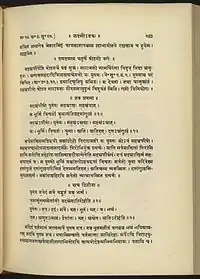

Purusha Sukta

Purusha suktam (Sanskrit पुरुषसूक्तम्) is an interpolated hymn added to 10.90 of the Rigveda at a later period.[1] It is dedicated to the Purusha, the "Cosmic Being".[2]

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

It is also found in the Shukla Yajurveda Samhita 31.1–16 and Atharva Veda Samhita 19.6.[3][4]

Slightly different versions of the Sukta appear in different Vedas,[5] one version of the suktam has 16 verses, 15 in the anuṣṭubh meter, and the final one in the triṣṭubh meter. Another version of the Sukta consists of 24 verses with the first 18 mantras designated as the Purva-narayana and the later portion termed as the Uttara-narayana probably in honour of Rishi Narayana.

Scholars state that verses of Purusha Sukta are later interpolations to the Rigveda.[1] One of the reasons given is that it is the only hymn in all the Vedas that mentions the four varnas by name – although the word "varṇa" itself is not mentioned in the hymn.[1][6][7]

Contents

The Purusha Sukta gives a description of the spiritual unity of the universe. It presents the nature of Purusha, or the cosmic being, as both immanent in the manifested world and yet transcendent to it.[8] From this being, the Sukta holds, the original creative will (identified with Viswakarma, Hiranyagarbha or Prajapati) proceeds which causes the projection of the universe in space and time.[9] The Purusha Sukta, in the seventh verse, hints at the organic connectedness of the various classes of society.

Purusha

The Purusha is defined in verses 2 to 5 of the Sukta. He is described as a being who pervades everything conscious and unconscious universally. He is poetically depicted as a being with thousand heads, eyes and legs, enveloping not just the earth, but the entire universe from all sides and transcending it by ten fingers length – or transcending in all 10 dimensions. All manifestations, in past, present and future, is held to be the Purusha alone.[10] It is also proclaimed that he transcends his creation. The immanence of the Purusha in manifestation and yet his transcendence of it is similar to the viewpoint held by panentheists. Finally, his glory is held to be even greater than the portrayal in this Sukta.

Creation

Verses 5–15 hold the creation of the Rig Veda. Creation is described to have started with the origination of Virat, or the astral body from the Purusha. In Virat, omnipresent intelligence manifests itself which causes the appearance of diversity. In the verses following, it is held that Purusha through a sacrifice of himself, brings forth the avian, forest-dwelling, and domestic animals, the three Vedas, the meters (of the mantras). Then follows a verse that states that from his mouth, arms, thighs, and feet the four varnas (categories) are born.

After the verse, the Sukta states that the moon takes birth from the Purusha's mind and the sun from his eyes. Indra and Agni descend from his mouth and from his vital breath, air is born. The firmament comes from his navel, the heavens from his head, the earth from his feet and quarters of space from his ears.[8] Through this creation, underlying unity of human, cosmic and divine realities is espoused, for all are seen arising out of same original reality, the Purusha.[11]

Yajna

The Purusha Sukta holds that the world is created by and out of a Yajna or exchange of the Purusha. All forms of existence are held to be grounded in this primordial yajna. In the seventeenth verse, the concept of Yajna itself is held to have arisen out of this original sacrifice. In the final verses, yajna is extolled as the primordial energy ground for all existence.[12]

Context

The Sukta gives an expression to immanence of radical unity in diversity and is therefore, seen as the foundation of the Vaishnava thought, Bhedabheda school of philosophy and Bhagavata theology.[13]

The concept of the Purusha is from the Samkhya Philosophy which is traced to the Indus Valley period (OVOP). It seems to be an interpolation into the Rigveda since it is out of character with the other hymns dedicated to nature gods.[14]

The Purusha Sukta is repeated with some variations in the Atharva Veda (19.6). Sections of it also occur in the Panchavimsha Brahmana, Vajasaneyi Samhita and the Taittiriya Aranyaka.[15] Among Puranic texts, the Sukta has been elaborated in the Bhagavata Purana (2.5.35 to 2.6.1–29) and in the Mahabharata (Mokshadharma Parva 351 and 352).

The Purusha Sukta is mirrored directly in the ancient Zoroastrian texts, found in the Avesta Yasna and the Pahlavi Denkard. There, it is said that the body of man is in the likeness of the four estates, with priesthood at the head, warriorship in the hands, husbandry in the belly, and artisanship at the foot.

Authenticity

Many 19th and early 20th century scholars questioned as to when parts or all of Purusha Sukta were composed, and whether some of these verses were present in the ancient version of Rigveda. They suggest it was interpolated in post-Vedic era[16] and is a relatively modern origin of Purusha Sukta.[1][6]

As compared with by far the largest part of the hymns of the Rigveda, the Purusha Sukta has every character of modernness both in its diction and ideas. I have already observed that the hymns which we find in this collection (Purusha Sukta) are of very different periods.

That the Purusha Sukta, considered as a hymn of the Rigveda, is among the latest portions of that collection, is clearly perceptible from its contents.

That remarkable hymn (the Purusha Sukta) is in language, metre, and style, very different from the rest of the prayers with which it is associated. It has a decidedly more modern tone, and must have been composed after the Sanskrit language had been refined.

There can be little doubt, for instance, that the 90th hymn of the 10th book (Purusha Sukta) is modern both in its character and in its diction. (...) It mentions the three seasons in the order of the Vasanta, spring; Grishma, summer; and Sarad, autumn; it contains the only passage in the Rigveda where the four castes are enumerated. The evidence of language for the modern date of this composition is equally strong. Grishma, for instance, the name for the hot season, does not occur in any other hymn of the Rigveda; and Vasanta also does not belong to the earliest vocabulary of the Vedic poets.

B. V. Kamesvara Aiyar, another 19th-century scholar, on the other hand, disputed this idea:[10]

The language of this hymn is particularly sweet, rhythmical and polished and this has led to its being regarded as the product of a later age when the capabilities of the language had been developed. But the polish may be due to the artistic skill of the particular author, to the nature of the subject and to several other causes than mere posteriority in time. We might as well say that Chaucer must have lived centuries after Gower, because the language of the former is so refined and that of the latter, so rugged. We must at the same time confess that we are unable to discover any distinct linguistic peculiarity in the hymn which will stamp it as of a later origin.

Scholarship on this and other Vedic topics has moved on decisively since the end of the twentieth century, especially since the major publications of Brereton & Jamison and many others, and views such as the above are nowadays of interest only as part of the history of indology, and not as contributions to contemporary scholarship.

Modern scholarship

The verses about social estates in the Purusha Sukta are considered to belong to the latest layer of the Rigveda by scholars such as V. Nagarajan, Jamison and Brereton. V. Nagarajan believes that it was an "interpolation" to give "divine sanction" to an unequal division in society that was in existence at the time of its composition. He states "The Vedic Hymns had been composed before the Varna scheme was implemented. The Vedic society was not organized on the basis of varnas. The Purusha Sukta might have been a later interpolation to secure Vedic sanction for that scheme".[1] Stephanie Jamison and Joel Brereton, a professor of Sanskrit and Religious studies, state, "there is no evidence in the Rigveda for an elaborate, much-subdivided and overarching caste system", and "the varna system seems to be embryonic in the Rigveda and, both then and later, a social ideal rather than a social reality".[21]

See also

- Śrī Sūkta

- Historical Vedic religion

- List of suktas and stutis

- Nasadiya Sukta (Hymn of Creation)

- Agganna Sutta — a Buddhist critique

- Varna (Hinduism) and Caste system in India

Notes

- David Keane (2016). Caste-based Discrimination in International Human Rights Law. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 9781317169512.

- Rao, SK Ramachandra. Purusha Sukta – Its meaning, translation, transliteration and commentary.

- Griffith, R.T.H. (1899) The Texts of the White Yajurveda. Benares: E.J. Lazarus & Co., pp 260–262

- Griffith, R.T.H. (1917) The Hymns of the Atharva-Veda, Vol. II (2nd edn). Benares: E.J. Lazarus & Co., pp 262–265

- Purusha Sukta (in Sanskrit). Melkote: Sanskrit Sanshodhan Sansad. 2 October 2011.

- Raghwan (2009), Discovering the Rigveda A Bracing text for our Times, ISBN 978-8178357782, pp 77–88

- "Rgveda". gretil.sub.uni-goettingen.de. Retrieved 2018-10-29.

- The Purusha sukta in Daily Invocations by Swami Krishnananda

- Krishnananda, Swami. A Short History of Religious and Philosophic Thought in India. Divine Life Society, p. 19

- Aiyar, B.V. Kamesvara (1898). The Purusha Sukta. G.A. Natesan, Madras.

- Koller, The Indian Way 2006, p. 44.

- Koller, The Indian Way 2006, pp. 45–47.

- Haberman, David L. River of Love in an Age of Pollution: The Yamuna River of Northern India. University of California Press; 1 edition (September 10, 2006). P. 34. ISBN 0520247906.

- S. Radhakrishnan, Indian Philosophy, Vol. 1.

- Visvanathan, Cosmology and Critique 2011, p. 148.

- Nagarajan, V (1994). Origins of Hindu social system. South Asia Books. pp. 16, 121. ISBN 978-81-7192-017-4.

- J. Muir (1868), Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India – their religion and institutions at Google Books, 2nd Edition, pp 12

- Albert Friedrich Weber, Indische Studien, herausg. von at Google Books, Volume 10, pp 1–9 with footnotes (in German); For a translation, see page 14 of Original Sanskrit Texts at Google Books

- Colebrooke, Miscellaneous Essays Volume 1, WH Allen & Co, London, see footnote at page 309

- Müller (1859), A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature, Williams & Norgate, London, pp 570–571

- Jamison, Stephanie; et al. (2014). The Rigveda : The Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–58. ISBN 978-0-19-937018-4.

- Sources

- Koller, John M. (2006), The Indian Way: An Introduction to the Philosophies & Religions of India (2nd ed.), Pearson Education, ISBN 0131455788

- Visvanathan, Meera (2011), "Cosmology and Critique: Charting a History of the Purusha Sukta", in Roy, Kumkum (ed.), Insights and Interventions: Essays in Honour of Uma Chakravarti, Delhi: Primus Books, pp. 143–168, ISBN 978-93-80607-22-1

- Rosen, Steven (2006), Essential Hinduism, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0275990060

Further reading

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda, Rigveda 10.90.1: aty atiṣṭhad daśāṅgulám, Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 66, no. 2 (1946), 145-161.

- Deo, Shankarrao (Member of India's Constituent Assembly and co-author of the Constitution of India), Upanishadateel daha goshti OR Ten stories from the Upanishads, Continental Publication, Pune, India, (1988), 41–46.

- Swami Amritananda's translation of Sri Rudram and Purushasuktam,, Ramakrishna Mission, Chennai.

- Patrice Lajoye, "Puruṣa", Nouvelle Mythologie Comparée / New Comparative Mythologie, 1, 2013: http://nouvellemythologiecomparee.hautetfort.com/archive/2013/02/03/patrice-lajoye-purusha.html

- Purusha Sookta commentary by Dr. Bannanje Govindacharya.