Proconsul (mammal)

Proconsul is an extinct genus of primates that existed from 21 to 17 million years ago during the Miocene epoch. Fossil remains are present in Eastern Africa including Kenya and Uganda. Four species have been classified to date: P. africanus, P. gitongai, P. major and P. meswae. The four species differ mainly in body size. Environmental reconstructions for the Early Miocene Proconsul sites are still tentative and range from forested environments to more open, arid grasslands.

| Proconsul Temporal range: Miocene, | |

|---|---|

.JPG.webp) | |

| Proconsul skeleton reconstruction | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | †Proconsulidae |

| Subfamily: | †Proconsulinae |

| Genus: | †Proconsul Hopwood, 1933 |

| Species | |

| |

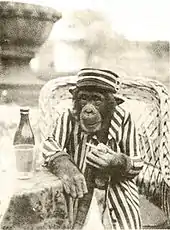

The gibbon and great apes, including humans, are held in evolutionary biology to share a common ancestral lineage, which may have included Proconsul. Its name, meaning "before Consul" (Consul being a certain chimpanzee that, at the time of the genus's discovery, was on display in London), implies that it is ancestral to the chimpanzee. It might also be ancestral to the rest of the apes.

Description

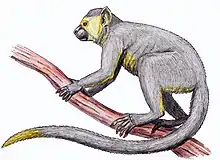

The genus had a mixture of Old World monkey and ape characteristics, so its placement in the ape superfamily Hominoidea is tentative, with some scientists placing Proconsul outside it, before the split of the apes and Old World monkeys.

Proconsul's monkey-like features include pronograde posture, indicated by a long flexible back, curved metacarpals, and an above-branch arboreal quadrupedal positional repertoire. The primary feature linking Proconsul with extant apes is its lack of a tail; other "ape-like" features include its enhanced grasping capabilities, stabilized elbow joint and facial structure. Proconsul could not hang effortlessly from tree branches like gibbons and other nonhuman apes do today.

Discovery and classification

The first specimen, a partial jaw discovered in 1909 by a gold prospector at Koru, near Kisumu in western Kenya, was also the oldest fossil hominoid known until recently, and the first fossil mammal ever found in sub-Saharan Africa. The name, Proconsul, was devised by Arthur Hopwood in 1933 and means "before Consul" – the name of a famous captive chimpanzee in London.[1] At the time Consul was being used as a circus name for performing chimpanzees. The Folies Bergère of 1903 in Paris had a popular performing chimpanzee named Consul, and so did the Belle Vue Zoological Gardens in Manchester, England, in 1894. On the latter's death in that year Ben Brierley wrote a commemorative poem wondering where the "Missing Link" between chimpanzees and men was.[2]

Hopwood in 1931 had discovered the fossils of three individuals while expeditioning with Louis Leakey in the vicinity of Lake Victoria. The Consul that he selected to use in the name was neither of the ones mentioned above, but another located in the London Zoo. Consul is being used Linnaean-style to symbolize the chimpanzee. Proconsul is therefore "ancestral to the Chimpanzee" in Hopwood's words. He also added africanus as the specific name.[1]

Other fossils discovered later were initially classified as africanus and subsequently reclassified; that is, the total pool of fossils originally considered africanus was split and the fragments lumped with other finds to create a new species. For example, Mary Leakey's famous find of 1948 began as africanus and was split from it to be lumped with Thomas Whitworth's finds of 1951 as heseloni by Alan Walker in 1993. This process creates some confusion for the public, which is told that africanus became heseloni. The finds from Koru and Songhor are still considered africanus. Four species are still defined even though many fossils have jumped species.[3]

The family of Proconsulidae was first proposed by Louis Leakey in 1963,[4] a decade after he and Wilfrid Le Gros Clark had defined africanus, nyanzae and major. It was not immediately accepted but ultimately prevailed.

The history of hominoid classification in the second half of the 20th century is sufficiently complex to warrant a few books itself. Most of the palaeoanthropologists have changed their minds at least once as new fossils have come to light and new observations have been made, and will probably continue to do so. The classifications found in the literature of one decade are not generally the same as those of another.[5] For example, in 1987 Peter Andrews and Lawrence Martin, established palaeontologists, took the point of view that Proconsul is not a hominoid, but is a sister taxon to it.[6]

Notes

- Morell 1996, p. 130

- Walker & Shipman 2005

- Tuttle 2006, Taxonomic Shuffles, Ancestors, and Functional Interpretations: 1960–1999, p. 17

- "Proconsulidae". Palaeodatabase.

- A recapitulation of the changing classifications of fossils at some time regarded as Proconsul can be found in Tuttle 2006

- Andrews & Martin 1987. They also believed at that time that humans and African apes formed distinct clades.

- McNulty, Kieran P.; Begun, David R.; Kelley, Jay; Manthi, Fredrick K.; Mbua, Emma N. (2015). "A systematic revision of Proconsul with the description of a new genus of early Miocene hominoid". Journal of Human Evolution. 84: 42–61. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.03.009. PMID 25962549.

References

- Andrews, Peter; Martin, Lawrence (January 1987). "Cladistic relationships of extant and fossil hominoids". Journal of Human Evolution. 16 (1): 101–118. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(87)90062-5.

- Morell, Virginia (1996). Ancestral Passions: The Leakey Family and the Quest for Humankind's Beginnings. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684824703.

- Tuttle, Russel H. (2006). "Seven Decades of East African Miocene Anthropoid Studies" (PDF). In Ishida, Hidemi; Tuttle, Russell; Pickford, Martin; Ogihara, Naomichi; Nakatsukasa, Masato (eds.). Human Origins and Environmental Backgrounds. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-29638-8.

- Walker, Alan; Shipman, Pat (2005). The Ape in the Tree: An Intellectual & Natural History of Proconsul. Cambridge, Massachusetts, London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01675-0.