з ефіру. Що відомо". BBC News Україна (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- "УКАЗ ПРЕЗИДЕНТА УКРАЇНИ №64/2021". Офіційне інтернет-представництво Президента України (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "Зеленський ввів у дію санкції проти Медведчука". Українська правда (in Ukrainian). Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "Tension escalates after Russia seizes Ukraine naval ships". BBC News. 26 November 2018. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- Polityuk, Andrew Osborn, Pavel (26 November 2018). "Russia fires on and seizes Ukrainian ships near annexed Crimea". Reuters. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Buildup of Russian forces along Ukraine's border that has some talking of war". NPR.org. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- Ellyatt, Holly (24 February 2022). "Russian forces invade Ukraine". CNBC. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- Bigg, Matthew Mpoke (13 September 2022). "Russia invaded Ukraine more than 200 days ago. Here is one key development from every month of the war". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- Ortiz, John Bacon and Jorge L. "Russians admit defeat in Kharkiv; Zelenskyy visits Izium after troops flee shattered city: Ukraine updates". USA TODAY. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- Maynes, Charles (30 September 2022). "Putin illegally annexes territories in Ukraine, in spite of global opposition". NPR. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- "GDP per capita (Current US$) | Data".

- Bullough, Oliver (6 February 2015). "Welcome to Ukraine, the most corrupt nation in Europe". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

Since 1991, officials, members of parliament and businessmen have created complex and highly lucrative schemes to plunder the state budget. The theft has crippled Ukraine. The economy was as large as Poland's at independence, now it is a third of the size. Ordinary Ukrainians have seen their living standards stagnate, while a handful of oligarchs have become billionaires.

- "Ukraine: Can meaningful reform come out of conflict?". Bruegel | The Brussels-based economic think tank. 25 July 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Pikulicka-Wilczewska, Agnieszka (19 July 2017). "Why the reforms in Ukraine are so slow?". New Eastern Europe - A bimonthly news magazine dedicated to Central and Eastern European affairs. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- "The slow-reform trap". Bruegel | The Brussels-based economic think tank. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- "Ukraine Country Assistance Evaluation" (PDF). www.oecd.org. 8 November 2000.

- Gramer, Amy Mackinnon, Robbie (5 October 2022). "The Battle to Save Ukraine's Economy From the War". Foreign Policy. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Serhii Plokhy, Unmaking Imperial Russia: Mykhailo Hrushevsky and the Writing of Ukrainian History (2005)

- Velychenko, Stephen (1993). Shaping Identity in Eastern Europe and Russia : Soviet-Russian and Polish Accounts of Ukrainian History, 1914?1991. New York. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-137-05825-6. OCLC 1004379833.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Taras Kuzio, "National Identity and History Writing in Ukraine," Nationalities Papers 2006 34(4): 407–427, online in EBSCO

- Serhii Plokhy, "Beyond Nationality" Ab Imperio 2007 (4): 25–46,

- The politics of memory in Poland and Ukraine : from reconciliation to de-conciliation. Tomasz Stryjek, Joanna Konieczna-Sałamatin. London. 2022. p. 98. ISBN 978-1-003-01734-9. OCLC 1257314140.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - See Andriy Portnov, "Exercises with history Ukrainian style (notes on public aspects of history's functioning in post-Soviet Ukraine)," Ab Imperio 2007 (3): 93–138, in Ukrainian

- Roman Senkus, "Ukrainian Studies in Canada Since the 1950s: An Introduction." East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 5.1 (2018): 3–7.

- Bohdan Krawchenko, "Ukrainian studies in Canada." Nationalities Papers 6#1 (1978): 26–43.

- Serhy Yekelchyk, "Studying the Blueprint for a Nation: Canadian Historiography of Modern Ukraine," East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies (2018) 5#1 pp 115–137. online Archived 28 February 2019 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

Surveys and reference

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine (University of Toronto Press, 1984–93) 5 vol; from Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, partly online as the Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine.

- Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopedia. ed by Volodymyr Kubijovyč; University of Toronto Press. 1963; 1188pp

- Allen, W. E. D. (1963). The Ukraine: a history. Russell & Russell. p. 404. OCLC 578666051.

- Bilinsky, Yaroslav The Second Soviet Republic: The Ukraine after World War II (Rutgers UP, 1964)

- Doroshenko, Dmytro, History of the Ukraine. Institute Press (Edmonton, Alberta), 1939: Online.

- Hrushevsky, Mykhailo. A History of Ukraine (1986 [1941]).

- Hrushevsky, Mykhailo. History of Ukraine-Rus' in 9 volumes (1866–1934). Available online in Ukrainian as "Історія України-Руси" (1954–57). Translated into English (1997–2014).

- Ivan Katchanovski; Kohut, Zenon E.; Nebesio, Bohdan Y.; and Yurkevich, Myroslav. Historical Dictionary of Ukraine. Second edition (2013). 968 pp.

- Kubicek, Paul. The History of Ukraine (2008) excerpt and text search

- Liber, George. Total wars and the making of modern Ukraine, 1914–1954 (U of Toronto Press, 2016).

- Magocsi, Paul R. (2010) [1996]. A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples (2nd rev. ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 9781442610217.

- Manning, Clarence, The Story of the Ukraine. Georgetown University Press, 1947: Online.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2006). The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139458924.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2015). The Gates of Europe: A History of Ukraine. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465050918.

- Reid, Anna. Borderland: A Journey Through the History of Ukraine (2003) ISBN 0-7538-0160-4

- Snyder, Timothy D. (2003). The Reconstruction of Nations: Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania, Belarus, 1569–1999. Yale U.P. ISBN 9780300105865. pp. 105–216.

- Subtelny, Orest (2009). Ukraine: A History. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8390-6. A Ukrainian translation is available online.

- Wilson, Andrew. The Ukrainians: Unexpected Nation. Yale University Press; 2nd edition (2002) ISBN 0-300-09309-8.

- Yekelchyk, Serhy (2007). Ukraine: Birth of a Modern Nation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530546-3. OCLC 219616283.

Topical studies

- Kononenko, Konstantyn. Ukraine and Russia: A History of the Economic Relations between Ukraine and Russia, 1654–1917 (Marquette University Press 1958)

- Luckyj, George S. Towards an Intellectual History of Ukraine: An Anthology of Ukrainian Thought from 1710 to 1995. (1996)

- Shkandrij, Myroslav. Ukrainian Nationalism: Politics, Ideology, and Literature, 1929–1956 (Yale University Press; 2014) 331 pages; Studies the ideology and legacy of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists Especially by Dmytro Dontsov, Olena Teliha, Leonid Mosendz, Oleh Olzhych, Yurii Lypa, Ulas Samchuk, Yurii Klen, and Dokia Humenna.

1930s, World War II

- Applebaum, Anne. Red Famine: Stalin's War on Ukraine (2017); 496 pp online review

- Boshyk, Yuri (1986). Ukraine During World War II: History and Its Aftermath. Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. ISBN 0-920862-37-3.

- Berkhoff, Karel C., Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine Under Nazi Rule. Harvard U. Press, 2004. 448 pp.

- Brandon, Ray, and Wendy Lower, eds. The Shoah in Ukraine: History, Testimony, Memorialization. (2008). 378 pp. online review

- Conquest, Robert. The Harvest Of Sorrow: Soviet Collectivisation and the Terror-Famine (1986)